Hans Ickman pushed Madam LaVaughn’s wheelchair, and Leo Matienne had hold of Peter’s hand. The four of them moved quickly through the snowy streets. They were heading to the home of the countess.

“I do not understand,” said Madam LaVaughn. “I find this all highly irregular.”

“I believe the time has come,” said Hans Ickman.

“The time? The time? The time for what?” said Madam LaVaughn. “Do not speak to me in riddles.”

“The time for you to return to the prison.”

“But it is the middle of the night, and the prison is that way,” said Madam LaVaughn, flinging a heavily bejeweled hand behind her. “The prison is in entirely the opposite direction.”

“There is something else that we must tend to first,” said Leo Matienne.

“And what is that?” said Madam LaVaughn.

“We must retrieve the elephant from the home of the countess,” said Peter, “and take her to the magician.”

“Retrieve the elephant?” said Madam LaVaughn. “Retrieve the elephant? Take the elephant to the magician? Is he mad? Is the boy mad? Is the policeman mad? Has everyone gone mad?”

“Yes,” said Hans Ickman after a long moment. “I believe that is the case. Everyone has gone a little mad.”

“Oh,” said Madam LaVaughn, “very well. I see.”

They were silent together then: the noblewoman and her servant, the policeman and the boy walking beside him. There was only the sound of the wheelchair moving through the snow and three pairs of footsteps striking the muffled cobblestones.

It was Madam LaVaughn who at last broke the silence. “Highly irregular,” she said, “but quite interesting, very interesting indeed. Why, it seems as if anything could happen, anything at all.”

“Exactly,” said Hans Ickman.

In the prison, in his small cell, the magician paced back and forth. “And if they succeed?” he said. “If they manage, somehow, to bring the elephant here? Then there is no helping it. I must speak the words. I must try to cast the spell again. I must work to send her back.”

The magician paused in his pacing and looked up and out his window and was amazed to see snowflake after snowflake dancing through the air.

“Oh, look,” he said, even though he was alone. “It is snowing — how beautiful.”

The magician stood very still. He stared at the falling snow.

And suddenly, he did not care at all that he would have to undo the greatest thing he had ever done.

He had been so lonely, so desperately, hopelessly lonely for so long. He might very well spend the rest of his life in prison, alone. And he understood that what he wanted now was something much simpler, much more complicated than the magic he had performed. What he wanted was to turn to somebody and take hold of their hand and look up with them and marvel at the snow falling from the sky.

“This,” he wanted to say to someone he loved and who loved him in return. “This.”

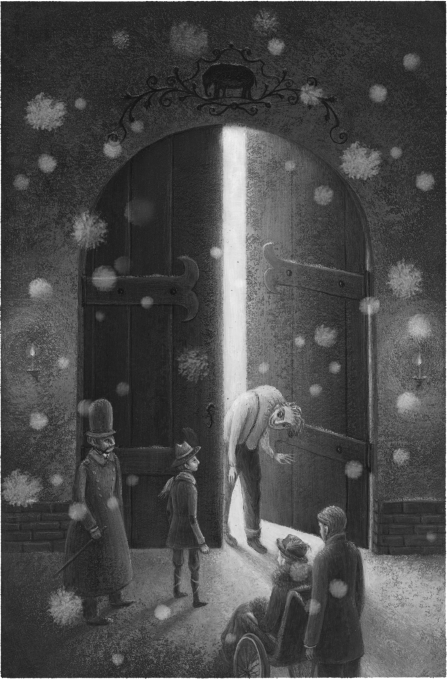

Peter and Leo Matienne and Hans Ickman and Madam LaVaughn stood outside the home of the countess Quintet; they stared together at the massive, imposing elephant door.

“Oh,” said Peter.

“We will knock,” said Leo Matienne. “That is where we will begin, with knocking.”

“Yes,” said Hans Ickman. “We will knock.”

The three of them stepped forward and began to pound on the door.

Time stopped.

Peter had a terrible feeling that the whole of his life had been nothing but standing and knocking, asking to be let into some place that he was not even certain existed.

His fingers were cold. His knuckles hurt. The snow fell harder and faster.

“Perhaps this is a dream,” said Madam LaVaughn from her chair. “Perhaps the whole thing has been nothing but a dream.”

Peter remembered the door in the wheat field. He remembered holding Adele. And then he remembered the terrible, heartbroken look in the elephant’s eyes.

“Please!” he shouted. “Please, you must let us in.”

“Please!” shouted Leo Matienne.

“Yes,” said Hans Ickman, “please.”

And from the other side of the door came the screech of a dead bolt being thrown. And then another and another. And slowly, as if it were reluctant to do so, the door began to open. A small, bent man appeared. He stepped outside and looked up at the falling snow and laughed.

“Yes,” he said. “You knocked?”

And then he laughed again.

Bartok Whynn laughed even harder when Peter told him why they had come.

“You want — ha, ha, hee — to take the elephant from here to the — ha, ha, hee, wheeeeee — to the magician in prison so that the magician may perform the magic to send the elephant — wheeeeee — home?”

He laughed so hard that he lost his balance and had to sit down in the snow.

“Whatever is so funny?” said Madam LaVaughn. “You must tell us so that we may laugh along with you.”

“You may laugh along with me,” said Bartok Whynn, “only if you find it funny to — ha, ha, hee — think of me dead. Imagine if the countess were to wake tomorrow and find that her elephant had disappeared, and that I, Bartok Whynn, was the one — ha, ha, hee — who had allowed the beast to be spirited away?”

The little man was shaken by a hilarity so profound that his laughter disappeared altogether, and no sound at all came from his open mouth.

“But what if you were not here, either?” said Leo Matienne. “What if you, too, were gone on the morrow?”

“What is that?” said Bartok Whynn. “What did you — ha, ha, hee — say?”

“I said,” said Leo Matienne, “what if you, like the elephant, were gone to the place you were meant, after all, to be?”

Bartok Whynn stared up at Leo Matienne and Hans Ickman and Peter and Madam LaVaughn. They were all holding very still, waiting. He held still, too, and considered them, gathered together there in the falling snow.

And in the silence he at last recognized them.

They were the figures from his dream.

In the ballroom of the countess Quintet, when the elephant opened her eyes and saw the boy standing before her, she was not at all surprised.

She thought simply, You. Yes, you. I knew that you would come for me.