121 North Bridge Street

Bellaire

231-498-2300

OWNERS: Joe Short and Leah Short

FLAGSHIP BEERS: Local’s Lager; Space Rock, a pale ale; Soft Parade, a golden beer made to appeal to wine drinkers containing toasted rye flakes and pureed strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries; Bellaire Brown; and Huma Lupa Licious, an American IPA

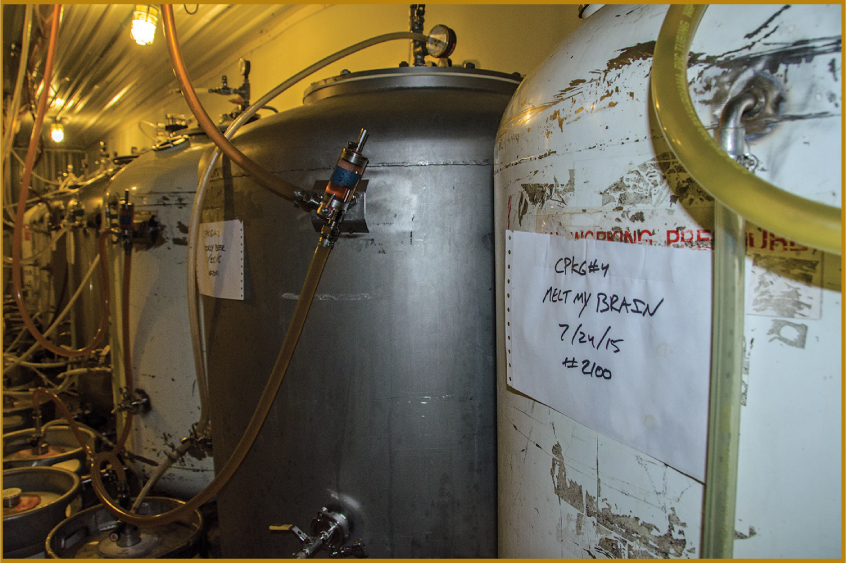

FERMENTATION TANKS AT SHORT’S BREWING COMPANY’S ELK RAPIDS PRODUCTION FACILITY.

Joe Short’s first brewhouse is in the basement of the Short’s Brewing Company’s pub in downtown Bellaire. Leave the noisy conversations and the clanking of glasses, plates, and silverware on the first floor and cautiously follow Short down the stairs of this one-hundred-year-old building. The rickety stairs creak under the weight of two adult men. With the first two steps it feels more like you’re entering the set of a horror movie than a place that’s hallowed among Michigan beer lovers.

But at the bottom of the stairs you can tell by the look on Short’s face that this basement brewery is a place he dearly loves. Here in this basement, between the stone walls and under the low, wooden-beamed ceiling, is where he and his brewers imagined some of the most unusual and honored beers ever made in Michigan.

There’s Bloody Beer, a light-bodied beer that glows red because it has been fermented with Roma tomatoes and spiced with dill, horseradish, peppercorns, and celery seed; it won a silver medal at the Great American Beer Festival (GABF) in 2009. There’s Key Lime Pie, a beer made with limes, milk, sugar, graham crackers, and marshmallow fluff; it took gold at the GABF in 2010 and 2014. Then there’s Melt My Brain, a golden ale that tastes like a gin and tonic cocktail. Melt My Brain is brewed with coriander, juniper berries, and limes that are blended with tonic water. It took a silver medal at the 2015 GABF.

Short leads a quick tour of the brewhouse. Wooden walls separate the brew kettles from the fermentation vats and a refrigeration unit that keeps the beer cold for the pub upstairs. Short knows every square inch of this cramped space: he designed it, helped build it, and has brewed hundreds of batches of beer here.

On one side of one of those wooden walls, a Peter Griffin doll—a character on the animated TV show Family Guy—hangs from the ceiling, overseeing the operations and providing spiritual guidance for the brewers. On the opposite side of the wall hang multiple medals Short’s Brewing Company has won over the years at brewing festivals and competitions. The medals are obscured by hoses, a tank of oxygen, and cleaning equipment.

Nothing better describes Short’s Brewing Company than the juxtaposition of the Peter Griffin doll lording it over the brew kettles while the awards hang forlornly to the side, seemingly forgotten. Griffin’s character is really nothing more than an overgrown child, and in many ways the brewers at Short’s are the same. The brewing equipment is their toy. Who cares about accolades when you’re having so much fun?

When a visitor points out the forgotten medals, Short shrugs. “That’s how we roll. We measure the success of our brewery by [the] size of our lines at beer festivals and not by how much bling we have on the wall.”

Even though Short’s Brewing is clearly a success, Short will tell you that he didn’t start his brewery to get rich; he did it because he and his employees love making beer. That attitude is the secret behind the success of Short’s Brewing Company. Short’s is the fourth-largest brewer in Michigan even though it did not distribute outside the state before 2016 as the other four in the top five did.

Besides distribution, there are two other key differences between Short’s and other Michigan breweries: the crew at Short’s cares what you think of their beer, but they brew more to their own personal tastes than what they think will sell, and they look at the Brewers Association style guidelines as rules for the other guys to follow.

Innovation isn’t at the heart of Short’s Brewing Company—quality beer is. But innovation is what Short’s is known for, and the best way to understand the ideas and philosophies behind Short’s beer is to hear his own words.

What’s the love affair with beer?

JS: Oh, man. It’s delicious. The brewing part is fascinating to me because it’s infinite.

What’s behind the explosion of interest in craft beer?

JS: I think it just comes down to excitement of so many different beers you can try and also to make. If you are a beer person, and a lot of us are, mostly just the excitement and rebirth—the renaissance of the handmade approach.

Joe Short, co-owner of Short’s Brewing Company, at his pub in Bellaire.

What is it that you do that makes you different from everybody else?

JS: We cover all the bases, so if you are looking for something more traditional or normal, we have it. If you are looking for something that’s going to blow your mind, we have it. I think that what makes us Short’s is we have a lot of spirit and energy behind what we do. We’re a really passionate group of people who really care about it. It’s not just a business plan that produces numbers. It’s something that we take more serious than anything else.

Does the beer reflect the tiny community of Bellaire at all?

JS: Yeah. In this community twelve years ago, craft beers weren’t really on the scene. So we had to make a variety to bridge the gap for people who were non–brew drinkers or people who were more traditional beer drinkers, and create a palate of stepping stones to more intense and unique and diverse craft flavors.

Why do you choose to be so different? You could be following the trend and brewing IPA like everybody else.

JS: We do brew IPAs.

Well, you get the idea …

JS: Yeah. I didn’t start Short’s to make a million dollars. I started Short’s because I love making beer. The reason why we do what we do is because we love making beer. And that’s what really fuels everything else. We’re getting a little more mature as a company now and have a lot of investment on the line to manage, but our heart is always behind what we are inspired to make. That’s why we take the approach that we take. Because brewing IPA all day is fun, but it’s not as exciting as making Key Lime Pie or making Bloody Beer—you know, where you get to use fresh herbs and spices and emulsify tomatoes or use marshmallow fluff or graham cracker. It’s something to get excited about between making production beers. It’s like, oh, I can’t wait for this one to come out. It’s going to be gooood.

What was the first beer you brewed as a company?

JS: I think it was Local’s Light. It was least expensive to make, so if I screwed it up, it wouldn’t hurt us too bad.

Where does your inspiration come from? Where do you get the idea to brew with spruce tips or pistachios?

JS: You know, different days, different times of years, different experiences. There might be an experience I have with food. Beer is really food, so … Lots of the beers that I design are inspired by foods. I love black licorice, so I wanted to see if I could design a beer that tastes like black licorice. I love Bloody Marys. I wanted to see if I could make a beer that tastes like a Bloody Mary. You know, pistachio and cream ale just sounds good. I think that was inspired by eating some Ben and Jerry’s pistachio ice cream. Other beers are inspired by ingredients that are available to us. So, like, maple syrup, for instance. It’s a local product. It’s fermentable. It tastes good. What else would that go with? Let’s see, pecans or walnuts.

It also comes from our staff members in a much similar capacity. Like [head brewer] Tony [Hansen] made the Cerveza de Julie, which is our version of Corona. He was down in Mexico on vacation drinking margaritas one year. Some of the beers are inspired just by other ingredients that we might have come across in beers that we decided not to make, so we end up with X amount of this product or X amount of that product—well, what can we make with that? What sounds good? It’s also being resourceful, too. And trying to figure out what else can top your last best creation.

Labels that will soon go on bottles are stored on a shelf at Short’s Brewing Company’s Elk Rapids production facility.

What beer are you most proud of?

JS: All the beers have their own DNA, so it’s just like a parent saying, “This is my favorite child.” No two children are the same. There’s stuff that you love about each one because they’re different. It’s like Spruce Pilsner—I love it because it’s a lager. I love it because it’s intense.

What’s the craziest thing you’ve ever brewed? What’s the most unusual thing you’ve ever thrown into a boil?

JS: The most unusual thing—that still didn’t work out, and I want to revisit it—is bacon. Real bacon. I know people who have used flavorings…. Animal fats just don’t work in beer.

I would say that one of the most successful weird beers was Key Lime Pie. That wasn’t my beer; that was Tony’s beer. But that beer has won multiple gold medals. Any of the imperial beers—any of our specialties are their own true works of art.

There’s a good deal of chemistry going on in the pot when something is boiling. There’s more going on during the fermentation process. How do you ensure that those unusual ingredients aren’t giving you a product that is undesirable or dangerous?

JS: I think that’s where the art form comes in. As a brewer you’re kind of like a chef in a way. You have to be smart about how and what you use and when you use it. Over time, we’ve developed certain practices that provide sterilization, and sterilization is the big key. Some wild fermentations are encouraged with other beer styles, but for us, depending on whether it’s a fermentable or something that can be dissolved in the wort, like honey or molasses, that stuff goes into the pre-fermentation side. If we’re using, like, an herb or something that’s more like a dry hop thing, then we do have to sterilize it because we don’t know necessarily where they might have come from.

But throwing in unusual ingredients like spruce tips—how much of those flavors comes through? I read about a guy in Minnesota who brewed a saison with invasive zebra mussel shells.

JS: Does anybody know what zebra mussels taste like, to start? Well, that’s just a cool concept, and I think that alone is going to sell the beer, but I don’t think anybody is going to drink it because they want to see what the flavor of zebra mussels taste like. I think that’s more an extreme marketing thing.

Brite tanks in the basement brewery at Short’s Brewing Company’s pub in Bellaire.

So, when does some unusual ingredient become something that legitimately gives beer flavor, and when does it become just a gimmick?

JS: Yeah, I guess that’s really up to the consumer. They say this is the age of variety. You can go to thousands of different breweries around the country and never have two beers that taste the same. It’s pretty awesome. And to think that people would want to throw a zebra mussel in there. It might provide a little dryness or bitterness, but you would never be able to pick it out of the lineup. I think the gimmicky stuff comes in when you start adding artificial flavors and you start cheating the natural process. Instead of using real strawberries you’re buying extract that tastes like Charms Lollipops instead. But I think the consumers can make that distinction.

I’m willing to bet you have a really thick notebook someplace with all the recipes you’ve brewed. How many recipes do you have?

JS: Yeah, [we have] almost four hundred different recipes.

What is the process of developing a new recipe? Who is involved?

JS: Mostly Tony, and there is a giant list that he will populate when people give an idea. And then we go through that list and decide what makes sense from a brewing standpoint, from a production standpoint, from a seasonal standpoint…. If there are certain spices we can only get certain times of year, certain fruits or vegetables we can only get certain times of year. Tony is the keeper of the schedule.

How many iterations do you have to go through to get the right flavor profile?

JS: We haven’t had anything that requires us to do anything smaller than seven barrels. Typically it’s [made on the system that’s in the basement of the pub], and 99 percent of the time we’re successful the first go. It may take a tweak the following year or the year after that, but for the most part it’s successful.

What are you tasting for when you are looking at the flavor profile of a beer?

JS: If it’s something like a specialty—for instance, Spruce Pilsner—we want the spruce to be in there. We would use the spruce like we would a hop. So, I guess it just depends on if we are tasting what we thought we expected it to be. Key Lime Pie, for instance, we don’t want it to be too bitter. We want it to have a soft mouth feel. We want it to touch on that graham cracker and that lime and that meringue. But we also still want it to taste like beer. I guess that’s when we know.

Strawberry Short’s Cake was a very interesting and relatively simple beer to develop. It was like, choose the right malts to make a cake flavor, add enough lactose to make the body full. And the strawberries are noticeable but not overpowering and it also still tastes like beer.

What attracted you to this business? Let’s face it, this is not the easiest business in the world. It’s capital intensive, it’s long hours …

JS: Well, I’ve never been afraid of long hours. I’ve always gotten a lot of satisfaction from working hard and producing something that I care about. I started in the hospitality industry at a young age; I grew up working in restaurants, so that helps supply that side of the pub. When I first started making beer, it was just such a fascinating thing for me. It was a challenge to not only brew something good, but something that was outstanding. And I loved that challenge and I loved the reward of being successful at the challenge. Just like anything else, you want to repeat that process and that feeling over and over. It’s like getting a sweet golf shot; you want to keep going back and getting that one sweet hit that you got. The more that you got, the more rewarded you felt. So it’s a very fulfilling career for me.

Are there any beers that you’ve rejected for being too weird?

JS: Not really, but we haven’t made a lot of them yet, either—there’s still a lot on the list.

So you have a huge list of beers someplace that you want to brew.

JS: Yeah, I’ve got a home brew system at home that I haven’t used yet, but I’ve got a few that are going to be very specific to that system before we hit the pub batch with it. I just need to find the time; that’s the hottest commodity going right now.

In most breweries, medals won at the Great American Beer Festival are proudly displayed in public. At Short’s Brewing Company’s brewpub in Bellaire, the medals hang on the wall of the basement brewhouse, as if they were no big deal.

ONE MORE THING: Joe Short admits that he’s never done things the easy way.

Short’s Brewery now occupies six straight storefronts on a stretch of M-88 in downtown Bellaire. There’s a 350-seat restaurant and a store for Short’s swag. The brewery’s corporate offices are across the street from the brewpub in an old bank. And there’s a production facility in nearby Elk Rapids.

Looking back, Joe knows he never would have gotten this far without his wife, Leah, and he credits her with saving the business. “We were so blindly ambitious that we were dysfunctional,” Short says. That was when Leah stepped in and took control of the restaurant and the checkbook. That move allowed Joe to focus on making beer, fixing things in the new brewery’s old building, and expanding to the Elk Rapids facility.

And just when life seemed as difficult as it could possibly be for Joe and Leah, they made yet another decision to expand—they decided to start having children. Oh, and they did one more thing a sane person would view as just plain crazy—they bought a puppy.