The experience of the French in Algeria and the French and Americans in Vietnam indicated that following World War II a shift had occurred in warfare. Nuclear weapons made global war unthinkable. Instead two limited forms of warfare replaced the total war that typified global conflict. One was limited regional conventional war. This is the type of war fought by United Nations forces in Korea and on numerous occasions between various Arab nations and Israel. The other type of limited wars were wars of national liberation or revolution. This was the type of war that the French experienced in Algeria, and was also a component of the conflict in Vietnam. The French experience in Algeria, fighting the Algerian nationalist movement, the FLN, was very close to a pure Maoist revolutionary war. Beginning in 1969, the British Army, who had significant experience dealing with nationalist movements in the decades of imperial contraction after World War II, was faced with the challenge of a very unique urban enemy who was in many ways similar to the urban insurgents of Algeria. From 1969 to 2007 the British Army and other security forces were committed to a war with a variety of Irish paramilitary groups opposing British policy in Northern Ireland. The war was primarily fought in Northern Ireland, but occasionally spilled into England, and British military bases in Europe. The primary enemy was the Provisional Irish Republican Army, the PIRA, and affiliated or like-minded groups, operating with the goal of forcing the British Army out of Northern Ireland, and unifying Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.

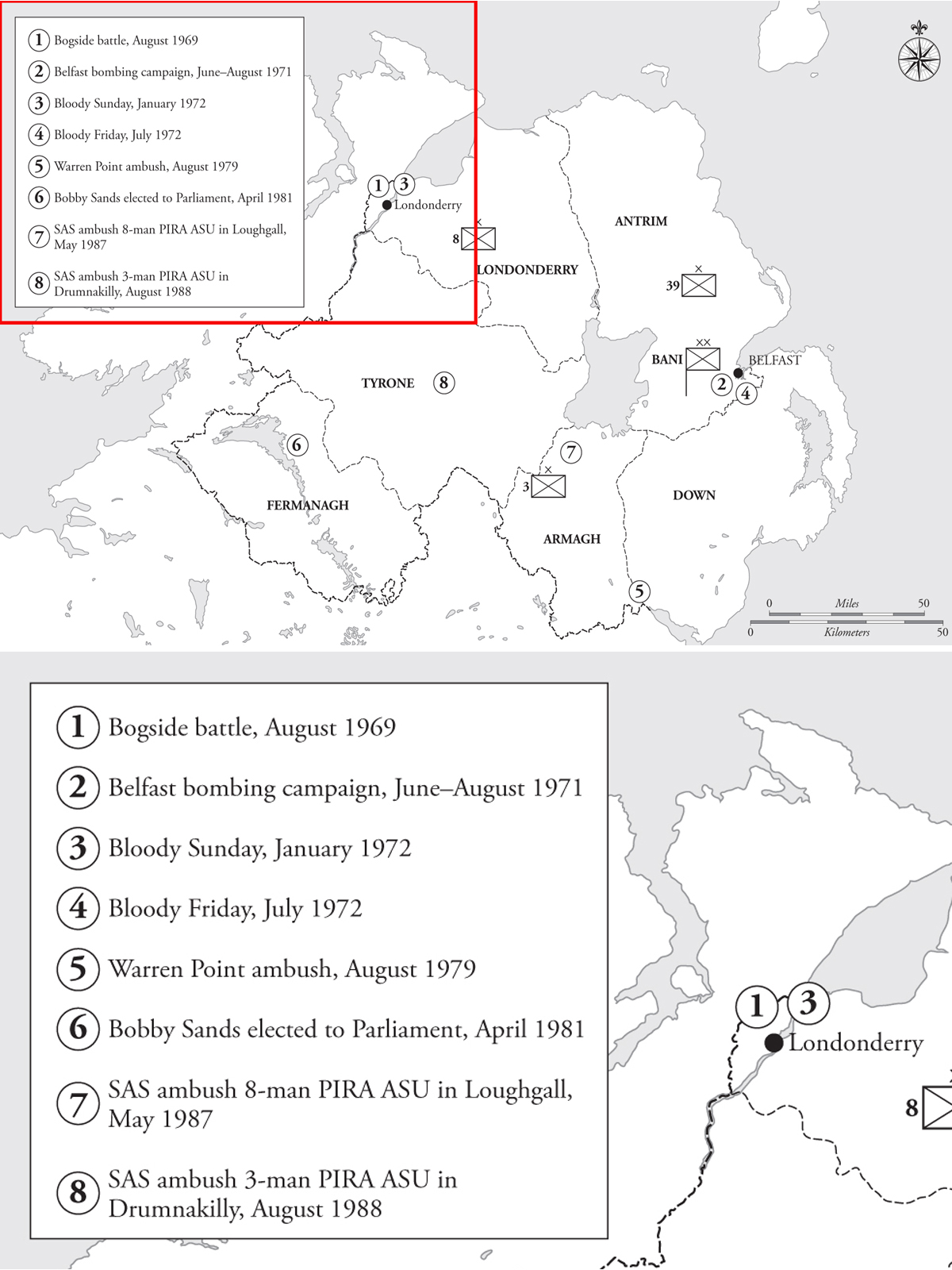

Ulster is the traditional northern province of Ireland. In 1922 six of Ulster’s nine counties were separated from the Irish Free State and formed into Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom. This shift was to protect the minority Irish Protestant community from Irish Catholic dominance. The majority of the population within the six northern counties were Protestants who emigrated to Ireland at the invitation of British government in the 17th century. The geography of Northern Ireland is classic green rolling countryside of farms interspersed with small villages and stands of forest. Several moderate-size cities are the focus of economic and political activity: the two largest being Londonderry, also known as Derry, and Belfast. The Atlantic Ocean marks the northern boundary while the Irish Sea does the same for the northeast and east. To the south and west, Northern Ireland shares a 220-mile border with the Republic of Ireland. To the west this border runs along the edge of County Londonderry and County Tyrone; to the south the border touches from west to east County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, and County Armagh.

The opponents of British policy used terrorist and guerrilla tactics and operated primarily in and amongst the civilian population of Northern Ireland. In 1969, when “The Troubles” began, that population was 1.5 million. At that time approximately 35 percent of the population was Roman Catholic while the balance was Protestant, primarily of the Presbyterian and Church of England denominations. By the end of the conflict the Roman Catholic population had increased to slightly over 40 percent of the total. The conflict was not about religion, but the religious affiliations of the population generally defined the opposing political views of the population, which were the source of conflict.

The Roman Catholic population was politically defined by two primary issues. The most important issue to the Catholic population was equal civil rights and opportunity. A secondary but also important issue was the unification of Northern Ireland’s six counties with the predominantly Catholic Irish Republic, which bordered Northern Ireland to the south and west. However, republicanism, supporting the political unification of Ireland, did not automatically equate to unqualified support to violent paramilitary groups. The dominant political characteristic of the Protestant population of Northern Ireland was the desire to remain an independent country within the United Kingdom (UK). In this relationship, Northern Ireland’s parliament was responsible for the internal affairs of Northern Ireland, while the national government in London was responsible for the international policy of the UK. Thus the major political issue separating the two parts of the population was unification with the Republic, advocated by “Republicans,” and loyalty to the United Kingdom, advocated by “Loyalists.”

The bulk of Northern Ireland’s population was located in the two major urban areas of Northern Ireland. Londonderry, the second largest city, had a population of about 60,000 in 1969, which had increased to about 85,000 by 2008, and was about 75 percent Catholic. Belfast, the largest city in Northern Ireland, had a population of 295,000 in 1969 and had decreased in population to 268,000 by 2008. The decrease in population was primarily due to flight of the middle class from the inner city to new suburban developments, and was not related directly to the violence. These two large urban areas represented about 20 percent of the country’s population, but were the scene of the largest proportion of the violence and military operations.

Operations by the British Army and allied security forces in Northern Ireland were greatly complicated by the multiple groups opposing British policy. The obvious and the primary enemy of the British was the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA). However, at various times other Irish republican groups were also active but not associated with the PIRA. These included the original Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), and the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA). The PIRA was formed in 1970 when it broke away as an organization from the IRA. The split was due to strategy differences within the IRA. The original IRA wanted to pursue the goal of a united Ireland primarily through socialist political action. The IRA members who formed the PIRA favored a strategy based on violent action to drive the British government out of Northern Ireland and force the Protestant population to submit to reunification as the price of peace. The INLA was much smaller and less capable than the PIRA and were focused on a radical Marxist political agenda as well as violence. The RIRA broke from the PIRA over the 1998 Good Friday Agreement which ultimately led to the end of British military operations in Northern Ireland. The small band of die-hard fighters in the RIRA continued to prosecute violence with diminishing capability after the Good Friday agreement into the 21st century.

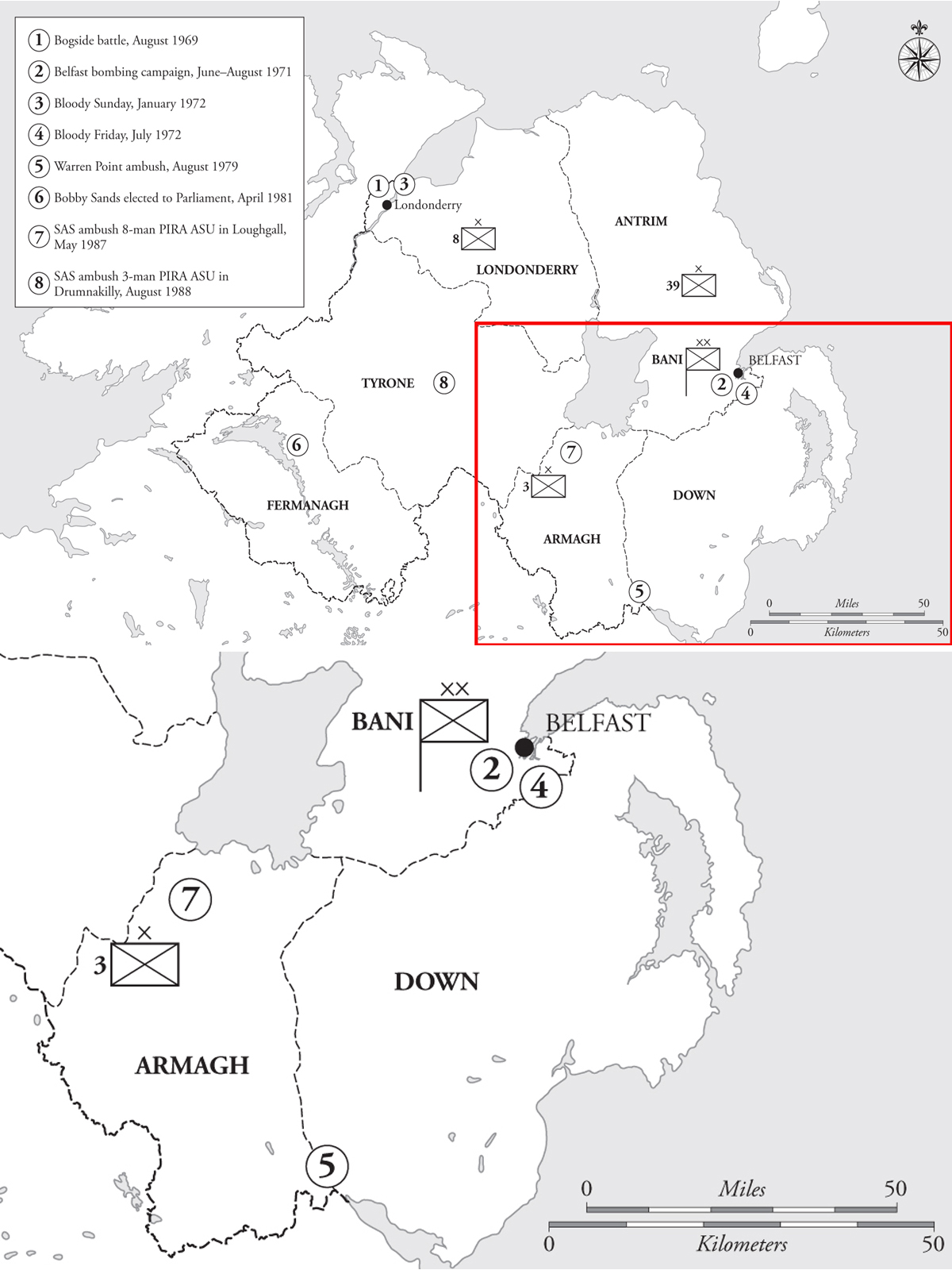

Map 7.1 British Army Deployment and Major Events, Northern Ireland, 1969–2007

In addition to the PIRA and similar republican groups seeking reunification with Ireland, there were also paramilitary groups who used violence to preserve the status quo. These groups included the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). The political objective of these groups was to preserve Protestant political dominance in Northern Ireland. They opposed any concessions or compromise with the Catholic community and the PIRA in particular, as a step toward ending Protestant political control and ultimately toward unification. In that their violence was not state-sanctioned and in many cases sought to thwart British policy, they were an enemy of the British security forces. However, because they did not generally target the army or security forces, and they were overall somewhat less violent than the PIRA, they were never the primary objective of military operations.

The British Army was the largest organization among several that the British government employed in its war with the PIRA. At its height in the 1970s the on-the-ground strength of the British military in Northern Ireland was approximately 28,000 troops. The army sustained a troop strength greater than 11,000 for most of the 38 years of the conflict. In the mid-1980s the army was organized into three brigades: the 8th Brigade was responsible for the western part of the country including the city of Londonderry; the 3rd Brigade was responsible for the rural area on the southern border in Armagh County; and the 39th Brigade was responsible for the northeast part of the country including the city of Belfast. The three brigades were commanded by Headquarters British Army Northern Ireland, located in the city of Lisburn, just outside of Belfast.

All units of the British Army were subject to operations in Northern Ireland, including heavy armored units and field artillery. The non-infantry units reorganized and retrained as infantry for duty in the country. Units that operated in Northern Ireland were deployed in the country in one of three statuses: roulement units which did short four-to six-month rotations into the country; deployed units which were stationed in the country for two year-long tours; and garrison units which were permanently stationed in the country. Roulement was the British Army term for short four- to six-month tours that allowed the army to quickly adjust the number of battalions in the country according to conditions. Units deployed in the country deployed with their entire compliment of soldiers as well as the soldiers’ families. There were also battalions on alert who could reinforce the forces already in the country within hours if an emergency developed. An important unique army establishment was the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). This force consisted of regular army infantry battalions, commanded by regular British Army officers, but manned by part-time local Irish army reservists. The eight battalions of the UDR were distributed throughout the country and operated as battalions under the command of the regular British Army brigades.

In addition to the army, the other major security force in the country was the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the country’s police force. When the conflict started, the force consisted of 7,000 personnel, which was a relatively small police force for the size of the population. Only about 3,000 members made up the full-time RUC, the rest being reservists. At the beginning of the conflict the RUC had three major components. The regular uniformed RUC did the bulk of the general policing and were the first responders to any type of riot, disturbance, or attack. The RUC Special Branch was the non-uniformed part of the force, responsible for investigations and police intelligence. Finally, in the early years of the conflict there existed a police reserve force known as the “B Specials.” This force was on call to augment the uniformed RUC in emergency situations. The B Specials were disbanded early in the conflict because of their lack of discipline. By the mid-1980s the RUC’s full-time strength was over 8,000 and it had another 2,000 officers in a reserve force.

Another important component of the army operating in Northern Ireland was the various special units which operated directly for army headquarters in Lisburn. The action component of this force was the Special Air Service (SAS), who were capable of conducting reconnaissance, surveillance, and combat operations against the paramilitaries. The British also formed special intelligence units in support of their operations. The first was the Mobile Reconnaissance Force. These forces were taken from the regular army battalions serving in Northern Ireland, but dressed in civilian clothes, and given some special training. They operated in support of the regular army battalions. Another special intelligence unit was 14 Intelligence Company. This company was formed by volunteers who received intense special training and worked undercover in Northern Ireland doing reconnaissance and surveillance. They operated only in civilian clothes and their operations were closely coordinated with the SAS.

“The Troubles” began in Northern Ireland in 1968 as a relatively benign peaceful movement led by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) advocating for civil rights for the Catholic minority. This movement was used as a vehicle by political activists including the IRA to promote their own broader agendas. However, in 1969 it remained a relatively peaceful protest movement that had, as its objective, fairly legitimate demands regarding Catholic suffrage and representation. A disproportionate response to the movement by Northern Ireland’s Stormont government eventually escalated the political movement to an armed clash between the paramilitaries and the British security forces. In the early years of this clash, 1968 to 1971, the British government and military pursued a peacekeeping strategy with the objective being to calm the emotions of both the Catholic and Protestant communities and quickly return the country to normal non-violent political activity. This objective failed due to hesitant decision-making by the national leadership, intransigence on the part of the Northern Ireland government, and poor decisions by the British leadership.

The civil rights movement began in late 1968 with several peaceful marches. However, in October 1968 a civil rights march was staged in Londonderry without a permit from the government. The RUC was on hand and broke up the march with water cannons and police reservists. In January 1969 a more substantial march was organized by the People’s Democracy group, a more radical student-based civil rights organization. That march was attacked by loyalist mobs while the RUC stood by and failed to intervene. Over 80 marchers were injured. Marches and violence continued through 1969. During that period, the non-violent civil rights movement was failing, the Stormont government appeared unable or unwilling to promote institutional reform, and the RUC were not acting to prevent violence, and in some cases instigated it, losing any legitimacy it had had with the Catholic community. Events culminated in the summer of 1969 with annual loyalist marches. In the summer of 1969 various officials warned that they would be provocative but they were nonetheless authorized by the government. The marches were seen as triumphal by the Catholic community. In August a march by loyalists in Londonderry was interrupted with rocks and bottles thrown by Catholic youths. The RUC intervened and pursued the Catholic mob into the Catholic Bogside neighborhood of Londonderry where the police were met by rocks, petrol-bombs, and barricades. Over the course of three days, riots spread from Londonderry to Belfast and the RUC’s resources were overwhelmed. The RUC responded to the riots with mobilized police reservists and all the weapons in their armory, including armored cars and machine guns. Loyalist mobs ransacked isolated Catholic communities, burning homes and forcing the residents to flee. As the violence escalated, the Stormont government was forced to call on London to authorize the British Army to support the police. On August 15, 1969, the army was ordered to Northern Ireland.

The British Army arrived in Northern Ireland with no strategy and little knowledge of the local situation. The Catholic community’s perception of events in the summer of 1969 was that it was being attacked physically by the loyalist majority, that the Stormont government and RUC colluded in the attacks, and that the likelihood of political reform was remote. The Protestant community’s perception of the situation was vastly different. Loyalists believed that the Catholic community and the IRA had embarked on the first step in a campaign to bring down the government, they also believed the Stormont government was ineffective, and local loyalist paramilitaries were the only alternative to stop the continued chaos perpetrated by the Catholics. The objective of British Army operations was to separate the two sides, to provide security, and allow local conditions to return to normal. The army was welcomed by the minority Catholic community and perceived as protectors of the minority from the large hostile Protestant mobs. The only problems with the British Army’s plan was there was no political strategy designed to remove the grievances of the minority community, and they were not legally neutral in the conflict – ultimately the army was legally and politically allied with the Stormont government and the Protestant majority.

To this point in the conflict, the summer of 1969, the IRA had not taken an active role in the violence that had occurred. That violence resulted in seven deaths and was perpetrated mostly by unorganized Catholic youth on one side, and much better organized loyalists, including the RUC, and the notorious RUC reservists, the B Specials, on the other. For their lack of involvement, the IRA was chastised and ridiculed by both communities. The slogan “IRA – I ran away,” was used to taunt the IRA. These events highlighted divisions within the IRA between those who saw the organization primarily as a political organization and those who saw it as an army. Ultimately, the latter group split from the original and formed the Provisional IRA, whose initial objective was to provide organized armed resistance on behalf of the Catholic community in response to the type of rioting that occurred in the summer of 1969.

For its part, the British Army was largely successful in bringing the violence under control through the remainder of 1969. Both sides respected the army’s presence, and the army established informal relationships with leaders in both communities in order to limit misunderstandings and achieve some cooperation toward a peaceful common goal. Checkpoints and army barriers were established to keep the two communities separate. Army operations concentrated in the most potentially volatile areas: Londonderry and Belfast.

As 1969 rolled over into 1970 it seemed that the initial deployment of the army was successful. However, the army had no control over, and little influence on, national politics in London, or even more importantly, with the Northern Ireland Stormont government. Though the army perceived its mission as a neutral peacekeeper between the two sectarian communities, in reality the reason for the army’s deployment was to support the police activities of the Stormont government. Thus, the army was legally not a neutral player but rather an extension of the British government, and, more important, also an extension of the sectarian Stormont government. This political situation quickly undermined the army’s position relative to the Catholic community as a protector of the minority.

Through 1970 tensions increased between the two Northern Irish communities. The Northern Ireland government was not able to reform to meet the legitimate demands of the Catholic community. The Catholic community protested the lack of reform. Protestant agitators pressed the government to meet protests with force. The British government refused to intervene decisively and in 1970 the British national elections brought in a new governing party with a more conservative policy toward the situation in Northern Ireland. Finally, the PIRA became active and assumed the role of protector of the Catholic community. In June riots occurred in Belfast in which the British Army did not intervene. The PIRA and Protestant groups got into a gun battle in which six people were killed. In response to the rioting and violence in Belfast the British Army imposed a curfew on the Catholic Falls Road neighborhood of Belfast and conducted extensive house-to-house searches for PIRA members and weapons. The searches turned up numerous weapons but were conducted in a completely arbitrary manner, destroying property and belongings, and totally alienating the Catholic community. The curfew and search broke the trust between the army and the minority community. In 1970 the PIRA began its first bombing campaign using homemade bombs to intimidate the Protestant community and register its displeasure with government policy. Numerous bombers were killed in the act of making and in placing the bombs. The bombing campaign was not very effective and bombing had not yet become the main weapon of the PIRA.

The sectarian violence escalated in 1971 as the PIRA took the offensive against the British Army and the Stormont government. The first British soldier killed in the conflict was shot by a PIRA sniper in February of that year. Through the year, the PIRA steadily stepped up attacks against the British Army and the Protestant community. Rioting broke out frequently in response to British Army searches for weapons and PIRA members. The confrontations between the British Army, the Catholic community and the PIRA became increasingly violent. Another deliberate bombing effort was made by the PIRA beginning in March 1971. This one was very effective. By August the PIRA had detonated over 300 explosive devices and injured over 100 individuals, most of them civilians. Over the course of 1971 the death toll steadily mounted: 88 civilians were killed; 98 suspected members of the IRA and associated republican groups died; 21 members of loyalist paramilitary groups were killed; and 45 members of the security forces (including the British Army and the RUC) were killed in operations.

PIRA operations began to take on a particularly brutal character in 1971. Catholic girlfriends of British soldiers were abducted and tarred and feathered. In March three young off-duty British soldiers were lured from a pub on the promise of attending a party and meeting girls. They were abducted, taken to a remote roadside, and executed by a pistol shot to the head. In December a prominent Protestant politician was assassinated in his home by the IRA. A concentrated PIRA bombing campaign in the summer of 1971 saw a series of 20 bombs detonated in heavily trafficked areas of Belfast over a 12-hour period. Not all of the violence, however, was waged by the republican paramilitaries. The loyalist paramilitaries were very active throughout 1971 as well, and on December 4 detonated a bomb in McGurk’s Bar in Belfast killing 17, and injuring another 17. It was the worst single bombing attack of the entire conflict and the target was not affiliated with the IRA. The frequency and brutality of the violence of 1971 led to one of the most detrimental and controversial operational decisions of the conflict: the British government’s decision to implement internment.

Political pressure from the Protestant civilian population on the Stormont government to take decisive action against the PIRA increased steadily and significantly throughout 1971. The options for the government were somewhat limited. The British Army and the RUC were already fully deployed and taking aggressive measures against the republican paramilitaries. The final option was the internment of suspected paramilitary members. This tactic – mass arrests and confinement of known or suspected PIRA members –had been used with great success against the IRA in the 1950s. The national government gave Stormont permission to use the British Army to execute internment over the objections of both the army and the RUC. The objections, however, were because of a lack of preparation rather than a policy disagreement. Thus, on August 9, 1971, the British Army and the RUC conducted raids all across Northern Ireland as part of Operation Demetrius, to arrest and detain without trial suspected members of paramilitary groups.

The internment policy failed both as a tactic and as a strategy for numerous reasons. Tactically the operation was largely a failure. The intelligence files outlining the organization of the republican paramilitaries were hopelessly out of date. Thus, very few of the 342 people arrested in the initial raids were actually active paramilitaries. The IRA claimed that virtually none of its people were arrested. Word of the impending raids had leaked and many paramilitary leaders went into hiding. Over 100 designated arrestees escaped the British net. No Protestant paramilitary members were targets, thus the raids appeared purely sectarian. The response of the Catholic community was completely unanticipated. All of Northern Ireland erupted in some of the most intense violence of the entire conflict: over 7,000 Catholics fled their homes; a few thousand Protestants did likewise, burning their homes to the ground as they fled; thousands of cars were looted and burned; hundreds of people were injured; and 24 people were killed. The death toll included two British Army soldiers, two IRA members, and 14 Catholic civilians and six Protestant civilians. A Catholic priest was shot and killed by the British Army as he was administering the last rites to a dying man in the street. Catholic relations with the British government and the Protestant community reached a new low. Over the remaining months of 1971 the violence continued unabated, and would increase in intensity into 1972.

The results of internment were even more devastating for British strategy in Northern Ireland. In addition to local conditions worsening, British policy was internationally condemned. Incarceration without trial, particularly erroneous incarceration, was offensive to Britain’s European neighbors. International support for the Catholic cause increased tremendously. Harsh interrogation techniques also brought international condemnation and accusations of torture and human rights violations from the international community. The Republic of Ireland was brought firmly into the conflict on the side of the Catholic community as over 2,000 Northern Irish Catholics fled as refugees across the border, and mobs in Dublin burned the British embassy to the ground. The internment policy brought almost no tactical gains to the British but caused huge tactical and operational problems as violence escalated. It also focused international attention and condemnation on the internment policy specifically and Britain’s overall policy in Ireland in general. Finally it became a rallying cry for the Catholic minority to further resist British and Protestant rule, and proved to be a huge boon to IRA recruiting and popularity among the Catholic population.

The conflict in Northern Ireland entered its fourth year in the midst of an accelerating cycle of attack and counterattack involving republican paramilitaries, loyalist paramilitaries, and the security forces, with the civilian population trapped between the combatants. While the violence accelerated, Catholic protest marches against the injustice of both Stormont and British policy continued unabated. These marches, however, had subtly changed in purpose. While in 1968 and 1969 their primary purpose was to highlight the legitimate grievances of the Catholic minority in a non-violent manner, they now became an important tool of the republican paramilitaries. The marches were designed to create confrontation with security forces. Under the cloak of these confrontations the PIRA could attack the security forces and provoke a violent response. This created the perception of a Catholic community closely tied to the IRA in common cause against the security forces, which gained for the PIRA the aura of defending the community against aggressors, and facilitated IRA recruiting.

The major confrontation between the British Army and the Catholic community over internment occurred in January 1972 and became known as “Bloody Sunday.” The event began as a Catholic civil rights march in Londonderry on January 30, 1972. British troops deployed to control and contain the protests, PIRA members were present within the protest group, and as violence escalated to throwing rocks at the army the army responded by opening fire. Control of the British soldiers, mostly members of the British Army elite parachute regiment, broke down and they opened fire on the crowd and killed 14 civilian protestors, of whom seven were teenagers. In addition 13 others were wounded by army fire. Extensive investigation of the incident could not provide evidence that the IRA fired on the British troops first, or that the marchers were unusually provocative. The event provided increased impetus to the sectarian division of the population and the intransigence of both sides. It also further increased the attractiveness of the IRA among the general Catholic population and perpetuated the cycle of escalating violence that began in 1971. Also, prompted by “Bloody Sunday,” the British government under Prime Minister Edward Heath lost confidence in the Stormont government to solve the security situation and reform the political situation. In March 1972 the British government dissolved the Northern Ireland parliament and installed direct rule of the country from London.

The IRA’s response to “Bloody Sunday” was “Bloody Friday,” on July 21, 1972. In an 80-minute period the PIRA exploded 22 bombs across Belfast, killing nine people and wounding 130. Most of the killed and injured were innocent civilians. The “Bloody Friday” bombings were part of an extensive bombing campaign that saw over 1,300 bombings over the course of the year. The response of the British government was Operation Motorman, designed to restore government control of and presence in Catholic neighborhoods which had been barricaded since 1970, and thus eliminate sanctuaries for the PIRA.

Operation Motorman was a massive military operation that involved 29 British Army battalions and over 25,000 troops. The army moved into Catholic neighborhoods in the early hours of July 31, 1972, against rock- and petrol-bomb throwing mobs. However, the size and speed of the operation rapidly intimidated the Catholic community and the British Army was firmly in control of the areas by nightfall. The IRA chose not to resist the operation and instead focused on ensuring that its leadership escaped capture. The British Army shot four people in the course of the operation, all in Londonderry, killing one known IRA member and one civilian, and wounding two civilians. During the course of the operation the army deployed several engineer combat vehicles to crush barricades. This was the only time during the conflict that the British deployed heavily armored combat vehicles to Northern Ireland. After opening up the Catholic neighborhoods, the army did not leave. Instead, it built protected patrol bases in the republican enclaves to ensure that the neighborhoods were firmly and permanently under government control. Operation Motorman was successful in permanently restricting the PIRA’s freedom of movement in Northern Ireland, eliminating what were sanctuaries from police and army interference and observation, and increasing the army’s and the police’s ability to gather intelligence. Notwithstanding the success of Operation Motorman, 1972 was the most violent year of the entire campaign with a total of 479 people losing their lives.

The PIRA response to Operation Motorman was increased violence and attacks against Protestants, the RUC, and the British Army. In response, the British Army stepped up its efforts against the PIRA, completing the transition from peacekeeping operations to full counterinsurgency operations. These operations, however, were not very effective. Though Operation Motorman made it more difficult for the PIRA to operate, it did not stop them. British counterinsurgency strategy was not adequate to the conditions in Northern Ireland. The type of counterinsurgency strategy with which the British Army was familiar called for a significant use of force and dramatic constraints on the sympathetic civilian community. Neither course was available to the army in the context of British Northern Ireland within the European community. Thus, British force was not sufficient to even curtail the operations of the IRA, much less destroy the organization, and the British Army was virtually powerless to intervene with the Catholic civilian community. However, enough force and interference with the civilian community occurred to ensure that the IRA retained the sympathies and support of the bulk of Catholics despite the tremendous number of innocent deaths that resulted from IRA operations. The violence continued through 1973 and 1974 – death totals in those years were 255 and 294 respectively.

Despite direct rule from London, little changed on the political front. After imposing direct rule the British government attempted to build a nonsectarian Northern Irish government based on power sharing between the communities. This effort was defeated by a combination of loyalist politicians, loyalist paramilitaries, and the Protestant-dominated trade unions. The Sunnydale power-sharing arrangement failed in the summer of 1974. The British Army’s failure to curb loyalist paramilitary violence, which claimed 209 lives in 1973 and 1974, as well as the army’s failure to intervene in the trade union strike of 1974, continued to confirm to the PIRA and the Catholic community that the army was a sectarian tool. British military operations were, however somewhat effective at disrupting PIRA operations and organizations. Casualties in 1975 to 1976 among PIRA operatives were 41 killed and numerous arrested. Total casualties on all sides including noncombatants in 1975 and 1976 were 260 and 295, indicating that despite the disruption caused to the PIRA, the two sides were locked in a deadly stalemate.

In 1975, the PIRA changed their strategy and determined to pursue a long war, in which they would attrite their adversaries over time until public pressure forced the British Army to leave Northern Ireland, and forced the Protestants to acquiesce to unification. As part of this strategy the PIRA reorganized into a cell structure as advocated by classic Maoist revolutionary war doctrine. These small units of four to 10 members were called Active Service Units (ASUs).

The British, however, were also adjusting. In 1976 they introduced their elite special operations forces, the Special Air Service (SAS), into operations in Northern Ireland. They also made a key decision in 1976 to change the security force strategy. Since the end of the peacekeeping mission, the British had pursued a classic counterinsurgency strategy in Northern Ireland that was primarily focused on securing the population and destroying the PIRA. Beginning in 1975 the British changed their strategy to one of police primacy. This shift was more than just moving the RUC to the fore of operations; it also included the end of internment, the beginning of civil trials and conventional imprisonment, political engagement with the Irish Republic to seek a political solution, back-channel talks with the PIRA, and the implementation of political reform.

The switch to police primacy, along with an increase in the effectiveness of the RUC, had some immediate effects as the PIRA was put on the defensive and their ability to operate was curtailed. Deaths resulting from PIRA attacks dropped dramatically beginning in 1976. However, it was not a long-term solution. The PIRA was still able to execute operations. Also, no important progress was made to separate the Catholic community from its tacit support of the republican paramilitaries. This was largely because of the continued sectarian nature of the RUC and British operations. No serious efforts were made by the RUC or the army to act against loyalist paramilitaries. In the years 1972 to 1979 the loyalist paramilitaries accounted for the deaths of 609 persons (as compared to 1,067 deaths caused by republican paramilitaries). In addition, the RUC was notorious for abusing prisoners with suspected ties to the PIRA. The RUC was widely believed to routinely beat confessions from those it arrested. Those confessions were then used to achieve long prison terms in court. Thus, the Catholic community remained estranged from the British government and continued to provide sanctuary for the PIRA. The lack of progress in Northern Ireland was one of many issues that contributed to a change in the British government in 1979 as the Labour Party, in charge since 1974, was replaced by the Conservative Party led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, marking the third change in government since the beginning of the conflict.

Margaret Thatcher’s government’s engagement with Northern Ireland began inauspiciously in May 1979. Even before the Conservative Party officially took over the reins of the British government, an INLA bomb killed the designated British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Airey Neave, in March. On August 27, the PIRA executed two of its most notoriously successful attacks of the conflict: a bomb assassinated Lord Louis Mountbatten, uncle of Queen Elizabeth II’s husband Philip; and a multiple bomb ambush in Northern Ireland killed 18 members of the British Army. These attacks confirmed the new British government’s commitment to a hard-line approach to Northern Ireland policy.

The inflexible approach of Margaret Thatcher’s government toward Northern Ireland policy became evident in the handling of the IRA prisoner hunger strike. The Thatcher government refused to consider giving in to republican prisoner demands to be accorded non-criminal special status. Beginning in March 1981, prisoners began to go on hunger strikes. The first hunger-striker, Bobby Sands, died in May. By the end of August a total of 10 prisoners had died. The British government did not give the prisoners political status, though by the end of the strike in October 1981, they had conceded on a number of demands. Though the British government conceded on several demands, the government declared victory over the hunger strikers; however it was a pyrrhic victory at best. The hunger strikers once again focused critical Catholic and international attention on British operations and policy in Northern Ireland. The strikers galvanized the Catholic community in much the same way as internment and “Bloody Sunday” had. The PIRA had widespread Catholic community support, such that Bobby Sands was elected to a seat in the British House of Commons from the district of Fermanagh and South Tyrone during his hunger strike in prison. That victory inspired increased political participation by the PIRA’s political branch, Sinn Fein. Sinn Fein’s increased role gave the PIRA a political strategy to accompany their military strategy that ultimately was characterized by the slogan “armalite and ballot box.”

The British political mishandling of the hunger strike strengthened the PIRA, however, in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, the British government somewhat redeemed its earlier policy misstep. The Anglo-Irish Agreement was an extremely important political milestone in the war between the Northern Irish republican paramilitaries and the British security forces. It established several important policy markers. First, it officially recognized a role of the Republic of Ireland in the future of Northern Ireland. Second, it firmly established that Northern Ireland was a part of the United Kingdom. Third, it recognized that the status of Northern Ireland would only change with majority consent. Finally, the agreement established a formal mechanism for joint Anglo-Irish government policy coordination on issues related to Northern Ireland. In the short term, none of these policy issues would make any real difference in the state of the war. They all would become important in the next decade.

In the short term the Anglo-Irish Agreement was important more for who opposed it than who championed it. It was vehemently opposed by the vast majority of Protestant residents of Northern Ireland. All the Protestant political parties opposed the agreement and widely condemned it to the public. Margaret Thatcher was condemned, and 200,000 Protestants rallied against the agreement in front of Belfast city hall. In addition, Protestant unions called a nationwide strike to protest the agreement, similar to the strike in 1975 that had doomed the Summerdale agreement. The PIRA, ironically, was also vehemently against the agreement. Their major objection was the fact that in the agreement the Irish Republic recognized British sovereignty over Northern Ireland. The objections of the Protestant majority and the PIRA to the agreement are important because they were ineffective. The RUC, backed up by the army, unlike in 1975, controlled the Protestant protest. The PIRA found itself isolated from the Catholic community in its opposition to the agreement. Catholics, both in Northern Ireland and in the Irish Republic supported the agreement as a major political step forward.

Though an important political achievement, there were no immediate changes in the tactical situation in Northern Ireland due to the Anglo-Irish Agreement. However, the effectiveness of security force operations increased dramatically through the 1980s. Though there were several attempts to resurrect army security primacy in the 1980s, the policy of the RUC leading security matters remained intact. This had two important results. It increased legitimacy of British security forces, at least in some important domestic and international audiences, if not among the Northern Irish Catholics. It also allowed the RUC to develop significant covert intelligence capability. This, combined with increased army covert capability, made it increasingly difficult for the PIRA to operate.

The British Army’s elite SAS was the major military action component in Northern Ireland beginning in the 1980s. The SAS first deployed to Northern Ireland in 1976, mostly as a political statement to demonstrate the resolve of the British government. In the 1970s one of the four squadrons deployed into Northern Ireland for six-month long tours of duty. In the 1980s the presence of the SAS was reduced to a troop of approximately 20 operators and the length of the tour was increased to a year. At the time of their initial deployment the SAS had no particular training in urban warfare, or integration into urban police operations. Their capabilities over the next 20 years demonstrated increased refinement, capability, and also the inherent difficulty of urban special operations, particularly in a policing environment.

In the 1970s the SAS suffered from a lack of good intelligence, but as RUC and army intelligence capabilities increased in the 1980s, so did the abilities of the SAS to launch effective attacks. Though most of the SAS operations were passive surveillance or backup to RUC arrest operations, they launched a significant number of arrest operations on their own and also several spectacular ambushes. The number of arrests made by the SAS is unknown because in arrest operations the SAS quickly handed captured paramilitaries over to the RUC and thus their role went unrecorded. However, action operations in which the SAS engaged the PIRA could not remain covert. In the 1970s, in several encounters with the PIRA, the SAS killed six paramilitaries while losing none of its own. In the 1980s, with a much reduced presence in Northern Ireland, the SAS lost two of its own operators and killed 26 paramilitaries. Its most intense ambushes were in 1987 and 1988. In May 1987 a heavily armed eight-man PIRA ASU was ambushed in the process of bombing an RUC police station in the village of Loughgall. All eight paramilitaries were killed while several soldiers were injured as the bomb severely damaged the police station. In March 1988, an SAS unit killed all three members of a PIRA ASU as they were preparing to bomb British headquarters in Gibraltar – the only direct confrontation between security forces and the PIRA outside of Great Britain proper. Later that same year another three-person ASU was ambushed by the SAS near the town of Drumnakilly in Northern Ireland. The SAS remained active in Northern Ireland in the first part of the 1990s and accounted for 11 paramilitaries with no SAS casualties.

One of the reasons for the success of the SAS in the 1980s and 1990s was the creation of a specialized intelligence unit for Northern Ireland: 14 Intelligence Company. This unit was created specifically to operate in the urban environment in Northern Ireland, its members were highly trained special surveillance specialists carefully selected to blend into the urban population. The operatives of 14 Company included older individuals and women, to increase their ability to avoid suspicion. The activities of 14 Company were coordinated with the SAS under one command called Intelligence and Security Group Northern Ireland. The command operated directly for the British military command in Northern Ireland. Though the damage done to the paramilitaries by the SAS and 14 Company was significant in terms of members killed and captured, perhaps the greatest damage done was psychological. The SAS was a formidable foe and paramilitaries were increasingly aware that at any time and in any place they might be under surveillance and targeted by British military special operations capability. This inspired increased caution, and internal security measures which greatly inhibited the paramilitary’s ability to conduct operations.

Though able to conduct some very significant operations in the 1980s and 1990s, including the highly disruptive bombing of the London financial district, the PIRA was increasingly on the defensive. Its ability to inflict casualties reflected this. Casualty rates steadily decreased in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly among security forces. There were two reasons for the decreasing PIRA effectiveness, particularly as the conflict entered the early 1990s. One reason was the effectiveness of the RUC and to a lesser extent, the British military and national intelligence services, to infiltrate informers into the republican paramilitary groups and to turn existing members of the group into informants. Such was the extent of security force penetration of paramilitaries that in the early 1990s the PIRA killed more of its own members as suspected informers, than it did members of the British military. Sophisticated electronic surveillance measures and effective army and police framework operations also contributed to the increasing quality of security force intelligence and decreasing freedom of action for the PIRA.

The other reason for reduced effectiveness of the PIRA was the increased activity of the loyalist paramilitaries against both the Catholic community in general and the PIRA in particular. The loyalist paramilitaries were not aggressively targeted by the security forces for the simple reason that in a resource-constrained environment they were considered the lesser of two evils. The loyalist paramilitaries, as a matter of policy and general practice, did not target security forces. That said, there is also no doubt that many in the RUC and in the major army reserve unit, the Ulster Defense Regiment (UDR), were at least sympathetic to the loyalist paramilitaries if not actual members of one of the various loyalist organizations. Much of the arms and intelligence that the Protestant paramilitaries had available came from these sympathetic sources – hundreds of weapons were stolen over the years from UDR armories. Thus, the loyalist paramilitaries were a significant and capable force and in the late 1980s and 1990s they began to hit Catholic and suspected PIRA targets with great effectiveness. In 1992 the loyalist paramilitaries killed 38 people compared to the republicans killing 40, however in 1993 they killed 49 compared to 38 killings by the republicans, and in 1994 it was 37 to 25. In many ways these statistics are indicative of even greater violence, since the population that the loyalists targeted was significantly smaller than the PIRA’s target population.

Though the loyalist paramilitaries were not officially sanctioned by the British government, they operated outside of the law, and they often – like the PIRA – targeted innocent civilians, there is no denying that they were very effective in influencing events. The Catholic civilian population feared the loyalist paramilitaries because of their ruthlessness and because there was no protection against them. The PIRA also feared them because, unlike the security forces, they were not inhibited by any notions of due process and rule of law, and they were willing to attack the friends and relatives of the PIRA when the primary targets were not available. Both groups also feared the loyalists because they were very effective. The PIRA and the various loyalist paramilitaries frequently engaged in cycles of tit-for-tat violence that affected both sides. However, because of the loyalists’ larger numbers and sympathizers within the security forces, the PIRA most often came out the worse from the exchange. These conditions made the Catholic community more sympathetic to a peace process which might halt the sectarian attacks, and it encouraged the Sinn Fein politicians within the PIRA to push the organization to accept a political solution given that the military strategy of bombings and sniping was becoming problematic.

Because of the increased military pressure from security forces and loyalist paramilitaries, and the decreasing support from the Catholic community in general, the PIRA declared its first extended cease-fire in August 1994. During that time it negotiated with the British government but, because of the dependence of the Conservative British government on Protestant votes in Northern Ireland, the negotiations made little progress. The major issue was the requirement to decommission PIRA weapons prior to substantive talks regarding a political settlement, a requirement to which the PIRA and Sinn Fein would not agree. In February 1996, the PIRA’s cease-fire ended. In May 1997 the Conservative British government of John Major was replaced by the Labour government of Tony Blair. The Blair government continued the process begun by Major, but since it did not rely on Northern Irish votes, it compromised on the issue of decommissioning, permitting that issue to be discussed in parallel with political talks. In July 1997, the PIRA renewed its cease-fire. On April 10, 1998 – Good Friday – the governments of the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain, along with the representatives of most of the prominent political parties of Northern Ireland, agreed to a political solution to the sectarian Troubles of Northern Ireland. Sinn Fein represented the PIRA in the negotiations and signed the agreement. The only major party that did not agree was the loyalist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Among the important provisions of the agreement were: respect by all parties for human rights; respect for the desires of the majority regarding the issue of unification; understanding of the interest of the Republic of Ireland; rejection of violence as a means of settling political disagreements; and finally that both unification with Ireland and independent membership in the United Kingdom were legitimate political positions.

The Good Friday Agreement effectively ended the conflict in Northern Ireland, though much political negotiation, and police and military operations, remained. Republican opposition to the agreement continued to manifest itself through violence carried out by a splinter group of the PIRA – the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA). They made their opposition known most violently in the Omagh car bombing in August 1998 which killed 21 people of all affiliations and wounded over 100. However, groups like the RIRA and their loyalist equivalents did not have large followings and had decreasing political effects after 1998. Managing the efforts of such groups was well within the capabilities of the RUC (renamed the Police Service of Northern Ireland [PSNI] in 2001) without army support. After 1998, violence like the Omagh bombing and smaller-scale events tended to reinforce public support for the power-sharing formula that the Good Friday agreement put in place. The last British soldier killed in the Troubles died in Northern Ireland in 1997. The last member of the RUC killed as part of the Troubles died in 1998. In July 2007 the British Army formally ended Operation Banner, the British military operation in Northern Ireland, after 38 years.

Over the course of the 38-year war with the Irish paramilitaries in Northern Ireland the role of British conventional forces was substantial and important. The bulk of the army forces deployed to Northern Ireland were required to perform two different but related missions depending on the circumstances during their deployment. One mission was population control during marches and riots. The other was what came to be called framework operations. Framework operations were routine operations conducted regularly to keep continuous pressure on the paramilitaries and ensure that the security forces retained the tactical and operational initiative. There were three main types of tactical framework operations: patrolling, vehicle checkpoints, and observation posts.

Patrols were used to show the presence of the security forces, add protection to RUC patrols, discourage the movement of paramilitaries, and obtain both knowledge of local conditions at the tactical level, and intelligence. In the early years patrols routinely detained individuals for formal questioning but this was eventually found to alienate the civilian community and was replaced by patrol members – not necessarily the patrol leader – “chatting up” people encountered during the patrol. Patrols were vulnerable to both explosives and gun attacks. The key to the protection of the patrols was keeping the timing, area, and routes random and unpredictable. Also important was mutual protection. The typical attack occurred by a gunman who ambushed a patrol at short range and then made a quick escape. Single patrols were very vulnerable to this type of attack. Gun attacks were most easily discouraged by threatening the escape of the gunman. To do this the British Army first developed the technique of mutually supporting parallel patrols. An attack on one patrol quickly brought the other patrol in support. This idea was enhanced by eventually developing the multiple-patrol technique in which several small teams, typically three or four consisting of four men each, patrolled in a seemingly random pattern, frequently crossing tracks, but always within supporting distance. Explosives could not predict where or when the patrol would be and gunmen could not predict where the supporting patrols were located and thus could not be assured of an open escape route. The key to the success of patrolling was carefully planning the patrol routes. The paramilitaries were very careful to study patrol routes and if they discovered patterns in the activity they planned operations accordingly.

Vehicle checkpoints were another way to reassure the public and to limit the mobility of the paramilitaries. Checkpoints fell into two types: permanent, and unannounced temporary checkpoints, called “snap” checkpoints. The permanent checkpoints were necessary to ensure security-force control of major roadways, however they were vulnerable targets themselves and rarely disrupted paramilitary operations because of their overt nature. However, their role was denial of access to the major routes and forcing paramilitary movement onto the smaller and slower secondary road network. The army established snap checkpoints to ensure that the paramilitaries understood there were no safe movement routes and they occasionally did result in the identification and arrest of known paramilitaries.

Observation posts fell into two broad categories: covert and overt. Overt observation posts served the same purpose as permanent vehicle checkpoints: they denied freedom of movement to the paramilitaries in particularly important areas. Covert observation was much more difficult. Throughout the campaign, regular army units employed close observation platoons that operated covertly to observe and gather intelligence. They received specialized training and would typically occupy derelict buildings at night and remain hidden in position for days. Overt observation posts were heavily protected positions in important, heavily trafficked parts of cities or in neighborhoods known to be sympathetic to paramilitaries. They used a wide range of sophisticated listening and observation devices and again, the expectation was that these known positions would deny the use of the area to the paramilitaries.

Intelligence analysis and acquisition was probably the most important element in the success of the security forces at all levels of operations. By the end of the campaign one in eight British troops in Northern Ireland was directly involved in the intelligence process in some manner. In addition to the techniques contributed by the regular army infantry units and the special operations units mentioned above, as time went on the army developed a significant electronics intelligence capability which included cameras, signals intelligence, and airborne intelligence – both manned and unmanned. In addition the army intelligence capability was integrated into the local intelligence network run by the RUC Special Branch. This capability was relatively ineffective in the early years of the war, but by the 1980s it was a very sophisticated and effective operation. Also MI5, a British national intelligence agency, had a strong presence in Northern Ireland. However there were problems throughout the history of the conflict, with the various intelligence agencies not effectively sharing information. Still, in the last decade of the campaign the combined intelligence capability of the security forces severely constrained the paramilitaries and disrupted literally hundreds of operations before they could be executed.

There are many strategic lessons that can be taken from the British experience fighting a determined and skilled insurgent in the urban areas of Northern Ireland. One of the most important, learned only over time by the British forces, was that the key to success was the allegiance of the civil population. In the case of Northern Ireland, the key factor was the attitudes of the Catholic and Protestant communities. The various paramilitaries were in a similar situation – needing to be perceived as legitimate by the civilian population. The strength of the PIRA came from its support in the Catholic community. That support was generated by the aggressive actions of the RUC and the sectarian policies of the Stormont government in the early years. That support hardened in the face of the relatively clumsy and unfocused army counterinsurgency efforts through the 1970s. Arguably, it took the entire decade of the 1980s and the first years of the 1990s for the British security forces to learn to apply more sophisticated tactics, tied into an integrated political and military strategy, and wean the Catholic community from its steadfast support of the PIRA.

One of the keys to the ultimate success of the British strategy in Northern Ireland was the army learning the counterintuitive effects of military actions. What the British security forces learned, over many years, was that when the PIRA indiscriminately attacked civilian targets, support for it among the general Catholic population decreased. However, as the security forces responded to the PIRA attack with searches, arrests, and raids, often poorly targeted and involving collateral damage to innocent civilians and their property, support for the PIRA increased. These phenomena perpetuated the cycle of violence in the war and in fact became part of the PIRA’s long-war strategy. However, in the mid-1980s, the security forces began to discern that if the security forces responded to PIRA violence covertly, or with precisely targeted arrests, there was a net decrease in popular support for the PIRA. Thus, as the security forces took a lower profile in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the popular support for the PIRA slowly and steadily decreased. The PIRA’s response to decreasing support was to lash out with even less discriminating attacks and thereby further delegitimize itself in the eyes of the Catholic population. Losing the confidence and support of the general Catholic population was not the only reason that the PIRA was at increasing variance with Sinn Fein’s political strategy, but it was an important aspect in why the PIRA ultimately conceded to a political solution to the war.

The British Army’s experience in Northern Ireland is an important demonstration of the increasingly sophisticated nature of urban warfare in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Importantly, the British Army’s operations in the Northern Ireland conflict required a much more complex understanding of the role of military forces and the definition of success and winning in war than was required to understand most previous conflicts. Northern Ireland demonstrated that winning an urban insurgency was as much about an integrated national counterinsurgency strategy as it was about military effectiveness. The British military was never seriously challenged directly by the military capabilities of the paramilitaries. However, effective paramilitary politics, information operations, combined with ineffectual British government political reforms and an abysmal economic environment, allowed the PIRA and other paramilitaries to be effective out of all proportion to their actual military capabilities. The British Army won its war with the paramilitaries in the urban environment of Northern Ireland not because it destroyed the paramilitaries, but rather because it created a secure enough environment such that political reform and compromise, and economic development could advance to the point that the information operations of the paramilitaries were ineffective. Thus, urban warfare had evolved to the point that it was not about destroying the enemy, instead military operations were about creating secure enough conditions that political success was possible.