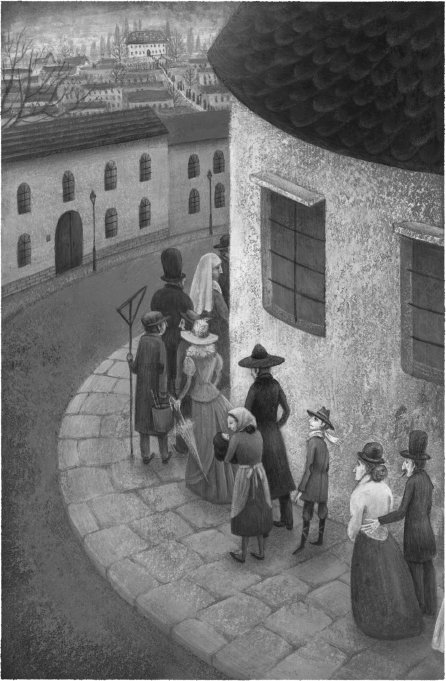

On the first Saturday of the month, the city of Baltese turned out to see the elephant. The line snaked from the home of the countess Quintet out into the street and down the hill as far as the eye could see. There were young men with waxed mustaches and pomaded hair and old ladies dressed in borrowed finery, their wrinkled faces scrubbed clean. There were candle makers who smelled of warm beeswax, washerwomen with roughened hands and hopeful faces, babies still at their mothers’ breasts, and old men who leaned heavily on canes.

Milliners stood with their heads held high, their latest creations displayed proudly on their heads. Lamplighters, their eyes heavy from lack of sleep, stood next to street sweepers, who held their brooms before them as if they were swords. Priests and fortunetellers stood side by side and eyed each other with distaste and wariness.

Everyone, it seemed, was there: the whole city of Baltese stood in line to see the elephant.

And everyone, each person, had hopes and dreams, wishes for revenge, and desires for love.

They stood together.

They waited.

And secretly, deep within their hearts, even though they knew it could not truly be so, they each expected that the mere sight of the elephant would somehow deliver them, would make their wishes and hopes and desires come true.

Peter stood in line directly behind a man who was dressed entirely in black and who had atop his head a black hat with an exceptionally wide brim. The man rocked from heel to toe, muttering, “The dimensions of an elephant are most impressive. The dimensions of an elephant are impressive in the extreme. I will now detail for you the dimensions of an elephant.”

Peter listened carefully, because he would have liked very much to know the actual dimensions of an elephant. It seemed like good information to have, but the man in the black hat never arrived at the point of announcing the figures. Instead, after insisting that he would detail the dimensions, he paused dramatically, took a deep breath, and then began again, rocking from heel to toe and saying, “The dimensions of an elephant are most impressive. The dimensions of an elephant are impressive in the extreme. . . .”

The line inched slowly forward, and mercifully, late in the afternoon, the black-hatted man’s mutterings were eclipsed by the music of a beggar who stood, singing, his hand outstretched, a black dog at his side.

The beggar’s voice was sweet and gentle and full of hope. Peter closed his eyes and listened. The song placed a steady hand on his heart. It comforted him.

“Look, Adele,” sang the beggar. “Here is your elephant.”

Adele.

Peter turned his head and looked directly at the beggar, and the man, incredibly, sang her name again.

Adele.

“Let him hold her,” his mother had said to the midwife the night that the baby was born, the night that his mother died.

“I do not think I should,” said the midwife. “He is too young himself.”

“No, let him hold her,” his mother said.

And so the midwife gave him the crying baby. And he held her.

“This is what you must remember,” said his mother. “She is your sister, and her name is Adele. She belongs to you, and you belong to her. That is what you must remember. Can you do that?”

Peter had nodded.

“You will take care of her?”

Peter had nodded again.

“Can you promise me, Peter?”

“Yes,” he had said, and then he said that terrible, wonderful word once more, in case his mother had not heard him: “Yes.”

And Adele, as if she had heard and understood him, too, had stopped crying.

Peter opened his eyes. The beggar was gone, and from ahead of him in line came the now achingly familiar words, “The dimensions of an elephant . . .”

Peter took off his hat and put it back on again and then took it off, working hard at keeping the tears inside.

He had promised.

He had promised.

He received a shove from behind.

“Are you juggling your hat, or are you waiting in line?” said a gruff voice.

“Waiting in line,” said Peter.

“Well, then, move forward, why don’t you?”

Peter put his hat on his head and stepped forward smartly, like the soldier, the very good soldier, he had once trained to become.

In the home of the count and countess Quintet, inside the ballroom, as the people filed by her, touching her, pulling at her, leaning against her, spitting, laughing, weeping, praying, and singing, the elephant stood brokenhearted.

There were too many things that she did not understand.

Where were her brothers and sisters? Her mother?

Where was the long grass and the bright sun? Where were the hot days and the dark pools of shade and the cool nights?

The world had become too cold and confusing and chaotic to bear.

She stopped reminding herself of her name.

She decided that she would like to die.