6

Levi’s Flight

LEVI WAS BEYOND FATIGUED. Every joint was stiff, every muscle sore. He had become closely acquainted with every feature of the cistern—now mostly dry—behind his house on Mount Zion. It was the evening of the third day after the sack of Jerusalem, and Levi had already drunk what little potable water had been in the cistern. This cramped silo had saved his life, but the noises, smells, and general chaos above had frayed his nerves and preyed on his mind.

For years Levi had lived on Zion. And while he continued to frequent the temple, he also participated in the increasingly secret gatherings of followers of the Master. When Jacob, the brother of Jesus, had been martyred some eight years earlier, some feared the Jerusalem assembly would disappear. But it had not, in part because some of the original disciples of Jesus stayed in Jerusalem despite opposition. But now, with these traumatic events, it seemed that Jerusalem was not going to survive as a religious home for anyone. Three days in the cistern had hardened Levi’s resolve to gather up his few belongings and flee the shambles of the holy city.

Levi had had many hours to think over the events of recent years, as well as his own fate. He thought back to the last days of Jacob’s life.1 Levi, being a tax collector, but of priestly lineage, was disgusted with the whole line of Caiphas and Ananus, a family that for over thirty years had provided the high priests for Jerusalem. This same family had conspired to have Jesus killed.

Now it was Ananus’s son, also named Ananus, a proud man of violent temper, who had seized the office of high priest. He had used the time between Festus’s death and the arrival of Albinus, the new procurator of Judea, to take matters into his own hands. He went after Jacob, the head of the Jerusalem church, as well as some other Jerusalem followers of Jesus. Jacob had been dragged before the Sanhedrin, accused of breaking the Torah, and stoned.2 Later, when Albinus had read the letter of protest from righteous Jews who condemned this unjust action, Ananus was removed and replaced as high priest. Levi had been the scribe who composed the letter. Jacob had been buried near the spot where he had been martyred, and they had erected a grave stele there. Levi wondered whether it had survived the onslaught on the city.3

Sitting at the bottom of the cistern, Levi had wryly recollected the story of the prophet Jeremiah being imprisoned in a cistern before Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians. I may not be a Jeremiah, he thought, but Jerusalem is replaying its tragedy. Levi knew he had to flee the city. But how?

Like the Master, Levi had never married. This path came with its burdens, but he had focused his life on his tax collecting as well as on scribal work. For years he had thought about how he might write an account of Jesus. By habit he was a man with scrolls and parchments on his mind, and as the present disaster descended on Jerusalem, he had thought to visit and persuade John Mark’s mother to entrust to him a copy of Mark’s story of the good news of Jesus. It was a treasured account, based on Peter’s preaching, and copies must be preserved. Levi was deeply familiar with it and continued to ponder how he might use it as a template for his own account. There was so much more to tell, but Mark’s sprightly paced account would contribute much to what Levi wished to narrate, including Jesus’ birth.

Levi decided he must do something, now. He began his ascent of the cistern wall. Each move was choreographed from practice. A handhold here, a secure foot placement there, a tricky reach and an awkward clambering over the lip of the pit, and he was out. His wiry old frame hurt from top to bottom, but he was whole. Under the cover of darkness he would try to get out of town. He knew a back way from Mount Zion to the Jericho road, and he thought he must take his chances on it. He prayed that the Roman troops would have grown tired of pillaging by now. Anyway, night was now approaching, so hopefully they would be feasting and sorting their booty. The mess they had created would take months to sort out.4 The Romans still had to rule the province, and Levi knew they did not like messes.

First-Century Houses

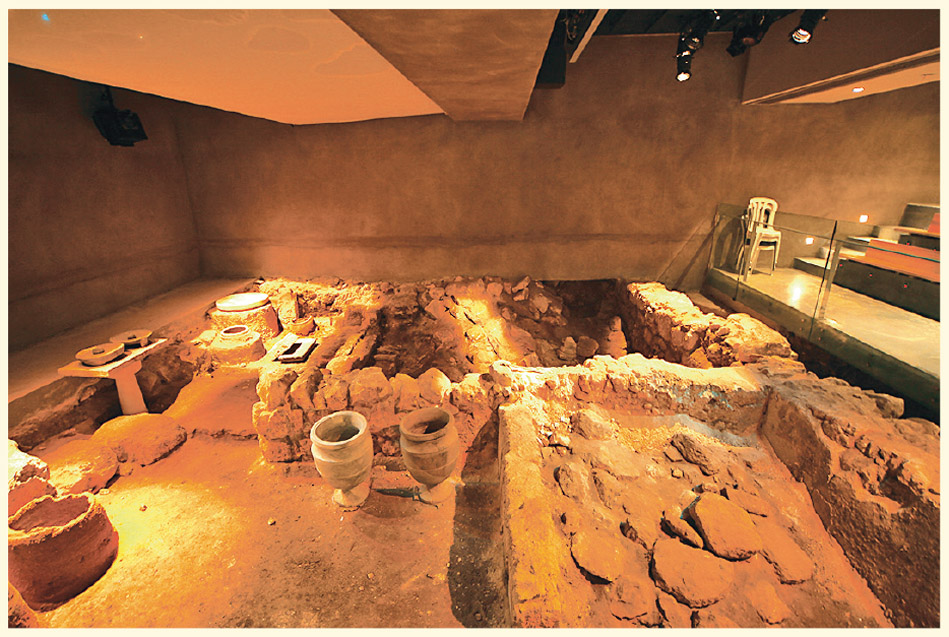

Quite a few first-century Jerusalem houses have now been excavated, and these can be compared with ones excavated at Capernaum as well. The results are similar. Most homes, even a larger one like the so-called Burnt House in Jerusalem, had only a few rooms or partitioned spaces, and they were quite small. There was a living area that included the cooking area near the door, as these houses did not have chimneys and in some cases did not have windows either. If the house was large enough, there was a guest room for extended family or visitors, and one major bedroom area (the family slept together, parents and children). Sometimes there was a partition in the back portion of the house, behind which would be kept a beast of burden to prevent it from being stolen.

In Luke’s birth narrative story of Jesus (Lk 2:7) it is said that the baby was placed in a manger because there was no guest room available to them. This likely means that Jesus was born in the back of the house (probably of relatives) rather than in the guest room, because that room was already filled with guests (perhaps relatives from afar who had also come to register for the census).

Figure 6.1. Remains of a first-century house interior in Jerusalem

Figure 6.2. Remains of first-century houses in Capernaum

An emaciated cock scurried underfoot, startling Levi. “How did you escape the stew pot for this long?” he wondered aloud—but then he remembered that this cock usually hid under his house to avoid the August heat.

Levi reached to open the door of his little house. His father, Alphaeus, had left it to him. His father had been in the regular priestly rota that served in the temple, and he had bought this little place a long time ago so he would have somewhere to stay when he came from Galilee to Jerusalem. It was not much, but conveniently located.

In the dimming light Levi grabbed a leather traveling bag and began filling it with the essentials he could afford to carry. His writing implements he put in a small metal case and then dropped them in the bag. Despite his weariness and hunger, his mind felt clear and sharp. He had rehearsed everything in the belly of the cistern. Carefully he extracted the scroll of Mark’s good news from its hiding place and slipped it into his leather bag, along with one other papyrus scroll.

To distract himself, Levi mulled over his plans to make his way to Capernaum via the long way, the King’s Highway, across the Jordan. It seemed a prudent route. Would it be the last time he would ever see Jerusalem? Would the temple ever be restored? Reason told him it was unlikely. His heart hoped he was wrong.

Tax Collecting in Jesus’ World

Tax collecting in antiquity did not work the same way it does today in America or Europe. “Tax farming” was the normal practice. The governing officials contracted with private individuals to do the tax collecting for them, going house to house and estate to estate. The agreements could vary, but in Galilee it seems the governing official would set an amount of tax he expected the tax collector to provide him, with any additional amount being the tax collector’s cut. This practice led to all kinds of corruption and gouging, and it was another reason why the Jewish populace despised tax collectors and lumped them together with sinners and traitors. We might imagine the animus was especially strong in Judea because the tax money was going directly to a Roman procurator, who was not a Jew at all (unlike the Herods, who at least had some Jewish blood in their lineage, though they were mostly Idumeans).

Figure 6.3. Both sides of a Roman coin (circa 225-212 BC)

In addition to collecting taxes on land and possessions, there was toll collecting in border regions. When a person crossed the border, say from the territory of Herod Philip to the territory of Herod Antipas, they had to pay a toll. Finally, there were temple taxes. Jews were expected to pay money into the temple treasury as part of their service to God, money that in part went to the maintenance and upkeep of the temple. It appears to have been a new practice in Jesus’ day to have moneychangers, in addition to sellers of animals, within the outer court of the Jerusalem temple precincts. The Tyrian shekel or half-shekel was the coin used to pay the temple tax in Jerusalem. Even though it had on it an image of a pagan demigod (Herakles/Hercules) and an eagle, a symbol of pagan power, it was made of the purest silver, and for the temple authorities that consideration overrode its pagan imagery. Thus the moneychangers offered the service of exchanging ordinary coins for the Tyrian shekel in order to pay the tax.

Rustling through a bag of items, he located his seal. Granted to him by the administration of Herod Antipas, the seal symbolized his authority to collect taxes in Galilee. He hoped it would still earn him some small status with any Roman authorities he might encounter, since Herod had been a client king of Roma. Surely any official of Herod would be assumed to be an ally of Titus and his efforts to subdue rebels. Of course, Levi had not been collecting taxes for Herod for many years. But Roman soldiers would not know this. Levi was banking on it giving him some immunity against being abused or taken prisoner.

The sun had now descended over the western edge of the holy city, and in the twilight Levi picked his way along. He would be heading northeast, down the Jericho road. It was a regular commuter route for priests and Levites. Many of them could not afford to live on Mount Zion and thus lived in Jericho, commuting back and forth as the rota called them to duty in the temple. He hoped for some traffic he could blend in with.

As Levi reached the last vista of the city on the Jericho road, he paused and looked back at the darkening profile of the city. Throat tightening, he whispered, “Farewell, once-great city.” All the obedience to Torah, all the sacrifices, all the prayers . . . what did any of that mean now? What had it accomplished, if this was the city’s end?

Even at this hour there were old men and young men, old women and young women, small children and infants, traveling down the road. The way through the wilderness was moving in the wrong direction. Instead of fleeing Egypt, God’s people were fleeing their own capital city! The dust kicked up by the refugees hung in the evening air; the sounds of sandals, hooves, and wheels were accented by coughs and wheezes. Where would they all go? Where would they sleep tonight, if they did? Levi pulled the edge of his cloak over his mouth and joined the traffic.

Levi planned to keep going all the way to Jericho this very night. The journey of about seventeen miles was almost entirely downhill, and with this many people traveling, dangers from bandits and thieves were minimized. But the thirty-two-hundred-foot descent from Jerusalem to Jericho would take its toll. Three days in a cistern had depleted his energy reserves.

It took him six hours to make the descent to Jericho, and even by the second hour his anxiety had slackened. While he did not see anyone he knew among his fellow travelers, their presence was reassuring. As he approach Jericho, the moon was shining high in the sky, as it was well into the evening, perhaps even midnight. He began to wonder where he might stay for the night. In happier days the famous inn at Jericho would have been an option, but with the flood of refugees entering Jericho, it was out of consideration.5

Levi knew where most of the priests lived: on the far side of the city, near the creek bed. He decided to try there first, appealing to his priestly lineage. As he passed an ancient sycamore tree, he recalled that Zaccheus, another tax collector, had once lived in this town. He and his family had become followers of Jesus. That was more than forty years in the past—but still, Levi’s memory fetched up a general recollection of where they had lived. He would try to find their house first.

Rummaging through his bag, he pulled out his little hand lamp and a stoppered vial of oil. Stopping by a brazier where some travelers had been warming their hands in the chilly evening air, he lit the wick. With his lit hand lamp in one hand and his bag over his opposite shoulder, Levi made his way to the neighborhood and, after some wrong turns and backtracking, found a familiar-looking home. Taking confidence in the faint image of a fish on the door, illuminated by his flickering lamp, he knocked. After a minute or two, the door cracked open partway, and the voice of an elderly woman whispered, “Who is there?”

“It is Levi, a follower of the Master. Have you a floor for me to sleep in safety tonight?”

The door opened wider, and suddenly there was a blaze of light from a hanging collection of lamps in the center of the room. Blinking hard to see, Levi found standing there to greet him the stooped figures of Zaccheus and his wife. Levi stepped into the house and pulled back his hood so they could see his face clearly. Only then did he realize that his hand was paining him from hours of holding a death grip on his bag—but it was worth it to protect the scroll inside with Mark’s story.