After many years absent from major urban combat, the Russian army, the victors at Stalingrad and the largest, most lethal urban battlefields of World War II, found itself once again confronting urban combat, this time in the Russian province of Chechnya. In the early 1990s, separatist movements sprang up all over the former Soviet empire as people, long subjugated by Moscow, sought to take advantage of the end of the Cold War and win sovereignty for themselves. The traditional inhabitants of Russia’s Chechen province were one of the ethnic groups who wanted self-determination, and in 1991 they declared their intent to become independent and took control of the province, and its capital city Grozny. It wasn’t until 1994 that Russia tried to reassert its claim to dominion over Chechnya, and the Russian army invaded.

In the early 1990s Chechnya had a total population of about 1.2 million. The province is located in the north Caucus Mountains region of southern Russia. It is bordered on the west, north and east by the Russian Republic. In the south it shares a border with the country of Georgia. The terrain of the province is generally mountainous and covered with dense forests. The city of Grozny, in the center of the country, was the focus of most military operations during two separate wars between Chechen independence forces and the Russian army, in 1994 and 1999.

Grozny was a city that traced its roots to the early 19th century when Russia, at war with the Ottoman Turks, formally claimed the area. Terek Cossacks of the Russian army established a fort called Fortress Groznaya (which means “Terrible” Fortress). Grozny was an important outpost from which Czarist Russia, through its Cossacks, controlled the Muslim mountain people indigenous to the northern Caucasus. Before World War I, oil was discovered in Grozny and the surrounding area and economic development transformed the military base into a city. During the Russian Revolution and the civil war which followed, the Cossacks, then the basis of the Russian ethnic population in Grozny, sided with the pro-Czarist White forces and lost control of Grozny to the Bolsheviks who were aided by the indigenous Muslim tribes. Over the next 70 years Grozny was the center of much anticommunist sentiment – stemming from both the anticommunist Cossacks and the Muslim mountain people. Both the Cossacks and the Muslims were subjected to forced migration by the Communists. Their places in Grozny were taken by non-Cossack Russians. By the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, most of the Muslim population had returned and they made up about two-thirds of the population of the province, but only a small percentage of the urban population of Grozny, which remained largely ethnic Russian. Russians claim that prior to the first Chechnya war in 1994, most ethnic Russians were forced by the Chechen majority to flee Chechnya, thus in the first battle of Grozny most of the city’s residents were Muslim. However, some international observers and the advocates of an independent Chechnya claim that the Russian population was never forced to leave by the Chechen government, and remained until forced to depart by the war conditions, when Russian bombing caused between 200,000 and 300,000 ethnic Russians to flee the province. In 1994, in the months before the first battle for Grozny, the city had a mixed Chechen-Russian population of approximately 490,000 – almost a third of the province’s population. The city and its suburbs covered approximately 90 square miles. The city was a mixture of buildings ranging from one-story residences to massive 15-story housing structures. Almost all of the structures in the city were made of reinforced concrete. The Sunzha River was a major terrain feature within the city and flowed northeast to southwest dividing the city into a northern and southern sector.

On December 11, 1994, the Russian Republic, under President Boris Yeltsin, launched its military into Chechnya to restore that province to the control of the Republic. The Russians were motivated by a number of factors, the two most important being access to, and control of oil; and ensuring that they stopped the dissolution of the former Soviet Union while the Russian Republic still had sufficient land and resources to be regarded as an international power. Chechnya had significant indigenous oil stocks, and its location, and particularly the location of the city of Grozny, made it a key distribution point for oil and oil products coming from neighboring provinces. By 1994 Chechnya had effectively been independent for almost three years – though its status was not legal according to the Russian constitution, and it was not recognized by the Russian government in Moscow. Other peripheral provinces were in danger of following the Chechen example. Thus the government in Moscow determined to demonstrate that it had the will and capability to preserve the integrity of what remained of the former Soviet Union, lest further disintegration occur. By December 21, Russian forces had advanced through Chechnya and closed in on Grozny from the north, southwest, and east. On December 26, the Russian government authorized the Russian army to advance into Grozny itself.

The Russian army that served the Russian Republic in 1994 appeared to be virtually identical to the formidable Soviet Red Army which had intimidated Europe for half a century and which had destroyed the vaunted German war machine in World War II. However, less than five short years after the end of the Cold War, the army was neither the mighty machine that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II, nor the menace that had threatened NATO since the 1950s.

The battle for Stalingrad during World War II had honed the Soviet army into an expert urban warfare force. Subsequent campaigns in World War II built on that expertise, which reached its peak in the battle for Berlin in 1945. However, after World War II, Soviet forces gradually lost that expertise. The Soviet army was not committed to any significant large-scale combat for almost 50 years – the one exception being Afghanistan where no major urban combat occurred. More importantly, Soviet doctrinal thinkers focused on operational maneuver warfare. The Soviet army believed that the major lesson learned in World War II was that victory was the result of flexible and rapid maneuver by massed mobile armies built around large armor and mechanized infantry formations. The prospect of lengthy and resource-consuming urban combat was anathema to the maneuver focus of the Red Army. Soviet army leaders believed that in a confrontation with NATO, western armies would abandon western European cities rather than see them and their populations destroyed in street-by-street battles. They also believed that any city that might be decisively defended could be bypassed by mechanized spearheads, and then carefully reduced or induced to surrender once surrounded. Urban warfare, once a key competency of the Red Army, was absent from both Soviet doctrine and practice by the end of the Cold War.

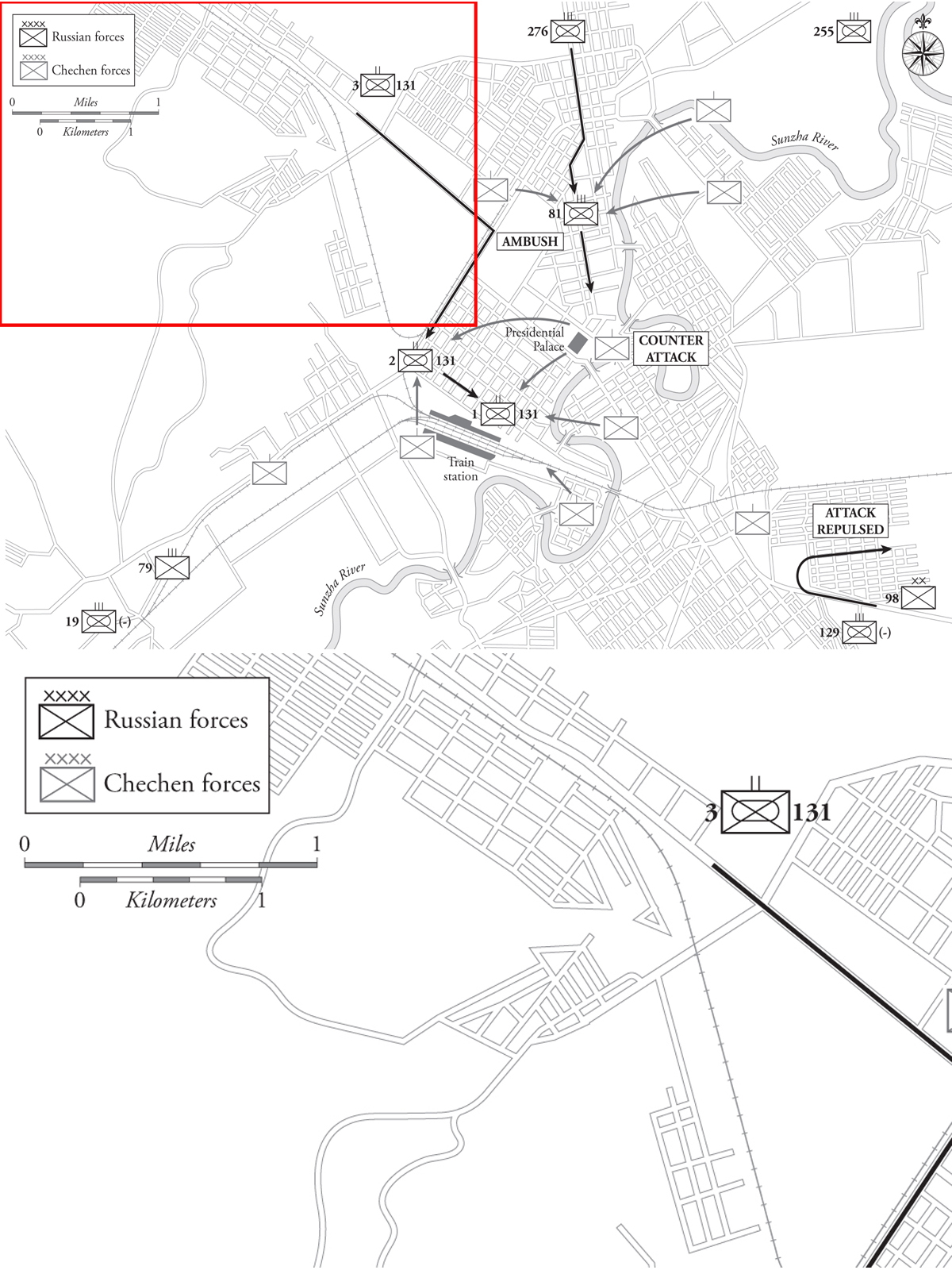

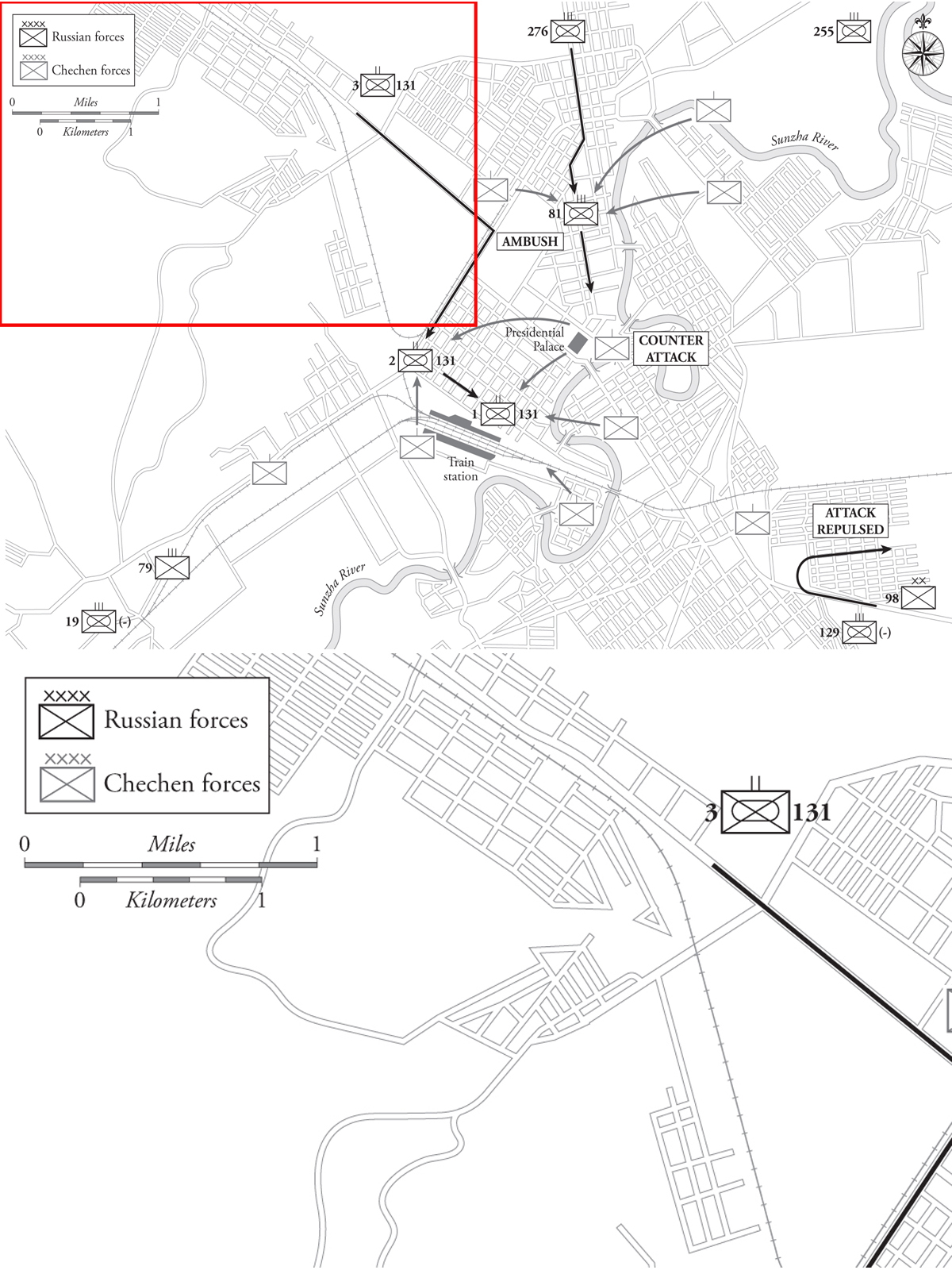

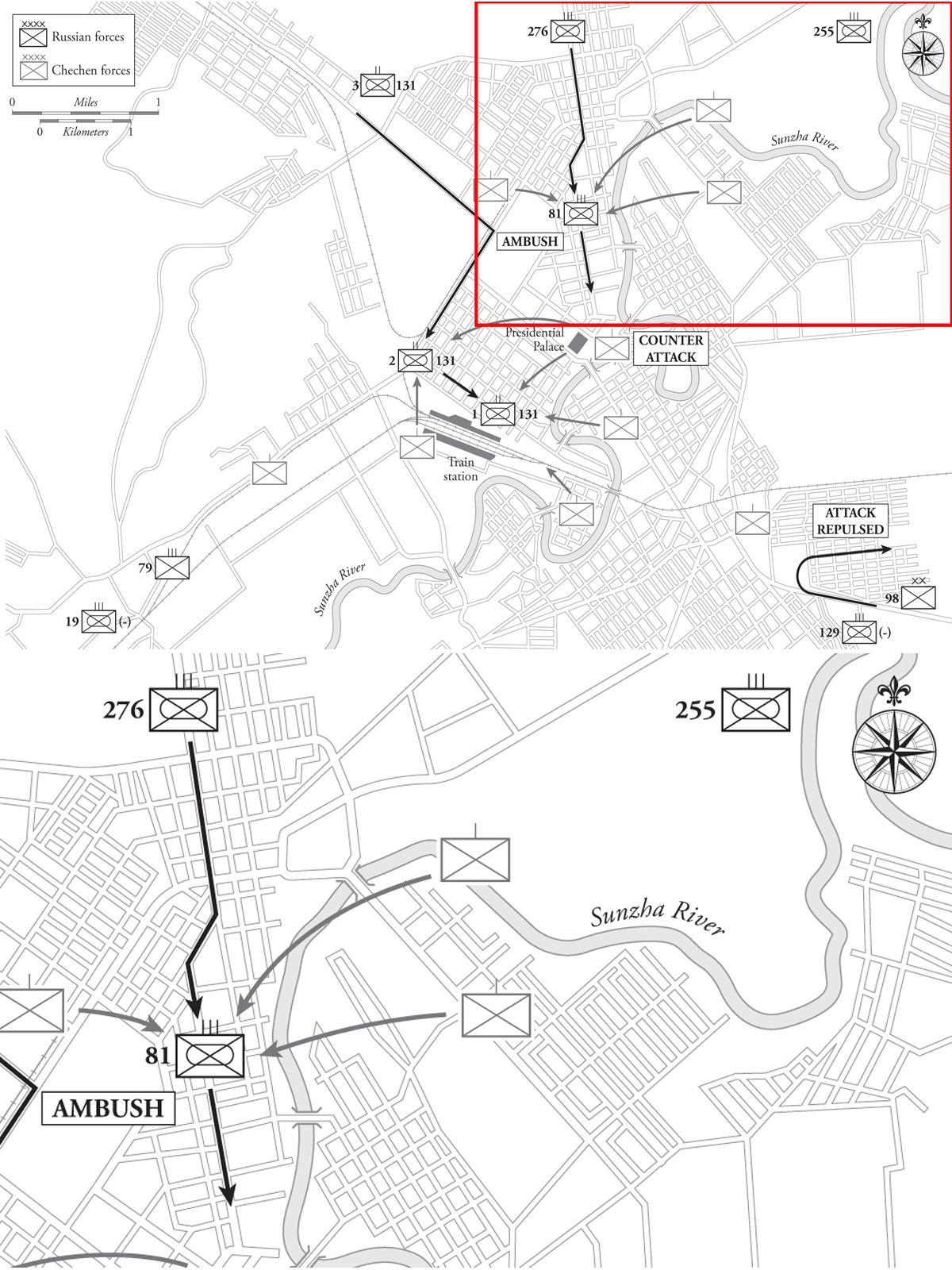

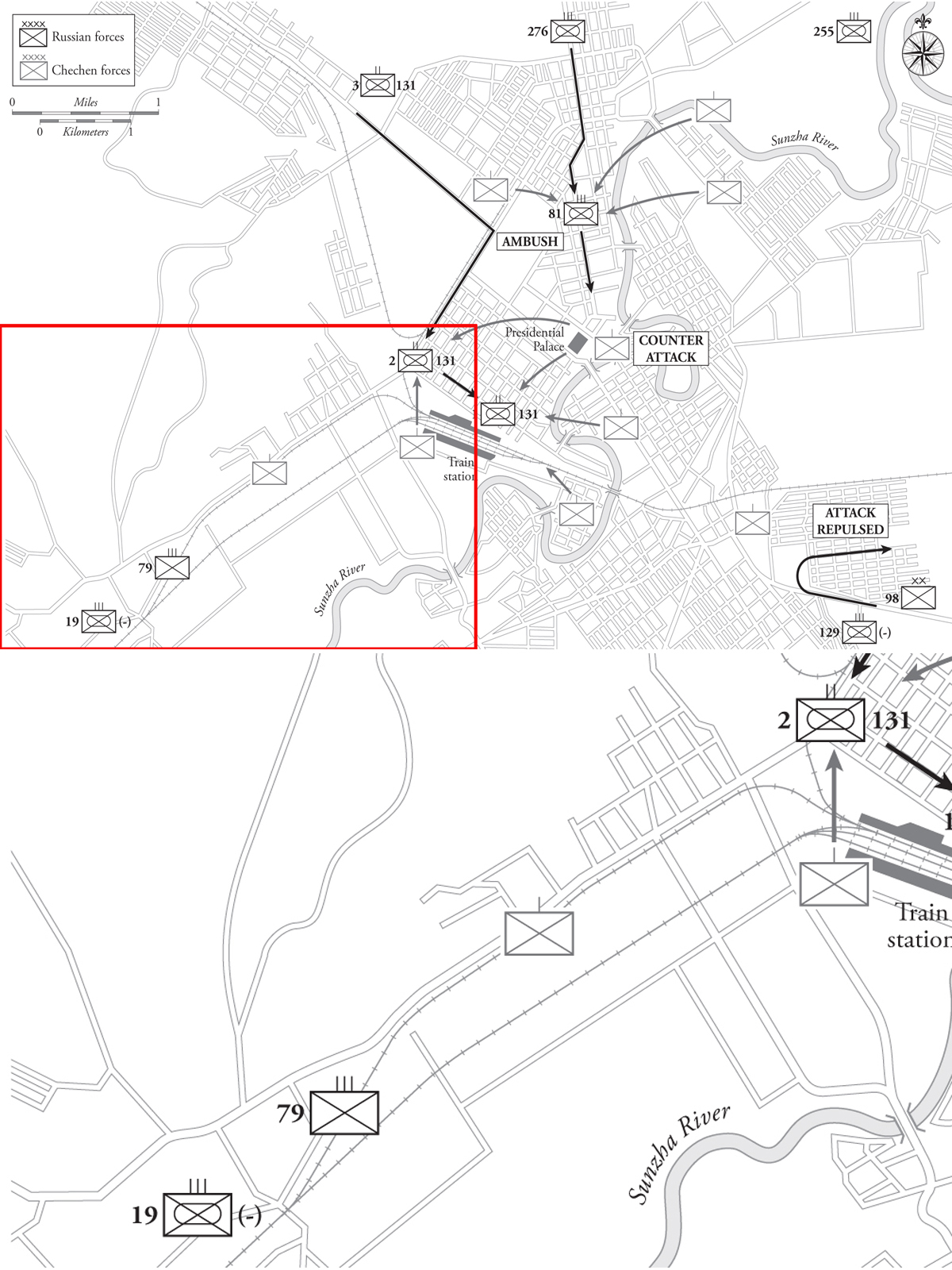

Map 8.1 The Initial Russian Attack into Grozny, December 1994

The Red Army of the Cold War, despite its lack of expertise in urban fighting, was still a superbly equipped, well-led, and well-trained modern military force. However, the same could not be said for the army that entered Chechnya just four years after the end of the Cold War. The political collapse of the Soviet Union heralded an internal collapse inside the Red Army. Communism, and the discipline and authority built around the Soviet Communist Party, was one of the bedrocks of the Red Army. When Soviet Communism collapsed so did the Red Army. Externally, the army still appeared a formidable force. Though Soviet military forces had numbered over five million in the late 1980s, the rump of the forces still available to the Russian Republic in 1994 retained a formidable strength of over two million. However, the quality of the force was dubious.

The collapse of the Soviet Union was occasioned by the collapse of the Soviet economy. The economic collapse had significant effects on the army. Budgets were cut and training was cancelled; and more importantly, routine logistics functions came to a standstill. The army could barely feed itself, and getting access to necessary commodities such as fuel became problematic. As the country disintegrated politically, the population began to refuse to comply with conscription. As regions of the country declared their autonomy from Moscow, large elements of the military stationed in those regions, such as the Ukraine, broke away. The military high command was focused more on political survival and privileges than on its soldiers and units. Soldiers in garrisons began to desert. Other soldiers sold their personal, and even unit equipment, including weapons, in order to buy food and alcohol. Pay for the soldiers, never very much, failed to materialize for months. Regular army units, the motorized rifle regiments and divisions, were the hardest hit by these conditions. Elite units such as paratroopers and Spetsnaz special operations forces, nuclear forces, and the air force and navy were not as dramatically affected. The conditions within the regular army forces were disastrous. By 1994 most units were only shadows of their paper personnel strengths, they were receiving virtually no training, and much of their equipment was inoperable.

The Russian force assembled outside of Grozny in December 1994 numbered nearly 24,000 men: 19,000 from the Russian army and approximately 5,000 from Russia’s internal security forces. The army forces consisted of five motorized rifle, two tank, and seven airborne battalions plus supporting artillery, engineers, aviation and other elements. The major army equipment included 80 tanks, over 200 infantry fighting vehicles, and over 180 artillery pieces. There were over 90 helicopters in the supporting aviation element. Despite these numbers, the force’s combat power was modest by Cold War standards. Its combat elements resembled the combat power of a reinforced motorized rifle division. The seven airborne battalions were some of Russia’s best elite troops, however the airborne battalions themselves were very small units and the total of the seven battalions was likely smaller than that of the five motorized rifle battalions. The concept of the Russian operation was for the army to lead the advance to Grozny. Then, on order, attack the city to seize important government, economic, and communications centers. The internal security units would advance behind the army and once the city was under army control the security forces would take over control from the army.

Chechnya, the breakaway province, did not have an army. The military forces of the province were built around a small cadre of former Soviet soldiers. They formed a small provincial guard that probably numbered fewer than a thousand. Another group of approximately 5,000 was made up of irregular volunteers with little formal military training. They were led by those volunteers who had experience in the Soviet army, of which there was no shortage. There was some Russian military equipment left in the province following the withdrawal of the Soviet Army in 1991, which included about 40 main battle tanks, 30 armored personal carriers and scout vehicles, and about 30 122mm medium artillery pieces. The Chechen fighters organized as squads of six to seven men. Each squad had at least one RPK medium machine gun, one RPG rocket-propelled grenade launcher, and one designated sniper. Three squads combined with a medium (82mm) mortar team made up the basic fighting unit. Three of these platoon equivalents were formed to make up a 75-man fighting group, the equivalent of a small company. They communicated with each other using commercial handheld radios. The Chechen forces’ major advantage other well, and had a thorough knowledge of the urban terrain over which they fought.

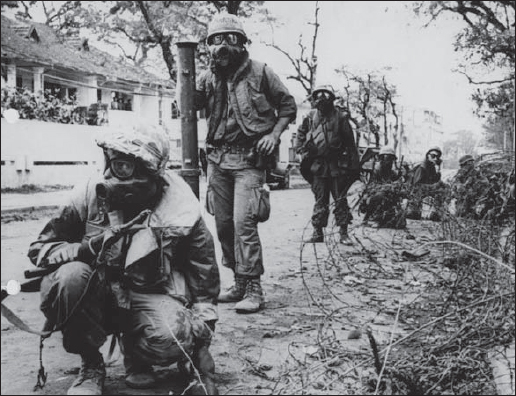

Marines wearing protective masks prepare to employ CS gas and assault a building to clear out snipers. The use of CS gas as part of military operations has since been outlawed by international agreement, though it is still used widely for riot-control purposes. (Getty)

Marine infantry of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, fight their way from house to house in the old city north of the Perfume River. The lead Marine on the left in this photo is armed with the M-60 light machine gun and carries a smoke grenade. The other Marines are armed with M-16 assault rifles and carry extra ammunition for the machine gun. (Topfoto)

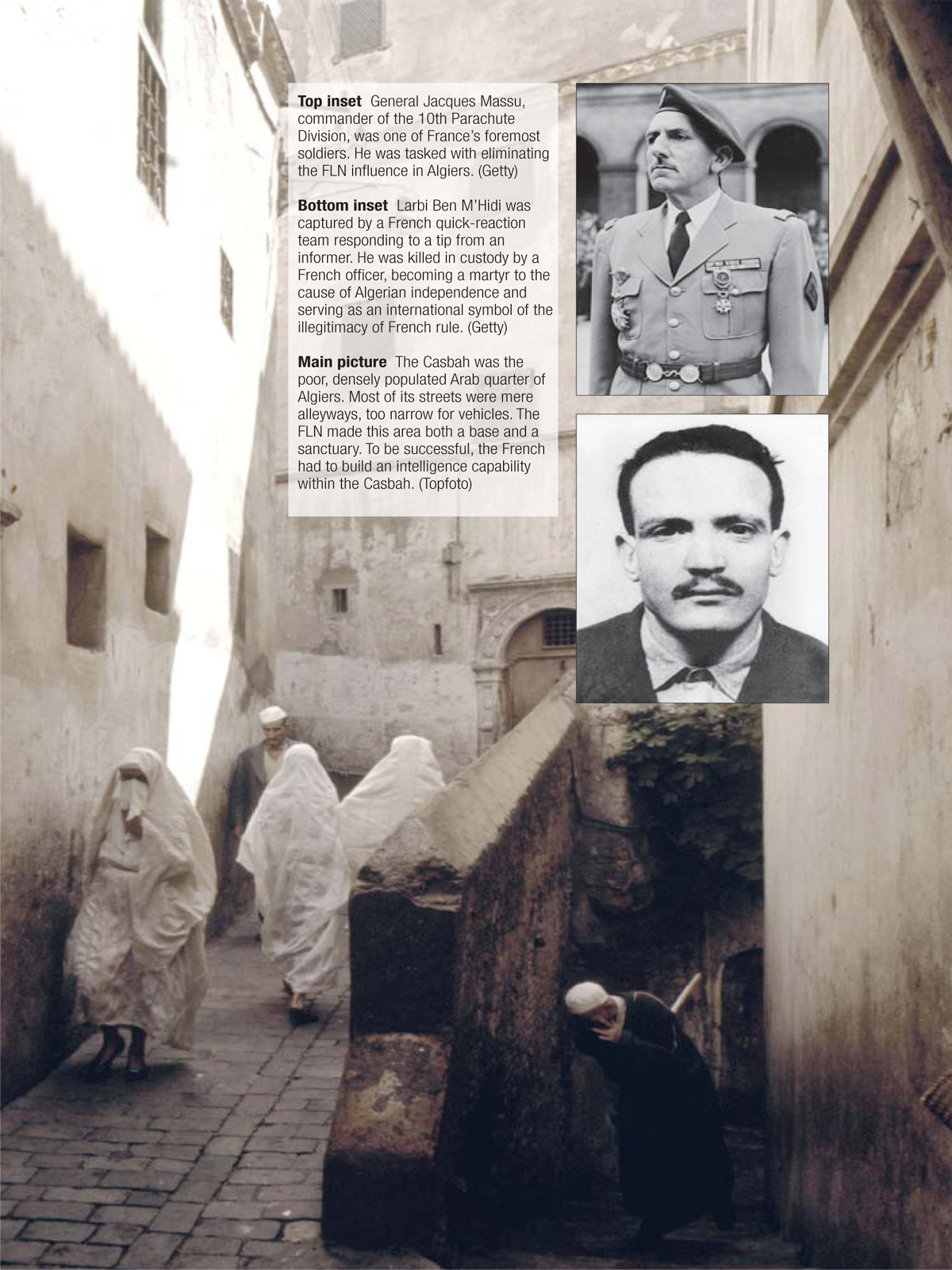

French paras enter Algiers. The French paratroopers were the elite of the French army and, with extensive experience in Vietnam, considered experts in revolutionary warfare. (Getty)

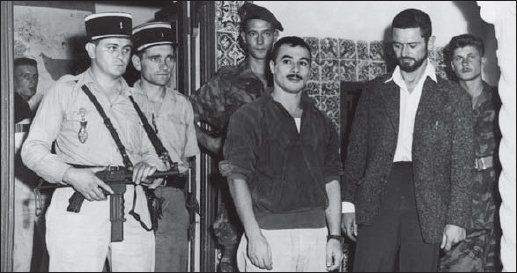

Yacef (center) was the leader of the FLN’s military arm in Algiers. He established an extensive network of bomb-makers, bombers, and supporters throughout the Casbah. This network was systematically destroyed by the French through the use of very controversial interrogation techniques, including torture. (Getty)

Soldier of the 3rd Battalion, The Light Infantry, passes ruined terraced housing during a patrol of one of the Peace Lines in Belfast in 1977. Poverty and lack of opportunity were legitimate grievances of the Catholic community and led to the beginning of the war. These grievances could only be answered with political action. (IWM, MH30550)

Soldiers from 2nd Battalion, Royal Anglian Regiment, fire baton rounds at rioters during “hunger strike riots” in Bogside, Londonderry, 1981. (IWM, HU41939)

An officer of the 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, and lance corporal of the 2nd Battalion, The Queen’s Regiment, patrol a Belfast street with a Saracen wheeled armored personnel carrier (APC). Both Saracen APCs and Ferret armored cars were used for many years in Northern Ireland because of the protection they provided their occupants. Because they were wheeled vehicles their use was less controversial than a deployment of tracked armored vehicles would have been. (IWM, TR32986)

A Company, 1st Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment, moves up to the Diamond, Londonderry, to control a riot between Protestant and Catholic women in 1970. (IWM, HU43396)

British troops guard a barricade in the early months of the conflict. When first deployed to Northern Ireland the British Army was seen as a neutral arbitrator in the conflict, but events quickly forced the army to support the sectarian government of Northern Ireland. (Topfoto)

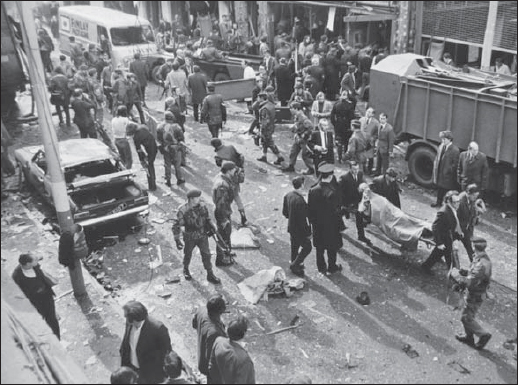

The results of a deadly PIRA bombing in Belfast on March 20, 1972: seven were killed and over 150 injured. This was the most violent year of the entire campaign with a total of 479 people losing their lives. Bombing was the tactic of choice of the PIRA. It was a pure terror weapon that most often resulted in random civilian casualties. (Fred Hoare)

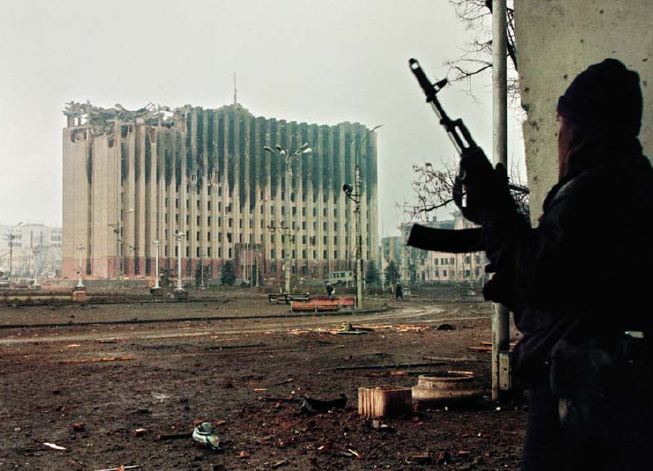

Russian soldier in Grozny. The Soviet troops, although superbly equipped, were mostly poorly trained conscripts – in their initial exposure to urban combat they performed miserably. The buildings in this photo demonstrate that the Russians’ response to tactical challenges was often massive artillery bombardment which ultimately destroyed much of the city. (Topfoto)

Chechen fighter outside the Presidential Palace. This was the primary objective of the New Year’s Eve Russian assault. The command of the Chechen resistance was in a bunker in the basement of this building and remained active until overrun by Russian troops. (Getty)

A destroyed Russian BMP2 armored personnel carrier in Grozny. These vehicles, armed with a very effective 30mm cannon and carrying a squad of infantry in the rear, had the potential to be very effective in urban combat. However, poor command and control combined with hastily assembled and undertrained units resulted in the Russian debacle on New Year’s Eve, 1994. (Getty)

Chechen fighters on the streets. Organized into groups of about 25 men, armed with a variety of Russian weapons and cast-off Russian uniforms, led by experienced former Russian army leaders, and fighting in their own city, the Chechen mobile combat groups were formidable foes. (Getty)

Israeli infantrymen, armed with the M-4 carbine variant of the M-16 assault rifle, move carefully from house to house in Jenin. (IDF)

Merkava tanks move through Jenin as part of Operation Defensive Shield. The Israeli military employed large numbers of armored vehicles as part of the operation largely because the armored protection reduced friendly casualties. (IDF)

The Israeli military made use of a variety of types of infantry in the urban operations in the West Bank depending on the difficulty of the mission. The different types included reservists, regular mechanized infantry, paratroopers, and special operations forces. (IDF)

Israeli infantry enter a building in Jenin using a sledgehammer. The IDF operations in the West Bank were security operations in a hostile country rather than classic counterinsurgency. There was no friendly civilian population and no attempt to win “hearts and minds.” (IDF)

A Merkava tank observes Jenin. Another role of armor was to isolate the urban areas and control traffic in and out. Stationary outposts built around tanks were designed to prevent the escape of fighters from the urban objectives. (IDF)

1BCT Commander Colonel Sean MacFarland and his security detail enter Ramadi hospital, the largest and most modern building in the city, in July 2006. It would be several weeks before US Marines established sufficient presence in the area and were able to declare the hospital under US control. (Defence Mil)

Aerial view showing the Euphrates River as it runs north of Ramadi. The river was an important and imposing terrain feature. Controlling the river using riverine forces was an important aspect of 1BCT’s plan to secure the city.

Infantrymen of Team B, Task Force 1st Battalion, 35th Armored Regiment, provide security from a street corner during a foot patrol in the Ramadi suburb of Tameen. Both soldiers are armed with M249 5.56mm light machine gun. (US Military)

US Marines in urban combat in Iraq. This picture illustrates some of the equipment employed routinely in urban combat in Iraq including googles (day and night), protective knee pads, M-240 machine guns, M-16 assault rifles, body armor, and a variety of weapons optics including night scopes and flashlights. (USMC)

An M-1A1 Abrams tank suppressing insurgents during a firefight. The protection and firepower of the tank was an integral part of the operations of the 1BCT as it secured Ramadi. The pyschological effect of tanks and tank-fire on the enemy was as important as the material benefits the tank contributed to operations. (USMC)

A USMC infantryman in Ramadi. The infantry, as in all urban operations, was the centerpiece of operations in Ramadi. In Ramadi the infantry, US Army and Marine alike, practiced the “three block war”: intense fighting on one block, assisting police and guarding infrastructure on another block, and providing humanitarian relief and economic assistance on a third block. (USMC)

The Libyan rebel army occupies the capital city of Tripoli in January 2012. One of the challenges of hybrid urban warfare is distinguishing friendly fighters from enemy fighters as both sides may wear the same uniform, or no uniform, and will likely be using the same or similar equipment. (Getty)

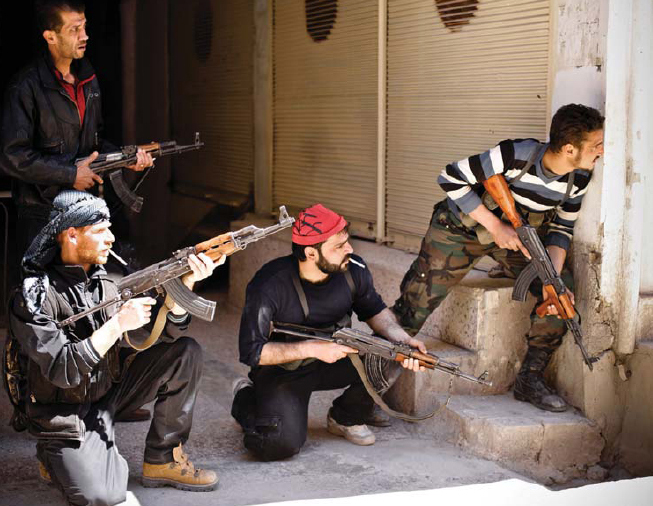

Syrian rebels fighting government forces in Aleppo, April 2012. The face of future urban warfare will not be that different from urban warfare of the past. The combatants will likely be indistinguishable from combatants seen in Iraq, Ireland, Algeria, or Hue, may be armed with similar small arms and RPGs, and will probably practice similar tactics. (Getty)

By December 30, 1994, the Russian forces completely surrounded the city of Grozny. Though positioned on most of the major routes into the city, the Russians did not orient their force to isolate the city. For most of the battle the Chechen forces were able to bring supplies and reinforcements into the city from the southeast.

Four assault task forces were formed to attack into the city along four separate axes. From the southwest, General Major Petruk would attack with a regiment from 76th Airborne Division and two mechanized assault groups from the 19th Motorized Rifle Regiment. Their objective was the city railroad station, and to isolate the Presidential Palace from the south. A task force under General Major Pulikovsky was assigned to attack from the northwest with the 131st Motorized Rifle Brigade, and elements of the 276th and 81st motorized rifle regiments. The 255th Motorized Rifle Regiment under General Rokhlin was given the mission to attack the city from the northeast. Finally, General Staskov was to lead the southeastern task force consisting of elements of the 129th Motorized Rifle Regiment and part of the 98th Airborne Division. Their mission was to occupy the southeastern part of the city and seize a series of bridges over the Sunzha River. On paper this appeared to be a very formidable force and a solid plan, but only because it did not reflect the problems inherent throughout the Russian military in 1994. None of the units had trained in large-scale military operations, much less urban warfare. The motorized rifle units in particular were made up of hastily assembled units from all over Russia and many soldiers had only been together for a few weeks. Collective training as a unit was almost nonexistent and the individual training of many soldiers barely covered the use of their individual small arms. Commanders were not given time to conduct detailed planning for their missions, undertake reconnaissance, or rehearse with their troops.

The Russians were not expecting to fight a sustained battle for the city of Grozny, nor were they mentally or physically prepared for such a battle. Thus, as the battle developed, initial failings on the Russian side were as much due to lack of understanding of the situation as to professional incompetence, although there was an abundance of the latter. There were three phases of the battle. Phase one was the opening days of the attack. During this phase Russian commanders and soldiers were not fully aware of the combat environment in which they were engaged. In phase two of the battle, the Russian forces reorganized, developed tactics, and systematically wrestled the northern portion of the city from the Chechen defenders. In the final phase of the battle, Russian forces secured the city, eliminated the remaining Chechen forces in the northern part of the city, and pushed the Chechen forces out of southern Grozny.

The plan for the entry into the city was reasonably well conceived. However, its execution was extremely poor. Of the four major commands that were to enter the city, only one mounted a determined effort. In the west, the predominantly airborne forces of General Major Petruk encountered light resistance in the industrial areas just outside the city. However, the planned air support for the attack did not appear, and the units stopped their advance to await developments. In the east the airborne task force under General Major Staskov met heavier resistance on its assigned route of advance. The Russian forces, rather than fight through the resistance, turned north seeking an alternate route. They then ran into minefields and barricades. This force too, stopped its attack and awaited further orders. The northeastern force, under General Rokhlin, moved into the outskirts of the city and then considered its mission accomplished and switched to the defensive. The only force that made a determined effort to achieve its assigned objectives was the mechanized task force under General Major Pulikovsky approaching from the northeast – and they paid a great price for it.

General Pulikovsky’s force began its movement at 6am on December 31. Though ostensibly attacking to seize the city, the command’s understanding of the situation was completely unrealistic. Pulikovsky and his subordinates viewed the operation as a show of force to intimidate the Chechens into submitting to Moscow’s governance. They did not expect any serious opposition and therefore the units moved forward in a column formation with no reconnaissance or security forces deployed. Some of the motorized infantry slept in the back of their armored carriers. By midday, Pulikovsky’s force had entered the outskirts of the city. The 81st Motorized Rifle Regiment proceeded down Pervomayskaya Street moving directly south toward the Presidential Palace, while the 131st Motorized Rifle Brigade moved parallel to them to the west along Staropromyslovskoye Boulevard and then Mayakovskaya Street. Initially all went well and the tanks and armored personnel carriers rumbled slowly down the very quiet streets of the city in carefully organized and aligned columns – as if on parade. The movement was very slow and deliberate, partly because the Russians were in no hurry, and partly because the units were not well trained and commanders wanted to ensure they did not lose control.

In the early afternoon, the 81st MRR made contact with the Chechen defenders. Numerous Chechen battle groups, probably totaling more than a thousand fighters, ambushed the carefully spaced column of armored vehicles from buildings and alleys on both sides of the street. Squads of fighters engaged with the armored vehicles with machine guns and RPGs from the upper stories of buildings. The top armor of the tanks and armored vehicles was thin: the RPGs easily penetrated the armor and destroyed numerous vehicles. The leaders of the Chechen forces were veterans of the Soviet army and knew how to execute an ambush. The attacks focused first on the lead and trail vehicles in each march unit. Once they were destroyed, the other vehicles were trapped and exposed in the street, which quickly became congested. Then, at a more leisurely pace, the RPG fire systematically engaged the rest of the column. Russian officers tried to rally their men but the buildings made radio communications difficult and the individual Russian units were hastily put together, consisted of many new conscripts, and very poorly trained. They were not equipped to operate on their own and when isolated by the ambush and lack of communications, discipline quickly broke down. Russian troops abandoned their vehicles and fought their way to the rear. Many didn’t make it to the hastily organized rally points. The Russians found that the ZSU-23-4 mobile antiaircraft vehicle, which was armed with four rapid-firing 23mm cannon, was one of the few weapons that could quickly and effectively suppress Chechen ambush positions. The rapid fire of the heavy cannon easily penetrated building walls, and the ability of the turret to traverse rapidly and elevate the guns to rooftops intimidated snipers and RPG gunners. The performance of the ZSUs was a small Russian success in an otherwise dismal battle performance. The crews of tanks and BMP mechanized fighting vehicles jumped from their vehicles, often while they were still operational, and made their way by foot to the rear. Other vehicles did not move, waiting in vain for orders, their engines idling until they were hit and set ablaze by Chechen RPGs. By afternoon the attack of the 81st MRR was completely defeated and the regiment was chased from the streets of Grozny, leaving behind dozens of abandoned and destroyed tanks and personnel carriers.

In contrast to the advance of the 81st MRR, the 131st Rifle Brigade’s move into the city was unopposed. By 3pm the brigade had reached its initial objective and reported no opposition. It was ordered on to its final objective in the center of town: the main railway station and town square. The brigade was unaware of the fate of the 81st MMR. By late afternoon the brigade reported its arrival at the railway station without opposition. One battalion occupied the station; a second battalion occupied the freight station several blocks away. The third battalion remained in reserve on the outskirts of the city. The troops at the main station dismounted and many went into the station and generally took a break. No effort was made to establish a defensive position. The brigade assumed the other attacking units were having similar experiences and would soon be linking with them at the station.

Not long after arriving at the station, the 300 men of the 1st Battalion, 131st Brigade were engaged by Chechen small-arms fire. After destroying the 81st MRR, Chechen fighters roamed the city looking for additional Russian units to attack, and discovered the unprepared battalions of the 131st. The Chechen fighting groups communicated by radio and soon fighters from all over the city swarmed toward the railway station. Suddenly BMP infantry fighting vehicles and tanks in the city square were exploding from RPG hits. Many of the Russian troops were dismounted and not near their vehicles. Troops who were in the vehicles were caught unaware, had no idea what was happening or where the enemy was, and because of their poor training, were unable to respond effectively. The Russian soldiers found themselves surrounded and under attack from rockets and machine guns from all sides. Estimates are that over a thousand Chechen fighters surrounded the station. Officers who moved into the open to evaluate the situation and rally their men were quickly cut down. Due to poor communications, and poor coordination, radio calls for reinforcements and artillery support went unanswered. The troops at the railway station formed a perimeter in and around the railway station and waited for reinforcements.

The fight at the railway station quickly engulfed the battalion at the freight station and it too saw its stationary vehicles destroyed by rockets fired by quick-moving gunners popping out of alleys or firing from the upper stories and roofs of buildings. Machine-gun fire and snipers kept the battalion pinned down, and destroyed vehicles blocked many of the streets. As in the 81st MRR ambush, tank crews found that their main guns could not depress low enough to engage enemy in the basements of buildings, or elevate high enough to engage the upper stories and roofs of buildings. In some cases crews panicked, and were gunned down as they abandoned tanks and armored personnel vehicles that were still operational. The reserve battalion was ordered to move in and reinforce the engaged elements of the brigade, but they were ambushed on the same streets that had been clear and quiet that morning and were quickly pinned down and fighting for their own survival. As darkness fell, the battle at the railway station raged on.

The morning of January 1 began with groups of Russians, including the bulk of the 131st Brigade, pinned down in the city or on the routes leading into it. Russian operations focused on extracting their forces and suppressing the Chechen fighters. Weather grounded the Russian air force on January 1 and 2, but the Russians relied heavily on the one weapon that the Chechens and the weather had little ability to affect: artillery. Russian artillery began pounding the city on January 1, in what appeared to be an indiscriminate manner. In reality, the Russians were attempting to hit what they thought were Chechen defensive positions, not realizing that what they perceived as a deliberate Chechen defense of the city built around strong defensive points was in reality moving ambushes. Thus, Russian artillery ravaged blocks of apartments as well as obvious military targets such as the Presidential Palace. The main victims of the barrages were Chechen civilians. Russian units remained trapped in the city, most notably the battalions of the 131st Brigade, hunkered down in defensive positions under constant Chechen sniping. Units outside the city, in particular parachute infantry units that had not been prepared to attack the previous day, attempted to renew the attack but the Chechen fighters, buoyed by their success the previous day, stymied all Soviet attempts to resume the attack. The Russian units outside the city were still unclear of the situation inside the city and the position of the surrounded units. Some Spetsnaz Russian special forces and paratroopers penetrated into the city but had no real objective. They wandered the city trying to avoid being cut-off themselves and eventually fought their way back to their own lines.

On January 2, the remnants of the 131st, mounted in previously abandoned armored vehicles recovered from the battlefield, attempted to break out of the city. The brigade commander was killed as the survivors fought through Chechen ambushes to escape the city. By January 3, what remained of the brigade had either escaped the city, died, or been captured. The brigade had lost the entire 1st Battalion – approximately 300 men and 40 armored vehicles. In total the brigade lost 102 of 120 armored vehicles, and 20 of 26 tanks; almost all of the officers in the brigade had been killed; total casualties in the brigade were approximately 700–800 personnel. The 81st MRR lost approximately 60 armored vehicles and suffered several hundred casualties. In total the two brigades that attacked from the north lost over 200 armored vehicles of all types, and sustained approximately 1,500 casualties. The Chechen fighters tried to take advantage of their success and push the Russian forces completely out of Grozny on January 2 and 3, however the Russian forces were very formidable in defense and the Chechens suffered significant casualties without removing the Russians from the city approaches. The failed Chechen counterattacks ended the first and bloodiest phase of the battle for the city.

After the defeat of the New Year’s Eve attack, the Russian army reorganized, reevaluated, and prepared to renew the offensive. The second phase of the assault to capture Grozny began on January 7, 1995. This time the Russians executed a systematic attack in which infantry platoons supported by tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, armored personnel carriers, artillery and mortar fire, and air strikes, systematically advanced through the city toward the Presidential Palace. The small Russian assault groups attacked each building, captured it, and used it as a base to assault the next position. Artillery fire advanced ahead of the infantry. Tank fire raked each building before the infantry attacked. In this manner the Russians advanced steadily, block by block, toward their objective. They also systematically destroyed the city as they moved, and undoubtedly killed countless civilians caught up in their advance.

As the Russians attempted to advance on January 7 they met renewed Chechen resistance. The Chechens used a variety of techniques to thwart the rapid Russian advance. Civilians were taken hostage, Chechen fighters blended in with the civil population wearing civilian clothing, buildings and derelict vehicles were booby-trapped, sewers and other subterranean tunnels were used to move unobserved behind advancing Russian forces, and minefields and barricades were used to channel Russian forces into prepared ambush sites. The Russians responded by increasing the use of artillery and dispatching small reconnaissance units. The reconnaissance units were also tasked with finding pockets of Russian survivors from the New Year’s Eve attack and Russian soldiers being held prisoner in the city. Despite firing artillery into the city at a rate of 20–30 rounds a minute, the Russians were unable to make significant advances. Reports indicated that even Russian special operations units were captured by the Chechens. On January 9 the Russians paused and unilaterally declared a cease-fire to begin the next day and last until January 12. Both sides violated the cease-fire but no major offensive operations occurred.

On January 12, Russian forces resumed the attack, beginning with a three-hour artillery and rocket barrage aimed at the city center. Intense fighting occurred as reinforced Russian units fought building to building toward the city center aiming to capture their original objectives including the railway station and the Presidential Palace. Elite Russian naval infantry units were added to the mixture of Spetsnaz, paratroopers, motorized infantry, and tank units fighting into the city. Additional Russian troops moved south of the city to attempt to close routes that were being used to both resupply and reinforce the Chechen forces in the city, and evacuate key leaders and heavy equipment out of the city. For five days Russian forces systematically fought toward the city center. On January 19 the Russians secured the Presidential Palace and two days later the train station and the center of the city. The Russians then moved to the north bank of the Sunzha River and mopped up remaining pockets of Chechen fighters. On January 26, Russian military units turned over control of Grozny north of the river to internal security police forces. Chechen resistance in the center of the city had collapsed, but the battle was not over. The Chechen combat groups, estimated by the Russians to number about 3,500 fighters, withdrew over the Sunzha River, blowing up bridges as they withdrew, and established a new defense on the south side of the river.

While police security forces, reinforced by the army, battled isolated pockets of Chechen fighters left on the north bank of the river, Russian military forces crossed the river to drive the fighters from their remaining strongpoints in the final phase of the battle. The Russians made liberal use of air support, attack helicopters, artillery, and Shmel flamethrowers. The Shmel weapons were particularly effective at clearing snipers and RPG gunners from suspected ambush positions. The Chechens were fighting a rearguard action not so much to protect withdrawing forces but rather to draw out the battle. Every day of resistance and fighting in Grozny was a political and propaganda victory for the Chechens. On February 8, the Russians declared 80 percent of the city under their control. On February 16, a four-day cease-fire was called to exchange prisoners and wounded. On February 20, combat resumed and three days later the Russians surrounded the last significant Chechen forces in the city ending major operations.

The battle for Grozny was an intense six-week urban combat experience. Total Russian losses during the battle are estimated to be approximately 1,700 killed, hundreds captured, and probably several thousand wounded. Chechen casualties are completely unknown due to the inability to distinguish fighters from civilians and the decentralized and informal structure of the Chechen forces. Most of what is known of the battle is the result of researchers putting together snippets from contemporary news reports, official Russian reports, and interviews with participants on both sides. Both the Chechen and Russian leadership had, and continue to have, a vested political interest in portraying the performance of their forces in the best possible manner and denying operational difficulties. On the Chechen side the defense of the city has to be considered a victory despite the loss of the city. The outnumbered and underequipped defenders of the city prevented a larger, lavishly equipped force from securing the city for almost fifty days. Simultaneously, they inflicted significant tactical losses on the attackers, waged an effective information campaign, and greatly strengthened the political strength and legitimacy of the Chechen independence movement. The best that can be said for the performance of the Russian forces is that they eventually achieved their objective. The battle revealed a surprisingly low level of capability within the military forces of Russia.

The actual operational details of the battle are sparse, but a great deal is known about the tactical techniques applied by both sides. On the defense, the Chechens fought what some have called a defenseless defense. They relied on the unusual urban tactic of mobile combat groups rather than strongpoints. This tactic was particularly effective in the early stages of fighting because the Russians attacked to penetrate the city along specific axes of advance rather than on a broad front. The Russian approach, lack of adequate command and control, as well as insufficient numbers and disregard for their flanks, allowed the Chechen mobile groups to maneuver throughout the city at will and control the initiative in the battle even though they were on the defensive. As the Russian force grew in size and the Russian attack became more systematic in the second and third phases of the battle, it became more difficult for the Chechen forces to maneuver.

A Russian response to the Chechen tactic was the development of “baiting.” Small forces, such as a mechanized platoon or squad were sent forward to spring a Chechen ambush. Once exposed, a larger mobile force, supported by attack helicopters and artillery, used massed firepower to overwhelm the Chechen fighters. The Chechen response to the deliberate and expansive use of artillery and airpower by the Russians was “hugging.” Once engaged, Chechen fighters moved as close as possible to the attacking Russians to make it impossible for the Russians to employ their massive advantages in artillery and airpower. The Russian goal in the streets of Grozny was to identify the Chechen defenders before becoming decisively engaged and then destroy them with long-range direct and indirect firepower. The Chechen approach was just the opposite: stay as closely engaged with the Russians as possible. The employment of these tactics resulted in massive amounts of damage and significant civilian casualties as neither side considered collateral damage an important tactical consideration.

The most effective tactical weapons employed in Grozny were a mixture of old and new technology. The sniper armed with his scoped rifle proved a very reliable and essential element of successful urban combat. The Chechen forces employed formally trained snipers as well as competent designated marksmen in the sniper role. The Russian army, once they reverted to systematic offensive operations, included snipers to cover the infantry as they assaulted buildings. A new weapon, employed by both sides but with particular effect by the Chechen forces, was the rocket-propelled grenade, the RPG-7. This weapon was incredibly easy to use and lethal to all armored vehicles, including tanks. It was lightweight and easily carried by one man and so could quickly be positioned in the upper stories of buildings and on rooftops. The Chechens demonstrated the versatility of the weapon as they used it against armored vehicles, in open areas against infantry, against low-flying helicopters, and even in an indirect fire mode by launching the rockets over the tops of buildings at Russian forces on the other side. The Russians had access to this weapon as well but limited its use primarily to the traditional anti-armor role. Chechens sometimes increased the lethality of their snipers by equipping them with an RPG as well.

Russian forces employed a new weapon, one that had not been seen in urban combat before but which was ideally suited to the environment: the RPO-A Sheml. The Sheml was called a “flamethrower” by Russian sources but in its operation bore little resemblance to the traditional flamethrower that literally projected burning fuel at the target from short range. The Sheml was a rocket-propelled thermobaric weapon. It launched a 90mm rocket from a lightweight launch tube at targets up to a thousand meters away. When it hit the target the warhead of the rocket dispersed a fuel igniter which exploded after mixing with oxygen from the surrounding air. The resulting explosion was extremely powerful and hot. Enclosed areas such as bunkers, caves, and buildings magnified the effect of the explosion. Typically, any flammable materials in the vicinity were ignited. The Sheml became a favorite weapon for dealing with suspected sniper and RPG positions. The devastating effects of the weapon had a psychological impact on Chechen fighters, who rapidly abandoned firing positions before the Russians could launch a Sheml in response.

Tanks were a critical component of the Russian army’s success, as proven in other conventional urban combat experiences. However, the use of tanks evolved over the course of the month-long battle. At the beginning, Russian attacking forces relied extensively on tanks as the basis of operations: tanks led the attack and were supported by the other arms. Using these tactics Russian tank losses were extensive. The high losses among the tank forces caused the Russians to change their tactics by leading with dismounted motorized rifle troops and paratroopers. Dismounted forces were followed closely by infantry fighting vehicles and antiaircraft systems such as the ZSU 23-4. Tanks overwatched operations and added the weight of their main guns to the fight but were careful to always remain behind a screen of infantry.

From the very beginning of the battle, the Russians made frequent and liberal use of artillery. Artillery was a traditional weapon of the Russian army in battle but in Grozny it had only limited positive effects. The availability of supporting artillery in large numbers did much to reassure Russian troops of their firepower superiority over the Chechen forces. This was an important psychological effect given the shock to Russian morale caused by the New Year’s Eve attack. However, Russian artillery was not particularly effective against the Chechen forces because of the fluid nature of their defensive tactics. The lavish use of artillery, however, had a large adverse effect on the civilian population and on Russian civilian support for the war. Most of the residents of the central part of the city were ethnic Russians and they became the victims of Russian air and artillery bombardment. Estimates of civilian casualties in the six-week battle range from 27,000 to 35,000 killed. The number of wounded civilians was estimated to be close to 100,000. The Russian and international media reported negatively on the civilian loss of life and support for the Russian war effort suffered both within Russia and in the international community.

The battle for Grozny demonstrated the importance and effects of information operations on urban combat in the digital communications age. The Russian government tried to prevent information leaving the battlefield rather than managing that information. Reporters were barred from moving with Russian troops and observing the battlefield freely from the Russian side. In contrast, the Chechen commanders encouraged the media to observe their operations and interview commanders and soldiers. The Chechens, using the media effectively, managed to portray the battle as sympathetic freedom fighters fighting against the oppressive army of a tyrannical regime. Despite the efforts of the Russian government, information reached the Russian population anyway, but that information often dramatically contradicted official Russian government statements and was sympathetic to the Chechen point of view. The Russian government quickly lost credibility with both the Russian people and the international community. Political opposition to Russian military operations consequently grew rapidly, both within and outside Russia.

The Russian military successfully seized the city of Grozny from the Chechen fighters in 1995. However, the methods they employed indicated the major characteristics of the Russian military. First, it was a blunt military instrument and incapable of precise operations. The Russian military did not outfight the Chechens, it overwhelmed them. Second, Grozny demonstrated that the Russian government did not understand the careful coordination between the instruments of national power necessary for success in urban operations in a digitally connected and global political environment. Russian disregard for information operations, collateral damage, and particularly civilian casualties gave the Chechens significant strategic advantages even as they lost the battle at the tactical level. Those advantages would build over time, and result in Chechen forces recapturing Grozny in the summer of 1996, and in the negotiated withdrawal of Russian forces from Chechnya that same year. A formal treaty between the Chechen government and the Russian government was signed in 1997 which stabilized the relationship between the two governments until the war began anew in 1999.