After World War II the American military jettisoned the vast bulk of the superb ground force that had fought and won the war. By 1950 that force was a hollow shell of its former self. The only remaining remnants of the combat-experienced ground forces were the non-commissioned officer and officer leadership of the skeleton divisions that remained in the force. The bulk of the force in 1950 was draftees with no experience, and in some cases their equipment wasn’t even the best of the World War II equipment. In the late summer of 1950, this force found itself in the midst of another large-scale urban battle against a wholly unanticipated foe in a theater of operations that many Americans had never heard of and would have a hard time finding on a map.

In June 1950 the forces of Communist North Korea launched a surprise attack on the forces of South Korea. The military forces of the North, well trained and equipped by the Soviet Union, vastly outnumbered those of the South. In addition, though there were US Army advisors with the Republic of Korea’s (ROK) military, the US vision for the ROK Army (ROKA) was as a large military police force; which meant that there were no heavy weapons, tanks, heavy artillery or antitank weapons among the small South Korean force. Because of this, and the surprise of the attack, the North Korea People’s Army (KPA) was very successful, and in just six weeks managed to push the combined South Korean and American defenders back to a small perimeter at the toe of Korea around the important port city of Pusan.

At the end of the first week of the surprise attack, the US military entered the war decisively on the side of South Korea. The most effective and responsive weapon that the US had in Asia was the US Air Force, and air attacks against the advancing North Korean columns began on June 27. However, air attacks could slow, but not stop the North Korean advance. Therefore, the US Eighth Army, stationed in Japan, began to deploy to Korea. The problem was that the Eighth Army in 1950 was a shadow of the great American army that had fought its way across the Pacific Ocean under General Douglas MacArthur during World War II. Still under MacArthur’s command – MacArthur was the Supreme Commander Allied Powers in Japan, and Commander US Forces Far East – the Eighth Army was greatly debilitated by post-World War II defense cuts. The Eighth Army had four divisions organized into two corps. However, each of the army’s infantry divisions comprised only two regiments instead of the doctrinal three. Likewise, each regiment had only two battalions, and each battalion only two companies. Similarly, division artillery was reduced to two battalions, all the medium and heavy artillery had been removed from the force at all levels, and each battalion only had two firing batteries of light howitzers. The medium-tank battalions supporting each infantry division was similarly reduced to light-tank battalions of only two companies each. Finally, if the numbers alone were not bad enough, budget and facility constraints greatly inhibited training, leaving the units in a poor state of readiness. Though a formidable force on paper, the Eighth Army and all its subordinate forces were in reality only about 50 percent as capable as the World War II version of the army. This army was thrown as fast as possible into the path of the advancing North Koreans.

General Walton Walker commanded the combined US and South Korean armies on the peninsula. In the last weeks of August 1950 he managed to stem the North Korean onslaught around the city of Pusan. However, in the first eight weeks of the war the Communists captured over 80 percent of the land of South Korea. Clearly, Walker and his commander, General Douglas MacArthur, could not sit passively on the defensive. As early as the end of July, as Walker fought desperately to maintain a toehold in Korea, General MacArthur was thinking in terms of a counterstroke.

MacArthur, in keeping with the operational thinking he had developed during the Pacific campaign of World War II, was keen to avoid the hard campaign that a counterattack back up the mountainous Korean peninsula would entail. He set his staff to investigating the various possibilities of an amphibious operation to bypass the major North Korean forces and land in their rear. This would avoid the tremendous casualties of a frontal assault, save invaluable time, and guarantee the complete destruction of the bulk of the North Korean army. The only problem was there was no suitable landing site for a major amphibious thrust along Korea’s very formidable coastline. The closest that the planners could identify was the city of Inchon on Korea’s west coast.

The command faced several significant problems executing a major amphibious assault at Inchon. These included the difficulty of the local tides, lack of suitable beaches, the difficulty of achieving surprise, and a shortage of trained troops available. MacArthur carefully considered the problems but also weighed the points in Inchon’s favor. The difficulty of the operation would lend itself to surprise and thus lessen opposition to the landing. Inchon’s geographic position put it close to Seoul. Thus, a successful landing at Inchon could easily lead to a quick conquest of Seoul. Seoul was MacArthur’s ultimate objective. The city’s geographic location put it astride the only important north–south maneuver corridor on the peninsula. Control of Seoul meant control of South Korea. More important than its position, which was extremely important, was that Seoul was also the capital city of South Korea. To many, the loss of Seoul had represented losing the war in the first week: recapturing Seoul represented snatching victory from apparent defeat. MacArthur recognized that the political and psychological importance of Seoul were beyond measure. MacArthur understood that the value of Seoul outweighed the operational risks inherent in an amphibious assault and therefore determined that the operation proceed over the objections of key subordinates and experts on amphibious operations.

To execute the operation to capture Seoul the Americans assembled a new unit, separate from the US Eighth Army fighting the battle at Pusan. This new unit, X Corps, was tailored for the amphibious operation, and reported not to Eighth Army, but directly to General MacArthur’s Far East Command. The two major subcomponents of the X Corps were the 1st US Marine Division, and the US Army 7th Infantry Division, all under the X Corps commander, Major General Edward Almond. In addition to the two infantry divisions, the corps had the direct support of the Marine Air Wing of the 1st Marine Division. It also included two ROK military units: the ROK Marine Regiment attached to the 1st Marine Division, and the ROK 1st Infantry Regiment attached to the 7th Infantry Division. These latter two units were critical for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was to improve the flagging prestige and morale of the ROK military, and also to highlight the important political objectives which were an important goal of the operation.

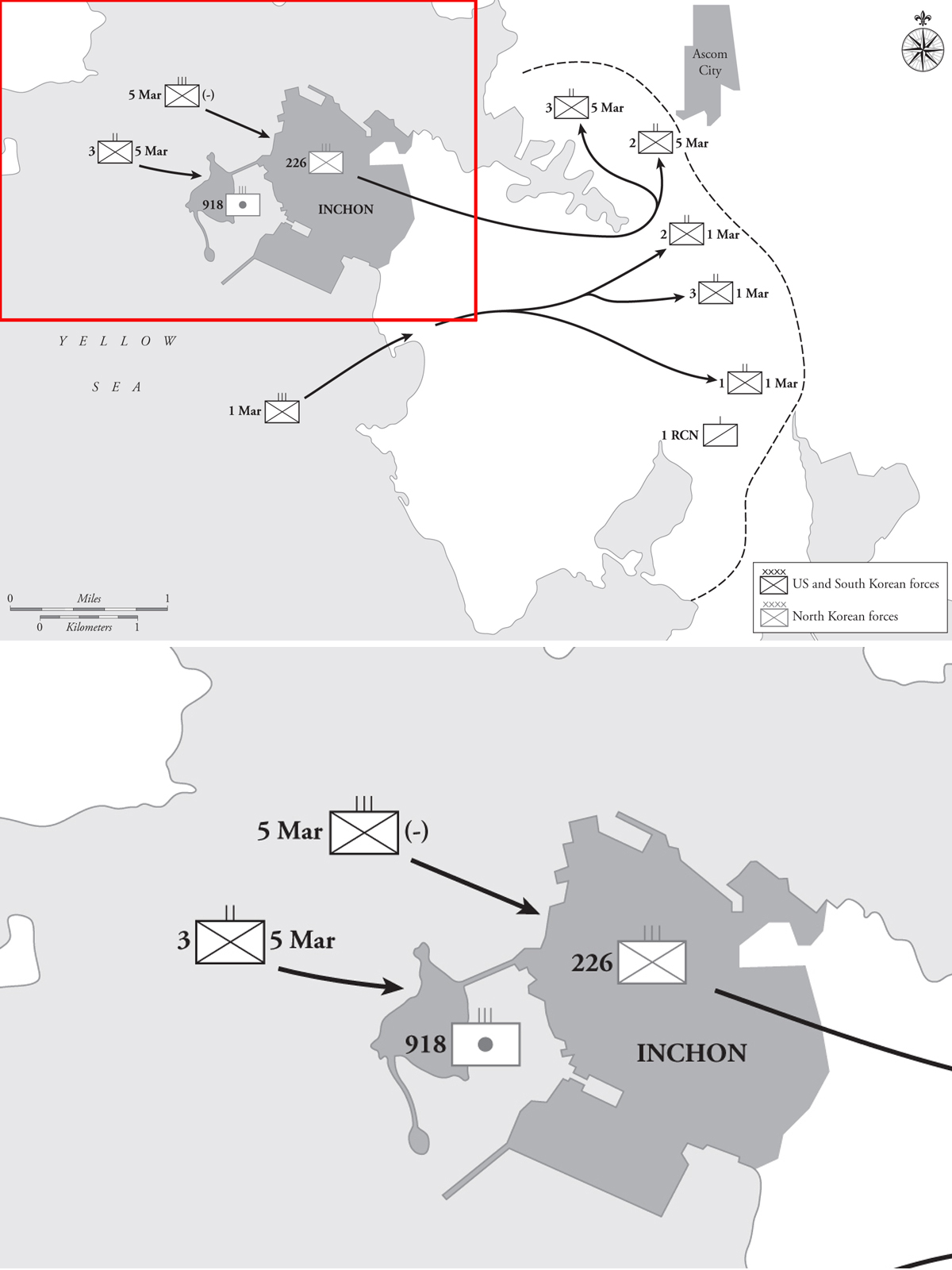

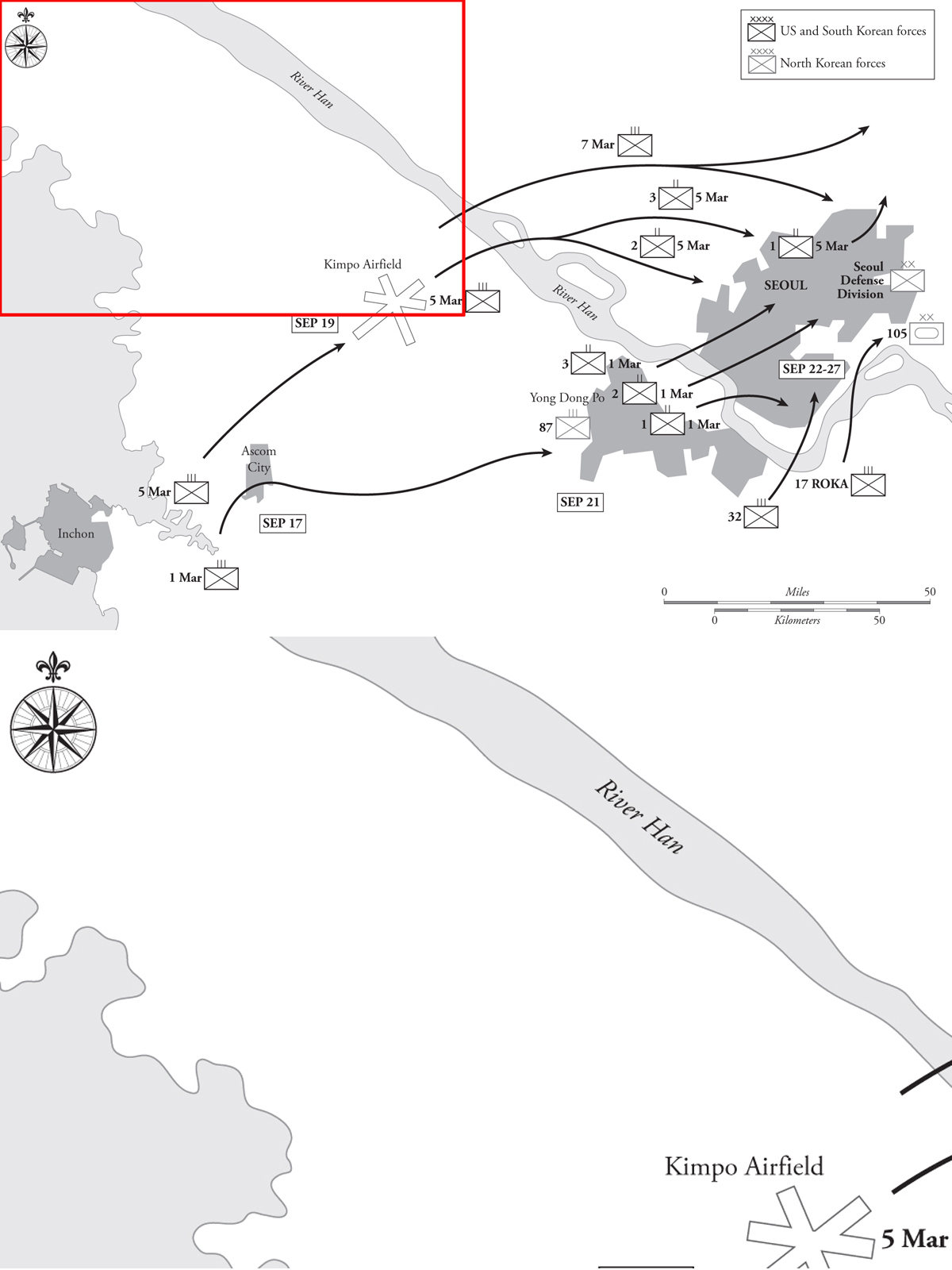

Map 4.1 The Inchon Landings, September 1950

Seoul was a city of over a million people when the war broke out – the fifth largest urban population in Asia. It was the ancient capital of the Korean peninsula and thus was extremely important to both North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – DPRK) and to South Korea. As the North Korean forces poured across the border in the summer of 1950, the population had panicked and attempted to flee. However, over a million people – largely without automotive transportation – cannot quickly pick up and move. So, as the Americans began to execute operations to recapture the capital, there were hundreds of thousands of South Korean civilians still living in Seoul under the occupation rule of North Korea.

The initial landing area at Inchon was opposed by about 2,000 troops. The KPA had a total of about 16,000 troops in the Inchon–Seoul area. This was a relatively light defensive force given the area’s strategic importance, but it reflected the North Korean high command’s focus on the battles in the south around the Pusan perimeter. In addition to the 2,000 troops positioned in the area of Inchon, another 2,000 troops of the 87th Infantry Regiment were positioned to defend the major suburb of Seoul at Yongdungpo. Additionally, Seoul was garrisoned and defended by the Seoul Defense Division, a unit of approximately 10,000 troops. The remainder of the initial KPA forces around the capital were various support units. Not part of the Seoul garrison, but able to respond quickly to any threat to the city or an amphibious landing, was the KPA’s theater reserve, the 105th Tank Division, equipped with T-34/85 tanks. This unit was the premier unit of the KPA, equipped with over 50 tanks, supporting artillery, and antitank and infantry subunits. It was refitting near Seoul when the landings at Inchon occurred.

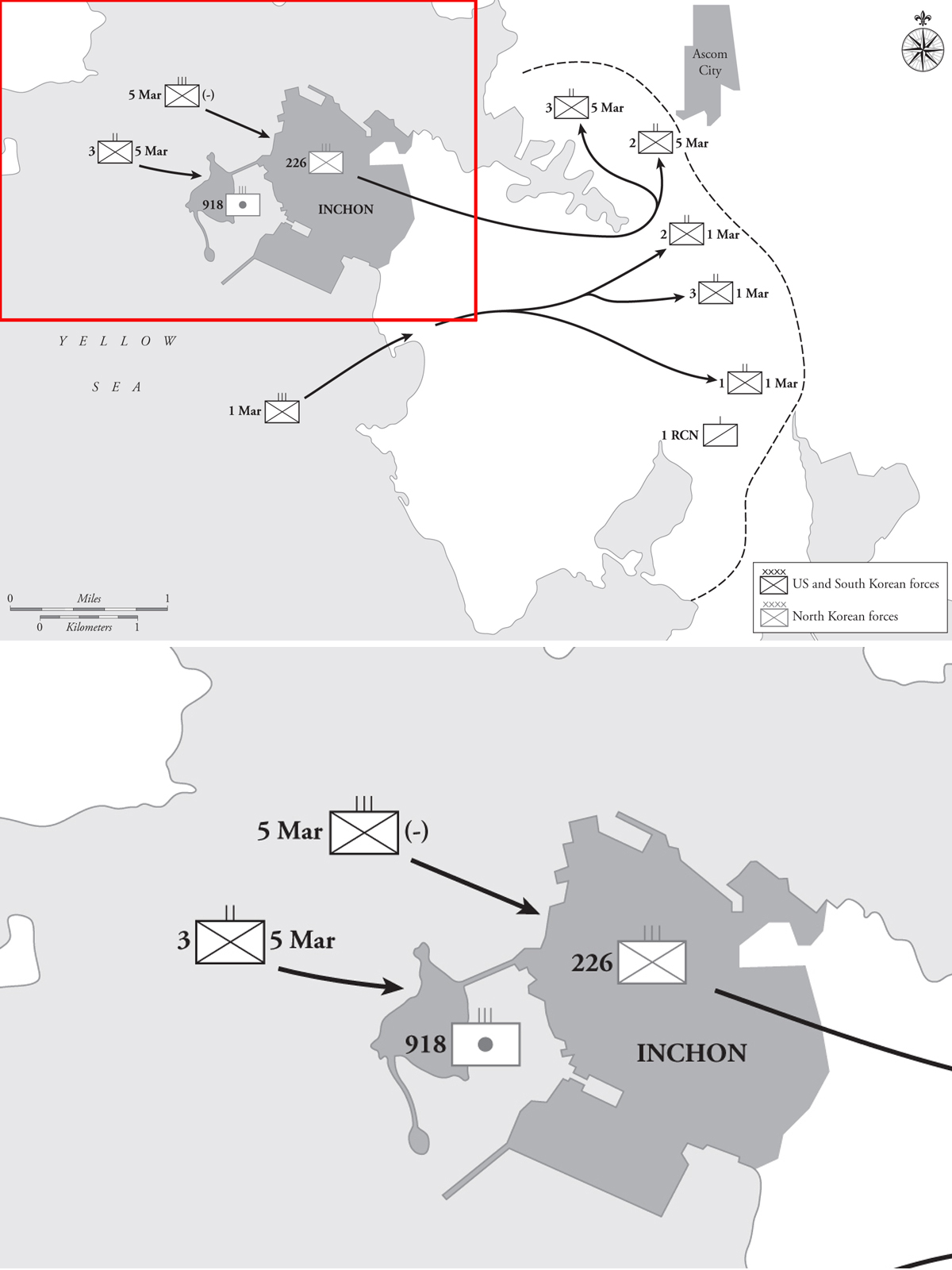

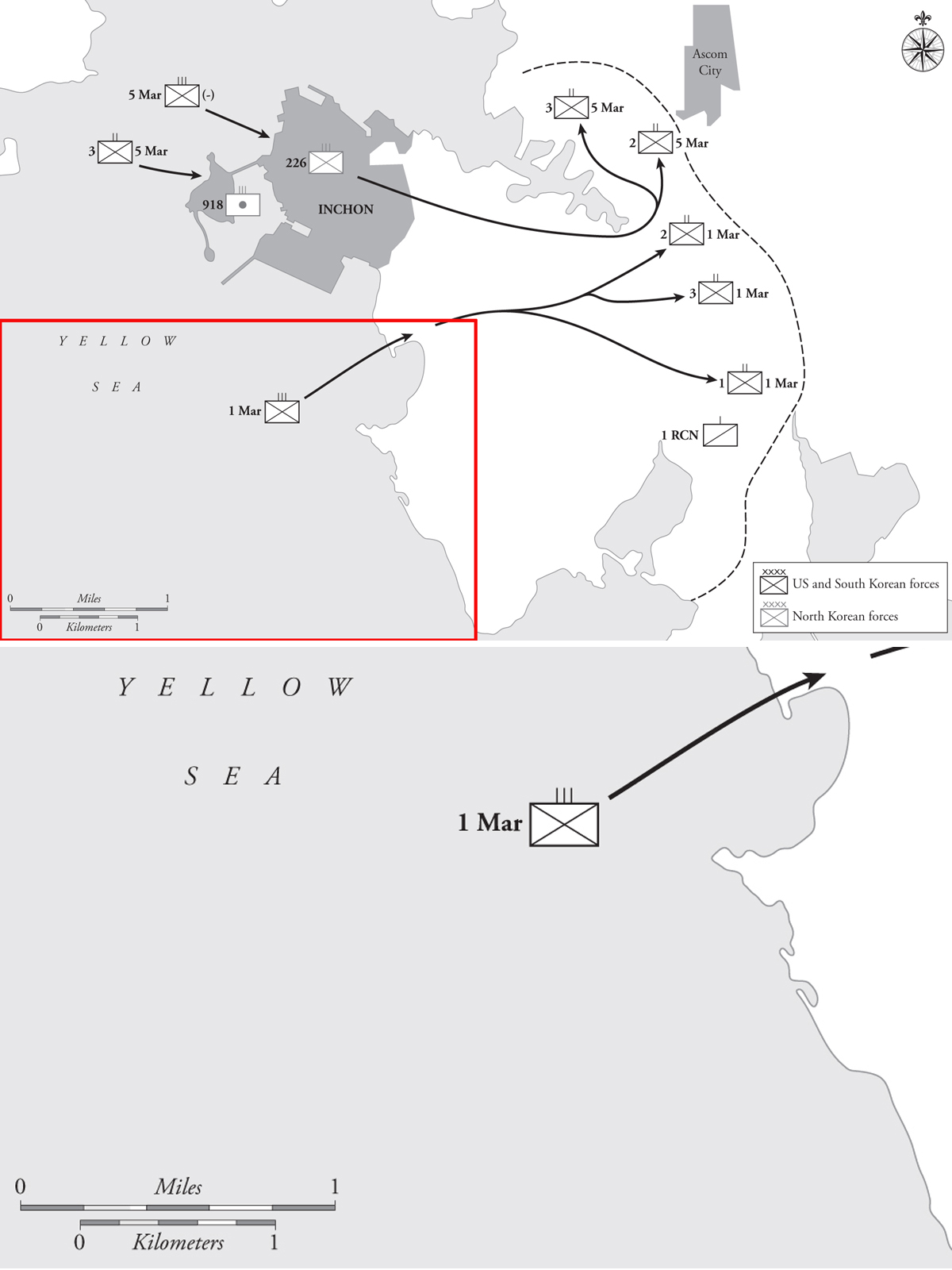

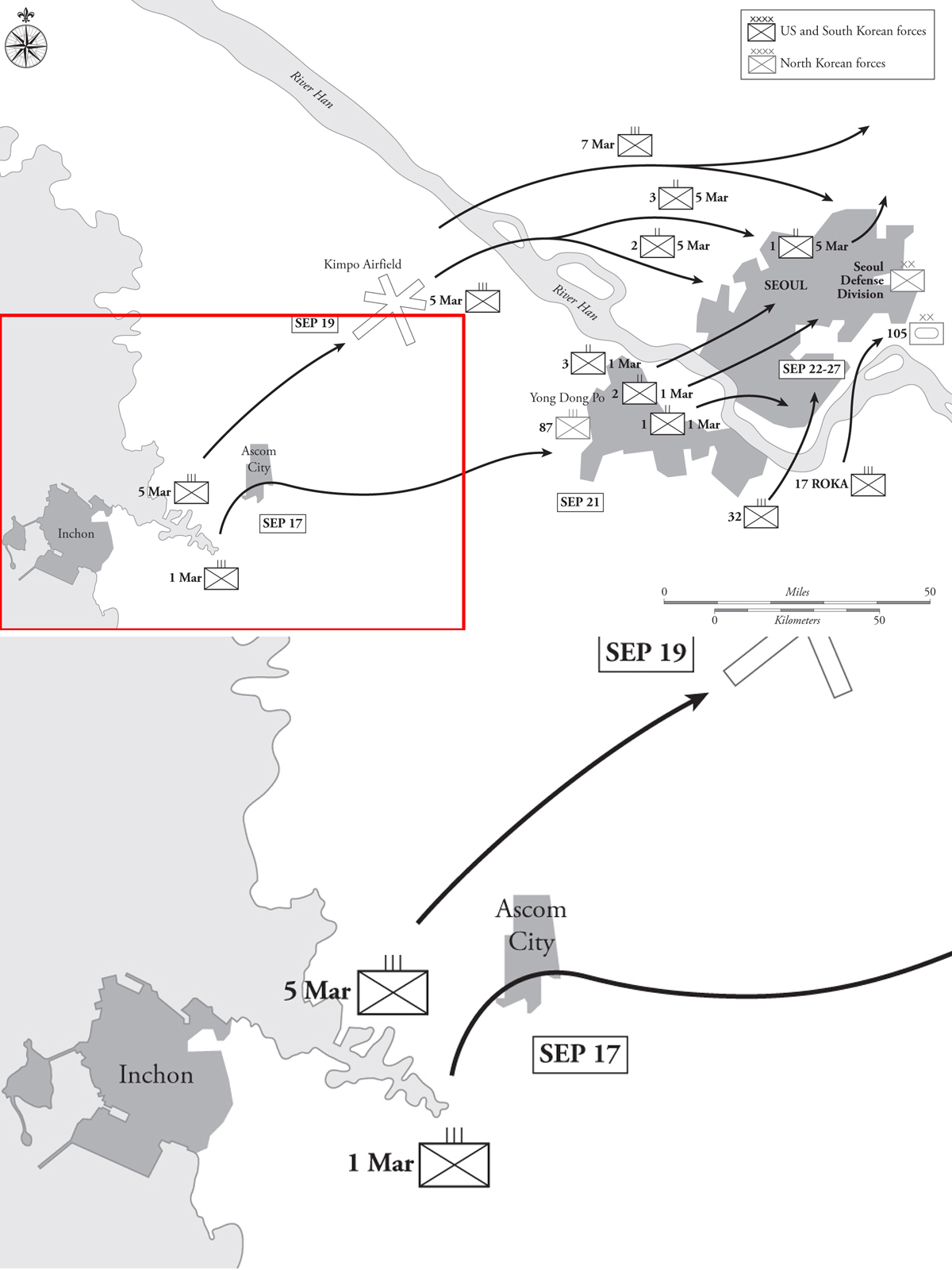

On September 15, the 1st Marine Division landed two regimental combat teams (RCTs), the 1st and the 5th Marine Regiments, south and north of the city of Inchon respectively. The landings, unusually, took place late in the afternoon, due to the tides. The two regiments secured their initial objectives quickly, overcoming relatively light resistance in Inchon itself. The North Korean defenders were surprised, shocked by the pre-invasion naval and air bombardment, and gave up all resistance during the night. The next day the 5th Marines marched through the abandoned city of Inchon to link up with the 1st Marines and begin the 18-mile movement to the capital of Seoul. The 1st Marines were directed to advance directly west with the objective of securing Yongdungpo, the major suburb of Seoul on the west bank of the Han River. The 5th Marines veered north to secure Kimpo Airfield, the major air terminal of the capital and the largest and most modern airfield on the peninsula, also on the west side of the river.

By September 17, the 5th Marines were in position to attack Kimpo Airfield. Fighting through scattered North Korean strongpoints, the RCT secured the southern edge of the airfield by the end of the day. To the south the 1st RCT fought its way through a series of North Korean roadblocks on the main Inchon–Seoul highway. By nightfall the 1st RCT had advanced about two miles.

During the night the North Koreans defending Kimpo staged several small-scale counterattacks against the Marines, all of which were beaten off successfully. In the morning of September 18 the Marines advanced across the airfield against light resistance and by 10am the airfield and surrounding villages were secure. On September 18 the first troops of X Corps’ 7th Infantry Division began to land at Inchon. Their mission was securing the major highway south of Seoul that was the lifeline of the North Korean army fighting desperately at Pusan.

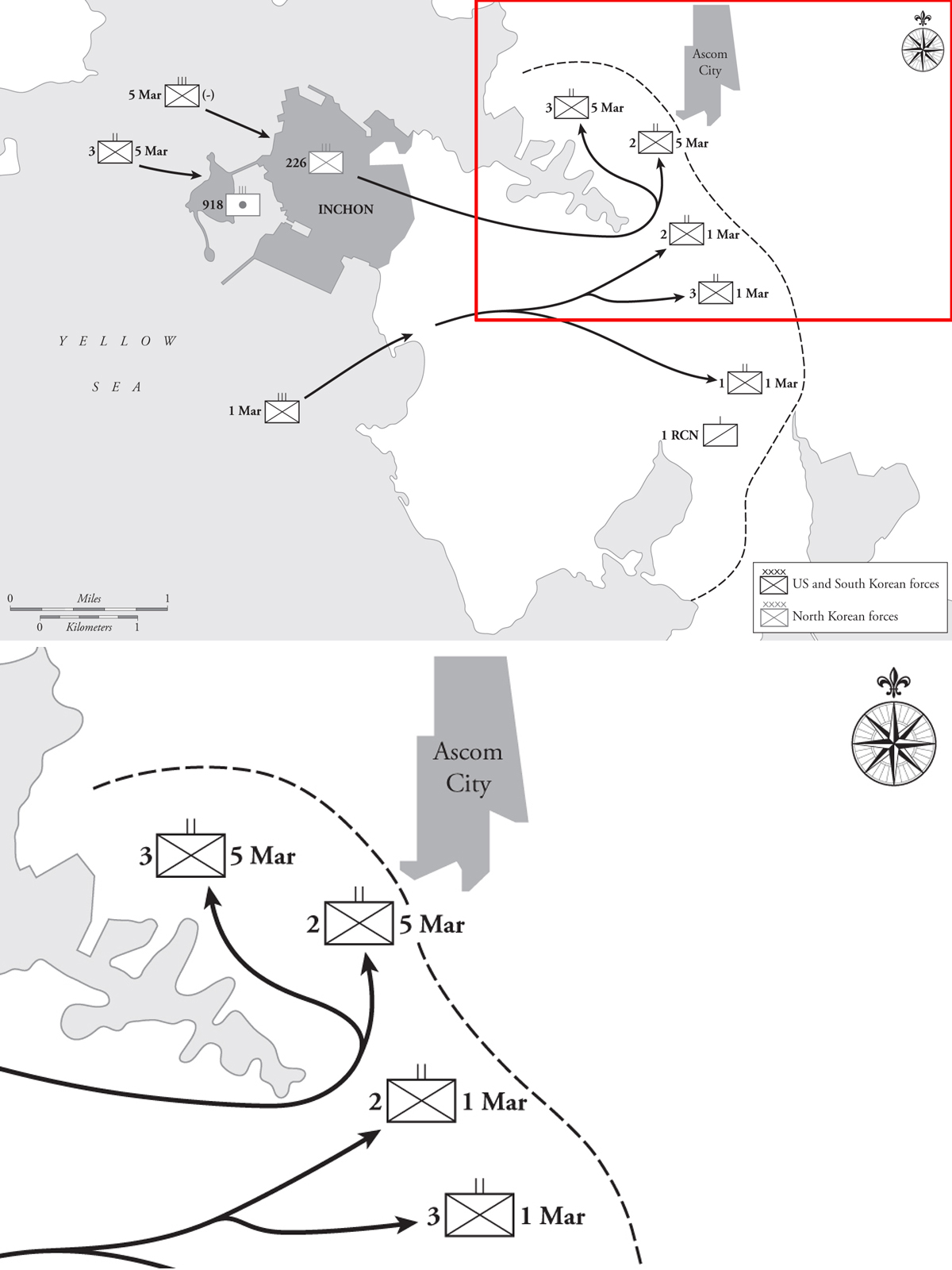

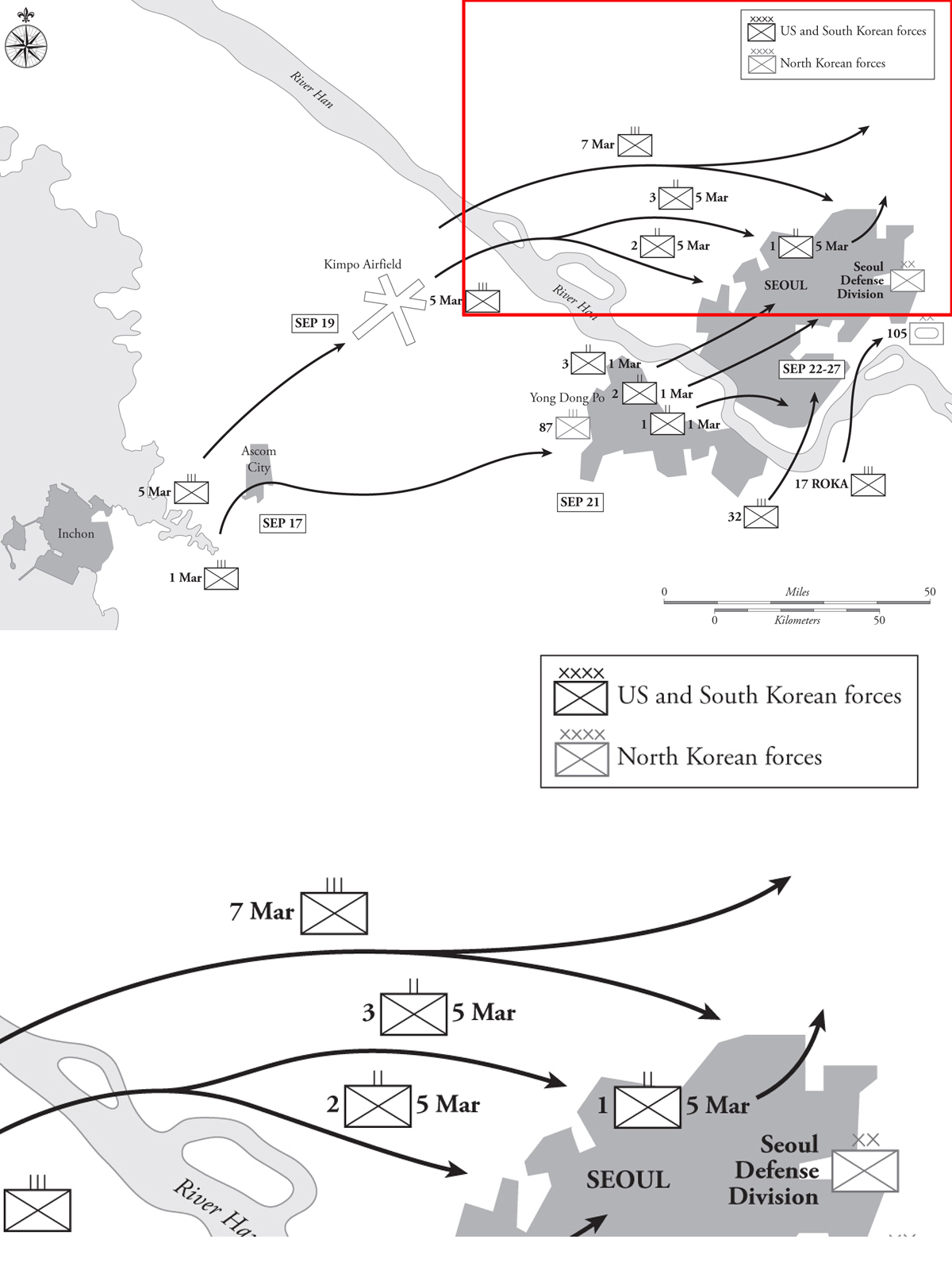

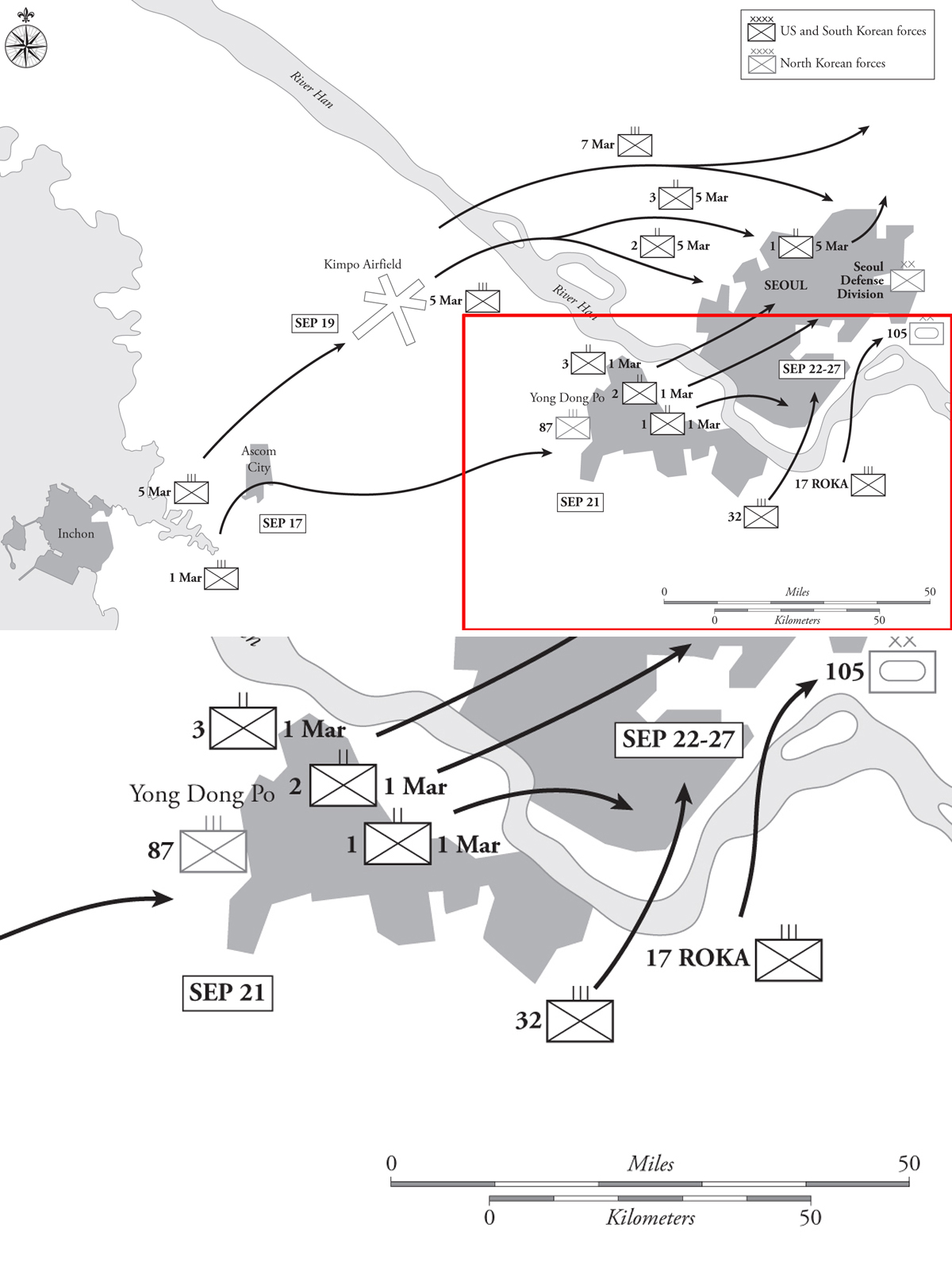

As the Marines closed in on the west bank of the Han River north of Seoul, the plan to recapture the city developed. The first phase of the plan involved securing a bridgehead on the east bank and bringing the entire west bank under control of the Americans. On September 20, the 5th Marine RCT crossed the Han north of Seoul and then wheeled right and began to attack the city from the north to the south. Simultaneously the 1st RCT entered Yongdungpo and began a building by building attack to clear the west bank of the Han. By September 23, the 1st RCT had accomplished its mission and was prepared to join the 5th Marines on the east bank.

The river assault of the 5th RCT was only lightly opposed. The Marines were mounted in LVTs (Landing Vehicles Tracked), literally amphibious armored personal carriers. These vehicles and crews were provided by the Marine 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalion, and the US Army’s 56th Amphibious Tractor Company. In addition, some Marines at Inchon and at the crossing of the Han River rode in army DUKW amphibious trucks of the 1st Amphibious Truck Company. Importantly, X Corps had no assault-bridging capability, so they could not put a military bridge over the Han. This meant that it was very time-consuming to move the important M-26 tanks of the 1st Marine Tank Battalion across the river to support the 5th RCT. Finally, as the plan was fashioned, four RCTs would participate in the battle of Seoul, each attacking in a set sequence. The sequencing of these attacks was all determined by the requirement that all four RCTs be moved across the river by the same single LVT battalion. Thus, the Han River obstacle shaped the assault on Seoul more than any other single factor.

The intent of the attack of the 5th RCT was to get behind the defenses of Seoul as the assumption was that the North Korean forces would be oriented south and southwest towards the approaches directly from Inchon. What the planners of the operation failed to account for was that the area northwest of Seoul was a former Japanese army training area, and had been improved by the South Korean army as a defensive line, so the positions were oriented north against attack from North Korea. Those prepared defensive positions were still in place and the North Korean army occupied them in defense against the attack of the 5th RCT. In addition, the North Korean army moved approximately 10,000 troops into these positions just prior to the Marines crossing the Han. Thus, though the 5th RCT covered 4 miles on the afternoon of river crossing, September 20, it then ran into stiff resistance. It would take the Marines five more days to fight their way across the last four miles of ridges between their landing site and Seoul.

On September 24, the 1st RCT crossed the river, assaulting directly from Yongdungpo into the heart of the city. With three battalions abreast, the 1st RCT attacked directly east through a series of roadblock barricades that the North Koreans had constructed on the major thoroughfares through the city. The 5th RCT wheeled left, and advanced on the left flank of the 1st RCT as both Marine units systematically cleared barricades, buildings, culverts, and sewers. Both regiments used their M-26 Pershing tanks extensively. Typically a single tank led a Marine infantry platoon as it systematically cleared the interiors of the buildings. The Marine tanks were virtually unstoppable, and easily brushed aside North Korean infantry, and also made short work of a few Soviet-built T-34/85 tanks found in the city.

On September 25, two additional regiments entered the battle for Seoul. One was the 32nd Infantry Regiment of the US Army’s 7th Infantry Division. The other was the 1st ROK Infantry Regiment, attached to the 7th Infantry Division. These two regiments, using the same LVTs as the 1st and 5th RCTs, crossed the Han River into the southern part of Seoul. Thus by September 25, the four allied regiments were on line advancing across Seoul. On the night of September 25–26, the North Korean army mounted a last major counterattack against the 5th, 1st, and 32nd Regiments. The attack against the 1st Marines was led by T-34 tanks and self-propelled assault guns. In the morning the two Marine regiments counted almost 500 enemy dead as well as nine destroyed armored vehicles and eight antitank guns in front of their positions. The steady advance of the three major regiments, supported by the 17th ROK Army Regiment, continued on September 26, and on September 27 the major portion of the city was cleared of communist forces and the X Corps lead elements were pursuing the enemy north through the mountains toward the 38th parallel. It had required 12 days for the X Corps to achieve its objective after landing at Inchon.

The only other major combat formation involved in the battle for Seoul was the 7th Marine Regiment of the 1st Marine Division. This regiment was still en route to Korea when the initial Inchon landings occurred. It landed at Inchon on September 21. The 7th Marines’ role in the Seoul operation was to isolate the city and prevent North Korean forces from escaping the city to the northeast. As the 5th Marines attacked into the city from the north the 7th Marines passed behind them and attacked east. Unfortunately, the direction of attack to the east was across numerous valleys divided by very rugged mountains aligned north to south, and the area was virtually unsupported by roads. Thus, though not strongly opposed, the attack proceeded very slowly. It was only on September 28 that the northeast escape routes were closed, and by then some of the best North Korean troops defending Seoul had escaped.

Map 4.2 The Capture of Seoul, September 1950

On September 29, 1950, General Douglas MacArthur and South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, arrived in the capital and General MacArthur declared the city secure. In fact, significant fighting continued as the American units in the city, aided by South Korean forces, continued to systematically clear buildings and streets. Nonetheless, the city was declared secured exactly 90 days after the outbreak of hostilities. The major portion of the 1st Marine Division moved to the eastern portion of the city and prepared to pursue the North Korean army north. Earlier, on September 26, at Suwon, 30 miles south of Seoul, elements of the US Eighth Army linked up with X Corps’ 7th Infantry Division. Between Seoul and Pusan, the North Korean army was completely shattered.

Large urban areas are very difficult objectives to seize except at great cost both in resources and time. The key to the successful capture of a large city, quickly and with minimum expenditure of resources, is to seize it before it is adequately defended. This is extremely difficult to do and can only be accomplished through one of three types of operations: airborne assault; amphibious attack; or a deep rapid armored thrust. General MacArthur recognized that a counteroffensive launched from the Pusan perimeter alone would likely devolve into a long and costly battle of attrition through the Korean mountains, and through numerous large urban areas, including Seoul. The Inchon landing operation, at some significant risk, avoided a war of attrition and resulted in the fall of Seoul in just over 10 days with minimum losses. Unlike most World War II urban battles, the battle for Inchon and Seoul was a battle of maneuver. This was primarily because the attacking force was able to achieve strategic surprise and thus the defender did not have the time to assemble forces and could not establish a comprehensive defense of the entire city area.

The US Marine approach to urban warfare in Seoul was relatively straightforward. Seoul was a huge city which, with Yongdungpo, covered about 80km2 (30 square miles). Despite having more than 20,000 troops available, the North Korean Army had insufficient manpower to defend a continuous line of buildings. The North Korean forces in the city choose to defend fortified barricades oriented on the major avenues and significant natural and city terrain features. The fight for the city became known as the battle of the barricades. Along the city streets the North Korean army erected barricades, constructed of whatever material the North Koreans could find within the city. This included rubble and dirt-packed rice bags, bricks, household furniture, old cars and buses, and any other obstacle-making device they could find. These were torn down by the US and ROK infantry and engineers, or driven over by US tanks. The Marines developed a standard approach to the barricades: artillery fire on the area followed by mortar fire on the position; machine-gun and bazooka fire to suppress the enemy while engineers cleared mines; and finally with the mines removed, the tanks moved forward. The powerful US M-26 tanks were often able to simply plow through the assorted debris. With the tanks came the Marine infantry armed with semiautomatic rifles, fixed bayonets, and grenades. Marine scout-sniper teams overwatched all operations and took a deadly toll on any enemy not behind cover. Each barricade was stoutly defended by North Korean infantry supported by antitank guns, machine guns, and snipers; and took about 45 to 60 minutes to reduce. Thus the movement through the metropolis was of necessity slow, but steady.

A potentially major threat to the US operation was the Soviet-built T-34/85 tanks of the North Korean People’s Army 105th Tank Division. In the march from Inchon to Seoul, 53 of these lethal machines were thrown into counterattacks against the Marines. These tanks had been extremely effective combat vehicles against the best German armor in World War II just five years before. They also furthered their reputation in the first weeks of the North Korean invasion. However, after the initial encounter, the Marines were completely nonplussed by their arrival on the battlefield. They were easily destroyed by a combination of Marine close air support, Marine M-26 tanks, and antitank weapons. By the time the Marines secured the west bank of the Han River, 48 had been knocked out by the Marines and five were found abandoned. In the battle for Seoul itself, the 1st Tank Battalion destroyed 13 T-34 tanks or Soviet-built self-propelled guns and 56 antitank guns, for the loss of five Pershing tanks and two Shermans (most of the American tank losses were to mines and at least one was lost to one of the frequent attacks by North Korean sappers armed with satchels of explosives). Importantly, North Korean armor was of sufficient strength that it could have completely disrupted the US operation, had the US not enjoyed close air and armor support. Thus, armor and close air support were again proven to be very important factors to successful urban combat.

The relatively small size of the US attacking force was possible due to effective air, naval, armor, and artillery support. The air support of the Marines in the Inchon-Seoul operation was particularly effective and noteworthy. Marine aviation units perfected the art of close air support during the Korean War, beginning in the Inchon–Seoul battles. That support was far more responsive and closely coordinated than that achieved by the Marines in World War II. Six Marine squadrons (four day-fighter and two night-fighters) supported the 1st Marine Division and X Corps during the operation. They were controlled by the 1st Division’s 1st Marine Air Wing. They had no other mission other than close air support of the ground forces. Initially the Marines flew in support from two navy escort carriers, the USS Badoeng Strait and the USS Sicily, but once Kimpo airfield was captured, the five F4U Corsair squadrons and the one F7F Tigercat squadron operated from that base, literally minutes from their targets. Close air support was coordinated by Marine Tactical Air Control Squadron 2, which commanded tactical air control parties (TACP) located in each Marine infantry regiment and battalion headquarters. When the US Army 32nd Infantry Regiment entered the battle for Seoul, a Marine TACP was attached to the regiment to give it the benefit of close air support. During the 33-day campaign, September 7–October 9, the Marine aviation units flew almost 3,000 ground-support sorties, including over a thousand in support of the Army’s 7th Division.

Aviation support was critical to the advance from Inchon to Seoul. It was particularly critical to the 5th RCT’s difficult attack south on the east side of the Han River. However, once units entered the city proper the use of close air support became increasingly difficult because of the difficulty of identifying the front line from the air and the danger to the friendly civilian population. Still, even as the battle raged inside Seoul, close air support played an important role aiding the advance of the 7th Marine Regiment through the mountains north of Seoul, isolating the city from reinforcements, and destroying KPA units attempting to retreat from the city.

One of the major characteristics of the fight for Seoul was the intense pressure put on the Marine division to capture the city quickly. This pressure was resented by the Marine officers because speed often caused them to take risks with the lives of their Marines. Often this was viewed as General MacArthur placing politics before the tactical considerations of urban combat. However, there were good reasons to take the city quickly. First, the military advantages of cutting off the bulk of the KPA south of Seoul were obvious. Second, and perhaps most important, were the psychological and political advantages to be gained by recapturing the city less than three months after its capture by the KPA in June. The capital of Seoul defined the allied government of the Republic of Korea and restoring that city to allied control was extremely important strategically to the prestige and legitimacy of the South Korean government. MacArthur understood how strategic Seoul was to the South Korean government, as well as to the UN cause and to the US home front, which desperately needed positive war news. Thus, like many important capital cities in warfare, the strategic value of the city was worth the tactical sacrifices necessary to capture it, and capture it quickly.

Siege towers were important for the conquering of cities for hundreds of years. They were mobile, provided cover, could be used as a base for fring weapons, and most importantly, allowed the attacker to breach the protective city walls. Soon after the arrival of gunpowder, vertical protective walls and the siege towers used to attack them, became obsolete. (istockphoto)

Capturing cities was a major focus of ancient and medieval warfare. The challenge was breaching the city walls – once that occurred the battle was over. However, often the attacker chose to wait and let starvation take its toll on the garrison and population. In those situations the cost in lives of noncombatants would be tremendous. (David Nicolle)

The fortress city of Neuf-Brisach which is a near-perfect example of the early modern “star” fortress. Unlike many such cities, Neuf-Brisach was designed by Vauban in 1698 as a combination fortress and city, with both elements built simultaneously. The fortress city was intended to guard the French border in Alsace. (Getty)

The primary weapon in urban combat: the infantryman. A German infantry corporal in the late summer or early fall of 1942 at the gates of Stalingrad. He is clutching an entrenching tool and wears a black wound badge indicating he has been wounded once or twice. He also wears the infantry assault badge on his pocket indicating participation in three or more infantry combat operations. (Bundesarchiv)

A JU-87 “Stuka” dive-bomber over Stalingrad in the late summer or early fall of 1942. The Germans provided excellent close air support for the Sixth Army during the fall campaign to capture the city. Each German attack was preceded by a Luftwaffe bombardment. This picture also illustrates the width of the Volga river which would have required a major operation on the part of the Germans to cross. The Soviets were able to ferry men and supplies across the Volga and into the city throughout the entire campaign. (Bundesarchiv)

German infantry captain observing the Stalingrad battlefield in October 1942 from a position near the ruins of the Barrikady weapons factory. He is armed with a captured Soviet PPSh sub-machine gun. Sub-machine guns were ideal for urban fighting where engagement ranges were short, numerous targets appeared in a small area, and space for aiming and firing a weapon could be tight. (Bundesarchiv)

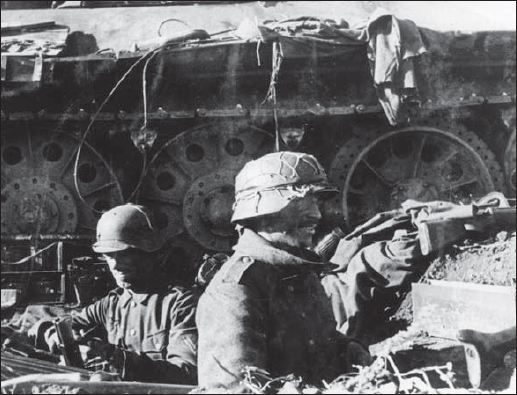

German infantrymen dug into a fighting position. The infantryman in the foreground is armed with the standard German infantry rifle of World War II, the 7.62mm Kar98k. The German position is built next to a knocked-out Soviet T-34 tank. (Bundesarchiv)

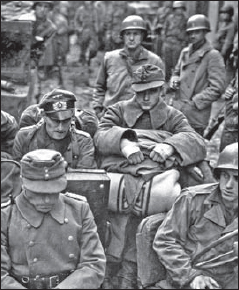

German infantry preparing for one of the last assaults to clear the Soviet Army from the west bank of the Volga in late fall 1942. For the infantry, Stalingrad was an unrelenting battle with no respite. The exhaustion caused by intense urban combat is evident on the faces of these men as they ready themselves to attack once again. (Bundesarchiv)

A Sturmgeschütz IIIa (StuG IIIa) maneuvers through the dust of Stalingrad in September 1942. The Sturmgeschütz III was a tracked infantry support vehicle, not a tank, and specifically designed to assist infantry reduce fortifications. It did not have a turret but had very thick frontal armor and was ideal for urban warfare. (Bundesarchiv)

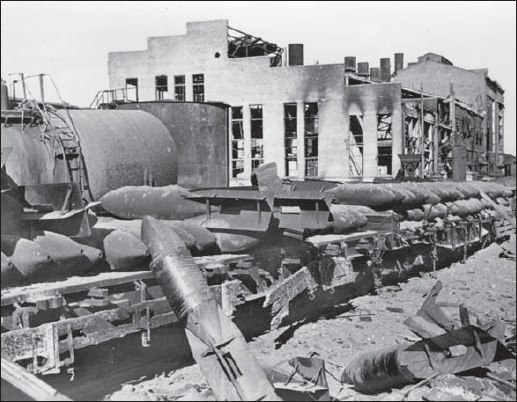

Russian aerial bombs loaded on a rail car outside Stalingrad’s tank factory in November 1942. The tank factory was one of several large industrial complexes big enough that armored vehicles could fight inside the building. (Bundesarchiv)

A StuG IIIa carrying infantry to battle in Stalingrad, October 1942. The StuG IIIs were not part of the panzer corps but rather part of the German artillery corps because of their unique role of directly supporting the infantry. As evidenced in this scene, two months into the battle the city infrastructure was essentially destroyed. (Bundesarchiv)

Panzerkampfwagen IIIj (PzKpfw IIIj) of the 24th Panzer Division during the march to Stalingrad in the summer of 1942. The track draped across the front is intended to add some additional armor protection. The PzKpfw III was notoriously outgunned and less armored than its Soviet counterparts, but it still was a formidable opponent due to superior command and crew abilities. Most of the Sixth Army’s tanks were committed to the city fighting in Stalingrad when the Soviets launched their powerful counterattack in November and the 24th Panzer Division was caught in the surrounded city. (Bundesarchiv)

Sherman tanks move carefully through a town near Aachen. In addition to its firepower, the tank, when working in close coordination with infantry, could provide mobile cover from small-arms fire and allow infantry to close on a building. (NARA)

Field Marshal Walter Model, commander of Army Group B which included the Aachen area. Known as “Hitler’s fireman” for his ability to save desperate situations, he gave Aachen high priority and committed some of the best German units available to its defense. (Bundesarchiv)

Colonel Gerhardt Wilck (front left), commander of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division and the Aachen garrison. He had very specific orders from Hitler to defend the city to the last man and if necessary allow himself to be buried under its ruins. (NARA)

The Americans reorganized their infantry companies as assault units by attaching special equipment, engineers, and tanks to the companies. These were then divided amongst the platoons, making each platoon an individual assault team. Machine guns covered the streets while infantry moved through the building interiors as much as possible. (US Army)

Sherman tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion support the 30th Division as it attacks to isolate Aachen. Though the Sherman tank was not the best tank of the war, in urban operations any armored vehicle is a critical asset to the attacking force. (NARA)

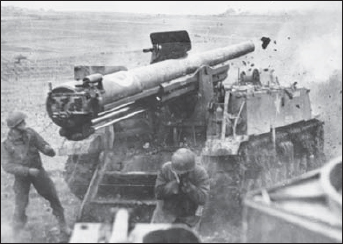

An M12 155mm Gun Motor Carriage (self-propelled gun) in action in Aachen. Tank guns and ammunition were not always sufficiently powerful to have great effects on the concrete and stone buildings of Aachen. Although primarily designed as an indirect-fire artillery weapon, M12s were specifically requested by the 1st Infantry Division for direct-fire support against buildings and bunkers. The powerful gun could bring down an entire building with one shot. (NARA)

A 57mm antitank gun fires on German defenses. The 57mm guns were somewhat effective at suppressing German defenders in buildings, allowing infantry to close in and assault the position. (NARA)

A 3in. antitank gun of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion establishes a position outside Aachen to guard against German armor. The Germans committed a significant amount of armor, including King Tiger tanks, in counterattacks to attempt to keep access to Aachen open. (NARA)

An M-4 tank of the 745th Tank Battalion in Aachen. Tanks operating in Aachen had to be very careful not to remain exposed on the open street for too long and not to get separated from the infantry they were working with. The German Panzerfaust anti-armor weapon was widely distributed among German infantry, easy to use, and deadly to the Sherman tank. (NARA)

German prisoners marching into captivity. Over 3,000 prisoners were captured in the main part of Aachen, which was attacked by two battalions of the 26th Infantry Regiment. (NARA)

US Marine Corps F4U-5 Corsair of VMF-312. The 1st Marine Division’s air wing gave them and the entire X Corps great flexibility in supporting the attack into Seoul. When the corsairs moved to Kimpo airfield it was possible for pilots to drive by jeep and visit the forward regiments and then return to the airfield to fly missions the same day. (USMC)

Marines of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines scale the seawall on the northern side of Red Beach, as the second assault wave lands at Inchon, September 15, 1950. Wooden scaling ladders are in use to facilitate disembarkation from the landing craft. (USMC)

A Marine squad on the approach to Seoul. Dispersal was essential because, though the main North Korean defensive position could be easily spotted, hidden snipers were a constant threat. (USMC)

A Marine squad, supported by an M-26 General Pershing tank of the 1st Marine Tank Battalion, moves through Seoul under fire. (USMC)

A Marine squad in Seoul suppresses sniper fire with small arms. The Marines are armed with M1 carbines and the M1 Garrand semi-automatic rifle. Outside the building in the background, is a Marine M-26 tank. (US Army)

Marines evacuate a wounded comrade down a street in Seoul. (USMC)

A Marine raises the American flag above the US consulate in Seoul, September 27, 1950. (Getty)

A US M-4 Sherman tank pushes another Sherman tank onto a Landing Ship Tank (LST) at Inchon for evacuation to Japan and repair. In the Marine 1st Tank Battalion, Sherman tanks were used as flamethrower tanks and as dozer tanks because those capabilities had not yet been adapted to the M-26. (US Navy)

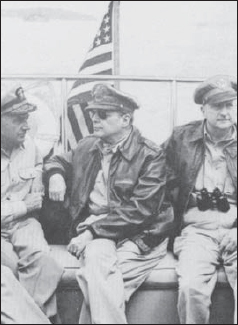

US Army General Douglas MacArthur (center) conceived and supervised the Inchon-Seoul campaign. Many analysts believe it was his finest operation. He clearly understood the important political symbolism of recapturing Seoul. (US Navy)

A USMC M-48 tank supporting the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, in the battle for the citadel in Northern Hue. (USMC)

USMC M-48 tank overlooking the Highway One bridge over the Phu Cam Canal. The PAVN destroyed the bridge late in the battle, too late to stop USMC reinforcements moving into the southern part of the city. (USMC)

Marine riflemen, armed with M-16 assault rifles, establish a second-floor position overwatching a walled garden in Hue. (USMC)

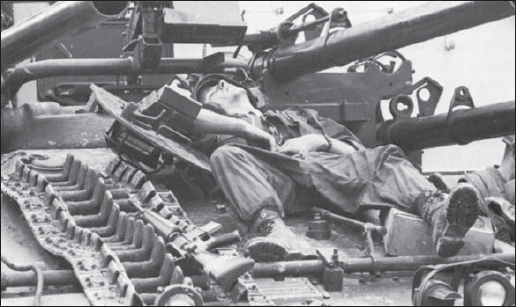

A Marine Ontos crewman lays exhausted across the front of his vehicle. The 106mm recoilless rifle, six of which were mounted on the Ontos’ lightly armored frame, was the perfect weapon for punching holes in the sides of Hue’s concrete buildings. The dust cloud raised by firing the weapon also provided concealment as the Marines rushed across streets to assault buildings. (NARA)

Another characteristic of the battle for Inchon–Seoul was the integration of South Korean forces into the battle. There is no doubt that South Korean forces were not necessary to the battle. However, General MacArthur insisted that the ROK Marine Regiment and the 17th ROKA Infantry Regiment be integrated into operations and participate in the recapture of Seoul. Again, this insistence demonstrated that the fight for a capital city such as Seoul was as much about perceptions and information operations, as it was about tactics. The role of ROK infantry and Marines in the battle was small, but the prestige incurred by the ROK government was huge, and the battle did much to boost the morale and confidence of the ROK military which eventually would assume the largest burden of combat operations in the war and would prove itself capable of fighting not just the KPA, but also the Chinese Army effectively.

A final characteristic of the campaign for Seoul and the battles for Inchon and Seoul was the nature of the assaulting force. The assault force, X Corps, was a unique organization. Though its composition was strongly influenced by the lack of available forces in the early days of the Korean conflict, it was also uniquely tailored to the needs of modern urban combat. The X Corps was a true joint-service force, and a combined allied force, and thus had capabilities not found in a typical army corps. As a joint force it had unique amphibious, naval support, and close air support capabilities which were all critically necessary to the strategic situation, and the tactical problems involved in the recapture of the Korean cities. The leveraging of the capabilities of air and naval power reduced the need for large numbers of infantry, and reduced the casualties among the attacking US and ROK Marines and infantry. The navy ensured strategic surprise and supported the force logistically, and with naval gunfire. The air component augmented artillery fires, protected the force from North Korean airpower, and helped isolate the urban battlefield. Both air and naval forces provided a psychological boost to the assaulting US and ROK Marines and infantry, and demoralized the KPA defenders. As a combined US and ROK force, X Corps represented the unique political nature of the Korean conflict, and maximized the strategic gains that the recapture of the ROK’s capital represented. Neither a single-service corps, nor a completely American corps, could have conducted the operation as effectively, or achieved the same strategic success that the uniquely joint and combined allied X Corps was able to achieve. In many ways X Corps represented an ideal urban fighting organization.