In September 2000 the Palestinian people, represented by Yasser Arafat, his Fatah Party, and the Palestinian Authority (PA), began a low-intensity war against the state of Israel over a spectrum of grievances ranging from the original founding of Israel in 1948, to the failure of the Palestinian–Israeli peace talks brokered by US President Bill Clinton. That war was known as the Second Intifada, or the Al Aqsa Intifada. The Arabic word Intifada is translated as “uprising,” and from 2000 to 2005 it manifested as strikes, protests, and a clandestine war of rocket and terror attacks against Israel by various Palestinian groups. The Intifada ended in 2005 when a series of events including the death of Yasser Arafat dramatically decreased the terrorist attacks from within the territory controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

The violence waged against Israel increased to unprecedented levels in 2002 and early 2003. Attacks were occurring inside Israel at a rate of one every three to four days. In March 2003 the violence reached a new level: nine attacks occurred between March 2 and 5. These were followed by suicide bomber attacks on March 9, 20, and 21, as well as numerous gun and grenade attacks. The attacks culminated with the suicide bomb attack on the Park Hotel in Netanya on March 27, which left 30 dead and 130 injured. March became one of the bloodiest months of the Intifada as 130 Israelis died in terrorist attacks. The Israeli government, under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, responded by ordering the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) to take action to prevent further attacks. The response from the IDF was Operation Defensive Shield.

Operation Defensive Shield was a large Israeli offensive military operation designed to significantly degrade the ability of a variety of Palestinian groups to attack Israel. The plan called for a massive movement of conventional Israeli military forces into the occupied West Bank territory to seize and destroy bomb factories and weapons caches, as well as kill or arrest Palestinian militant fighters, leaders, bomb-makers, and financiers. It was the largest military operation in the occupied West Bank area since Israel seized the territory from Jordan in 1967.

The concept of the operation was to rapidly, and in overwhelming force, occupy the Palestinian urban areas which were the bases from which various organizations staged terrorist operations into Israel. In phase one, the towns would be secured and access to the towns would become controlled. In phase two, the IDF would systematically raid known or suspected bomb-making facilities, and search residences suspected of harboring weapons or known members of terrorist groups. In the course of these operations the IDF planned to arrest and detain known or suspected members of a variety of terrorist groups. Specific raids were also planned to kill or arrest specific members of the terrorist leadership.

The Palestinian leadership did expect a response from the IDF, but they did not know exactly what form that response would take. The size and complexity of the operation came as a complete surprise to Yasser Arafat. The only Palestinian area that was prepared for the Israeli assault was the Palestinian refugee camp in Jenin. Under very able leaders, the Palestinian fighters in Jenin had some time to prepare a relatively sophisticated defense of the part of the city in which they were based. This was one of the reasons that Jenin became one of the centers of Palestinian resistance to the Israeli offensive.

The total population of the area called the West Bank was about three million residents including over half a million Israeli settlers. Most of the people lived in the major urban centers of the area. The population was predominately of Arab descent and Muslim (75 percent). The Arab Muslim population divided into two major groups: the original inhabitants of the region, and refugees who had come to the West Bank from Israel, mostly during and following the Israeli War of Independence in 1948. The refugee population numbered approximately 800,000 individuals, living in 19 camps. Two significant minority communities lived in the region: Christian enclaves which had been integrated into the communities of the region for centuries made up approximately 8 percent of the population; and Jewish settlers, who had moved into the region and established highly segregated communities after the Israeli conquest of the area in 1967, made up about 17 percent.

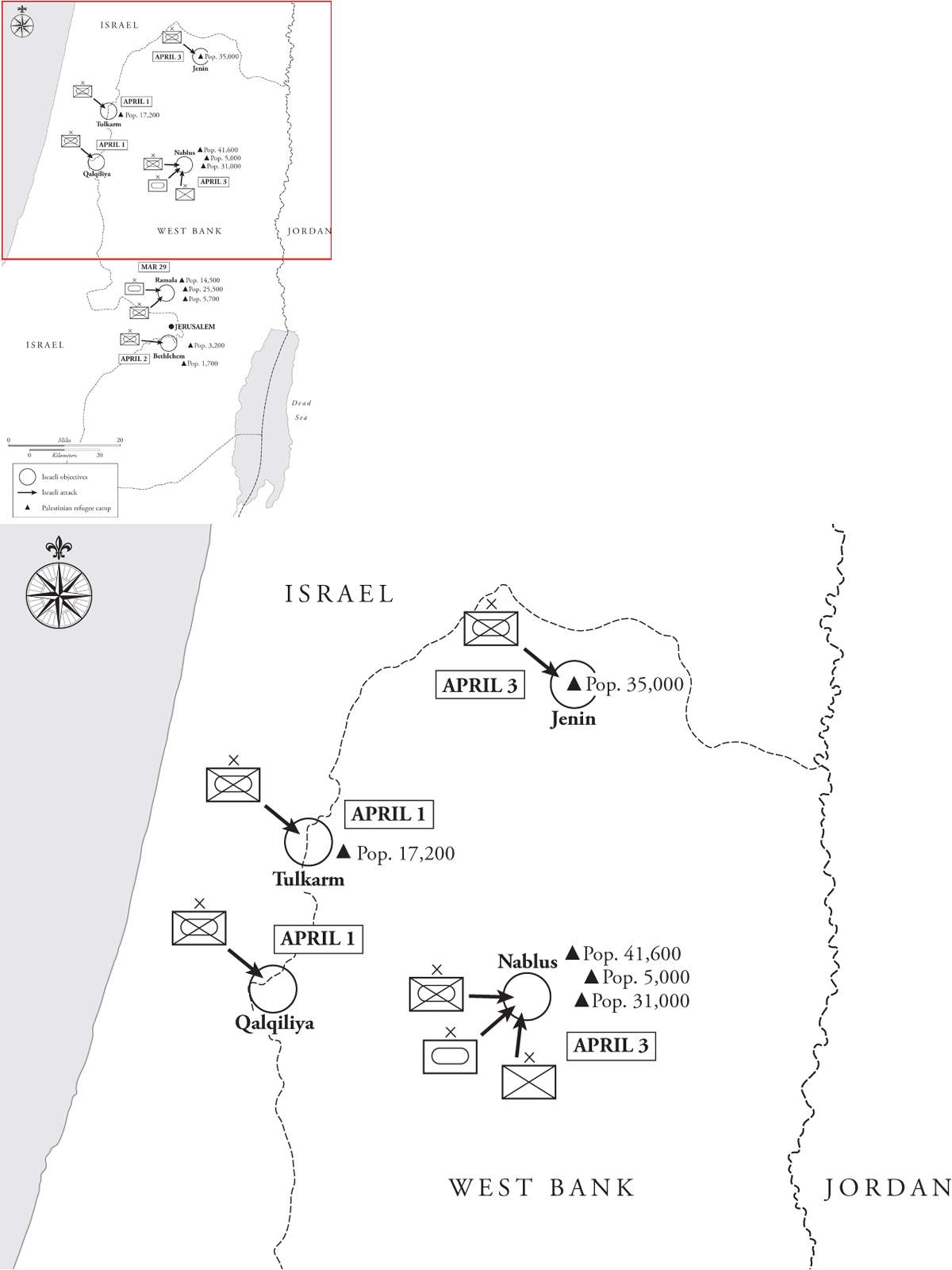

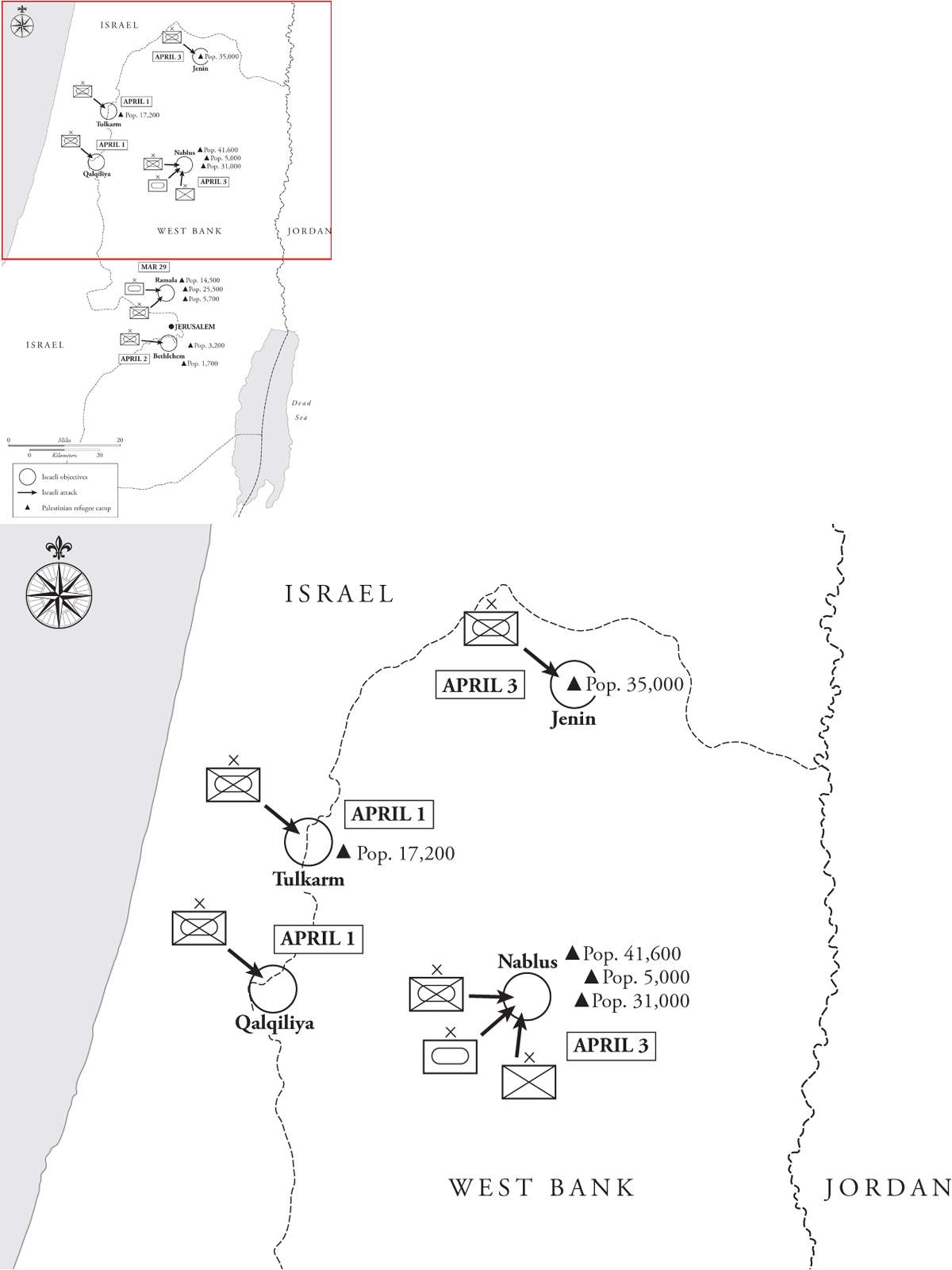

The six objectives of Operation Defensive Shield were the six most populous cities in the West Bank: Jenin, with a population of approximately 50,000; Tulkkarm, approximately 55,000; Qalqiliya, approximately 40,000; Nablus, approximately 125,000; Ramallah, approximately 25,000; and Bethlehem, with a population of approximately 25,000. In total about 325,000 civilians lived in the urban areas subject to Israeli operations. Though most of the population was sympathetic to the attacks on Israel, only a small portion was actively engaged in supporting terrorist activity.

Large Palestinian refugee camps were located adjacent or near five of the six urban areas targeted by the Israelis (the exception being Qalqiliya). The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) established the refugee camps in 1948, but they were camps in name only. More than 60 years after they were established, the camps resembled typical poor Middle Eastern neighborhoods. In many ways they were similar to the type of complex casbah building configuration that the French army had faced in Algiers. The buildings were low two- to three-storied flat-roofed buildings, made of concrete and brick, built around courtyards and narrow alleys. Most housed multiple families, and often a small group of buildings housed members of an extended family. The streets were typically wide enough for a small car, but many were pedestrian access only and just a few feet wide. The camps were integrated into the local communities economically, though they maintained a strong self-identity. The camps were largely self-administering, and had all of the amenities of the surrounding community including power and water. In some camps, such as the one in Jenin, local militant groups dominated the population, despite the presence of PA police and administrators. In total, approximately 180,000 refugees resided in the 10 camps associated with the cities targeted by the IDF.

The Israeli army was divided into an active force and a large reserve force. For Operation Defensive Shield, 30,000 reservists were called to active duty, allowing the IDF to mobilize several reserve brigades and division headquarters. The IDF ground forces were organized into three commands: Southern, Central, and Northern. The Central Command commanded Operation Defensive Shield while Southern Command monitored the Gaza Strip and the Northern Command remained focused on Syria. Each command had two to three active divisions, each commanded by a brigadier general; each active division had one to three brigades. The primary combat formation of the IDF ground forces was the brigade, which was assigned to a division but which, for operations, could be assigned to any division headquarters depending on the needs of the mission. IDF brigades were of three types: armor, mechanized infantry, and paratrooper. The brigades participating in Defensive Shield were either mechanized infantry, or paratrooper. Elements of the armored corps, as well as special forces, engineers, and air force attack helicopters, supported the infantry brigades. Each of the major objectives (cities) of the operation was assigned to an active division headquarters, and that division commanded the various brigades and supporting units attacking that particular city.

The IDF operations in the West Bank were aimed at disrupting three terrorist organizations, and by implication they also had to deal with a fourth organization that was armed and a potential adversary. The latter was the PA police forces. These forces were responsible for law and order in the West Bank, and were loyal to the PA led by Yasser Arafat. Thus, although they were not actively attacking Israel, they were expected to oppose the IDF incursion into the West Bank. There were three primary militant groups in the West Bank. The Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade specialized in suicide bombings as well as gun attacks. In 2002 they were covertly sponsored by the Fatah party, a relationship that was only admitted to after Operation Defensive Shield. The Palestinian Islamic Jihad was a small but deadly group that originated in Egypt and after several migrations was based out of Damascus, Syria. They had a close association with the Hezbollah terrorist group in Lebanon and through them with Iran. The last important active terrorist group opposing the Israelis in 2002 was Hamas. Hamas was the political rival of Fatah and had its strongest support in Gaza. However, like the other groups, it had a strong presence in the West Bank. Hamas was responsible for the very deadly Park Hotel attack just prior to the Israeli offensive. All three groups used the urban centers of the West Bank as bases for operations in and against Israel. They also used those bases to manufacture weapons, as recruiting and training stations, and to plan and conduct propaganda campaigns.

Map 9.1 Operation Defensive Shield, March–April 2002

Operation Defensive Shield began on March 29 as Israeli military forces launched into the West Bank to seize control of the city of Ramallah. The major objective in Ramallah was the headquarters of the PA and Fatah, and its leader Yasser Arafat. The IDF attacked Ramallah with a combined infantry and armor force supported by attack helicopters. IDF forces quickly penetrated into Arafat’s Tegart Fort compound and surrounded him in the offices of one building. By the end of the day the IDF had secured the city with no losses to the attacking forces. A curfew was imposed and the IDF then began to systematically seek and arrest known and suspected terrorists. Over 700 individual arrests were made. Thirty defending Palestinian militants and PA police were killed. Arafat remained in his headquarters, with all communications cut off, under house arrest, until May.

Two days after the seizure of Ramallah, April 1, the IDF seized the two border towns of Tulkarm and Qalqiliya. The IDF operations were not seriously resisted in either town. In Tulkarm nine militants were killed and the Tegart Fort used as the headquarters for the PA in the city was destroyed by an air strike. The next day IDF forces moved across the border into Bethlehem. That operation, thought to be relatively simple, turned into an international incident as the IDF surrounded and laid siege to 32 militants and over 200 hostages in the Christian Church of Saint Mary, thought to be the birthplace of Jesus Christ.

No substantial fighting units were thought to be in Bethlehem and the city itself borders on Israel proper, so staging and moving into the city were not considered major problems. For this reason, the mission was assigned to the IDF Reserve Jerusalemite Brigade, an IDF reserve unit. There was a high-value person list for Bethlehem whose arrests were a priority task of the operation. The IDF knew, from previous experience, that one course of action the militants could pursue, if given the opportunity, was flee to the Church of Saint Mary. This had happened on at least one previous occasion. For this reason the Jerusalemite Brigade was supported in its mission by the elite Air Force Shaldag commando unit (also known as Unit 5101). One of the commando’s missions was to secure the church to prevent its use as a sanctuary.

The operation was executed against sporadic and ineffective resistance and the town quickly came under IDF control. However, the Shaldag unit was delivered by Israeli Air Force helicopters to its positions a half hour late. That was sufficient time for armed militants to escape capture and find sanctuary in the Catholic church, and to take hostages. The church was quickly surrounded by IDF infantry and tanks and a 39-day siege began. Over the course of the next five weeks, the siege and IDF tactics and actions were subjected to the scrutiny of the international media and the subject of much diplomacy. During the siege, eight militants were shot and killed by IDF snipers stationed around the building. Two Israeli border police were wounded in one of the several small firelights that occurred. In the end, however, the siege was ended diplomatically with all the hostages released unharmed, and 39 militants going into exile in Sicily and Europe.

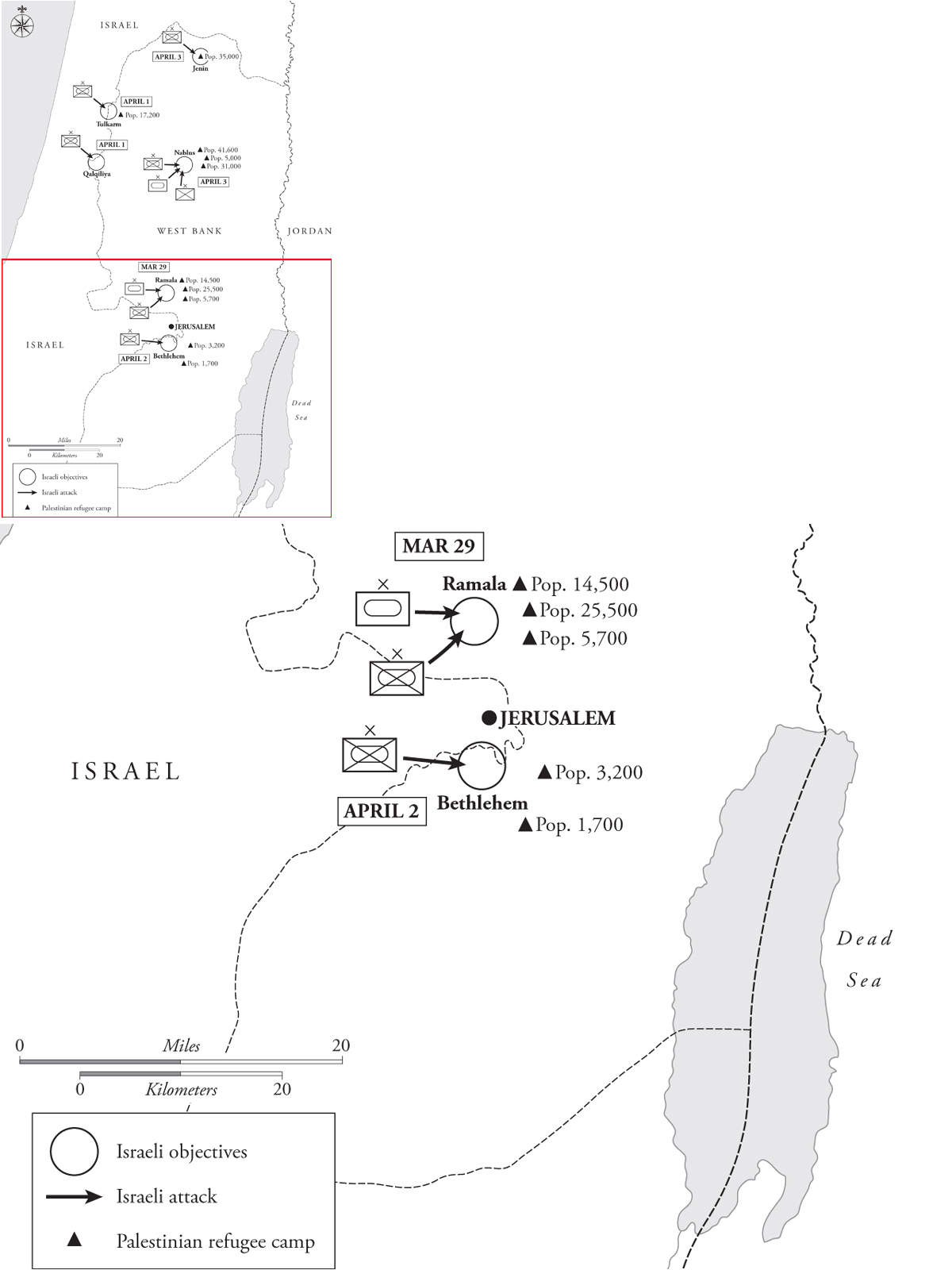

The major focus of Operation Defensive Shield was the two urban areas attacked on April 2 and 3, Nablus and Jenin. Nablus was considered the most difficult mission for several reasons: it was located deepest in the West Bank, it was the largest in total population, and it had the most refugee camps and the largest refugee population at over 70,000. Because of this the mission of seizing the city was assigned to the active army West Bank Division under Brigadier General Yitzhak Gershon. For the mission the division had two veteran Israeli brigades: the Northern Command’s Golani Infantry Brigade and the Paratrooper Brigade. The IDF activated a reserve armor brigade and assigned it to the division to provide support for the infantry.

Operations in Nablus began on April 3 and took about five days to complete. By April 8 the last militant fighters holding out in the old city casbah decided to surrender. The Israeli plan to capture the city was relatively simple. The Paratrooper brigade was responsible for clearing the Balata Refugee Camp, the largest in the West Bank with over 20,000 residents packed into a maze of buildings in .25km2. The brigade would then move west and enter the casbah, the old city quarter. The Golani Brigade moved through the city and attacked the old city quarter directly. Both brigades were extremely successful in accomplishing their mission of killing or capturing militants while at the same time minimizing civilian casualties, collateral damage, and most importantly, minimizing Israeli casualties, but they took dramatically different tactical approaches to achieving their aim.

The Golani Brigade, as mechanized infantry, took an equipment-centric approach to attacking Nablus. The general tactic was to work as an engineer, infantry, armor team. Tanks overwatched the tactics and suppressed enemy fire or potential enemy positions with machine-gun and tank fire. If the building being assaulted was occupied, the tank softened it up with fire from its main gun. The infantry assault was led by an engineer D9 bulldozer. The armored bulldozer was impervious to all Palestinian fire and it cleared the approach to the building of booby-traps, mines, and in many cases widened the alley or street so that it was large enough for the infantry carriers and tanks to follow. Once at the building, the D9 used its blade to collapse a wall and then withdrew. The dozer was followed by an Achzarit heavy armored personnel carrier. The carrier brought the infantry right to the building where they dismounted and attacked into the building through the breach created by the dozer. This method was a slow, firepower-intensive method that did a lot of damage to buildings but kept the advancing IDF force under armor protection most of the time. Special forces snipers also worked with the advancing mechanized force, picking off Palestinian fighters at long range as they attempted to flee, or maneuvered against the flanks of the advancing vehicles and infantry.

A different, but no less effective approach was used by the paratroopers. Though they had access to attached mechanized infantry, tanks and dozers, the paratroopers as a standard did not have the firepower or armored protection of the mechanized infantry so they could not use the same tactics. The paratroopers advanced using tried and true urban fighting techniques. As a tactical standard they refused to recognize and use windows and doors, and instead advanced primarily through the interior spaces of adjoining buildings. The paratrooper technique was to create mouse holes between buildings using explosives or pick axes, and move by squads along multiple planned routes, each route planned through a series of adjoining buildings. Stairs were also avoided and the troops moved between floors by blasting holes through floors and ceilings. The goal of the paratrooper advance was to reach their objective without ever appearing on the open street or alley. The paratroopers also employed their snipers to great effect. The snipers, firing from concealed positions and great distances, picked off targets as the advancing infantry forced the defending Palestinians to retreat or reposition.

As the Palestinian militants lost men and were gradually forced back they were equally frustrated by their losses and their inability to inflict any significant damage on the attacking IDF forces. Finally, in the face of dwindling resources, lack of success, and mounting casualties, the Palestinian groups in the casbah surrendered. The IDF suffered only one casualty in the battle and that was due to friendly fire. The Palestinian defenders lost approximately 70 fighters. Most surprising, given that intense combat in the midst of a large civilian population continued for five days, was the lack of significant collateral damage. Only eight civilians were killed in the fighting in Nablus, and despite employing bulldozers, tanks, and demolitions, only four buildings were completely destroyed, though hundreds were significantly damaged. The IDF took several hundred prisoners in the battle and killed or arrested numerous top-level experienced militant leaders.

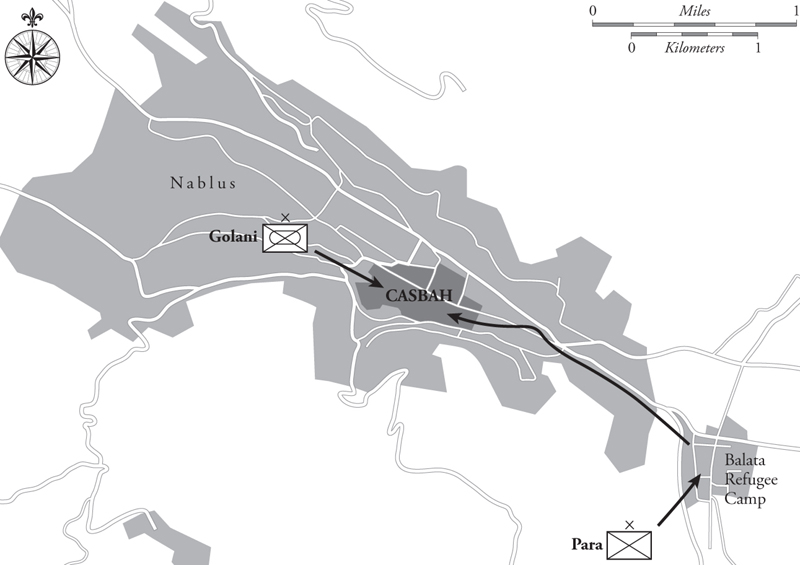

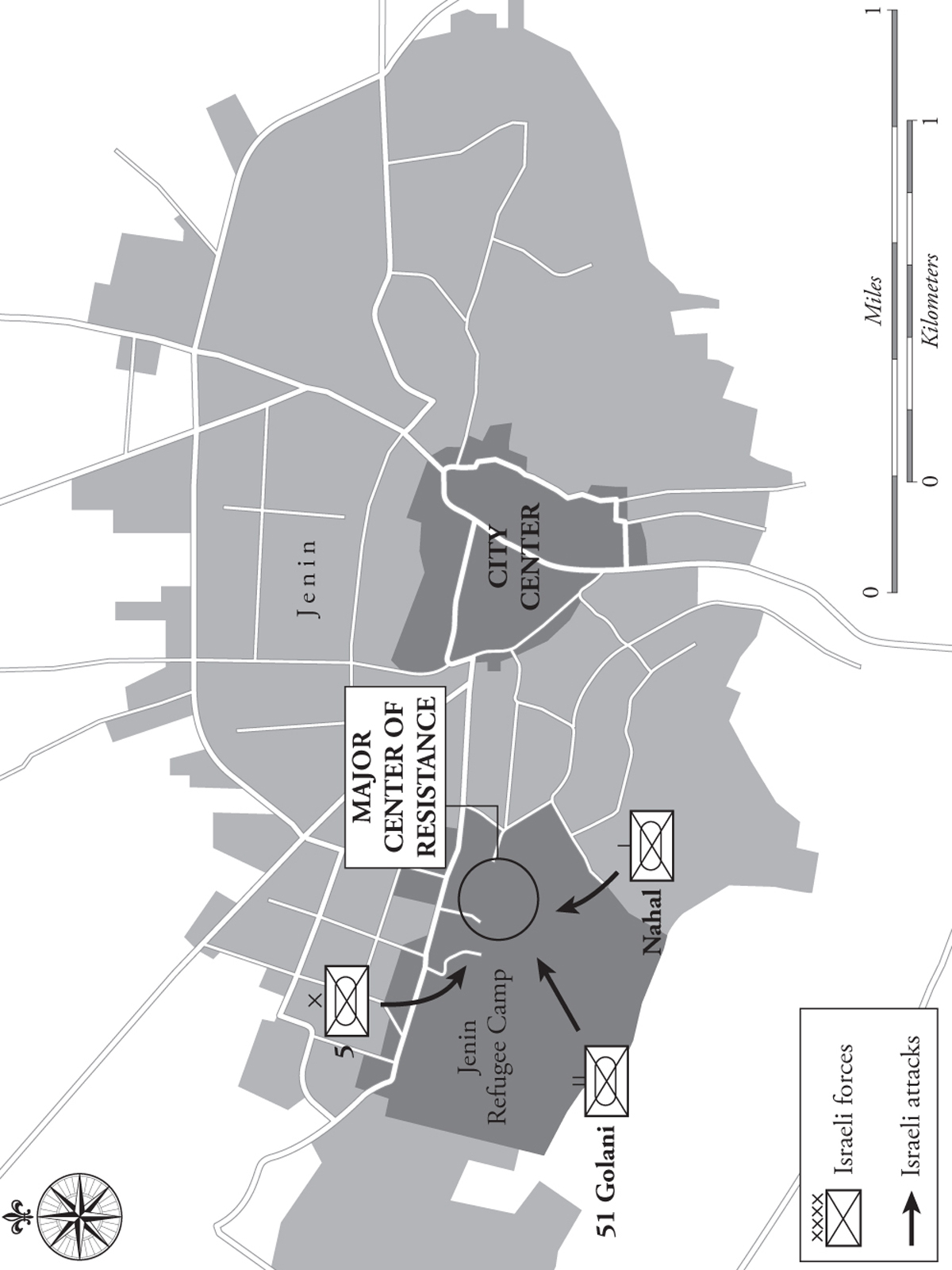

Operation against militants in Jenin began on April 2, the day before the attack at Nablus, with IDF forces moving into the city and sealing it off from outside communications and support. Of the two cities, the IDF analysis was the Jenin operation would be the easier to accomplish: the city was not nearly as big as Nablus, it was very close to the Israeli border, the refugee population was less than half the size of that in Nablus, and all the refugees were located in a single camp. Because of these considerations, the forces assigned to Jenin were not as robust: the mission was assigned to a reserve division commanding the 5th Reserve Infantry Brigade, reinforced by a battalion from the Golani Brigade as well as special forces, armor, and engineers.

The IDF forces operating in Jenin were organized under Reserve Division No. 340 under the command of Brigadier General Eyal Shlein. The 5th Reserve Infantry Brigade and a battalion of the Golani Brigade occupied the city of Jenin on April 2, 2002, and by the end of the first day they had the bulk of the city under control. That was the prelude to the major part of the operation which was to move into and establish control of the Jenin Refugee Camp. The Jenin Refugee Camp was located in the southwest portion of the city; it was only about 0.5km2 (one-fifth square mile). Access into the refugee camp was carefully controlled by a consortium of Palestinian militant groups who had erected barricades and checkpoints on every avenue into the camp. On April 2, using loudspeakers, the IDF broadcast its intention to occupy the camp and requested all civilians leave the area of military operations. Most of the camp’s 16,000 residents chose to evacuate the camp, however many did not leave until the lead army units began to move into the area. Still, 1,000–4,000 civilians remained in the camp throughout the fighting, alongside several hundred dedicated militant fighters.

The several hundred fighters in the city of Jenin were different from any other group of fighters yet met by the Israelis during Operation Defensive Shield. Though, like the militants in the other cities, they comprised members of Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade, Islamic Jihad, Hamas, and the Palestinian Authority security forces, this group within Jenin decided to subordinate themselves to a unified command inside the camp. This unusual situation was due to the presence of Abu Jandal, who was a uniquely capable and charismatic leader. He was a veteran of the Iraqi army, had fought in Southern Lebanon, and was the leader of the coalition of the various militant groups in Jenin. He understood that though it was impossible to beat the Israelis militarily, it was very possible to achieve a strategic political victory in Jenin, while losing the tactical battle in the camp. To do this they needed to make the taking of the camp a lengthy, and most importantly, casualty-producing battle for the IDF.

On April 3, after completely isolating the city from all outside communications and access, including ensuring that no media organizations had access to the operation, the IDF entered the camp. The 5th Brigade moved into the camp slowly and methodically from the northeast. They were very wary of exposing themselves to casualties. Many of the reservists were less than enthusiastic about being called to active service with no notice, and some disagreed with the political policy behind the operation. They were also nervous because they had almost no training in urban warfare techniques. At Nablus a reserve tank crew had refused to obey orders to attack into the city because they felt unprepared for urban battle. A brigade commander eventually convinced the soldiers to go into battle. At Jenin there were no combat refusals, but the 5th Brigade’s officers were very conscious of the soldiers’ lack of training in urban combat. The brigade also had leadership challenges. The brigade commander had only taken command of the brigade a few days before the operation began. On the first day of operations in the city a very experienced company commander was killed by a militant. This resulted in the officers approaching the battle with even more caution than usual, and the 5th Brigade advanced slowly and methodically throughout the battle.

As the 5th Brigade moved slowly and steadily to breach the perimeter of the camp, the IDF complicated the defenders’ problems by launching another attack from the southwest. This attack was conducted by Battalion 51 of the Golani Brigade. In addition, a company from the Nahal Brigade attacked the camp from the southeast. Both of the main attacks, the 5th Brigade and the attack of Battalion 51, were supported by special forces and air force Apache attack helicopter. Elements of the elite Shayetet 13 (naval commandos) and Duvdevan (counterterrorist commandos) special forces units were operating in the city as well. However, jet aircraft support and artillery support, as in Nablus, were prohibited.

9.2 The IDF Attacks Nablus, April 2002

IDF special forces conducted two broad types of missions in the urban fight. One type of mission was in direct support of the attacking conventional infantry brigade. In that role the special forces would overwatch the regular infantry and armor movement with snipers. Typically, snipers were deployed in a good vantage point 500 meters (1,640ft) or more to the rear of the conventional troops moving forward. From their position they were able to engage any opposing snipers or gunmen firing at the conventional force. They were also in an ideal position to engage any militants attempting to flee in front of the conventional infantry attack. This type of mission was conducted by either an elite army-level special forces unit or, more typically, the brigade reconnaissance company which was an elite unit in all Israeli brigades and had special forces training and capabilities.

The other type of missions conducted by special forces as part of the urban battle were much more specialized, and generally limited to the elite national-level special forces units. These types of missions could include assaults to capture or kill major militant leaders, or to rescue hostages. Israeli special forces also conducted covert missions. In these missions they drove specially outfitted civilian cars, wore civilian clothes, and blended in with the Palestinian civilian population. Usually, but not always, in this covert role the missions were limited to reconnaissance and information gathering.

Two other important units employed as part of the Jenin operation were army engineers equipped with Caterpillar-built D9 armored bulldozers, and Merkava tanks of the armored corps. These heavy armored elements were employed in a manner similar to their use in Nablus. The D9R dozer made by the US Caterpillar Corporation was not a purpose-built military vehicle but rather a very powerful civilian construction bulldozer. The vehicle was 13 feet tall, and 14.7 feet wide with its standard blade; it weighed 54 tons, and was powered by a 405hp engine. The D9’s first major military use was during the Vietnam War when the US Army used them to clear jungle. The Israeli military added massive armored plating to the machines to give them the capability to work while under fire. Israeli soldiers nicknamed the giant bulldozers “doobi,” which translates to “teddy bear.” Its armor protection could deflect all small-arms fire and even rocket-propelled grenades. There are reports that D9R dozers survived improvised explosive device (IED) attacks by bombs weighing as much as 440lb and 1,100lb. The initial advance into the refugee camp began with an armored bulldozer clearing the three-quarter mile approach to the camp. During that operation an engineer officer noted that the dozer set off over 120 IEDs without sustaining significant damage.

The 5th Brigade entered the camp dismounted. The Palestinian militants were surprised, and pleased, that the Israelis did not lead with armored vehicles. The decision to begin the attack on foot was to minimize civilian casualties. For three days the Israeli infantry slowly and methodically advanced. Their movement was greatly hampered by the extensive mining that the Palestinians did on all approaches into the camp. Militant fighters reported that they deployed 1,000–2,000 IEDs. Some were large antivehicle devices but most were small, about the size of a water bottle, designed to kill infantry. The militants’ objective was to inflict as many casualties as possible on the IDF, and their main method of doing that was by setting up booby-traps throughout the camps. In particular the Palestinians booby-trapped the major alleyways, doors and windows to houses, cars, and the interior of houses. Inside houses IEDs were placed in doorways, cabinets, closets, under and inside furniture. They concentrated their booby-traps in abandoned houses, or in the homes of prominent militants that they were sure the Israelis would search. In the first three days of the battle little progress was made into the camp, seven IDF soldiers were killed, and in some cases units only advanced at a rate of 50 yards a day.

The IDF estimated that the Jenin operation would take 48–72 hours to complete. By April 6 they were four days into the operation, units were still only advancing very slowly against very stiff opposition, and casualty rates were much higher than expected. Israeli army headquarters began to put pressure on the division commander to pick up the pace of operations. The IDF had a long history of rapid, decisive operations. Speed was a highly valued quality because with it came surprise and the shock effect. The IDF was also concerned with speed for strategic reasons. The history of the wars between Israel and its Arab neighbors indicated that in any major military operation, especially if it was successful, international and United States diplomatic pressure would be put on the Israeli government to end the operation. This pressure would steadily mount until invariably the Israeli prime minister halted the operations. Thus, the Israeli senior commanders understood that the IDF had an unknown but finite amount of time to clear and seize Jenin. If that did not occur before the diplomats halted operations then the operation would fail.

While the 5th Brigade slowly moved ahead, in the southwest Battalion 51 was making better progress. This difference was because the Battalion 51 commander determined to use the same tactics that the Golani Brigade had used in Nablus: leading with D9 dozers, then mechanized infantry in their carriers, and finally, tanks firing in support. However, the slow progress of the 5th Brigade allowed the Palestinians to focus on Battalion 51, and thus, despite the battalion’s aggressive tactics, it was fighting fiercely for every building. On April 8, as fighting ended in Nablus, the Golani Brigade commander, Colonel Moshe Tamir, visited and assessed the situation in Jenin. He recommended that more aggressive tactics, similar to those of Battalion 51, be adopted. Division headquarters continued to emphasize speed to the commanders in Jenin, and set the next day, April 9, as the date the mission had to be completed.

Early on the morning of April 9, a 5th Brigade Infantry Company from Reserve Battalion 7020 moved forward to occupy a building to serve as the base for the day’s operations. As they moved forward, wearing their night-vision devices in the early morning darkness, they diverted from their planned route. As they moved down a 3ft-wide alley between buildings they were suddenly attacked by bombs thrown at them, and small-arms fire. Within seconds, a half dozen soldiers were hit and down, including the company commander. The ambushed element of the 5th Brigade found itself cut off, surrounded, and under intense fire from militant gunmen shooting from upper-story windows. All but three men in the unit were killed or wounded as they sought cover in a small open courtyard. An initial effort to rescue the element inadvertently stumbled into a booby-trapped room and set off an IED that killed two more men and wounded several others.

Unmanned aerial reconnaissance loitered over the firefight and sent real-time images of the plight of the troops to IDF headquarters but the close range of the engagement – the combatants were within 30 feet – prevented the Israeli command from supporting their troops with heavy weapons. In the midst of the fight the Palestinians dashed forward and dragged off the bodies of three Israeli soldiers killed in the fight, with the intent of using the bodies as a negotiating lever at a later date. After several hours of frustrating combat, Shayetet 13 entered the battle and counterattacked to retrieve the bodies. The naval commandos quickly overran the Palestinian militants, retrieved the bodies of the fallen soldiers, and relieved the surrounded force. In total, 13 Israeli soldiers were killed and many more were wounded. It was the largest loss of life in a single day for the IDF in 20 years.

The ambush of April 9 consumed the energy of the Israeli command on that day, and put it further behind its timetable for securing the camp. It also demonstrated that careful, dismounted work in the tight confines of the camp could lead to unacceptable casualties. Thus, when the command renewed the attack the next day the 5th Brigade adopted a much more aggressive approach. On April 10 the Israeli attack was led by D9 bulldozers, followed by infantry mounted in the heavily armored Achzarit personnel carriers. Tanks and attack helicopters fired into buildings ahead of the dozers and infantry to force militants out. The dozers were extremely effective and literally buried any militants who tried to stay and fight in the rubble of their building. Several civilians who were unable to evacuate the area also became victims of the relentless destructive power of the armored bulldozers. When the Israelis estimated that they had arrived at the center of the Palestinian defensive network, they unleashed the full capabilities of the dozers which, under the covering fire of infantry and tanks, systematically eradicated a 200m by 200m (650ft by 650ft) square of two- and three-story buildings that formed the heart of the refugee camp. By the end of April 10 the central urban complex of the refugee camp, the center of the militants’ defensive scheme, was reduced to a flat, featureless open area devoid of any structures or cover. The Palestinian fighters had no choice but to retreat in front of the Israeli attack into the last remaining unoccupied neighborhood of the camp.

On April 11 the Israeli forces in Jenin prepared to continue the ruthless onslaught which had carried them into the heart of the camp the previous day. However, as the Israel armored vehicles and infantry prepared to attack, the Palestinian militants in the camp began to surrender. During the day approximately 200 fighters gave themselves up to the Israeli forces. A small number managed to flee though the surrounding Israeli security ring and a few die-hards continued to fight on in isolated pockets, until they were crushed in their buildings by bulldozers. By the end of April 11 the battle for Jenin was over.

In the eight-day battle for the control of the Jenin Refugee Camp the Israeli forces lost 23 soldiers killed and 52 wounded. From a casualty point of view it was the most significant combat action of IDF since the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. Detailed analysis by non-Israeli investigators determined that the defending Palestinian militants lost 27 fighters killed, hundreds wounded, and over 200 were taken prisoner by the IDF. The civilians who remained in the city suffered as well: 23 civilians were killed in the battle, unknown hundreds were wounded, well over 100 buildings were completely destroyed and another 200 rendered uninhabitable, and over a quarter of the camp’s population, over 4,000 people, was made homeless. Still, the IDF was satisfied with the results of the operation. They had killed or captured several key militant leaders, taken into custody hundreds of fighters, and destroyed several bomb and rocket factories. They had also gleaned a wealth of intelligence from interrogations, and captured documents and equipment. Despite their success, however, the IDF made a critical mistake in the operation which would have effects well beyond the immediate objectives of Defensive Shield.

Map 9.3 The IDF Attacks Jenin, April 2002

Before the battle of Jenin was over, the international press began reporting allegations of a major massacre of civilians in the city. As the battle raged, Palestinian officials, citing reports from civilians who evacuated the camp, claimed that the IDF was executing civilians, burying families in their homes, burying bodies in mass graves, summarily executing fighters and civilians alike, and firing rockets into homes. The accusations were widely reported in the international press and though it was reported that the accounts were not verified, they were widely accepted as being at least based on truth. Lending credibility to the accusations was the IDF’s complete exclusion of the media from the battlefield. Several early inaccurate statements by Israeli officials alluding to significant civilian casualties fueled media speculation and Palestinian accusations. Vague official statements from the IDF did nothing to put down the rumors. Several international organizations including Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International (AI) began to collect witness statements from civilians before the battle was over and had teams prepared to enter the camp as soon as the IDF permitted. On April 18, the first team from AI entered the camp and made an initial assessment that there was a strong possibility that the accusations were true. Over the two months following the battle, AI, HRW, the UN, and several news services including CNN and the BBC all did detailed investigations. The systematic and thorough investigations revealed that rather than a massacre, the IDF description of events as a battle between the IDF and Palestinian militants was substantially true. The independent organizations all confirmed that the casualties, of all types, reported by the IDF were generally accurate.

Though the investigations eventually confirmed the IDF version of events, the fact that the investigations were necessary was a result of the IDF policy of isolating the battlefield from media coverage. Denied the ability to cover the battle, the media reported the only information it had available, which was the sensational and ultimately highly inaccurate accounts of a massacre presented by the Palestinians. Once the story made headlines around the world, the damage was done. International pressure on the Israeli government increased dramatically and the legitimacy of the mission was questioned by many countries, including Israel’s chief ally, the United States. Once the massacre stories were published they became the accepted narrative of the battle for many audiences, despite the findings of subsequent investigations. For the Palestinians the massacre story was generally accepted as true and Jenin became a rallying cry for the Palestinian cause, a source of endless propaganda, and a major recruiting tool for the ranks of militant fighters.

In the battles of Operation Defensive Shield, the Israeli Defense Forces demonstrated a solid basic capability to conduct operations within the extremely dense urban environment of West Bank cities and refugee camps. Many tried and true urban combat techniques continued to be effective and necessary to success. The battles in the refugee camps also demonstrated new capabilities and threats in the urban environment. Finally, they reflected the continued importance and growing necessity of urban combat.

The Israeli military had very powerful and professional armored forces, as necessary to fight the conventional threats presented by the Arab countries on its borders. The traditions of armored combat influenced the Israeli tendency to prefer armored forces in the urban environment. The successes of Israeli armor and mechanized forces in 2002 demonstrated that the protection, firepower, and psychological effect of armor in a city remained a great advantage. Using armor also mitigated the number of casualties suffered by the attacking forces, a critical consideration for a small force like the IDF. Unlike the Russian initial deployment in Grozny, however, Israeli tanks operated in close coordination with a screen of protective infantry. Operation Defensive Shield also demonstrated one particularly important disadvantage of armor in a world dominated by global news coverage: the amount of collateral damage, including civilian casualties, that results whenever armor is operated aggressively in a city where a civilian population is still present.

The extensive use of D9 bulldozers by the Israeli military was a unique characteristic of Israeli urban warfare. The IDF used the dozers to somewhat compensate for the lack of available artillery and airpower. The dozers gave the Israelis the ability to precisely destroy enemy positions which, in a less constrained combat environment, would have routinely been subject to artillery and air attack. The D9s proved, however, to be highly controversial. Many civilian casualties were attributed to the bulldozers and they also destroyed a large number of buildings during the campaign leaving thousands of civilians homeless. The use of the D9 dozers meant that the IDF incurred the animosity of the Palestinian population for many years to come.

The Israelis also made extensive use of Apache attack helicopters in support of their ground troops. In the IDF, helicopters are operated by the Israeli air force. There were no reports of helicopters being lost to ground fire which implies that the aircraft were employed very carefully, and fired from positions already secured by IDF ground forces. American experiences with helicopters in urban operations – Mogadishu, Somalia (1993), and Panama City, Panama (1989) – indicated the significant vulnerability of helicopters to ground fire when operating over cities. This different experience was likely because the Americans, whose helicopters are part of the army maneuver forces, integrate helicopter operations very closely into ground maneuver operations as both an attack platform and as transport, and thus expose the aircraft to greater risks.

As in all previous urban operations, intelligence was a key to success. The battle for Jenin demonstrated how difficult it is, for even an excellent intelligence service like that of the IDF, to penetrate into a hostile urban environment and accurately determine important tactical details. Remote sensors in the form of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) greatly increased the tactical situational awareness of IDF commanders and allowed them to shift forces to meet threats. As the battle progressed, intelligence support to the attacking Israeli ground forces improved. This was because the IDF created tactical interrogation units that questioned captured militants and civilians as soon as they came under IDF control. These intelligence units were organized to both send the acquired information up the chain of command, and – importantly – quickly send new and important information directly back to the units in combat.

A final important aspect of the Israeli success in the urban battle of Operation Defensive Shieldwas the use of special forces. The Israelis employed relatively large numbers of special forces to the urban battles of March and April 2002, particularly the operations in Nablus and Jenin. These included the reconnaissance companies of each brigade which were trained in special forces tactics such as sniping and covert reconnaissance. Thus, the defending Palestinians had to not only contend with brute force conventional threats like the D9 bulldozers and Merkava tanks, but also the equally deadly special forces snipers and raiders.

The D9 dozer was a new urban weapon employed by the IDF. On the Palestinian side they employed an old weapon, the booby-trapped IED, but they did so in unprecedented numbers. With just a little time to prepare, the militants were able to distribute thousands of devices, and in doing so they significantly slowed the advance of the IDF infantry. IDF engineers, both dozer operators and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) specialists, were critical to maintaining the momentum of the attack. The IDF learned that they did not have enough specialist EOD personnel, and thus after the battle they increased the emphasis on EOD training among their infantry.

Though the IDF was sensitive to civilian casualties, and no massacre occurred in Jenin, it is important to understand the type of military operation that the IDF was tasked to accomplish during Operation Defensive Shield. By going into the urban areas of the West Bank, the IDF was invading the urban centers of a foreign, and generally hostile, population. The West Bank was not part of Israel, and at the time of the operation it was under the political control of the Palestinian Authority. Thus, the operational context was more like the Russian army in Grozny than the British in Northern Ireland or even the French in Algeria. In both the latter cases, the military had the objective of eliminating the urban enemy while at the same time not alienating the urban population, who were citizens of the United Kingdom and France respectively. The IDF’s operational concern with civilian casualties was more out of respect for the law of war and international opinion, than the military and political objectives of the campaign. Thus, they were comfortable emphasizing speed, firepower, and armored forces, and destroying as many buildings as necessary to achieve the military objective, as long as the laws of war were observed. Thus, the IDF perspective of the battle was as a battle against a security threat to Israel. The enemy was a guerrilla force hiding among a sympathetic enemy population in a foreign city.

For their part, the Palestinian defenders, though hopelessly overmatched by Israeli military power, demonstrated – as the Chechen fighters had – that adroit manipulation of the information spectrum could yield some positive strategic results even when the outcome of the conventional military battle was a foregone conclusion. The Palestinians were aided in this by the Israeli forces, who demonstrated no understanding of the vital importance of engaging the enemy in the information spectrum of war.

The Palestinian capacity for attacking Israel was significantly diminished by the urban battles of 2002, but not eliminated. The battles were not meant to, and the IDF was not capable of, eliminating the reasons behind the Intifada. Therefore, as soon as the IDF withdrew, and the militants acquired and trained new recruits, the Intifada continued. The Israeli–Palestinian war would not end until 2005. The best that Operation Defensive Shield could accomplish was reducing the Palestinian militants’ capability to conduct terrorist attacks inside Israel. It accomplished that goal and therefore was a successful operation.