The challenges of city fighting faced by the US military in Korea and Vietnam were difficult and tested the valor and ingenuity of soldiers and commands; yet, they were a confirmation of the type of urban combat that had originated in World War II. The veterans of conventional urban combat in Stalingrad and Aachen would have been very familiar with the combat environment in Seoul and Hue. However, the decades after World War II saw the rise of a relatively new type of war, “people’s revolutionary war,” and its application in urban centers around the globe. One of the first examples of revolutionary war practiced in an urban environment was in Algeria in 1956. There, the National Liberation Movement (FLN) was fighting a nationalist insurgency against the French government. In 1956 the insurgent leadership determined to move the main focus of the insurgency into Algeria’s capital and largest city, Algiers. The battle of Algiers, between the FLN and the French army in 1956 and 1957, was one of the first large-scale attempts by an insurgency to overthrow an existing government through operations inside a large city.

“People’s revolutionary war” was a theory of warfare formally developed by the leader of the Chinese Communist movement, Mao Tse Tung. Mao’s Chinese Communist movement began a struggle for power with their opponents, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kia-shek, in the 1920s. The Kuomintang was a powerful organization with a competent military arm and in the late 1920s it forced the Communists from China’s urban areas. For the next 20 years Mao organized and planned the return of the Communists as they nurtured their strength in China’s isolated mountains and rural areas. During the Japanese occupation of China (1933–45), the Kuomintang focused on China’s war with Japan. Mao and the Communists were given a respite to regain their strength. After World War II, the Communists led a revolt against the Kuomintang and ultimately defeated them in the Chinese Civil War in 1948.

During his decades-long struggle with the Kuomintang, Mao developed a theory of revolutionary war which guided his strategy. Mao’s theory of people’s revolutionary war was based on a political base of popular support. The strategy had three major lines of effort: political agitation, guerrilla warfare, and conventional warfare. These phases of the revolution also may be called the strategic defense, when a political base was established; the strategic stalemate, when limited military operations occurred; and the strategic offense, when the revolutionaries could revert to mobile conventional war. The goal of revolutionary warfare, the end state, was the replacement of the reigning government system with that of the revolutionary. In the first political phase of the theory the revolutionary force worked among the people establishing a base of popular support. This was the main effort of the revolutionary movement, and though the immediate priority of the revolution may later shift, Mao maintained that the revolutionary must always have the popular support of the people and thus political considerations and the political end state always guide operations, regardless of short-term priorities. Violence may occur during this initial phase but the aim was to support the buildup of popular support. After a political base was established, the revolutionary shifted to the guerrilla warfare phase. In this phase the revolutionary attacked the instruments of government power on a small scale without decisive engagement. Guerrilla operations had several objectives but the most important was to delegitimize the government and demonstrate its ineffectiveness. Secondary objectives in this phase included continuing to build popular support, train military members and commanders, and erode the military capability of the government. Once the military power of the revolution was sufficient the revolutionaries entered the third phase of the revolution, the strategic offensive, and directly challenged the military forces of the government on the battlefield. The final phase would result in the overthrow of the government and its replacement by the revolutionary leadership. This theory guided Mao’s strategy in his confrontation with the Chinese Nationalist government. Mao’s theory of revolutionary war inspired the strategy adopted by the Vietnamese revolutionaries under Ho Chi Minh, and it was the strategy that the Vietnamese pursued successfully against the French in Indochina. Many in the French military were thus very familiar with the writings of Mao, and some had even been exposed to the revolutionary war strategy while prisoners of war of the Vietnamese after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

After World War II, as most European powers were divesting themselves of their foreign colonial holdings, the French were interested in reasserting their traditional control over their overseas possessions. French policy was in sharp contrast with the aggressive nationalism that became popular in the former colonies during the war. The French compromised and bowed to independence movements in many of the colonies, most notably Morocco and Tunisia. However, the French government thought that it was in their interest to retain their colonial investment in Indochina, and the French believed that Algeria was not a colonial holding but rather an integral part of France. Therefore, the French government made a stand against nationalistic movements in both Vietnam and Algeria. In Vietnam the French faced a sophisticated Maoist insurgency that ultimately led to their military defeat at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. By 1955, French military forces were withdrawing from Vietnam and based on the Geneva Agreement of 1954, the temporarily independent states of North and South Vietnam were established by the United Nations.

At the same time that the Vietnamese were fighting the French in Indochina, unrest was occurring in French North Africa. Soon after the end of World War II, a political movement began among the Muslim population of the French province of Algeria to win autonomy from France. Because of its proximity to the French Mediterranean coast, Algeria had been established by the French not as a colony, but as an integral part of France. The major problem with this arrangement was that, though Algeria was a province of France, Muslims – who comprised 90 percent of the population – did not enjoy the full rights of French citizens. A small minority (about 10 percent of the total population) of European colonists in Algeria, known as Colons, did have full citizenship rights, and this minority ruled the province. Because of their position of power, the Colons had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Violence began in Algeria in 1945 and continued with increasing frequency and force for almost a decade. In late 1954 the FLN was in open revolt against French rule, and the capabilities of the FLN insurgents were too sophisticated and powerful for the French police to handle. In 1954 the French government began to employ the French army against the insurgents. For the first two years of the insurgency, the FLN fought the French army primarily in the hinterlands of the country. This strategy was classically Maoist. The rationale of the FLN was that insurgent forces could lose themselves in the difficult mountainous terrain and survive with the support of the friendly Muslim rural population. However, the problem with that strategy was that conducting hit and run raids against mostly military targets in isolated areas of the country had little or no political, military, or economic effect. In 1956 the political leadership of the FLN determined to change their strategy. They decided to move the focus of the insurgency nto Algiers, Algeria’s largest city, the center of the economy, and the capital of the province. The strategy envisioned attacking prominent public targets that French politicians, the French population, and the international community, particularly the United Nations, could not ignore.

The city of Algiers was the most important in the province. It was captured in 1830 when the French invaded Algeria, and became the center for all French operations in the region. In the 1950s the city had a population of about 900,000, of which two-thirds were Muslims and about 300,000 were Colons. The city was divided into a large new colonial city, and the Casbah. The modern city comprised perhaps 80 percent of the city area and was designed in a southern European architectural style. The Casbah was the old Muslim quarter of the city. It was positioned on the heights above the port and was small, covering approximately 1km2 (0.4 square miles), but housing over 100,000 residents. The buildings of the Casbah were stone, brick, and concrete, tightly packed next to each other, and three to five stories tall. Each building housed an extended family unit, and other relatives often lived in the neighborhood. Most of the Casbah was inaccessible to vehicles, the buildings being separated by steep narrow cobblestone lanes. The Casbah became the center of the FLN movement in Algiers.

The FLN organization in Algiers mirrored the larger FLN national organization and followed a classic insurgent cell structure. The FLN was organized in three-man cells with only one person having any knowledge of the larger organization and that person’s knowledge being limited to a single contact in the next higher organization. The FLN political leader in Algiers was Larbi Ben M’Hidi. Ben M’Hidi was also part of the national executive leadership of FLN. He was assisted by Saadi Yacef who was his executive for operations. Before the campaign against the French began in Algiers, Yacef took charge of preparing the Casbah as a base. His network of 1,400 operatives included bomb experts, masons, and numerous other special experts. Yacef purged the Muslim population within the old city of known French sympathizers. He also supervised the building of a network of hides and caches throughout the district. These positions were built into residences by creating false walls and tunnels that facilitated the storing of weapons and explosives, and the hiding and escape of insurgents during French army search operations.

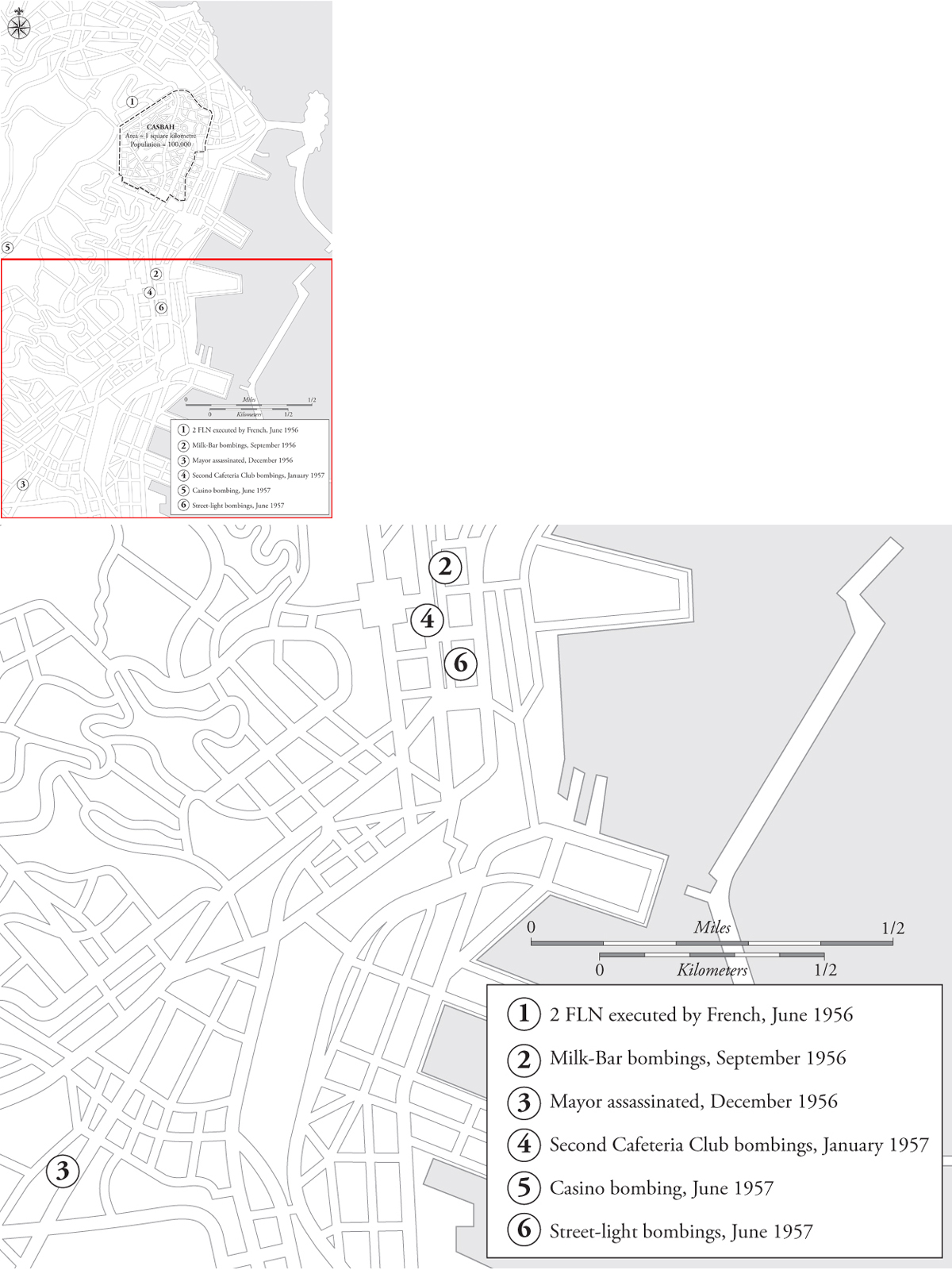

A chain of events precipitated the initiation of hostilities in Algiers. On June 19, 1956, two known FLN operatives were executed by the French for their involvement in the murder of several French civilians. The prisoners were executed by guillotine, and were defiant to the end. In sympathy with the executed prisoners, mobs of Muslims rioted throughout Algiers and randomly killed Europeans. This violence was encouraged by M’Hidi and the FLN. On orders from Yacef, FLN operatives roamed around Algiers and gunned down 49 French civilians in retaliation for the executions over a three-day period. This action was designed to build popular Muslim support for the FLN. The Colons themselves responded to the Muslim violence with a terrorist bombing of a suspected FLN home in the Casbah, which killed over 70 Muslims, most of them not associated with the FLN. The FLN then made a decision to begin a deliberate campaign of violence against the French civilian population in Algiers. The campaign had several purposes: to bring international attention to the grievances of the Muslim population of Algeria, to establish the FLN as the legitimate authority representing the Muslim population, and to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the French authorities.

The campaign began at the end of September 1956 with the most famous attack, the Milk-Bar bombing. The Milk-Bar attack was an unprecedented intentional assault on the civilian Colon community. The attack occurred on September 30, 1956, and consisted of three closely spaced bombings at businesses that catered to the young wealthy Colon population. Yacef used three female bombers to carry out the attacks. Two were 22-year-old law students at Algiers University. They were specifically chosen because they were all generally attractive, and most importantly somewhat European in appearance so could easily blend in with the European Colon population. Dressed in typical European style, the three left the Casbah separately. They met Yacef’s bomb-maker outside the Muslim quarter and were each issued their bombs. The explosions were planned to occur in rapid succession. The first occurred at the Milk-Bar, which was a youth hangout, and which was filled with mothers and young children drinking milkshakes at the time of the bombing. The second detonation followed within a minute, at the Cafeteria club, another favorite spot of young Colons. Together these two bombs killed three and wounded over 50, including numerous children. The third bomb, emplaced at an Air France travel agency, failed to go off because of a faulty timer.

Map 6.1 Major Events in Algiers, 1956–57

The bombings terrified the Colon community and received international attention. Yacef and B’Hidi determined that the bombings had achieved the type of success they desired: the European community distrusted and feared any Muslim as a potential terrorist. The Muslim community was on its guard against rampaging European mobs. The FLN determined to increase the terror campaign to further separate the two populations and in December they followed up the September attacks with the assassination of the civilian mayor of Algiers. The Colon community was outraged, and further angered when a FLN bomb exploded at the mayor’s funeral. Though this bomb did not cause any casualties, the funeral procession turned into a mob which rampaged through the city, attacking and killing any innocent Muslims they encountered. The FLN responded with more assassinations, and this finally drove the civilian governor-general of Algeria, Robert Lacoste, to take desperate measures.

In January 1957, due to the inability of the civil authorities to make any progress toward defeating or arresting the bombers and assassins, French officials turned government authority in Algiers over to the military commander of French forces in Algeria, General Raoul Salan. Salan promptly deployed the elite 10th Parachute Division to Algiers and gave the division commander, General Jacques Massu, the task of defeating the FLN organization in the city. Effectively, the civilian administration of the city was replaced by the military command of Massu.

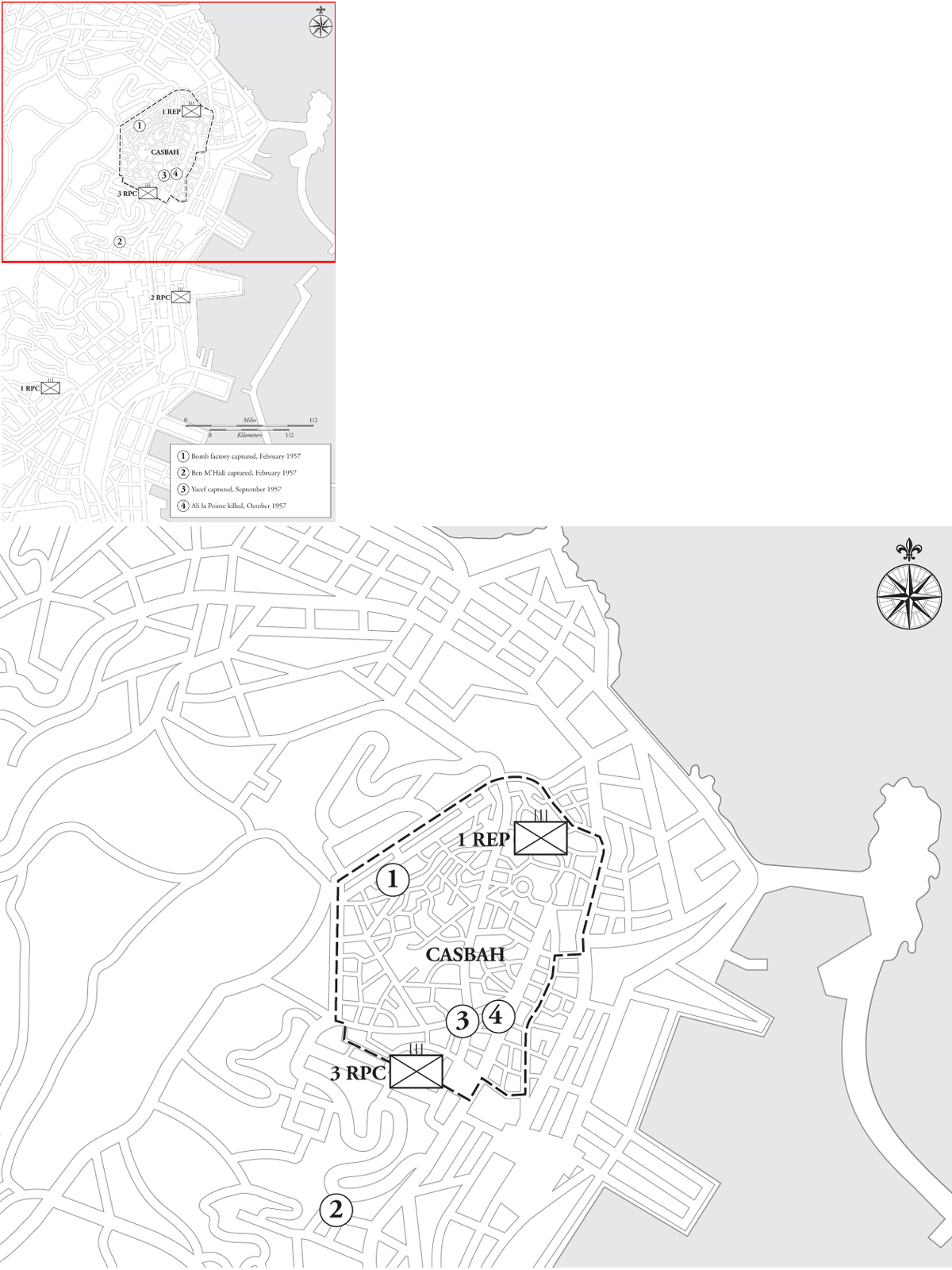

The 10th Parachute Division was a relatively new organization in the French army but one superbly manned, and experienced in the ways of counterinsurgency warfare. The division consisted of four parachute regiments, each about a thousand men strong: the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Régiments de Parachutistes Coloniaux (RPC), made up of French colonial troops, and the 1st Régiment Étranger de Parachutistes (REP), the Foreign Legion parachute regiment. The total strength of the division was 4,600 paratroopers. The division’s subordinate commanders and staff were some of the foremost counterrevolutionary experts in the French service, with extensive experience in the art of resistance fighting. Leading the 10th Parachute Division was General Jacques Massu, one of France’s foremost soldiers. He graduated from St Cyr and served on colonial duty in western Africa before World War II. During World War II he joined the Free French 2nd Armored Division and participated in the liberation of Paris. He was a founding member of the first French army parachute unit, and he served with the paras in Indochina. In 1956, at the age of 47, he was the first commander of the 10th Parachute Division and led it during the Suez Crisis in Egypt.

Massu’s staff were exceptionally experienced counterinsurgency experts. They were also ruthless fighters who recognized few limits in their efforts to defeat the FLN. Massu’s right-hand man was his chief of staff, Colonel Yves Godard. Godard was 44 years old at the time of the Algiers battle. In 1940, he had been captured by the Germans. After escaping German captivity on his third attempt, in 1944, he returned to Paris and then joined the French Resistance. Godard returned to the regular army in 1948, and was assigned to a secret intelligence unit, the 11th Shock Unit. He later led that unit to Indochina.

Godard had two outstanding assistants. One was 48-year-old Major Roger Trinquier. Trinquier was one of the originators of the “Guerre Revolutionnaire” doctrine, the French army’s answer to insurgency. He served in China from 1938 to 1945, and there became an expert on revolutionary warfare. Later, he formed the first battalion of colonial paratroopers, 1st bataillon de parachutistes coloniaux (1st BPC). He spent most of the years 1948 to 1954 in Vietnam, and most of that time he spent gathering intelligence and leading pro-French guerrillas against the Viet Minh deep in enemy-controlled territory. During the battle of Algiers he was a special deputy to Massu, and chief of the informant system in Algiers. Later he commanded the 3rd RPC and was subsequently recalled from Algiers for involvement in political agitation.

Massu’s other intelligence chief was Major Paul Aussaresses. Aussaresses served with Free French special services in World War II. During World War II he was imprisoned briefly in Spain, and participated in Jedburgh operations in occupied France and Germany. After World War II he formed the 11th Shock Unit, a secret intelligence and direct-action unit. He served in Indochina with the 1st RPC and conducted intelligence operations behind Viet Minh lines. He served in Algeria as an infantry brigade intelligence officer, in the 1st RPC, and as Massu’s special deputy for “action implementation.” Aussaresses was in charge of French interrogation efforts. Aussaresses left Algeria in 1957 and continued an uneventful military career in the army, eventually retiring as a general.

The four regimental commanders of the 10th Parachute Division were as impressive in their experiences as the staff. Colonel Georges Mayer commanded the 1st RPC. He was a graduate of St Cyr and one of the original members of the two airborne companies created by the French Army in 1937. He fought in World War II in Alsace and also in Indochina. Colonel Albert Fossey-Francois commanded the 2nd RPC. He was a literature student before World War II and joined the special services during the war. He had commanded his regiment, the 2nd RPC, in Indochina. Perhaps the most impressive of the parachute commanders was the 3rd RPC commander, Colonel Marcel Bigeard. Bigeard enlisted in the army before World War II, and was captured as a sergeant in the Maginot Line defenses in 1940. He escaped from the Germans and joined a colonial infantry unit. The army commissioned him as a lieutenant in 1943, and he joined the paratroopers and jumped behind German lines in 1944. As a major and battalion commander he jumped with the 6th BPC into Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel during the battle and became a prisoner of the Vietnamese when the command surrendered. Probably because of his reputation, the 3rd RPC was responsible for operations in the Casbah. The last of the para commanders also had a very impressive record. Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Jeanpierre commanded the Foreign Legion Parachute Regiment, the 1st REP. He served in the French Resistance during World War II, was captured by the Germans and spent the last year of the war in the Dachau concentration camp. Jeanpierre went to Indochina with the French Foreign Legion 1st REP and fought with them there until 1954. He was second in command of the 1st REP until March 1957 and was then appointed commander. During the battle of Algiers his regiment captured Yacef, and he was wounded during that action. Jeanpierre was killed in action leading his regiment in Algeria in 1958. Combined with Massu and his experienced staff, the officer leadership of the 10th Parachute Division was a formidable group. Their combined experiences and leadership made the 10th Para one of the most experienced, and most effective, counterinsurgency forces ever fielded.

At the beginning of the war, French forces in Algeria did not completely understand the nature of the enemy with which they were engaged. The initial actions of the FLN were viewed as criminal terrorism to be dealt with by the police. By 1956 the French government recognized the scale and effectiveness of the insurgency, and the French response was large but conventional military operations. These proved generally ineffective against the insurgency, which by then had been active for two years, was well organized, had a large popular support base in the Muslim population, and was skilled in conducting hit-and-run guerrilla operations. Beginning in 1956 the French started to adjust their tactics and operational approach. This was mainly due to the arrival in theater of experienced officers and troops from Indochina who understood the Maoist approach to revolutionary warfare. The new French leaders began to informally articulate a counterinsurgency doctrine known as guerre revolutionnaire, and the tactics, techniques, and procedures to implement it.

Guerre revolutionnaire was not a formally adopted doctrine of the French army. Rather, it was a counterinsurgency doctrine articulated by influential French officers and disseminated unofficially through discussions, and private and professional writing. The crux of the new doctrine was that the objective of the army was the support and allegiance of the people. This support had to be won by providing a promising alternative ideology to the population. That ideology was a liberal French democratic ideology with strong Christian overtones. The tactics that supported the French doctrine were in general very effective. These tactics rested on five key counterinsurgency fundamentals: isolating the insurgency from support; providing local security; executing effective strike operations; establishing French political legitimacy and effective indigenous political and military forces; and establishing a robust intelligence capability. The French doctrine demonstrated that they had a solid theoretical understanding of Maoist revolutionary war. The battle for Algiers was the first clear large-scale application of guerre revolutionnaire against the FLN.

The leaders of the French paratroopers, in particular the staff officers, knew that the most important key to successful operations against the FLN was intelligence. This was the primary responsibility of Godard, Trinquier, and Aussaresses. They quickly created a very sophisticated and robust human intelligence (HUMINT) system in the city. This system was multilayered, including local loyal Algerians, turned former FLN members, paid informers, and aggressive interrogation and detention practices. It was linked to strategic intelligence operations in France as well as to the intelligence operations of other nations – notably Israel. It was managed by the key division staff officers personally, and included unit intelligence officers in each regiment. The key to the success of the intelligence system was the rapid dissemination of critical information to strike units. The French standard was to strike at targets identified through their intelligence system within hours of uncovering the information. High-stress interrogation techniques and torture were an integral part of this system – and its major defect. The failure of the French to recognize this flaw had immense strategic consequences.

The French adapted their operations and tactics, techniques, and procedures in recognition of the importance of intelligence. They adjusted their organizations to ensure that the most competent and qualified officers were assigned to the intelligence positions. The intelligence staff positions became in effect the key operational staff positions in battalion-level organizations and higher. The French ensured that intelligence was linked tightly to mobile reaction units. They understood the fleeting nature of good intelligence and thus developed the ability to react to acquired intelligence quickly with their mobile units. The French recognized that human intelligence was most important. They built multiple, overlapping layers of HUMINT networks to provide and cross-check information. They also understood that the environment in which the insurgents operated was the population. The French army therefore sought to organize that environment. This took the form of a very detailed and accurate documentation of the population. Censuses were conducted and identification cards were issued that enabled files to be established on the civilian population and gave the army the ability to track individuals within the population.

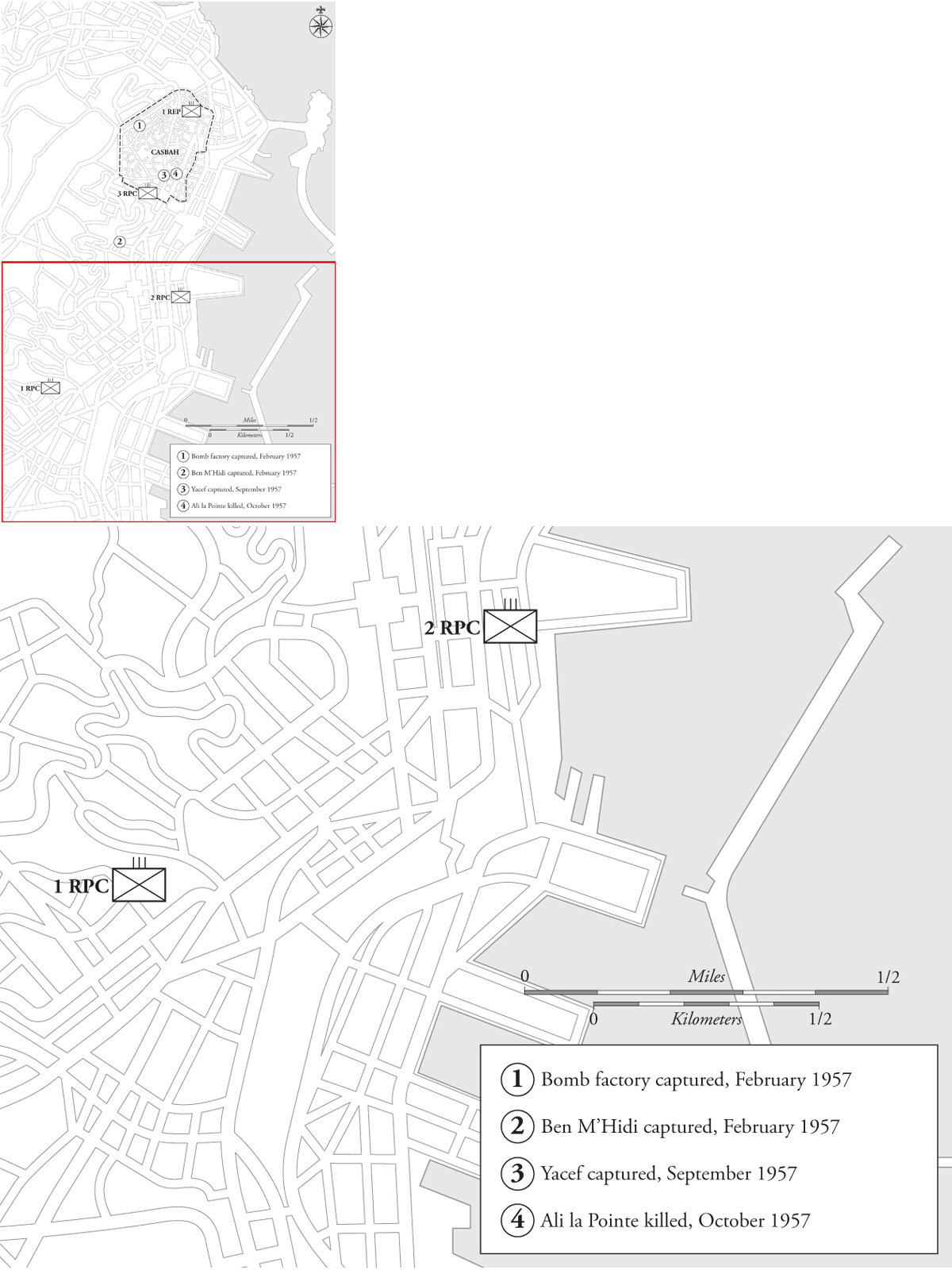

Tactically the 10th Parachute Division used the quadrillage system to organize the city. They divided the city into quadrants and assigned one to each of the four regiments. The regiments then became experts on the people and the layout of their assigned area. The regiments also controlled access to their quadrants through checkpoints and patrolled their quadrants constantly. The intent was to isolate each part of the city from external influence. The quadrillage system also ensured that nothing could happen of significance within the city without the paratroopers being immediately informed.

As each regiment took charge of their zone, their operating environment was carefully cataloged. The paratroopers went door to door and forced the population to submit to a detailed census which created a huge database of residents, their occupations, family, and addresses. This database was invaluable in subsequent search operations and interrogations. In addition, the physical layout of the city was studied. The paras established a coded organizational system for the unstructured Casbah. They mapped, and assigned each block and house in the Casbah a designation. The letter–number codes were then painted prominently on all the buildings. This allowed quick and accurate targeting of patrols and raids anywhere in the city and, combined with the population data, gave intelligence officers and commanders an accurate understanding of the human terrain of the battle space.

In the fall of 1956 the FLN established itself in the Casbah, built its organization, and prepared itself for operations. The Milk-Bar bombings and subsequent operations demonstrated the ability of the FLN to carry out campaigns. However, the real battle for Algiers began in January 1957 with the arrival in the city of General Massu and his division. The first contest between the paras and the FLN was the general strike action called for by the FLN in January 1957.

Ben M’Hidi believed that the bombings and assassinations had demonstrated the effectiveness of FLN operations within the city. They had also firmly driven a wedge between the European and Muslim populations of the city. What had not been demonstrated, however, was the extent to which the general Muslim population was under the control of the FLN. This, according to M’Hidi’s plan, was to be demonstrated by a city-wide general strike that would last eight days, beginning on January 28, 1957. The strike, timed to coincide with the beginning of the UN session in New York, would demonstrate to the Algerian population, the French, and to the world the willingness of the Muslim population to follow the FLN’s leadership, thus firmly establishing the FLN’s legitimacy. The strike would benefit the FLN’s case for Algerian independence to the United Nations.

Map 6.2 Deployment and Actions of the 10th Para Division, Algiers, 1957

The French completely understood the threat of the strike to the legitimacy of French rule in Algeria. Thus, the French government directed Massu to break the strike at all cost. On Monday morning, the first day of the strike, Muslim shops throughout the city remained shuttered and closed, Muslim children did not go to school, workers at the post office, the telegraph and telephone service, and the railroad failed to show up for work. It appeared that the strike was a total and complete success. Then the French army moved into action.

Massu ordered his paratroopers to deploy throughout the city, and each regiment quickly swarmed over its assigned sector. Armored cars hooked up to the fronts of the closed businesses and ripped the doors off their hinges. Shop owners were faced with the option of appearing and protecting their stock or having the local population pillage their stores. Once the owners showed up, paratroopers ordered them to stay open or be subject to immediate arrest. Fleets of trucks followed the paratroopers who began to systematically move through the Muslim neighborhoods and roust the population. Using their census data as a guide, working-age males were gathered, quickly organized by workplace, and then trucked to work under guard. Any who resisted were arrested, but faced with imprisonment by the French, most of the strikers – like the shop owners – reluctantly complied. Within a few days, the same tactics were used with schoolchildren. The French army literally herded the children from their homes to the schools. Thus, within a few days, the strike was broken, and the city, to all appearances was back to normal. The French, and importantly, the FLN, both recognized that the FLN plan had failed in a very dramatic and public way. Colonel Godard remarked that the FLN’s mistake was to declare the strike effective for eight days. Godard conceded that had the FLN called for a one- or two-day strike, it would have appeared to be very effective, and the paras could not have made their presence felt fast enough to claim a victory. As it was, the failed strike seemed to indicate that the French government still had effective control over the city and its population.

The strike was a major setback to the FLN in its campaign to demonstrate its claim as the legitimate representative of the Muslim population. However, it did not diminish the FLN’s operational capability. As an alternative to the strike action, Yacef supervised another bombing campaign. Two days before the strike began the FLN hit downtown Algiers with a patterned attack of three simultaneous bombings. The attack was designed based on the successful Milk-Bar attack. Three young women were chosen as the bombers. The targets were popular entertainment and eating establishments, including the Cafeteria club for the second time. This time all three bombs detonated killing five and wounded 60, including a young Muslim who was lynched on the spot by outraged mobs of Colons. Two weeks later, on a Sunday, young girls aged 16 and 17 planted bombs in two crowded sports stadiums that detonated and killed ten and injuring 45. Despite their success, however, it was getting harder and harder for Yacef and his organization to operate.

The FLN was forced to use women bombers because it was virtually impossible for a Muslim male to travel unchallenged anywhere in the city. The French army’s grip on the city grew tighter as patrols and checkpoints began to bring in more and more Muslims for questioning. Each interrogation was carefully conducted to create a picture of the FLN organization, and new information was quickly used to provide more focus for patrols, raids, and arrests. Careful police action at the scene of the bombings was also important. Police investigations led to the information that at least some of the bombers were women, and from that point on army and police checkpoints subjected all women to the same intense searches as men. Police investigation also led to the identification and arrest of the stadium bombers. Those arrests, and the arrests of several couriers by checkpoints and patrols, combined with intense interrogations, gave the French paras the leads they needed to begin to systematically track down and deconstruct the FLN network.

An example of how the French interrogation system worked is the capture of a locksmith working for the FLN. He was stopped and searched by a routine patrol of the 3rd RPC, and found to have bomb blueprints in his possession. He was then turned over to the division special interrogation branch. After three days of intense interrogation he gave away the address of Yacef’s bomb factory in the Casbah. However, with three days’ notice the FLN had time to break down the hidden factory and hide all evidence and the raid on the residence netted no results. A week later however the paras captured a bomb courier and the mason who built many of Yacef’s hides in the Casbah. Both talked under torture and they gave away the exact location of the primary bomb factory and the bomb-maker. Raiding paras managed to capture almost a hundred completed bombs, thousands of detonators, and hundreds of pounds of explosive. As important, they rounded up many of the FLN associated with the bombing network, and had positively identified names of most of the others. It had taken Yacef 18 months to create his network in Algiers but by the end of February 1957 it had been essentially destroyed by the French paratroopers.

The same intelligence that the paras used to track down the bombers of the FLN was also helping them close in on the leadership of the organization. By the end of January 1957 Yacef himself had barely eluded capture several times. On February 9, a top lieutenant of B’Hidi was captured. On February 15, the FLN leadership agreed that their campaign in Algiers was on the verge of failing and they determined that the political leadership should depart the city to avoid capture. They also decided to leave Yacef behind to continue the campaign as best he was able. On February 25, Ben M’Hidi moved out of the Casbah and into a suburb of the city. That move caught the attention of a Muslim informer in Trinquier’s network. The paratroopers quickly raided the home and captured M’Hidi in his pajamas. A little over a week later the French army announced that M’Hidi killed himself while in captivity. Most of the population of Algeria understood that the French army killed him. More than 40 years later, in 2001, Major Paul Aussaresses admitted in his account of the battle of Algiers to having shot the FLN leader.

The capture of M’Hidi, the retreat of the FLN leadership, and the loss of key operatives, safe houses, and the bomb-making network were major setbacks for the FLN. However, Yacef, the operations chief, was still at large and active. Through the spring of 1957, even as paratroopers were withdrawn from the city, Yacef laboriously rebuilt the damaged FLN network in the city. In June the FLN felt strong enough to strike back. The first attack was a four-bomb attack where the bombs were installed in the iron bases of street lights. The light casings enhanced the effects of the explosives and the bombs killed eight and wounded over 90 civilians. For the FLN, however, the attacks were a strategic mistake because the bombs, located in busy public places, indiscriminately killed Europeans and Muslims alike, and created discord in the Muslim community. This strategic error was not repeated a few days later when a massive bomb was exploded in Algiers Casino, an upscale entertainment venue catering to well-to-do Colons.

The casino bombing of June 9, 1957 killed nine and wounded 85. The bomb was placed under the bandstand and because of its positioning many of the wounded suffered leg amputations. Nearly half of the dead and injured were women. In reaction the Colon community went on a rampage through Muslim neighborhoods. Mobs broke into and pillaged Muslim businesses as police and soldiers stood idly by. The mob, estimated at over 10,000 in number, was finally brought under control by Major Trinquier who brandished a tricolor from his jeep, got their attention and led them to the French commander, General Salan. Salan addressed them and then ordered them to disperse, which they did. In addition to hundreds of businesses destroyed, five Muslims were killed, over 50 injured, and 20 cars burned. The casino bombing and the Colon reaction drove the two communities irrevocably apart and pushed the Muslim community into the arms of the FLN.

By the time of the casino bombing the various actions of the French had restricted the safe havens of the FLN exclusively to the Casbah. With the FLN again active, the para regiments were redeployed throughout the city, and a subordinate of Trinquier, Captain Leger, deployed a new intelligence asset into the battle. Leger, a member of the elite 11th Shock Unit and an Arab expert, recruited a group of former FLN members and deployed them into the general Arab working population, clad in the typical blue dungaree dress of the working class. These spies, known as Leger’s “Blues,” achieved astounding success as they mingled with their former associates and reported back to the French. The first success of the “Blues” was locating Yacef’s new bomb-makers. On August 26, they were both killed in a stand-off after being trapped by the paras in an apartment.

The French intelligence net, the “Blues,” and incessant patrols and checkpoints by the paras made it impossible for Yacef to operate. In late September a courier carrying a message from Yacef to the FLN outside of Algeria was captured by the French on an informer’s tip. The courier, under intense interrogation, gave the French the location of Yacef’s final hideout. On September 24, the house was surrounded by Colonel Jeanpierre’s 1st REP and a search revealed a hollow wall behind which Yacef was hidden. As the paras started to break down the wall Yacef threw a grenade out of a hole and wounded three paras including Colonel Jeanpierre. At that point Colonel Godard arrived and took charge of the operation. He ordered the entire house set for demolition and informed Yacef if he didn’t surrender they would blow the building up with him inside. At that point Yacef surrendered himself and a female companion. Neither Yacef nor his companion were tortured and, though sentenced to death by several military tribunals, Yacef was eventually pardoned by French President de Gaulle. Two weeks after Yacef’s capture, a “Blue” led the paras to the hideout of Yacef’s deputy, Ali la Pointe. On October 8, after fruitless negotiations, the paras blew up the house containing the trapped FLN assassin and two companions. The explosion set off secondary explosions in a bomb cache and brought down neighboring buildings resulting in the deaths of 17 innocent Muslims, including several children.

The capture of Yacef, the deaths of his bomb-makers, and the death of Ali la Pointe effectively destroyed the last organized elements of the FLN in the city of Algiers and ended the battle for the city. The battle was a clear victory for the French army over the insurgent forces of the FLN. One commentator at the time declared that the French victory was the Dien Bien Phu for the FLN. The French army, and the paras in particular, were the heroes of the Colon community and also of the French population in general. The political influence of the French army increased accordingly. The FLN, in contrast, was at a low point. The leadership had fled the country, the Muslim population was war-weary, and it was apparent that the military arm of the FLN was no match for the French army. However, though a short-term defeat, the battle for Algiers set the conditions for the long-term victory of the FLN. The battle focused French and international attention on the city and on French tactics used to defeat the FLN. As outsiders examined those tactics it became increasingly and alarmingly obvious that a cornerstone of French tactics had been harsh interrogation techniques; techniques many considered torture.

A major weakness of the French strategy was that it was based on the assumption that the primary ideological focus of the insurgents was Marxist communism. It did not account for an ideological motive based on indigenous nationalism and anti-colonialism. The ideological and spiritual nature of the conflict was internalized by many in the French army and became one justification for torture. They saw the enemy as communist and therefore as inherently evil. The struggle was one of ultimate national and ideological survival. This extremely ideological view of the war justified any tactical technique, regardless of its legality or morality, in order to achieve success. One French officer testified that young officers were told that the end justified any means and that France’s victory depended on torture. Many French army leaders believed that the extremely high stakes of strategic success or failure justified moral compromise at the tactical level.

Another justification for torture was that insurgent warfare was completely different from conventional warfare, and therefore required a different operating approach. In accordance with this view, the laws of conventional land warfare were considered inappropriate and counterproductive in the context of counterinsurgency warfare. The French also understood the primacy of HUMINT to successful counterinsurgency and they believed torture was an effective way to quickly get tactical intelligence information. This combination of perceptions led to the official condoning of torture.

A third justification for torture was that it was a controlled application of violence used for the limited purpose of quickly gaining tactical intelligence. Toward this end some French officers subjected themselves to electric shock to ensure they understood the level of violence they were applying to prisoners. What these officers did not understand was the huge difference between pain inflicted in a limited, controlled manner without psychological stress, and pain inflicted in an adversarial environment where the prisoner is totally under the control of the captor. They also failed to understand that once violence was permitted to be exercised beyond the standards of legitimately recognized moral and legal bounds, it became exponentially more difficult to control. In Algeria, officially condoned torture quickly escalated to prolonged abuse, which resulted in permanent physical and psychological damage, as well as death.

The official sanction of torture by French army leaders had numerous negative effects that were not envisioned because of the army leadership’s intensive focus on tactical success. The negative results of torture included a reduction in France’s ability to affect the conflict’s strategic center of gravity – the Muslim population; internal fragmentation of the French army officer corps; decreased moral authority of the army; the enabling of even greater violations of moral and legal authority; and providing a major information operations opportunity to the insurgency. The irony is that even though some tactical successes can be attributed to the use of torture, the French had numerous other effective HUMINT techniques and were far from reliant on torture for tactical success.

French doctrine and counterinsurgency theorists recognized at the time that the goal of the insurgents and the counterinsurgents, the center of gravity for both, was the support of the population. Despite this knowledge, many French commanders tolerated or encouraged widespread and often random torture. By one estimate, 40 percent of the adult male Muslim population of Algiers (approximately 55,000 individuals) were put through the French interrogation system and either tortured or threatened with torture between 1956 and 1957. This action likely irrevocably alienated the entire 600,000-strong Muslim population of the city from the French cause. The French did not understand the link between their tactical procedures and the strategic center of gravity.

French military operations in the city of Algiers in 1957 were extremely successful. By the fall of 1957 they had completely demolished the FLN network in the city. The major leaders of the movement were dead or captured, and the ability of the FLN to execute bombings and assassinations in the city no longer existed. This was accomplished through a very effective two-fold process. First, an exceptional intelligence system which systematically identified known and suspected terrorists and their associates and supporters. Second, a very effective response system which was able to act immediately and decisively on intelligence information before the FLN was aware of the compromised information. French tactics were undeniably effective. One French leader, who opposed torture, nonetheless conceded that without the systematic use of torture by the paras the battle could not have been won. That may be true, but the larger point, generally ignored by the French army leadership, was that with the torture, the war could not be won. After success in Algiers, the French expanded many of the tactics of 10th Parachute Division throughout Algeria. The results were similar: effective combat operations against the FLN while at the same time alienating the bulk of the Muslim population because of the widespread use of torture. Thus, winning the battle meant losing the war.

In 1962, as a result of very complex political factors, many of which can be related to the questionable tactics employed by the French army, Algeria gained its independence through popular vote sanctioned by the government of France. The European population quickly quit the country and mostly migrated to France. Thus, in 1962, as Algeria became independent, much of the FLN’s political success could be attributed to the French victory in the city of Algiers. As intended by the FLN, the battle focused the world’s attention on the war in Algeria and highlighted the position of the FLN to communities beyond Algeria’s borders. It also forced the FLN political leadership to abandon Algeria as unsafe. This move ultimately enabled them to wage their political campaign free from the threat of arrest or attack. Likewise, the battle of Algiers convinced the leadership of the FLN that a military solution in Algeria could not be won and this caused them to refocus and reprioritize their political efforts which were ultimately effective. Thus, though a decisive tactical defeat for the FLN, by winning the battle of Algiers, the French army set the conditions for the ultimate political victory of the FLN and the independence of Algeria from France.