THE OAKLAND COUNTY CHILD KILLER, 1976–1977

STRANGER DANGER

Like any loving parents, those in Oakland County, Michigan, often told their children to stay away from strangers. These routine, everyday warnings were suddenly justified in the cruelest way possible.

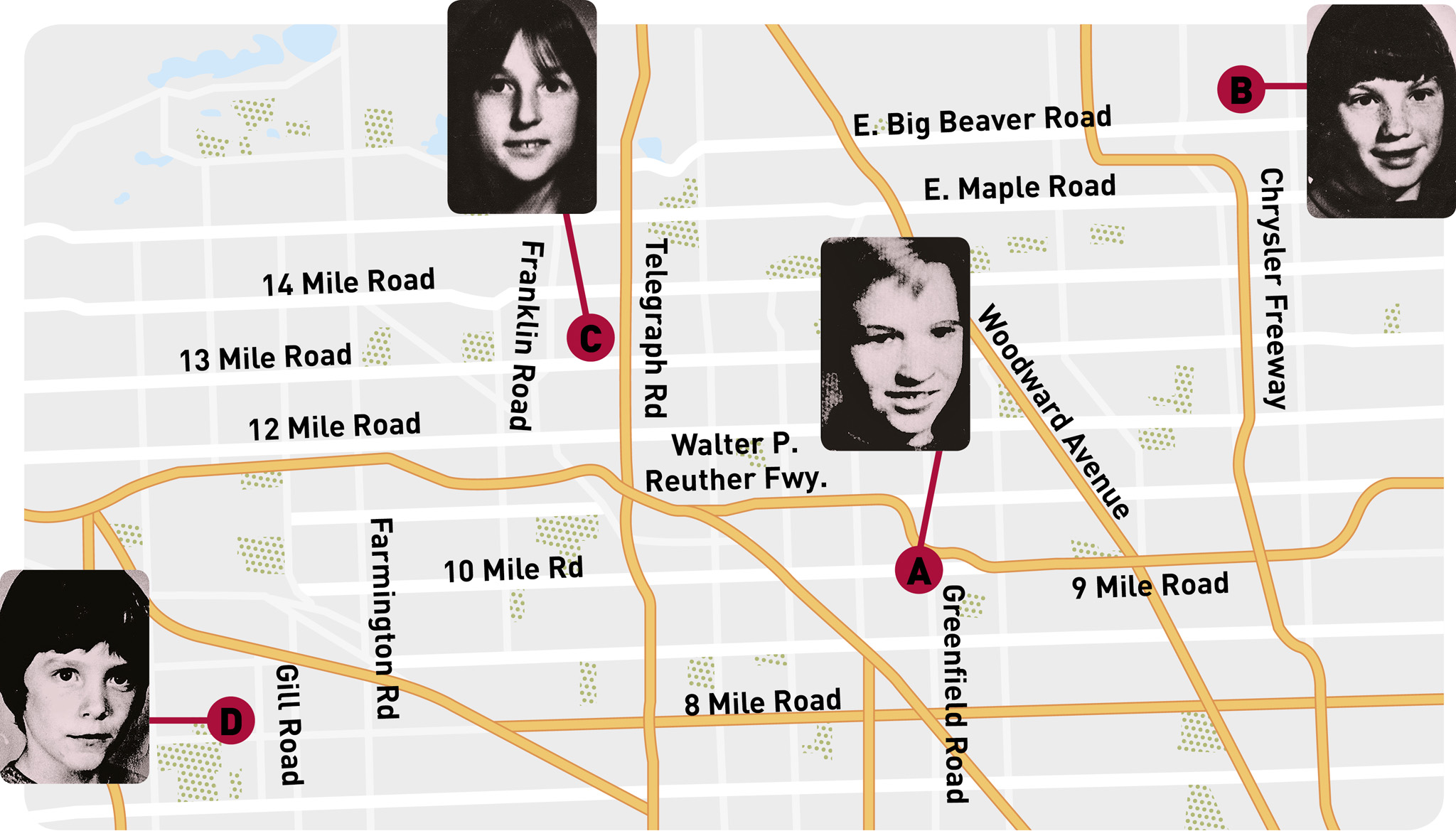

The case of the so-called Oakland County Child Killer, named after the Michigan county in which four terrifying kidnappings and murders occurred, panicked parents throughout the Midwest. The details were baffling. The two male victims bore signs of sexual assault, but the two females did not. Three were suffocated or strangled, while one died of a shotgun blast to the head. All appeared to have been bathed at some point and were discovered neatly dressed.

THE FIRST VICTIM

Twelve-year-old Mark Stebbins and his older brother Mike regularly hung out together at an American Legion Hall at 9 Mile and Woodward, about a mile from their home in Ferndale, Michigan. The veterans’ organization was a safe place for the boys to spend time, and on a snowy Sunday in February 1976, they walked to the hall to play pool.

After a while, Mark—described as a good student who liked to spend time alone—said he wanted to walk home to watch television. It was a path he had taken countless times before, both with his brother and by himself. But on this day, Mark did not arrive home, and his mother, Ruth, called police in a panic. While Mark Stebbins’ disappearance worried those who knew him, it was not the type of case that would normally receive widespread media attention. That changed four days later, when an office worker in the nearby town of Southfield spotted his body, abandoned in a parking lot.

Clockwise from top: The body of Kristine Mihelich is removed from a snowbank in Franklin Village; Timothy King; Kristine Mihelich; Mark Stebbins; Jill Robinson; artist sketch of the killer; an artist’s sketch of the killer; suspect Theodore Lamborgine.

February 19, 1976 / Mark Stebbins’ body is found.

Mark had rope burns on his wrists, but he was not bound, and it appeared that he had been strangled or suffocated at least a day earlier. Ferndale Police Chief Donald Geary told reporters the boy’s body likely had been kept in the trunk of a car before being ditched in the parking lot. Not only had he been scrubbed clean, but his fingernails had been scraped by his killer. As the police investigated and Mark’s family mourned, months passed by and the tragic case slipped quietly from the headlines.

CONNECTED KILLINGS

On December 26, 1976, a motorist found the body of 12-year-old Jill Robinson in Troy, Michigan. She had left her Royal Oak home four days earlier after a row with her mother over what to have for dinner. On the surface, it was tough to discern if Jill’s death was related to Mark’s. The little girl had died in a completely different manner—a shotgun blast to the head rather than asphyxiation. But a few striking similarities led police to believe that there must be a connection: Jill’s parents were also divorced; like Mark, she was described as a loner; and it appeared she had been kidnapped and held for days before being killed. As with Mark, she had been fed and given water to drink while held captive. Her body, like Mark’s, was dumped on a day it had snowed, helping to obscure much-needed evidence.

The killer’s pace quickened. The next victim disappeared just a week later, on January 2, 1977, after leaving a party store just four blocks from her house in nearby Berkley, Michigan. Ten-year-old Kristine Mihelich had bought a magazine and was walking along a busy thoroughfare in broad daylight when she vanished. Because Jill’s body had been found so recently, Kristine’s disappearance was treated with far more urgency. Officers canvassed the neighborhood looking for witnesses and clues but found nothing. A week after Kristine vanished, police assumed the worst—and that scared them.1

“IF SOMEONE CAN BE SNATCHED OFF A BUSY STREET AT 3:00 P.M. ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON, HOW CAN YOU PROTECT ANYONE?”

SGT. DAVID PICHE

These fears were realized when snow fell on January 22, 1977—19 days after Kristine’s disappearance. Mail carrier Jerry Wozny discovered Kristine’s body in a ditch along a dead-end road in Franklin, Michigan, another Oakland County town. “I saw a hand. It scared the hell out of me,” Wozny told reporters. He said it appeared that snow had been tossed on top of her body to make her difficult to spot.2 The headlines the next day read: SLAYINGS TERRORIZE COUNTY.3

THE FINAL DISAPPEARANCE

Less than two months later, that terror reached the King family. On March 16, 1977, 11-year-old Tim asked his sister Kathy for 30 cents so he could buy candy from a drugstore three blocks from home. He left his house in Birmingham, Michigan, at about 8:15 p.m. and skateboarded to the Hunter-Maple Pharmacy. The store clerk, Amy Walters, saw him leave with his candy at about 8:30 p.m. through a rear door that led to a darkened parking lot. Tim never returned home.

Tim King’s body was found a week later. Like the other victims, he had been kept alive much of the time he had been missing. Officials believed that he was suffocated within an hour of being found. While Tim was missing, his mother had written a letter to the Detroit News, pleading for him to come home for some Kentucky Fried Chicken, his favorite meal. An autopsy of the body revealed the food that he had eaten just before he was killed—fried chicken.

Tim’s meticulously clean body was found in a ditch along a well-traveled dirt road in Livonia, Michigan, with his skateboard placed next to it. The location marked a slight change in pattern, as Livonia fell in Wayne County, rather than neighboring Oakland. Police and sheriff’s deputies from both jurisdictions were therefore dedicated to the case.

POLICE DESCRIPTIONS

Enough witnesses finally came forward for the police to create a sketch of a suspect. The face that emerged belonged to a white man with dark hair, a prominent nose, and thick lips. Bushy muttonchops ran down his cheeks. An accompanying psychological profile told the community they were looking for someone from 20 to 35 years old, who was well-educated and worked in a white-collar job with enough flexibility to give him the freedom to carry out his terrible crimes. “We believe that he appears sane 99 percent of the time,” said Birmingham Police Chief Jerry Tobin, who suggested that the killer might be seeing a psychiatrist. Tobin urged anyone in the medical or legal professions to come forward with any information.4 The police also began to suspect that the killer was being protected by someone close to him—a relative or a friend.

“NO INDIVIDUAL COULD HAVE KEPT FOUR CHILDREN FOR VARYING LENGTHS OF TIME WITHOUT SOMEONE KNOWING.”

BIRMINGHAM POLICE CHIEF JERRY TOBIN

It was probably because of that suspicion that family members of the victims were stonewalled by investigators. This was very frustrating to Tim’s parents, who had been especially cooperative in humoring investigators’ hunches early on. Detectives had believed that whoever was holding Tim hostage would react badly to his parents’ emotional pleas, so the couple had agreed to conceal their grief and keep their tone positive during news conferences. The Kings felt that they had received little cooperation from the authorities in return and subsequently sued the county prosecutor’s office, hoping to force it to release more evidence from the case. In 2012, the office did release 6,000 pages of case documents.

SUSPECT SPECULATION

Little official information meant that over the years, rumors have abounded over the identity of the Oakland County Child Killer. Was he a mysterious man named “John,” or a priest, or someone posing as a police officer? Few actual names were publicly tied to the case. Among the first was David Norberg, an autoworker who drove a car that looked similar to one described near Tim’s abduction site. Norberg had been suspected of killing two girls in the late 1970s, though he was not convicted. After he died in a car crash in 1981, his wife found a small silver cross inscribed with the name “Kristine.” She remembered the girl who had been the Oakland County Child Killer’s third victim and showed the cross to Kristine’s aunt, who said it was identical to one Kristine had worn at the Romeo Peach Festival shortly before her death.

Police exhumed Norberg’s body in 1999 to see if his DNA matched evidence from the case, but the results did not tie him to the murders. Some investigators say that there is no way that Norberg—a heavy drinker—would have been able to lure stranger-danger-conscious children into his car, and he has largely been dismissed as a suspect.

A convicted pedophile named Christopher Busch was on the shortlist for the King family and Erica McAvoy—Kristine’s half-sister. The son of a wealthy auto executive, Busch lived in the area at the time. He was questioned soon after Tim’s death and he admitted to investigators that he was a pedophile. He also drove a car that looked similar to one spotted at one of the abductions. Investigators wanted to keep him in jail, but L. Brooks Patterson—who headed the prosecutor’s office during the killings—released him as part of a plea deal. In November 1978, just a few months later, Busch killed himself in his home. A drawing of a screaming boy that resembled Mark Stebbins was reportedly found pinned to the wall.

DNA LINKS

Another suspect is James Gunnels, a 56-year-old man connected to Kristine’s murder through DNA evidence. In 2012, investigators revealed that a strand of hair found on Kristine was a mitochondrial match for Gunnels—meaning that it could have come from him or someone on his mother’s side of the family. Gunnels was no more than 16 when the crimes were committed, and he had been raped by Busch. In 2012, Gunnels met with the King family and insisted he knew nothing of the crimes.

In 2012, another tenuous DNA test produced a suspect named Arch Sloan, who was serving a life sentence for the rape of a 10-year-old boy in 1983. A hair found in his 1966 Pontiac Bonneville matched hair found at both Mark and Tim’s crime scenes. Although the hair was not Sloan’s, investigators believed it belonged to an acquaintance of his.

THE SEARCH FOR JUSTICE

While the King and Mihelich families zeroed in on Busch as a suspect, Mark Stebbins’ family filed a wrongful death lawsuit in 2007 against Theodore Lamborgine, a man who, like Sloan, was in prison for life on assault convictions. David A. Binkley, a lawyer representing the Stebbins family, said that his clients did not think Lamborgine acted alone and hoped the suit would help to uncover more information. He pointed to Lamborgine’s refusal to take a polygraph test despite being offered a massively reduced prison sentence if he answered questions about the Oakland County child killings. “Wouldn’t you deny being the Oakland County Child Killer?” Binkley said.5 Despite the family’s suspicions, the suit was dismissed in 2008, but the presiding judge left room for it to be refiled if more evidence should come to light.

Tim’s father, Barry King, has replayed time and again how he had talked to his son after the community learned of Kristine’s death. “All my kids remember me telling Tim, ‘If anyone tries to pick you up, drop everything and run and scream,’” he said. “Part of the tragedy to me is, once Tim got into the car, he knew what would happen. That’s the worst part of it all.”6 As long as the mystery of the Oakland County Child Killer remains unsolved, the Kings and the other victims’ families will remain haunted by the events of over 40 years ago, still searching for answers that always seem just out of reach.

LOCATIONS OF THE BODIES

Mark Stebbins: February 19, 1976

Mark Stebbins: February 19, 1976

Jill Robinson: December 26, 1976

Jill Robinson: December 26, 1976

Kristine Mihelich: January 22, 1977

Kristine Mihelich: January 22, 1977

Timothy King: March 22, 1977

Timothy King: March 22, 1977

CASE NOTES

Mark Stebbins: February 19, 1976

Mark Stebbins: February 19, 1976 Jill Robinson: December 26, 1976

Jill Robinson: December 26, 1976 Kristine Mihelich: January 22, 1977

Kristine Mihelich: January 22, 1977 Timothy King: March 22, 1977

Timothy King: March 22, 1977