THERE YOU ARE, MILADY. MEET THE rabbit doll,” said Lucius.

The doll mender walked away, turning out the lights one by one.

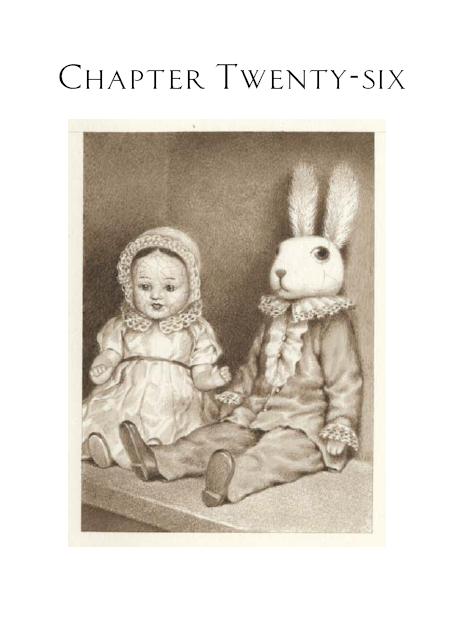

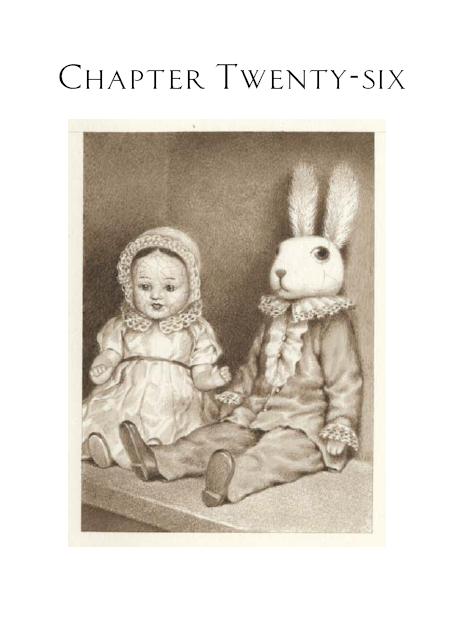

In the gloom of the shop, Edward could see that the doll’s head, like his, had been broken and repaired. Her face was, in fact, a web of cracks. She was wearing a baby bonnet.

“How do you do?” she said in a high, thin voice. “I am pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“Hello,” said Edward.

“Have you been here long?” she asked.

“Months and months,” said Edward. “But I don’t care. One place is the same as another to me.”

“Oh, not for me,” said the doll. “I have lived one hundred years. And in that time, I have been in places that were heavenly and others that were horrid. After a time, you learn that each place is different. And you become a different doll in each place, too. Quite different.”

“One hundred years?” said Edward.

“I am old. The doll mender confirmed this. He said as he was mending me that I am at least that. At least one hundred. At least one hundred years old.”

Edward thought about everything that had happened to him in his short life. What kind of adventures would you have if you were in the world for a century?

The old doll said, “I wonder who will come for me this time. Someone will come. Someone always comes. Who will it be?”

“I don’t care if anyone comes for me,” said Edward.

“But that’s dreadful,” said the old doll. “There’s no point in going on if you feel that way. No point at all. You must be filled with expectancy. You must be awash in hope. You must wonder who will love you, whom you will love next.”

“I am done with being loved,” Edward told her. “I’m done with loving. It’s too painful.”

“Pish,” said the old doll. “Where is your courage?”

“Somewhere else, I guess,” said Edward.

“You disappoint me,” she said. “You disappoint me greatly. If you have no intention of loving or being loved, then the whole journey is pointless. You might as well leap from this shelf right now and let yourself shatter into a million pieces. Get it over with. Get it all over with now.”

“I would leap if I was able,” said Edward.

“Shall I push you?” said the old doll.

“No, thank you,” Edward said to her. “Not that you could,” he muttered to himself.

“What’s that?”

“Nothing,” said Edward.

The dark in the doll shop was now complete. The old doll and Edward sat on their shelf and stared straight ahead.

“You disappoint me,” said the old doll.

Her words made Edward think of Pellegrina: of warthogs and princesses, of listening and love, of spells and curses. What if there was somebody waiting to love him? What if there was somebody whom he would love again? Was it possible?

Edward felt his heart stir.

No, he told his heart. Not possible. Not possible.

In the morning, Lucius Clarke came and unlocked the shop, “Good morning, my darlings,” he called out to them. “Good morning, my lovelies.” He pulled up the shades on the windows. He turned on the light over his tools. He switched the sign on the door to OPEN.

The first customer was a little girl with her father.

“Are you looking for something special?” Lucius Clarke said to them.

“Yes,” said the girl, “I am looking for a friend.”

Her father put her on his shoulders and they walked slowly around the shop. The girl studied each doll carefully. She looked Edward right in the eyes. She nodded at him.

“Have you decided, Natalie?” her father asked.

“Yes,” she said, “I want the one in the baby bonnet.”

“Oh,” said Lucius Clarke, “you know that she is very old. She is an antique.”

“She needs me,” said Natalie firmly.

Next to Edward, the old doll let out a sigh. She seemed to sit up straighter. Lucius came and took her off the shelf and handed her to Natalie. And when they left, when the girl’s father opened the door for his daughter and the old doll, a bright shaft of early morning light came flooding in, and Edward heard quite clearly, as if she were still sitting next to him, the old doll’s voice.

“Open your heart,” she said gently. “Someone will come. Someone will come for you. But first you must open your heart.”

The door closed. The sunlight disappeared.

Someone will come.

Edward’s heart stirred. He thought, for the first time in a long time, of the house on Egypt Street and of Abilene winding his watch and then bending toward him and placing it on his left leg, saying: I will come home to you.

No, no, he told himself. Don’t believe it. Don’t let yourself believe it.

But it was too late.

Someone will come for you.

The china rabbit’s heart had begun, again, to open.