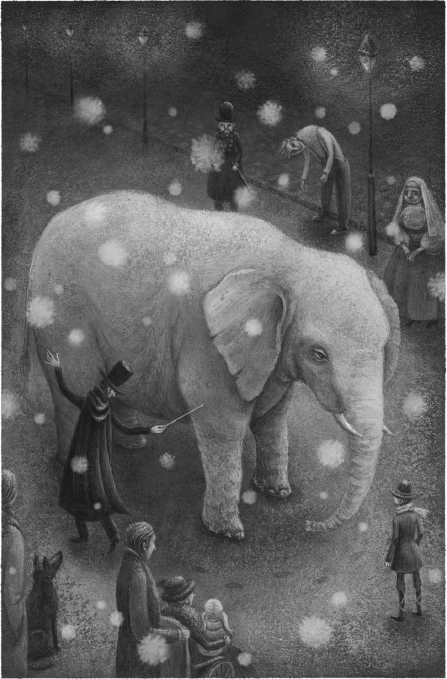

Peter walked in front of the elephant. He carried Adele. Next to Peter walked Leo Matienne. Behind the elephant was Madam LaVaughn in her wheelchair, pushed by Hans Ickman, who was, in turn, followed by Bartok Whynn, and behind him was the beggar, Tomas, with Iddo at his heels. At the very end was Sister Marie, who for the first time in fifty years was not at the door of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light.

Peter led them, and as he walked through the snowy streets, each lamppost, each doorway, each tree, each gate, each brick leaped out at him and spoke to him. All the things of the world were things of wonder that whispered to him the same thing. Each object spoke the words of the fortuneteller and the hope of his heart that had turned out, after all, to be true: she lives, she lives, she lives.

And she did live! Her breath was warm on his cheek.

She weighed nothing.

Peter could have happily carried her in his arms for all eternity.

The cathedral clock tolled midnight. A few minutes after the last note, the magician heard the great outer door of the prison open and then close again. The sound of footsteps echoed down the corridor. The steps were accompanied by the jangle of keys.

“Who comes now?” shouted the magician. “Announce yourself!”

There was no answer, only footsteps and the light from the lantern. And then the policeman came into view. He stood in front of the magician’s cell and held up the keys and said, “They await you outside.”

“Who?” said the magician. “Who awaits me?” His heart thumped in disbelief.

“Everyone,” said Leo Matienne.

“You succeeded? You brought the elephant here? And Madam LaVaughn as well?”

“Yes,” said the policeman.

“Merciful,” said the magician. “Oh, merciful. And now it must be undone. Now I must try to undo it.”

“Yes, now it all rests upon you,” said Leo. He inserted the key into the lock and turned it and pushed open the door to the magician’s cell.

“Come,” said Leo Matienne. “We are, all of us, waiting.”

There is as much magic in making things disappear as there is in making them appear. More, perhaps. The undoing is almost always more difficult than the doing.

The magician knew this full well, and so when he stepped outside into the cold and snowy night, free for the first time in months, he felt no joy. Instead, he was afraid. What if he tried and failed again?

And then he saw the elephant, the magnificence of her, the reality of her, standing there in the snow.

She was so improbable, so beautiful, so magical.

But no matter, it would have to be done. He would have to try.

“There,” said Madam LaVaughn to Adele, who was in the noblewoman’s lap, wrapped up tight and warm, “there he is. That is the magician.”

“He does not look like a bad man,” said Adele. “He looks sad.”

“Yes, well, I am crippled,” said Madam LaVaughn, “and that, I assure you, goes somewhat beyond sadness.”

“Madam,” said the magician. He turned away from the elephant and bowed to Madam LaVaughn.

“Yes?” she said to him.

“I intended lilies,” said the magician.

“Perhaps you do not understand,” said Madam LaVaughn.

“Please,” said Hans Ickman, “please, I beg you! Speak from your hearts.”

“I intended lilies,” continued the magician, “but in the clutches of a desperate desire to do something extraordinary, I called down a greater magic and inadvertently caused you a profound harm. I will now try to undo what I have done.”

“But will I walk again?” said Madam LaVaughn.

“I do not think so,” said the magician. “But I beg you to forgive me. I hope that you will forgive me.”

She looked at him.

“Truly, I did not intend to harm you,” he said. “That was never my intention.”

Madam LaVaughn sniffed. She looked away.

“Please,” said Peter, “the elephant. It is so cold, and she needs to go home, where it is warm. Can you not do your magic now?”

“Very well,” said the magician. He bowed again to Madam LaVaughn. He turned to the elephant. “You must, all of you, step away, step back. Step back.”

Peter put his hand on the elephant. He let it rest there for a moment. “I’m sorry,” he said to her. “And I thank you for what you did. Thank you and good-bye.” And then he stepped away from her, too.

The magician walked, circling the elephant and muttering to himself. He thought about the star on view from his prison cell. He thought about the snow falling at last, and how what he had wanted more than anything was to show it to someone. He thought about Madam LaVaughn’s face looking up into his, questioning, hoping.

And then he began to speak the words of the spell. He said the words backward, and he said the spell backward, too. He said it, all of it, under his breath, with the profound hope that it would well and truly work, and with the knowledge, too, that there was only so much, after all, that could be undone, even by magicians.

He spoke the words.

The snow stopped.

The sky became suddenly, miraculously clear, and for a moment the stars, too many of them to count, shone bright. The planet Venus sat among them, glowing solemnly.

It was Sister Marie who noticed. “Look there,” she said. “Look up.” She pointed at the sky. They all looked: Bartok Whynn, Tomas, Hans Ickman, Madam LaVaughn, Leo Matienne, Adele.

Even Iddo raised his head.

Only Peter kept his eyes on the elephant and the magician who was walking around and around her, muttering the backward words of a backward spell that would send her home.

And so Peter was the only one to see her leave. He was the only one to witness the greatest magic trick that the magician ever performed.

The elephant was there, and then she was not.

It was as simple as that.

As soon as she was gone, the clouds returned, the stars disappeared from view, and it began, again, to snow.

It is incredible that the elephant, who had arrived in the city of Baltese with so much noise, left it in such a profound silence. When she at last disappeared, there was no noise at all, only the tic-tic-tic of the falling snow.

Iddo put his nose up in the air and sniffed. He let out a low, questioning bark.

“Yes,” Tomas said to him, “gone.”

“Ah, well,” said Leo Matienne.

Peter bent over and looked at the four circular footprints left in the snow. “She is truly gone,” he said. “I hope she is home.”

When he raised his head, Adele was looking at him, her eyes round and astonished.

He smiled at her. “Home,” he said.

And she smiled back at him, that same smile: disbelief, then belief, and finally joy.

The magician sank to his knees and put his head in his shaking hands. “I am done with it then, all of it. And I am sorry. Truly, I am.”

Leo Matienne took hold of the magician’s arm and pulled him to his feet.

“Are you going to put him back in prison?” said Adele.

“I must,” said Leo Matienne.

And then Madam LaVaughn spoke. She said, “No, no. It is pointless, after all, is it not?”

“What?” said Hans Ickman. “What did you say?”

“I said that it is pointless to return him to prison. What has happened has happened. I release him. I will press no charges. I will sign any and all statements to that effect. Let him go. Let him go.”

Leo Matienne let go of the magician’s arm, and the magician turned to Madam LaVaughn and bowed. “Madam,” he said.

“Sir,” she said back.

They let him walk away.

They watched his black coat retreating slowly into the swirling snow. They watched, together, until it disappeared entirely from view.

And when he was gone, Madam LaVaughn felt some great weight suddenly flap its wings and break free of her. She laughed aloud. She put her arms around Adele and hugged her tight.

“The child is cold,” she said. “We must go inside.”

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne. “Let’s go inside.”

And that, after all, is how it ended.

Quietly.

In a world muffled by the gentle, forgiving hand of snow.