There is a tranquil beauty in the sight of animals grazing. There is even a class of artworks called pastorals that depict such scenes, and these are innately, instinctively calming and serene.

Even more, the sight is intellectually stimulating, when you understand the miraculous transformation that takes place in the digestive systems of livestock — of tough, fibrous, inedible-to-humankind forage into meat and milk. There is a truly symbiotic relationship between the pasture and the beast: the beast obviously depends on the pasture, and the pasture also depends on the beast.

But there is also another symbiotic relationship that is not apparent to the casual observer, and that is the one between the host animals and the billions of microbes contained within them that actually do the heavy lifting of digesting pasture forages. Cellulose, the world’s most abundant organic compound and a primary component of forage, is completely indigestible by higher animals, including humans and grazing livestock. But it can be digested by a number of bacteria, and these bacteria happen to inhabit the digestive system of grazing livestock.

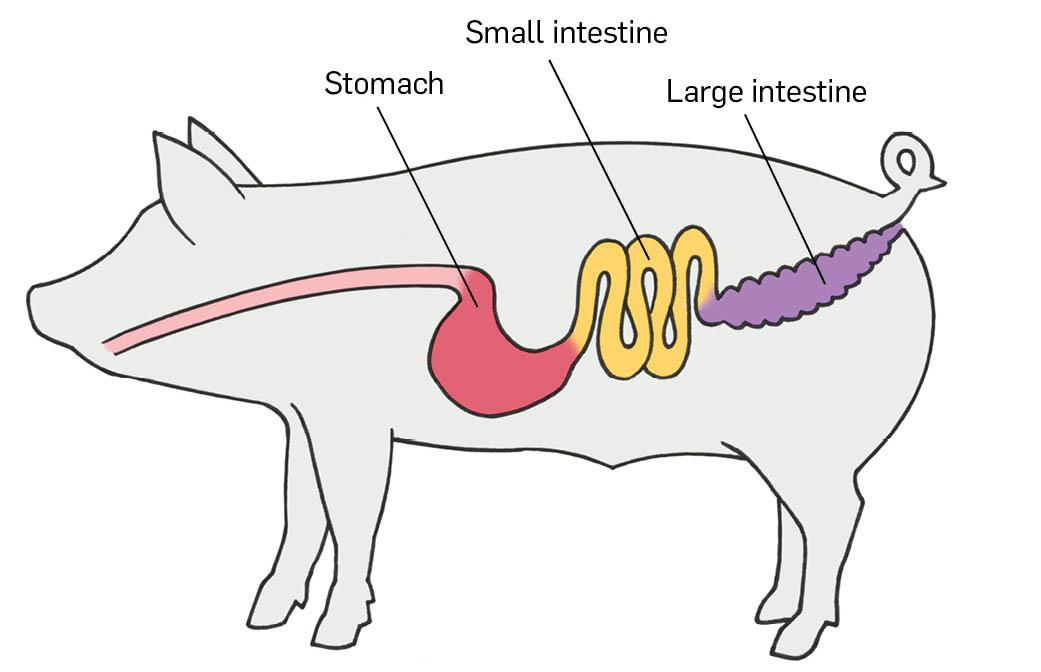

Monogastric animals, such as humans, swine, and poultry, have only a simple stomach and host comparatively few cellulose-digesting microbes in their digestive system. These species derive very little energy from forage, though they may get important vitamins and minerals. Forage can be a component of the diet, but it should not be the sole or primary component.

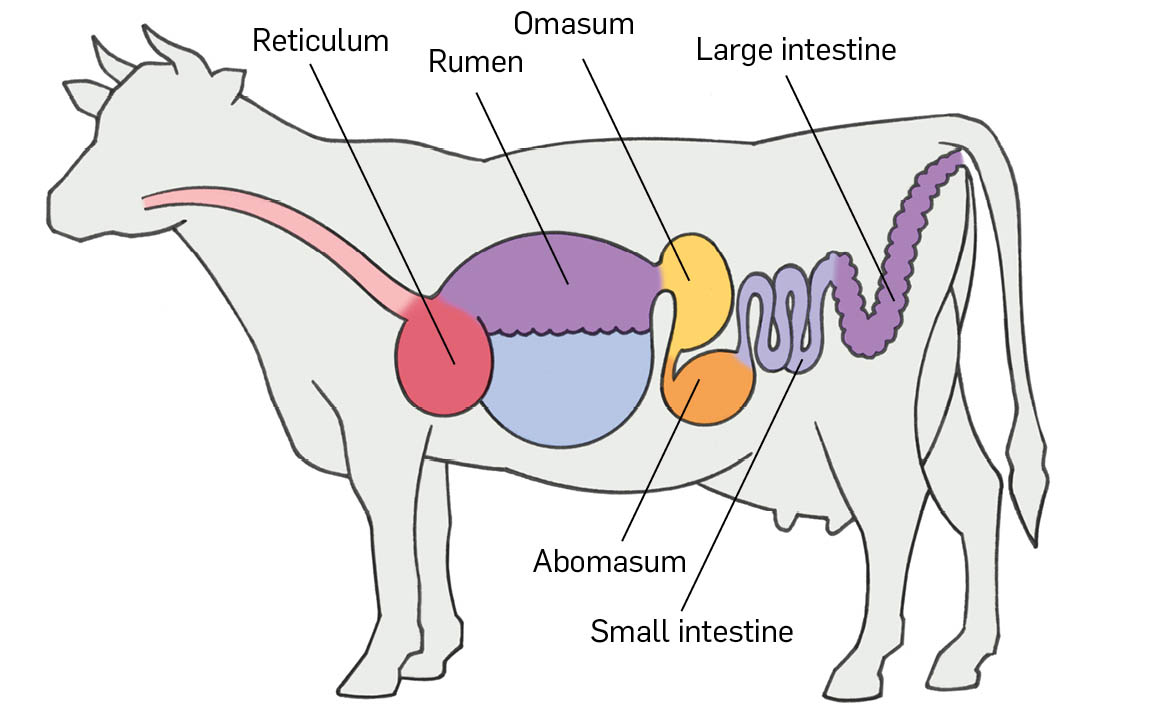

Ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats, on the other hand, have a four-chambered stomach. One of those chambers is the rumen, a huge (in cattle it may hold 55 gallons) fermentation vat where microbes can break down and utilize a whole host of feedstuffs that are completely useless to monogastrics. The bacteria and other microbes eat the forage, and the animal in fact digests the bacterial by-products and the bacteria themselves.

The microbes produce several products. One group is a set of organic acids (acetic, lactic, propionic) that the animal can use as a source of energy. Of these acids, the process that produces propionic acid is used most efficiently as an energy source, because it does not result in methane formation.

Methane, one of two gaseous products of the rumen, contains energy (it is the major component of “natural gas” and, obviously, burns). It is usually belched out of the rumen, which in chemical/ biological terms means a loss of potential energy for the animal. Some microbes can eat the methane, but it seldom sticks around long enough to be consumed. The other gaseous product of the rumen is carbon dioxide, which has no biologically available energy.

Ionophores, a form of mild antibiotic fed to ruminants, can shift the rumen population in favor of propionic acid–producing microbes and thus result in less methane production. Microbes also produce a polysaccharide slime that coats their bodies, and as the name suggests, it is a sugary substance that the animal can digest as a source of energy. The microbial bodies themselves are passed on to the rest of the digestive tract and are the source of amino acids (protein) for the animal.

The fermentation also produces almost if not all of the water-soluble vitamins needed by the animal, as well as vitamin K. Because fermentation in a ruminant occurs at the start of the digestive process, all the fermentation products are produced before food reaches the small intestine, where the most efficient nutrient absorption occurs. Intake in a ruminant animal is limited by the rate at which the forage is broken down by the microbes. The lower the forage quality, the slower the rate of passage, and thus the lower the intake.

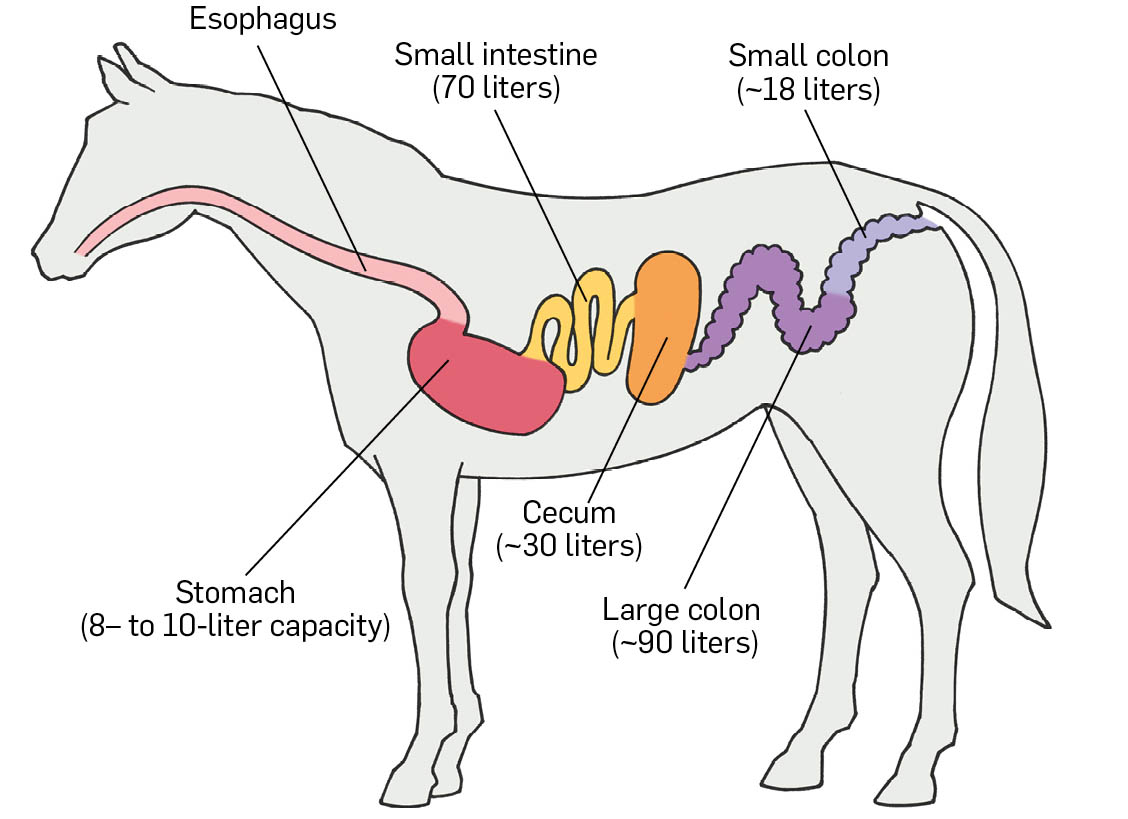

Cecal fermenters such as horses and rabbits are technically monogastrics, but for a fermentation chamber they have the cecum, a pouch between the small and large intestines. Cecal fermentation is similar to what occurs in the rumen, but since it occurs after food passes through the small intestine, the fermentation products must be absorbed by the less efficient large intestine.

This explains why horses have a reputation for being “hay burners”; they must eat more than a ruminant to have the same performance, because cecal fermentation is less efficient at getting nutrients into an animal than rumen fermentation. Rabbits compensate for this inefficiency by consuming their own “first run” feces to give a chance for the fermented material to be absorbed in the small intestine.

Comparing the Digestive Systems of Domestic Livestock

Monogastric digestive system

Cecal fermenter system

Ruminant digestive system

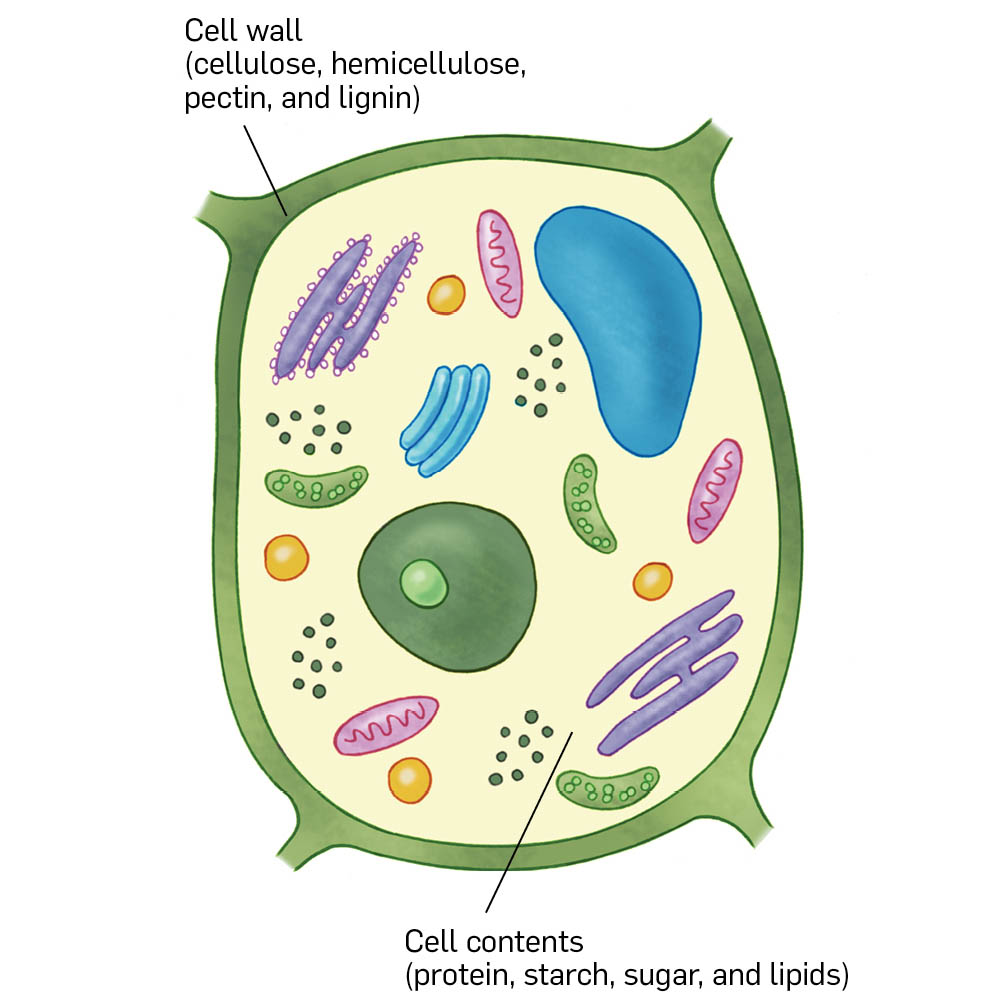

Geography of a Plant Cell

In contrast to ruminants, the feed intake of a cecal fermenter is not discouraged by poor-quality forage. Horses seem to be particularly able to compensate for poor-quality forage by eating more, which explains why they can survive in arid rangelands dominated by tough warm-season grasses that are dormant much of the year.

The vegetative material of plants consists primarily of plant cells, and these cells comprise two broad classes of materials with distinctly different nutritional characteristics: the cell contents and the cell walls.

The cell contents include chemical compounds — protein, lipids (fats and oils), starch, and sugar — all of which are essentially 100 percent digestible by the animal, if they are all accessible to the microbes. The problem is that the useful substances are encased by the cell wall, which resembles the wrapper on a candy bar. No matter how good the stuff inside is, it is only available if the wrapper is taken off.

Cell walls consist of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin. The first three compounds can be digested by the microbes in the rumen and cecum to some degree. That degree is determined by how much lignin is incorporated into the structure. Lignin is not digested to any appreciable degree by rumen microbes. In soil, lignin is broken down by fungi, and the fungi population of the rumen is pretty minimal compared to that of the other microbes.

Lignin is not only indigestible itself, but when it is intertwined with cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, they become indigestible as well. The degree to which nearly all plant material is digested by the microbes in a herbivore is dictated by the lignin content, and reducing lignin in plants is the key to improving animal performance — growth, milk production, wool production, whatever the target product.

Essentially the “wood” in a plant, lignin is a tough fiber that the plant uses for structural stability. Lignin content is higher in stems than in leaves; hence, leaves are much more digestible than stems. Similarly, lignin content increases with plant maturity, so less mature plants are more nutritious. This explains why animal performance is much higher on immature forage and when grazing pressure is low enough to allow animals to select a diet composed mostly of leaves with very few stems. As we saw in the previous chapter, this also allows optimal performance for the plants.

I will repeat the same chorus loud and clear throughout this book: proper grazing pressure benefits plant, animal, and profit. Overgrazing harms all the above.

Protein is highest in immature forage and declines rapidly in most plants with maturity, another reason immature forages tend to produce better gains in general than mature forages. Once a forage reaches a certain amount of protein content, however, there is no benefit to the animal from additional protein. This optimal level depends on the class of the animal, with younger animals and lactating females requiring more protein than nonlactating mature animals, but once a protein level exceeds 16 percent or so, any excess protein must be broken down into ammonia and carbohydrate to be used for energy. Excess ammonia can put a burden on the animal’s excretory system and can cause “gamey” flavors in meat, a result of diets with too much protein (usually in excess of 25 percent).

Ordinarily, protein sources are too expensive to feed in excess, but the abundant supply of cheap, high-protein distillers’ grains in ethanol-producing areas has led to some animals getting diets with excess protein, resulting in off-flavors. Grass finishing on pastures with too high a legume percentage can also cause these off-flavors.

Often, however, too little protein is a far bigger issue than too much. As protein drops below about 12 percent or so, animal performance declines. If there is less than 7 percent protein in a forage, the rumen microbes are unable to reproduce, and animal performance drops rapidly. Thus, if animals are forced to eat forage with protein levels below 7 percent, as is common in dormant warm-season grasses, they should receive some protein supplementation. Mature dry cows usually need a total of about 1 pound of actual protein per head per day. For more information on supplementation strategies for low-quality forage, see the discussion of warm-season native grasses in chapter 8.

Grasses tend to be higher in fiber and lower in protein than other plants, but the fiber of grasses is much more digestible than the fiber of legumes and forbs because it is comparatively low in lignin and high in cellulose. Grasses tend to be higher in sugar and energy content than legumes and forbs. Still, grass passes through the rumen more slowly than legumes and forbs because of the time it takes the fiber to digest, and animals can only fit so much grass into the rumen at a time.

Legumes have faster rates of passage, and the legume leaves take up very little room in the rumen, but they have a low energy content. Animals with access to both grasses and legumes will eat their fill of grass and still be able to fit some legume leaves in between the grasses; thus they will eat more and gain faster.

The leaves of woody plants tend to have very low lignin content because they have no need for structural strength, which is provided by the twigs and trunks of trees and shrubs. They do not lignify as the plant matures, the way herbaceous plants do. Thus, tree leaves are often very high in protein and digestibility compared to other plants, particularly in late summer. This explains why a diverse diet that contains grasses, legumes, forbs, and woody plants will result in the best animal performance, making the best use of the nutritional advantages of each forage type.

Monitoring animal performance after the fact is easy: they either performed, or they didn’t. They either weighed (or milked) as you hoped, or they didn’t. Unfortunately, by then it is too late to alter the fact. Monitor the animals to determine if they are eating enough and if they are digesting what they are eating.

A good way to monitor intake on a ruminant is to look at the left flank, where the rumen protrudes (or should be protruding). If animal intake is adequate, the rumen should bulge out. If intake of either feed or water is limited, the body contour will seem sunken there.

Monitoring digestibility is also easy. Just look at the manure (this is a better clue for cattle than it is for sheep or goats). Cattle on good-quality pasture will produce flat and runny cow pies. Poor-quality feed will result in thick cow pies. If forage quality is inadequate for the desired performance, it may be necessary to alter grazing management to leave more residual, or allow a larger allocation, or move to a more vegetative forage. If none of these options are viable, the choice may be to provide supplements or to reduce animal numbers to allow the remaining livestock a wider choice of forage.

Animals consuming poor-quality feed will produce thick cow pies.