THE MURDER OF MARILYN SHEPPARD, 1954

DID SAM DO IT?

Dr. Sam Sheppard and his wife, Marilyn, seemed to have an ideal home and marriage—until a savage murder revealed the dark undercurrents in their “perfect life.”

The murder of Marilyn Sheppard and the subsequent trial of her prosperous, good-looking doctor husband has cast a long shadow. The novelist Ernest Hemingway wrote: “A trial like this, with its elements of doubt, is the greatest human story of all… This is the real thing. This trial has everything the public clamors for.”

As day broke on July 4, 1954, Marilyn Sheppard was bludgeoned to death with an unknown instrument in the bedroom of the couple’s idyllic home. With her husband the prime suspect, the shocking murder led to one of the longest and most controversial murder investigations and trials in American legal history.

A PERFECT EVENING

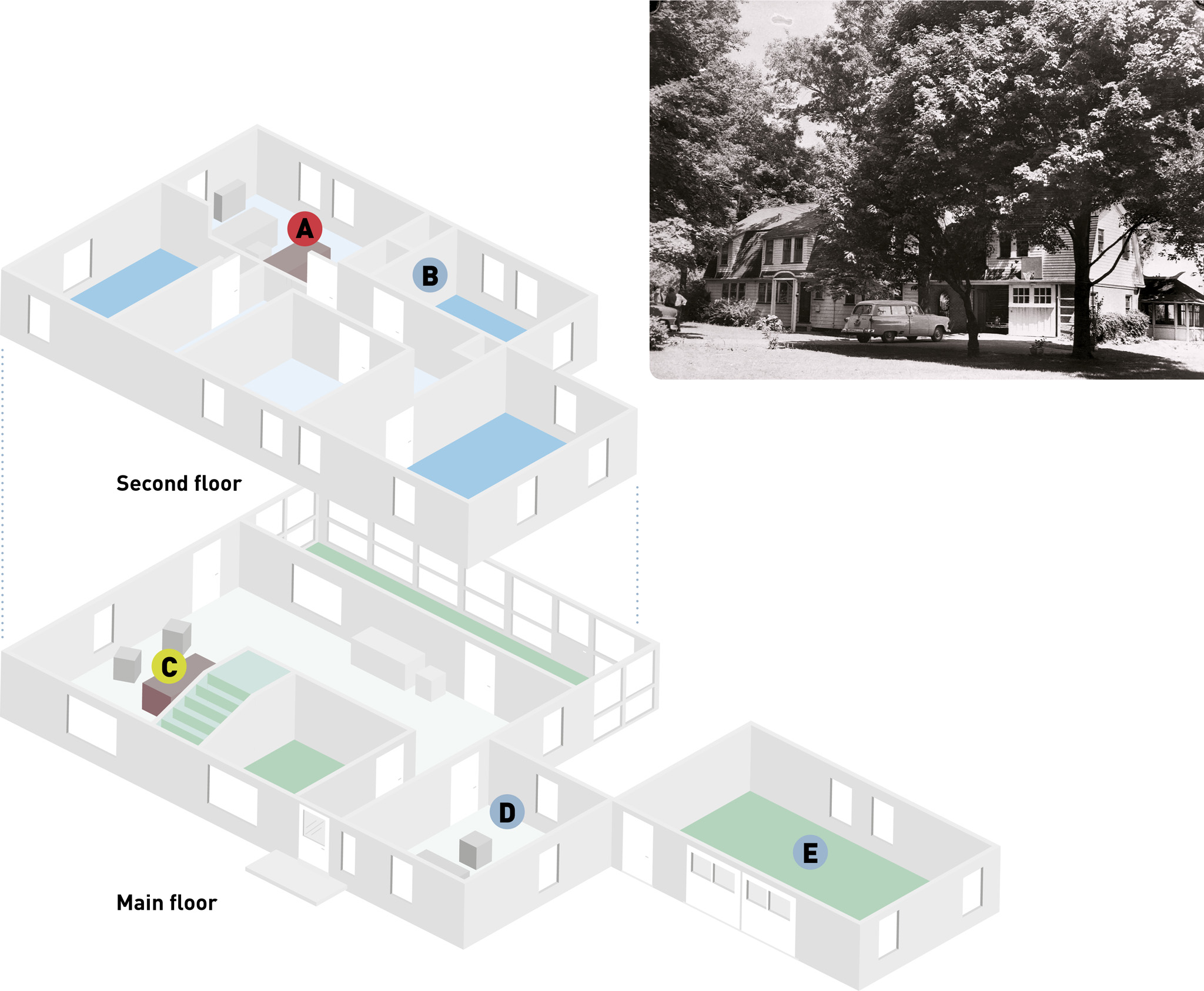

Osteopath Dr. Sam Sheppard lived in a two-story, Dutch Colonial home in the leafy suburb of Bay Village, Ohio, overlooking Lake Erie. His wife, Marilyn, was a Sunday school teacher, and they had a young son, Samuel, nicknamed Chip. Marilyn was four months pregnant with their second child. On the evening of July 3, 1954, Sam and Marilyn were entertaining neighbors. They ate dinner together before watching the sun set over Lake Erie’s still waters. At dusk, they went indoors to watch the 1945 movie Strange Holiday. Dr. Sheppard, exhausted from a busy day at his surgical practice, later dozed off in a daybed in the living room. The neighbors left around midnight, and Marilyn went upstairs to their bedroom, leaving her husband asleep. She removed her nail polish and went to bed, leaving the bedside light on in case Sheppard woke up and came upstairs. When her husband was working late, Marilyn would often leave the light on for his late-night return. What happened next has baffled the world for more than half a decade.

Main images: Marilyn and Sam Sheppard on their wedding day in 1945.

Clockwise from top: The crime scene; Sam Sheppard in a neck brace during his trial for murder; Susan Hayes, Sheppard’s lover; witnesses Esther Houk and J. Spencer Houk, the Sheppards’ Bay Village neighbors.

INTRUDER TERROR

According to Sheppard, he was awoken at approximately 4:00 a.m. by Marilyn screaming his name. He added: “It wasn’t actually a scream. I can’t really explain it.” He said that he ran upstairs to the bedroom, where he grappled with “a white form” before being struck on the back of the head and knocked out. When Sheppard regained his senses, he heard noises downstairs. He rushed to where the noise was coming from and discovered a “bushy-haired man” running away from the house. He pursued this intruder through the garden and down to the shores of the lake, where a struggle ensued. During this altercation, Sheppard was knocked unconscious once again.

When he came to, the man was gone. Sheppard ran back to the house to check on his wife and son, relieved to find that Chip was sleeping soundly and had been seemingly undisturbed through the entire ordeal. However, when Sheppard entered his and Marilyn’s bedroom, he found the body of his wife sprawled on the bed, her brown hair matted in a puddle of her own blood. She had been attacked with such force and hit repeatedly—later estimated to be between 27 and 35 times—that the bones below her eye and around her mouth were detached from her face. Her nose was broken, two teeth were missing and a nail on her left hand had been torn away, presumably when she was desperately trying to defend herself against her attacker. Her pajama top was lifted up above her breasts, and her underwear had been removed and was dangling from her right leg. The bedroom walls were spattered with blood.

As news of the gruesome murder made headlines across the country, Leo Stawicki—a neighbor of the Sheppards—contacted police to inform them that he had spotted a strange man near the Sheppards’ home in the early hours of the day that Marilyn was killed. He said he spotted the man as he was returning from a fishing trip in Sandusky at around 2:30 a.m. As his headlights illuminated the road, Leo saw him standing by the side of the road in front of the Sheppards’ house. He described the man as tall, bushy-haired, and wearing a white shirt. This description matched the one given by Sam of the man he had fought with in the bedroom and later on the shore front. Two more witnesses, Richard and Betty Knitter, would later testify that they had also seen a man with bushy hair outside the Sheppard home at around 3:00 a.m. “He had a terrified look on his face,” Richard said.

Nevertheless, the police soon announced that they had essentially ruled out any theory of a “casual” intruder. Although a doctor had concluded that Dr. Sheppard couldn’t have inflicted the wounds he sustained on himself, investigators now suspected that he had fabricated the story of the fracas with an intruder and had killed his wife himself. The Sheppards’ son had remained asleep next door during the entire attack, and it seemed that the family dog, Koko, remained silent throughout the night.

TRIAL BY NEWSPAPER

To make matters worse for Sheppard, conservative Cleveland was shocked by revelations that his marriage was not as happy as it at first appeared, and that the doctor had had at least one extramarital affair—which he initially denied. Newspapers began to run headlines such as: “Why Isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?”1

Two weeks after Marilyn’s murder, Dr. Sheppard was arrested, and the first trial began in Ohio on October 18, 1954. Newspapers and TV stations covered it extensively; the judge, Edward J. Blythin, admitted to one newspaper columnist his belief that Dr. Sheppard was “guilty as hell” before any evidence was even presented. The upper-class lifestyle of the Sheppards added an element of glamor to the already sensational trial; it was to the 1950s what the O. J. Simpson trial would become to the 1990s.

December 21, 1954 / Dr. Sheppard is convicted of murder but proclaims his innocence to the court.

During the trial, the prosecution claimed that there were no signs of forced entry to the house. A report listing a damaged door in the basement was not disclosed. Trauma expert Dr. William Fallon described Sheppard’s serious neck injuries as “almost impossible to self-inflict,” owing to the position and severity of them. He had a fracture of the vertebrae, as well as swelling at the bottom of the skull. Despite the fact that the prosecution’s case against Dr. Sheppard was entirely circumstantial, he was convicted of second-degree murder. Some might say that he was accused of murder but convicted of adultery.

However, Sheppard’s conviction was not the end of the story. Interest in the case revived in 1957 when a convict named Donald J. Welder confessed to the murder. Police dismissed his claim as fantasy; nevertheless Sheppard’s legal team continued to make numerous appeals. Sheppard was finally released on bond in 1964, after serving nine years. On June 6, 1966, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction. Lambasting the “carnival atmosphere” of the original trial, the court ruled that the judge had failed to shield jurors and witnesses from the biased media circus surrounding the case.

BACK IN COURT

A new trial was ordered, beginning on October 24, 1966. Expert Dr. Paul Leland Kirk testified that Marilyn was murdered by a left-handed killer; Sheppard was right-handed. The court did not find Sheppard guilty, but neither did it declare him innocent. When Sheppard was released, the rules under which the press could report criminal trials in the US were rewritten to prevent another “trial by newspaper” ever happening again. Dr. Sam Sheppard wrote a book about the case, published in 1966, titled Endure and Conquer: My Twelve-Year Fight for Vindication. The teaser page bore the heading “Did Sam Do It?”2

April 13, 2000/ The jury delivers its verdict in a civil suit brought by Sheppard’s son, Samuel.

In 2000, a civil case was filed by Sheppard’s son, Samuel Reese Sheppard, in an attempt to clear his father’s name. By this point, Dr. Sheppard had been deceased for 30 years, but his son was determined to have him posthumously declared innocent. If the State of Ohio declared Dr. Sheppard innocent, then Samuel could have sued the state for the wrongful conviction of his father. Over the 10-week trial, 76 witnesses were called and hundreds of exhibits were displayed.

THE BUSHY-HAIRED MAN

During the 2000 trial, plaintiff attorney Terry Gilbert offered another suspect for the murder—Richard Eberling. The owner of Dick’s Cleaning Services, Eberling was regularly hired by the Sheppards to wash their windows. He suffered from seizures and temper tantrums and was often caught lying and stealing. He started to lose his hair as a young adult, prompting him to wear hairpieces. In addition, Eberling had been convicted in 1989 of killing Ethel Mae Durkin—an elderly widow—as part of a fraudulent scheme to collect on her will.

Eberling was first connected to the murder of Marilyn Sheppard in 1959, when he was arrested for a string of robberies on Cleveland’s west side. Many of the houses that he targeted belonged to his window cleaning clients, and tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of items were stolen. One piece of particular interest to police was a diamond ring, which Eberling kept apart from the other items he accumulated. This ring once belonged to Marilyn Sheppard. Eberling claimed that he had stolen it from Dr. Sheppard’s brother’s home, where he found a box marked “Property of Marilyn Sheppard.”

Eberling went on to tell police that just days before Marilyn’s murder, he had cut his finger while changing storm windows and that he had dripped blood throughout the Sheppards’ home. Was he anticipating the need for an alibi? In February 1997, DNA in the blood found on the stairs, as well as semen found on Marilyn, was consistent with Eberling’s DNA. This DNA type was shared by approximately 5 percent of the population. Bay Village police had wanted to pursue him as a suspect at the time, but Cuyahoga County Prosecutor John T. Corrigan and Coroner Samuel R. Gerber considered the case closed.

Adding more weight to the evidence against Eberling, Robert Lee Parks—a convicted robber who was incarcerated with Eberling—told police that Eberling had confessed that he killed Marilyn and that everything Dr. Sheppard had said about the “bushy-haired intruder” was true. Eberling allegedly told Parks that he had gone to the Sheppards’ home to rob it and to rape Marilyn, thinking that Dr. Sheppard was working late. He also admitted that he was wearing a bushy-haired wig and makeup. Eberling apparently killed Marilyn when she bit him and screamed for help while he raped her. Even though no blood in the house matched the DNA profile of Dr. Sheppard and instead matched Eberling—who was also found in possession of Marilyn’s ring—the jury sided with county prosecutors and declared that they could not find Dr. Sheppard posthumously innocent of his wife’s murder.

FURTHER SUSPICIONS

While Dr. Sheppard and Richard Eberling remain the two main suspects, former FBI agent Bernard Conners, in his book Tailspin: The Strange Case of Major Call, contends that Air Force Maj. James Arlon Call killed Marilyn during a cross-country crime spree, which ended in a deadly shoot-out with police in Lake Placid, New York. Conners points to a bite wound on Call’s hand, which he believes was inflicted by Marilyn during their struggle. Conners also believes that the murder weapon was a crowbar found in Call’s possession.

F. Lee Bailey—the lawyer who won Dr. Sheppard’s second acquittal—presented Spencer and Esther Houk, neighbors of the Sheppards, as suspects. The motivation, he claimed, was that Esther caught her husband and Marilyn having an affair and killed Marilyn in a fit of rage. Bailey’s theory was presented to a grand jury but they decided against indicting the Houks, who had been dead for years.

The murder of Marilyn Sheppard gave rise to many books, inspired a hit 1960s TV series and a 1993 movie (both called The Fugitive), and led to a precedent-setting Supreme Court decision on the effects of pretrial publicity, ensuring the case a prominent place in popular culture and legal history. The “trial of the century” never proved who killed Marilyn Sheppard, leaving the case still unsolved. Following Sheppard’s release, many still considered him guilty. He lived under a cloud of suspicion and was barred from the medical profession. He fell into a haze of alcohol and drugs, and died in 1970 at the age of just 46. The cause of death was liver failure. His son, however, said the true cause was “a broken heart and a spirit that found no solace.”

THE SHEPPARD HOME

The bedroom where Marilyn died

The bedroom where Marilyn died

Chip Sheppard’s room

Chip Sheppard’s room

The daybed where Sheppard slept

The daybed where Sheppard slept

Sam’s study

Sam’s study

The garage

The garage

CASE NOTES

The bedroom where Marilyn died

The bedroom where Marilyn died Chip Sheppard’s room

Chip Sheppard’s room The daybed where Sheppard slept

The daybed where Sheppard slept Sam’s study

Sam’s study The garage

The garage