Eighteen months after Stalingrad, on the opposite side of the European continent, the US Army was tested in major urban combat of when the Americans approached the German city of Aachen in October 1944. The battle for Aachen demonstrated many of the characteristics of urban warfare seen at Stalingrad. It also highlighted some of the basic requirements of successful urban operations that were missing in the Stalingrad battle. Finally, Aachen demonstrated some uniquely American characteristics of urban operations. Though not conducted on the same scale as Stalingrad, the battle for Aachen was nonetheless one of the key battles on the Western Front of World War II as the Allies sought, and the Germans contested, the capture of the first German city of the war.

The Western Allies opened the Western European Front on June 6, 1944, when troops were landed at Normandy. For the next seven weeks German and Allied forces dueled in the hedgerows of Normandy. The terrain suited the German defense and the Allies were continuously frustrated in their attempts to break out of their beachheads. Finally, on July 25 the American First Army’s Operation Cobra succeeded in breaking out of the beachhead. In the next weeks a battle of maneuver ensued. A German panzer counterattack was defeated at Mortain, August 7–13, 1944. Meanwhile, the Americans activated General George Patton’s Third Army which quickly captured the Brittany Peninsula, turned east, and dashed through light resistance across central France.

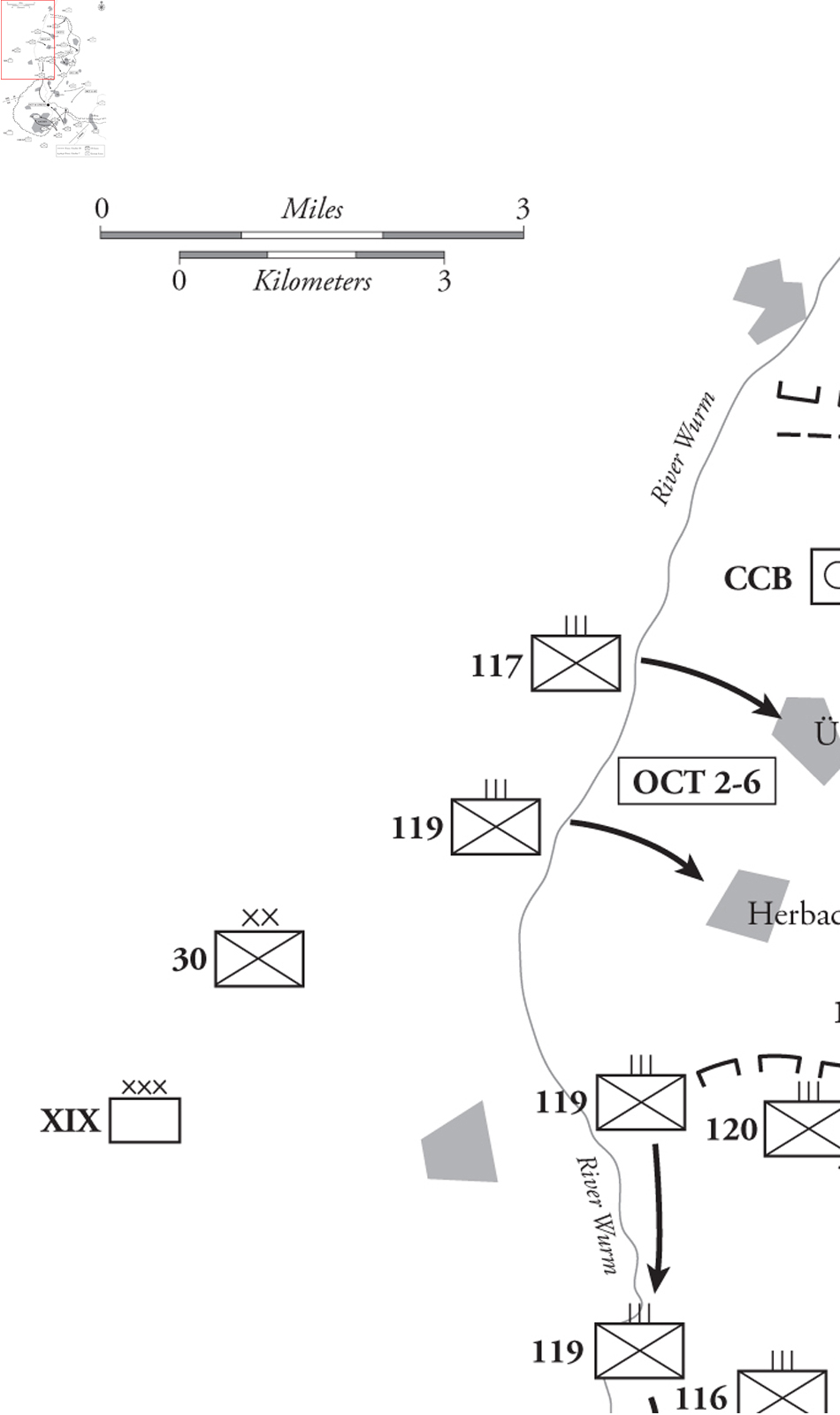

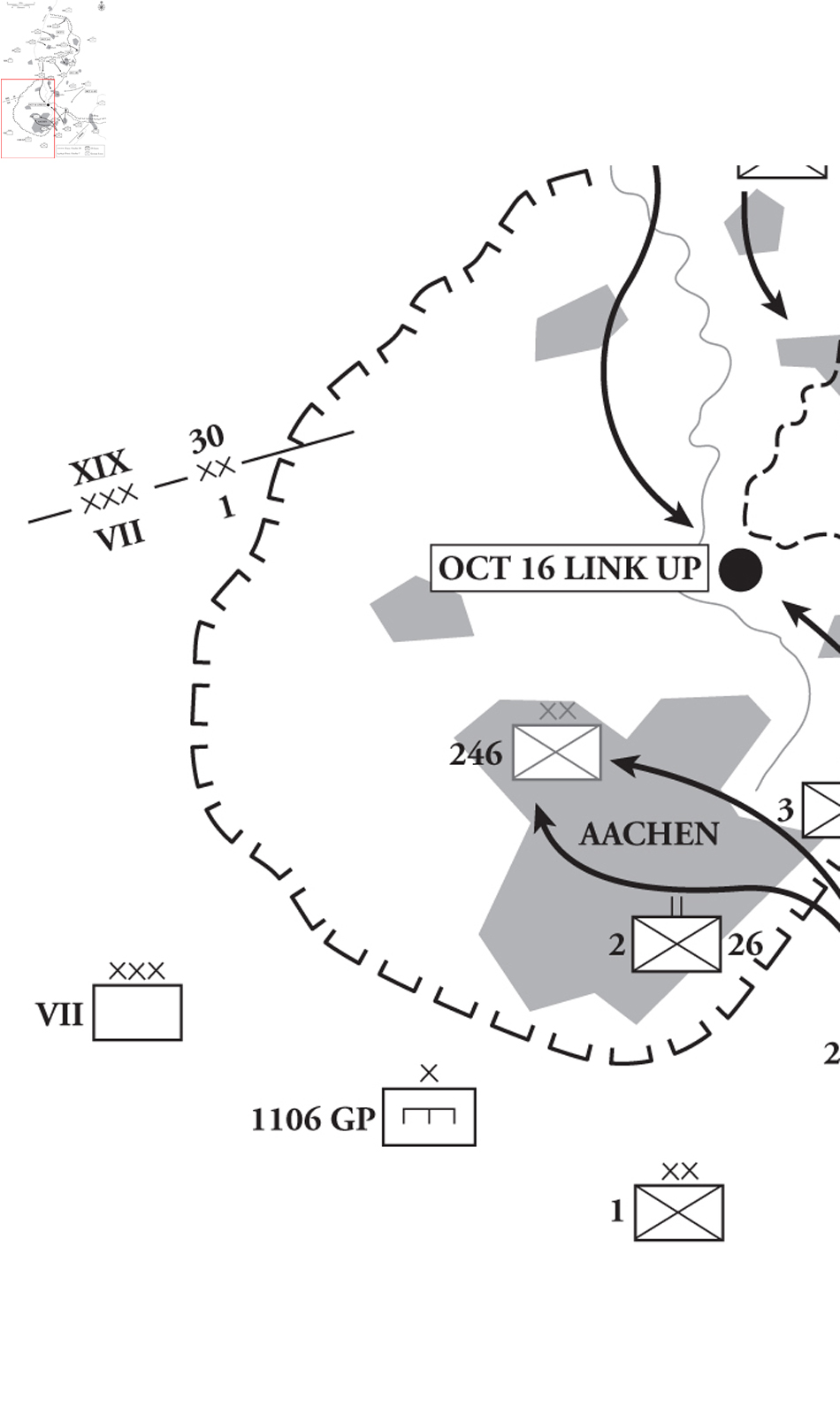

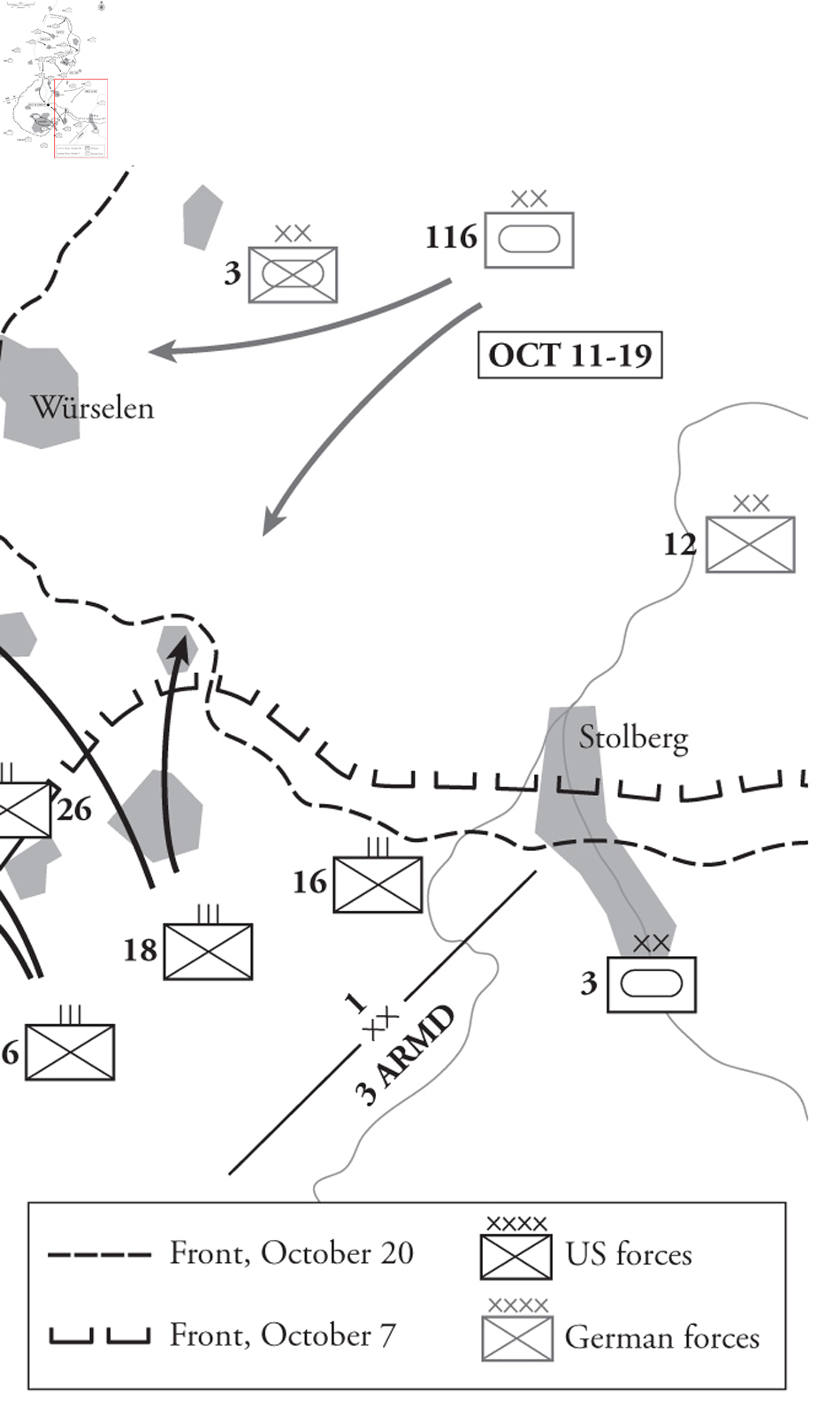

Map 3.1 The Battle for Aachen, October 1944

Meanwhile, the failed German counterattack left the German Seventh Army dangerously exposed to the American armored spearheads spreading out in all directions through the gap in the German lines. In orders reminiscent of Stalingrad, Hitler ordered that the German army not withdraw, and fight for every piece of French soil. This set up the German Seventh Army to be enveloped by elements of the US First and Third Armies which hooked north and east behind the Germans. Simultaneously the British launched an offensive on the opposite side of the front designed to envelop the Seventh Army from the north. As the Allied pincers began to close, the German command recognized the danger and belatedly began to withdraw. Though some of the German Seventh Army escaped the trap at the Falaise pocket, the bulk of it was destroyed and the American and British forces then turned and began to pursue the rapidly retreating Germans toward the German border.

By the middle of September the US Third Army was approaching the German fortress complex in Lorraine centered on the famous city of Metz. The US First Army liberated all of Northern France, Luxembourg, and southern Belgium and was approaching the German frontier defenses, known as the Siegfried Line, along the German–Belgium border. The British 21st Army Group had pursued the Germans north, liberating western Belgium and Antwerp. The British were poised to liberate Holland and cross the Rhine. It was at this point in the offensive, after seven weeks of continuous high-tempo offensive operations, that the bane of all senior commanders – logistics – began to dominate operational decision-making.

Though the breakout from the Normandy beachheads had been wildly successful, the Germans had managed to either defend or destroy virtually all the major port facilities along the French coast. Thus, the two Allied army groups, the 12th US Army Group and the British 21st Army Group, were both primarily reliant on logistics brought over the Normandy beaches. The volume of supplies that the Allies could move over the beaches was limited. Further, the French railroad system had been effectively destroyed by Allied airpower. Thus, most of what was brought ashore was moved forward by truck. There were simply not enough trucks for the job, and thousands of miles traveled quickly began to wear out the trucks that were available. Thus, by mid-September 1944, the Allied spearheads began to grind to a halt for lack of fuel. It was at this time that the leading combat elements of the US First Army reached Aachen, which was virtually undefended.

The supreme Allied commander, General Dwight Eisenhower, was acutely aware of the logistics problems. He also understood that the German army was in full retreat, that the western defenses of Germany were largely unmanned, and that there was an opportunity to possibly end the war before Christmas. Eisenhower had the logistics capability to sustain one of the three major axes being pursued by his armies, but the cost of doing so was stopping the other two offensives in their tracks. For a variety of valid, if arguable, reasons, Eisenhower determined to back his northern attack led by the British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. Offensive operations in the US 12th Army Group were suspended and the US First and Third Armies halted. The US forces in the vicinity of Aachen reverted to the defense.

The Aachen terrain corridor was a stretch of relatively open ground that could give large formations access into northern Germany. To the north of the Aachen area was Holland and that approach was characterized by numerous canals, estuaries, associated bridges, and marshes. It was not a promising approach for large mobile formations. South of Aachen lay the Hurtigen and the Ardennes forests. These dense forests lay over steep hills and ravines, had a very limited road network to the east, and thus were excellent for defensive operations and unsuited to large mobile operations. The next eastward avenue suitable for the movement of large mobile formations was far to the south in the Lorraine. It was in this area that Patton’s Third Army operated. Thus, the best approach route into Germany in the northern part of the front was through Aachen, and it was in the northern part of the front that the bulk of the Allied combat power lay.

Aachen had a special place in German history and in the ideological underpinnings of the Third Reich. Hitler declared the city a “festung” city, a fortress city, and that it was to be defended to the last. Toward this end the Nazi government evacuated most of the citizens as the US forces approached. When the initial impulse toward Aachen in September failed to take the city, the Nazi propaganda machine began to portray Aachen as a reverse Stalingrad. According to Nazi propaganda, the US Army would be lured into a battle for Aachen and destroyed.

The failure of Field Marshal Montgomery’s offensive to cross the Rhine in September – Operation Market Garden – is well documented. Less well known is what German officers on the Western Front came to call “the miracle in the West.” Warfare at all levels, tactical through strategic, is often a matter of simple choices which slow or speed a campaign or battle. Minutes, hours, and days often spell the difference between victory and defeat, or swift victory and slow destruction. The delay caused to the American advance by logistics problems, lasting through the last two weeks of September 1944, was the breathing space that the German command needed to reorganize units, bring forward supplies, and shuffle reinforcements to the west. Thus, at the end of September 1944, when the US armies were ready to resume their advance, they faced a much more formidable foe.

When offensive operations began again on the Western Front in October 1944, not only were the German forces no longer in full retreat, but General Eisenhower had adopted a new strategy for the front. Eisenhower determined that with the failure of Operation Market Garden any single thrust deep into Germany was too risky. Instead he adopted a broad-front strategy. Eisenhower’s concept – to attack simultaneously with all Allied armies from Holland to the Swiss border – was bold and insightful. It leveraged the Allies’ great advantage in resources, and somewhat mitigated any advantage the Germans may have had in tactical skill and equipment. Within the context of this broad-front strategy, General Courtney Hodges planned for his US First Army to resume offensive operations in early October. His initial major objective was the German city of Aachen, which lay on the tri-border point between Holland, Belgium, and Germany. Hodges’ concept was that the Aachen battle would penetrate the Siegfried Line, and open up the Ruhr industrial area to Allied occupation as a prelude to crossing the Rhine River.

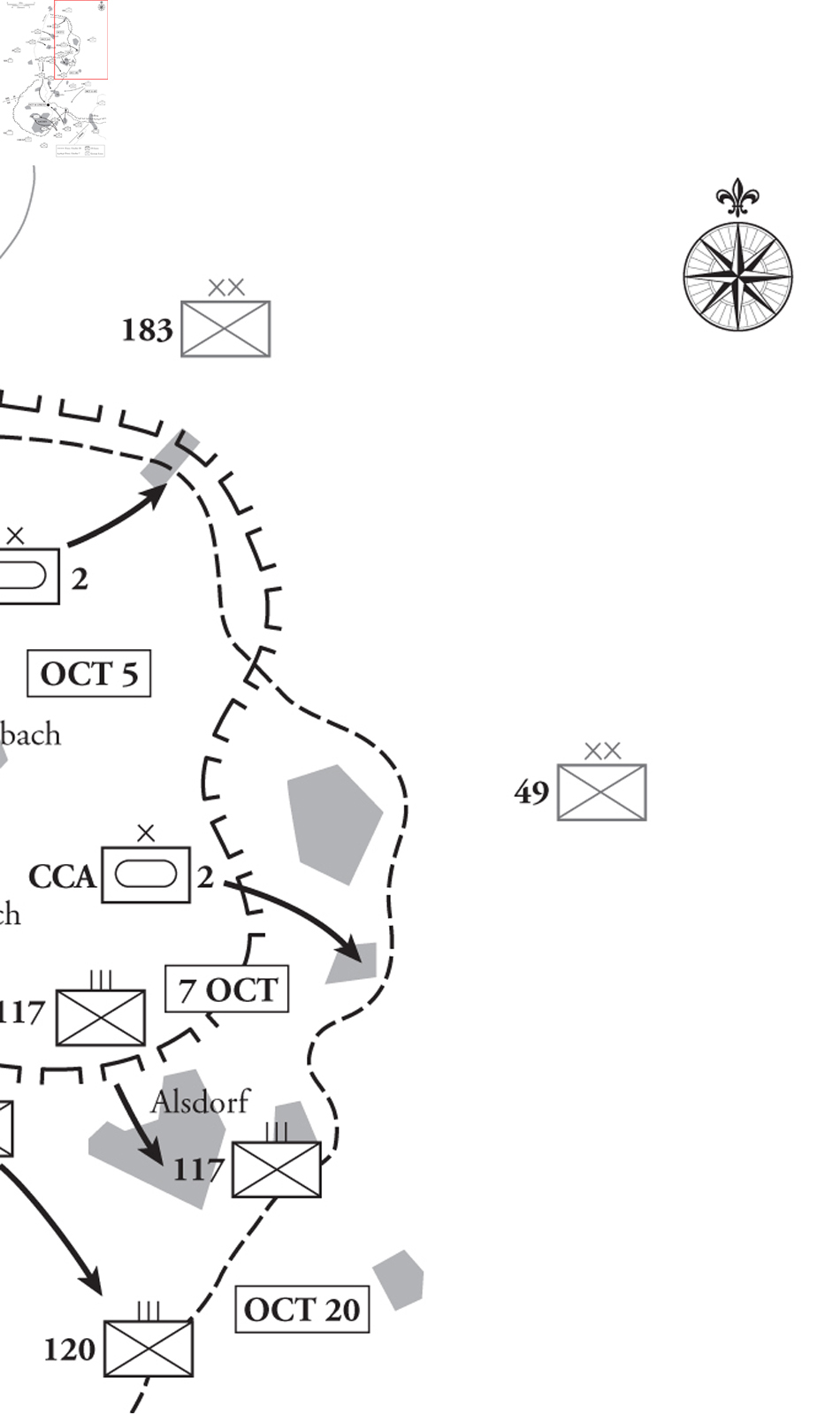

The approach to the Aachen, and the battle itself, was controlled directly by the US First Army. This was required because the Aachen sector of the front was split by a corps boundary. The XIX Corps was positioned north of Aachen while the southern portion and the main part of the city were in the zone of the VII Corps. The First Army plan to capture the city was relatively simple. The XIX Corps would attack north of the city and drive east and then southeast to encircle the city from the north. After success in the north, the VII Corps would launch its attack northeast to link up with the XIX Corps. Once the two corps had linked up and isolated the city, elements of VII Corps’ 1st Infantry Division would assault the city directly to capture it.

Aachen lay in the sector of the German LXXXI Corps, under General der Infanterie Friedrich Köchling. The corps was part of the rebuilt German Seventh Army, part of Army Group B under Field Marshal Walter Model who was tasked by Hitler with stabilizing the situation on the Western Front. The entire front was commanded by the venerable German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. Having staved off a coup de main seizure of the city in early September, the German command recognized that Aachen had to be held as long as possible for several reasons. First was the importance of the Siegfried Line defenses, two belts of which ran to the east and west of the city. Second, the political symbolism of an ancient German city resisting the Allied assault was extremely valuable propaganda. Finally – and this was a factor which influenced all German operations in the battle – the German counteroffensive planned for the west, Operation Wacht am Rhine, later known as the Battle of the Bulge, was to be launched out of the German Eifel Mountains into the Ardennes forest south of Aachen. A successful penetration at Aachen would place the Allies deep in the northern flank of this planned attack and make it very vulnerable to counterattack.

The German LXXXI Corps defended the Aachen sector with four infantry divisions: the 183rd and 49th Divisions; the 246th Division, which had responsibility for the city itself; and the 12th Division, which defended west of the city in the vicinity of Stolberg. The corps had a number of separate panzer and assault gun units in reserve, notably the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion, equipped with King Tiger tanks. The mission of these mobile forces was to counterattack against any penetration of the infantry division defensive lines. Available, but not released to the corps, was the Army Group B reserve of the 116th Panzer Division and the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, both organized under I SS Panzer Corps. Field Marshal von Rundstedt had control of the mobile reserve and would only release it under extreme circumstances.

In early September the German Seventh Army was in disarray and the West Wall defenses were largely unmanned. As the German army retreated, the German command assigned the defense of Aachen to the 116th Panzer Division. This unit, however, was only a shadow of itself after the losses of August. The German commander decided to give up Aachen without a fight. The American VII Corps, however, determined not to attack directly into the city and the 3rd Armored Division leading the corps advance bypassed Aachen to the south and advanced east and northeast beyond the city into the outskirts of the town of Stolberg. Elements of the 3rd Armored were positioned on the western edge of Stolberg when offensive operations ceased to permit priority of supplies to Market Garden in September. As September ended, the US First Army sat immobilized on the German frontier. The VII Corps’ 3rd Armored Division was positioned east of Aachen near Stolberg. The Corps’ 1st Infantry Division was positioned east and south of the city. The boundary between VII Corps and XIX Corps ran roughly through the western portion of the city. North of the city was the area of operations of the 30th Infantry Division whose front generally followed the Wurm River which flowed northwest from northern Aachen.

The battle for Aachen began on October 2, 1944, with the attack of the 30th Infantry Division across the Wurm River, north of Aachen. The American plan was simple, tactically sound, and reflected a solid understanding of urban warfare. The attack involved three divisions and supporting troops. In phase one of the attack, the 30th Division attacked north of the city to drive east and then southeast to secure the town of Wurselen, about 9 miles northeast of the city proper. The 2nd Armored Division supported the attack of the 30th and protected the 30th’s northern flank from counterattack. In the second phase of the attack, the 1st Infantry Division attacked from the south to the north to secure Aachen’s eastern suburbs and to link up with the 30th Division in Wurselen. Phase two’s objective was the complete isolation of the city. The final phase of the attack was an attack by two battalions of the 1st Division’s 26th Infantry Regiment. This attack was from east to west to capture the city center itself. Phase three was timed to occur after the completion of phase two.

At 9am on October 2, the US XIX Corps began its attack with a massive aerial bombardment of German positions, followed closely by an artillery attack which included 26 artillery battalions firing almost 20,000 rounds of ammunition. The 30th Division attacked with two regiments, the 117th and 119th, abreast. The regiments had to penetrate a line of West Wall pillboxes and bunkers, and then attack through a series of small but substantial towns en route to the division’s objective for linkup with VII Corps. Over a period of five days, October 2–7, the two infantry regiments, augmented by reinforcements from the division’s 120th Regiment, made slow but steady progress. The Germans opposed every step of the 30th Division’s advance and each successful American attack was met with a focused German counterattack. General Köchling, the commander of LXXXI Corps, supported by field marshals Model and von Rundstedt, used every available unit in the corps sector to attempt to stop and reverse the American advance. All three of the understrength assault-gun brigades in the corps were used to counterattack the Americans, including the heavy King Tiger tanks of the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion. Infantry battalions were withdrawn from both north and south of the 30th Division penetration to help contain the US attack. An entire infantry regiment and six powerful antitank guns were pulled from Aachen itself to reinforce the forces fighting the 30th Division attack. In addition, the Germans assembled massive amounts of artillery to continually pound the American forward positions and the Wurm River crossing sites.

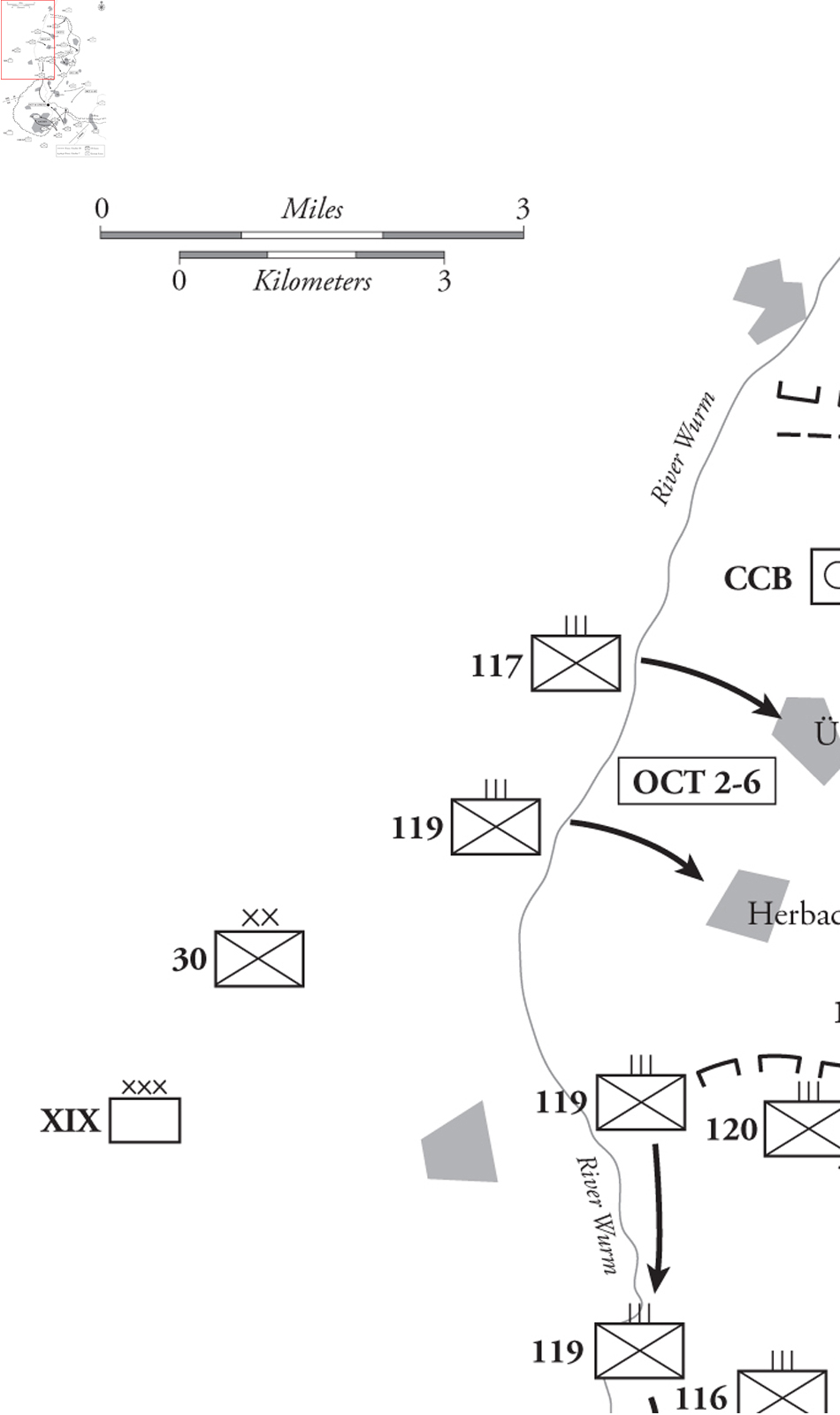

The Americans met each German counterattack, and the XIX Corps committed the 2nd Armored Division in support of the 30th Division in order to keep the 30th Division’s attack moving and to protect the lengthening north flank of the division. By October 7, the 30th Division had secured Alsdorf and the southern regiment was poised 3 miles from the objective of Wurselen. The German LXXXI Corps had expended all of its resources in its unsuccessful effort to stop XIX Corps’ attack. At that point in the battle the US VII Corps launched its attack.

By October 7, most of the German LXXXI Corps’ reserves were fully committed to the battle. This included all of the mobile elements from the assault-gun brigades, the 108th Panzer Brigade, and the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion. These were impressive formations on paper, but only actually fielded 22 assault guns, four heavy Mark VI (Tiger) tanks, and seven medium Mark V (Panther) tanks. Not an inconsequential force, but only a fraction of what the unit titles represented. It was roughly the size of a weak American armored combat command. On October 5, von Rundstedt released his theater reserves, the rebuilt 116th Panzer Division and the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, both divisions under command of the I SS Panzer Corps headquarters, to enter the Aachen battle. The panzer division, though not at full strength, was equipped with 41 Mark IV and V medium tanks. Both divisions had their full complement of infantry, artillery, and antitank guns. It was a significant counterattack force but would take several days to enter the battle.

On October 7, the VII Corps’ 1st Infantry Division occupied positions on the west, south, and east sides of Aachen. The Germans were supplying the city garrison along two highways which entered the city from the north. When the 30th Division captured Alsdorf on October 7 they captured one of the two highways leading into Aachen, leaving the German LXXXI Corps a single line of communications and supply into the city. The 1st Infantry Division was arrayed with all three of its regiments on line over a 12-mile front. From east to west the regiments of the division were aligned with the 16th Infantry Regiment west of Stolberg, the 18th Regiment in the suburbs just east of Aachen proper, and the 26th Regiment bending the line south along the perimeter of the city. The 1st Division’s line was filled south and west of the city by 1106th Combat Engineer Group whose engineer battalions were in the line occupying foxholes as infantry.

In the darkness of the morning of October 8, the 18th Regiment spearheaded the 1st Division’s attack to complete the encirclement of Aachen. The 16th Regiment would guard the flank of the 18th Regiment and link the division to the 3rd Armored Division defending further east in Stolberg. The 26th Regiment’s 1st and 2nd battalions would remain in position facing downtown Aachen. The 18th Regiment’s objective was a series of three hills which dominated the approach into Aachen. The attacking companies were led by special assault squads armed with flamethrowers, bangalore torpedoes, and explosive satchel charges, and specifically trained to attack German pillboxes and bunkers. In addition, a company of mobile tank destroyers and a battery of self-propelled artillery guns supported the regiment by taking the bunkers under direct fire as the assault teams closed in. Eleven artillery battalions fired in support of the assault. In 48 hours the regiment succeeded in taking all of its objectives with very few casualties. The assault teams, supported by fire from tanks, tank destroyers and direct fire artillery, closed in on the bunkers under the protection of a heavy artillery barrage. As soon as the artillery lifted, the bunkers were attacked before the defenders could recover. In this manner the first two objectives were taken. The final hill was captured by a night assault during which the US infantry infiltrated around the German bunkers and occupied the crest of the hill in darkness. The next morning the Americans mopped up the German positions from the rear. By October 10, the 18th Regiment was firmly in position north of Aachen and awaiting the linkup with 30th Division attacking south from the north. The attacks of the 1st Infantry Division left only one narrow corridor into Aachen in German hands. As the 18th Regiment consolidated its new positions, the Germans ordered the theater reserves, the 116th Panzer Division and 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, to counterattack at Aachen.

The German reserves began positioning for their counterattack on October 10. The first attack took place on that day against the 30th Division, and included elements of the 116th Panzer. By October 15, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier was in position to attack. The attack came early in the morning and was not aimed directly at the 18th Regiment but further east, at the left flank of the 16th Regiment which had not participated in the attack to close the circle and was therefore rested and in good defensive positions. The Germans attacked in the early morning with two Panzer Grenadier regiments supported by 10–15 Tiger tanks against a single US infantry battalion of the 16th Regiment. However, the Americans were prepared and as the German infantry advanced across open ground, six American artillery battalions laid down a preplanned barrage on the exposed infantry. The artillery stopped the German infantry but the Tiger tanks rolled into the American positions and began firing on the foxholes from point-blank range. American artillery continued to pour into the German attackers as well as work back into the supporting positions preventing reinforcement and the bringing forward of supplies and ammunition. The US artillery also fired on several of its own company positions, while the infantry hugged the bottom of their foxholes, to prevent the Germans from overrunning the battalion. Air support arrived in the form of a squadron of P-47 fighter bombers in the early afternoon. The aircraft strafed the exposed German troops and finally broke the German attack. Though the American infantry could do little to stop the German tanks, the American artillery completely demolished the German infantry attacks and the German tanks were loath to advance without infantry support. That night the Germans attacked again with the same result. The attacks were broken up by heavy artillery fire even as they reached the US positions and the infantry fought hand to hand. By October 16, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier division had lost a third of its strength in attacking the lone US battalion and withdrew to regroup. Thus ended the most dangerous threat to the eastern US positions.

As the 1st Infantry Division attacked and then defended against the German counterattack, the 30th Division began its attack south from Alsdorf to link up with the 1st Division. The division attacked with all three regiments on line. The 117th Regiment in the north attacked to further establish the northern flank and protect the regiments further south. The 120th Regiment in the center attacked to secure high ground northeast of Wurselen and thus dominate approaches to the town from the north and east. The attack of the 120th would support the attack of the 119th Regiment which would attack southeast into the northern part of Wurselen, the division objective. Control of Wurselen would effectively close the last route into Aachen and put the 30th Division approximately a mile from the westernmost element of the 1st Division’s 18th Regiment. Patrols would seal the linkup and close off German access to Aachen.

The attack to link up began inauspiciously on October 8 when the northern 117th Regiment attacked headlong into the German counterattack made by Mobile Group von Fritzschen, a hastily assembled but potent organization formed by LXXXI Corps around the 108th Panzer Brigade. The German force included numerous halftracks, several infantry battalions, Panzer IVs and Vs of the brigade, and Tiger tanks of the ubiquitous 506th Heavy Tank battalion. The objective of the mobile group was to recapture Alsdorf. Though the Germans were beaten back with severe losses by the 117th Regiment, they were successful in stopping the attack of the 117th Regiment. During the night the German infantry reverted to the defense, the 506th Tiger tanks moved south to join the attack against the 1st Infantry Division on the opposite side of Aachen, and the 108th Panzer Brigade moved south to continue the attack to expand the corridor into Aachen. On October 9, the 108th Panzer Brigade attacked again but ran into the attack of the 120th Infantry Regiment in the center of the 30th Division line. The Germans successfully blocked the American attack and seized the town of Bardenberg.

The German attack that seized Bardenberg on October 9 caused great concern in the 30th Division because it effectively isolated two battalions of the 119th Infantry Regiment which had previously secured the northern portion of the division’s objective, Wurselen. On October 10, the 119th Infantry attacked to retake Bardenberg but were unsuccessful in a daylong fight with German panzers and halftracks in the town. Meanwhile the 120th Regiment captured the road leading into the town, effectively isolating the German forces. At night the Americans withdrew from the edges of Bardenberg to allow American artillery to bombard the town. The next day a fresh American infantry battalion attacked the town and in a daylong fight captured it, in the process destroying 16 German halftracks and six tanks. The fighting in Bardenberg absorbed all of the reserves of the 30th Division and on the same day division intelligence reported identifying elements of the 116th Panzer Division in the area. General Leland S. Hobbs was justifiably concerned with his division completely committed, no reserves, soldiers tired after ten days of continuous offensive operations, and a fresh German panzer division in the area. The general ordered his center and northern regiments to halt and defend, and determined to focus the division’s efforts on the attack to secure the primary objective at Wurselen.

On the morning of October 12, the 30th Division’s attack on Wurselen had not even begun when another German counterattack hit the division. This attack was led by the panzergrenadier regiment of the 116th Panzer Division, but also included an infantry battalion of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division in Aachen, elements of the 1st SS Panzer Division (Kampfgruppe Diefenthal), remnants of 108th Panzer Brigade, and Tiger tanks of the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion, all under the control of the I SS Panzer Corps which took over responsibility of the northern German defense against the 30th Infantry Division from the LXXXI Corps. Indications to the US XIX Corps commander, General Charles H. Corlett, were that the 30th Division might be fighting two panzer divisions. All throughout October 12, the regiments of the 30th Division successfully fended off the German attacks with the help of supporting artillery and fighter-bombers.

The 30th Division resumed the attack through Wurselen on October 13 and made only very limited progress for three days. The town was defended by the 60th Panzergrenadier Regiment of the 116th Panzer Division supported by the division reconnaissance battalion and the engineer battalion as well as numerous small detachments of panzers. The American attack was on such a narrow front that the German defensive concentration was very effective and in three days the Americans barely advanced 1,000 yards. Frustrated with the slow pace of the attack through Wurselen, on October 16 the 30th Division opened a new attack, this time along the banks of the Wurm River. The attack, aided by diversions all along the 30th Division line, made rapid progress and at 4.15pm a patrol from the 119th Regiment linked up with the 1st Infantry Division, isolating the German garrison in Aachen.

For most of the time that the two-week battle over access to Aachen raged around the city, things inside the city were relatively quiet. As the Germans and Americans traded attack and counterattack outside the city, over 5,000 defenders of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division under Colonel Gerhardt Wilck waited in the center of the city for the American assault. Wilck’s force was almost entirely infantry but he did have other arms to assist in the defense including five Mark IV tanks, and over 30 artillery pieces. In addition he had access to several battalions of artillery support outside of the city. Wilck’s infantry varied greatly in quality. They included fortress garrison units and policemen who possessed minimum combat skills, as well as a company of German paratroopers and a battalion of SS panzergrenadiers. The latter two organizations were the best infantry found in the German army. Wilck’s force had ample time to set up their defense and was not surprised when the Americans began their attack.

The American forces designated for the attack into Aachen were the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. On October 10, as the 30th Division began to make what was thought to be a quick attack to link up with the 1st Division and complete the isolation of the city, the VII Corps commander ordered that the city garrison be given a surrender ultimatum. This document, issued by General Clarence Huebner, commander of the 1st Division, promised the destruction of the city if it was not surrendered within 24 hours. On October 11, the time in the American ultimatum passed and US artillery bombardment and air strikes on the city commenced. For an entire day the bombardment continued, with over 100 guns firing over 500 tons of ammunition into the city. On October 12, the attack on the city center commenced with the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry (3/26) attacking on the right, and the following day the 2nd Battalion (2/26) attacked on the left. The objective of 3/26 was to cover the right flank of 2/26 and clear the industrial areas on the north side of the city. The 2/26 had the mission of attacking straight into the heart of the city center across a significant frontage of 2,000 yards filled with destroyed and partly destroyed buildings, each of which had to be cleared by the infantry. It would be a slow, systematic attack.

Prior to beginning the attack, the American commanders analyzed the situation and identified four challenges: high ammunition expenditures; command and control; thousands of civilians in the combat zone; and maximizing armor support without losing too many tanks. The ammunition problem was solved by building up battalion ammunition caches close to the assault positions so that resupply would be readily available during the attack. The command and control problem was solved by developing a specific map code where each major building and street intersection was assigned a unique code so that units could provide quick pinpoint information regarding where they were and where they needed artillery fire. The problem of civilians was answered by deciding to evacuate the entire civilian population as the units advanced through the city. This solved multiple problems: it prevented enemy combatants from hiding within the civilian population; it reduced the attacking unit’s administrative burden of dealing with the population; it reduced the possibility of the population interfering with operations; and it provided maximum protection to the population once they came under American control. The attackers planned to reduce the vulnerabilities of the American tanks by minimizing the exposure of the tanks on the major city streets. The idea was to move the tanks down side streets whenever possible, keep the infantry in close proximity of the tanks, use buildings as cover for the tanks whenever possible (firing around building corners), and finally, suppressing all enemy positions by fire whenever the tanks had to move from one firing position to another.

The Americans also adjusted their combat organization specifically for the fight in the city. In 2/26, which planned for the attack into the city central, the commander reorganized his battalion to create three self-contained assault companies. The battalion broke up its heavy weapons company and was reinforced with antitank guns from the regiment’s antitank company, and distributed these capabilities among the three infantry rifle companies: each company was provided with two additional 57mm antitank cannons, two heavy machine guns, two bazooka teams, and a flamethrower. The battalion’s attached armored support was likewise distributed among the assault companies: each company was assigned three tanks or self-propelled tank destroyers, which were then allocated, one to each of the company’s platoons. The battalion planned to attack with all three companies and no reserve. Any reserve would have to be provided by higher headquarters.

The attack technique of the American battalions going into Aachen was represented by the philosophy of 2/26 commander, Lieutenant Colonel Derrill Daniel, who told his subordinates to “knock them all down.” The basic philosophy of the battalion was to use firepower to destroy the enemy before they had to clear buildings and engage in a short-range infantry fight. Collateral damage to buildings was not a consideration in the fight, and civilian casualties were only a secondary consideration. The Americans were perfectly content to knock a building down on top of its defenders if that prevented American casualties.

By October 15, three days after beginning the assault, the two American battalions in the attack had battered their way deep into the city. American infantry avoided the streets and instead burrowed their way from building to adjacent building through the building or basement walls. American armor moved steadily down the streets but only stopped in areas protected by buildings and within a surrounding screen of American infantry support. German handheld antitank weapons, panzerfausts, were very effective against the unwary tank that exposed itself. The Americans found that many German bunkers, and even some buildings, were relatively impervious to the tank fire supporting the infantry. To increase the fire support to the infantry, both American battalions brought forward 155mm self-propelled artillery guns. These proved to be incredible psychological weapons as well as being capable of bringing down a multistory apartment building with a single round. In some cases just the threat of using the artillery gun on a position was sufficient to induce the Germans to surrender.

Offensive operations inside the city were delayed on October 15 as the 1st Division confronted the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division counterattack. On October 16, the 30th and 1st Infantry Divisions isolated the city. The attack resumed again on October 18, in the pattern that existed before. The two American battalions methodically moved from objective to objective using a combination of artillery, mortar, machine-gun, and tank fire to suppress the Germans prior to a rapid infantry assault. Both battalions were unhurried in their operations and took time to methodically clear each objective as it was won. This included clearing underground sewer systems and conducting room-to-room searches for enemy who had remained behind. The 26th Infantry was joined in the Aachen battle by a two-battalion task force of the 3rd Armored Division attacking on the north flank of the 3/26 Infantry, and a single battalion of the 28th Infantry Division filling the growing gap between the advancing 2/26 and the 1106th Engineer Group. On October 18 and 19 the relentless advance continued, block by block, objective by objective. On the 19th the German defenses began to crumble as the German troops recognized the inevitable end and surrenders increased dramatically. By October 20 the city center and the northern zone of the city had been taken and the pace of the American attack increased. The only remaining resistance existed in the western and southwestern suburbs, areas low on the Americans’ priority list of objectives. Finally, on October 21, Colonel Wilck, against Hitler’s orders to resist, surrendered his headquarters and all German troops under his command, just prior to an assault by 3/26.

The US Army took 19 days to capture Aachen and its 20,000 remaining inhabitants. The 30th and the 1st US Infantry Divisions captured approximately 12,000 prisoners. Though no accurate count of German casualties was possible, they were certainly in the area of 15,000 in addition to those taken prisoner – casualties in the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division alone were at least 3,000. Over 20 different German infantry and panzer battalions were used in futile counterattacks to retake lost ground and push the Americans back across the Wurm River. During the battle the US artillery fired an average of 9,300 artillery rounds a day and the Germans were estimated to have used 4,500 rounds a day. American losses were significant: the 30th Division suffered approximately 3,000 casualties in 19 days of combat, roughly 20 percent of the division strength but almost a third of the division’s infantry strength. Aachen was an important battle in which, ironically, both sides achieved their objectives. The Germans had managed to keep the Americans from capturing the city for almost three weeks, until nearly the end of October, and protected their ability to stage for the coming counteroffensive – the Battle of the Bulge. The Americans were able to take the city, breach the West Wall, and secure a start position for their final offensive into Germany and across the Rhine River.

Aachen demonstrated and validated many important lessons regarding conventional urban combat. Many of the issues illustrated at Aachen were identical to characteristics of urban warfare highlighted in the earlier Stalingrad battle. Aachen validated the important role of the fight outside the city to the fight inside the city; like Stalingrad, the decisive operations occurred well outside the city, making the final reduction of the city center somewhat anticlimactic. The battle validated the critical role of armor in urban warfare – tanks were a key element in all operations. The US infantry always attacked with tank support. The only serious threats to US domination of the battlefield came from the various German armor units thrust into the battle by the German LXXXI Corps. The Tiger tanks of the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion were a dangerous nemesis. The most serious German counterattacks against the American attack were by the mobile formations of the I SS Panzer Corps.

Aachen also illustrated the continued necessity for tailoring unit organizations for urban combat at the lowest levels. The squad-level bunker-assault teams, and the combined-arms task forces built on the infantry companies of 2/26 were good representations of the benefits of building units tailored for the battle before the battle. Like the Germans and Soviets on the Eastern Front, the Americans understood that combined-arms assault teams were the required organization for urban combat. In Aachen the US infantry platoons advanced from one building to the next only after a preparatory barrage of artillery or mortars. The infantrymen led, supported closely by flamethrowers and tanks. The entire force avoided the open streets as much as possible. An important concern was not fretting away the numbers of the assault platoons by requiring them to occupy and guard the houses they captured. Other supporting arms, antitank guns, machine-gun crews, and even headquarters personnel, were dropped off by the advancing assault troops to guard captured buildings against reoccupation by the Germans.

Aachen confirmed the critical role of artillery in urban combat. The experienced American infantry assaulted defended positions close behind their supporting artillery barrage. A well-timed artillery attack did not kill many defenders but it allowed the attackers to close in on the building or bunker and assault it while the defenders sheltered from the barrage. American artillery, unlike Soviet artillery, and to a much greater degree than German, was responsive to forward observers and could quickly mass fire at any designated point within range. Thus, even small-scale assaults could be preceded by accurate artillery barrages. Aachen also demonstrated the fantastic effects that artillery in a direct-fire role could achieve. The employment of the self-propelled 155mm guns in support of the infantry demonstrated that those effects were not only material but psychological.

Aachen validated several characteristics of urban warfare which were valid regardless of what army was participating in the battle. These included the need for tanks, the requirement to use small combined-arms assault teams, the amount of time necessary to capture a city from a skilled and determined enemy, and the important role of the battles outside the city to ensure success inside the city. It also identified some aspects of urban warfare which were unique to American forces. American forces tended to substitute firepower for manpower, and though they did not change their operating methods, they did make plans for the civilian population even though it was considered hostile.

One of the uniquely American characteristics was the substitution whenever possible of firepower for manpower. The US forces made liberal use of artillery and airpower whenever possible. This permitted the Americans to conduct very intensive offensive operations without a major numerical advantage in infantry. Although American infantry did not outnumber their adversary, they made up for numerical parity with lavish quantities of artillery and airpower and virtually limitless supplies of munitions. This not only reduced the number of infantry required, it also reduced the number of casualties incurred by the attacking force.

The liberal use of firepower by the Americans would also seem to equate to a disregard for civilian casualties equivalent to the attitudes of the Germans and Soviets on the Eastern Front, but this was not the case. Though the Americans did not change their operational approach to account for civilian casualties, they made a major effort to remove civilians from the battle area once they came under American control. Civil Affairs specialists were positioned immediately behind the battle area to take charge of the civilian population, process it, and evacuate the population to camps under army control. Thus, though US forces in Aachen placed concern for enemy civilian casualties as a lower priority than mission accomplishment, it was still a priority of the command.

When the 26th Infantry Regiment assaulted Aachen on October 13, the two infantry battalions in the attack were outnumbered by Colonel Wilck’s defenders at least three to one. Despite all the advantages that the Americans had in airpower, the odds on the ground should have favored the German defense. That the American infantry were successful, and at a relatively low cost in casualties, was astounding. The success of the attack can be attributed to the application of a variety of urban fighting techniques, blended in a near-perfect combination by the soldiers of the US 2nd Armored Division, and 30th and 1st Infantry Divisions with their supporting units. Aachen demonstrated that it was very possible to capture a relatively large urban area, heavily defended by good-quality troops, with a comparatively small number of infantry.

The major difference between the American approach to Aachen and the German approach to Stalingrad was the use of maneuver to set favorable conditions for urban battle. The Americans fought and maneuvered outside of the city to isolate the city from support before reducing it. This greatly reduced the burden on the battalions that eventually assaulted the city center. Because the city was isolated, the Americans could choose to attack the city from any number of directions. In contrast, the Germans had to defend everywhere. Because the city was isolated, the Americans could attack the city from the east, when the city’s defenses were designed to protect from attacks from the west. Finally, because the city was isolated, the psychological stress on the defenders was significantly greater than on the attackers. These were all advantages that the Americans had at Aachen, and that the Germans did not have at Stalingrad. This aspect of the American approach to Aachen demonstrated the ideal operational conditions for city fighting: don’t fight for the city until you control access to the city. Despite the simplicity of this concept, subsequent chapters will show that its application is not always obvious to modern armies, or easy for them to achieve.