Stalingrad is the most famous urban battle in history. It was one of the most decisive battles of World War II and established much of the public and professional military’s view of urban combat. Some of the lessons of Stalingrad are myths, and some of them are unique to the Stalingrad battle; however some remain standards of urban combat today and the battle is a worthy starting point for the study of urban combat. The positive aspects of the battle are virtually all on the Soviet side. On the German side, in contrast, the battle provides multiple lessons for how to attack a city in precisely the wrong way. At the tactical level, the battle demonstrated many of the truisms of urban combat, but it also established many of the myths of war in a concrete jungle.

The major event of World War II in 1941 was the German attack on the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. The campaign, which lasted through the summer, fall and into the depths of the winter, is one of the most studied and analyzed in military history. One of the critiques of Operation Barbarossa was that it was a strategic failure because it was not a focused attack. The Germans failed to identify a single main effort, and instead they attacked across the entire front of the Soviet Union’s western border. This lack of focus meant that, though the Germans captured immense amounts of territory and destroyed huge numbers of Soviet forces, the 1941 offensive failed to accomplish anything strategically decisive and Germany entered 1942 in a very precarious situation: not only had they provoked and wounded the Russian bear, but also, in December 1941, Germany declared war on the United States. Thus, it was imperative that Germany not only win battles in 1942, but ensure that those battles, once won, led to decisive strategic victory.

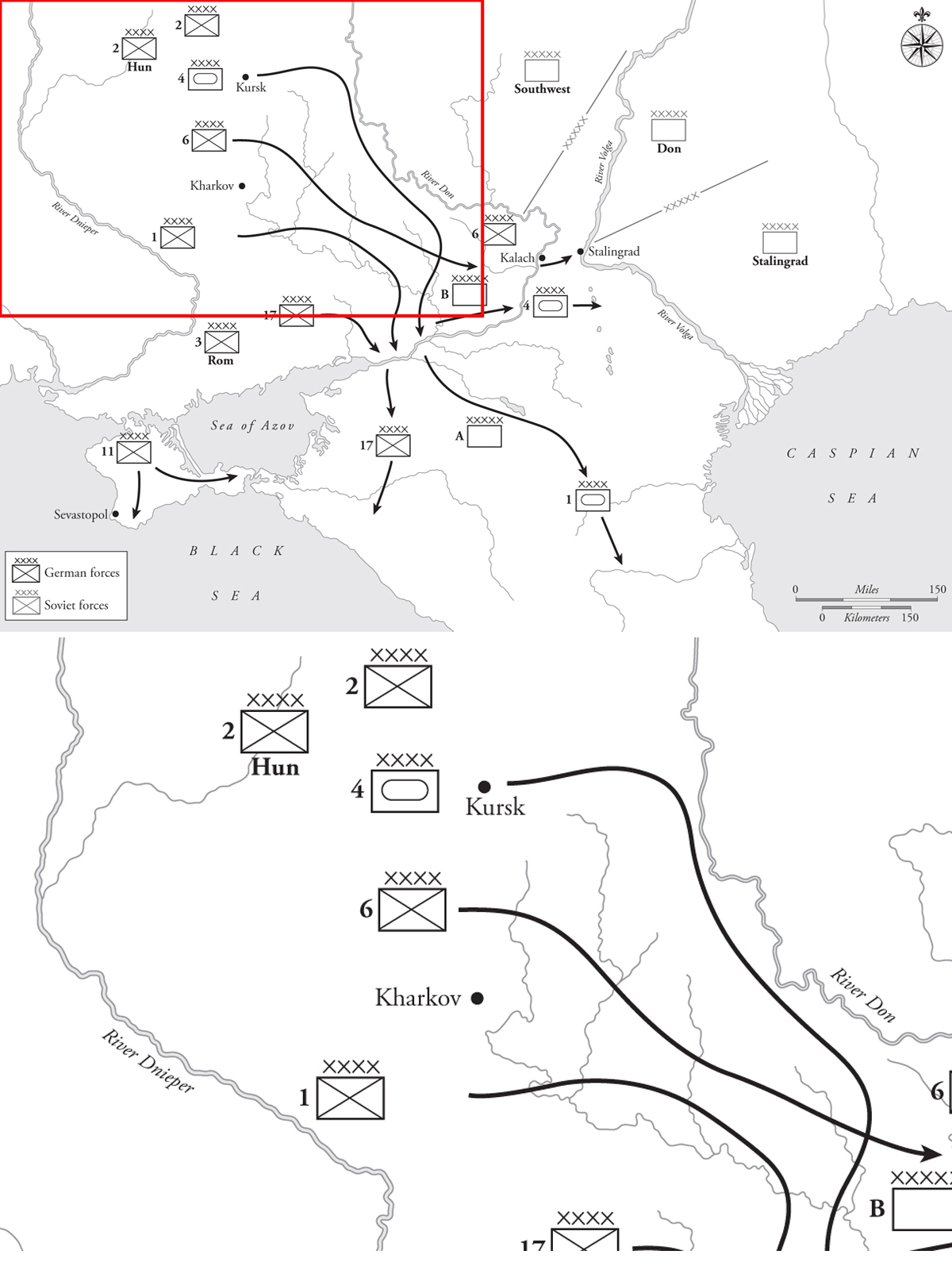

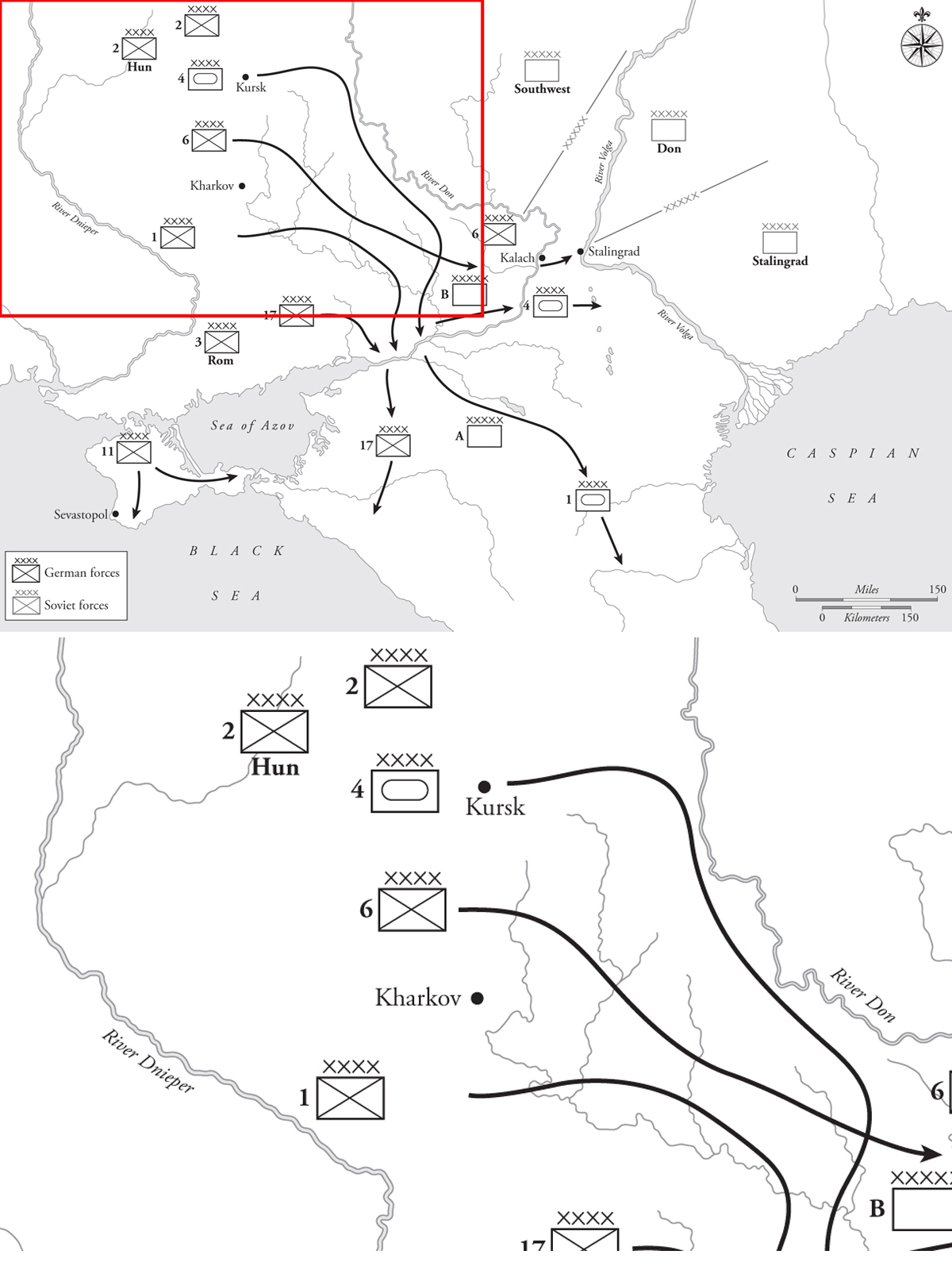

As the summer of 1942 approached, the Germans determined to reopen the offensive on the Russian front. This time, however, they would not only focus their efforts, but their chosen objective would greatly increase their strategic capabilities to pursue the war to victory: the Caucasus oil fields in southern Russia. The Germans devoted the entire Southern front to this effort. The new offensive was called Operation Blue. The Germans divided Army Group South into two Army Groups, A and B. These army groups were the primary forces in the initial attack. Army Group A, attacking in the south, would be the main effort with the mission of actually capturing the oil fields. Army Group B, to the north of Army Group A, was the supporting attack with the mission of protecting Army Group A’s left flank from a Soviet threat from the north. The Volga River was designated as the limit of the advance of Army Group B. The Germans envisioned Army Group B leading the attack before forming a defensive line along the Volga River to protect the main effort. Army Group A would then assume the lead and attack south into the Caucasus Mountains and secure control of the Caucasus oil fields. The success of the Southern Front offensive would inflict significant combat losses on the Soviets, gain a vital strategic resource for the Reich, and deny that same resource to the Soviet Union.

Army Group B, under the command of Field Marshal Fedor von Bock was composed of two subordinate armies, the Sixth Army under General der Panzertruppe Friedrich Paulus, and the Fourth Panzer Army under Generaloberst Hermann Hoth. Of the two, the Fourth Panzer Army was initially the more powerful formation, consisting of two panzer corps and two infantry corps, including a total of four panzer divisions. In contrast, the Sixth Army commanded two infantry and one panzer corps. The Fourth Panzer Army was initially located north in Army Group B’s sector and was the main attack. The Sixth Army was in the south of the army group sector and had the task of supporting the attack of Fourth Panzer Army. The city of Stalingrad was located in the center of the Sixth Army’s sector.

In late June 1942 Operation Blue was launched, a little later than originally planned. In July 1942, Fuhrer Directive No. 45 changed the course of the campaign and confirmed changes that had already occurred in the original plan. By this point in the campaign Army Group B commander, Field Marshal von Bock, had been relieved of command and replaced by Generaloberst Freiherr Maximilian von Weichs. The Fourth Panzer Army was de-emphasized in the new campaign plan, and XXVIII Panzer Corps and the 24th Panzer Division were moved from Fourth Panzer Army to General Paulus’ Sixth Army’s control. The Fourth Panzer Army itself was transferred to the control of Army Group A. The Fuhrer’s order upgraded Stalingrad to a major objective in the campaign. Finally, the attacks by Army Groups A and B were directed to occur simultaneously rather than sequentially as originally conceived. The plan as directed under Directive No. 45 became the basis of the remainder of the campaign.

The Soviets expected the Germans to resume their offensive in the summer of 1942, but they didn’t expect it to be in the south. Instead, the Soviets expected the Germans to resume their offensive in central Russia with the objective of capturing Moscow. The Soviet strategy in the summer of 1942, though, was largely governed by the leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin. Stalin insisted that the Red Army continue the counterattacks that had been initiated the previous winter as Operation Barbarossa stalled. Thus, just prior to the Germans launching Operation Blue, Soviet forces attacked further north. Eventually, after the initiation of Operation Blue the Soviet high command discerned that the German main effort was aiming south across the Don River and on to the Volga River.

The Soviet armies facing the German offensive were not the same armies that the Germans had decisively defeated the previous summer and fall. The Soviet commanders who had survived the onslaught of the previous year were a hardened and much smarter group of leaders. The ones who had failed in 1941 had been killed, captured, or arrested. Those that remained had learned important lessons about how to survive fighting against blitzkrieg. They understood that the concept of kettleschlag – the entrapment battle – was fundamental to German success. Thus, as the Germans launched their summer offense in 1942, they found it harder to conduct the large and successful entrapment operations that had characterized Operation Barbarossa the previous year. In the summer of 1942, Soviet commanders increasingly used their tank forces to slow the panzer spearheads and quickly marched their infantry out of threatening German envelopment attacks. This became easier for Soviet commanders to do over the course of the summer as Stalin realized that he could not micromanage the Red Army to victory, and increasingly turned over control of daily operations to the Soviet high command, Stafka, and individual field commanders. In the field, Stalin’s de-emphasis on political control of the military was reflected by the diminished role of political commissars who had previously been practically co-commanders of Soviet military units. Over the course of 1942 commissars were clearly placed subordinate to professional military officers on all matters related to tactical and operational decisions. This change became official in all Soviet forces in September 1942, and greatly increased the flexibility and effectiveness of Soviet commanders.

The city of Stalingrad, upgraded to a major campaign objective, was in the sector of the German Sixth Army. When World War II started, the city of Stalingrad was a major industrial center with a large population of about half a million people. Today, called Volgograd, the modern city is located on the same site as the original, approximated 200 miles north of the Caspian Sea on the west bank of the Volga River. The city’s layout was unusual for several reasons. First, it was not symmetrical. Stalingrad’s geographic shape was that of a very long rectangle that extended about 14 miles north to south along the west bank of the river, and was at its widest only about five miles from east to west. The Volga River east of Stalingrad was about a mile wide and thus a very significant obstacle.

Despite some attempts to evacuate portions of the city’s population, the war industry capability of the city was deemed too important for it to be shut down. Therefore, many civilians remained in the city operating the various war-related facilities, especially the munitions and tank factories. The city was also a magnet for refugees fleeing east before the advancing German army. Soviet industrial facilities in the city continued to operate as the battle raged and only stopped as Soviet troops retreated. Thus, through the bulk of the fighting for the city environs, more than 600,000 civilians remained in the city. To the German military, the presence of the civilians did not affect operations at all. To the Russians, the civilians were a necessary part of the defense. They were organized into labor units that assisted in building defensive positions and they continued to work in the industrial facilities. As those facilities were gradually captured by the Germans the civilian population fled or were ferried to the east side of the river. Throughout the most intense fighting for the city as many as 50,000 civilians remained within the area of the battle.

Map 2.1 German Summer Offensive, 1942

A key to successful urban combat is anticipating the urban battle and preparing for it. The German commanders understood this. However, the operation to capture Stalingrad was not initially subject to close scrutiny because it was only a secondary objective of the campaign, and not decisive to obtaining the German army’s objective for the summer campaign, the Caucasus oil fields. In fact, the original plan had no requirement to capture Stalingrad, but rather merely required the German forces to contain Soviet forces and halt the production in the factories located there.

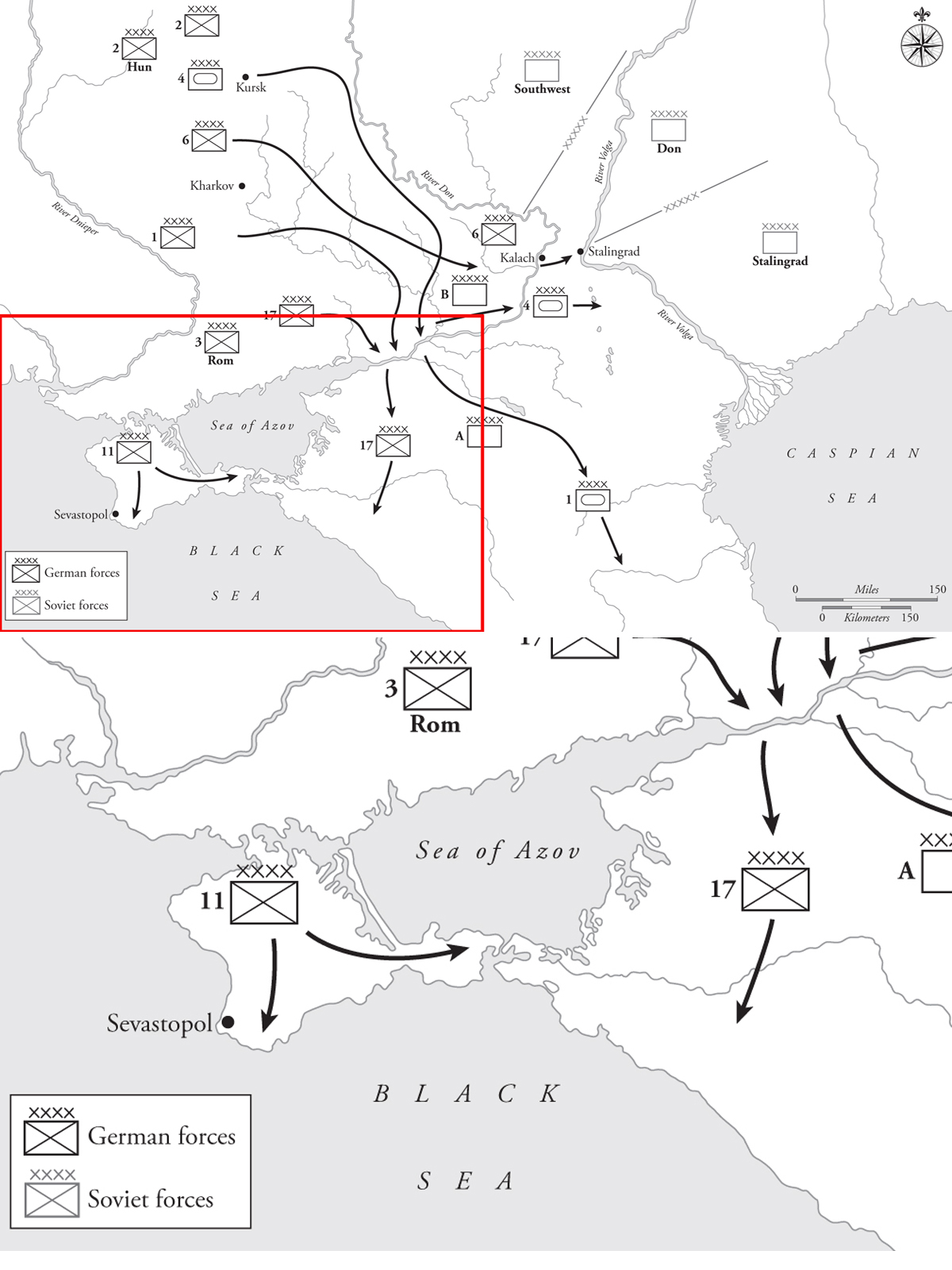

The German army had had experience of urban warfare during the Barbarossa campaign and earlier in the summer of 1942. They had captured numerous Russian cities including Minsk in the Ukraine, and Sevastopol in the Crimea, and as they approached Stalingrad, the northern army group was laying siege to the former Russian capital, Leningrad. Dozens of other medium-size Russian cities had been isolated by the German panzers and then captured when the German infantry caught up with the panzer columns. Early in Operation Blue, the Fourth Panzer Army became involved in a tough urban battle in and around the important transportation hub city at Voronezh. Because of that experience the German army had adequate knowledge of the intricacies and challenges of tactical urban warfare. Fighting the urban battle tactically was not a concern of the German military commanders as they approached Stalingrad. However, Hitler’s role in operations was a concern. Hitler, as the Nazi dictator of Germany, was the key to the German military failure at Stalingrad.

Operation Blue began in June 1942 and by mid-July had made important progress. The Germans, inhibited by a shortage of tanks, and fuel for the tanks they did have, found it difficult to complete the large encirclement operations that had characterized Barbarossa the previous year. Inadequate strength in troops, equipment, and fuel caused short delays throughout the approach to Stalingrad, which proved crucial. Still, there was significant operational success and the German Sixth Army had captured tens of thousands of Soviet troops and destroyed dozens of divisions by mid-summer. Even so, Soviet commanders managed to keep many of their major formations from being trapped and, though they lost most of their armored forces in the great retreat through southern Russia, they retained the core combat power of their divisions and avoided decisive defeat.

In the middle of July Hitler intervened in the summer campaign. He was unhappy with the rate of advance and ordered the launching of the offensive into the Caucasus as the advance to the Volga was ongoing. Thus, contrary to the original Operation Blue plan, which called for a sequenced advance of first Army Group B and then Army Group A attacking south into the Caucasus, Hitler Directive No. 45 ordered both army groups to attack simultaneously. This had several immediate effects. It strained the already overstrained logistics system. It also created two weaker efforts in the place of one strong attack. Finally, the two army groups’ objectives were on divergent axes, so the German formations moved further away from each other as the attacks progressed, to the point where they were not within supporting distance of each other.

As important as changing the sequencing of the offensive were Hitler’s changes to the orders regarding Stalingrad. Stalingrad was redesignated as a primary objective of the campaign. This change not only required the Sixth Army to capture the entire city, but required that resources which may have been used to reinforce the attack into the Caucuses were diverted to the Stalingrad battle.

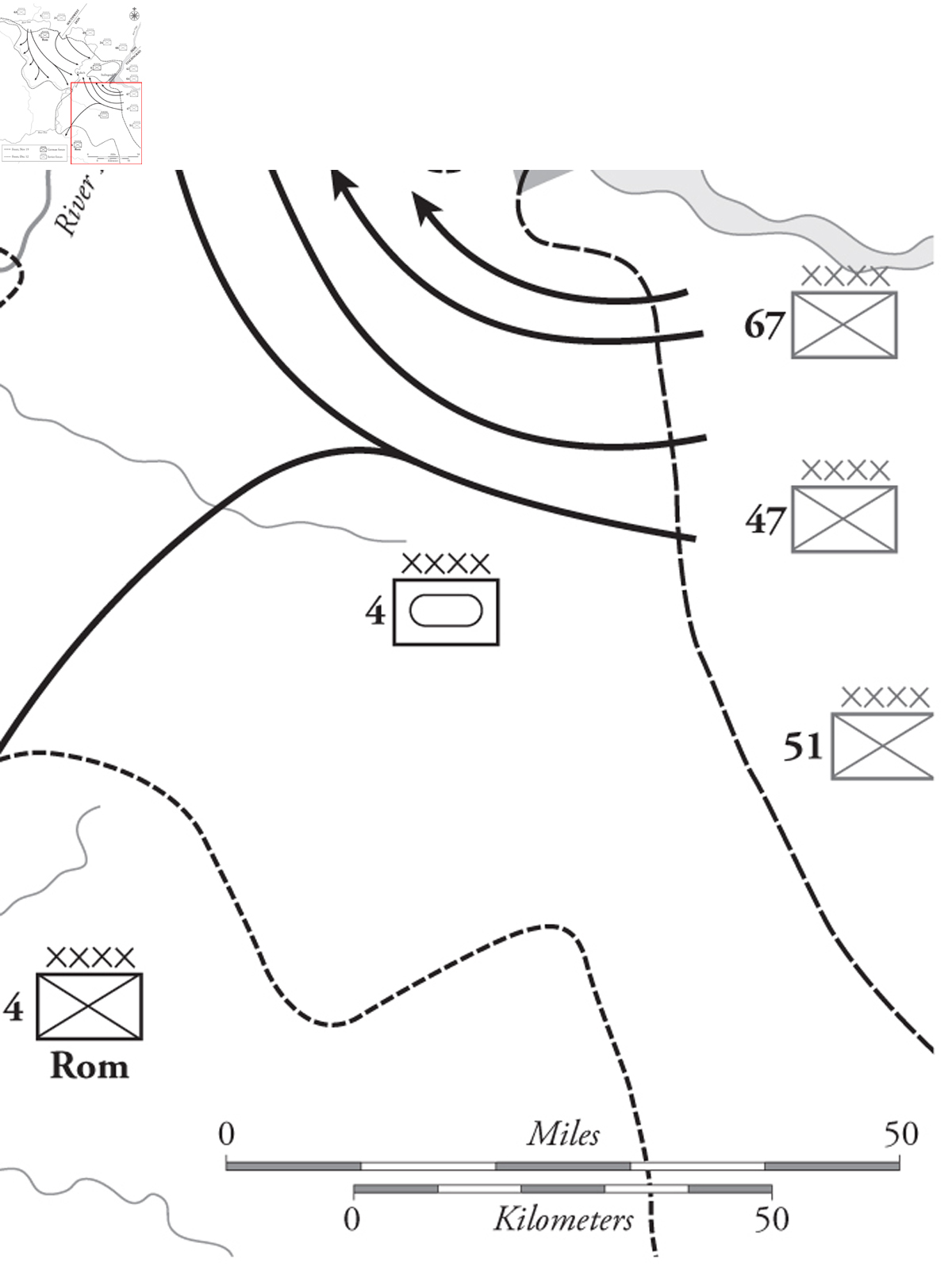

The Germans began their final push to capture Stalingrad at the end of August 1942. By August 22, Sixth Army’s XIV Panzer Corps had entered the northern suburbs of the city and the following day the panzers reached the Volga north of the city. The rest of the Sixth Army, and XXVIII Panzer Corps under control of Sixth Army, pushed to the outskirts of the city. The XXVIII Panzer Corps managed to break through the Soviet Sixty-Fourth Army defending the southern portion of the city and race almost to the Volga threatening to trap part of the Sixty-Fourth Army and all of the Soviet Sixty-Second Army in the city’s outskirts. This success caused the two Soviet armies, the Sixty-Second and Sixty-Fourth, to give up the outer ring of the city’s defenses and withdraw into the city to avoid the trap. Thus, by the end of August the Germans were firmly in possession of the outskirts of the city and threatened it from three directions: north, west, and south. It appeared the fall of the entire city would happen in a matter of weeks.

The fighting for Stalingrad proper began on September 14, as German forces attempted to force their way into the city center. The battle for the city directly involved three German army corps: the XIV Panzer and LI Corps of the Sixth Army, and the XXVIII Panzer Corps of Fourth Panzer Army. The three German corps were opposed directly by two Soviet armies: the Sixty-Fourth and Sixty-Second Armies of the Stalingrad Front. The initial attacks were costly but successful. After about ten days of very intense fighting the two panzer and two infantry divisions of XXVIII Corps managed to destroy most of the Sixty-Fourth Army in the southern part of the city and seize about five miles of the Volga riverbank. In the center of the city, the combined forces of the LI and XIV Panzer Corps pushed the divisions of the Soviet General Vasily Chuikov’s Sixty-Second Army back toward theVolga and reduced the Soviets’ defensive parameter by half.

Despite the successes, the attacks of mid-September did not accomplish the Sixth Army’s mission. The task of the army was the capture of the city, not just, as it had initially been, to control the city. Thus on September 27, Sixth Army renewed the attacks to eliminate the presence of the Soviet Sixty-Second Army on the west bank of the Volga. The initial attacks had severely depleted many of the veteran units of the Sixth Army, particularly in the center of the line where the most significant attacks occurred. To compensate, most of XXVIII Panzer Corps was moved from the south into the central part of the sector. This gave the Germans two strong panzer divisions (the 24th and the 14th) and two motorized infantry divisions in the center.

The Soviets anticipated the German offensive and took steps to meet it. Their excellent intelligence network inside the city informed them that the focus of the attack would be in the center and north, aimed at the major Soviet defenses based at three large factory complexes in northern Stalingrad. From north to south these were the tractor factory complex, the Barrikady weapons factory complex, and the Red October factory facilities. These complexes were huge self-contained communities which included the factories themselves and the workers’ housing buildings. The buildings were massive structures constructed of steel girders and reinforced concrete. Many of the factory buildings included massive internal workshops large enough to house the emplacement of tanks and large-caliber guns to participate in the fight inside the building. After repeated air and artillery attacks, the complex and formidable defensive qualities of the buildings were actually enhanced due to extensive damage and accumulated rubble. To this the Soviet infantry added barbed wire, extensive minefields, deep protected trenches, and bunkers. By the end of September, the Soviet defensive positions in Stalingrad were every bit as formidable as the most notorious defenses of World War I.

The second major German attack into the city lasted ten days, from September 27 to October 7, and involved 11 full German divisions including all three panzer divisions. Like the first attack, it was successful and the Germans managed to capture two of the three major factory complexes: the tractor factory and the Barrikady factory. They also eliminated the Orlovka salient which was a deep Soviet defensive salient that had remained in the northern part of the city. Despite steady Red Army reinforcement which consistently frustrated a decisive German breakthrough, by the end of the attack the Sixty-Second Army was reduced to a tiny strip of the west bank of the Volga which at its widest was perhaps 2,200 yards (2,000 meters).

The third major attack to secure the city began on October 14, 1942. Three infantry divisions, two panzer divisions, and five special engineer battalions were committed to the attack – in total over 90,000 men and 300 tanks on a 3-mile front. For another 12 days the Germans ground forward, systematically reducing Russian strongpoint after strongpoint. The Soviets fed additional troops across the Volga but the defenders were running out of space. When the German offensive finally paused on October 27, they held 90 percent of Stalingrad. Only part of the Red October steel factory was outside their control. The Sixty-Second Army was fragmented into small pockets and most of its divisions were completely wiped out. All sectors of the remaining Soviet defenses were subject to German observation and attack. But the German attacks ended without achieving their objective: capture of the city of Stalingrad. As the month came to a close, shortages of troops, ammunition, tanks, and pure exhaustion of the remaining troops made further offensive operations by the Germans impossible.

Winter arrived in Stalingrad on November 9 as temperatures plunged to -18°C. The fighting, however, did not stop. The Germans were no longer capable of large-scale offensive operations but small raids and attacks continued as they attempted to eliminate the remaining Soviet strongpoints. On November 11, battle groups from six German divisions, led by four fresh pioneer battalions, launched the last concerted German effort to secure the city before the coming of winter. It, like all previous German offenses, took ground and punished the Soviet defenders, but ultimately fell short of its objective. In the LI Corps, under General Walther von Seydlitz, 42 percent of all battalions were considered fought-out and across the entire Sixth Army most infantry companies had fewer than 50 men and companies had to be combined in order to create effective units. The 14th and 24th Panzer Divisions both required a complete refitting in order to continue operations in the winter. In short, by mid-November the combat power of the German Sixth Army was almost completely spent after more than two months of intense urban combat.

The German high command, and Hitler in particular, were desperate for a victory at Stalingrad. Desperation does not make for good military decision-making, and over the course of the campaign the German decision-making evolved from taking great risks to simple gambling. By October, the Germans were gambling that the Soviet high command was incapable of simple and obvious military judgment, which was all that was required to recognize early in the battle what an operational opportunity the shaping of the battle could provide to the Soviet high command.

Early in September the senior leadership of the Soviet Union, Premier Joseph Stalin, and generals Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Georgi Zhukov met and identified the operational opportunity that the German disposition at Stalingrad presented. The opportunity was obvious from the map. The Sixth Army was extended deep into Russia at the end of a very long supply line. Long flanks were exposed both north and south of the advance to Stalingrad. An examination of German force distribution reinforced the vulnerabilities of the geometry of the Army Group B front. The vast preponderance of the German combat power, 21 divisions, was concentrated at the very tip of the salient, in Stalingrad. The flanks were comparatively lightly held. Moreover, the bulk of the units holding those flanks were inferior allied units: Italian, Hungarian, and least effective of all, Romanian. These allied formations had been injected into the line in July and August to relieve German formations for employment in Stalingrad. Further exasperating already precarious operational dispositions was the fact that neither Sixth Army nor Army Group B held any significant operational reserves to respond to an emergency. In addition, the units that were best suited to constituting a reserve, the mobile panzer and panzer grenadier divisions, were seriously understrength, short on fuel, and many were decisively engaged in the Stalingrad street fighting and therefore unavailable. The primary Army Group reserve was XLVIII Panzer Corps. The corps consisted of the German 22nd Panzer Division and the Romanian 1st Armored Division. Both units were understrength, and the Romanian division was absolutely no match for Soviet armor. The Germans could not have offered Stalin and Zhukov a more lucrative and tempting target if they had consciously tried to do so.

Through all of September and October the Red Army prepared for Operation Uranus, the counteroffensive against Army Group B. The Russians carefully moved units forward at night to avoid German detection. They used intelligence gathered from captured prisoners and a partisan intelligence network to carefully plot German dispositions. Secrecy was extreme and even senior commanders, such as General Chuikov in Stalingrad, were unaware of the preparations for the counterattack. The German command was the most unaware of what was happening. German intelligence not only was completely unaware of the massive Soviet buildup north and south of Stalingrad, but they were convinced that the Red Army had no significant operational reserves. The performance of German intelligence throughout World War II was consistently poor, and often, as at Stalingrad in November 1942, had disastrous consequences.

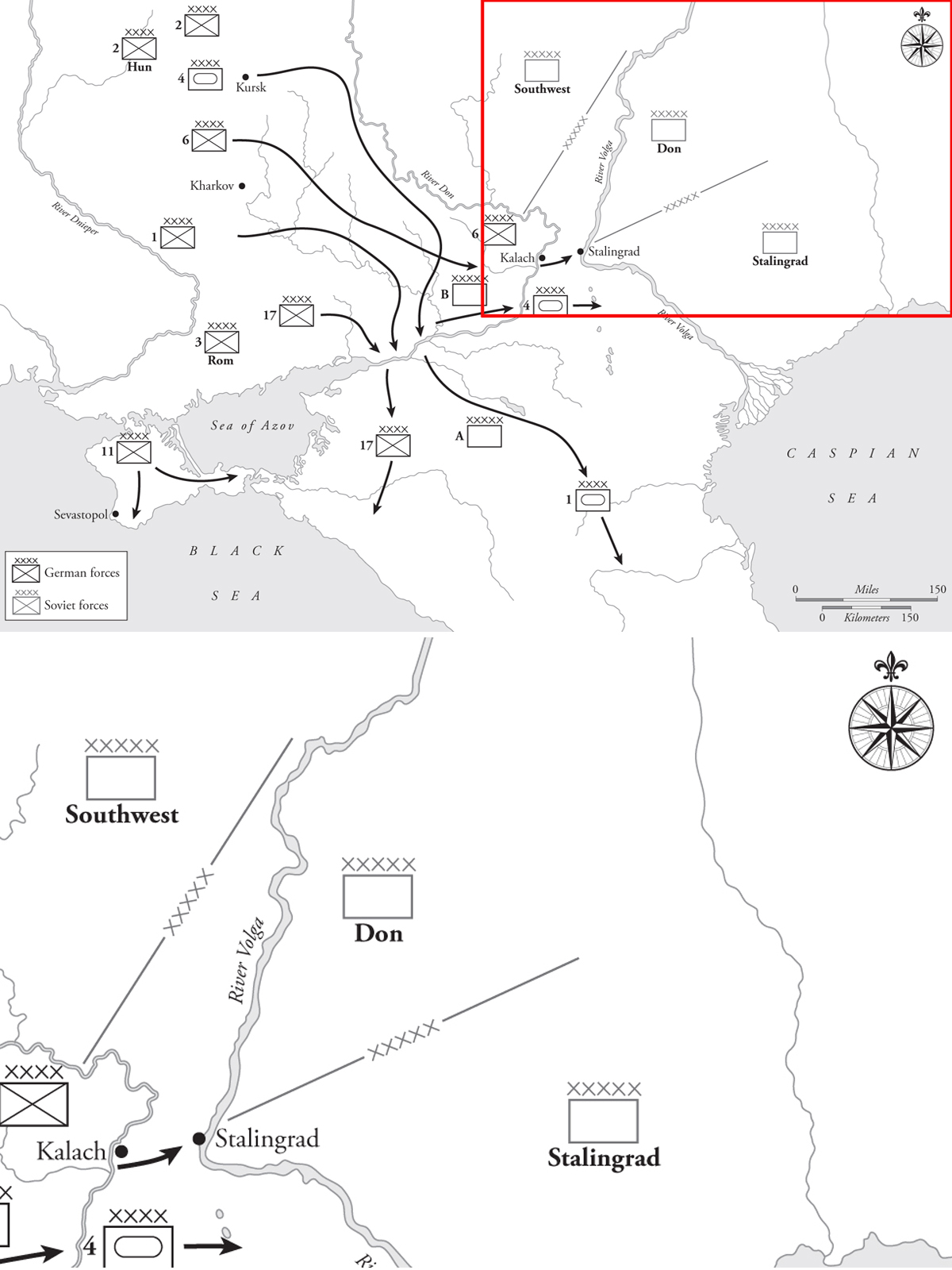

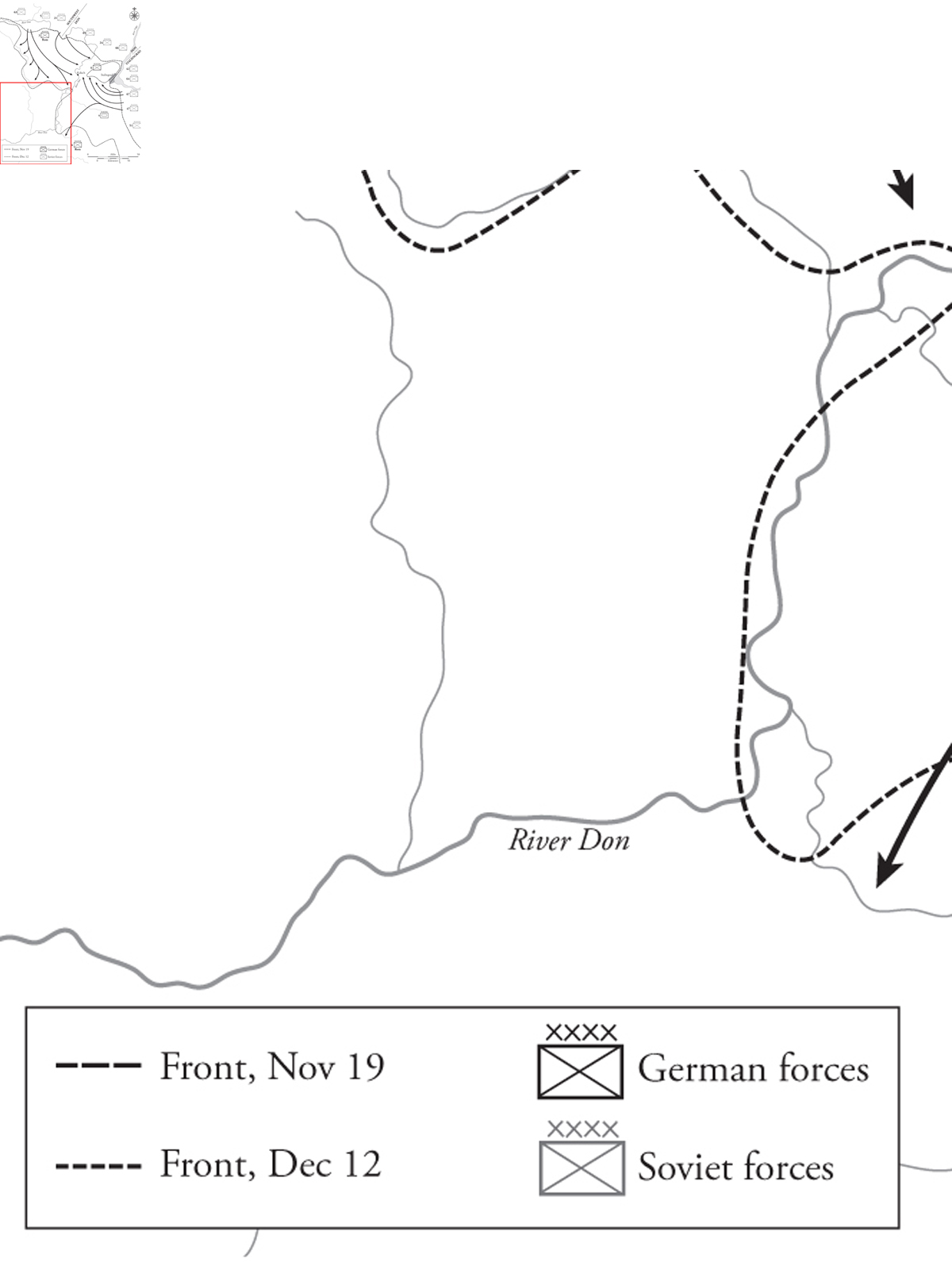

In preparation for Operation Uranus, the Soviet Army reorganized its command structure. Three front commands were created in the Stalingrad area. The Southwest Front, under General Nikolai Vatutin, was far to the north and west of Stalingrad. The Don Front, under General Konstantin Rokossovsky was located directly north of Stalingrad. The Stalingrad Front, under General Andrei Yeremenko, had responsibility for Stalingrad itself and units to the south of the city. The plan called for the Southwest and Don fronts to launch attacks deep into the rear of Sixth Army. The Southwest Front’s Fifth Tank Army would attack the Romanian Third Army over 100 miles west of the Sixth Army’s main forces in Stalingrad itself. Simultaneously, the Stalingrad Front would counterattack 50 miles south of the city, aiming at the 51st and 57th Corps of the Romanian Fourth Army.

On the morning of November 19, the attack began. All across the Southwest Front Soviet artillery blasted huge holes in the Romanian lines which were quickly driven through by Russian armor and horse cavalry. The Soviet operational technique was simple: massive artillery bombardment shocked and suppressed the defending Romanian infantry; Soviet armor rolled over the still shocked Romanians who were woefully short of antitank guns and had no armor reserve. Soviet horse cavalry followed closely behind the armor to protect its flanks. Finally, Soviet infantry moved forward and mopped up the remaining isolated Romanian positions. The Soviet assault tactics were extremely effective against the poorly equipped and led Romanians, and Soviet armor formations quickly penetrated and fanned out into the Romanian and German rear areas. The objective of the Southwest Front was the west bank of the Don River and the Sixth Army logistics base at Kalach on the east bank of the Don River. Kalach and the vital bridge over the Don located there were captured on November 22, a mere three days after the attack began.

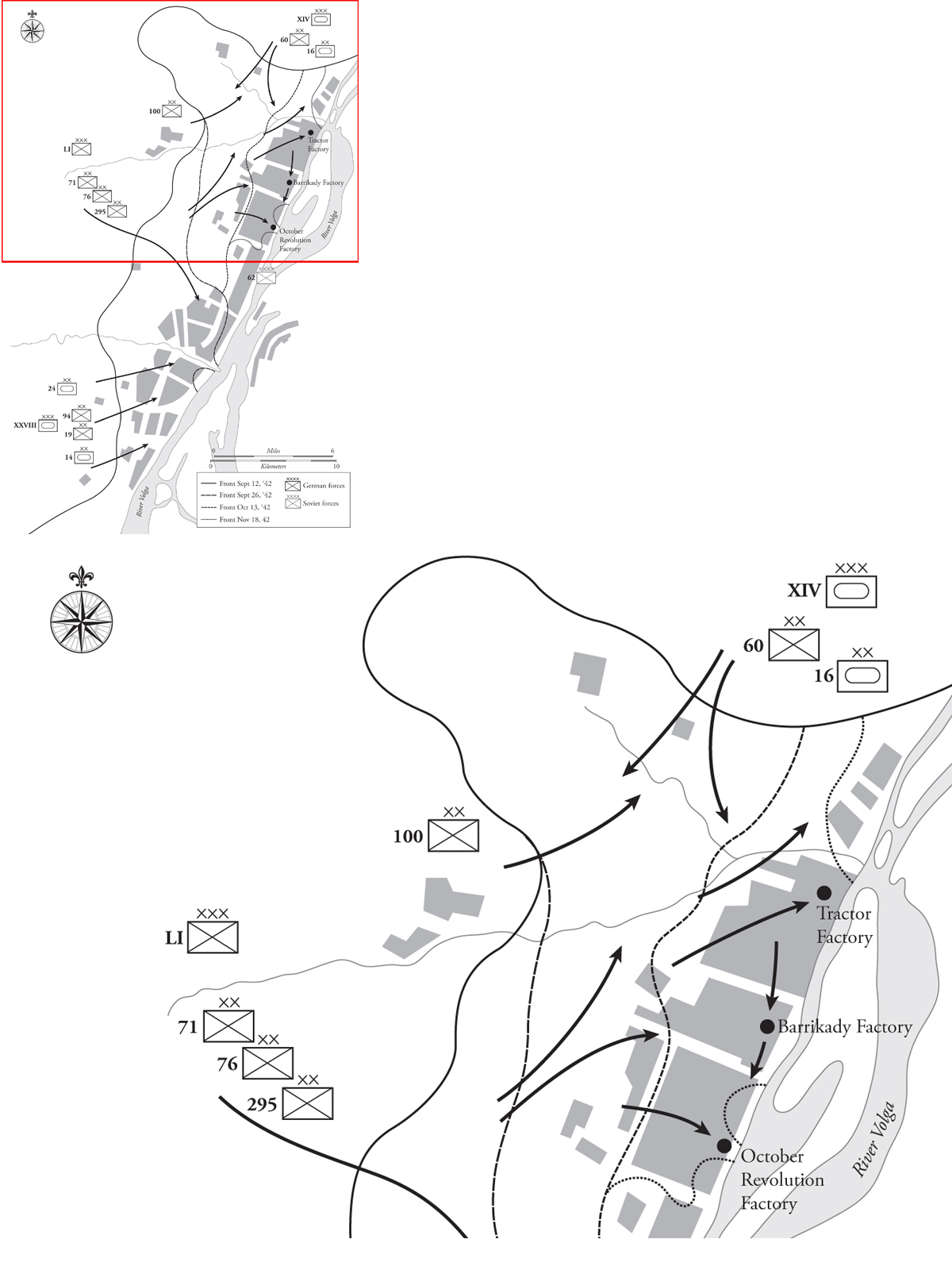

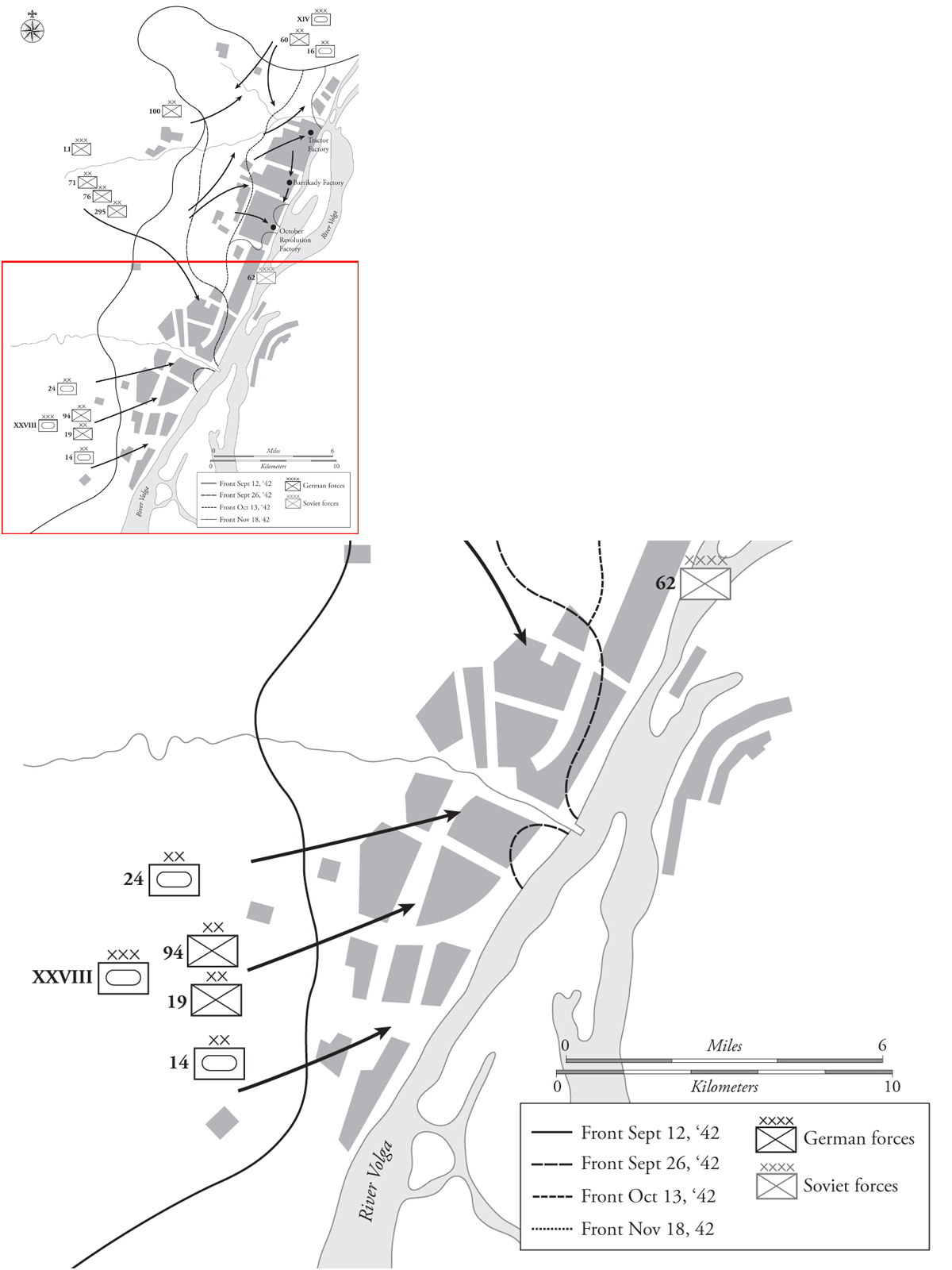

Map 2.2 The Sixth Army Attack into Stalingrad, September–November 1942

On November 20 the Stalingrad Front launched its attack on the Romanian Fourth Army. The pattern to the northwest was repeated south of Stalingrad. The Romanian forces were quickly overrun by Soviet armor formations which proceeded to advance rapidly against light opposition to the west and northwest. On November 23, four days after the beginning of the offensive, armored forces from the Don Front linked up with forces from the Stalingrad Front just east of Kalach and effected the complete isolation of the Sixth Army and attached troops around Stalingrad.

The battle for Stalingrad was decided on November 23 when the Red Army managed to isolate the German Sixth Army in and around the city. In three months of combat prior to the end of November, the German forces had been unable to isolate the Soviet Sixty-Second Army in the city and therefore the battle had raged on. The Germans had never contemplated isolating Stalingrad by attacking across the Volga River. In contrast, in four days the Soviets surrounded the city and sealed the fate of the Sixth Army. Approximately 250,000 Axis troops were trapped in the kessel. Over the next two and a half months the Soviets gradually pressed against the perimeter of Sixth Army while the rest of the German army watched on helplessly. Finally, the bulk of the German troops surrendered on January 31, 1943. The remaining holdouts, after enduring a withering Soviet artillery barrage, surrendered on February 2. In all the Russians took in almost 100,000 prisoners as the five-month battle for the city ended. In total, the losses at Stalingrad were immense. In the battle and campaign, which included the Soviet counterattack, the Germans lost 400,000 men, and the Soviets lost 750,000 killed, wounded, and missing. Allies of the Germans – the Italians, Hungarians, and Romanians – lost another 130,000, 120,000, and 200,000 respectively. Thus total casualties on both sides exceeded one million men. Of the 600,000 civilians who lived and worked in Stalingrad and its suburbs, no one knows how many died, although 40,000 were reported killed in the initial air attacks against the city. Hundreds of thousands of civilians became casualties over the course of the five-month battle, and those remaining became refugees. Only 1,500 civilians remained in the city at the end of the battle. In terms of raw casualty numbers, the battle for Stalingrad was the single most brutal battle in history.

Though the German army had acquired experience of urban fighting during the fall of 1941, the individual divisions in Stalingrad had to develop their own version of city fighting for the unique Stalingrad situation. Stalingrad was different from other cities for several reasons. One was the massive amount of destruction that had been inflicted upon the city, destruction which continued and increased over time. The second was the nature of the buildings in Stalingrad. They were massive concrete affairs which, when surrounded by rubble following artillery and air bombardment, were virtual fortresses. The Germans found that the most effective tactic was to combine infantry and armor into teams. These teams were supported by artillery and closely supported by the Luftwaffe. Stalingrad was the last great performance by the fabled German Stuka dive-bombers.

Typically, German attacks followed a pattern: Luftwaffe air bombardment, followed by a short artillery barrage, and then the advance of German infantry followed closely by panzers in support. This pattern generally ensured success. Panzers, though not optimized for city warfare, were absolutely critical to it, and the three panzer divisions that fought at Stalingrad were a key part of most of the Sixth Army’s tactical successes. The problem the Germans had tactically was that they simply did not have enough panzers, infantry, and artillery to execute the tactics they employed with sufficient vigor to overcome the Russian defenders quickly. In the course of the German attacks in Stalingrad, virtually all the attacks were successful. However, they were never as fast as the Germans wanted or expected them to be, and were always more costly than the Germans could afford. The German army could be, and was, successful in urban combat in Stalingrad, but at an unacceptable price in time and casualties.

In the rubble of Stalingrad, the disparity between German and Soviet tactical capabilities, which was very prominent in the open battles of maneuver on the Russian steppe, was reduced significantly. The German army excelled at operational warfare: the close coordination of all arms at the division and corps level of command to achieve rapid and decisive effects across great distances. In urban combat, the important distances were blocks – divisions and corps could not maneuver, and command and coordination at the highest levels was relatively simple and not very important. Thus, the strengths of the German military machine were fairly irrelevant to the battle. Instead, the battle devolved to tactical competence at the battalion level and below, combat leadership, and the psychological strength of the individual soldier. The Wehrmacht had these characteristics in great abundance. However, so did the Soviet army. Thus, unlike in operational maneuver warfare, in urban combat the two sides were both fairly competent, and thus very evenly matched. These organizational circumstances were a recipe for a long and bloody battle. The Red Army, and in particular the Sixty-Second Army, augmented the natural strength of the Russian infantry in close combat and the urban terrain with several innovative tactics which made them more formidable in urban combat than the Germans expected.

One of the most effective and feared German weapons at Stalingrad was the venerable Stuka dive-bomber. Weather permitting, all major German attacks were preceded and closely supported by the Stukas of Luftflotte IV under Generaloberst Freiherr Wolfram von Richthofen. To lessen the effectiveness of this weapon, as well as of German artillery, General Chuikov ordered that all front-line units stay engaged as closely as possible to the Germans. The Sixty-Second Army “hugged” its German adversaries so that German bombardment could not engage the front-line Russians without hitting their own troops. This resulted in there being virtually no “no-man’s land” on the Stalingrad battlefield. Across the entire front Red Army positions were literally within hand-grenade range of the German positions. Thus, attacking Germans were often confronted by defenders who were unaffected by the pre-attack artillery or air bombardment.

After the initial penetration of the city, the Soviet armor of the Sixty-Second Army was not used in a mobile manner. The tanks, instead, were dug deep into the rubble and heavily camouflaged. Often they were invisible from more than a few yards away. They were placed on the routes most likely used by German tanks and supporting vehicles, and invariably were able to fire the first shot. The short ranges, careful preparation, and ability to fire first gave the Russian tank crews better than even odds despite the general superiority of German crews. In total the German and Soviets together employed over 600 tanks inside the city.

One of the most innovative and effective ideas developed by the defending Red Army was the idea of shock groups. Shock groups were non-standard small assault units organized to conduct quick attacks on specific German positions. They often attacked at night. Typically they consisted of 50–100 men. They were lightly equipped so that they could move quickly and silently through the city. The groups were led by junior officers; they used a variety of weapons but relied heavily on sub-machine guns and grenades. They also included engineers for breaching doors and other obstacles, snipers, mortar teams, and heavy machine guns to defend the newly won positions. Shock groups relied extensively on the initiative of the junior leaders to determine how best to assault an objective. Many of the men in the group were volunteers who relished an opportunity to take the fight to Germans, despite the Sixty-Second Army’s overall defensive stance. Because of this aggressiveness and the latitude allowed the junior leaders, shock groups were both very effective and also very much a departure from standard Soviet tactical practice which was typically very controlled. The departure from standard doctrine which shock groups represented in the Soviet army indicated the desperate measures that were permitted on the Soviet side during the battle. They proved to be a very effective tactic during the second part of the battle, after September, and were an indicator of the tactical parity that existed in close urban battle. Though shock groups were copied by other Soviet armies in subsequent urban combat during World War II, as the Soviet Union gained the operational and strategic initiative the groups became more and more standardized, larger and more heavily equipped (to include tanks and artillery). As the war progressed, they were permitted less freedom of action. Soviet shock groups, as they existed by the end of the war, bore little resemblance to the highly effective organizations developed during the battle for Stalingrad.

One of the major special tactics that the Russians developed and utilized in the Stalingrad battle was snipers. Though the Red Army had a small number of trained snipers as part of its organizational structure, in Stalingrad the employment of snipers became a largely ad-hoc movement initiated by individual soldiers and eventually embraced and encouraged by commanders. Early during the battle self-motivated snipers acquired rifles with telescopic sights and then got permission from their commanders to go on individual “hunting” missions. Red Army commanders, including the army commander General Chuikov, saw the snipers as brave and angry soldiers whose frustration and hatred could be channeled by the army into a useful outlet. Thus, sniping became a sanctioned individual mission and the success of snipers was widely publicized both within Stalingrad and throughout the Soviet Union to encourage morale among the soldiers at the front and the civilians at home. Sniping was inordinately successful in Stalingrad for many reasons: the density of troops in the built-up area; the protracted nature of the battle, which led to troops becoming careless, and allowed snipers to learn the patterns of the enemy; the terrain, which allowed snipers to stalk and hunt targets with both cover and concealment; and the proximity of the enemy, which made effective sniping relatively easy – many targets were less than a hundred yards away. The Russian command carefully tracked the progress of individual snipers and trumpeted their success in propaganda. The most famous of the snipers, Private Vasily Zaitsev, had well over 200 sniping kills, and was one of several snipers who killed more than a hundred Germans. The effectiveness of the Russian snipers was not only a major morale booster to the Sixty-Second Army, it had tremendous adverse psychological effects on the German troops who never knew when a shot would crack and a man would drop to the ground.

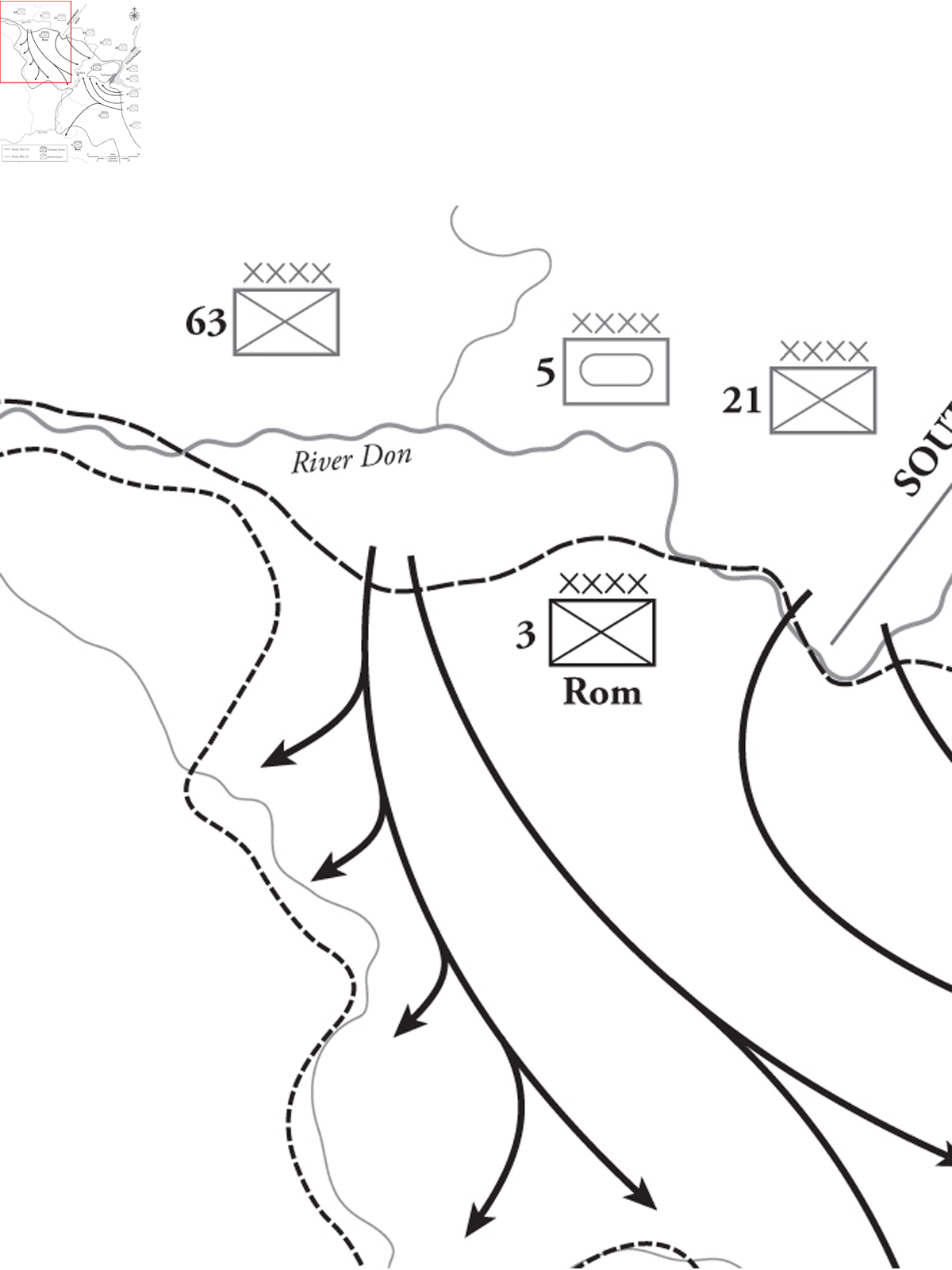

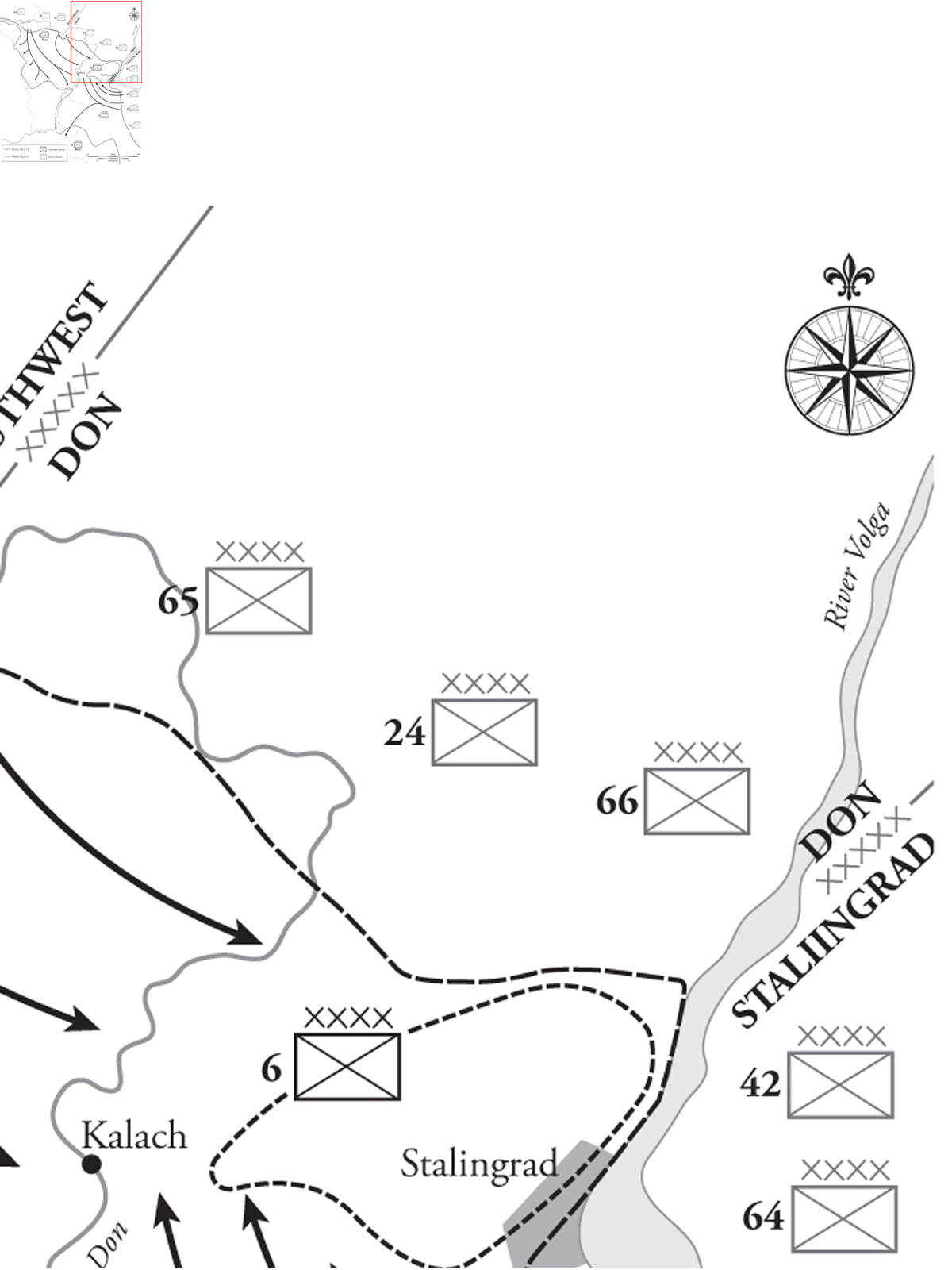

Map 2.3 The Soviet Counteroffensive, November 1942

Armor, for both the Soviets and the Germans, proved to be extremely important to successful city fighting. Soviet armor was primarily used in stationary firing positions. Though stationary, the armored vehicles were heavily camouflaged and carefully sited to cover avenues that the attacking Germans could not avoid. Unlike antitank guns and machine-gun positions manned by infantry, the stationary tanks were immune to all but a direct hit by artillery and often required an enemy tank or assault gun to knock them out. They were important anchors in the Russian defensive scheme. German tanks were equally invaluable. They provided the firepower and shock action necessary for German infantry to overpower skillfully defended Russian defensive positions – particularly bunkers and dug-in Soviet tanks. Their firepower made up for the relatively low numbers of infantry in the German force. They provided an important psychological advantage that boosted German infantry morale and intimidated defending Soviet infantry. Finally, their mobility meant they could be rapidly repositioned to weight a particular sector or exploit success. It was no coincidence that the major successes achieved by the Germans in their four major attacks in the interior of Stalingrad included major components of German armor. Rather than having a limited role in urban operations, Stalingrad demonstrated that armored forces were key and essential to successful urban operations.

The battle for Stalingrad was simultaneously a tribute to Soviet army skill and endurance, and an example of the incompetence of German senior leaders. German commanders executed Operation Blue poorly. A large factor in that poor execution was the inept strategic and operational guidance and orders of Adolf Hitler. Several senior officers were removed from their positions because of their conflicts with Hitler. Among these were the chief of the Army General Staff, General Franz Haider, and the commander of Army Group B, General Fedor von Bock. In both cases it was directly due to Hitler’s refusal to act in accordance with a real appraisal of the battlefield. Hitler personally took command of Army Group South and gave very specific operational and tactical guidance down to battalion level through much of the battle. He made the key flawed decisions to launch operations into the Caucasus before the Volga line was secure; to elevate Stalingrad from a secondary campaign objective to a primary campaign objective; to require all of Stalingrad be captured not just controlled; and to hold fast as the Sixth Army was surrounded and later not to break out when the 6th Panzer Division and Field Marshal Erich von Manstein’s Army Group Don was only 20 miles away. It is doubtful that any army could recover at the tactical level from the terrible position the Sixth Army ended up in as a result of Hitler’s amateurish involvement in operations. However Hitler did not single-handedly set up the conditions for the Stalingrad defeat. Collectively the senior German military was also guilty of incompetence for ignoring the weaknesses of the allied armies protecting Sixth Army’s flanks; not understanding the limited capabilities and strength of XLVIII Panzer Corps, the Army Group reserve; and completely underestimating the Soviet military’s competence, strength, and intentions prior to the launching of Operation Uranus. It was the sum of the failures of Hitler and other senior leaders that led to the debacle at Stalingrad. The great lesson of Stalingrad is that urban warfare, for all of its painful brutality at the tactical level, is often won or lost due to operational and strategic decisions made at levels above the tactical and often immune to the conditions of the concrete hell of urban warfare.