20

Prayers and Providence

IT HAD BEEN A HOT AND SWEATY NIGHT for Xanthia, despite the cool desert air. Alexander had spent all night wiping her face with a cold cloth soaked in spring water. He had been praying as well, as he had never prayed before.

It was nearly dawn when Xanthia’s fever broke. “Who stuck a hot iron in my ankle?” she groaned, her eyes still closed.

“Not me,” said Alexander with relief. “I’m going to keep this cloth on the spot so the swelling will go down.”

“I’m so thirsty,” said Xanthia as she struggled to open her eyes. “I could drink a whole jar of water.”

Alexander went down to the nearby spring, carrying a skin to retrieve the water. He felt almost faint with relief that Xanthia seemed to be coming around. But how soon would she be able to walk on that ankle? That was another question. Alexander was afraid that their money, most of which had already been devoted to buying spices, would soon run out.

The spring was some distance away, but Alexander got there as quick as he could. He slowed down as he bent down toward the sweet, fresh water. He was beginning to allow himself once more to think ahead to a day when he and Xanthia could be together. The funny thing about being a slave was that, since there were no arranged marriages for slaves, they were free to woo whomever they found suitable, usually someone in the same household. Once set free, they could marry and could even continue to work in the same household. Many slaves, in fact, preferred to continue in the same household even long after they were manumitted. It offered job security and the comfort of a familiar environment. Of course, all this depended on one’s master—but Alexander had no doubts about Hector.

By the time Alexander returned to Xanthia, she was sitting up and peeling an orange. He paused to admire her face—intelligent in its dusky beauty—and her graceful figure. He loved everything about her—her voice, her mannerisms, her storytelling, her hard work. All this was undergirded by her deep faith in Jesus. He longed to have more of her faith, a faith that had gotten her through many hard times and crises.

But Alexander could not comprehend how Xanthia received the prophecies she occasionally shared in the worship. When asked, she always answered, “It comes from out of nowhere, from G-d alone. It’s not something I think up in advance. I simply hear it and repeat it. I am just the vessel. A woman can’t refuse to give birth when she is in labor, and I can’t resist the impulse to share the message.”

Xanthia looked up as Alexander approached. “I see you are recovering your appetite,” Alexander said.

“Yes, but I’m not ready to travel yet. Later today I want to try to walk a bit, when the swelling has gone down. Maybe I could even ride the donkey a bit on our way home. But right now I need that water!”

Another Side of Slavery

There is no question that slavery is an iniquitous institution, both in antiquity and more recently. Jews especially realized this and sought ways to ameliorate its effects, especially in their own communities, and this trend continued with Jewish Christians in their own communities.

But slavery in the Greco-Roman world was different from antebellum slavery in the old American South. It was not based on race or class. More than anything else, it had to do with who was and wasn’t a conquered people. For example, many Jews who dwelt in the Promised Land were shipped to elsewhere in the empire to work after AD 70. There is no doubt about it—slavery was not preferable to freedom, even ancient slavery. But suppose the choice was between freedom with destitution, or slavery? Many ancient persons chose the latter in a heartbeat, and this was not just another example of preferring a familiar hell to an unknown heaven. Sometimes life in servitude could be better than just endurable or tolerable; it could actually have its good points. For one thing, if you had a good master, you could have long-term job security.

Slaves worked in all sorts of professions in antiquity. They were not just agricultural or domestic workers. In fact, a good deal of the Roman civil service was composed of slaves. By some estimates, 50 percent of the population of the empire’s major cities were slaves. Slaves were businessmen, actors, teachers, artists, musicians, carpenters, stone masons, business managers, and so on. Slaves were not confined to menial tasks in the empire, though it is true they also did do the jobs others did not want to do, such as working in the mines—the most dangerous job.

So it’s not altogether surprising that a slave would want an epitaph like “Slavery was never unkind to me.” There were apparently enough benefits and opportunities to prevent much revolutionary fervor among slaves. Revolts, such as the Jewish revolt, were not led by slaves. Indeed, no ancient government, not even a Jewish one, sought to abolish slavery. No former slaves, even those who were literate and able writers, attacked the institution in writing after they obtained their freedom. They did write against the abuses of slaves and slavery, but that was all.

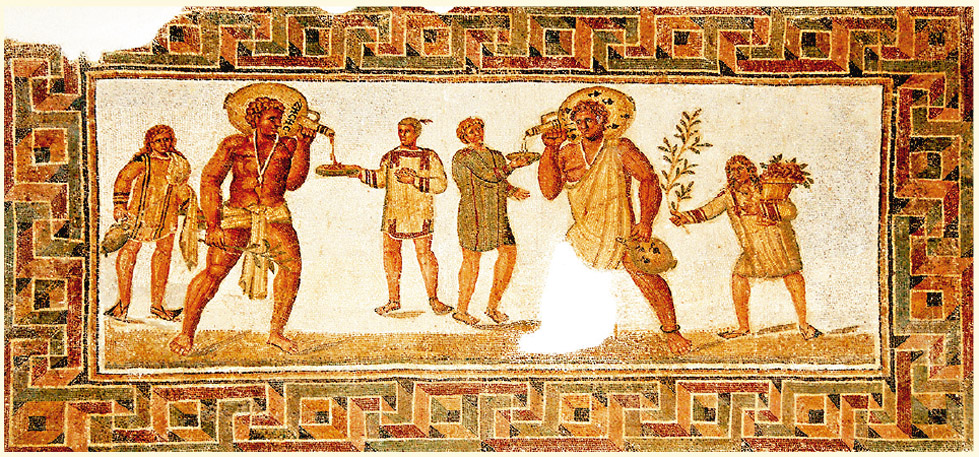

Figure 20.1. Mosaic depicting slaves serving at a banquet, from Dougga, Tunisia (third century)

While it may seem hard to fathom to us, one of the advantages to being a slave is that once you were manumitted you instantly became a Roman citizen, taking part of your master’s name as your own. You went from being legal property to having the highest citizenship status in the empire. This was no small thing, and the stories of manumission are numerous and varied. It happened with great regularity.

There is much more to be said about ancient slavery, and more to be said against it as well.a This is not an attempt to justify or praise it. But it is important to see it in a more balanced light than is often the case today. Otherwise we will have a hard time understanding the frequent use of slavery metaphors to talk about positive roles in God’s kingdom, the role of Christ when he came to earth (Phil 2:5-11), and even as a form of salvation, which rescued people from death and destitution.b

aSee Ben Witherington III, Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 229-30.b

bA much fuller version of this sidebar can be found in my commentary The Letters to Philemon, Colossians, and Ephesians (Grand Rapids; Eerdmans, 2007). On the use of slavery language in a redemptive way, see D. B. Martin, Slavery as Salvation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990).

Alexander broke his admiring gaze and handed her the dripping skin of water, blushing. “Sorry. Here it is. It’s just such a relief to see you getting better.” In fact, he felt that life in general was going to improve soon. But for now, they were stuck in Petra for at least one more day. He couldn’t really mind too much, though, as long as they were together. His heart warmed, and he offered a brief prayer of thanks to the Lord, finishing it with a silent request for guidance.

Hannibal had returned to Julius’s office in the basilica in the town center of Pella. It would be an understatement to say that Julius was not happy with his news. Smashing his hand down on his little desk, he bellowed, “What? You mean to tell me that slave girl has vanished?”

“Not exactly vanished, my lord, just left town. And for some time. I hesitate to tell you, but I also spoke with Hector’s lawyer Zeno this morning. He asked me to tell you that you would be hearing from him before long.”

Julius groaned and turned away. He considered his options, knowing he had better step carefully. After all, he was the new judge in town and needed to be making friends, not enemies. The town was mostly Greeks and Jews, not Romans, so he had few automatic allies. He wasn’t sure right then what he would tell his superiors about the slave girl—but he knew he would think of something. He always did.

With Hannibal’s hulk still overshadowing his desk, Julius said, “Thank you, Hannibal. You may go on home now.”

“My lord.”

It was going to be another tedious day in court, dealing with the annoying trials and travails of petty suits. How exactly, mused Julius, had he allowed himself to be persuaded to come and work in this godforsaken town of Pella?