It is easy to graze 365 days a year. Almost any forage can handle it. The trick is to provide grazing forage 365 days a year that actually meets the needs of the animal 365 days a year. Days spent grazing your animals, rather than feeding them mechanically harvested feed, is a primary way to improve profit.

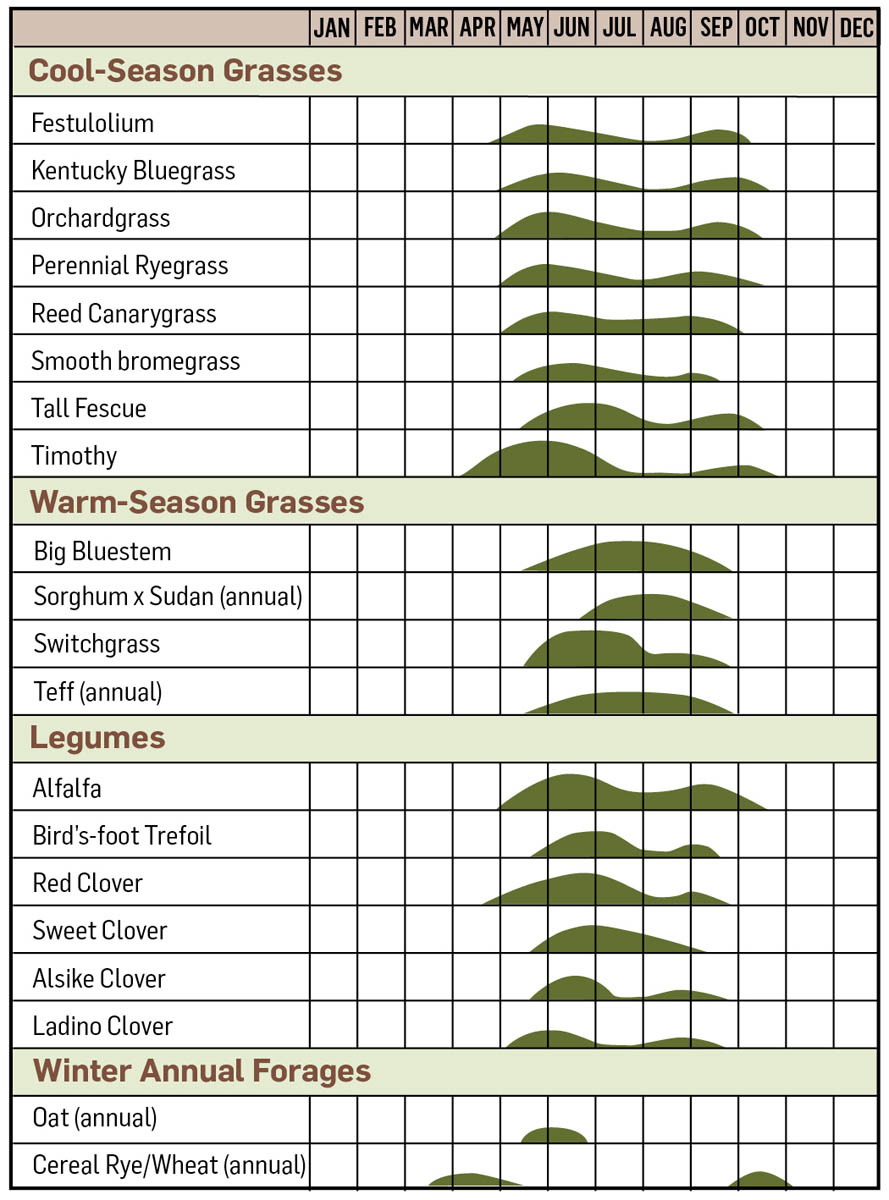

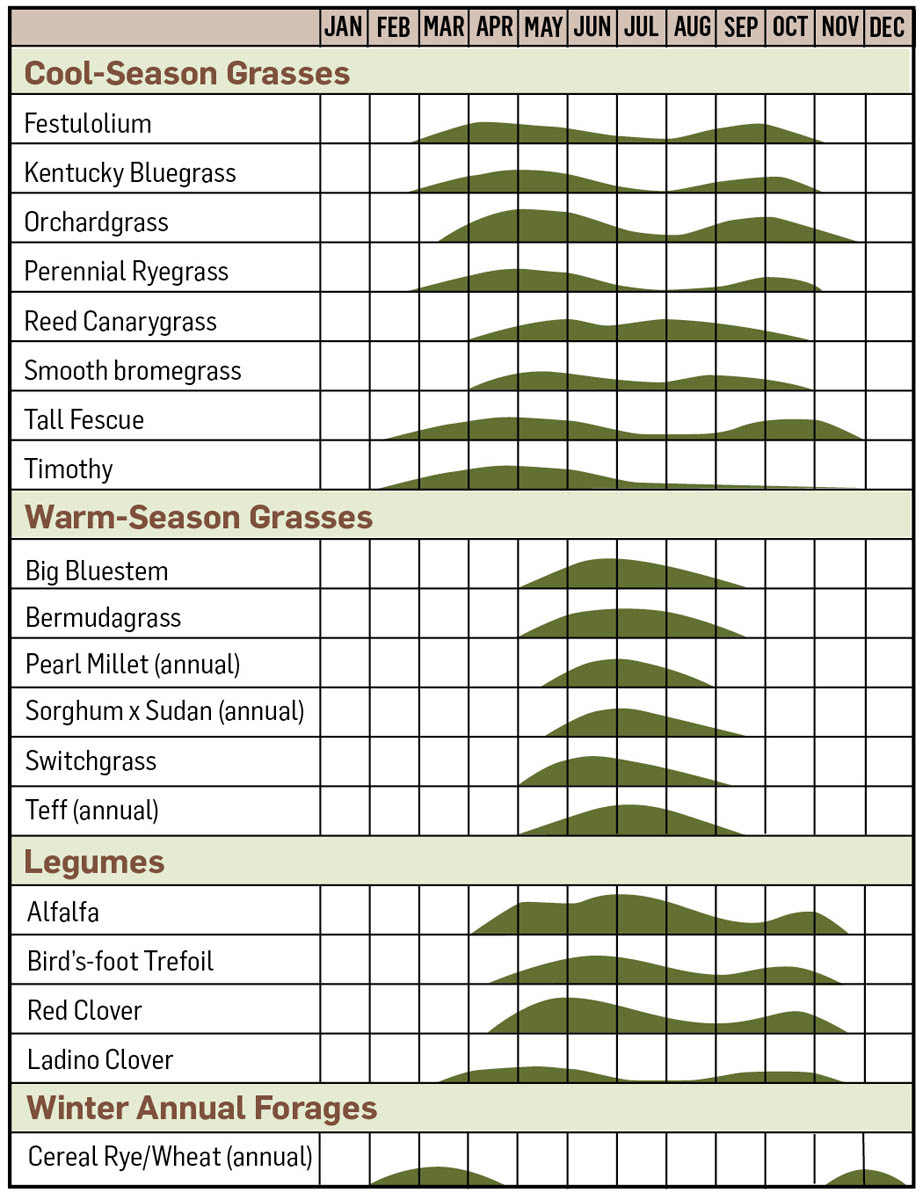

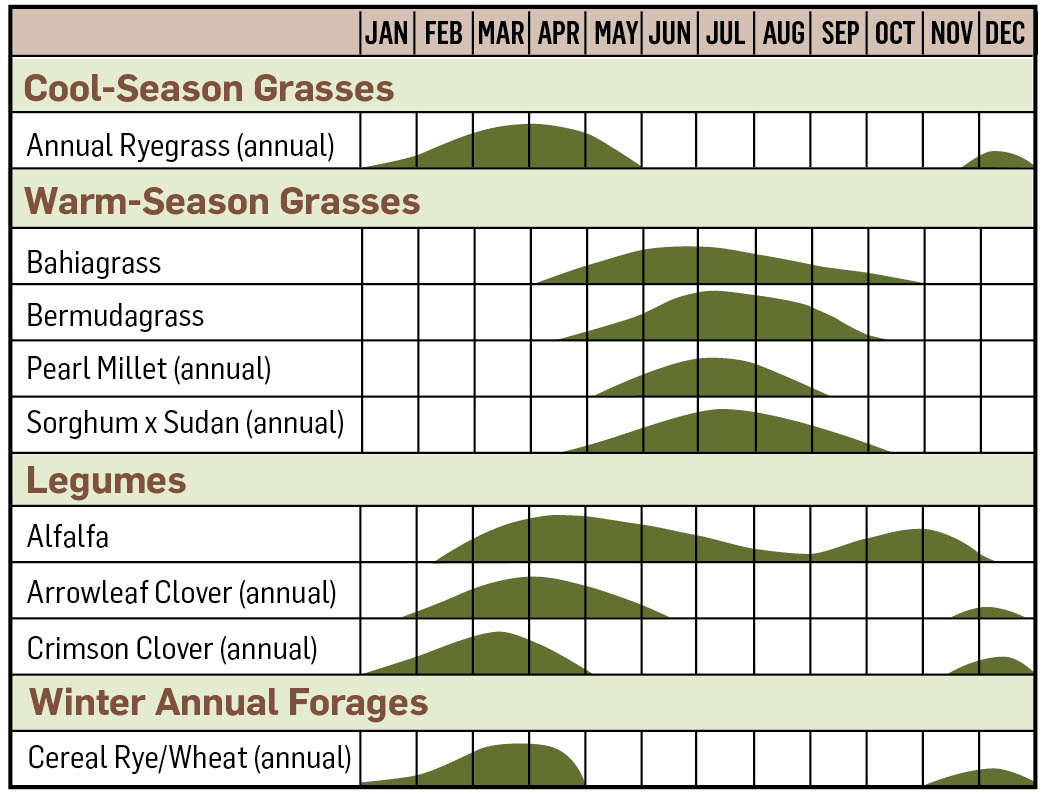

Different forages produce at different times of the year. Because it is usually prudent to have a sequence of vegetative forage in front of animals for as long a period as possible, it is important to track when different species of forages are growing in different regions. Opposite are growth curves for various species in different regions of the eastern United States. In the West, much of the variation in growth periods occurs due to elevation difference rather than latitude; it is difficult to chart the western states because there can be huge variations in timing of forage growth within just a few miles.

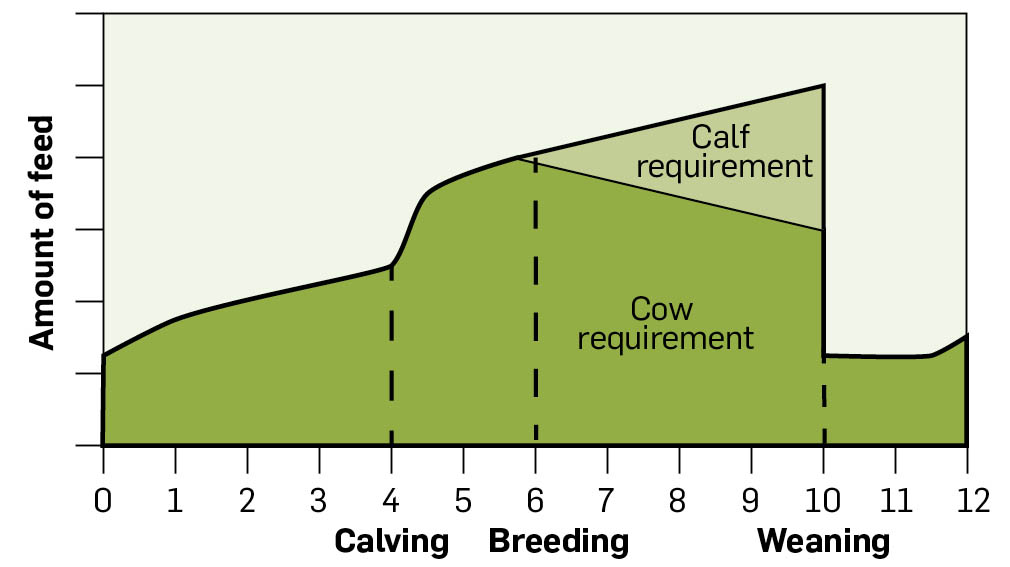

Beef cow year, with calving occurring on the first day of month 4 and weaning at 6 months of age, at the beginning of month 10.

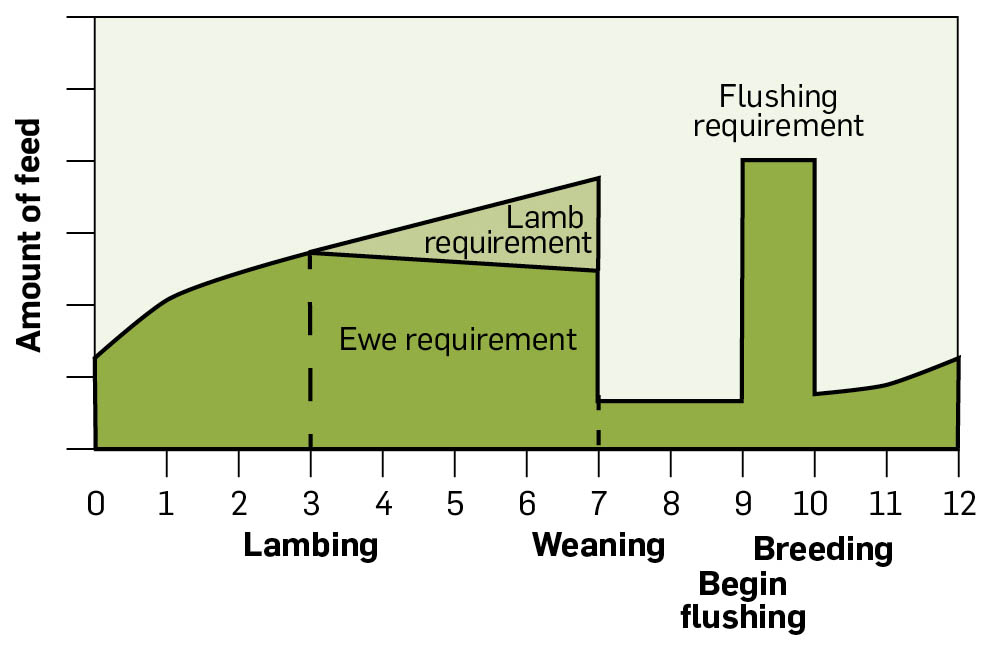

Ewe year, with lambing occurring at beginning of month 3 and weaning at 4 months of age, at the beginning of month 7.

Mechanically harvesting excess feed for later use is the usual practice for dealing with surpluses and shortages. In the extreme version of this (also the most common version), we harvest hay during the summer (when there is a surplus) and feed it in the winter (when there is a shortage). Years ago, this approach made sense because fuel was cheap, machinery was cheap, and labor was abundant. Those economic conditions no longer exist, and probably never will again. This approach definitely works, and it is one that almost every livestock operator is familiar with and comfortable with. But it probably isn’t the most profitable approach, so we will talk about other strategies as well.

Increasing and decreasing animal numbers to meet forage growth is another way to deal with surpluses and shortages. Simply put, it means obtaining more animals during times of surplus and disposing of animals during times of shortage. For example, in the Flint Hills of Kansas, it is common to go into Missouri and buy fall-born calves after they are weaned in spring and put them on native grass pasture to utilize the spring flush of high quality growth at that time, then remove them in mid-summer when the flush has been utilized.

Manipulating birthing and weaning dates. In my area, the hardest time of year to provide quality forage is January, February, and March. The highest-quality forage needs of a beef cow are right after calving. Guess when most people in my area choose to calve? That’s right, exactly when it is most difficult to supply high-quality feed.

Ideally, the beginning of the green season would be the beginning of the birthing season, and the end of the quality grazing season would be the weaning date. Doing otherwise almost always involves additional expense.

Upper Midwest and Northeast Zone

Northern Transition Zone

Coastal Zone

Southern Transition Zone

This does not always mean calving in May, as I do. For example:

I met a guy who had only 40 acres of native prairie for summer pasture for his cow herd. He was surrounded by irrigated corn used for producing hybrid seed. He rented the cornstalks and every year had radishes and turnips aerially seeded into the standing corn before harvest. He calved in the fall, which made sense for him because his peak forage supply was in the fall, and summer forage was his most limiting factor.

The point is to fit your lactation period to the period of high-quality forage. If you are not currently doing that, you can change your lactation period, change your forage supply, or spend a lot of money trying to make up deficiencies.

The fall growth of tall fescue can be accumulated and grazed later in the winter rather than feeding hay, a practice called stockpiling.

Supplemental feeding can help make up quality deficiencies in the base forage. Creep feeding (allowing the young, nursing livestock access to a feeder but excluding the adults) is one form of supplementing additional nutrients. In my area, where dried distillers’ grains are a cheap source of nutrition, a lot of producers use them to ensure adequate animal performance while herds are on inadequate pasture. My preference here is obviously to upgrade the forage, but since that is not always feasible, supplemental feeding beats letting animals become malnourished.

Supplements can also make much more efficient use of an otherwise useless feedstuff. In my area, warm-season native grasses are so low in protein during the winter that most people do not even bother to try utilizing it for pasture. With a little protein supplement, nonlactating beef cows do just fine. One pound daily of supplemental protein (4 pounds of dried distillers’ grains or 6 pounds of alfalfa hay per animal) is all it takes to give the rumen microbes enough nitrogen to utilize dormant native grass. This is very cheap compared to full-feeding hay, and there are literally tons of it available in my area for the asking in the winter, as long as the pasture was not overgrazed during the typical grazing season.

Confined feeding is a tool that most serious graziers look down on. Grazing snobs, I guess you could call them. I used to be one of them, but I have found confined feeding in some manner to be a valuable tool at times of forage shortage. It’s better than abusing pastures when it is obvious that animal demand is going to exceed forage supply.

I have used confined feeding for parts of the day (confine during a morning feeding and allow grazing in the evening feeding), or for a few days when the next paddock in the grazing rotation has not recovered sufficiently. Feeding hay just a few days during the growing season can save a lot of hay feeding later on, after pastures have been beaten up beyond recovery because we were “graze-100-percent-of-the-time” snobs. I believe grazing 100 percent of the time is a good goal to strive for, but I also think it is prudent to be prepared to keep animals off pasture for whatever reason.

Stockpiling forage for later use is a valuable tool. Simply grow forages during one season without livestock on the pasture and graze them the next season. The best example of this is using the summer and fall growth of tall fescue for winter grazing, but almost any forage can be stockpiled; some just keep their quality upon maturity better than others. Stockpiling forage is valuable not just for extending the grazing season; it is also a valuable tool for improving forage vigor. To have enough stockpiled forage that will be worth grazing requires resting forages long enough to accumulate some growth prior to dormancy, during which time the forage can restore vigor.

Allowing forage to go ungrazed during the growing season will require either more acreage or fewer animals, if the entire supply is eaten during the growing season under current management. Although it is tempting to graze as many animals as possible in an attempt to maximize income, it is usually more profitable to graze fewer animals (and feed no hay) than to graze more animals and be forced to feed hay for extended periods.

Accessing additional acreage has become one of my favorite options for providing quality grazing in fall and winter. The reality of the availability of solar energy is that we get more sunlight in spring and summer than we do in fall and winter. If we do a good job capturing sunlight and converting it into forage, we will always have more forage growth in spring and summer than in fall and winter, unless we somehow expand our acreage in fall and winter.

With the new interest in cover crops, there are many grain farmers who would like to reap the benefits of cover crops on their land but do not feel they bring the cash flow that grazing livestock does. This is your opportunity to rent their land after grain harvest and put grazing crops on them. Since most grain crops grow during the summer, this land is most often open in fall and winter. Seeding grazeable cover crops in wheat stubble, or in the residue of corn, soybean, or cotton, can provide a significant amount of off-season grazing. See the list below for suggestions of crops to grow at different times of the year.

Planting forages specifically to meet demands at certain times is useful if planting is done far enough in advance to provide forage during the deficit period. Therefore, this technique is most useful in meeting anticipated periods of shortage that occur every year.

Developing a forage chain allows planning for year-round grazing. (See “Seasonal Grazing,” opposite.)