When the 1st Brigade Combat Team (1BCT) of the US Army’s 1st Armored Division (AD) received its orders sending it into western Iraq in June 2006, it was one of a long list of army and US Marine combat units assigned to operations in Iraq’s Al-Anbar Province since the US invasion of Iraq in March 2003. There was no reason to believe at the time that the operations of the “Ready First” Brigade in the provincial capital of Ramadi would be any more decisive or exceptional than the operations of previous units. What happened in the next nine months, however, became the greatest success story of US arms to come out of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Between the summer of 2006 and the spring of 2007, the deadliest city in the most dangerous anti-US province in Iraq was not just pacified, but became the model for successful urban counterinsurgency for the rest of the war in Iraq, as well as for operations in Afghanistan.

The US military came to Al-Anbar province in the last days of the initial invasion of Iraq, known as Operation Iraqi Freedom One (OIF1). Al-Anbar was far from what the US command viewed as the decisive point of the operation, the city of Baghdad, and so it was not critical to the invasion. The only decisive combat action that took place in the province in the initial weeks of the war was the seizure of the Hadithah Dam by the US Army’s 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. It took the Americans several months to realize the unique significance of Al-Anbar Province.

Al-Anbar Province, with a population of 1.23 million people, was the largest province geographically in Iraq, and was the only province dominated by Sunni Muslims, who comprised 95 percent of the population. Because it was dominated by Sunni Arabs, the province was favored by Saddam Hussein, and was a bastion of Ba’ath party support. It was also home to a large percentage of the Iraqi army’s leadership. Because of its close affiliation with the Ba’ath Party and the army, and also because it was relatively untouched by the initial invasion and thus not exposed to the capabilities of the US military, it became the natural refuge of those fleeing Baghdad and bent on resisting the American occupation of Iraq.

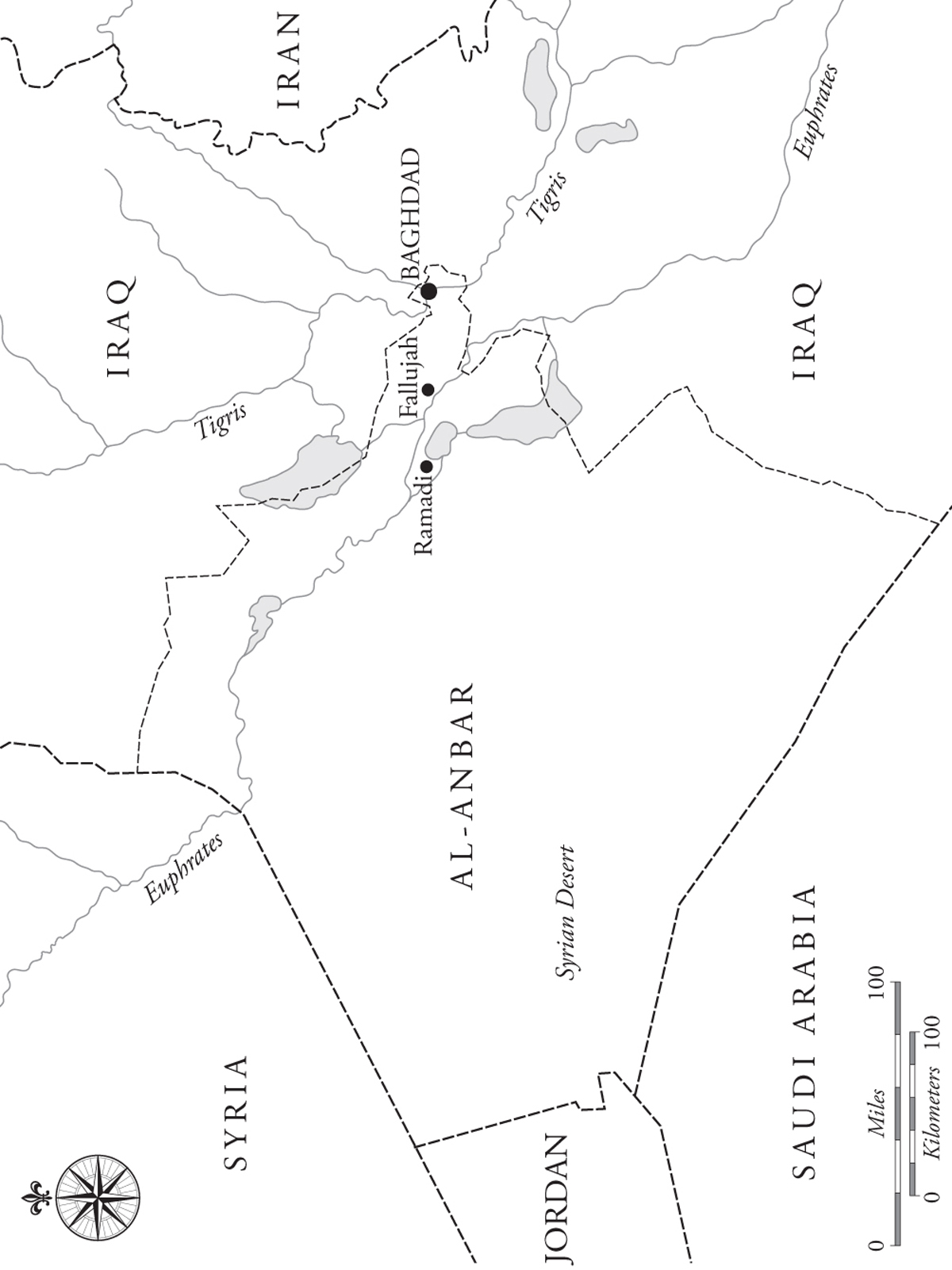

Al-Anbar Province was the largest in Iraq, at 53,370 square miles, about the size of the American state of North Carolina, and it was located in the southwest corner of Iraq. The vast majority of the southern portion of the province was part of the Syrian Desert, which extended across the province’s borders westward into Syria and south into Jordan and Saudi Arabia. The northern fifth of the province was a strip of land to the north and south of the Euphrates River. This strip includes the major cities of the province, the agricultural areas, the history, and the bulk of the population. The two largest cities of the province, Fallujah and Ramadi, were located in this area.

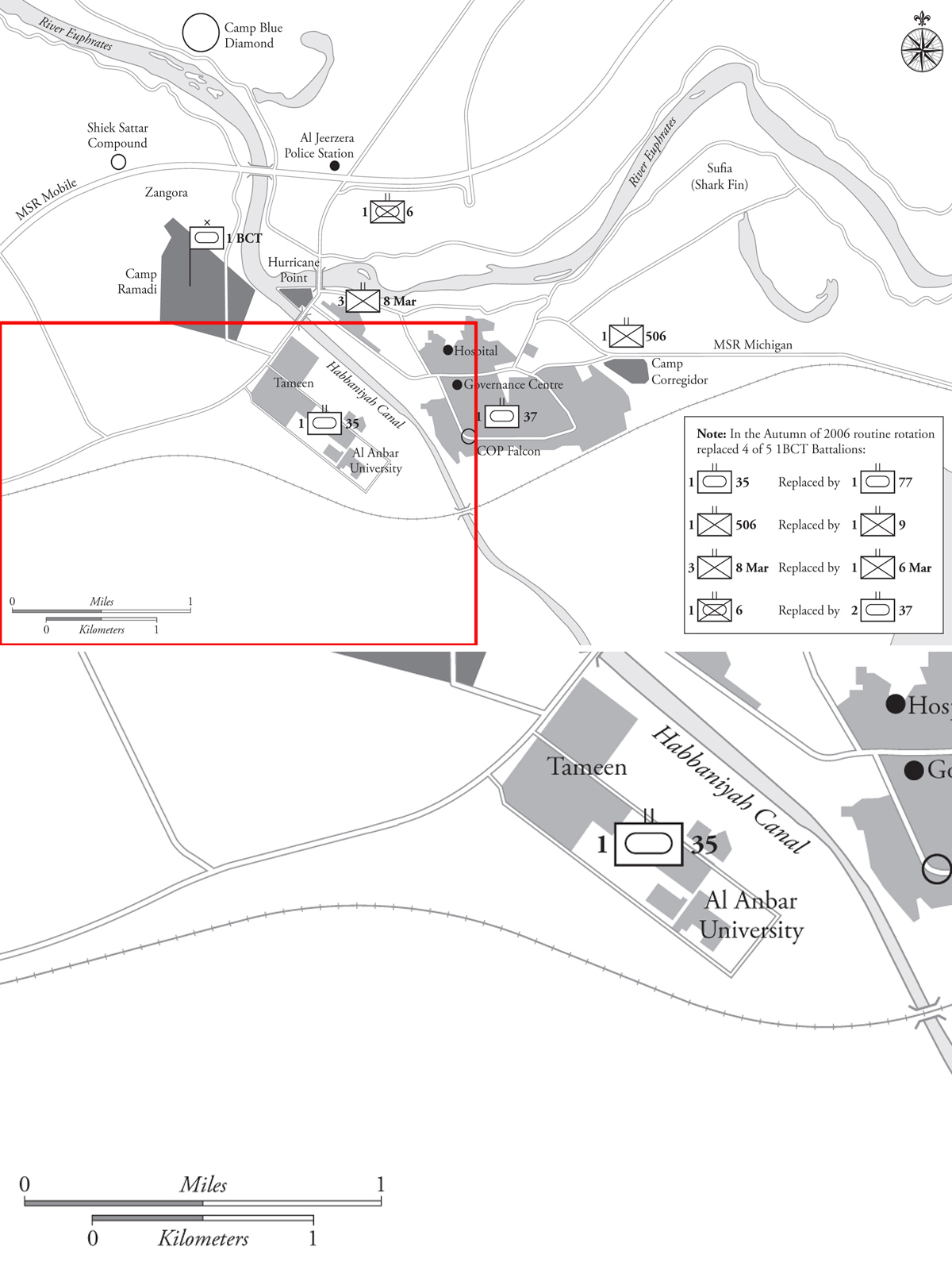

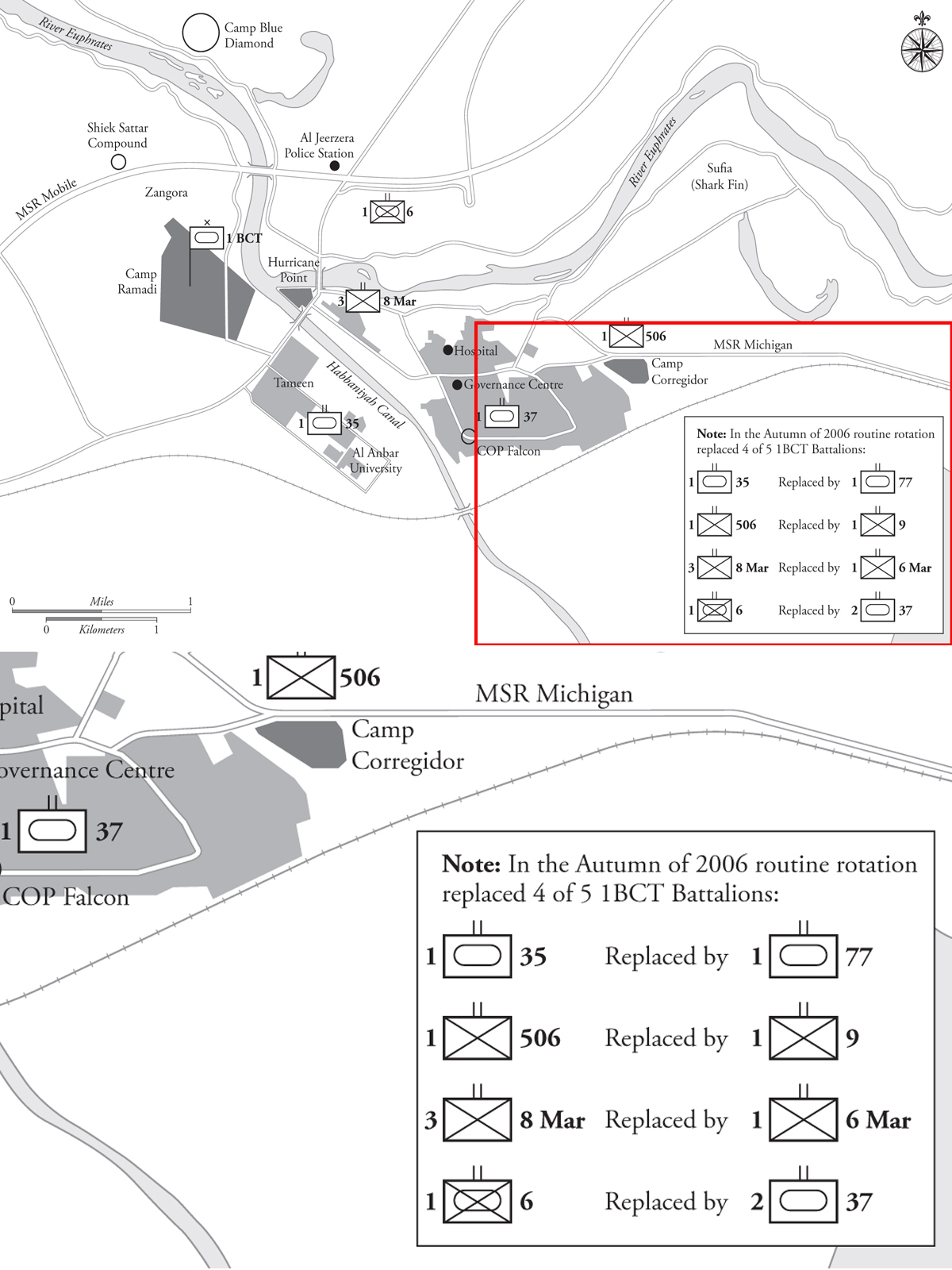

The largest city in the province was the provincial capital, Ramadi. Ramadi was a relatively new city in the region, established by the Ottoman Turks in 1869 to control the Iraqi Dulaim tribe. The city and its major suburbs were relatively large, about 15km (11 miles) east to west and 12km (9 miles) north to south. It had a population of between 400,000 and 450,000 at the time of the battle (it was about four times the size of Fallujah). The bulk of the city’s population remained in the city throughout the fighting. The city was divided into a dense central city area and numerous suburban residential areas. The central city was bounded on the north by the Euphrates River, on the west by the Habbaniyah Canal, on the south by the railway line, and on the east by suburbs. Major suburbs, in addition to those to the east of the city, were also located west and northwest of the Habbaniyah Canal, and north of the Euphrates River. Two main bridges connected the central city with the suburbs: one crossing the Euphrates River to the northern suburbs; and one crossing the Habbaniyah Canal to the western suburbs. In addition, a major highway bridge crossed the Euphrates north of the city and connected the western and northern suburbs. The suburbs themselves were mainly residential areas, and they were divided into distinct districts, each aligned with a particular tribal group.

Before the US invasion of Iraq the city of Ramadi was a fairly modern Iraqi city. Because of its relatively recent history, Ramadi did not have a casbah as found in traditional old cities of the region. Buildings were predominantly built of concrete and in the central part of the city, they were very modern. The city’s hospital had been built by a Japanese company in 1986 and at seven stories tall was the tallest building in the city. There were several five- and six-story tall buildings in the downtown area. Most of the buildings in the city and in the suburbs were traditional flat-roofed two- and three-story cement buildings. By the time the 1BCT arrived at the city, considerable fighting had occurred in the years since the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The central part of the city had been subjected to numerous artillery and air attacks, and improvised explosive device (IED) explosions were a regular occurrence on all of the city’s main streets. For example, the city hospital had been regularly attacked by US Army multiple-launched rocket systems (MLRS). There was significant damage to the city center, many buildings were destroyed, and many more were damaged and uninhabitable. There were few undamaged buildings.

The roads of Ramadi were paved, but over the years debris, dirt, and garbage had accumulated on top of the paving. When the 1BCT arrived in the city they were covered with inches of grime. In addition, most of the city’s infrastructure no longer existed. There was no power in the city, there was no garbage removal, many areas did not have running water, there was no telephone service (including no cell-phone service), and no operating newspapers. There was also no mayor or city council. The police force of the city consisted of 100 policemen, who never left their stations and often did not report for work. Essentially there was no functioning government.

The area of operations (AO) assigned to the 1BCT, AO Topeka, was slightly larger than the city and included another 150,000 civilians in addition to the population of Ramadi itself. This rural population was scattered among numerous small villages on the north and south banks of the Euphrates River. The vast majority of the people in and around Ramadi were from the Dulaim tribe confederation. The Dulaim, its subordinate sub-tribes and clans, made up 10–20 percent of the Iraqi army and were particularly prominent in the elite Republican Guard units. There were over a thousand clans within the Dulaim, and the tribes’ membership extended over the international borders into Syria and Jordan. Each tribe within the Dulaim confederation was headed by a sheik. The sheiks were secular leaders, usually selected by the tribal elders through a process that was unstructured, but based on heredity, competence, and democracy. The sheik’s responsibility, in return for the loyalty of the tribe, was to ensure the security and well-being of the tribe, while also administering tribal justice. Seniority among sheiks was based on tribal wealth, measured in actual wealth, political influence, and the size of the tribe. Dozens of sheiks oversaw the tribes living in Ramadi and the surrounding area. Many of the most important sheiks oversaw their tribes from self-imposed exile – for reasons of safety – in places like Jordan.

Map 10.1 Al-Anbar Province, Iraq, 2006

In Al-Anbar Province the US forces and the security forces of the new government of Iraq (GOI) faced at least three diferent types of opponents. The frst was Al Qaeda of Iraq (AQI), which was the most dangerous and ideological of the groups. The second were the Sunni nationalists who had been favored under Saddam Hussein and who had lost political power with the invasion. Finally, there was an unorganized criminal element that was bent on profiting from the general violence and lawlessness. The prime objective of coalition forces in 2006 was AQI, and those Sunni nationalist groups and criminal elements that supported AQI.

Al Qaeda in Iraq was organized in 2003 as part of the reaction to the US invasion. It was nominally a division of the larger Islamist Al Qaeda organization led by Osama Bin Laden and based in Pakistan. The leader of AQI was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was a Jordanian. The size of the organization was unknown, but estimates ranged from 800 to several thousand fighters. Many of the group’s members were foreigners who infiltrated into Iraq from Syria, but it also contained many radical Iraqi Islamists. Its leadership, however, was dominated by non-Iraqis. The goals of AQI were to force the US forces to leave Iraq, defeat the Iraqi security forces, overthrow the Iraqi government, and establish an Iraqi Islamist state. In October 2006, in the midst of the battle for Ramadi, AQI declared the Islamic State of Iraq with Ramadi as its capital. AQI employed a variety of hit-and-run guerrilla tactics against coalition forces, but uniquely favored the vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), and the suicide bomber.

The other major group of insurgents were the Sunni nationalists. These fighters’ loyalties were first to their sheiks and tribe, and second to the former Ba’athist government of Iraq. Many of them had had high rank and extensive military experience in the former Iraqi army or in other aspects of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence and security apparatus. They considered themselves legitimate resisters of the foreign occupation and the Shi’ite-led Iraqi government. Through their tribal affiliations they had widespread popular support.

Both the Islamists and the nationalists were supported by criminals who hired out their services for pay. These criminals typically operated in small independent groups and were willing to snipe, emplace IEDs, and even attack Coalition Forces (CF) positions for predetermined payments. Bonuses were paid to these groups for the success of their operations and often they were required to show video evidence in order to be paid. In the first years of the Iraqi insurgency, 2003–05, the two major factions of the insurgency, Islamists and nationalists, worked together against the Coalition Forces. However, in areas where they had dominance, the Islamists, primarily AQI, began to enforce strict Sharia law. They arbitrarily killed or mutilated violators of strict Islamic law, and also began to demand both material and monetary support from the local populations. Anyone who protested against, or resisted, AQI demands was summarily executed. By the end of 2005 the nationalist Sunni resistance leaders realized that AQI were potentially a larger threat than CF. However, it was difficult for the nationalists to resist AQI’s dominance because the nationalist sheiks were not unified, and AQI used highly visible executions to intimidate large portions of the population.

In the spring and summer of 2006, Iraqi nationalist insurgents and AQI controlled virtually all of the city of Ramadi. Insurgents could openly travel almost anywhere in the city, in groups, and carrying their weapons, without fear of CF or police notice, attack, or reprisals. CF estimated that in the summer of 2006 there were a total of about 5,000 insurgents active in Ramadi.

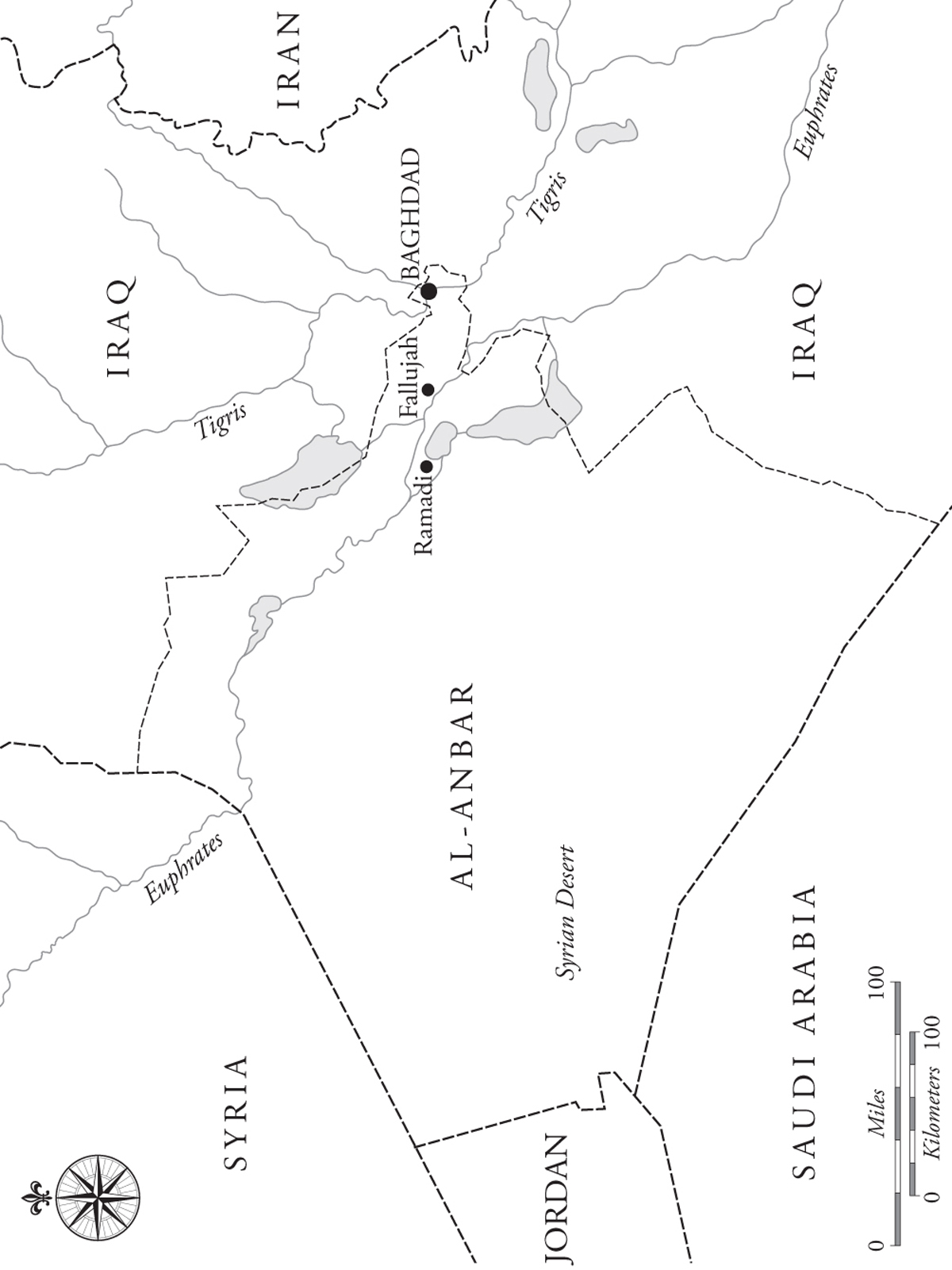

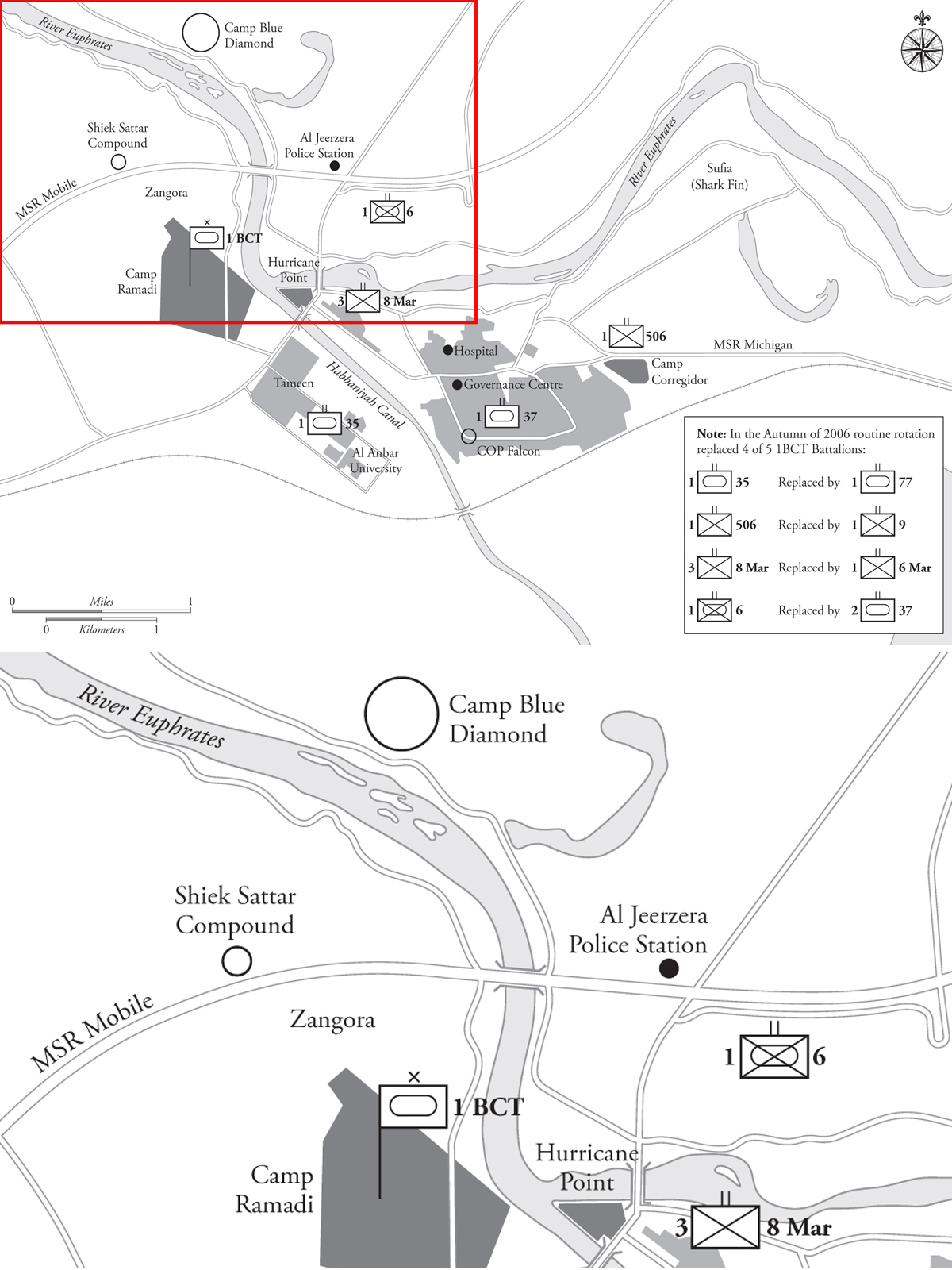

The 1BCT relieved the 2BCT, 28th Infantry Division, a brigade from the Pennsylvania National Guard. The 2BCT, over its year-long deployment, 2005–06, kept the two major supply routes (MSRs) –Route Michigan and Route Mobile – through the Ramadi area open, and protected itself and the main government complex in the center of the city. However, it had done little else to improve the US position in Ramadi. As the BCT redeployed, two regular battalions working in the city remained in the area and came under 1BCT control. The first of these was the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines, whose major job was protecting the government building in the city center. The Marines operated out of Hurricane Point, on the northwest side of central Ramadi. The other was the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry, who had responsibility for the east side of Ramadi and access from that direction. They operated out of Camp Corregidor just south of Route Michigan on the east side of the city.

The 1BCT, under the command of Colonel Sean MacFarland, arrived in Iraq in January 2006 configured as a typical cold war US armored brigade. It contained two tank battalions and a mechanized infantry battalion, with supporting elements that included a combat engineer battalion, an artillery battalion, a support battalion (medical, maintenance, and supply), a reconnaissance troop, an intelligence company, and a signals company among others. Immediately after arriving in theater the BCT lost its mechanized infantry battalion on a separate mission. It then proceeded to relieve the 3rd Cavalry Regiment in Tal Afar. For five months it operated in Tal Afar under the operational control of the 101st Airborne Division. In May it was ordered to Ramadi to relieve the national guard and took control of AO Topeka in June. It left one armored battalion in Tal Afar to provide heavy armor to the Stryker brigade that assumed control of that city.

Operations in Al-Anbar Province were under the command of Major General Richard Zilmer, US Marine Corps, and the 1st Marine Division. The 1st Marine Division, acting as a joint (multiservice) and combined (multinational) command – Multinational Forces West (MNFW) – commanded all ground military forces in the province. As the 1BCT moved from its positions in Tal Afar to Ramadi it moved from under the command of the 101st Airborne Division to MNFW. The BCT arrived in Ramadi in late May with only one of its original three combat battalions. It was then augmented by battalions remaining in Ramadi as well as the Central Command operational reserve so that when it began operations it had five combat battalions under its command.

The 1BCT’s initial deployment committed all five of its combat battalions to operations. The 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry (TF 1/6), operated out of Camp Diamond and was responsible for Ramadi north of the Euphrates River. The 1st Battalion, 35th Armor (TF 1/35) operated out of Camp Ramadi, a Saddam Hussein palace compound on the west side of the Habbaniyah Canal, just northwest of the central city. It was responsible for Ramadi west of the canal. The 1st Battalion, 37th Armor (TF 1/37) also operated out of Camp Ramadi, but was responsible for southern Ramadi east of the canal. The 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines (3/8 Marines) operated out of a combat outpost (COP), Hurricane Point in the northwest corner of the central city, and had a company permanently stationed at the central government complex in the center of downtown. The 1st Battalion, 506th (1/506) Infantry was stationed at Camp Corregidor on the east side of the central city and was responsible for the eastern portion of the city and area of operations. In total the BCT had over 5,000 personnel, 84 Bradley Fighting Vehicles, and 77 M-1 Abrams tanks under its operational control in AO Topeka.

In addition to the ground-combat battalions at its disposal, the 1BCT included the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery. That battalion was given two tasks: develop and supervise a close-combat training program for the Iraqi army (and later police), and provide indirect fire support to the maneuver battalions in the city. The 16th Engineer battalion was designated to provide combat engineer support to the maneuver battalions, including the building of COPs. Two additional attachments to the BCT gave the brigade unusual capabilities. One of those detachments was two platoons of US Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) teams. These two SEAL platoons gave the BCT its own special operations capability. The other attachment was a section of Small Unit Riverine Craft (SURCs) which belonged to the navy but were operated by the Marine battalion. The SURCs were used to patrol the Euphrates River and Habbaniyah Canal, they were able to search watercraft, look for swimmers, and also to insert and support patrols and snipers. This capability facilitated the BCT’s ability to maneuver by water around Ramadi, avoid IEDs, and denied the waterways to the insurgents.

Though, geographically the US forces were well positioned to surround the city, in May 2006 operations were limited to securing the bases, and the central government complex downtown. The forces in and around Ramadi did not have the combat power to seize the city from AQI control. In the spring of 2006 the MNFW asked for a considerable additional number of troops to replace the 2BCT, 28th Infantry Division. They got 1/1 BCT. They wanted light infantry, they got a heavy armored BCT. They were told by their higher headquarters that commanders would get what they asked for, but they didn’t. The 1BCT had five maneuver battalions available for operations in and around Ramadi. Ramadi was four times the size of Fallujah, yet in comparison, during the second battle for Fallujah, in November and December 2004, the US Marines employed eight battalions, of which two were mechanized and the other six were large Marine light infantry battalions.

However, comparisons with Fallujah were not important because the 1BCT’s specific guidance from the MNFW was to “Fix Ramadi but don’t do a Fallujah.” The spectacular destruction, civilian casualties, and high allied casualties that characterized the battle for Fallujah were not acceptable in the battle for Ramadi. The 1BCT was prohibited from executing a street-by-street, block-by-block, conventional approach to securing Ramadi, even if they had had the combat power to do so. Another approach was called for.

Overall the US and theater strategy in early 2006 was to turn the war over to Iraqi security forces so that US forces could begin to disengage and return to the US. Tactically, this translated into hunkering down on the forward operating bases, taking as few casualties as possible, and giving responsibility to Iraqi forces as they reached appropriate levels of training and readiness. Sometimes, areas were turned over to Iraqi forces regardless of their ability to accept that responsibility. The problem in Ramadi, however, was that the strategy required that an area be under US control before it was turned over to the Iraqi army (IA) or Iraqi police (IP), and Ramadi was not under US control. AQI had control over all areas of the city where US forces were not physically stationed. The 1BCT had to alter these conditions before the area could be turned over to the Iraqi army and Iraqi police.

The 1BCT was assigned two Iraqi army brigades to work with. One brigade was newly formed and proved not to be too valuable in combat. The other brigade had a good deal of experience. Both brigades were very understrength, and the soldiers of both were primarily Shi’ite Muslims – a problem because of the traditional distrust and animosity between the Iraqi Shi’ite and Sunni Muslim populations. The 1BCT assigned the entire newly formed Iraqi army brigade to partner with the US battalion at Camp Corregidor in eastern Ramadi. The more experienced Iraqi army brigade had each of its three battalions partnered with an American battalion: one with 1/6 Infantry north of the river; one with 1/35 at Camp Ramadi; and one with 3/8 Marines in Ramadi. Members of these Iraqi army units participated in all operations conducted by the BCT. Initially there were only approximately 100 ineffective Iraqi police in Ramadi. As more police became available they were also integrated into operations. The Iraqi forces, though not that important militarily, were important politically to the American objective of turning control of Ramadi over to the government.

The 1BCT did not have the combat power to seize a city the size of Ramadi quickly in a single operation. Additionally, the BCT’s guidance was to not conduct a conventional urban attack as had been undertaken in Fallujah. Therefore the BCT determined to seize control of Ramadi using the technique developed by the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment a year previously in the city of Tal Afar. This technique was a phased operation built around several premises. First, the BCT had to disregard the forward operating base (FOB) approach to urban warfare. This approach, conceptually developed before the invasion of Iraq, envisioned basing combat units outside of the urban area and then projecting combat power into the city to achieve very specific effects. It was designed to minimize the amount of urban combat, and the amount of contact between military forces and the civilian population. The FOB approach worked when the combat units were working in support of friendly indigenous forces already inside the city, or when the city was under the control of a conventional opponent who had identifiable critical vulnerabilities that could be attacked. Neither condition existed in Tal Afar in 2005 or in Ramadi in 2006.

The approach to seizing Ramadi determined by the 1BCT was described as “clear, build, and hold.” This later became the central concept of the US surge offensive throughout Iraq in 2007–08. The first step was for US forces to clear a particular discrete subsection of the city. This was accomplished by establishing a combat outpost in the midst of that section of the city. The US forces, supported by the Iraqi army, would then hold that section of the city against counterattacks or infiltration by AQI. As the US forces cleared and held their assigned part of the city, they and their Iraqi partners would simultaneously build institutions and infrastructure in that subsection to win the loyalty of that portion of the city’s population. In this manner, sections of the city would gradually and systematically be brought under US control and then turned over to the government of Iraq and the Iraqi army. This operational technique was time consuming, but it allowed the attacking force to ensure dominant combat power at the point of attack and thereby minimize friendly casualties. The 1BCT determined to conduct one major operation a week to keep the initiative and maintain the momentum of the attack. The pace of the operation was also designed to keep AQI reacting to events, off-balance, and surprised. The goal of the clear, hold, and build strategy was to systematically eliminate AQI and nationalist insurgency dominance of the city and replace their presence with the dominance of Iraqi army and police forces.

The first step in the 1BCT plan was to isolate the city from external support. The concept was not to stop traffic from entering the city, but rather to control traffic coming into the city. This was done by establishing outposts on the major avenues into the city central from the north, west, and east. The SURCs interdicted any waterborne traffic. These operations were to prevent the free flow of supplies and reinforcements into the city and thus prevent large-scale reinforcement of the approximately 5,000 combatants operating in the city. To this end TF 1/35 Armor was assigned the mission of controlling access from the west into the city; TF 1/6 Infantry was given the mission of controlling access to the city from the north; and 1/506 Infantry was assigned to control entry from the east. The 3/8 Marines, inside Ramadi, would continue the mission of securing the government center.

Controlling access into the city was a difficult mission just because of the size of the city and its suburbs and the huge volume of people and goods moving in and out. An example of the size of this task was the area of TF 1/35 Armor, covering the western approaches to the city. The battalion had a total of four combined arms teams (companies) to accomplish its mission. With these small units, it was tasked with securing the suburb of Tameen on the west bank of the Habbaniyah Canal and its population of 40,000, as well as the 20,000 people living north of Camp Ramadi in the Zangora district. To accomplish this mission the TF used a team consisting of a tank platoon, scout platoon, and mortar platoon to operate static vehicle observation posts securing routes Mobile and Michigan in their sector as well as the rural Zangora region north of Camp Ramadi. Two teams – one of mechanized infantry and one tank team – operated in central Tameen. These two units conducted a combination of mounted and dismounted patrols and static mounted observation posts to control the area. They were subject to daily sniping, IED attacks, VBEID attacks, and small-arms fire. Over a six-month period (TF 1/35 redeployed in October 2006), the infantry team took 25 percent casualties during operations in Tameen. However, the teams greatly restricted the ability of AQI to transit and influence their area of operations. Because of the size of the area, the fact that it was a supporting effort to the main operations in the central city, and the low density of troops available, a permanent COP in Tameen was not established until October 2006. Tameen was not completely pacified before the TF redeployed.

On June 7, 2006, a coalition airstrike near Baghdad killed Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of AQI. The 1BCT determined to take advantage of the degradation of the AQI leadership to accelerate the start of operations into the center of Ramadi. On June 14, the BCT ordered TF 1/37 Armor to move across the Habbaniyah Canal and establish COP Falcon in the southwest section of the central city. The was the beginning of the systematic clearing of Ramadi. The operation began with the night infiltration of a US Navy SEAL team into preselected buildings that would be the center of the COP. Seven buildings in total were occupied. Each family was paid $2,500 a month by the US military for the use of the building. The SEALs entered the building, evicted the Iraqis living there, and secured it. As the SEALs secured the building, a route clearance team moved rapidly from Camp Ramadi down the route to the COP, clearing IEDs as it moved. It was closely followed by a tank team. The tank team then linked up with the SEALs and relieved them of responsibility for the COP. The SEAL team then moved out several hundred yards from the COP and set up sniping positions along likely avenues that AQI would use to counterattack against the COP. Meanwhile combat engineers, escorted by mechanized infantry and tanks, moved to the COP with flatbed trucks carrying concrete barriers, generators, building material, sandbags and concertina wire. Power was established, antennae put up, and towers and heavy weapons installed. Within hours the COP was secure, and over the subsequent days the engineers continued to improve the position with more barriers, wire, and other defensive support. Two weeks later the COP was complete with over a hundred sections of concrete wall and 50,000 sandbags. It was invulnerable to machine-gun fire.

An entire US company made COP Falcon its permanent home. In addition, an IA company moved into the COP with the Americans. Eventually the SEALs set up a forward base at the COP. The COP was the base for CF operations in southwestern Ramadi, the purposes of which were to protect the civil population from AQI and its supporters, and to establish control of the area by the government. The COP also became the base for patrolling and intelligence gathering. Both conventional and special operations snipers also operated out from the COP. From the COP the BCT could exert effective control several hundred yards in all directions in the city. In normal operations a span of control of a few hundred yards is not tactically decisive, however, in urban warfare, and in particular in a densely populated city like Ramadi, controlling several hundred yards of terrain brought thousands of civilians and dozens of businesses under the shadow of the BCT’s security. It also subjected all traffic transiting the COP’s area of influence to COP stop and search capability. Thus, the COP Falcon became the first crack in AQI’s control of the Ramadi population.

Over the course of the next nine months the BCT would establish 18 new COPs in Ramadi and through them extend its influence and control, and that of the government of Iraq, into every neighborhood in the city. COP construction became a standard operating procedure (SOP) for the BCT and they became adapt at attacking, seizing, occupying, and reinforcing a COP position in 24 hours. Tens of thousands of sandbags were needed to reinforce the COPs when established. On Camp Ramadi no-one was allowed to eat in the dining facility until they had filled two sandbags and placed them on a pallet before each meal. This policy produced thousands of sandbags a day and when a new COP was established, trucks arrived with pallets carrying tens of thousands of sandbags ready to fortify the position.

The AQI leadership quickly became aware of the threat that the COPs represented, and responded to it. In the case of COP Falcon, the response came quickly as AQI militants moved in small groups to attack the COP. Though quick to respond, the AQI attacks were inept. Most of the attacks never got past the screen of snipers whose purpose was to identify and break up attacks before they got close to the COP. One SEAL sniper team killed 25 insurgents moving toward COP Falcon in the first 24 hours after the army occupied it. Snipers not only alerted the COP of incoming enemy attacks, but also overwatched patrols operating out of the COP.

Intelligence was the key to successful operations and when the 1BCT arrived at Ramadi they had little to no reliable intelligence about central Ramadi. One of the purposes of the COP was to increase the intelligence available to the BCT. This was done through patrolling, and primarily through census patrolling. Census patrols were targeted at a specific neighborhood and their task was to identify all the persons living in that neighborhood, much like a typical government census would do. Knowing the people, where they lived, and who they were associated with in terms of family and tribe was absolutely critical information and could only be gleaned through door-to-door operations. These type of operations also made the CF visible to the population, reassured them of their intentions, and provided the opportunity for the population to provide additional information if they were inclined, without their cooperation being exposed to the insurgents. The BCT used this information to build a human terrain database of the urban battle space which guided subsequent operations and decisions.

Operations to establish the COPs began as soon as the BCT arrived in Ramadi in June, and continued apace throughout the summer at the rate of one new COP about every 10–14 days. It was a slow and systematic pace with the BCT under constant attack from AQI throughout its operations. The COPs were standalone installations, totally capable of defending themselves from attack from any direction, but they needed daily resupply. Much of the BCT’s energy was devoted to protecting logistics convoys moving into Ramadi from IED, grenade, and gunfire attacks. Although these attacks were usually not successful, there were literally dozens a day and they caused all elements of the brigade to operate with patience and caution. The brigade did not have the manpower to operate at a faster pace. This began to change in September 2006.

By September 2006, 1BCT had made significant progress pacifying Ramadi north of the Euphrates and north of Camp Ramadi itself. It had also established a strong presence in Tameen and in the western and southern portions of central Ramadi. But the clear, hold, build strategy was beginning to falter because there were insufficient resources to both clear and hold simultaneously.

An Iraqi government presence was needed to hold territory cleared by CF as they systematically pacified Ramadi through the steady construction and occupation of COPs. Iraqi police were the ideal force to replace the COP once the area was pacified because IP had a legitimate presence in the COP neighborhoods even in peacetime, they had the combat capability to deal with inevitable small-scale insurgent activity, and most importantly, they could be organized and recruited locally. Unlike the Iraqi army forces, which were a national asset and subject to service anywhere in Iraq, the policy of the government of Iraq was to employ police in the area from which they were recruited. Thus, local Iraqi leaders, and CF, could recruit for the Iraqi police and be guaranteed that that manpower would, after individual training, report back to Ramadi for duty. The problem with recruitment, however, was that a recent effort to recruit police had been attacked by an AQI suicide bomber who managed to kill dozens of recruits. In addition, a sheik who supported police recruiting was murdered by AQI. So despite CF efforts to recruit police to back up the operations of 1BCT, the size and effectiveness of the Iraqi police in Ramadi did not change significantly through the summer of 2006.

The police situation, and really, the entire operational situation in Ramadi, changed dramatically in September 2006. The leadership of the Sunni population, 95 percent of the total population of Al-Anbar Province, were the tribal sheiks. Tribal sheiks were the leaders of their tribes and extended families. They were not elected but rather chosen to lead by the tribal elders based on their competence. They had no formal title or position sanctioned by either the new Iraqi government or the regime of Saddam Hussein. Most had had a close relationship with some branch of the former Ba’athist government, and like the general population in Al-Anbar, many had followers who had been important leaders in Saddam Hussein’s military and intelligence apparatus. Many were also involved in low-level illegal activity such as smuggling. These sheiks, whose responsibility was the health and welfare of their tribe, had no great love for the government of Iraq or for CF, but in 2006 they were becoming increasingly estranged from AQI.

Relations between the Sunni sheiks and AQI came to a head in August 2006 when Sheik Abu Ali Jassim encouraged members of his tribe to support the 1BCT in northern Ramadi. Tribe members joined the Iraqi police and manned a police station along MSR Mobile just east of where the main highway bridge crossed the Euphrates River. AQI responded with a coordinated complex attack. They attacked the police station with a massive VBIED at the same time as kidnapping Sheik Jassim, whom they then murdered. Possibly worst of all, they did not return the sheik’s body, thus denying his family the timely burial required by Islam. These attacks were the culmination of a brutal policy of murder and intimidation practiced by AQI against the mostly secular sheiks and their tribes for over a year. They, combined with the operations of 1BCT, drove the sheiks to reconsider their alliances.

One of the reasons that the Sunnis allied with AQI instead of the CF was that in their view, the long-term interests of their tribes lay with AQI. The CF’s consistent message was that they were a temporary presence in Iraq. In contrast, the AQI message was that they were a force in Iraq for good. The sheiks’ interpretation of those messages was that they had to have an accommodation with AQI. The 1BCT brought a different message to their operations in Ramadi. The brigade’s message was that they were in Ramadi to stay until AQI was defeated. Their message to the sheiks was that if they remained loyal to AQI then they would also suffer the consequences. This new message from the CF, combined with the brutality of AQI, convinced one sheik in particular, Abdul Sattar Eftikhan Abu Risha, that the best interests of his tribe lay with the 1BCT. Sheik Sattar came to this conclusion sometime over the summer and began reaching out to the commander of the US forces in his area, Lieutenant Colonel Tony Deane, the commander of TF 1/35 Armor.

The conversations between Sattar and Deane began with the issue of recruiting local police to protect the neighborhoods north of Camp Ramadi. Sattar, who was a minor sheik of a relatively small tribe, understood that by himself he would not be able to alter the balance of power in the city, so he worked behind the scenes with the other sheiks, convincing them that their long-term interest lay with the coalition and cooperation with US forces. His force of personality, despite his minor status, was sufficient that on September 9, 2006 he met with Colonel MacFarland, commander of the 1BCT and presented him with a written pledge declaring the Al-Anbar Awakening. That document, signed by 11 sheiks, pledged loyalty and cooperation to the CF and opposition to AQI. There was some vagueness regarding the government of Iraq in Baghdad, but Colonel MacFarland ignored that and welcomed his new allies.

The Al-Anbar Awakening was a turning point in the battle. The sheiks made hundreds of fighters available as recruits for the IP. More importantly, their tribal neighborhoods immediately became coalition-friendly and IEDs and sniping in those areas ceased immediately. The sheiks contributed a wealth of intelligence on AQI that included safe houses, names of leaders and fighters, supply routes, and weapons caches. They also began an active recruiting campaign to bring more sheiks into the alliance against AQI.

With the support of the sheiks, the 1BCT’s offensive of establishing COPs could continue with new momentum. Though the hundreds of Iraqi police recruits would not be available until they completed weeks of training, the sheiks’ loyal followers instantly became a militia of auxiliary fighters that could control terrain in their own neighborhoods, facilitate the establishment of COPs and take over COPs in the neighborhoods that were now friendly to the coalition. This “flip” by the sheiks took away AQI safe havens, intelligence sources, and manpower. It essentially made AQI militants fugitives in much of Ramadi. In return for the sheiks’ support the 1BCT shared intelligence with them, provided protection and support when necessary, and steered millions of dollars in contracts and business to members of the allied tribes.

The Al-Anbar Awakening was the second disaster for AQI in Iraq, the first being the aggressive determined COP strategy of the 1BCT. AQI recognized the magnitude of the strategic change represented by the Sunni shift in allegiance and attempted to stop it. They attacked the new allies of the coalition to attempt to coerce them back into supporting their ideal of an Islamic State of Iraq. They also stepped up coercive pressure on sheiks who were neutral, or who may have been contemplating switching sides. The battle of the Shark Fin in November 2006 was an example of AQI’s unsuccessful bid to keep the Sunni sheiks loyal.

10.2 Deployment of 1BCT in Ramadi, Iraq, 2006–07

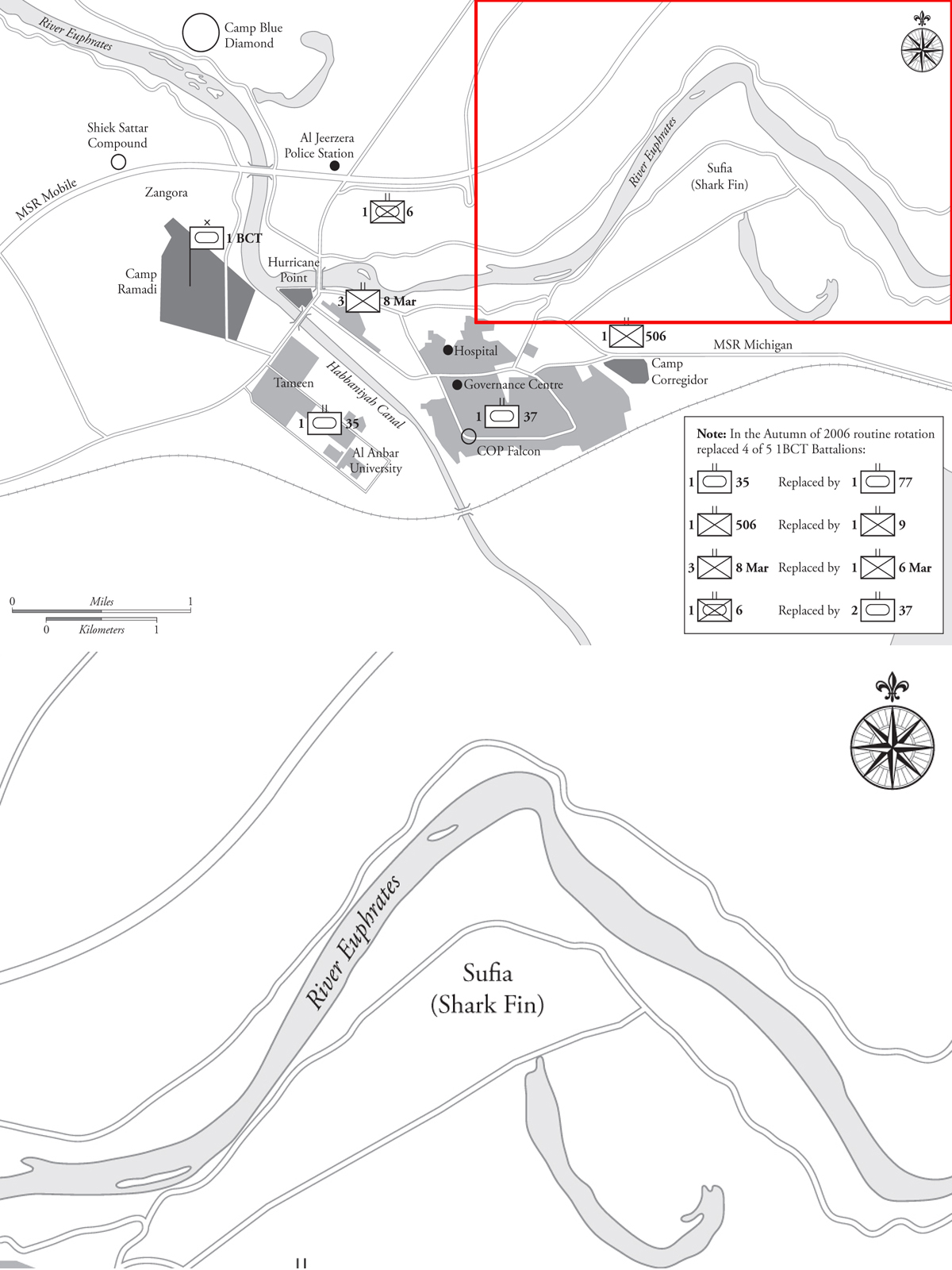

Around 3pm on November 25, Lieutenant Colonel Chuck Ferry, commanding 1st Battalion, 9th (TF 1/9) Infantry at Camp Corregidor (TF 1/9 Infantry replaced 1/506 Infantry in October), received a call from Sheik Jassim Muhammad Saleh al-Suwadawi. The sheik was not a participant in the Awakening, but was one of the group of sheiks who had moved from being an active supporter of AQI to neutral. The sheik was the leader of the Albu Soda tribe, a small group located in an area east of Ramadi and just south of the Euphrates River called the Sufia, known as the Shark Fin by the Americans because of the shape of the bend in the river course. Jassim had been in secret discussions with both the Americans and Sheik Sattar as he contemplated joining the Awakening. He purchased a satellite cell phone so that he could stay in contact with Sheik Sattar. On November 25 he was using that cell phone to report that AQI fighters were attacking his people and he requested the help of the TF 1/9 Infantry to defend the homes of his tribe.

Colonel Ferry did not know Sheik Jassim, and he was in the midst of preparing for an operation to push in the opposite direction, into central Ramadi from the east, but he understood the concept and intent of the 1BCT plan, and thus he made a quick decision to reorient his task force and dispatch a tank and infantry team to support the sheik. At the Shark Fin, more than 50 AQI fighters arrived in several cars and trucks, armed with RPGs and AK-47 assault rifles. They immediately engaged a small contingent of the Albu Soda tribe who were armed but outnumbered. As this was occurring 1BCT moved unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) over the scene and commanders were able to observe by video the firefight going on at the Shark Fin between the followers of Sheik Jassim and AQI. The 1BCT requested air support and quickly two US Marine F-18 fighters and a Predator drone aircraft were above the fight ready to support. The TF reaction force of Bradley fighting vehicles and Abrams tanks proceeded toward the area.

Colonel Ferry could see the sheik’s men and AQI engaging on the video and he was able to talk to the sheik on the cell phone (through his translator). The F-18s were in position but the fighters were too closely engaged for the fast-attack aircraft to safely engage, so instead they made high-speed low-level passes and mock attack runs over the fight to let AQI know they were there in position and prepared to participate. The 1BCT was also in contact with the sheik, and they had his men wave towels and scarves so they could be identified on video. The AQI fighters, unnerved by the jets overhead, decided to break off the attack but as a final act of intimidation they tied the body of a tribal fighter to the bumper of their vehicle and dragged it behind their convoy of four vehicles as they loaded up and departed the Shark Fin. This was a mistake.

The cars dragging the body down the road were clearly visible to both the UAVs and the F-18s. As the cars left the neighborhood and they could be safely engaged they were attacked by the F-18s and the Predator-firing Hellfire missiles. Three of the four vehicles were destroyed. Other AQI fighters leaving the scene were intercepted by TF 1/9 who, using the night-vision devices on their vehicles, ambushed the fleeing AQI vehicles with tank and Bradley fire. By dawn the task force’s quick reaction force was linked up with Sheik Jassim’s fighters at the Shark Fin, the area was secure, and another sheik had joined the Awakening. Jassim’s forces lost seven fighters while over a dozen AQI fighters were killed. The Shark Fin, one of the most important AQI support areas in eastern Ramadi, quickly became another bastion of support for the coalition and the Awakening movement, and a source of police recruits.

The Shark Fin fight was typical of the synergistic effects of the aggressive 1BCT tactics and the Awakening movement. The BCT inspired the sheiks to resist AQI, and the resistance of the sheiks enabled the aggressive tactics of the 1BCT. By November 2006, the operations of the 1BCT were hitting their stride. The brigade had control of over 70 percent of Ramadi, more sheiks were joining the Awakening movement, and both the coalition high command and the Iraqi government were becoming aware of and supporting the effort to pacify Ramadi. Hard fighting remained however. In December TF 1/37 began pushing east into some of the last AQI strongholds to establish police stations in preparation for the growing operational Iraqi police force. When the operation ended in January 2007 they had killed 14 AQI fighters, captured 72, and most importantly, established three police stations. By the end of January 2007 over half the tribes, 450,000 of the citizens of Ramadi were part of the Awakening movement. Most of the rest of the sheiks had openly declared their neutrality and had ceased resisting 1BCT and its Iraqi army and police allies. Only a handful of tribes were still in the AQI camp and they were mostly located in east Ramadi.

By the beginning of February the results of the combined 1BCT operations and the Al-Anbar Awakening were clearly evident and decisive. As the “Ready First” brigade began planning the end of its 15-month deployment in Iraq there had been no losses to IED attacks in a month. Operations by 1BCT, supported by the enthusiastic and effective efforts of the Iraqi army, police, and local militias, resulted in a casualty exchange rate of 55 killed AQI fighters for each loss to the 1BCT.

On February 18, 2007, the 1BCT, of the 1st Armored Division, relinquished control of Area of Operation Topeka, and prepared to redeploy from Iraq to its home bases in Germany. The 1BCT of the 3rd Infantry Division from Fort Stewart, Georgia took over the battle. When the “Ready First” left Ramadi the battle was not over, but the end was in sight. Large portions of the city were completely clear of AQI influence and openly supportive of coalition forces. Soldiers could walk the streets without their combat equipment. The 3rd Infantry Division continued the fi“ht, building on the strong relations and the tactics established by the Ready First.” The coalition forces took additional losses, had more sharp firelights, but by the summer of 2007 the city was not only secured, but was one of the safest large metropolitan areas in Iraq. AQI gave up its plans for Al-Anbar to be the center of an Iraq caliphate and retreated to safer areas outside of the province.

The battle for Ramadi was not a quick or an easy victory. The 1BCT lost 83 soldiers killed and hundreds wounded during the battle. Equipment losses were also heavy: Task Force 1/37 alone lost a total of 25 tanks, infantry fighting vehicles and trucks during the battle. Iraqi army and police forces suffered similar casualties, but AQFs losses were many multiples more. The 1BCT estimated that in nine months of operations in the city approximately 1,500 AQI fighters were killed and another 1,500 were captured.

The Ramadi battle demonstrated the tactical and operational approach necessary to achieve success in the urban counterinsurgency environment in Iraq. The approach required three key elements. First, it required aggressive offensive action to clear insurgents from a selected neighborhood and to establish a permanent military presence in the midst of the urban civilian population. Second, it required that a competent and capable Iraqi army and police force be able to hold that area against insurgent counterattacks after it was initially cleared. Finally, it required a combined coalition and Iraq effort to build a working urban infrastructure in the cleared area to win and maintain the loyalty of the civil population by demonstrating the clear benefits of peace, stability, and the rule of law under the government of Iraq.

The battle of Ramadi also validated many of the fundamentals of urban combat proven in previous urban warfare experiences. Huge numbers of infantry were not required for the fight. However, well-trained infantry targeted very precisely at specific objectives linked logically to a comprehensive plan were important. Snipers and special operations forces were disproportionally important to the success of the battle. Those specialized forces, however, could not operate independently but had to be tied closely to the operations and objectives of the larger conventional force. Armor and mechanized infantry made important and vital contributions to the battle and gave the coalition forces multiple asymmetric advantages in all the firelights with AQI. Finally, the urban battle requires tactical patience if large-scale military and civilian casualties are to be avoided. The battle of Ramadi took a year to win. However, the city was not destroyed in the process, and given that the population of almost half a million people were present throughout the battle, civilian casualties were relatively light.

The approach of the 1BCT to operations in Ramadi was the three-step “clear, hold, build” tactical approach. But that three-step approach had two major lines of effort which supported each other. One was the security and combat operations conducted by the 1BCT and its allies. The other, equally important, was the political engagement of the population through the civilian leadership, the sheiks, which the military leadership actively pursued. These two lines of effort, one military and the other political, reinforced each other and led to the success. Without political engagement with the sheiks and the Awakening movement 1BCT’s tactical operations would likely have still been successful, but they would have been much more costly, time-consuming and ultimately would have resulted in a city that was pacified but not cooperative. Likewise, without the support of the coalition forces, the sheiks’ revolt against AQI would have been bloodier, taken longer, and probably would have resulted in an incomplete success.

The three-step, military-political, operational model clearly worked in Ramadi. It became the template for the tactical operations that characterized the surge of American forces into Iraq under General David Petraeus in 2007 and into 2008. The surge offensive applied the tactics and operational approach used in Ramadi to all of the major urban areas in Iraq including Baghdad. Ultimately, the Ramadi operational approach, combining aggressive military action and political engagement with the urban population, was successful throughout the country. It brought sufficient security on a large scale to enable coalition forces to turn all major security operations over to the Iraqi army and police forces. Ultimately the urban operations techniques pioneered in Ramadi facilitated the withdrawal of all coalition military forces from Iraq in 2011.