Spring, Karoola

Let no man say, and say it to your shame,

That all was beauty here until you came.

Couplet commonly found in parks around the world

Now that Wilf’s garden was cleared, the light was making surprising things grow. A small oak tree seemed to have seeded itself (I recognised its distinctive leaf from Susan’s garden) and a row of glossy green-leaved shrubs that I didn’t recall being there last year had appeared at the top of the higgledy-piggledy dry-stone wall. Audrey had tried to remember the name and thought they began with A, so we went through one of the Stirling Macoboys and found them: Acanthus mollis or oyster plant. I never got the chance to find out what Wilf had in mind for the part of the garden he’d reserved, but at least it was less dishevelled now and, if he was anywhere, maybe he would make things grow the way he wanted them. Barney helped me to plant two boxes of daffodil bulbs we’d rescued from an old vineyard garden being demolished in Pipers River. And with Wilf’s garden gnomes dotted underneath the trees I hoped he might feel more at home.

Aside from gardening, I visited Audrey for home-cooked suppers that usually involved sherry poured from a decanter and sipped from a certain glass. Ma, who would soon be eighty, was accustomed to living on her own and fending for herself, so meals tended to be on a tray for one. Every now and then, when she knew you might be visiting, she’d bring out one of her standards, a simple recipe cooked from her black-covered bible, The Good Housekeeping Cookbook, published in 1950. She’d taught herself to cook from it before she was married and now it was falling apart at the seams. ‘Oh, this old thing,’ she’d say, irritated at its stray pages that had come unstitched. But the precious black book still came out. I don’t think Audrey ever approached cooking as a pleasure in itself. I imagined that as for many stay-at-home wives and mothers, it was more something she knew she had to do. I admired how she still made the effort to cook, although really, she couldn’t be fussed.

I wasn’t sure I would have got to know Audrey like this if I’d stayed in London. Whenever I visited from the UK we seemed to get under each other’s skin. I think it was because I couldn’t relax in her company, and I would return to London feeling guilty and relieved in equal measure. When you’re consciously trying to parent yourself, a parent still parenting is suffocating. Whatever it was, we ironed it out and we had made it to friendship. I could sit with her in the middle of the day watching Ellen on the TV turned up way too loud, her cigarette smoke clouding the air, and not want to leave immediately. We’d come a long way.

One day I came home from Audrey’s to find a jar of fresh blackberries on the front doorstep. It was a recycled jar, stuffed with plump fruit, sat on a berry-patterned napkin in the middle of the top step. There was no card but I knew it was a hello from my friend Rose and the wilder boundaries of her garden. Nothing tricked up or fancy, just an expression of friendship in a jar. I unscrewed the lid and popped the first berry into my mouth, savouring it. The rest I’d save for an apple and blackberry tart, already imagining the swirl of dark liquid as it seeped into the apple amid dollops of thickened cream. I loved how, with a little thought, someone else’s surplus could become a precious gift. And, just like the peace and beauty I aimed to preserve at the Nuns’ House, I never wanted to take the generosity of others for granted, and returned Rose’s offering with a tart.

The local tip opened on Sundays at 11 am but Malcolm usually got there at ten so I headed off early with some garden rubbish not destined for the compost. Sure enough, there he was, organising the old washing machines and sheets of corrugated iron. He said he liked to arrive early so he could get things ‘cleaned up’ before the rush. For Malcolm, there was a place for everything, and everything in its place: old farm equipment and water tanks, furniture and bicycles, a bin for cardboard boxes, another for vegetation, and a total of eight numbered skips. Rubbish disposal cost two dollars per trailer and it was one dollar per carload, until the council increased its pricing, much to the dismay of the locals.

A small hut sat just inside the tip entrance. At first sight, it looked like a lean-to, done up for a tip man to while away a chilly day undercover. A frayed armchair appeared welcoming in one corner, a bookcase with magazines lined the back wall, and there was a heater for cold winter days. Malcolm’s self-styled retreat was actually a tip shop, and everything was for sale.

‘How much for this old putter?’ I asked.

‘Two dollars.’

‘The vase?’

‘Two dollars.’

‘What about this old oil can—isn’t it sweet?’

‘That’ll be two dollars,’ Malcolm said with a smile.

Libby arrived and, joining me in the fossicking, spotted some shapely wooden-handled leather-making tools. We chatted and agreed that sometimes the tip seemed more sociable than the village green: both rubbish and gossip got recycled here. I liked that there was a place for unwanted things to go where they might again be wanted, rescued from oblivion and restored by love and attention. With a little dust, a good wipe, a smear of O’Cedar and a place to live or a purpose, most things destined for the skip could be brought back to life. I noticed that things seemed to revive in direct response to the amount of attention received; that is, if you valued something, it would be valuable. This was different to putting a price on something. Things that had charm and were valued were priceless—valued in and of themselves. Because they meant something, they had worth. Because they were appreciated, they glowed. I thought this was something financial markets rarely understood and industry only ever regarded in extremes, either to plunder or ignore, like the tree farms that were now encroaching on Pipers River Road.

In four years, I’d witnessed much of the length of the road from the Nuns’ House to the coast turn from pasture to plantation, and an improbably large pulp mill had been approved not far from here: up the valley a few kilometres, west across the Tippogoree Hills on the banks of the Tamar River. Many people in the local community had campaigned against it because of concerns about pollution. But that didn’t stop the forest industry march, where uniform rows of non-native gums replaced native bush, scrub and farmland. Wildlife scattered, and so, too, did families who left for the city, the Western Australian mines, or the retirement belts of Queensland and elsewhere. I couldn’t understand why Tasmanian native trees, like blackwood, myrtle and sassafras, weren’t being farmed instead.

I understood the need for jobs, for paper from pulp and for timber for building, but when farmland changed so rapidly into plantations, and all you could see from the roadside, for kilometres, was one kind of tree, who would draw the line, and where? Who would say when enough was enough? I couldn’t help but wonder if all the farmers in the valley decided to sell their land to forestry, and thousands of one species of tree were planted, how would it feel living here at the Nuns’ House then? Could lemon trees be tainted by spray? Would the groundwater be affected? How would I know? Would there be a chain of log trucks on Pipers River Road, and how safe would Audrey be driving the bends to see me then? When I had spent this time to craft a life, could it all be lost?

My dream to save Coronation Hall and turn it into the Pipers River Produce Hall, home base for a new food magazine and local market, was just that. Leigh and I had managed to save the hall from demolition . . . for just a few weeks, until the council caught up with its paperwork and the deed was done. Even though we’d convinced the local aldermen of the possibility of new uses, we had been unable to secure the funds to save it from the bulldozer. I guess I knew it would happen one day. But the day came sooner than I thought.

I was rostered to work at Jansz and took the shortcut to the vineyard as usual, turning into School Road and up the lane I had given avenue status because of how gloriously it was hedged, only to see that the hall had vanished completely. All that was left was a finely gravelled area where the building once stood. I pulled over onto the hard shoulder and sighed. There was no sign or plaque. Nothing to remind future generations of the times spent here at Coronation Hall, Pipers River. Its past was gone now, abolished by the council. And the private memories of birthdays, anniversaries, badminton tournaments, dances, celebrations and commemorations, of families coming together to share stories and the joys and tears and first kisses of their lives over seventy years, had been publicly erased, extinguished and then raked over carefully to delete any sign of their history. It was as if nothing at all had ever happened there; not even a shadow remained.

The disappearance of Coronation Hall made Barney and me even more determined to save what we could, when we could. One day, Barn had just finished his Lilydale school bus run; from the sunroom I saw him pulling into the driveway. He was excited because he’d spotted a massive pile of wood in the local sawmilling yard in Lilydale where he parked the school bus. There were some good-looking old timbers, sleepers, floorboards. The sawmill owner had said it was okay to take what we wanted from the burn pile.

‘Come on, let’s go,’ said Barn, ‘before it’s too late.’

We both shared a passion to save, fix, mend, not spend. I only had time to grab gloves and hop in the ute next to Barn, while Harry was tied up on his lead in the back. The bonfire was the size of half a house. Hidden within it were sturdy old bridge timbers and massive beams that needed two to carry. We fossicked and lurked among the pile like wily old scavengers, selecting lengths we thought were salvageable. Barney tied down the ute load while I faffed around with ropes I could never remember how to knot. I was such a girl about this and, because Barn could always do it better and faster, it remained that way, although he often took time out to show me with no sign of irritation.

It wasn’t hard to think what we could do with some of the wood. Ever since arriving here my books had been piled up in rows along the Nuns’ House hall and corridor. Every time I tried to look for a particular book the Lego-like towers threatened to topple. I laughed when I saw photos of similar piles in posh interior design magazines, because people who have book towers could not possibly get to read them.

I had long held plans for a library. My brother Martin had suggested floating a bookshelf island from the ceiling. I liked the idea but it seemed too fancy for the Nuns’ House. Les had done some research through his Tasmanian ‘woodie friends’: brilliant men who crafted wood with their hands. But the price was outside my budget. Meanwhile, bookshelves in secondhand shops seemed to be a dying breed.

Between us, it just sort of came together. We built the library from some of the timbers we’d salvaged, along with some old floorboards and bridge timbers that Barn had kept stored and dried underneath his house.

I chose as my library a nondescript spare room the nuns had once used as their chapel and we set to work, turning one whole wall from top to bottom into bookshelves. We worked well together, planing and sanding, sawing and bolting; sturdy floorboards were turned into shelves and handsome beams into uprights. It was hard work, measuring and fitting, without a plan, on a wonky wall, but after several days we finally stepped back and toasted the magnificent Nuns’ House Library, made out of wood salvaged from a bridge. A home fit for books that had travelled around the world and back—twice. To reach the top shelves I found an old stepladder in a salvage yard which I spray-painted gold. Next, I dusted down the shelves and started unstacking the piles, revelling in finding a place for each book. Feminist texts went straight to the top shelf, while books about gardening, writers, photographers and Tasmania got prime space. While I sorted through them, some books spoke to me, seemed to have their own perfume, even enticed me to stop what I was doing and open them, only to find a name or year I could not remember writing inscribed on the title page, or revelations offered up from the past.

Wilf cherished his library, and after he died some of his books came to me. One, Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, had Wilf’s signature scrawled on the inside along with the date, 1971. It was a volume he used to quote from throughout our childhood and it smelled of old bookshelves, dust and tobacco. I was hungry to find one verse in particular about a moving finger . . . I turned the pages one by one, scanned left to right . . . there they were, the verse and my father’s words like Lazarus on the page:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ, Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

Although he quoted it all the time, as children I don’t think we really understood it, except we liked how it sounded profound. Hidden between two pages I found a piece of lined notepaper. It was stained with a coffee ring and scrawled in his doctor’s handwriting: ‘Democracy—A political system calculated to make the intelligent minority subject to the will of the stupid.’ Ha, that was Wilf all over. Disdain for the ways of the world without the power, he thought, to influence it. I loved how his mind had touched the page of a book I could hold in my hands after he’d gone.

Our passion to repair and reuse found other outlets. On the hill behind the Nuns’ House the outlook of the white weatherboard Sacred Heart Church was paramount. The church, completed in 1898, had a separate belltower and I’d always admired the big brass bell with its very own roof made of red corrugated iron—more agricultural than ecclesiastical. Even though services were held here every fortnight, I’d never heard the bell ring. In fact, the bell rope was missing. Between us we conspired to replace it. One evening, under cover of dark, we walked more briskly than usual up to the church. Barney pulled on his black ‘ninja’ gardening gloves and, while I kept watch below, climbed the tower like a monkey, attaching a length of rope to the old bell so that it could be rung out again across the valley. That night, we each took turns to ring the bell and decided we should walk up to the church every full moon to ring it out loud. Sadly, we learned that the church secretary had received a complaint from a neighbour about the bell pulling, so we stopped. However, a few weeks later our hearts lifted when we heard the bell being rung on Sunday morning for the 9 am service. Apparently it hadn’t happened for years.

Every now and then, depending on how brave we were feeling, we’d stroll up to the church and give the bell rope a short tug. One evening, Dave Flynn followed us up the hill in his ute, we guessed on his council rounds. We stopped and chatted, and during the conversation he pointed to a massive gum tree and recalled playing in its tentacle-like branches as a child. Maybe it was the nostalgia in the air, the conversation, or the rogue in Barney, but he was the one who started it. We each took turns, pulled the rope and sounded the bell out over the neighbours’ roofs, across the fields and down the valley. I think Dave might have smiled on the outside that day.

Some days it was harder to write than others. Interruptions stopped the flow or the concentration. Harry would visit, or Barn might drop in on his way somewhere for a hug or a catchup. I would take a break to make three coffees in a row, but still no words would end up on the page. There were other distractions— like how to earn a living while I wrote. I wanted to remain creative and self-employed and not have to work full-time. So freelancing suited me, but I despaired a little when jobs were cancelled: three weeks’ work at the radio, two days at cellar door, a commission to write a feature for an American magazine about a dairy on King Island . . . all cancelled for varying reasons outside of my control. I went for a stroll to see the garden still growing. The planets may not be lining up for me, I thought, but they are aligned. The silver birches were growing nearly a metre a season and my blueberry circle was slow but promising. The newly planted olive tree had definitely found its feet, the veranda’s climbing rose had recovered because I’d learned how to prune it, while Les’s echium seeds had taken and were now as tall and phallic as he had imagined them to be at the Nuns’ House.

One day, Barn dropped in with a passenger he wanted me to meet. It was Billee, Dave Flynn’s sister. He was giving her a lift into Lilydale to pick up her car that was being serviced. As a thank you Billee had made him two cakes. He favoured the cream sponge—all sweet, eggy and puffy—and I asked Billee if she’d mind sharing her recipe. She said she’d made it once a week for most of her life.

I later found Billee’s recipe in the Centenary Cookbook, a collection of country recipes from the women of the Karoola-Lilydale Parish, compiled for the centenary of Karoola Sacred Heart Church (1898–1998) and kept in the State Reference Library. There was Mary East’s Queen Mother’s Cake, Heidi Robnik’s Guinness Loaves and five recipes for sponge cakes alone, all with different combinations of eggs, cornflour, cream of tartar, bicarbonate of soda, warm milk, cold milk and butter. But Billee’s? Billee’s was the simplest and, I thought, the shortest recipe ever written. Pure essence of sponge!

Other interruptions were far less pleasurable and sometimes I struggled to make sense of the path life offered up, the turns in the road that shook trust and caused conflict. I especially wondered how this could happen while minding your own business at home. One sunny morning Barn had just returned from his morning school bus run and we were sitting having coffee on the Nuns’ House veranda. We could hear the sound of a distant chainsaw; not uncommon in the bush, although it seemed closer than normal. Then there was a crash too awful to ignore, the sound of a tree falling . . . more chainsawing, and another crash that split and cracked. It sounded far too close for comfort, so we jumped in the car and went to investigate.

A council team was working in Waddles Road. The men had felled a line of the tallest trees and all that was left, like amputated elephants’ feet, were their massive stumps. The Park Lane trees were gone, even the twin-trunk tree, felled in a chainsaw minute. We stopped the work by being there, which caused a confrontation, so we got straight on the phone to the council. It turned out that some of our neighbours had asked for the removal of several dead limbs overhanging the road. Instead of attending to just the dead branches, the council had negotiated with a local contractor who was prepared to clear-fell all of the trees for free, saving the council the cost of an arborist. If we hadn’t stopped the work when we did, much of Waddles Road would be bare of tall trees for the most unnecessary of reasons.

I decided to drive into town to see Audrey for dinner. Barn didn’t normally come but this time he did and it was the right thing to do. We felt taken under a wing by Mum and her Beef bourguignon with rice. We both voiced thoughts about leaving the corner, but instead reminded ourselves that, in all, we had managed to save eighteen trees along the roadside that would otherwise have been felled. From then on I changed my morning walk in the other direction—to Rowley Hill Road. Hopefully what happened that day wouldn’t happen to others who cared enough about their roadsides to protect them.

I told Paul Broad the story of Waddles Road.

‘Whatever happened to common sense?’ he questioned. ‘You don’t cut down trees in the country because a branch might fall on you! You just have to be a bit more careful when you walk underneath them.’

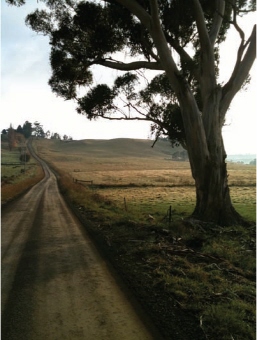

Sunrise on Rowley Hill Road.