Post-Soviet Suburbanization?

Dacha Settlements in Contemporary Russia

In the history of the modern dacha and its social catchment area there have been several important shifts: from the court society of the Peterhof Road to a more widely dispersed and more city-oriented aristocratic elite; from this aristocratic elite to the larger constituency of urban middling people; the emergence of a mass dacha market in the later nineteenth century; the sudden and drastic reclassification and reallocation of the dacha stock under the Soviets; the convergence of the dacha-plot dacha and the garden-plot dacha in the postwar era.

When we arrive at the 1990s it seems right to inquire whether another such shift might have taken place. In the West, most large industrialized urban centers have entered—perhaps even passed through—a stage beyond urbanization and industrialization: with the improvement of transport connections, the general rise in living standards, and the activization of the land market, many people—often, but by no means always, the more prosperous sections of the urban population—choose to relocate to areas safe from urban encroachment and establish new settlements, new values, and new lifestyles. In Russia this shift never quite happened, despite the attempts made in the late imperial period to establish exurban settlements with a new sense of community. The failure of such initiatives was grossly overdetermined: the harsh climate made problematic the extension of settlement to a low-density periphery; transport provision was inadequate and expensive; urban administration remained extremely centralized; the social unrest that intensified from the 1890s on made life in underpoliced exurban settlements unattractive. As regards the Soviet period, we can point to a whole new set of factors that inhibited suburban development—above all, the powerful resistance of Soviet planners to do anything that might be construed as emulating the West. Soviet policies placed great emphasis on urbanization and on maintaining a greenbelt around cities within the framework of a “unified system of settlement.” The intended result was that there should be a sharp urban/rural divide, not a grubby fade-out of city sprawl into countryside. The internal arrangement of Soviet cities also disposed them to patterns of settlement quite distinct from the Western suburbanization model. Urban functions were to be widely dispersed throughout the city space; cities were to be zoned so as to rationalize the deployment and use of infrastructure; social segregation was thereby to be minimized. These measures, combined with the total rejection of market principles in land pricing, ensured that there was at best a very shallow density gradient from city center to periphery. The urban population itself had no interest in moving out of the city. Given the concentration of resources in the major cities and the overwhelming importance of an urban residence permit in ensuring access to goods and services, it would have been foolish to contemplate such a move. In short, just as in prerevolutionary times, the metropolis lorded it over the surrounding region.

Even so, by the 1980s there were signs that Soviet cities were entering a suburban phase. The efforts of Soviet planners were to little avail, given the activities of their comrades in the executive. The priority given to greenbelt conservation in the i960 General Plan of Moscow came to seem little more than lip service, given the land-grab policies perpetrated in the 1970s and 1980s. In fact, it has convincingly been argued that the pressures on the swelling Moscow agglomeration in this period gave rise to a “socialist suburbanization” with three main distinguishing features.1 First, constant expansion of the city boundaries without any concomitant decentralization of administrative authority. Second, an expansion of Moscow’s outlying districts by large influxes of migrants from outside the urban agglomeration, not fueled by migration from the central districts of the city (as in the Anglo-American suburbanization of the postwar era). Third, the intensive development in Moscow’s hinterland of Soviet forms of garden and dacha settlement, which have no exact equivalent in the West.

The post-Soviet period has taken these processes a stage further, which raises a new set of questions. Given the liberalization of land policy in the 1990s, the Russian population’s acute concerns over subsistence, the continued overcrowding of the city, and the rise in the urban cost of living, have dacha and garden settlements fundamentally changed their character? Has suburbanization, with all it implies anthropologically as well as geographically,2 finally made significant inroads into Russia’s urban fabric?

Soviet Dachas in a Post-Soviet Context

By the 1970s, as we have seen, the word “dacha” covered a wide range of dwellings that varied greatly in function, appearance, and status. Four main types can be identified. First came the “departmental” dacha (kazennaia dacha), which was owned directly by a Party-state organization and was accessible only to those who occupied some position in that organization. Second was the Soviet-era “dacha-plot dacha,” almost invariably built under the auspices of an organization, and very commonly under the umbrella of a cooperative. Third was the modest dwelling built on a plot of land in one of the many garden cooperatives or associations set up since the war. Fourth was the privately owned dacha, which was either inherited or built at a time and in a place where land was available for such individual undertakings, or else bought ready-made (most commonly in a depopulated and underresourced rural area).

Although state-owned dachas varied enormously in their size and level of amenities, they still included a pool of spacious and well-equipped accommodations for government employees. In a Politburo discussion of July 1983, Iurii Andropov, the disciplinarian general secretary of the time, alleged that many of his colleagues in government were “overgrowing with dachas”: comrades in positions of responsibility were having spacious country retreats built for themselves, at the same time providing choice plots of land for their relatives. Speaking about the “leading workers in the Central Committee and government,” the up-and-coming Mikhail Gorbachev commented that “everyone is speculating with dachas, throughout the country. There are a whole lot of disgraceful phenomena in evidence.” He recommended that the Party control committee investigate such cases, but Andropov, although resistant to the bluster of other Politburo members, held back from this extreme measure.3 Figures that came to light a few years later, near the end of Gorbachev’s own period in high office, revealed the extent of official dacha holdings and the potential for abuse. In 1990 the Council of Ministers (the Soviet ministerial apparat) had at its disposal 1,014 dachas and two vacation complexes that in total comprised 55,000 square meters of living space; the annual subsidy was over 1 million rubles.4 At the end of its existence, in 1991, the Party’s Central Committee had dacha accommodations for 1,800 families in the Moscow region.5 The crusading newspaper Argumenty i fakty revealed in the same year that a group of “inspectors,” made up mostly of Soviet generals (numbering fifty-seven at the beginning of 1991) who had retired or been removed from their former posts, had a range of privileges—including access to the 142 dachas held by the Ministry of Defense—completely out of proportion to the scope of their present activities. Not only that, the “inspectors” had been actively abusing their privileges, in some cases unlawfully privatizing or selling off furniture held at state-owned dachas.6

Despite the populist campaign waged against elite privilege in 1990–91, the new political establishment in many cases simply took over the existing dacha accommodations. This was the case both at the apex of the political pyramid—Yeltsin and his changing cast of associates found themselves cozy retreats in Barvikha, Kuntsevo, and other resorts preferred by high Soviet cadres—and lower down. Statements of property and income made in January 1997 by administrators at the province (krai) level included spacious state-owned dachas of up to 600 square meters. Governor Evgenii Nazdratenko of the Far East, for example, with a (declared) annual income of $12,000, had a state-owned dacha of 257 square meters.7 Private dachas owned by government figures might attain truly palatial dimensions (as much as 1,000 square meters). These, we must assume, constituted former state property that officeholders had either appropriated or built with their dubious side earnings. For example, the chief of the Federal Treasury’s office in the same debt-ridden Far East province (Primorskii krai) was able to build himself a mansion outside Vladivostok that was valued at $645,000.8 The taking over of elite dachas by their occupants was quite common practice—although (or more likely because) it was not specifically covered by privatization legislation.9

Largely because of the lack of clarity and the ineffectiveness of property law, some former state-sponsored dacha settlements acquired a complex and disputed status in the 1990s. One example is the writers’ settlement at Peredelkino, run by the state-sponsored funding organization for literature, Litfond, from the late 1930s. On the collapse of the Soviet system, Litfond lost its subsidies and felt the pinch of market reforms. Legally, it did not even own the land on which the Peredelkino dachas stood. All it could do was rent out the existing accommodations. The central vacation home, the “House of Creativity,” accordingly became a modest hotel where rooms could be rented for as little as $10 a night. But even this sum fell outside the price range of most post-Soviet writers. Residents apprehensively discussed privatization of the dacha stock in the settlement as a whole, as private ownership was sure to change the character of the place irrevocably—to lead to the displacement of writers by newly moneyed families or representatives of the nonliterary elite. Peredelkino was among the most desirable locations for such people, as it combined ease of access to the city, excellent ecological conditions, and prestige. Even in the absence of a thoroughgoing privatization program, it had been infiltrated by the post-Soviet military and governmental establishment and by the despised nuvorishi. The most striking new mansion there belonged to Zurab Tsereteli, effectively the court architect of the Yeltsin regime. Good contacts in high places were sufficient to obtain permission to build new residences even in heritage zones such as this. Peredelkino’s vulnerability to the private building boom was accentuated by its uneasy administrative status: the settlement itself was located within municipal territory, but the adjoining lands were subject to oblast authority, and here new construction proceeded without adequate planning controls.10

The Garden Plot as a Mass Phenomenon

The story of former state-sponsored dacha settlements in the 1990s is revealing of post-Soviet networks of power and patronage, but it sheds little light on the dacha’s broader social significance. This significance, as we have seen, increased enormously with the postwar growth in cultivation of allotments and garden plots, and the years of Gorbachev’s reforms brought a further giant step forward. A joint Soviet Party-government resolution of 7 March 1985 pledged support to the garden-plot movement. The immediate response of the RSFSR government was to formulate a program for boosting infrastructure in garden associations with a view to providing between 1.7 and 1.8 million new plots between 1986 and 2000.11 In 1986, a recommended form for the statutes of such an association was approved. Traditional Soviet restrictions were still very much in force: buildings on garden plots were to be mere “summer garden huts” (letnie sadovye domiki) with a total living space of no more than 25 square meters; outbuildings (including huts for rabbits and poultry, sheds for gardening equipment, and outdoor toilets and showers) were to total no more than 15 square meters; the overall area of a plot was to fall between 400 and 600 square meters.12 The RSFSR program for garden-plot development was by this time much more ambitious than the previous year’s: now the plan was to increase the number of plots by more than 700,000 a year over the next five years and to improve the supply of building materials and the provision of services in garden settlements.13 And in 1988 even the approved statutes were more relaxed: now garden houses could be heated, the area of land under construction could be 50 square meters (not even including terraces and verandas), and there was no stated limit on the area for outbuildings.14 A 1989 resolution promised to set up trading centers in garden settlements where dachniki could sell their produce and buy building materials and equipment.15 All the while, the Moscow ispolkom was pledging to accelerate the creation of new settlements by searching out suitable land and taking less time over the necessary paperwork.16 By 1987, more than 4.7 million citizens of the Russian Federation had “second homes” on garden plots (as compared to a mere 55,000 with dachas proper).17

The momentum accelerated in 1989 and 1990, when plots of land were easier to obtain than ever before. In January 1991, moreover, Gorbachev issued a decree on land reform that argued the need to conduct an inventory of agricultural territories and reallocate the land that was used inefficiently to peasant households, agricultural cooperatives, personal holdings, and dacha construction.18 Research based on data collected in 1997 in four widely scattered urban locations (Samara, Kemerovo, Liubertsy, Syktyvkar) suggested that the median amount of time a household had been using the dacha was in the region of ten years. In other words, the dacha qua garden plot had historical roots (in the houses that people owned or inherited in the Brezhnev period) but still received a significant boost in the late 1980s and early 1990s.19

The Soviet government’s encouragement of smallholding and garden-plot cultivation had an explicit rationale: to boost production of basic foodstuffs in the face of an impending supply crisis. Annual yields from individual plots were monitored and received comment in central government resolutions.20 And problems, notably the reluctance of local soviets to allocate land for individual agriculture, were anxiously noted.21

The Moscow city administration, for example, was in 1990–91 keen to hand out less agriculturally productive land to garden cultivators, arguing that to do so would lessen the food crisis and reduce the pressure on housing in the capital. An RSFSR resolution of February 1991 noted that the supply situation in Moscow had deteriorated and set the target of providing not less than 300 square meters for each Moscow family in that year’s growing season (the land was to come from collective farms and to be concentrated along the main railway lines).22 The initiatives of the late 1980s had brought only partial success, given the red tape involved in the allocation of land.23 Near the major cities, where demand for land was at its most intense, there had developed “a battle for land between citizens desiring to obtain plots and the often reluctant local authorities, wishing to preserve the land for agriculture and other purposes.”24 At the beginning of 1991, more than one million people in Moscow were estimated to be on the waiting list for a plot of land. The oblast authorities, claimed the city administration, were frustrating the garden-plot initiative by agreeing to allocate only highly unproductive land belonging to state farms. Building materials were as difficult as ever to obtain; it was argued that construction needed to be reoriented from high-rises to small single-family homes. Land, however, was to remain cheap:

Why should people have to buy [plots of land]? I believe that people should receive land free of charge: if they love the land and are able to cultivate it, let them work away and take as much as they can cope with. Not 100 square meters but 1,200 or 1,500, or even 2,000 if someone wants to have a minifarm on their plot with poultry and livestock. On the same plot they can build their family a house with a cellar, a garage, and various outbuildings. There isn’t room for a family on 600 square meters.25

Although the speaker here—then president of the Moscow soviet—is presenting himself as a passionate advocate of progressive land reform, he uses a very traditional argument: economic value is less significant than use value. Research suggests that this attitude was shared by people who were unimpressed by receiving as private property land that they considered theirs anyway.26 That said, the new land legislation did advance the cause of Russian private ownership: right to use (pravo pol’zovaniia) was firmly replaced by lifelong ownership with right of inheritance (pozhiznennoe nasleduemoe vladenie).27 And the concerns of the city administration were addressed in one of the first presidential decrees of post-Soviet Russia, which set the target of 40,000 hectares to be provided for construction of individual houses in the Moscow region in the next ten years.28

Millions of Soviet people, in Moscow and dozens of other cities, seized the opportunity to begin life as a garden-plot cultivator (sadovod). Here again, use of the land, not ownership, was the primary concern. As economic reform stumbled, Soviet citizens began to lose faith in the states ability to feed them, and so invested more time and energy in the productive function of their dachas. If garden cooperatives in the 1970s had tended to have a rather horticultural feel, by the late 1980s their inhabitants were taking a subsistence-oriented approach to cultivation of their land.29 In the 1980s and 1990s the term “dacha” underwent further expansion so as to connote the two very different functions—leisure and subsistence—that a plot of land in post-Soviet Russia might serve. In other words, the dacha continued to converge with the garden plot in people’s understanding; it was, in the words of one self-help book, a “minifarm.”30

Muscovites’ colonization of their oblast was remarkable. By 1995, garden associations numbered more than 7,000 in the region (the total number of plots was 1.5 million). And the average size of a holding had grown significantly, as the area of a new plot was often 1,000 square meters rather than the 600 that had been standard in Soviet times. In thirty-four of the thirty-nine districts (uezdy) the number of sadovody exceeded that of the local rural population. The “old” dachas were privatized (often with a reduction in the size of adjoining plots of land). The total number of urban families with some sort of second home in the Moscow oblast was around 1.65 million (75 percent were Muscovites; the rest were from smaller towns in the oblast).31 In St. Petersburg, it was estimated in 1997 that between 60 and 80 percent of families had some kind of landholding; the time spent there ranged from twenty-seven days annually to virtually the whole of the owners’ spare time.32 In Leningrad oblast in 1999, 2.5 million people went to the dacha every weekend; 500,000 lived at the dacha all through the summer.33 A 1993–94 survey conducted in seven Russian cities found that 24 percent of households owned a dacha (the proportion with some form of landholding would have been much greater). The garden-plot dacha was comfortably the most prevalent variety, forming just over half of the overall dacha population.34 The rural house, by contrast, had suffered a decline in popularity, as people aspired to build their own houses, both better equipped and more conveniently located.35 Overall, the number of owners of plots in the Russian Federation rose from 8.5 million at the start of land reform in 1991 to 15.1 million in 1997.36 In 1999 came the ultimate recognition of the centrality of the garden-plot dacha to the nation’s experience: a public holiday—Gardener’s Day (den’ sadovoda)—was instituted in its honor.37

Subsistence-oriented dacha life expanded most rapidly in the Moscow and Petersburg regions, but it was by no means limited to them. Towns and medium-sized cities had never had much need of the dacha concept or the out-of-town leisure it entailed. Most families had at least a small plot of land within easy reach of their apartment. But now even such modest plots were often reclassified as “dachas.”38 There was some regional variation in vocabulary: in the Urals, for example, a garden plot (with or without a house) tended to be called a sad (garden), while in the northwestern region of Russia it was likely to be referred to as a “dacha.”39 The word “dacha” seems to have made relatively few inroads into the Black Earth region and the south of Russia, where the urban populations ties to the land were rooted firmly in an alternative tradition. In the provincial city of Lipetsk, some 500 kilometers south of Moscow, local people commonly spoke of making trips not “to the dacha” (na dachu) but “to the garden” (na sad, instead of the neutral v sad), which suggests that they conceived of their plot of land neither as a dacha proper nor as a garden plot but as an independent agricultural landholding.

Post-Soviet Dachniki: Social Profile, Attitudes, Ways of Life

Although garden-plot cultivation in contemporary Russia is often viewed as a survival strategy, it is not generally practiced by the poorest families. Post-Soviet dachniki are drawn mainly from the thick middle strata of urban society. Large families with adequate material resources are the most likely to grow their own produce, even if their adult members are in paid employment. As Simon Clarke writes: “Like secondary employment, it seems that rather than being the last resort of those on the brink of starvation, domestic agricultural production provides an additional form of security for those who are already quite well placed to weather the storm.”40 This general observation can be supplemented by certain minor correlations. A household is much more likely to cultivate a garden plot if at least one member has grown up in a rural area or if its head is married. The age of the household head is also significant, thirty to sixty being the peak range for gardening activity. And male-headed households are less likely than female-headed households to grow all or most of their own vegetables. This finding matches abundant anecdotal evidence that women tend to take charge of managing the dacha landholding.41

So, as Clarke points out, the question why people produce ought to be rephrased as why people acquire land in the first place. And here again there is a strong correlation with earnings and occupational status. On the whole, it was families with a reasonable level of material security that took up the state’s offer of a garden plot in the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s; the cultivation and upkeep of a plot (not to mention the construction of a house) implied considerable expenditure and little, if any, income. Dacha produce was not usually sold: only 1 percent of all households had any net positive monetary income from subsidiary agriculture. Vegetables surplus to the household’s requirements were commonly distributed among friends and relatives at the end of the dacha season. The food bills of families with a dacha were no lower than those of people without a plot of land.

Subsistence, then, usually cited as the prime motivation behind the dacha boom of the 1990s, is only part of the story. It is worth noting that the powerful garden-plot movement, mostly seen as a pragmatic response to severe food shortages, coincided with a broader deurbanizing trend. Ever since 1927 the Soviet Union had been increasing its level of urbanization; and in the period 1979–88 there had been a distinct leveling up as the less urbanized regions caught up with the others. In 1989–90, however, urban development slowed, and in 1991–94 it actually went into reverse. This trend was particularly marked in the southern agricultural regions, but it also touched major cities in central Russia. Net migration between the city of Moscow and the surrounding oblast by 1994 favored the oblast. The major cities were in this sense becoming provincialized.42 It seems that a significant part of this out-migration was due to rising rents in the city. Trapped in tiny apartments and unable to afford better ones, many Muscovites chose to make their dachas their primary residences.

The Moscow region had been subject to creeping suburbanization (or proto-suburbanization) for several decades. The sheer volume of commuter traffic into the city from the surrounding oblast was telling: 600,000 people a day by the early 1990s.43 In 1979, 120,000 people lived in the most remote peripheral areas of Moscow (beyond the Outer Ring Road); by 1995 that figure had risen to 500,000. In theory, of course, suburbanization was something that Soviet planning was designed to avoid: the Soviet model of the city aimed for a far more even spread of population and function than its Western counterpart.44 A greenbelt was to be preserved around the city, and satellite settlements were to be built beyond this forest zone. In the case of Moscow and several other major Soviet cities, however, this model did not shape reality. Although lip service was paid to keeping distinct the urban-rural boundary around Moscow, in practice this policy was not observed.45

In the mid-1990s the suburbanization of Moscow began to conform a little more closely to the Western model. Very little effort had been made in the first half of the decade to keep the greenbelt intact; even unspoiled park areas in the city’s closer environs had been given over by feckless or corrupt bureaucrats to development as garden or dacha settlements.46 In addition, the ever-expanding agglomeration seemed to be changing its character somewhat. For the first time ever, significant numbers of Muscovites started to exchange their centrally located apartments for small houses on the outskirts of the city. And even those who stayed put for the time being were more ready to contemplate such a move. The ambiguous status of many contemporary dacha settlements was confirmed by a survey conducted in the summer of 1997, which found that 40 percent of respondents regarded the dacha as “true country life,” 55 percent as “suburb” (prigorod), and 5 percent as a no-man’s-land.47

Housing construction in the private sector was encouraged by a presidential decree of 1992, and in 1993 the Moscow city administration announced a plan for the development of the suburban zone.48 Boris Yeltsin’s decree on land reform of October 1993 established a basis for a rudimentary land market. Restrictions and gray areas remained—it was specified, for example, that land use was not allowed to change after a transaction unless “special circumstances” obtained—but they affected the dacha market relatively little. Local authorities were concerned principally to prevent the sale of large chunks of agricultural land for nonagricultural purposes; small-scale transactions involving allotments and garden plots were unlikely to fall foul of the regulations (although they might still be bureaucratically complicated, especially where land hitherto owned “collectively”—notably in cooperatives—was at issue).49 Comparative analysis of the housing market in 1994 and 1996 revealed a great increase in the number of advertisements, a slight fall in prices, and a much greater differentiation of prices according to location and distance from Moscow (the most expensive regions were to the west of Moscow, in the directions of Minsk and Kiev). On the eve of the ruble’s devaluation in the summer of 1998, monthly rents in the Moscow region ranged from two hundred to several thousand dollars.50 But newspaper advertisements were only part of the story: in time-honored fashion, rental tended to be arranged by personal acquaintance or through fixers; real estate agents were reluctant to involve themselves in the short-term dacha market.51

Alongside traditional summer-only dachas there appeared a new type of year-round out-of-town house that was often called a kottedzh to emphasize its Western pedigree. The size and degree of comfort of such dwellings varied enormously. Many of them, contrary to general perceptions, were extremely modest, lacking such basic amenities as electricity and standing on the same 600-square-meter plots that held the dachas built by individual families in the 1950s and 1960s. They differed only in that they were normally made of brick rather than wood, had two stories, and had slightly more room inside (the average size of a winterized dacha, according to the fullest survey of the mid-1990s, was 44.6 square meters, as opposed to just over 30 square meters for summer-only constructions).52 At the other end of the market were the “New Russian” mansions beloved of glossy magazines. Many of these houses were hidden behind lofty fences in locations favored by the Soviet elite; but the more elaborate of them might also stand, incongruously, in old settlements alongside wooden shacks rather than in new ghettos for the superrich. Various attempts have been made to account for the apparent indifference to visible disparities of this kind: some say the owners of spacious villas want to display their wealth as publicly as possible; others assert that their choice of location is dictated by the impossibility of obtaining planning permission to build elsewhere. The second explanation is, to my mind, improbable: inasmuch as many New Russian houses in preexisting settlements themselves infringe multiple planning regulations, it appears that buying off the regional authorities is not so very difficult. Perhaps the reason is simply that New Russians are in a desperate hurry to convert their wealth into immovable property.

This incursion of new money certainly changed the atmosphere of many settlements. It had the effect of quickly redistributing land, as long-standing residents of prestigious settlements such as Peredelkino found new neighbors in unwelcome proximity. Often the new houses were built on formerly sacrosanct wooded land or green fields that had been signed away at a stroke of the bureaucrat’s pen, but in some cases large Soviet-era plots were subdivided and portions sold off by owners impoverished by the collapse of the old regime and devoid of any better source of income. The arrival of New Russian kottedzhi also brought a reassertion of the dacha’s leisure and ornamental functions. Gardening firms, for example, noted an increase in orders for junipers and cypresses, plants that were hardly suited to the harsh Russian climate but were nonetheless symbolic of a new lifestyle.53

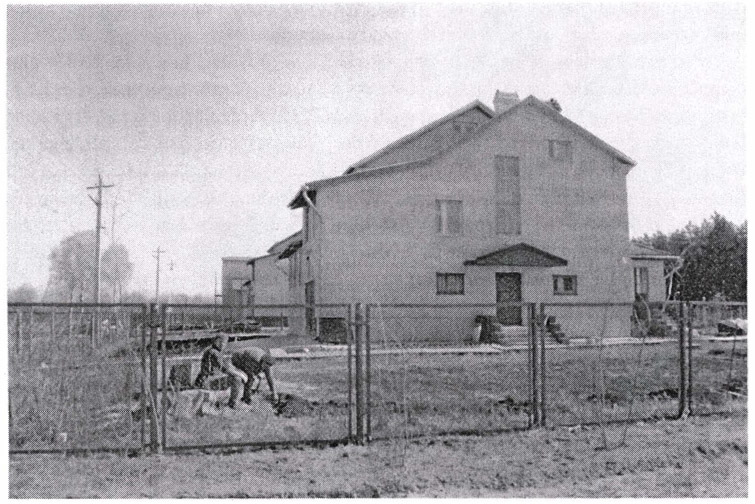

A New Russian dacha at Mozhaiskoe, southwest of St. Petersburg. The architectural pretensions of this house are undermined by its grubby surroundings. This is hardly a scenic spot, nor is it secluded: the dacha stands in full view of the local train stop.

Most dachas, however, fell between the extremes of solid, centrally heated kottedzh and 1960s garden shack. In the Moscow and Petersburg regions in the mid-1990s just over half of dacha owners had built their country houses on their own or with a small amount of help from hired workers. And the proportion of do-it-yourself dacha builders in smaller cities was even greater (in Moscow and Petersburg the inheritance figures were substantially higher).54 Building work, as in the Soviet period, was generally extremely time-consuming and physically demanding; it often involved felling timber and slowly and painfully extracting tree stumps from the marshy or wooded land that was allotted to the new settlements. When family resources permitted, owners would try to profit from the relaxation of Soviet-era restrictions to build themselves a slightly more spacious house.55 But many people who did not have time to build their dacha in the last years of the Soviet era found that after price liberalization they simply could not afford to do so. For aspiring dacha owners in the 1990s, timing was crucial: the people most advantaged were those who had time to take out loans and lay in supplies of building materials before January 1992. For those who were unable to take such action, dacha construction often became a long and frustrating slog. Even a very simple dwelling might take ten or fifteen years to complete. Some partially built houses were simply abandoned, their owners having lost all hope of finishing the job: in a reference to the economic crisis and currency devaluation of late summer 1998, these were commonly known as “August [1998] dachas.”56

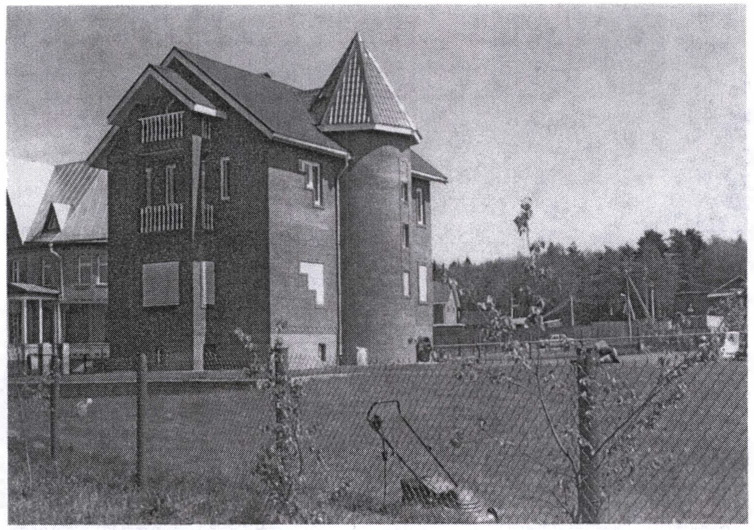

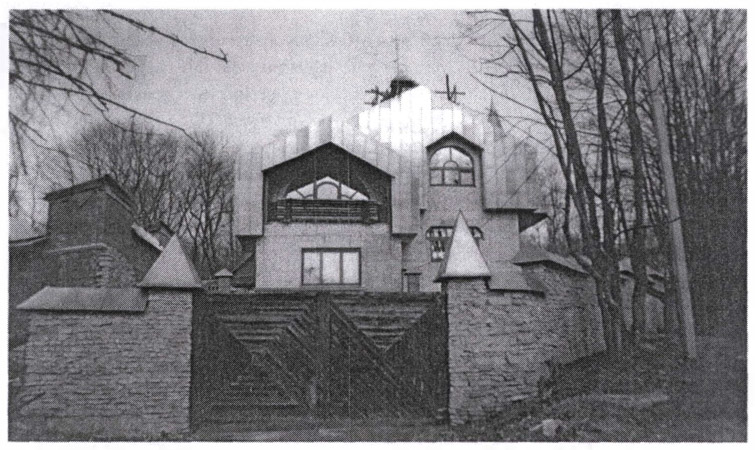

A house near the Zelenogradskaia stop on the Moscow-Iaroslavl’ line, between Pushkino and Abramtsevo. Although this dacha is located in a garden settlement, its large and well-maintained lawn bespeaks a rejection of the Soviet agricultural imperative and a turn toward Anglo-American civilization. Only the turret betrays the owner’s Russianness.

A dacha at Mozhaiskoe. Contemporary dachniki frequently invoke the English saying “My home is my castle.”

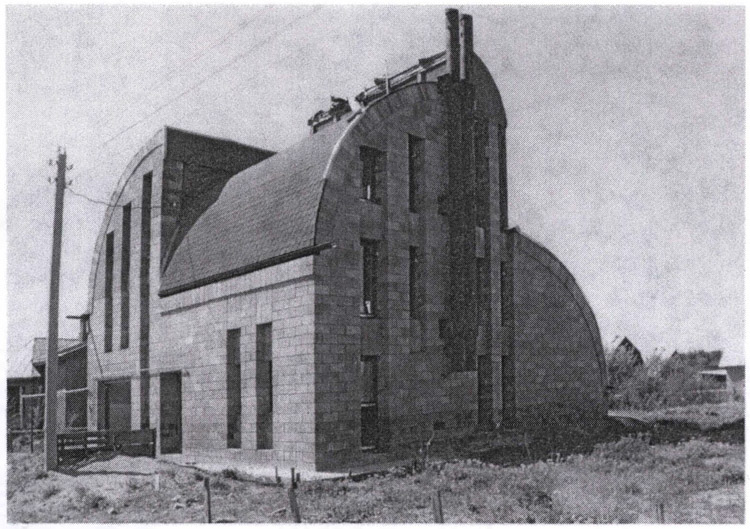

Locals dubbed this dacha at Zelenogradskaia “the crematorium.”

Post-Soviet dachas had a rather basic level of home comforts. Research carried out in the mid-1990s suggested that just over half of dachas were equipped with gas—generally a ring with a cylinder—but only 5 percent had plumbing.57 The average floor area of a garden-plot dacha was a modest 29 square meters.58 Nor was the level of amenities in the settlement as a whole any better—especially given the size of settlements, which might reach that of a small regional center. For the 200,000 people crammed into Mshinskaia (110 kilometers from St. Petersburg) there were only ten policemen and one first aid brigade, and the nearest shop was 4 kilometers away. The result of the population compression that had taken place over the last fifteen years was, in the assessment of one journalist, an enormous open-air communal apartment.59

Distances, too, had grown enormously. In the 1960s, the dacha belt rarely extended more than 60 kilometers from the city; in the 1990s, however, families commonly went to the very end of a suburban rail line (around 120 kilometers). And areas for settlement were not often within easy reach of the railway: they might easily be as much as forty minutes’ walk away. The rise in car ownership has also done much to enable city dwellers to colonize broad territories between the radial railway lines. In 1993–94, 50 percent of people in the Moscow region were commuting 75 kilometers or more to the dacha, which represented no small investment of time, especially if buses and suburban trains were the only available means of transport. Distances in the Petersburg region were somewhat shorter, in provincial cities shorter still.

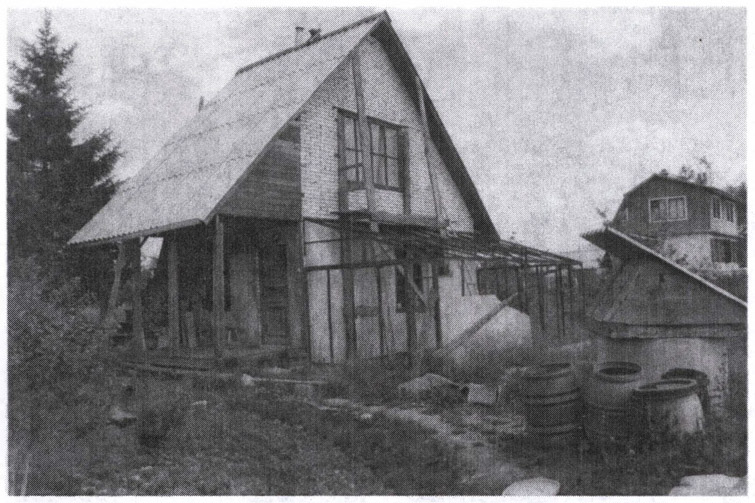

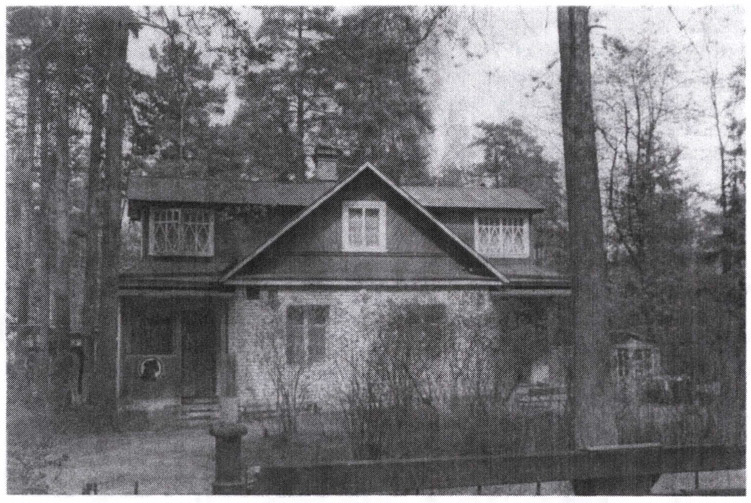

A post-Soviet garden-plot house at Krasnitsy. In June 1999, when this picture was taken, the house had been under construction for ten years.

This dacha at Mel’nichii Ruchei is a not untypical post-Soviet architectural hodgepodge; the “Beware of the dog” sign is a further reminder of contemporary realities.

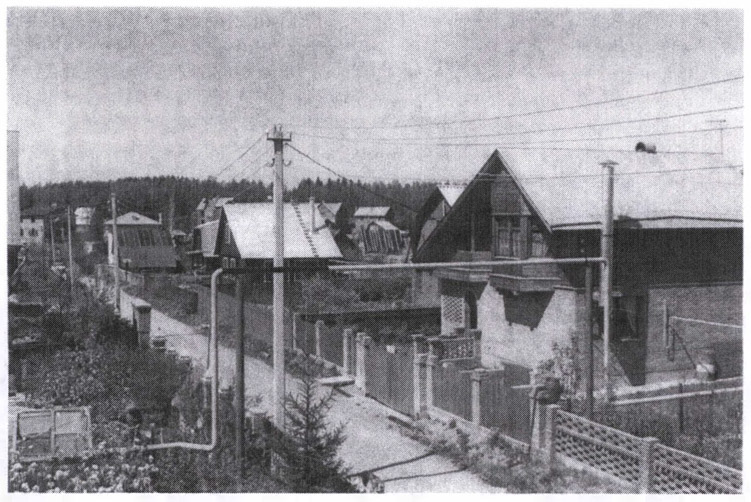

This garden settlement (Zelenogradskaia) was established as a garden cooperative in 1987, though dacha construction did not get under way until two or three years later. Although members of the cooperative were given equal shares of land, ten years of mainly post-Soviet life have brought striking variation in the ways people use their plots.

The liberal land policy of 1990–92 had the great virtue of giving millions of Soviet citizens a plot of their own, but it also illustrated the problems associated with liberal property legislation in the absence of adequate means of enforcing property rights. Disputes between neighbors were frequently provoked by the unlawful seizure of land by one party.60 Since 1991 exurbanites have been plagued by burglars, just like earlier dachniki. A newspaper feature in 1992 told of residents who had taken the law into their own hands after discovering thieves on their land. While admitting that turning a rifle on someone for stealing a few cucumbers might be excessive, the article argued that such cases would continue to be common until state law enforcement was more adequate.61 In 1999, people with long memories of dacha life were asserting that such a crime wave had not been seen since the hungry year of 1948. Thieves would take anything, from televisions to bed linen, doors, and window surrounds; metal items were a particular favorite, as they could be handed in for money at recycling points.62

A further problem concerned not the enforcement of the right to property but the nature of this right. In December 1992 a federal law on housing specifically indicated that houses built on dacha and garden plots were to be covered by privatization legislation, but until new legislation in 1997 the procedure involved was not regularized, so that local authorities were free to impose their own bureaucratic procedures (with corresponding charges).63 The law on ownership was appallingly cumbersome; often it was impossible for people to sell a small plot without actually taking a loss on the transaction. And the legal distinctions between the various forms of gardening association—association (tovarishchestvo) cooperative, society (obshchestvo)—were not at all clear.64 One woman observed:

Our cooperative fell apart, of course, and it was only after it was gone that we understood that in some ways it had made life simpler. For example, passing on a dacha used to be a formality: all you had to do was write a letter to the administration: “I request that my share [pai] be transferred to my son/niece/aunt.” The meeting voted unanimously in favor and the aunt became a member of the cooperative—in other words, a dacha owner in disguise. Now you have to pay enormous inheritance taxes and people say it’s better to sell the dacha to your auntie—that way apparently the taxes are lower. It’s not clear who is supposed to repair the roads now—and there’s a pile of other little things that the cooperative administration used to deal with.

The government, for all that it had been quick (especially on the eve of elections) to promise special measures in support of garden associations,65 had been slow to make the necessary infrastructural provisions, to reduce the tax burden on growers, and to provide a stable legal framework for ownership.66

In short, Russia had a long way to go before it could create in dacha settlements the ”moral order” of the suburb identified by one urban anthropologist.67 “Moral minimalism”—that is, the avoidance of conflict and a reluctance to exercise social control against one’s neighbors—may be the foundation of the order that prevails in many of the suburbs now inhabited by more than half of the U.S. population, but Russian dacha communities function rather differently. The American developments are characterized by fluid social relations (not least because of the much greater social and geographical mobility of their residents) and low levels of social integration.

Although Russians did not have the luxury of social indifference and the corresponding strategies of conflict avoidance, it could hardly be said that post-Soviet dacha settlements lacked a moral order of any kind. Geographical mobility was much more limited than in the United States, and for this reason Russians were drawn into long-term close-quarters relations with their dacha neighbors. Russians were denied the privacy afforded by the suburban crabgrass frontier; building and maintaining a dacha was, on the contrary, a very public (and generally prolonged) affair that drew people willy-nilly into new social networks. The result was that Soviet traditions of mutual aid in defiance of public administration and systems of distribution—the proverbial blat—lived on, even under newly monetarized post-Soviet conditions.

Similarly, a number of Soviet/Russian social identities persisted in adapted or attenuated form. The dacha (read: garden plot) explosion became truly a movement, with its own public profile, set of values, and subcultures; besides numerous publications, it had its own TV program, titled 600 Square Meters. Physical toil was the moral centerpiece of all this publicity. The emphasis was placed on “healthy peasant physical labor,” on the virtues of “cultivating one’s own garden” and thereby achieving a self-sufficiency rooted in the soil and invulnerable to political or social upheaval.68 One of my informants expressed a complementary but much less sympathetic view by as she reflected on the Russians’ apparent magnetic attraction to the soil in the late Soviet and post-Soviet periods:

Of course people are drawn to the soil. Of course there is something of a hobby and something of an adventure about it. But. . . ?! The best answer to this question I heard from my father-in-law. He made out that everyone wants to show their neighbors how well they can work. In other words, it’s “Labor is a matter of honor, glory, valor, and heroism” all over again. But [you might think that] at the factory there is ample opportunity for this kind of activity! And everyone sees how everyone else works. But it turns out that this is something quite different. No one envies someone who fulfills or overfiilfills the production plan. But a good harvest of cherries, for example, can make your neighbor burst with envy. It’s not even material envy, but [a sense of] their own imperfection.

Whatever role we ascribe to Soviet conditioning in the behavior of contemporary dachniki, they certainly seem to derive a positive self-image from purposeful and productive cultivation of their garden plots. In Russians’ pronouncements on their dachas one can often sense an undercurrent of national identification, a worldview expressed approximately by the phrase “We may be poor, but. . .”69 The dacha is presented as something quintessentially Russian, less luxurious and spacious than the vacation homes of Americans or Western Europeans but more authentically rural and representative of Russians’ inborn bond with the soil and appetite for hard physical work. At the same time, the dacha is conceived of as meeting a universal human impulse to flee the city and work the land. Here the West may figure in people’s discourse as supporting comparative material:

Let’s take a look at a country like England that is conservative, traditional, but conservative in the good sense. And what do we see? What did all political figures dream of, take Churchill, take who you like. What did they dream of doing when they got to have a rest, I mean when they retired? And what about our beloved Sherlock Holmes, what did he end up doing at the end of his life? They all dreamed of one and the same thing: to grow roses on their own plot of land.70

The dacha thus offers the opportunity for rest as opposed to mere lounging about (rasslabukha) or, more precisely, for “active leisure” (aktivnyi otdykh): judging by the frequency of its occurrence in my interviews, this term, born of the Soviet sociology of leisure, seems to have put down roots in the collective mentality.

But going to the dacha is also regarded as a pleasurable activity, largely because of the lack of alternative forms of entertainment: “What is there to do at home here? Sit in front of the TV, I suppose? There people chat with one another in the evening, they’ll get together in the house, maybe have a barbecue, they’ll have a drink before supper, then they have a chat.”71 Life out of town gives rise to forms of sociability that often blur into mutual aid and support. Russians on their garden plots affirm the importance of “friendship” as they would in their apartments, but here they do so with an anti-urban emphasis: members of dacha communities see themselves as more people-centered, more in touch with their feelings, and better able to enjoy themselves than pampered city folk. Favors are simpler and delivered more immediately than in urban blat relationships. Networks are less circular, in the sense that people may return a favor directly to the person who has done one for them (for example, in the exchange of surplus produce at the end of the dacha season). But perhaps more important than actual services rendered and received is the broader sense of a community united by common interests: advice on seedlings shared with strangers on the train ride back to the city fosters a belief in the garden plot as the main experience that post-Soviet citizens hold in common.

Although Russians’ feeling of belonging (for better or worse) to a large garden-plot community is strong, just as striking is the satisfaction they gain from their own landholding. As Nancy Ries comments, although subsistence gardening is a grind, “the pride with which people displayed their gardens, their colorful anthropomorphizing of the fruits of their labors, and their dedication to this lifestyle signaled the symbolic value and identity they derived from these practices.”72 Pride is also attached to the dacha residence itself and to the domestic environment associated with it. Despite restrictions on design, Soviet citizens were able to exercise far more choice in the internal arrangement of their dachas than in the layout of their urban apartments. Apartments were the outcome of a protracted and impersonal allocation process, while dachas were the result of one’s own labors. Unsurprisingly, Soviet people were far more positively disposed toward their dachas—which in many cases they or their parents had built themselves—than toward their apartments. Dachas, in short, were the closest many Soviet citizens came to a private home, and brought a genuine improvement in their quality of life.73

But, although the contemporary Russian garden settlement richly deserves further anthropological investigation as an important, apparently antimodern alternative civilization, it should perhaps occasion not cultural celebration but profound regret as a symbol of the poverty and powerlessness of the bulk of Russia’s population even in the relatively prosperous major cities. In the words of Simon Clarke: “The dacha makes no economic sense at all, providing the most meagre of returns for an enormous amount of toil, but it is much more than a means of supplementing the family diet or of saving a few rubles. It is both a real and a symbolic source of security in a world in which nothing beyond one’s immediate grasp is secure.”74

BACK IN 1991, Gavriil Popov had seen the garden plot as a means of achieving suburbanization. He anticipated that people would sell their apartments in the city once they had built their houses (a land bank would be able to advance them up to 60 percent of the price of their apartment while construction of the new house was in progress). In a further optimistic prognosis, he saw Russia emulating America’s suburbanization:

the country will be in transition from a state reminiscent of America in 1929 or 1930 to that of America in the postwar era, when a house in the suburbs became the basic modern form of life for a person working in the city. As a matter of fact, this is precisely what the forgotten classics of Marxism-Leninism were thinking of when they reckoned on the fusion of the city and the countryside. What we ended up with was not fusion but extreme separation.75

In this settlement near Pavlovo, Leningrad oblast, can be seen some of the anomalies of the contemporary dacha. The attire and demeanor of the owners of this plot might seem to mark them out as typical ex-Soviet garden toilers, yet their house is immeasurably grander than anything conceivable in a Soviet garden settlement. (The size of the house turns out to have a simple explanation: the settlement was established under the auspices of a local brick factory, so good-quality building materials were both plentiful and cheap.) By the time this picture was taken (April 1999), the social composition of the settlement had diversified greatly since the early days, when all plots had been distributed to members of the factory’s workforce. Several of the original recipients had lacked the resources to finish building their houses, and so had sold their plots to New Russians. But the couple in the foreground had avoided such material difficulties and insisted that they would maintain this house as their dacha, though it would clearly serve very well as a permanent dwelling.

But, as we have seen, these “garden settlements” had very little in common with leafy suburbia in an American understanding. Far from liberating the Russian people from the yoke of socialism by fostering the values of individual initiative, civic association, and private property, the mass dacha of the 1990s may be seen to have had the opposite effect—of reinstituting reliance on cash-free mutual aid and primitive forms of subsistence farming. In support of this view we can cite an opinion just as forthright as Popov’s—that of Eduard Limonov, the eternal enfant terrible of contemporary Russian literature:

The dacha turns a Russian into an idiot, it takes away his strength, makes him impotent. Any connection with property tends to make people submissive, cowardly, dense, and greedy. And when millions of Russian people are attached to dacha plots and spend their time planting carrots, potatoes, onions, and so on, we can’t expect any changes in society.76

How are we to square two such radically opposed views? It is hard to disagree with Limonov that the survival strategies that millions of Russians are forced to adopt place severe limits on their political and economic activism. Yet, although Popov’s assessment seems far too sanguine, it does identify a widely felt householder impulse that Limonov, with his intransigent hostility to property, cannot appreciate.

Even so, it does seem possible to pull these two dacha pundits together and generate a number of paradoxical hybrid descriptions. Thus contemporary dacha settlements may be seen as a symptom of the provincialization of city life: in a reversal of modernizing trends, the inhabitants of major industrial centers are opting for the smallholding way of life that has for centuries prevailed in the Russian small town. Or alternatively, the dacha boom can be taken as evidence of the peasantization of Russia’s “middle class” (a thick stratum of society defined merely by the fact that it is likely neither to starve nor, by the standards that prevail west of Brest, to achieve a remotely acceptable level of prosperity). And finally, dacha sprawl is, to coin a phrase, a form of shanty exurbanization. That is to say, it is driven both by the urge to flee the expanding city and set up an independent community in a rural setting (the exurbanizing impulse) and by the imperative to provide for one’s basic needs in the absence of adequate legal protection and infrastructural provision (the shanty predicament).

The truth, however, is that no single description will capture the diversity of forms of settlement and habitation that go under the name of “dacha” in post-Soviet Russia; nor will it adequately encompass the range of motivations that propel dachniki out of town each summer weekend; nor, finally, can it serve as an accurate guide to the future. All of which suggests that the dacha will remain culturally as well as horticulturally productive for a while yet.

1. The idea of “socialist suburbanization” is borrowed from Iu. Simagin, “Ekonomiko-geograficheskie as-pekty suburbanizatsii v moskovskom stolichnom regione” (dissertation, Moscow, 1997).

2. “Suburbs” is a difficult term with different shades of meaning even in countries so apparently culturally congruent as Canada, Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. One cogent explication lists five main aspects of the concept (which may, however, be weighted rather differently from one country or city to another): (1) peripheral location in relation to a dominant urban center; (2) partly or wholly residential character; (3) low density; (4) distinctive culture or way of life; (5) separate community identity, often embodied in local government. See R. Harris and P. J. Larkham, “Suburban Foundation, Form, and Function,” in Changing Suburbs: Foundation, Form and Function, ed. Harris and Larkham (New York, 1999), 8–14.

3. Thanks to Jana Howlett for the transcript of this discussion.

4. See Sh. Muladzhanov, “Pomest’e po-ministerski,” Moskovskaia pravda, 2 July 1991, 3.

5. S. Taranov, “Sobstvennost’ KPSS: Koe-chto iasno, no daleko ne vse,” Izvestiia, 27 Aug, 1991, 1.

6. A. Kravtsov, “‘Chtob ia tak zhil!’” Argumenty i fakty, no. 35 (1991), 6.

7. Full details in “Bigwigs’ holdings,” at <http://vlad.tribnet.com/1997/iss153/text/table.htm>.

8. See “Outrage as deluxe dachas rise from rubble,” at <http://vlad.tribnet.com/1998/iss171/text/news10.html>

9. Early examples from journalism include Muladzhanov, “Pomest’e po-ministerski,” and E. Berezneva, “Kto, gde, kogda i pochem privatiziroval gosdachi,” Kuranty, 7 June 1991, 1. There is an intelligent discussion of this issue in T. Colton, Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis (Cambridge, Mass.), 713–14.

10. On recent developments in Peredelkino, see N. Emel’ianova, “Nepriiatel’ v Peredelkine,” Vechernii klub, 25 Sept. 1999, and Robin Buss, “Letter from Peredelkino,” TLS, 24 Sept. 1999, 14.

11. “O merakh po razvitiiu uslug po remontu i stroitel’stvu zhilishch, postroek dlia sadovodcheskikh tovarishchestv, garazhei i drugikh stroenii po zakazam naseleniia v 1986–1990 godakh i v period do 2000 goda” (21 May 1985), text in SPP RSFSR, no. 15 (1985), art. 71. The late 1980s were also a time when the Party finally gave its unqualified approval to the “personal subsidiary farm” (lichnoe podsobnoe khoziaistvo) that had for so long endured an equivocal and shifting legal status: see V. Ustiukova, Lichnoe podsobnoe khoziaistvo: Pravovoi rezhim imushchestva (Moscow, 1990), esp. 7–16, and Z. Kalugina, Lichnoe podsobnoe khoziaistvo v SSSR: Sotsial’nye reguliatory i rezul’taty razvitiia (Novosibirsk, 1991), esp. 4–7.

12. “Ob utverzhdenii Tipovogo ustava sadovodcheskogo tovarishchestva” (11 Nov. 1986), SPP RSFSR, no. 18 (1986), art. 132.

13. “O merakh po dal’neishemu razvitiiu kollektivnogo sadovodstva i ogorodnichestva v RSFSR” (5 June 1986), SPP RSFSR, no. 20 (1986), art. 149.

14. “Ob utverzhdenii Tipovogo ustava sadovodcheskogo tovarishchestva” (31 March 1988), SPP RSFSR no. 10 (1988), art. 45.

15. “O sozdanii kompleksnykh torgovo-zakupochnykh punktov v sadovodcheskikh i sadovo-ogorodnykh tovarishchestvakh” (6 Apr. 1989), SPP RSFSR, no. 11 (1989), art. 56.

16. V. S. Zakharov, “Ochered’ na lono prirody,” Nedelia, no. 40 (1988).

17. Sotsial’noe razvitie SSSR: Statisticheskii sbornik (Moscow, 1990), 207.

18. “O pervoocherednykh zadachakh po realizatsii zemel’noi reformy,” in Dachniki: Vash dom, sad i ogorod (a newspaper published in the Moscow region), no. 1 (1991), 3.

19. Simon Clarke et al., “The Russian Dacha and the Myth of the Urban Peasant,” paper posted at <http://www.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/complabstuds/russia/russint.htm>.

20. “O dopolnitel’nykh merakh po razvitiiu lichnykh podsobnykh khoziaistv grazhdan, kollektivnogo sadovodstva i ogorodnichestva,” SPP RSFSR, no. 22 (1987), art. 135.

21. “O dal’neishem razvitii podsobnykh sel’skikh khoziaistv predpriiatii, organizatsii i uchrezhdenii” (14 Oct. 1987), SPP RSFSR, no. 21 (1987), art. 131. Hitches in the implementation of the policy were also mentioned in Ustiukova, Lichnoe podsobnoe khoziaistvo, 3–4; this book went on to note (5–6) that a more precise definition of “nonlabor income” (netrudovoi dokhod) was required.

22. “O pervoocherednykh merakh po obespecheniiu zhitelei g. Moskvy zemel’nymi uchastkami dlia organizatsii kollektivnogo sadovodstva i ogorodnichestva” (22 Feb. 1991), SPP RSFSR, no. 12 (1991), art. 159.

23. See, e.g., the complaints referred to in the resolution of 5 July 1989 “O dopolnitel’nykh merakh po razvitiiu lichnykh podsobnykh khoziaistv grazhdan, kollektivnogo sadovodstva i ogorodnichestva. . . ,” SPP RSFSR, no. 18 (1989), art. 104.

24. Research note contributed by Denis Shaw to “News Notes,” Soviet Geography 32 (1991): 361.

25. Gavriil Popov, interviewed in “Khod konem?” Dachniki: Vash dom, sad i ogorod, no. 1 (1991), 2.

26. V. V. Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod: Kliuchevye elementy zhizneustroistva,” Mir Rossii, no. 4 (1997), 81.

27. The next step, however—from life ownership (vladenie) to unconditional ownership (sobstvennost’)—was considerably more problematic and caused fierce political debates in the Yeltsin-era Duma: see the account in S. K. Wegren, Agriculture and the State in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia (Pittsburgh, 1998), 160–66.

28. “Ob otvode zemel’nykh uchastkov v Moskovskoi oblasti dlia maloetazhnogo stroitel’stva i sadovodstva dlia zhitelei g. Moskvy i oblasti,” in Dachnoe khoziaistvo: Sbornik normativnykh aktov (Moscow, 1996). A subsequent presidential decree gave renewed support for provision of land to individual builders around the Russian Federation: see “О dopolnitel’nykh merakh po nadeleniiu grazhdan zemel’nymi uchastkami” (23 Apr. 1993), ibid.

29. See Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod,” 72, 86n.

30. Dacha—mini-ferma (Moscow, 1993).

31. Simagin, “Ekonomiko-geograficheskie aspekty,” chap. 2.

32. Iu. Nikiforova, “Mesto pod solntsem na 111-m kilometer,” in Peterburg, supplement to Argumenty i fakty, no. 31 (1997), 2.

33. V. Sergachev, “Dacha: Ot neveroiatnogo do ochevidnogo,” Birzha truda, 17–23 May 1999, 1.

34. R. Struyk and K. Angelici, “The Russian Dacha Phenomenon,” Housing Studies 11 (1996), 233–50.

35. Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod,” 73.

36. Rossiiskaia gazeta, 8 Aug. 1997, 8.

37. A. Simonenko, “Na ogorode vse ravny!” Nevskoe vremia, 15 May 1999.

38. Interesting material on the dacha habit, especially its role in the lives of a small-town intelligentsia marooned in post-Soviet conditions, can be found in A. White, “Social Change in Provincial Russia: The Intelligentsia in a Raion Center,” Europe-Asia Studies 52 (2000): 677–94 (this article takes as its case study a town in Tver’ oblast, four hours by bus from Moscow). Iaroslavl’ is a city known to me where the word “dacha” seems to be used exactly as it is in Moscow (most of the dwellings thus denoted are garden-plot houses in crowded settlements on the far bank of the Volga). The weekly publication that carries small ads in Petrozavodsk also refers to “dachas”: see “Vse”—ezhenedelnik besplatnykh chastnykh ob"iavlenii, at <http://vse.karelia.ru>. And to judge by one other Web page, the term “dacha” has made inroads as far east as Amursk: <http://www.amursk.ru/lschool/dachas.htm>.

39. Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod,” 72. It is telling that the most in-depth of the dacha periodicals in the early 1990s took “Dachniki” as its main title, even though its focus was exclusively the garden-plot dacha (and this point was specifically mentioned in the editorial of the first issue: “Obrashchenie k chitateliu,” Dachniki: Vash dom, sad i ogorod, no. 1 [1990], 2).

40. In 1998 the Center for Citizen Initiatives showed awareness of those less well equipped by pioneering a roof-top gardening scheme in St. Petersburg to help urban residents with no access to dacha plots: see <http://www.fadr.msu.ru/mirrors/www.igc.apc.org/cci/agirof.htm>.

41. Details in this and the next paragraph are taken from Clarke et al., “Russian Dacha.” Fully compatible with Clarke’s conclusions is H.T. Seeth, S. Chachnov, A. Surinov, and J. von Braun, “Russian Poverty: Muddling Through Economic Transition with Garden Plots,” World Development 26 (1998), 1611–23.

42. Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod,” 55.

43. Simagin, “Ekonomiko-geograficheskie aspekty,” chap. 2.

44. For a definition of the Soviet city as an “entirely separate category of urban settlement,” see R. A. French, “The Individuality of the Soviet City,” in The Sodalist City: Spatial Structure and Urban Policy, ed. French and F. E. I. Hamilton (Chichester, 1979), esp. 101–2. For a succinct “typology of socio-economic and environmental differentiation in the larger Soviet city,” see D. M. Smith, “The Socialist City,” in Cities after Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and Conflict in Post-Socialist Societies, ed. G. Andrusz, M. Harloe, and I. Szelenyi (Oxford, 1996), esp. 82–84.

45. On the steady erosion of the greenbelt in the 1970s and 1980s, see Colton, Moscow, 468–85.

46. For an early example, see A. Neverov, “Chem pakhnet na Medvezh’ikh ozerakh?” Moskovskii komsomolets, 15 Sept. 1990, 2. For an inside account of the boom in the dacha plot market, I am indebted to an unpublished memoir by Vadim Kulinchenko, who between 1988 and 1991 served on the ispolkom of a settlement in an area that was especially attractive to the unofficial property developers of late Soviet Russia. According to Kulinchenko, in these years the dacha “was a matter not of relaxation in the country but purely of property. The local authorities were showered with blows from everyone up to the very highest levels of state power . . . , and in the localities people buckled.”

47. I am grateful to Rachael Mann for showing me her B.A. dissertation, “Moscow’s Suburbia or Exurbia?” (University of Glasgow, 1998), where these results are laid out. My own interviews and questionnaire results suggest a similarly mixed picture.

48. See J. Bater, Russia and the Post-Soviet Scene: A Geographical Perspective (London, 1996), 150–51.

49. See Wegren, Agriculture and the State, esp. 163–64.

50. O. Kostiukova, “Dachi sovetskikh pisatelei po-prezhnemu v tsene,” Segodnia, 8 June 1998.

51. D. Zhelobanov and A. Grigor’ev, “Dachniki i dachevladel’tsy ishchut drug druga bez posrednikov,” Delovoi Peterburg, 26 May 1999.

52. The statistical comparison is made in Struyk and Angelici, “Russian Dacha Phenomenon,” 247.

53. A. Aleksandrova, “Novoe dachnoe myshlenie,” Obshchaia gazeta, 31 July 6 Aug. 1997. Note also glossy lifestyle magazines such as Dom & dacha (put out by the Burda publishing house from 1995), and the dacha furniture advertised at <http://www.dos.ic.sci-nnov.ru/gorodez/english/str31.htm>. The commitment of New Russians to what they probably thought of as a manorial way of life at the dacha is suggested by their common insistence on wood-fired heating rather than the much more low-maintenance gas (thanks to Judith Pallot for this observation).

54. Struyk and Angelici, “Russian Dacha Phenomenon,” 243.

55. In 1999, for example, dacha designs were displayed at an exhibition in Saratov (a selection of the designs were posted at <http://www.expo.saratov.ru/rism>).

56. On abandoned plots in Leningrad oblast, see R. Maidachenko, “Est’ svobodnye uchastki,” SPb ved, 27 Apr. 1999.

57. Vagin, “Russkii provintsial’nyi gorod,” 75–76.

58. Struyk and Angelici, “Russian Dacha Phenomenon,” 240.

59. Nikiforova, “Mesto pod solntsem,” 2.

60. “Iuridicheskaia konsul’tatsiia,” Dachnyi kaleidoskop, no. 7–8 (1992), 1.

61. “Voina na ogorodakh,” Dachnyi kaleidoskop, no. 9–10 (1992), 1.

62. Vera Popova, “Zona vne zakona,” Chas u dachi, no. 2, supplement to Peterburgskii chas pik, 6 May 1999.

63. “Ob osnovakh federal’noi zhilishchnoi sfery” (24 Dec. 1992), sec. 2, art. 9, in Dachnoe khoziaistvo, 80; N. Kalinin, “Dacha dolzhna byt’ ‘V zakone,’” Trud, 11 Nov. 1997.

64. A. Litvinov, “Kommunalki na bolote,” Rossiiskaia gazeta, 8 Aug. 1997, 8.

65. Note, e.g., the presidential decree “O gosudarstvennoi podderzhke sadovodov, ogorodnikov i vladel’tsev lichnykh podsobnykh khoziaistv” (7 June 1996), in Dachnoe khoziaistvo, 45.

66. An early discussion of the issues (which centers on the implications of the RSFSR Land Code for occupiers of garden plots) is to be found in “Nadezhnuiu zashchitu pravam sadovodov,” Dachniki: Vash dom, sad i ogorod, no. 11 (1991), 3.

67. M. P. Baumgartner, The Moral Order of a Suburb (New York, 1988).

68. See the headline exhortation “Leto—eto otdykh, leto—eto trud,” Dachnaia gazeta (Stavropol’), no. 11 (1992), 1; and M. Nikolaeva, “Pervaia zapoved’—khranit’ i vozdelyvat’ sad,” Dachnyi sezon: Gazeta dlia ural’skikh sadovodov i ogorodnikov (Cheliabinsk), no. 9 (1998), 1.

69. This attitude is nicely captured by Nancy Ries, with specific reference to the Russian language: Russian Talk: Culture and Conversation during Perestroika (Ithaca, N.Y., 1997), 30.

70. Irina Chekhovskikh, interview no. 5, p. 7 (see “Note on Sources”).

71. Ibid., interview no. 1, p. 6.

72. Ries, Russian Talk, 133–35. A more in-depth anthropological account of the post-Soviet dacha is R. Hervouet, “‘Etre à la datcha’: Eléments d’analyse issus d’une recherche exploratoire,” in Le Belarus: L’etat de l’exception, ed. F. Depelteau and A. Lacassagne (Sainte-Foy, Québec, forthcoming). This article draws attention to the subjective, as opposed to economic, motivations that underlie the dacha habit, and to the opportunities it brings for individual agency and self-affirmation. Thanks to Ronan Hervouet for letting me see his work in advance of publication.

73. These points are argued well in A. Vysokovskii, “Will Domesticity Return?” in Russian Housing in the Modern Age: Design and Social History, ed. W. C. Brumfield and B. Ruble (Cambridge, 1993).

74. Clarke et al., “Russian Dacha.”

75. Gavriil Popov, interviewed in “Khod konem?” Dachniki: Vash dom, sad i ogorod, no. 1 (1991), 2.

76. “Limonov khochet razbit’ divan Oblomova,” Smena, 5 Dec. 1996.