Almost 20 years would pass before American military forces found themselves involved in a situation where urban combat skills were again important. Ironically, the next major city fight involving US forces came during the Vietnam War, a war known for its sharp conflicts in the mountains, jungles, and rice paddies. Vietnam was not a war generally associated with urban fighting, but in the winter of 1968, when the North Vietnamese launched the famous Tet Offensive, one of the major objectives of the offensive was to bring the war into the major urban centers of South Vietnam. One of the most decisive, hard fought, and dramatic of the 1968 battles was the battle for the city of Hue which began in the early morning of January 31.

Hue was one of the oldest and most revered cities of Vietnam, North and South. It was the ancient imperial capital of Vietnam, and also the center of the Catholic church of Vietnam. It remained, under the government of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), the capital of Thua Thien Province. It was South Vietnam’s second largest city, covering an area of 67km2 (26 square miles), and home to a population of approximately 280,000 people. Hue was a coastal city, positioned where the Perfume River empties into the East China Sea. The river bisected Hue from east to west, dividing it into a northern and southern half. The northern portion of the city was older, and was dominated by the 18th-century Imperial Palace and citadel. The southern portion of the city was more modern and consisted of the main government buildings as well as Hue University. The Perfume River was crossed north to south by two important bridges. One was a railway bridge located in the western portion of the city and the other was a highway bridge supporting Highway One, the primary north–south roadway. Though not a major port, Hue also included a US Navy facility that permitted the offloading of supplies. Because of the bridges, highway, and port, Hue was an important transportation center along the logistics line that connected the major military logistics bases further south and the important military positions such as Kha Shan, north of Hue along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Vietnam. Though there was no doubt that Hue was an important urban area to the South Vietnamese government because of its size, history, military significance, and governmental role, an agreement between the two opposing governments, the southern Republic of Vietnam and the northern Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), declared Hue an open city that would not be used for military purposes by either side. For this reason, despite some warning that a major North Vietnamese offensive might be looming, the South Vietnamese and American militaries were not overly concerned with defending Hue itself.

Prior to the launching of the Tet Offensive, the American command in South Vietnam, under US Army General William Westmoreland, was satisfied with the progress of the war. The year 1967, the second full year of the major American military commitment to Vietnam, had been a year full of battles. American casualties were high, but intelligence estimates were that the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong had suffered significantly worse. As the year ended the US commander traveled back to the United States to give President Johnson a personal, upbeat assessment. It was thus in December 1967 that General Westmoreland declared that he “could see the light at the end of the tunnel,” implying that the end of the war was not far off. Because of this assessment, the Tet Offensive came as a complete strategic surprise to the US and South Vietnam, despite some military indicators of an impending attack.

North Vietnam also recognized that South Vietnamese and American military operations were generally achieving success in their efforts to expel the North Vietnamese military from South Vietnam, and subdue the Viet Cong. Because of this, the DRV determined that the situation in the South would continue to deteriorate unless they made a bold move. General Vo Nguyen Giap, commander of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), received permission from the DRV government to launch a general offensive in the South in 1968, supported by a general uprising of South Vietnamese communists. The PAVN scheduled the offensive to begin during the Tet holiday, a time when much of the South Vietnamese army would be on home leave. The objective was to use a combination of PAVN regular troops, in conjunction with the Viet Cong, to strike at key targets, mostly urban areas, throughout the South. American and South Vietnamese army forces would be destroyed as they counterattacked. Simultaneously, a spontaneous general uprising of the South Vietnamese population against the RVN’s government would ensure the destruction of the South Vietnamese government.

The city of Hue was assigned as the objective of the Tri Thien Hue Front command. The North Vietnamese plan to take the city was relatively simple. Viet Cong guerrillas, in civilian garb, would infiltrate the city in the days before the attack. They would observe targets and position themselves for the attack. On the night of the attack, the Viet Cong would spearhead the attack on the civilian targets and join with two battalions of PAVN sappers to attack military and government positions in the city. Two full regiments of PAVN infantry would then flow into the city to prepare it for defense against the inevitable counterattack. A third PAVN infantry regiment had the task of ensuring that the PAVN line of communications into Hue remained secure.

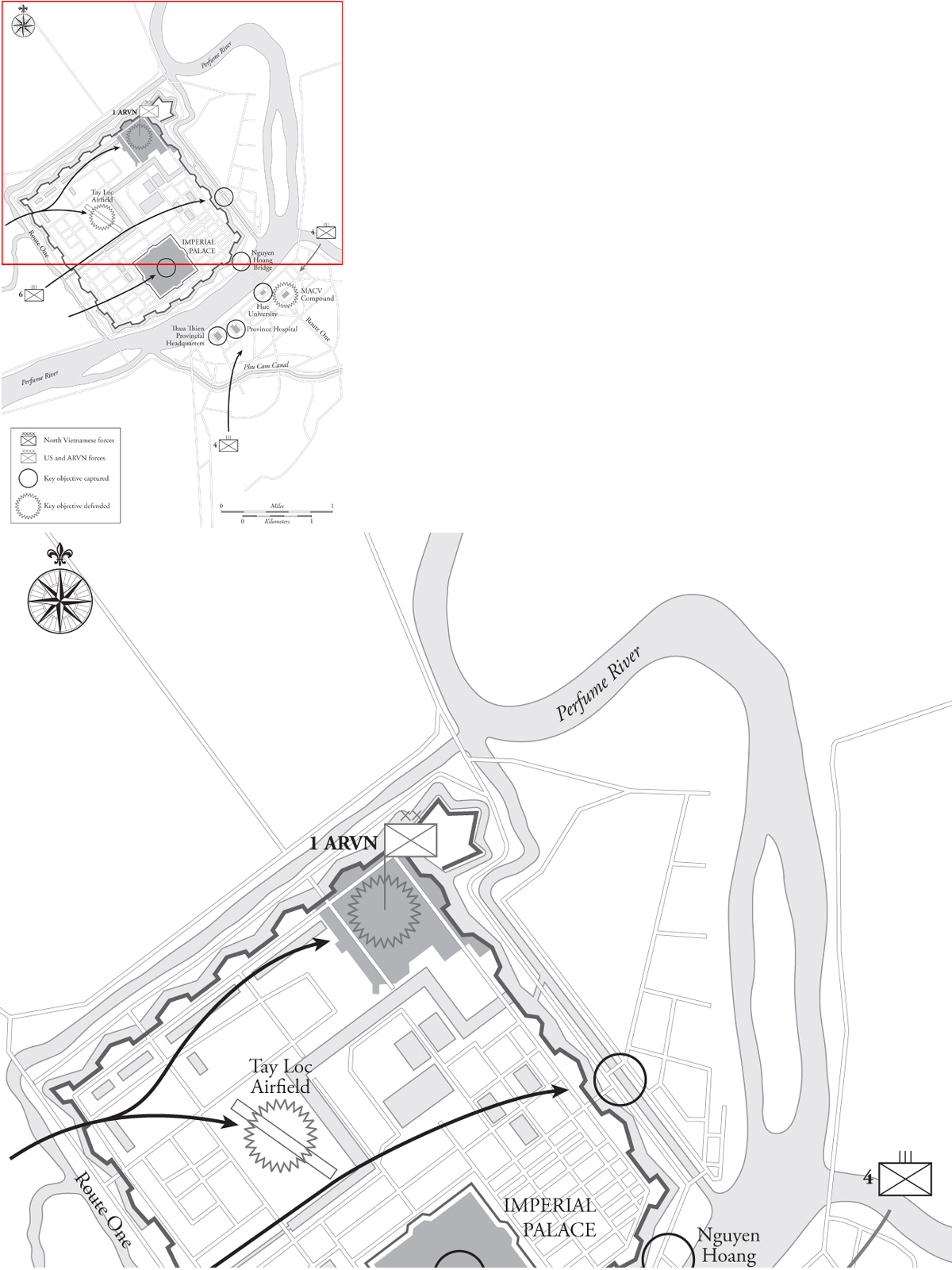

The Viet Cong and PAVN launched their attack in the early, dark hours of January 31, 1968. It was timed to coincide with hundreds of other attacks all over South Vietnam, and achieved complete surprise. The initial attacking force, numbering perhaps as many as 10,000 PAVN and Viet Cong troops, captured most of the city with virtually no resistance. The PAVN 6th Regiment entered and secured the Citadel area north of the river aided by Viet Cong in South Vietnamese army uniforms who overwhelmed the Citadel’s west gate guard detail. The PAVN 4th Regiment quickly secured the south side of the river. The PAVN troops had received special training in urban fighting and immediately began to dig in and prepare defenses. Outside of the city, the PAVN 5th Regiment set up defensive positions to protect the attackers’ line of communications and supply into the city. At the same time that regular troops prepared for the inevitable counterattack, a special cadre of political officers moved through the city with a list of several thousand individuals to be placed under arrest.

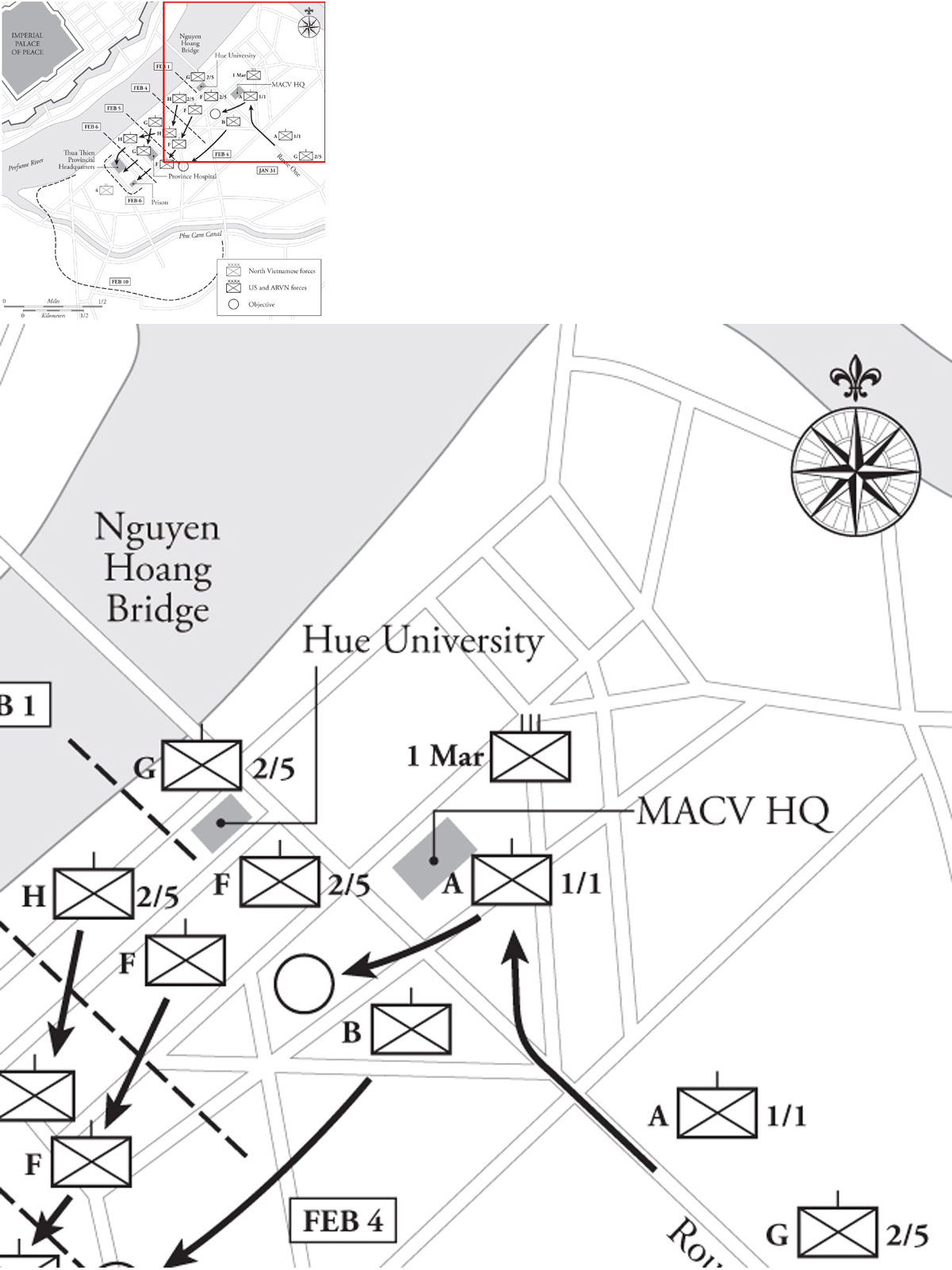

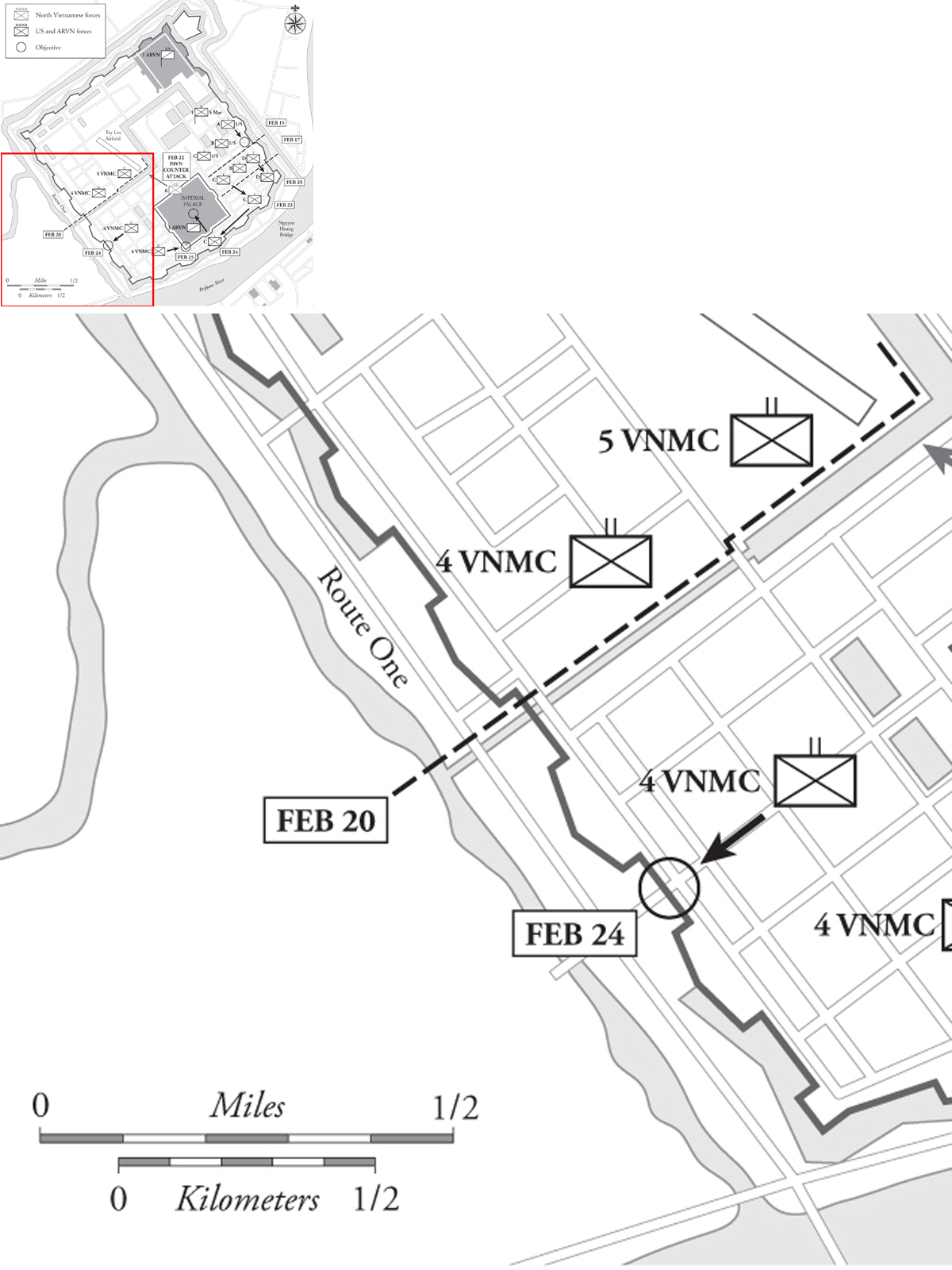

Map 5.1 The PAVN Capture of Hue, January 1968

Though the attack to capture Hue was a remarkable feat of arms that used stealth, intelligence, and boldness to seize the city with almost no fight, the execution of the assault was not flawless. The North Vietnamese had identified literally hundreds of large and small objectives inside the city, but the three most important were the headquarters of the 1st Army of Vietnam (ARVN) Infantry Division in the northeast corner of the Citadel; Tay Loc airfield, also in the citadel just to the north of the Imperial Palace; and the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) compound, which housed the 1st ARVN Division’s American advisors, located on the south side of the river. The commander of the South Vietnamese division, Brigadier General Ngo Quang Truong, had had several indicators of an impending attack and therefore had his division on full alert. His headquarters was fully manned and operating, as were all of his units, although over half of the division’s strength had been released on leave for the Tet holiday. General Truong was mistaken in his assumption that the North Vietnamese attack would not be directed at Hue itself, because of the city’s unique status and importance. Nonetheless, when the PAVN attack came, Truong’s division was alert and ready to respond.

The PAVN 6th Regiment’s attack through the Citadel moved rapidly from the southwest to the northeast. Little resistance was met until the North Vietnamese attacked Tay Loc airfield. The airfield was defended by the 1st ARVN Division’s reconnaissance company, an all-volunteer elite unit that, though outnumbered, held the airfield against repeated PAVN attacks. The 6th Regiment’s assault did not slow at the airfield but rather flowed around it and ran into Truong’s alert 1st ARVN headquarters. Like at the airfield, Truong’s headquarters troops resisted fiercely inside their walled compound. The PAVN attack had been preceded by a rocket bombardment of the entire city. That bombardment alerted the personnel of the MACV compound on the south side of the city. Thus, when sappers and troops of the PAVN 4th Regiment assaulted the MACV position they were met by a hail of fire from the first of the compound’s defenders to get to their positions. A machine gun on top of a 20ft tower, manned by a US Army advisor, mowed down the first wave of attackers. Similarly, a key bunker occupied by several US Marine advisors was manned and firing to stave off the first assaults on the compound gate. Though both positions were rapidly silenced by the PAVN, they delayed the attack just long enough that the remaining garrison was able to man defensive positions, beat back the attack and inflict severe casualties. Thus, though the PAVN attack was very successful in capturing 95 percent of the city, it failed to capture the three most important military objectives in the city. Although the airfield and two compounds were small failures compared to the wide success of the PAVN almost everywhere else, they were to prove decisive as these positions became the basis of the counterattack to retake the city.

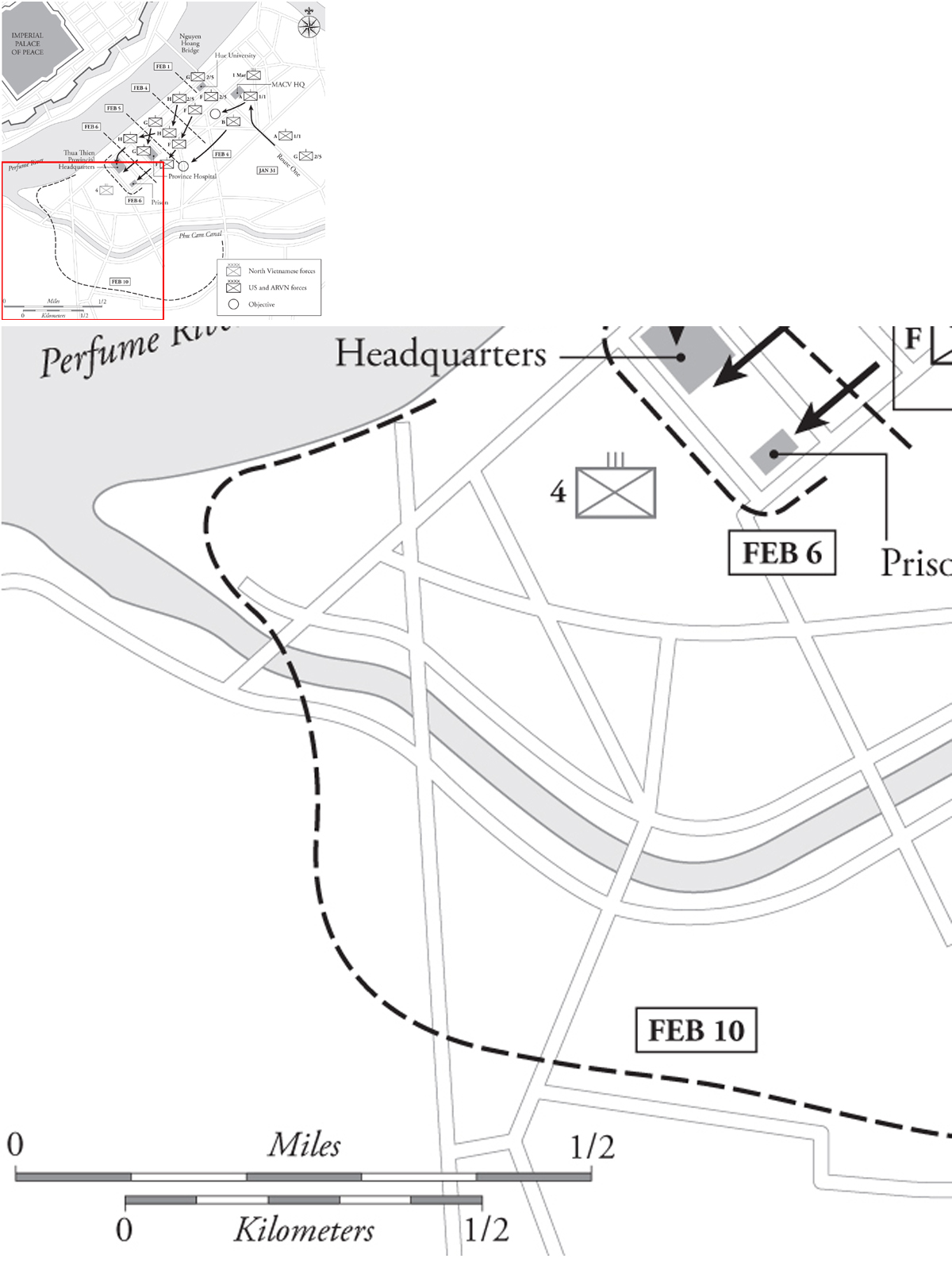

By the morning of January 31, the PAVN was firmly in control of Hue, and PAVN soldiers openly patrolled the streets of South Vietnam’s second largest city. Fighting raged at the airfield, while the PAVN were content to bombard the 1st ARVN headquarters and MACV compound with rockets. The ARVN and MACV radioed for reinforcements but all over South Vietnam chaos dominated on the first full day of the Tet Offensive. The requests for assistance were lost in the avalanche of reports that deluged all major headquarters across the country. Slowly, however, a response was formed and the outline of the battle for Hue emerged. The remaining battle would occur in three distinct phases which were related, but generally independent of each other. One battle occurred on the north side of the river between the ARVN and the PAVN 6th Regiment. A second battle occurred on the south side of the river between the PAVN 4th Regiment and US Marines. A third and final battle integral to the operation to recapture the city occurred to the west and north of the city between the PAVN 5th Regiment and elements of the US 1st Cavalry Division.

Marine Lieutenant General Robert Cushman III was responsible for American forces in the vicinity of Hue. He was not sure of the situation in Hue but was aware early on January 31 that there was a need for reinforcements in the city. He ordered that Task Force (TF) X-Ray – located at the large US Marine base at Phu Bai, the closest US headquarters to the city – reinforce US forces in the city and relieve the besieged MACV compound. Brigadier General Foster LaHue, the assistant division commander of the 1st Marine Division and commander of TF X-Ray, was unaware of the scale of the attack in Hue, and thus responded by dispatching A Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment (A/1/1) to relieve the MACV compound.

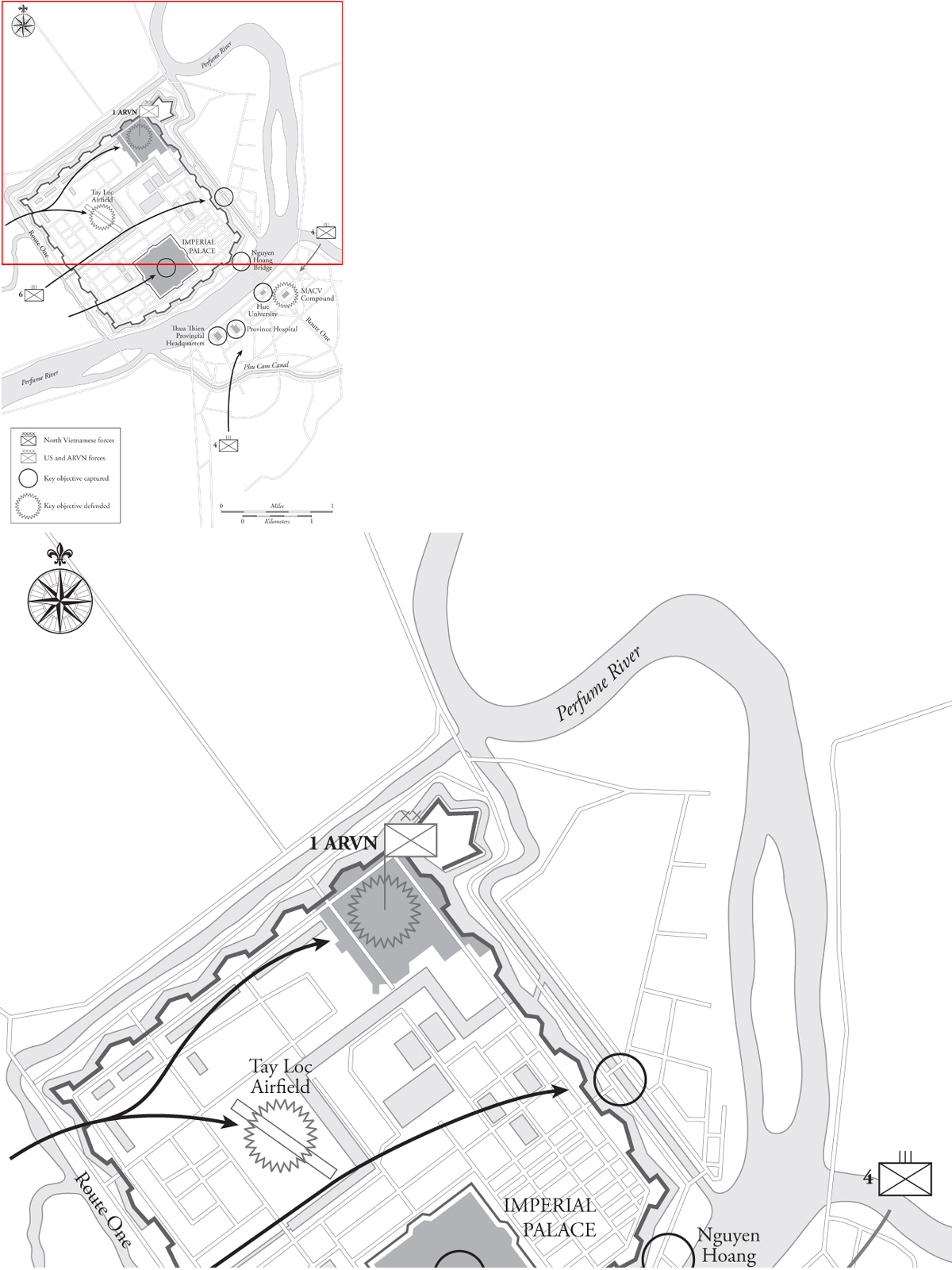

Map 5.2 The Battle for Southern Hue, January–February 1968

A Company, with no other guidance than to relieve the MACV compound, and no real intelligence as to the situation in Hue, loaded into trucks and moved up Highway One toward Hue, about 10 miles away. On the march to Hue the infantry company was joined by four M-48 tanks of the 3rd Marine Tank Battalion. Together the small task force moved toward Hue, encountering significant sniper fire, and occasionally stopping to clear enemy-occupied buildings along the road. As the company crossed the Phu Cam Canal and entered the southern part of Hue it was caught in a hail of rifle, rocket, and machine-gun fire. Advancing slowly and carefully the Marines dismounted and, working with the tanks, moved slowly against increasing resistance toward the MACV compound. Just short of the compound the company was pinned down by intense fire and the company commander was wounded. The company radioed Phu Bai for support.

Task Force X-Ray responded to the call for help from the Marine company in Hue by dispatching Lieutenant Colonel Marcus J. Gravel, commander of 1/1 Marines, his battalion headquarters, and G Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment (G/2/5) to reinforce A/1/1. Gravel, still with no specific knowledge of the situation in Hue, loaded up his Marines in trucks, and along with two Army M-42 “Duster” self-propelled dual 40mm antiaircraft guns, made the run to Hue. The Marine reinforcements linked up with A/1/1 and together the two infantry companies, supported by tanks and antiaircraft guns, pushed on to the MACV compound which they successfully relieved late in the afternoon. Upon reporting to X-Ray the success of the mission, Colonel Gravel was ordered to continue to attack north across the Perfume River bridge and link up with the ARVN forces fighting on the north side of the river. As medical evacuation helicopters arrived to remove the MACV and Marine wounded, Gravel ordered the relatively unscathed G/2/5 to continue while A/1/1, which had incurred significant casualties including all of its officers, was left to secure the MACV headquarters compound and the helicopter landing zone.

Gravel had gained an appreciation of the PAVN strength in Hue during his move to the MACV compound. Upon receipt of the new orders he protested, but was told to “proceed,” clearly indicating that the true situation in Hue was still not understood in Phu Bai. The company moved north from the MACV compound, fighting through enemy snipers until it reached the southern bank of the Perfume River. There G/2/5 encountered the Nguyen Hoang Bridge over which Highway One connected the old city on the north bank with modern Hue on the south bank. The Marine tanks, now joined by several M-41 light tanks of the ARVN 7th Armored Cavalry Squadron, deployed on the south bank and supported the rush of infantry across the bridge.

The Marines of G/2/5 proceeded across the bridge cautiously and were halfway across when the opposite bank erupted with fire directed at the exposed infantry. In the initial volley 10 Marines were killed or wounded on the bridge as the allied tanks returned fire, desperate to suppress the PAVN machine guns which covered the bridge. With the aid of the suppressive fires, Gulf Company pushed forward across the bridge while gathering its dead and wounded. On the far side of the bridge the Marines encountered the closely packed housing that surrounded the massive Citadel walls. PAVN fire increased as the Marines entered the labyrinth of buildings. Enemy fire came from all directions, front, flanks and even from the rear as the company attempted to advance. To Colonel Gravel it was obvious that a single infantry company was grossly insufficient for the task of attacking into northern Hue, and there was the very real danger that the company might be cut off and surrounded. On his own initiative he ordered the company to withdraw back to the south bank, itself a very difficult task to accomplish under constant and intense enemy fire. By 8pm the Marines were again consolidated on the south bank of the river. Gulf Company had managed to bring all of their dead and wounded back to the south bank in their withdrawal, but the attempt to cross the bridge was costly: 50 Marines had been killed or wounded on and around the bridge, a third of the company’s strength. As night fell at the end of the first day of fighting in Hue, the Marines were engaged, but they were outnumbered and the situation was in doubt on the south side of the river. Meanwhile, demonstrating the lack of understanding of the situation at higher headquarters, that same night General Westmoreland, commander of all US forces in Vietnam, reported that the PAVN only had three companies fighting in Hue and that the Marines would soon have them cleared out.

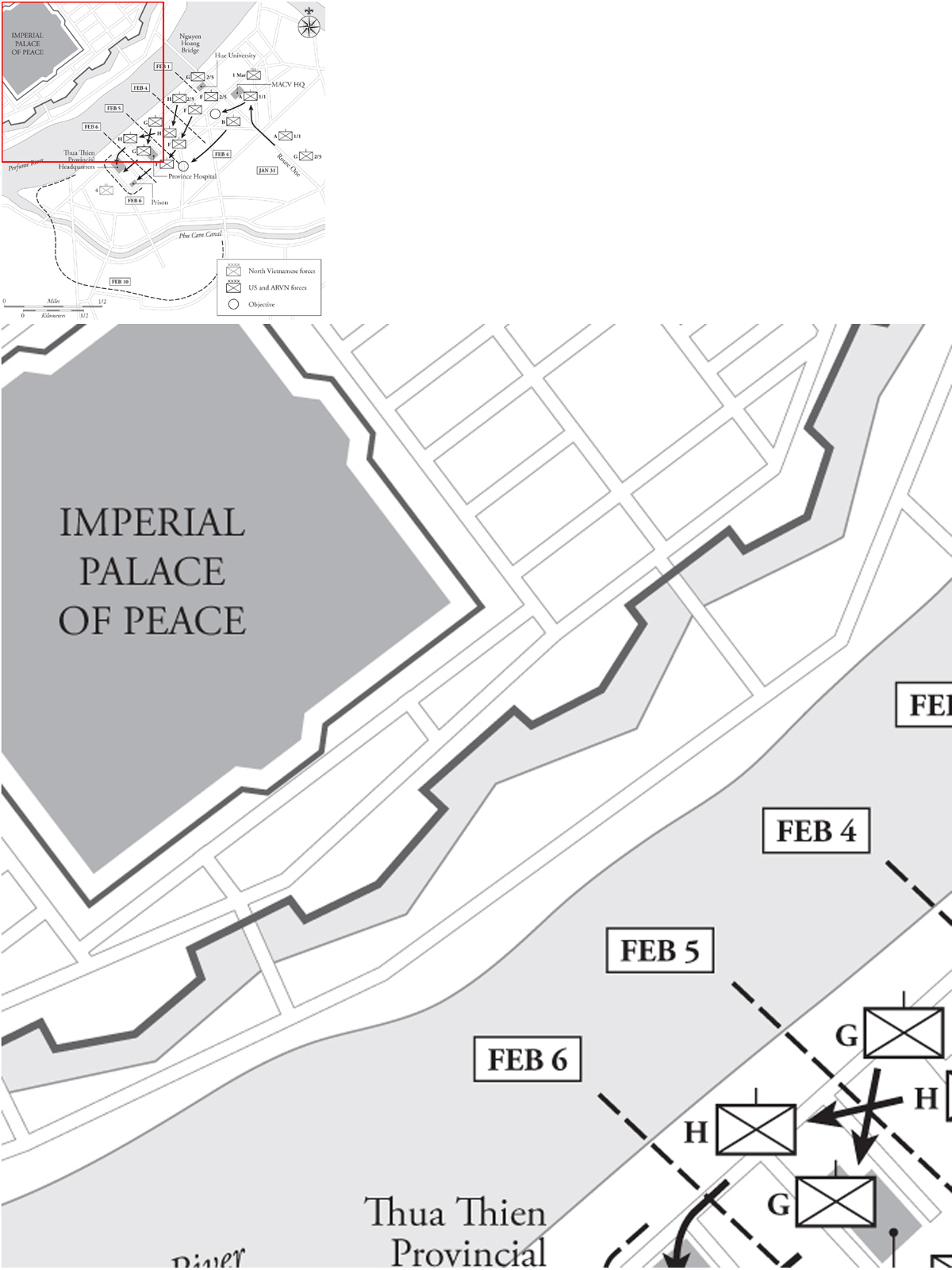

On February 1, the 1/1 Marines’ new mission was to attack west to secure the Thua Thien Provincial Headquarters and the province prison, six blocks from the MACV compound. The mission was assigned to G/2/5, commanded by Captain Chuck Meadows. The company, which had taken significant casualties in the failed foray across the bridge, now took on what appeared to be a simple six-block movement to rescue South Vietnamese forces still holding out in the provincial headquarters. However, the attack stalled immediately. Depleted by casualties from the day before, it took all the company’s resources to advance, one building at a time. Each building and each room in each building was defended by the enemy. A long, hard day of fighting, aided by the M-48 tanks, resulted in an advance of less than one block, and further casualties. That evening a third Marine company, Fox Company, 2/5 Marines, entered the battle and took over the advance from Gulf. In its first combat, Fox suffered 15 casualties and four dead in its lead platoon. As darkness fell Gravel ordered the attack to pause for the night. The Marines’ first full day in Hue ended in frustration.

On February 2, the third day of the battle, Hotel Company of the 2/5 Marines (H/2/5) arrived by convoy and was immediately assigned to join A/1/1 securing the university. Later, all four companies, including F/2/5 and G/2/5, expanded the secure base around the MACV and attempted to attack to relieve the prison. The attack failed when one of the lead platoons was immediately pinned down. That night the PAVN 4th Regiment counterattacked but was easily repulsed.

With four Marine companies in Hue, the headquarters of 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines (2/5), was ordered to the city. The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ernie C. Cheatham, and his staff, researched and attempted to acquire any and all types of munitions and equipment the battalion might need in urban warfare, having been previously engaged in jungle warfare. Cheatham found and read several field manuals which offered suggestions for conducting operations in cities. The night before moving to Hue the battalion acquired CS riot-control gas and protective gas masks for the battalion, loaded up its 106mm recoilless rifles and an abundance of ammunition, and the battalion’s 81mm mortars. The battalion also located large numbers of 3.5in. rocket launchers, known during World War II as bazookas. The weapons had been shipped to Vietnam but had seen little use and had recently been replaced by the lighter but less powerful Light Antitank Weapon (LAW). Cheatham’s officers picked up numerous rocket launchers and ammunition because the manuals indicated that it was an ideal weapon for busting through building walls.

On February 3, the 1st Marine Regiment Headquarters, under Colonel Stan Hughes, arrived in Hue to take over the battle, bringing with it Lieutenant Colonel Cheatham and the headquarters of 2/5 Marines. The 2/5 Marines took over the attack from 1/1 with orders to clear the city south of the river. Cheatham attacked west with two companies leading: H/2/5 on the right with its right flank on the river, and F/2/5 on the left sharing a boundary with A/1/1. The attack, however, made no progress. The attacks failed due to a huge volume of fire aimed at the two lead companies. The entire attack was further hindered by the requirement to keep the attacking companies on line. If H Company was successful in its attack but F was not, as occurred on the afternoon of February 3, then H Company had to withdraw because it had insufficient troops to both attack and cover its exposed flank.

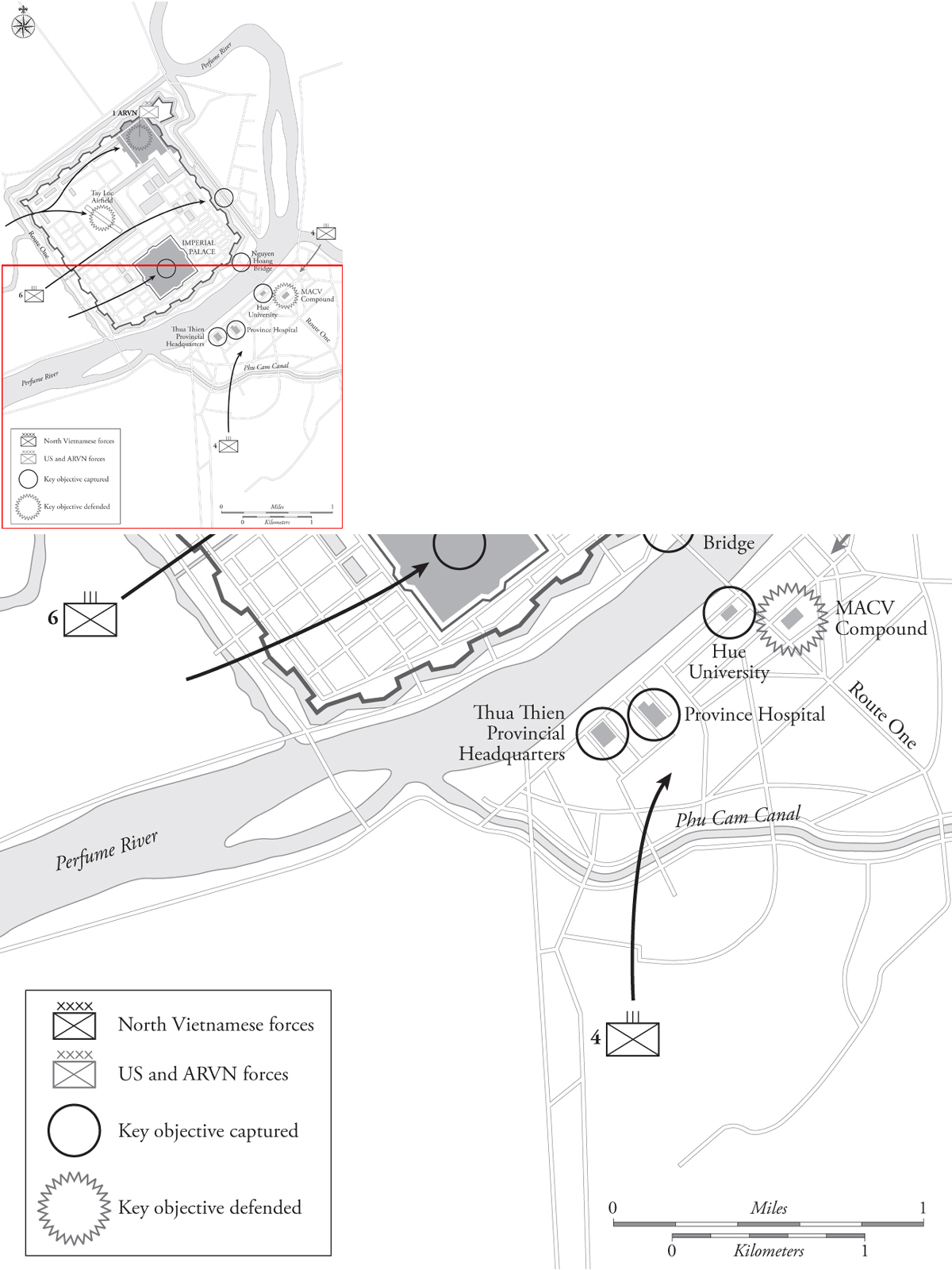

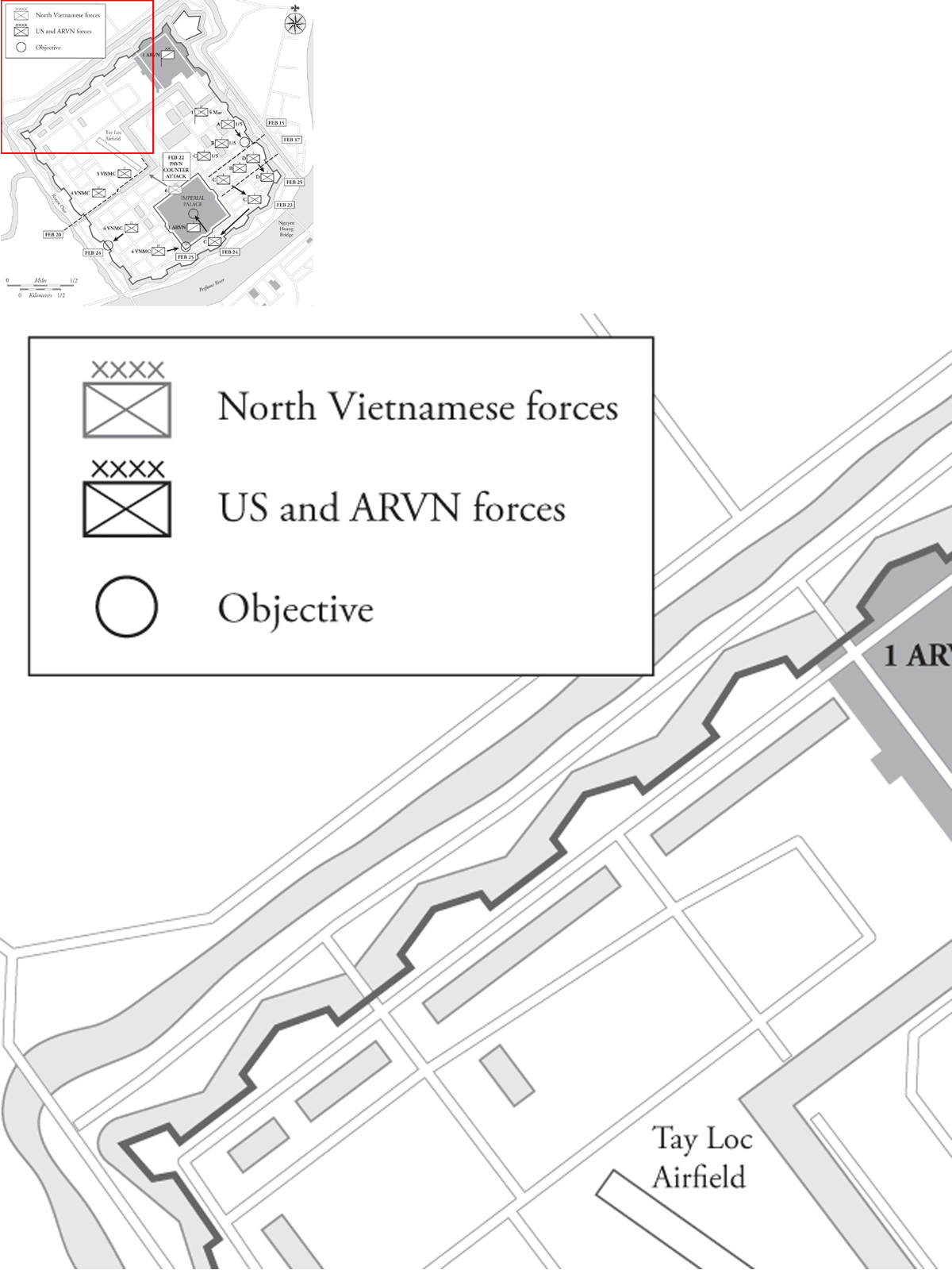

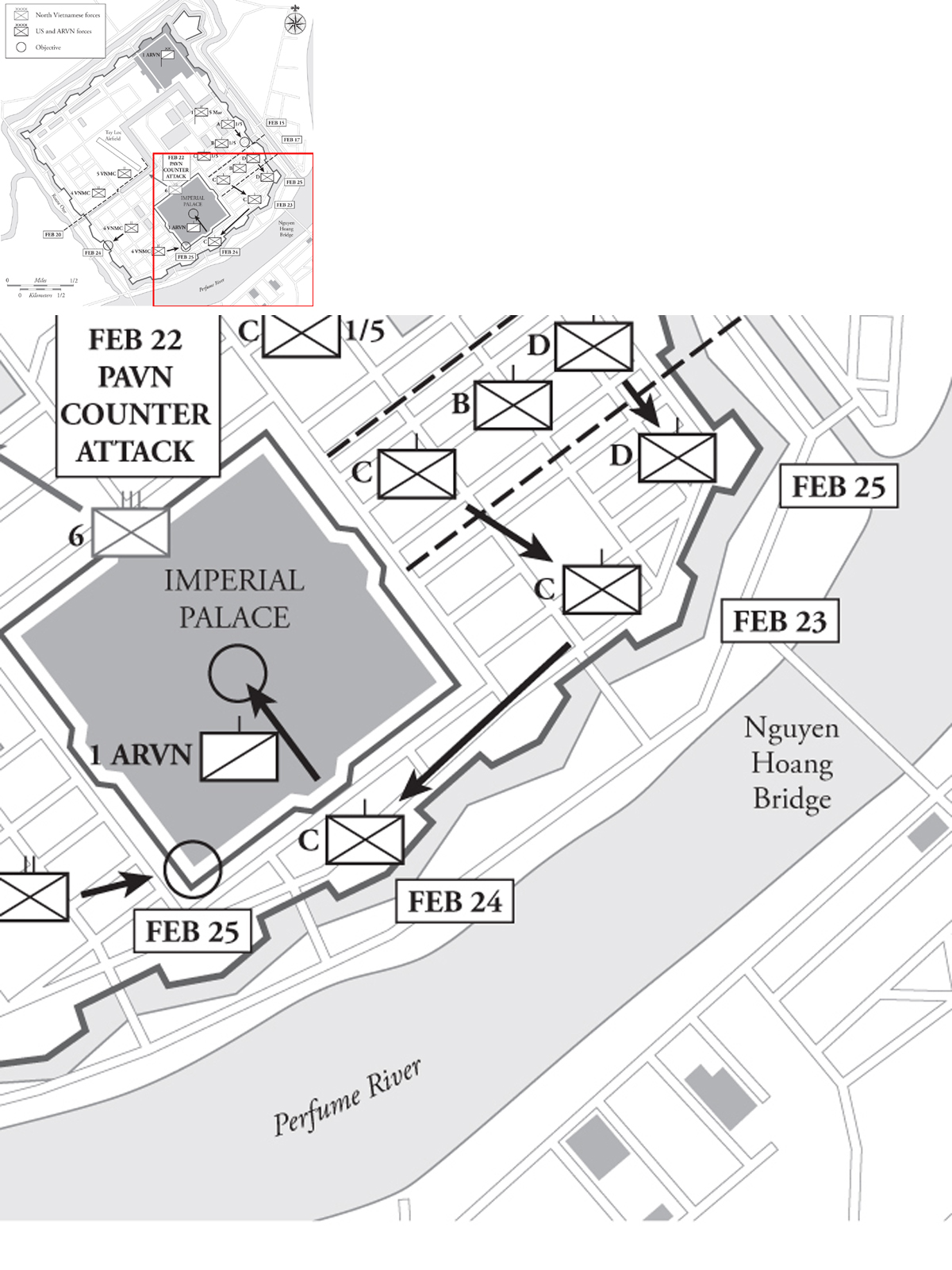

Map 5.3 The Battle for Northen Hue, January–February 1968

On the fifth day of the battle, February 4, the Marines south of the river began to make progress, and were achieving local superiority. At 7am the 2/5 Marines resumed the attack with H and F companies. The objective of the attack remained the provincial headquarters and prison, but the major obstacle in front of 2/5 was the government treasury building facing F Company. The treasury was a strong concrete structure with limited access, specifically designed to keep thieves out. Several attempts by F Company to get into the building on the previous day had failed. The renewed attack, however, made use of CS gas. The Marines positioned an M-38 gas launcher, capable of rapidly firing 64 30mm CS gas pellets, in front of the building and then doused the building with a barrage of CS. Tank and 106mm recoilless rifle fire then pounded into the building followed by a close assault by a platoon of Marine infantry wearing gas masks. Using fragmentation grenades and automatic rifle fire, the Marine infantry smashed through the front door and systematically cleared the large three-story building. Most of the enemy withdrew as the CS, against which they had no protection, wafted through the building. A few stragglers were killed by the Marines and the building was quickly secured. F Company’s success facilitated the advance of H Company, which captured the French consulate where almost 200 friendly civilians were taking cover.

Simultaneous with the 2/5 attack, A/1/1 attacked with support of tanks and captured the Saint Joan D’Arc school and church buildings. Late that afternoon, B/1/1 arrived by convoy in Hue, along with the last platoon of A/1/1 giving Colonel Gravel’s 1/1 Marines two reasonably fit companies (A and B) and the ability to attack alongside 2/5 and protect that battalion’s southern flank. In the course of the afternoon 1/1 consolidated its position around the school and church complex and in the process killed almost 50 PAVN troops. No-one in the unit had ever heard of inflicting 50 casualties on an enemy unit in a few hours in Vietnam; let alone have the bodies of the enemy strewn around their position as evidence. A Company also took two PAVN officers prisoner during the day.

The Marines continued the attack on February 5. In the previous four days they had covered two of the six blocks to their objective. Now several new factors came into play in favor of the Marines. Restrictions on the use of artillery and close air support fire were lifted as the higher headquarters gained a better understanding of the significant threat inside the city. The US Navy destroyer USS Lynde McCormick arrived offshore to provide naval gunfire support to the Marines. Most important, however, the Marines, who had no urban warfare training or experience, developed effective tactical techniques for fighting successfully from one building position to another heavily defended building position. Marine commanders were now adept at coordinating company and battalion mortar fires, suppressive small-arms and machine-gun fire, CS gas, 3.5in. rocket launchers, recoilless rifle and tank fire, and assaulting infantry into a carefully choreographed assault sequence that could systematically capture buildings and blocks of buildings with the fewest casualties.

On February 5, 2/5 Marines moved G Company into line on the right, setting up a three-company frontage that increased the combat power available to each company as it attacked. The attack began early and quickly captured a city block of ground in front of the battalion with little resistance. This brought the battalion in front of the Hue City Hospital complex of buildings, which civilians reported had been turned into a fortified position as well as serving as the regimental hospital for the 4th PAVN Regiment. Lieutenant Colonel Cheatham determined that, despite 1/1 Marines on his left flank not being able to keep up, he would continue the attack into the hospital. Cheatham’s men used all the techniques they had learned in Hue to systematically take down one hospital building after another. Now that the battalion had three full companies in the attack, it also had the capability of maneuvering within the blocks of buildings. Thus, the right flank company, Gulf, attacked first straight ahead, and then, once it had advanced forward of H Company, it turned left and attacked across the front of H Company. This not only took the enemy buildings from the flank, but it also cut off PAVN troops still in defensive positions facing H Company. F Company advanced slowly and bent its line backwards to deny the battalion left flank and remain linked to 1/1 Marines. By the end of the day, 2/5 Marines was one block from its objective, the Provincial Headquarters building and prison, and had all three of its rifle companies on line prepared to attack.

The morning of February 6 began with the companies of 2/5 Marines clearing and consolidating the buildings of the hospital complex which they had secured the previous day. Their objective – the block occupied by the provincial capital – had three major features: the provincial capital in the northern portion, the provincial prison in the middle, and more hospital buildings at the southern end of the block. The 2/5 companies were arrayed north to south: H, G, and F; with H and G having traded positions in the line as a result of the previous day’s cross-front attack. The penetration of the objective block began with F Company, which attacked the hospital building at the southern edge of the block as an extension of consolidating its positions. The southern portion of the block was not heavily defended but the company took several casualties from PAVN troops firing from the high prison walls which bordered the company’s right flank. With F Company set, G Company in the center bombarded the prison with mortars for over two hours, then breached the walls of the prison early in the afternoon and quickly overran the defenders. The final assault of the day was H Company’s attack directly through the front door of the provincial headquarters. The company preceded the attack with a hundred-round mortar bombardment of the building and 60 rounds of 106mm rifle fire. Then the building was liberally bombarded with CS gas. The lead Marine platoon then assaulted the building through the gas clouds wearing gas masks as the mortar and rifle fire ceased. Boards were used to cross over concertina wire strung around the building. Once inside the front door, the Marines quickly cleared the building using fragmentation grenades and rifles.

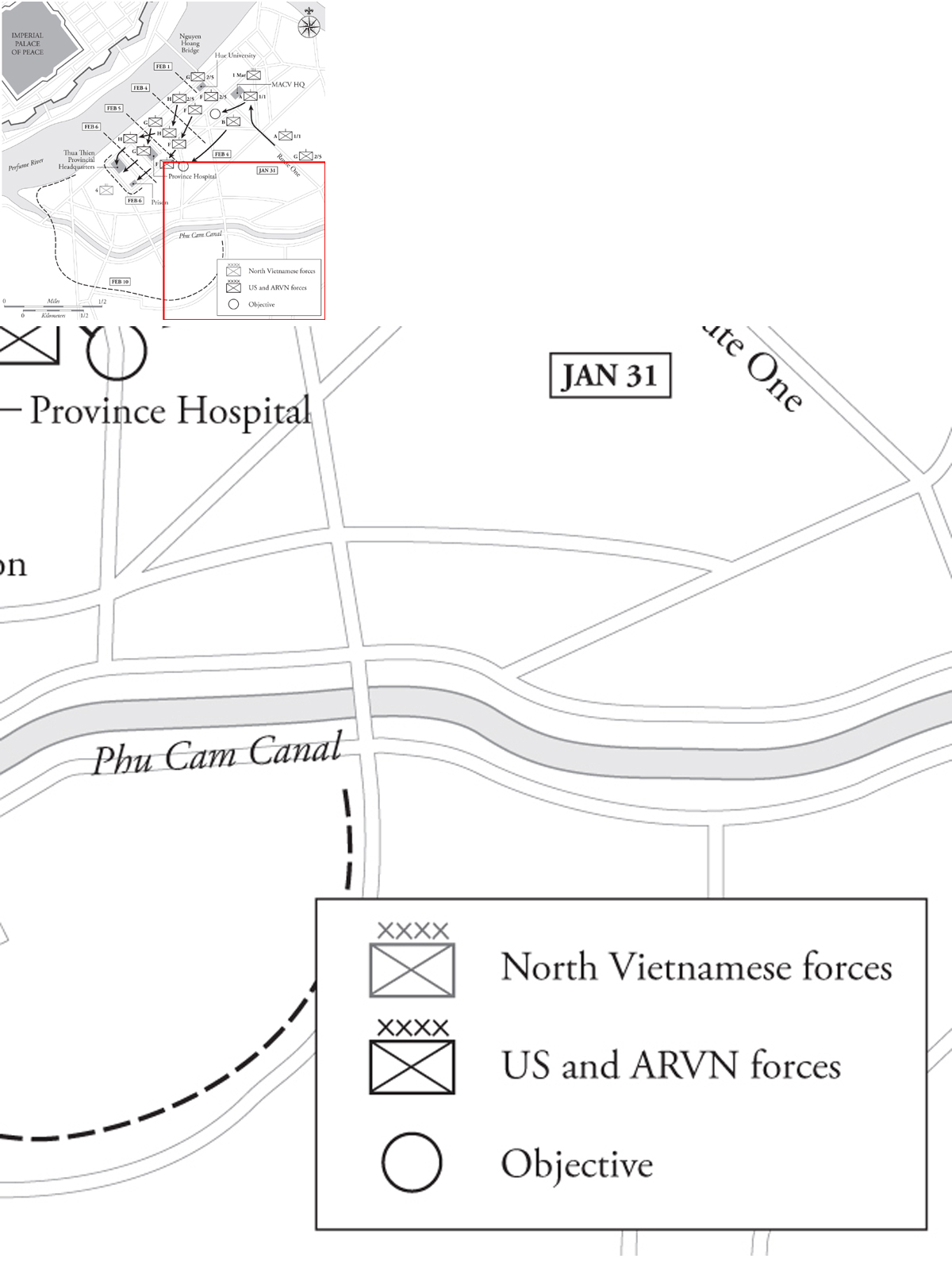

Following the assault on the provincial headquarters, the Marines tore down the Viet Cong flag flying above the building and replaced it with the stars and stripes. However, though the Marines would realize later that the day’s assault had broken the back of the 4th PAVN Regiment’s defense of southern Hue, it would require several days of dangerous clearing operations to confirm that the PAVN had given up the southern part of the city. By February 10, the southern part of the city was considered secured: the Marines had cleared the last of the PAVN snipers and rearguard, and recovered hundreds of discarded weapons, and tons of equipment. Thousands of Vietnamese civilians came out of hiding and a civil affairs collection and assistance point was set up by the US and South Vietnamese military to handle them. However, the battle for Hue was far from over, and attention shifted to operations north of the river.

While the US Marines fought systematically against the PAVN 4th Regiment for control of southern Hue, the ancient old city north of the river was the subject of an even more desperate contest between the ARVN 1st Division and the PAVN 6th Regiment. Like the PAVN 4th Regiment, the 6th was very successfully seizing most of its objectives in the early morning of January 31, but also like the 4th Regiment, the 6th failed to take the key military objective in the old Citadel part of the city, the headquarters compound of the ARVN 1st Division. This compound, like the MACV compound in the south, became the base of the ARVN counterattack.

General Truong was a shrewd military leader, who unlike many ARVN generals had made his rank and reputation in the ARVN through combat success and competence. He recognized that the most important terrain in the Citadel was his headquarters and immediately after beating back the initial PAVN attempts to capture it, he took steps to secure it completely against future PAVN attack. Toward this end he ordered that the division reconnaissance company and the division ordnance company, which were successfully defending Tay Loc airfield and the ordnance compound respectively, abandon their defensive battles and withdraw to reinforce the division headquarters position. He also immediately ordered his closest subordinate units, elements of the ARVN 7th Armored Cavalry Squadron, and the ARVN 3rd Regiment, to counterattack into the city. Further, he informed ARVN I Corps of the situation in Hue, and obtained operational control of the ARVN 1st Airborne Task Force, a group of three ARVN paratroop battalions. He immediately ordered these units to counterattack into Hue as well.

General Truong’s forces were a mixed lot of some of the best and some of the average ARVN military. The airborne units, and later the ARVN Marines who came under his command, were exceptional units. His own reconnaissance company and the armored cavalry squadrons were also very capable military units. However, his regular ARVN infantry battalions were modestly capable at best. At least one of his battalions was made up almost exclusively of new conscripts who were not completely trained. Though of comparable size to their US equivalents, the ARVN units were not nearly as robustly equipped and supplied. For example, the ARVN armored units were equipped with the M-41 light tank. The tank’s 76mm cannon and exposed .50cal. machine gun were not nearly as capable as the 90mm cannon and the protected cupola machine gun of the US Marine M-48 tank. More importantly, the US tanks could take numerous hits from virtually all weapons in the PAVN arsenal and continue to operate, while the M-41 was easily knocked out by the PAVN’s lightest anti-armor weapons. Thus, though individually very competent, and numerically sufficient, a lack of training, leadership, and equipment, meant that the fight to retake Hue was much more difficult for the ARVN division than for the US Marines.

Beginning on February 2, the ARVN 1st Division began to call battalions and regiments back to Hue to begin to organize the counterattack to recapture the city and destroy the 6th PAVN Regiment. The geographic objective of the ARVN attack was the Imperial Palace, located virtually in the center of the old Citadel. The first objective of General Truong was to secure the division compound area, which was the vital communications link inside the Citadel, and which they would use as a base for the assault to retake the city. On February 3, the ARVN began to attack to liberate northern Hue from the PAVN 6th Regiment. The first objective was the Tay Loc airfield which elements of the ARVN 3rd Infantry Regiment and the 7th Armored Cavalry Squadron were able to secure after difficult fighting. General Truong made clear to the ARVN I Corps, his immediate headquarters, that without reinforcements he would be unable to recapture the city. In response General Truong was reinforced with the ARVN Airborne Task Force, an elite unit which was the ARVN’s strategic reserve. The task force consisted of three small airborne infantry battalions, and General Truong assigned them to attack southeast from the ARVN 1st Division compound, along the old city’s northeast wall. Simultaneously, the ARVN infantry began to attack west and southwest from the vicinity of the Tay Loc airfield. The ARVN units in the north and west of the city were unable to make much progress, but the ARVN airborne infantry, the best of the ARVN, fighting against the more vulnerable elements of the PAVN 6th Regiment in the eastern portion of the city were able to make fair progress at heavy cost. By February 13, the Airborne Task Force had advanced about half the distance from ARVN 1st Division compound in the northeast corner of the city to the southeast corner of the city.

By February 12, almost two weeks since the initial attacks, the ARVN had recaptured about 45 percent of the Citadel. The ARVN battalions of the ARVN 1st Division were, however, exhausted, and severely depleted by casualties. The ARVN Airborne Task Force had likewise expended a significant amount of its strength. Both the South Vietnamese and the US commands agreed to provide reinforcements, particularly because the decisive fighting on the south side of the river appeared to be over.

The American command chose the 1st Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment (1/5 Marines) to reinforce the ARVN in the old Citadel portion of Hue. On the ARVN side, three battalions of Vietnamese Marines (VNMC) were identified to reinforce Hue. It took two days to move 1/5 Marines under Major Robert H. Thompson from positions in the field south of Ben Hua to northern Hue. The battalion had to cross the Perfume River on US Navy landing craft. The plan was for the US Marines to attack along the northeastern wall of the Citadel, relieving the Vietnamese Airborne Task Force, while the VNMC attacked along the southwestern wall. The wall itself was an ancient fortification that was up to 20 feet thick and flat on top. In places, the city had mounted the walls, and buildings occupied the top of the wall. The objective of both attacking forces was the walled Imperial Palace compound located in the center of the southeastern wall just north of the river.

The 1/5 Marines began their attack on the morning of February 13 and were immediately surprised when they were engaged by enemy firing down from the top of the Citadel wall as they marched southeast to relieve the ARVN airborne infantry. The Marines took casualties and immediately deployed into tactical formations and the lead elements of A Company attacked the wall. Subsequent to the successful, but costly attack by A Company, the Marines determined that the ARVN had pulled out of city during the night without coordinating, and the ARVN positions had been reoccupied by the PAVN 6th Regiment.

The beginning of the attack demonstrated the difficulty that the Marine battalion would experience in its attack. The old city presented more difficult tactical problems to the Marines than those encountered in the newer, southern part of the city. Buildings in the north were smaller, more numerous, and closer together. The streets were also much narrower. These conditions increased the cover for the PAVN, decreased the Marines’ options for maneuver, and made employing tanks and the Ontos recoilless rifle vehicles much more difficult. It took the Marines the entire first day of the attack to secure the original positions given up by the withdrawing ARVN paratroopers.

The casualties of the first day of the attack hit A Company the hardest, and as the attack began again on February 14, the battalion attacked with B Company on the left, wrestling with the dominating Citadel northeastern wall, and C Company on the right fighting along the outside wall of the Imperial Palace; A Company became the battalion reserve. From February 14 to February 17, B Company and C Company fought doggedly forward, achieving one hard-fought block a day. After four days of continuous fighting, the battalion was two-thirds of the way to the southwestern wall of the Citadel, only two blocks away. But the advance was costly. The battalion suffered tremendous casualties and the battalion, with permission from the commander of Task Force X-Ray, stood down to rest, replenish supplies and bring forward replacements.

The attack resumed on the night of February 20 with a large patrol from A Company infiltrating PAVN lines to occupy positions two blocks south along the southwestern wall. From there they directed artillery, mortars, and air strikes as the battalion attacked on the morning of February 21 with three companies abreast, D Company having reinforced the battalion during the pause in the attack.

The new attack was as slow, methodical, and fiercely fought as the previous week’s attack. The Marines continued to call on all the tools in their arsenal – tanks, Ontos, recoilless rifles, CS gas, artillery and close air support – and advanced one block a day. On February 23, the battalion achieved the southern wall and the northern bank of the Perfume River. The battalion then immediately turned right (west) and secured the gate to the palace. At that point the battalion halted as higher command insisted that ARVN forces be permitted to attack into the palace grounds. For the US Marines, the battle of Hue ended on February 23.

On the opposite side of the city, the VNMC attacked parallel to 1/5 Marines with the objective of securing the western portion of the Citadel and the Imperial Palace. However, the VNMC were having a hard time. Of the three VNMC battalions in Hue, one entire battalion was committed to securing the northwestern corner of the city where there were significant numbers of bypassed PAVN and Viet Cong units threatening the line of communications for the units attacking south. The three VNMC units had been moved to Hue directly from two weeks of hard fighting in the heart of the South Vietnamese capital city Saigon. En route to Hue they had replenished their supplies and received replacements, including hundreds of conscripts fresh from basic training. Thus, the VNMC units were much less experienced than the Americans. Like similar ARVN units, they lacked many of the heavy weapons employed by their American counterparts. Further, the VNMC units were supported by ARVN M-41 light tanks. The ARVN tank guns could not penetrate the concrete building structures of Hue and the tanks were easily destroyed by the standard PAVN B-40 rocket – of which the PAVN seemed to have an endless supply. Finally, in the VNMC zone of attack was the Chu Huu city gate, in the southwest corner of the city. This was the PAVN 6th Regiment’s line of communications and supply and therefore the regiment was determined to hold it against VNMC attacks at all costs. The result was that, similar to 1/5 Marines to the east, the VNMC battalions were unable to advance rapidly. Finally, as 1/5 Marines achieved the banks of the Perfume River on February 23, the PAVN and Viet Cong began to abandon the city. The VNMC quickly broke through the PAVN defenses and captured Chu Huu gate on February 24, sealing the escape routes of the remaining Communist forces. On February 25, the VNMC battalions secured the southwest corner of the palace walls and linked up with 1/5 Marines and ARVN units along the river.

The sudden collapse of the PAVN defense of Hue on February 23 and 24 was strongly influenced by the efforts of the 3rd Brigade of the US Army 1st Cavalry Division operating northwest of Hue along National Highway One. The Vietnamese and US high commands were slow to understand the situation in Hue and slow to react in a comprehensive way. Finally, several days into the battle, the magnitude of the PAVN attack was recognized and the higher command took steps to isolate the PAVN forces in Hue. The ideal force to isolate the PAVN in Hue was the airmobile units of the US Army, but in the midst of the nationwide Tet Offensive the highly mobile helicopter infantry were in great demand. The mission eventually given to the Cavalry was to not only isolate Hue, but also to ensure that Highway One north of Hue was clear. The Cavalry assigned the mission to one battalion: 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry, 3rd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division (2/12 Cavalry).

The 2/12 Cavalry airmobiled into a landing zone about six miles north of Hue. From there the battalion began moving south toward Hue parallel to Highway One. It had not gone very far when it began to take fire from a small village. The battalion quickly organized what it assumed would be a routine attack on the hamlet but when that attack was vigorously repulsed the American soldiers realized that they were encountering a large, well-organized enemy force. As the cavalrymen organized a hasty defense in an exposed rice paddy, only their firepower prevented them from being overrun. What the cavalry troopers had uncovered was the PAVN 5th Regiment, which was defending the Thung Front headquarters as well as guarding the supply route to PAVN forces in Hue.

Thus began a hard fight for dominance over the northwestern approaches into Hue. Initially, the numerically superior and well dug-in PAVN had the advantage, and 2/12 Cavalry almost didn’t survive the early part of the battle. However, 2/12 was able to establish a defendable position and then slowly the 3rd Brigade built up its combat power in the area. Eventually the brigade had five airmobile battalions deployed in a ring around the PAVN 5th Regiment and the Front headquarters. On February 23, the US Army began closing the ring only to find many of the positions completely abandoned. The Thung Front and the PAVN 5th Regiment had escaped the trap that the Americans were building, but in the process of making good that escape they abandoned the PAVN 6th Regiment and its attachments in Hue to their fate. Not coincidentally, on February 23 the Marines and South Vietnamese troops in Hue began making progress in attacks to secure the Citadel. Part of the reason for the collapse of the Hue city defenses was the cutting of their supply lines when the 3rd Brigade forced the retreat of the PAVN 5th Regiment.

Both the US forces and the PAVN demonstrated unique maneuver capabilities in the urban battle for Hue. The PAVN used a tried and true technique – stealth – on an unprecedented scale, while the US introduced a new maneuver technology: the helicopter. The initial success of the PAVN attack on the city was largely the result of surprise. The PAVN was incredibly effective at moving the equivalent of an entire infantry division through what was essentially hostile territory virtually onto the urban objective without being detected. This phenomenal achievement was the result of detailed planning, outstanding intelligence, effective tactical security to avoid detection, and patience. The result was that the PAVN was able to seize one of the most important urban centers in South Vietnam, almost without opposition, despite the close proximity of large ARVN and US military formations. The seizure of Hue by the PAVN is one of the great achievements in the history of urban warfare and demonstrates well the lesson that the best way to seize a city is to do so before it can be defended.

The most unique aspect of the American response was the employment of helicopters in the battle. Helicopters played numerous roles in the battle. The most important role did not occur until late in the battle with the airmobile maneuver of the 1st Cavalry Division’s 3rd Brigade into the area north of the city, completing the isolation of the PAVN forces in Hue itself. This capability, utilized late in the battle but achieving decisive results, represented a new way of introducing forces into an urban battle, and a quick way of achieving isolation of a city area. However, it is a technique that can incur significant risk. The 3rd Brigade almost suffered the loss of 2/12 Cavalry because the initial airmobile operation was conducted without sufficient intelligence regarding the situation on the ground.

The battle for Hue was not an inconsequential battle. It was an important battle in the Vietnam War in that it represented the strategic success of the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive. Like the larger offensive, the PAVN’s defense of Hue, though tactically unsuccessful, represented a strategic victory. The PAVN demonstrated, after three years of US intervention in the conflict, that it had the capability to capture South Vietnam’s third largest city and hold that city for more than three weeks against the best troops possessed by the United States and South Vietnam. That demonstrated the North’s capabilities, and also the ineffectiveness of US strategy to that point in the war. After the Tet Offensive, US strategic thinking increasingly focused on how to end the war, rather than how to win the war.

The battle for Hue also represented continuity in the nature of urban combat and perhaps signaled an increased importance for battle in cities. As important as any tactical lesson, Hue again demonstrated that at the operational level of war the most important aspect of urban warfare was isolating the city. Until the 1st Cavalry Division accomplished the isolation of Hue, the PAVN defenses remained strong. The battle for Hue also demonstrated that the tried and true conventional military approach to urban combat remained the same. City combat required aggressive small-unit leadership, an application of a wide variety of weapons types and techniques, and patient persistence. The US Marines, and to a lesser extent the ARVN and VNMC, systematically recaptured the city, block by difficult block. Urban combat in Hue also demonstrated that indirect fire and air support were important, and that armored firepower in the form of the main battle tank was essential to attacking in an urban environment.

The political lessons of urban combat were as important as the tactical and operational military lessons of the battle. Like Stalingrad, Aachen, and Seoul, the battle for Hue was dominated by strategic political considerations. The North Vietnamese understood the political strategic situation perhaps better than their opponents. The PAVN would not allow the 6th Regiment to withdraw from the city even after the expected uprising failed to occur and after it became apparent that US and South Vietnamese forces would destroy the regiment if it remained. The PAVN high command understood the immense psychological and propaganda value of the Viet Cong flag flying over the Citadel, the cultural center of both Vietnams, for weeks. The ARVN and US forces in the city began the battle at a tactical disadvantage because the city’s cultural value initially curtailed the use of air and artillery firepower. In the latter stages of the battle the US Marines were prohibited from finishing the battle due to the political need to demonstrate that victory was achieved by ARVN force of arms.

Hue was a turning point in Vietnam War despite being a tactical defeat for the PAVN. The battle was an indicator of an important trend in city fighting: strategic victory in urban combat may not be directly related to tactical victory on the street. In Hue the US Marines and ARVN won the battle on the streets, but the strategic battle of perceptions was won by the PAVN. Hue demonstrated that controlling a major population center, a city, for any significant period of time can be strategically decisive for a weak adversary and may lead to strategic victory even when combat power is insufficient for achieving that end.