Section 1

Introduction to the Study of Missions

Chapter 1

An Overview of Missiology

Justice Anderson

This chapter introduces readers to the fascinating field of missiology. Missiology, a technical discipline within theological education, is relatively new in comparison to other classical disciplines. In fact, missiology only slowly has won its way into the theological curriculum. Until recently, many classical theologians considered missiology a second-class study. Few, except the experts in missions themselves, had considered missions study seriously as a necessary part of the theological encyclopedia. Starting around 1867, formal professorships of missions were inaugurated in Germany, Scotland, and the United States. In spite of this acceptance, the study of missions has remained marginal and only grudgingly accepted by many.

The Term Missiology

With acceptance of the discipline, an increasing need also arose for a term to describe and designate the study. Contemporary missions literature has accepted the term missiology. An understanding of this term provides a more adequate understanding of the field of scientific missions study.

Although the Scots and Germans initiated the formal study of missions, the word missiology came into the English language from the French word missiologie. The acceptance of the transliterated term missiology in English has not, however, come either rapidly or easily. On the contrary, many theologians express a positive dislike of this term, which they consider a horrid, hybrid word! These critics maintain the word—a compound of Latin and Greek—represents a clumsy construct (Neill 1970, 149). They feel that these two words, one Greek and another Latin, is a linguistic monstrosity!

One notes that such “monsters” occur rather frequently. For example, sociology, terminology, numerology, methodology, scientology, and even theology are commonplace. Most scholars believe, therefore, that good reasons exist to retain missiology as the English terminus technicus for the science of missions (Myklebust 1955, 28–29).

In the opinion of this writer, it is the theological content of the etymology that excites enthusiasm. The Latin word missio and the Greek word logos constitute the compound word, but the original architects of the word—Graul, Warneck, Duff, Bavinck, Kuyper, Plath, Myklebust, Verkuyl, et al.—had much more in mind. These outstanding theological professors in Europe and America emphasized the study of missions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They saw it as a theological discipline but differed about how to incorporate it into the curriculum. David Bosch and Olav Myklebust describe in detail this development (Bosch 1991, 489ff and Myklebust 1955).

For these writers, missions meant the expansion of Christianity among non-Christians, that is, among people not baptized with Christian baptism. More precisely, these writers considered missions the conscious efforts on the part of the church, in its corporate capacity, or through voluntary agencies, to proclaim the gospel (with all this implies) among peoples and in regions where it is still unknown or only inadequately known. Missions is, they believed, not only a department of the church but the church itself in its complete expression, that is, in its identification of itself with the world (Myklebust 1955, 27).

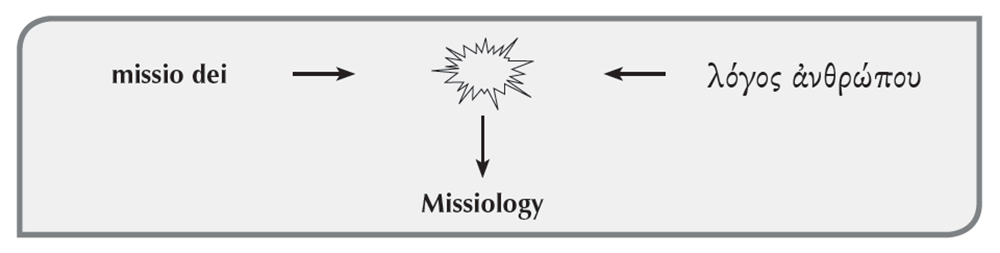

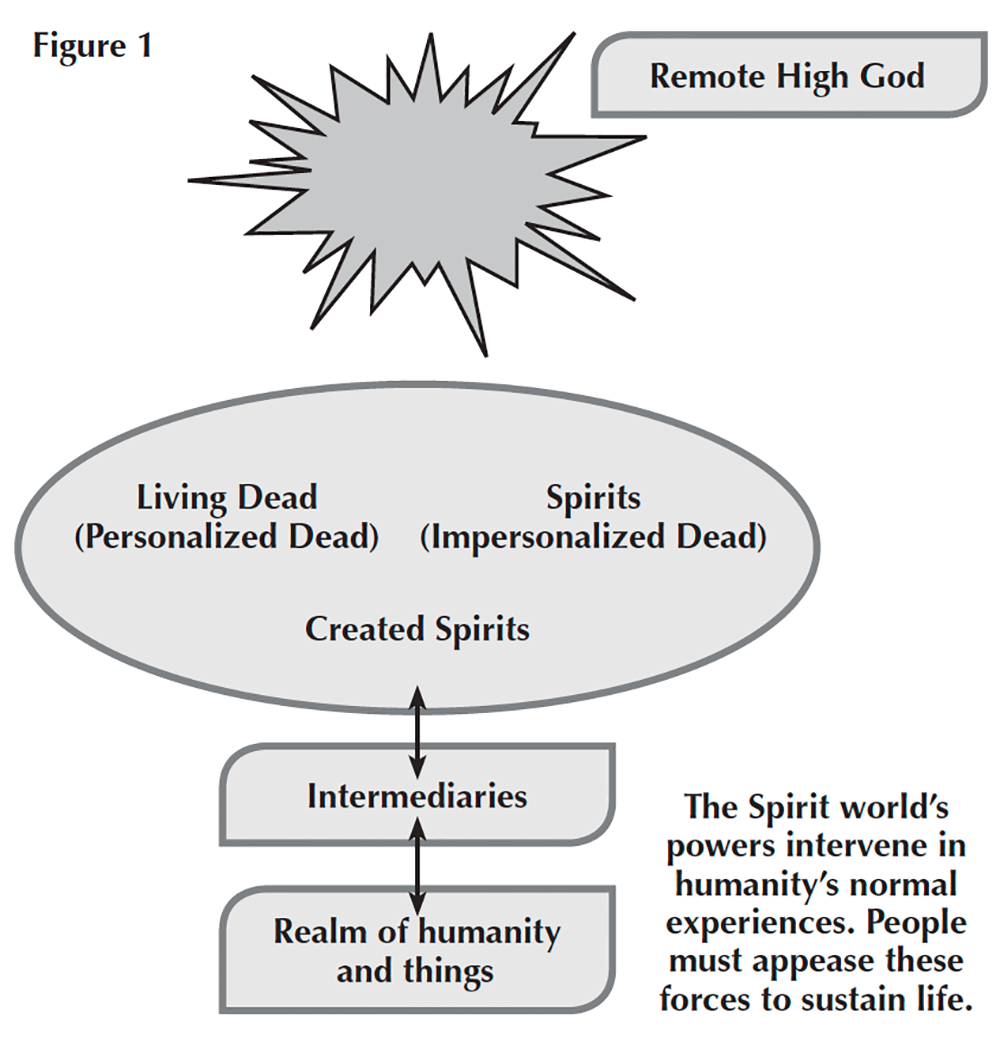

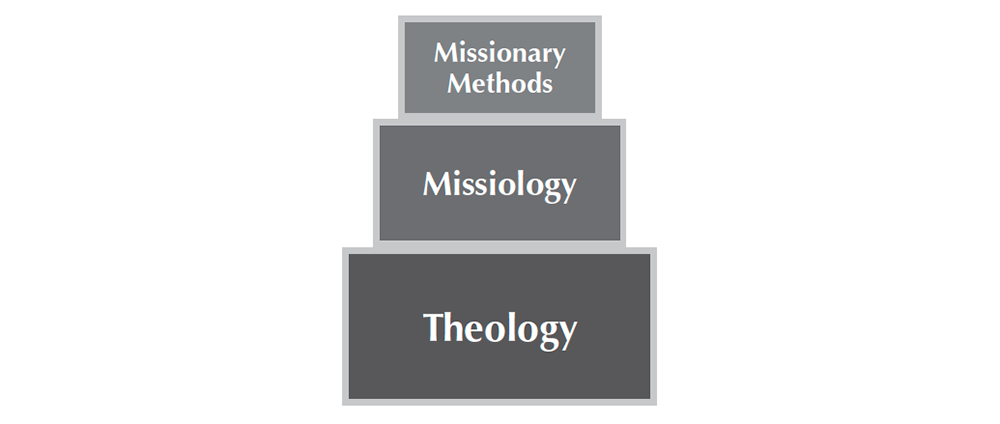

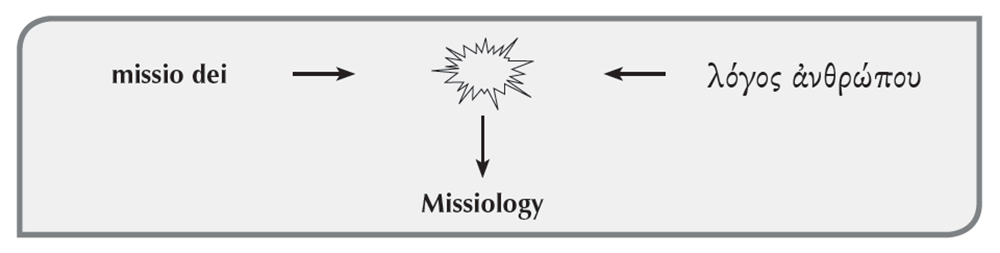

Seen in another light, the term missiology includes the Latin missio referring to the missio Dei, the mission of God, and the Greek word λόγος (referring to the λόγος ἀνθρώπου, the nature of mankind). The word missiology, therefore, connotes what happens when the mission of God comes into holy collision with the nature of man. It describes the dynamic result of a fusion of God’s mission with man’s nature. It is what occurs when redeemed mankind becomes the agent of God’s mission, when God’s mission becomes the task of God’s elected people. We can picture the field of missiology with the following graphic:

Stated still another way, the word carries theological weight; it throbs with theological meaning! It envisions man caught up in God’s redemptive current! It says that God has a divine purpose for all peoples that he is carrying out through his redeemed people—that it is his mission. It points out why, when, and how God and man cooperate in redemptive activity. Missiology, etymologically speaking, is the study of this redemptive relationship, of what has happened and is happening when the church’s missions are at the service of God’s mission. Its theme must be the way of God among the peoples of the earth—a story that begins with the call of Abraham to be the father of a chosen people and that will continue until the second coming of Christ and the end of the age (Neill 1970, 153). The term contains all of this meaning.

Alternative Terms for Missiology

The quest for an appropriate term to describe this science of missions produced an evolution of interesting alternatives in several languages. Gustav Warneck, the nineteenth-century European pioneer of the science of missions, suggested the term Missionslehre, theory of missions. Abraham Kuyper, the eminent Dutch theologian, suggested several terms, none of which caught on. He said apostolics expresses the notion of missions in general; but because it might be confused with the “apostolate,” an office that no longer exists, he and others deemed it inappropriate and possibly confusing.

Next he coined prosthetics, “to add to the community”; later auxanics, “to multiply and spread out”; still later he borrowed from another halieutics, “to fish for men”; and finally elenctics, which ascertains a view of non-Christian religions. He felt that missionary science must be able to evaluate other religions properly and biblically. Kuyper’s terms were short lived and gradually faded away. Missiology in different forms and languages slowly came into vogue (Verkuyl 1978, 2).

The term missiology is of rather old vintage, especially in Roman Catholic use. It springs from the Latin translations of the Greek verb apostellein, in Latin, mittere, missio, missiones. These derivations surfaced in the great Roman Catholic missionary expansion of the sixteenth century led by the Jesuits (Verkuyl 1978, 2) but were practically unknown among Protestants. Since World War II, missiology and its transliterations in other languages have slowly won acceptance as the official names of the missionary science.

Johannes Verkuyl, the noted Dutch professor, after a long discussion of all the other exceptions, opted for the term “for the sake of clarity and to broaden the uniform use of language” (Verkuyl 1978, 2). Olav Myklebust, the Norwegian scholar, in his meticulous discussion of the matter, felt that good reasons enjoined adopting “missiology” as the technical term for this branch of theological learning (1955, 28–29). These writers were joined by the majority of German, North American, British, French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese missiologists, who have adopted adaptations of the term in their respective languages. It is the common term used by Two-Thirds World theologians as they slowly produce their missiology.

The Theological Evolution of Missiology

Theology is a living organism rather than a hodgepodge of separate studies. Its subdivisions, such as apologetics or missiology, cannot, and should not, be radically separated. Nevertheless, every reason remains to accept the science of missions as an independent entity. It has become an essential element in the theological curriculum. Godfrey Phillips points out the close relationship between Christian missions and Christian theology. Originating in the same religious experience, he writes, the two “are likely to flourish or fail together; weakening in theology is likely to be accompanied by weakening in missionary effort” (Myklebust 1955, 14). Missiology must continue to develop its theological relationship with the other disciplines in order to maintain its hard-earned place in theological education.

Not only has theology a duty to perform for missions, but it has much to learn from missions. In the early stages of the church, missions was more than a function; it was a fundamental expression of the life of the church. The beginnings of missionary theology are also the beginnings of Christian theology as such. This is why Martin Kähler, almost a century ago, said that “mission is the mother of theology” (Bosch 1991, 16). It is what Emil Brunner meant when he said later, “The Church exists by mission, just as fire exists by burning. Where there is no mission, there is no Church; and where there is neither Church nor mission, there is no faith” (i.e., no theology!) (Myklebust 1955, 27). Once again Godfrey Phillips, an Anglican divine, summed up the matter with these words:

The Church which is most sure of its own faith is best fitted to propagate it in the world. And gradually the converse of this is coming to light, namely the reflex action of missions upon the faith and the theology of the Church. Missions may from one point of view be regarded as a gigantic experiment to disprove or verify the classical doctrine of the divine-human person and the work of Christ. For two centuries, Protestant missions have experimented with bringing the news of one particular Saviour to men and women of amazingly different types . . . Two things stand out in the reactions: first the strange way in which each type finds Jesus as its kin . . . and second the way each type finds in Him the remedy for its special needs as well as for those common to all mankind. (Phillips 1939, 54)

These truths powerfully confirm the church’s sense of Christ’s significance as Son of Man and Son of God and stir up boldness for his deity and his saving efficacy. In short, the missionary endeavors of the church have helped theology to a fuller understanding of its task by providing a much-needed corrective and a wider perspective for its thinking. Missiology and theology must be “conjoined twins” in the theological curriculum; they are mutually interdependent.

The student of missiology must be cognizant of the historical development of this interdependency if he is to incorporate missiology properly into the theological curriculum and understand its relation to the other disciplines. A brief review of this development is relevant at this point.

In premodern times, theology was understood in two ways. First, it was concerned with everything related to God and man’s knowledge of God. This was the personal knowledge of God as experienced by the human soul. Second, it was the term for a discipline, a self-conscious, scholarly enterprise. Theologians long taught the holistic concept of theology; that is, they conceived the study as one, undivided discipline. Under the influence of the Enlightenment, a separation took place that produced theology as theory and practice. From this concept, theology gradually evolved into a fourfold pattern: the disciplines of Bible (text), church history (history), systematic theology (truth), and practical theology (application). From the influence of Schleiermacher and others, this pattern became firmly established and continues to this day (Bosch 1991, 490).

The so-called practical theology became principally “ecclesiology” and formed the basis of Christendom. Practical theology served to keep the church going, while the other disciplines were examples of pure, or classical, science. Theology, in this period, held largely an unmissionary posture because missions was assigned to the practical area that existed to serve the institutional church. Even after the revival of missions in the Roman Catholic Church, Protestant theology remained parochial and domesticated.

This unhealthy separation began to weaken because of the burgeoning Moravian antecedents and the William Carey-pioneered modern missionary movement. The new missionary spirit forced European theologians to incorporate the missions motif in the theological curriculum. Schleiermacher led the way by appending missiology to practical theology on the periphery of the theological spectrum (Myklebust 1955, 84ff). However, the fourfold division pattern remained sacrosanct.

In the mid-nineteenth century, missiology tried another method to validate its standing within theology by declaring autonomy. Missiologists demanded the right to be a discipline apart. This demand brought down the ire of the “fourfolders”; but Charles Breckenridge at Princeton in 1836, Alexander Duff at Edinburgh in 1867, and Gustav Warneck at Halle in 1897 founded chairs of missions at their respective institutions. Because of the intellectual respectability of these leaders, they won the right to teach missiology as a separate discipline (Bosch 1991, 491). The Roman Catholics founded the first chair of missions at a Catholic institution, the University of Munster, occupied by Josef Schmidlin, in 1910. This chair sprang largely from the influence of Warneck (Bosch 1991, 491).

This declaration of independence on the part of missiology was not all positive, theologically speaking. Many of the theologians did not accept these chairs as true professorships of theology. Missiology remained peripheral, the creature of the missionary societies and, in reality, became the institution’s department of foreign affairs! The theoretical disciplines remained aloof and accepted the new discipline with condescension, especially when the chairs were occupied by retired missionaries who had worked in “Tahiti, Teheran, or Timbuktu!!” (Bosch 1991, 492).

As an independent discipline in theology, missiology further distanced itself from the theoretical disciplines by falling into its own fourfold pattern. “Missionary foundations” paralleled the biblical subjects, “missions theory” paralleled systematic theology, “missions history” found its counterpart in church history, and “missionary practice” reflected practical theology (Bosch 1991, 492). This arrangement isolated missiology even more and made it a science of the missionary and for the missionary. British missiologists rebelled against this isolation and recommended that missiology be added as a unit to the other theoretical disciplines. This attempted integration concept never really worked and marginalized missiology even more.

None of the three models—incorporation, independence, or integration—resulting from this evolution satisfied the theological academy. Integration is theoretically and theologically the soundest, but today the independent model prevails in most theological institutions. However, since the 1960s, the church has gradually come to the position that missions can no longer be peripheral to its life and being. Missions has become no longer merely an activity of the church but an expression of the very being of the church. Bosch calls it the movement from “a theology of mission to a missionary theology” and considers it an element in his emerging ecumenical missionary paradigm (Bosch 1991, 492).

This recovery of the mission of the church has impacted missiology. An amalgam of the fourfold theology with the fourfold missiology is in formation. Missiology has its dimensional aspect in which it permeates all theological disciplines and is no longer one sector of the theological encyclopedia, but it also has its intentional aspect in which it addresses the global context. From this new point of view, missiology has the twofold task of relating to theology and praxis at the same time. It must constantly challenge theology to be a “theology of the road”; but at the same time, it must exercise theology in context.

J. M. van Engelen sums up this responsibility best when he says that the challenge of missiology is “to link the always-relevant Jesus event of twenty centuries ago to the future of the promised reign of God for the sake of meaningful initiatives in the present” (Bosch 1991, 498). Today, missiology, while maintaining its departmental identity, is seeking help from, and offering help to, the classical theological disciplines. It is a pilgrim discipline in constant exodus. As Bosch observes, “missiologa semper reformanda est.” Only in this way can missiology become not only ancilla theologiae, the “handmaiden of theology,” but also ancilla Dei mundi, “handmaiden of God’s world” (Scherer 1971, 153).

The Definition of Missiology

Having treated at length the etymology and theology of the term missiology, it is now necessary to formally define it. A brief perusal of some classical definitions of the term helps:

Abraham Kuyper: “The investigation of the most profitable God-ordained methods leading to the conversion of those outside of Christ” (Bavinck 1960, xix).

Olav Myklebust: “The scholarly treatment, from the point of view of both history and theory, of the expansion of Christianity among non-Christians” (Myklebust 1955, 29).

Johannes Verkuyl: “Missiology is the study of the salvation activities of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit throughout the world geared toward bringing the kingdom of God into existence” (Verkuyl 1978, 5).

Alan Tippett: “The academic discipline or science which researches, records and applies data relating to the biblical origin, the history (including the use of documentary materials), the anthropological principles and techniques and the theological base of the Christian mission. The theory, methodology and data bank are particularly directed towards: (1) the processes by which the Christian message is communicated; (2) the encounters brought about by its proclamation to non-Christians; (3) the planting of the Church and organization of congregations, the incorporation of converts into those congregations, and the growth and relevance of their structures and fellowship, internally to maturity, externally in outreach, as the Body of Christ in local situations and beyond, in a variety of culture patterns” (Tippett 1987, xiii).

Ivan Illich: “The science about the Word of God as the Church in her becoming; the Word as the Church in her borderline situations; . . . Missiology studies the growth of the Church into new peoples, the birth of the Church beyond its social boundaries; beyond the linguistic barriers within which she feels at home; beyond the poetic images in which she taught her children . . . Missiology therefore is the study of the Church as surprise” (Bosch 1991, 493).

The analysis of these definitions, long and short, common and exotic, reveals missiology as a discipline in its own right but an essentially dynamic discipline. In other words, it has a symbiotic relation to the entire theological curriculum. It depends heavily on theology, history, and the practical disciplines; but it also must dip into the behavioral sciences, namely anthropology, sociology, psychology, and linguistics. It is not a mere borrower from other fields, for these dimensions are related to each other in dynamic symbiosis. They interact, influence, and modify one another.

Missiology cannot be static; it grows; it adapts; it relates to the ever-changing world. It is never complete. However, in every new situation it must also retain its own internal integration. For that reason, the simplest definition of missiology is “the study of individuals being brought to God in history” (Tippett 1987, xiii). But for the purpose of integrating its components, the following definition will serve to finalize this section:

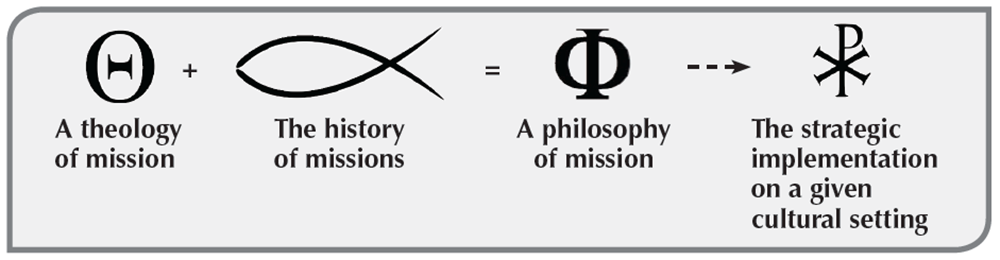

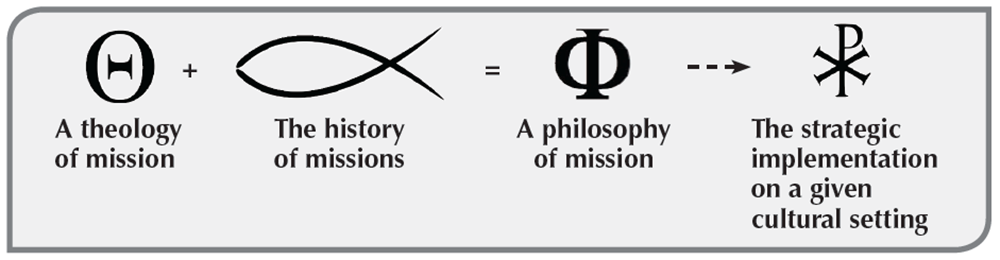

Missiology is the science of missions. It includes the formal study of the theology of mission, the history of missions, the concomitant philosophies of mission and their strategic implementation in given cultural settings.

The Scope of Missiology

The foregoing definition of missiology demonstrates the remarkable scope of the discipline. The scope of missiology can best be expressed by a simple formula suggested to this writer by the outline of William Carey’s Enquiry. Using Greek and early Christian symbols it would result in the following formula:

Most evangelical seminaries have departments of missions that continue to follow a fourfold pattern of missiology mentioned above. However, approximation to the classical disciplines on the part of the contemporary missiologists is leading to a greater integration of the missionary motif in the curriculum. At the same time, the more theoretical departments are realizing their need of missiological orientation. Although most faculties employ missions professors who have had field experience, they also require solid academic credentials and expect their missions department to do more than only recruit candidates and support the denominational program. They want men and women who can reflect theologically on their pragmatic experience. With this in mind, an examination of the units of study mentioned in the formula is in order.

Theology of Mission

Academic missiology must be seen vis-à-vis systematic theology. The starting point of all missiological study should be missionary theology. The dynamic relationship between systematic theology and academic missiology has already been discussed. They are mutually interdependent. The missionary enterprise needs its theological undergirding; systematic theology needs missionary validation. Missions is systematic theology in action, with overalls on, out in the cultures of the world! The missionary is the outrider of systematic theology. The greatest proof of the validity of theology is the success of the missionary movement. Perhaps this should be dramatized by asking the missionaries to be appointed in academic regalia and the theologians to march to convocation in pith helmets and bermuda shorts! The presence of a missions department in the seminary should be a reminder of the missionary motif that should permeate all theological departments.

The world of missiology is experiencing a return to theological reflection. A quest for the essence of the faith is in progress. With their wealth of cross-cultural experience, missionaries and nationals are seeking the “contextualization” of the gospel in their respective cultural settings. The modem missionary movement, launched from a firm theological pad, tended to drift into benevolent humanism in its second and third generations. However, recent evangelical missiological pronouncements such as the Wheaton and Berlin Declarations of 1966, the Frankfort Declaration of 1970, and the Lausanne Confessions of 1974 and 1989, indicate a return to a solid confessional basis. Together with the biblical revival in the ancient Christian traditions such as the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox churches, this fusion of missiology and theology is encouraging.

Another indication of this trend is that the Two-Thirds World churches are producing their first real theologians. They insist on a theology of praxis, on “doing theology.” The rise and fall of the liberation theologies in Latin America is a case in point. In spite of all its fallacies, liberation theology was an honest attempt to reflect on orthopraxy, or, in other words, to find out how theological orthodoxy could become efficacious in oppressive cultures.

If this trend toward indigenous theology can avoid the error of becoming so syncretistic and nationalistic that it ceases to be Christian, some exciting new theologies of mission will result. Missiology in the seminaries must prepare the cross-cultural missionaries to deal with this trend. Missiology and theology must continue to spend time together in the academy.

A second consideration in a theology of Mission relates to the missionary nature of God. The Christian mission is essentially God’s mission. Here we make a distinction between the words mission and missions. In missiological usage, the singular Mission (usually upper case) refers to the missio Dei, the mission of God. The plural missions (usually lower case) refers to the missions of humans. In other words, the “mission of God” makes necessary and undergirds the “missions of humans.” The redemptive activity of God recorded in the Bible sets the pattern.

The incarnate God in Christ is the key. God’s called-out, redemptive community, the church, is to be on mission. The nature of God and his church make the “missions” of the churches necessary. P. T. Forsyth expresses it in similar fashion, “The missionless church betrays that it is a crossless church, and it becomes a faithless church” (Myklebust 1957, 316).

A third concept in a theology of Mission is the missionary nature of the Bible. Generally the special revelation forms the biblical basis of missions. The Bible is the record of the missionary activity of God. Could this missionary motif not be the key to its unity and wholeness? It is the key to that puzzling interplay between the particular and the universal found in the Bible. Many are bogged down in the particulars and the prooftexts of the Bible, which lead to division and provincialism. The missionary motif brings a refreshing unity and universality to Bible study that a reactionary constituency desperately needs.

For instance, could we not show that the particular covenant of God with Abraham in Genesis 12 was God’s strategy to fulfill his universal covenant with Noah in Genesis 9? (Sundkler 1965, 11–17). The particular callings and actions of God with Abraham, Israel, the remnant, and the New Testament church must be seen in the light of the universal sovereignty and redemptive purpose of God. The doctrine of election will be better understood when seen as election for mission and not for privilege. The Old and New Testaments can be tied together by showing the missionary implications of a contrast between Babel and Pentecost (Sundkler 1965, 11–14), or how Jesus was careful to move from the particular to the universal in his own earthly ministry.

In the New Testament we have let Paul dominate the missionary picture. What about the missionary implications of Jesus’ teachings in Mark 13 or of the missionary lesson of the “cleansing of the temple”? It is the overarching theology of mission contained in the Bible that makes it a unity. From Genesis to Revelation we see a double line of salvation based on the principles of election and substitution—a minority is elected to bear blessings to the majority. The idea of “the people of God” chosen to be a missionary community “to all peoples” is the Bible’s central theme.

A fourth factor in the theology of Mission includes the missionary nature of the church. Many evangelicals, committed to the local church polity and to the planting of churches on their mission fields, are in danger of falling into provincialism and ethnocentrism. They need a dose of the New Testament doctrine of the universal church, the spiritual community of Christ in the world. The local congregations will be spiritually enhanced and doctrinally undergirded when viewed from the perspective of the universal church and its relation to the kingdom of God. Church growth will not be an end in itself but a means to the end of world evangelization. The relation between the kingdom, the church, and the churches is a theme for missions and needs more emphasis in a correct theology of mission.

A fifth truth in the theology of Mission involves the missionary nature of the Christian ministry. A correct interpretation of the New Testament doctrine of the ministry is essential for good missiology. The official ministers mentioned in Ephesians 4:11–12 are not to do all the ministry. A correct reading in the original language points out that the “official ministers” are to equip and enable the “general ministers” (all the saints, or all believers) to do the ministry. In a constituency that depends too much on full-time staffs, the correct idea of ministry is an endangered species. A new emphasis on the role of the pastor, or missionary, as an “equipper of the saints for the work of the ministry” is urgent. This will result in new converts who from the first will discover their gifts and be active in Christian ministries. A correct theology of mission needs this emphasis.

A sixth factor in the theology of Mission relates to the missionary nature of the Holy Spirit. The place and purpose of the Holy Spirit must be emphasized in a theology of mission. This emphasis is especially imperative in our day in light of the charismatic movement and the burgeoning Pentecostal growth on many mission fields. Missionary advance has always been preceded by genuine spiritual awakenings such as the Pietist movement on the Continent, the Wesleyan revival in England, the Great Awakening in North America, the Moody campaigns, the youth revival movement among Southern Baptists, and the Billy Graham campaigns across the world.

Modern missiology must give more attention to the role of the Holy Spirit in the call, appointment, orientation, and maintenance of the missionaries. More emphasis on spiritual gifts and spiritual warfare is sorely needed. Spiritual renewal should be accepted, guided, and exploited in order to discover new methods of evangelism, worship, and personal development. It is the radical therapy that, at times, is the only remedy for broken interpersonal relations, demonic interference, and moral laxity that beset the missionary enterprise. Coming to terms with spiritual renewal will be a primary task of a correct theology of mission.

The above elements of a theology of mission are selective, not exhaustive. They are representative of all Christian doctrines that should be examined missiologically. They should be sufficient, however, to show the importance of the study of Mission theology as a component part of missiology.

History of Missions

Once a firm theology of Mission has been formulated, the missiologist must consider the history of missions before formulating his or her philosophy of Missions. Limitations of space in this introduction, the vastness of this component, and the treatment in other parts of this volume make possible only a cursory mention of this area of missiological study.

There is perhaps an unconscious tendency in contemporary missiology to downgrade the importance of missionary history and biography in order to give place to mission action, the behavioral sciences, church growth, and a myriad of faddish methodologies. This must stop! Historical study produces creativity and flexibility that are necessary for effective missionary deployment. Missionary history must be enlivened and inserted into the missiological curriculum. Some mission agencies act as if a vacuum is between the beginnings of Christianity and their day. The missions curriculum must include a wide spectrum of elements derived from the history of the expansion of the Christian faith. Both descriptive history and historical theology should be included. A selected, not exhaustive, list of historical topics for the missiological agenda illustrate the importance of this component:

- The definitive nature of New Testament missionary principles and methods. Should they be considered as normative for today?

- The presence of cross-cultural problems and ethnic divisions among New Testament Christians. Are they challenges in every generation?

- The rapid identification of Christianity with the Roman Empire. How do we deal with the imperialist problem in history?

- The historical development of the monastic movement from an inward renewal movement to an outward missionary movement. What does this say about similar movements today?

- A comparative study of the Celtic and Roman missionaries in the expansion of Christianity into Western Europe. Are there parallels in the contemporary situation?

- A study of the lives and methods of significant Catholic missionaries such as Francis of Assisi, Ramon Lull, Francis Xavier, Mateo Ricci, and Robert De Nobili. What of value exists in their methodologies?

- An analysis of the reasons the Protestant Reformers—Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and Knox—were not more missionary. Are some of these same reasons—faulty eschatology, deficient hermeneutics, theological controversy, and so on—impediments today?

- A study of the Pietistic precursors of the modern missionary movement and their influence on Carey and evangelical missions today.

- An assessment of the Protestant ecumenical movement from 1910 until the present. What caused it to detour from its original missionary purposes?

- A study of the evangelical ecumenism of the interdenominational, parachurch groups and their relation to denominational missions.

- An overview of your own denominational missionary history. What does it have to learn from other denominations?

And missionary history includes even more paradigms that are instructive for missiology today.

In conclusion, missionary history should engender overall optimism. For instance, the modern missionary movement, even with its patent weaknesses and mistakes, is a great success story. It has made Christianity a universal faith for the first time in its history. The pessimism heard today with reference to missions is not based on historical fact. Geographical expansion and cultural penetration of the missionary movement have brought Christianity to what could be its finest hour. This is no time for it to lose its nerve.

Philosophy of Mission

A theology of Mission plus the history of missions will produce a philosophy of mission. A definition of the term philosophy of mission could be the following: “The integrated beliefs, assertions, theories, and aims that determine the character, the purpose, the organization, the strategy, and the action of a particular sending body of the Christian world mission.”

A perusal of missionary history reveals some classical philosophies of mission. The study and evaluation of these philosophies, or schools of missions, is another task of missiology. It is a requirement for the formulation of pertinent, effective philosophies of mission today. A brief enumeration of these philosophies, described by key words, follows:

- Individualism. This philosophy assigns the Christian mission to the individual. In other words, the faith will spread through the personal witness of individual Christians. It eschews all structures, organizations, and societies of missions and assumes that Christians should witness wherever they happen to be. There is no intentional mission, only a casual, passive witness. Martin Luther seems to have espoused this philosophy. He said that if Lutherans happen to have contact with the Turks or the Jews, let them witness to them, but he never seemed to think of an intentional sending of missionaries to the Turks or the Jews! Many Christians unconsciously support this philosophy.

- Ecclesiasticism. This situation exists where the mission is a department of a structured, hierarchial church, or an order of a church. Most of the Roman Catholic or Orthodox missionaries fall under this philosophy. Augustine of Canterbury, the famous Catholic missionary to England, was ordered by the pope to go as a missionary. He went, not responding to personal vocation, but in obedience to an ecclesiastical authority.

- Colonialism. This philosophy exists where the mission is a department of state. It requires a state-church relationship where the state underwrites the missionary and the church selects and sends him out. An example of this philosophy is the Danish-Halle Mission to South India. The Danish king financed the mission carried out by the Halle missionaries.

- Associationalism. This philosophy exists where individuals or churches voluntarily associate themselves together to sponsor a mission. Associationalism has assumed two forms: the missionary society made up of individuals or the missionary board made up of representatives from local churches. Most free-church, Baptist, and evangelical missions follow this philosophy.

- Pneumaticism. This philosophy exists where the mission is inspired, supported, and carried out by the direction of the Holy Spirit and by persons and groups compelled by the Spirit’s leading to support the mission. It has been called the “faith missions” movement pioneered by Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission. The approach waits on the Holy Spirit to provide the vocation, direction, and support of the mission.

- Supportivism. This philosophy exists where the mission exists to serve other missions. For this reason it has been called the “service mission” movement. Examples of this philosophy are the Missionary Aviation Fellowship, the Bible societies, and a host of support missions.

- Institutionalism. This philosophy exists where the mission centers on the support of a single institution, such as a hospital, an orphanage, a good-will center, or a school. All of the structure and the purpose of such a mission is the maintenance of the institution.

- Ecumenicalism. This philosophy exists where the purpose of the mission is the promotion of Christian unity in one form or other. Missionaries are sent out to be agents of church union and to promote schemes to try to heal the divided denominations of Christianity.

- Pentecostalism. This philosophy depends on signs, wonders, miracles, healings, exorcisms, and charismatic manifestations to attract large crowds to hear and respond to the gospel. It is represented by the large Pentecostal churches around the world.

These philosophies should be studied, assessed, compared, and appropriated by missiology. Most of them have adherents in the world of mission today. Missiology helps the contemporary mission groups to arrive at their own philosophies, which, many times, are combinations of the classical forms mentioned above.

Cross-Cultural Strategy

Once the missiologist defines his or her philosophy, the next area of study and instruction is the strategic implementation of that philosophy in a given cultural setting. Here the whole matter of cross-cultural communication of the gospel comes into play. The first step is to analyze the “cultural setting.” However, before the particular setting of a given mission field can be understood, it must be seen in the light of the global setting. Seeking this understanding is the task of the missiologist. The missiologist must stay abreast of the global characteristics in a given moment of history. For example, the following are characteristics of the present world mosaic that have a bearing on the communication of the gospel by the cross-cultural missionary.

- A growing revival of the supernatural. Humankind seems to be tiring of a materialistic, positivistic world. Humans are weary of living by bread alone. Once again there is a rumor of angels; Plato is back! Men and women are nostalgic for the transcendent. This trend is seen in the new aggressiveness of the ancient religions, in the renewal of the occult, in the New Age movement, in the robust charismatic movement, and in the biblical revival among the ancient Christian traditions. Judeo-Christian secularization has created its Baal-peor called secularism; but humankind, made in the image of God, longs for something more. The Christian mission must be sensitive and responsive to this point of contact.

- The growing influence of the Two-Thirds World. Formerly called the Third World, these countries that were not aligned with either the First World (the USA and its western European allies) or the Second World (the Sino-Soviet Union, communist world) now constitute two-thirds of the world’s population and two-thirds of the world’s territory. They happen to be the scenario where cross-cultural communication of the Christian faith is attempted. Therefore, the study of their situations and felt needs is the task of missiology.

- The principle of acceleration. Things occur much faster than in previous times. No longer do the Greek cyclical or the Judeo-Christian linear images accurately describe the process of history. These processes, in other years content to develop over a long period of time, seem to “rev up” their engines and lurch forward at blinding speed. Missions can no longer afford to plod! Highly efficient but slow-moving mission bureaucracies must give way to more flexible, quick-moving “ad-hocracies!”

- The demise of the noble savage. Given that the savage was never really noble, today he is rapidly disappearing. In other words, what Westerners call “the primitive world” is in rapid transition. Urbanization and civilization are gradually pushing back the proverbial “bush” and exposing these primal peoples to the modem world. Missionaries, highly trained in anthropology and linguistics, are needed to give them a welcome to the Christian faith.

- The crowded global village. A demographic problem is creating havoc all over the world. Christianity is keeping up remarkably well, but one wonders for how long. Much will depend on the sensitivity of Christian missions to the urban challenge. Ways to reach the masses in the cities without losing the essentially personal nature of the faith must be explored.

- The demise of world socialism. The sudden fall of Marxist-Leninist socialism has left a spiritual vacuum in great sectors of the world. This presents an unexpected opportunity for the Christian mission if it can respond positively.

- The shifting economic center of gravity. The Christian mission no longer counts on a monopoly of the world’s economic capital. It no longer has a neocolonial umbrella. Other religions are economically competitive and aggressively active.

- The revolutionary nature of the world. The Christian mission must perform its task in the midst of political, social, and economic revolution. It must not be reactionary. Somehow it must empathize with authentic revolution and leaven it with revolutionary Christianity.

Once the missiologist has become aware of the global mosaic, he is better able to analyze a particular mission field or a given cultural setting. At this point, missiology has to define culture and teach future missionaries how to “read” a culture. All the research of the behavioral sciences—anthropology, sociology, psychology—as well as linguistics, are employed to make possible a cultural penetration. The several layers of culture are analyzed, and cultural barriers are anticipated. The phenomenon of culture shock, so detrimental to effective adjustment and cross-cultural communication, is defined and anticipated. Ways to overcome it are discussed. “Cultural overhang,” or “lag,” is isolated, and means to avoid it are presented. The religious aspect of each culture is examined.

At this point, the whole question of a theology of religions is addressed and approaches to the other religions are considered. With different views—called exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism—in mortal conflict among theologians, some missiologists feel that this “theology of religions” is the most crucial question in their field today.

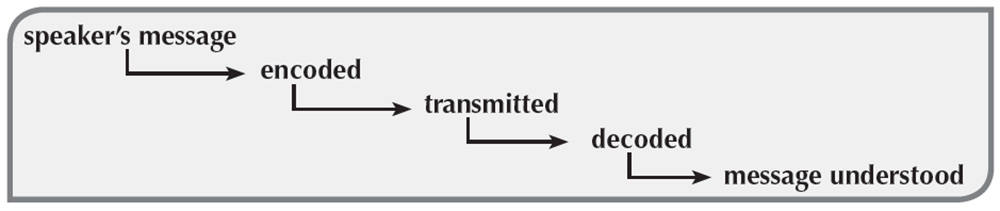

Communication principles are employed to facilitate the task of translation of Scripture and the explanation of the biblical truths in the idiom of the new culture. Ethnocentrism and cultural imperialism are shown to be the principal enemies of successful cross-cultural communication. Strategies to implement the cross-cultural principles wrap up this important unit of missiology.

Conclusion

In summary, the fleshing out of this formula of content presents an overview of the whole field of missiology, which the rest of this volume intends to treat in detail. Missiology, after many vicissitudes, has won its place in theological education. Although it is now a separate discipline with its own integrity, it is vitally related to the other disciplines and would hope to be an integrating center around which all can gather.

Chapter 2

The Purpose of Missions

Gerald D. Wright

We live in an era preoccupied with the issue of purpose. This preoccupation is seen in books such as The Purpose Driven Church by Rick Warren and God’s Missionary People: Rethinking the Purpose of the Local Church by Charles Van Engen. Institutions and churches rush to formulate purpose statements. This current fixation on purpose may reflect a widespread concern that efforts should be directed toward consciously determined ends and also may reveal a certain uneasiness about the value of many traditional endeavors. This issue of purpose holds special importance in the realm of Christian missions.

Without a clear understanding of purpose, efforts that issue out of the best of motives may lose focus. Even worse, when the church loses touch with its God-given purpose, its energies quickly become institutionally focused and self-serving rather than self-giving. The enormous challenges, demands, and opportunities of modern missions make it essential that the church possess a clear, biblically and theologically sound understanding of the purpose of missions.

A Plurality of Understandings

While one might think that the purpose of missions is self-evident, the late David Bosch in Transforming Mission (1991) demonstrated that the missionary efforts of the church through the centuries have reflected considerable variety with regard to purpose. This variety has ranged from the embodiment of agape to the “Christianizing” of culture to the expansion of Christendom, both in terms of government and orthodoxy. Bosch concluded his impressive survey with a summary of what he called “emerging paradigms,” which further enlarged the potential scope of missions’ purpose, encompassing missions as missio Dei, enculturation, liberation, and ministry by the whole people of God, to name a few.

A cursory examination of current texts in missiology reinforces this perception of diversity. Waldron Scott (1980) emphasizes establishment of justice. Charles Kraft (1979) and others, working from an anthropological perspective, consider missions a process of cross-cultural communication and contextualization. They emphasize mission activity as the incarnation of the gospel. John Piper (1993) relates the purpose of missions primarily to worship and proclamation in the context of the glory of God. Lesslie Newbigin (1995a) considers the purpose of missions in relation to the kingdom of God understood from a trinitarian perspective. In earlier centuries, missions for William Carey, as for many of the Anabaptists before him and the Baptists who have followed him, was understood primarily in the context of the Great Commission and its command to make disciples among all nations.

These diverse understandings of the purpose of missions result in part from varying interpretations of the biblical and theological foundations of missions. Which biblical texts should be given primary force: the Great Commission, the Old and New Testament covenants, the theological formulations of Romans, or the eschatological emphases of Revelation? Which doctrines should be determinative: the nature of God, Christology, pneumatology, ecclesiology, soteriology, eschatology?

This diversity has been compounded in modern times by the influence on missions of disciplines such as communication theory, anthropology, and sociology. Different voices within different traditions at different times have offered varying understandings of the purpose of missions.

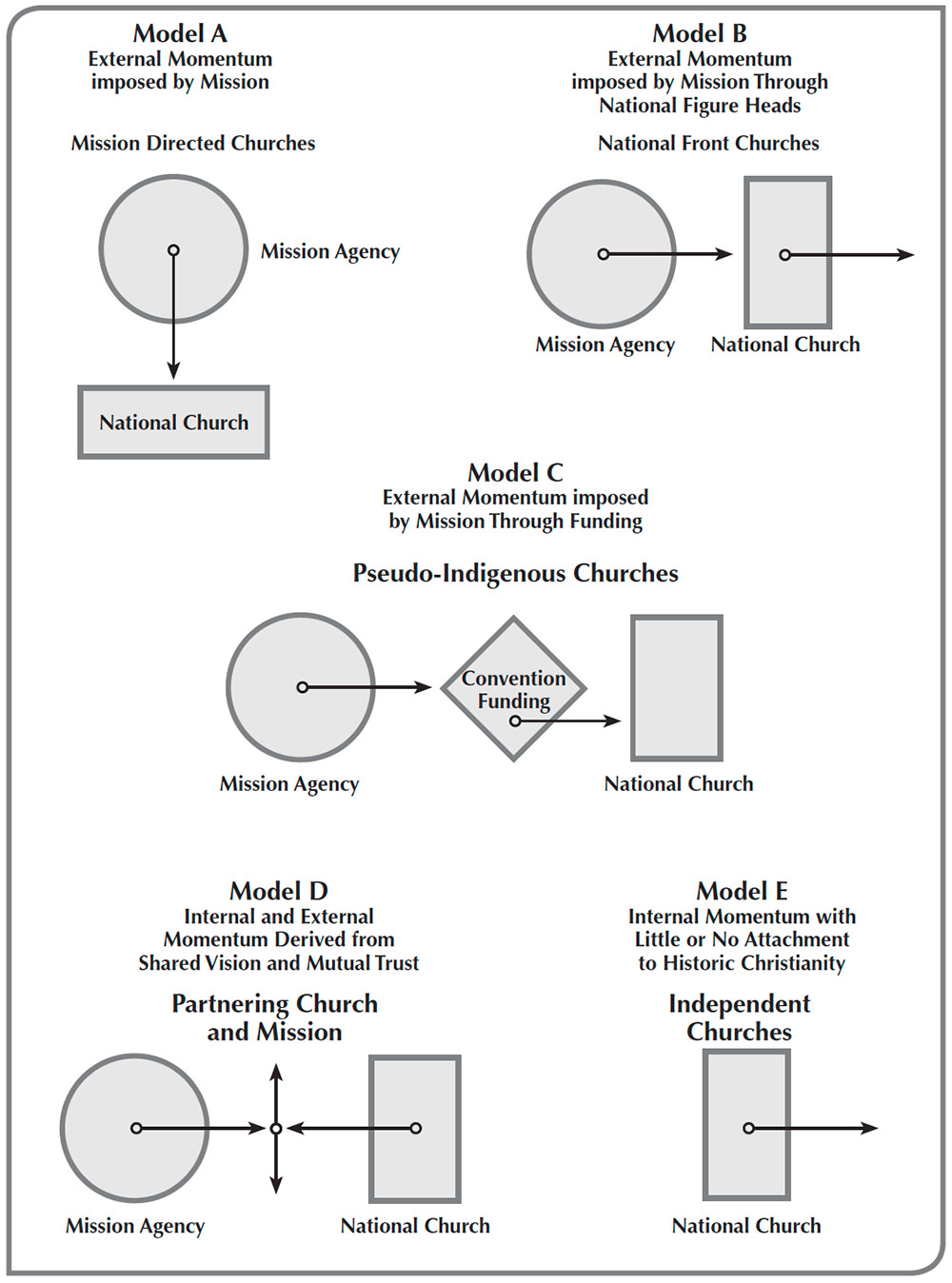

Against this background of plurality and complexity, the trustees of the International Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention adopted, in February 1995, a remarkably simple and straightforward purpose statement that asserts that “our basic purpose is to provide all people an opportunity to hear, understand and respond to the gospel in their own cultural context.” Several aspects of this understanding are significant. While there is emphasis on proclamation, there is also emphasis on understanding and response, and all within the cultural context of the hearers. Hence, the purpose of missions is not fulfilled until the gospel has been presented in the most viable way possible in view of the particular cultural setting.

The same International Mission Board document states that the basic task of the missionary is “evangelism through proclamation, discipling, equipping, and ministry that results in indigenous Baptist churches.” The emphasis, then, is clearly upon evangelism; but the instruments of evangelism are identified as proclamation, discipling, equipping, and ministry. Indigenous churches are generally understood to be churches that are self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating. Some missiologists would add “self-theologizing” to the characteristics of a truly indigenous church.

The Southern Baptist Convention’s Covenant for a New Century expresses the purpose of the North American Mission Board as proclaiming the gospel, starting New Testament congregations, and ministering to persons in Christ’s name, as well as assisting churches in fulfilling these functions. The statements of these two Southern Baptist missionary entities demonstrate a similarity of understanding as to the basic purpose of mission and missions.

Missions and the Light of the World

Missiologists strive to achieve balance between the different facets of missions. They seek biblical and theological foundations broad enough to afford a holistic approach yet restrictive enough to prevent blurring that perceives everything as missions.

Discussions have centered, at times, around the missio Dei (the mission of God into which the church is enlisted) or around the kingdom of God or around the glory of God. Each of these and other foci have proven helpful in the ongoing conversation about the purpose of missions. These perspectives complement and augment one another, forming a beautiful tapestry. The absence of any one from the whole detracts from the beauty and fullness of the total picture.

To those who embraced the kingdom of God, Jesus said, “You are the light of the world” (Matt 5:14 NASB). This expansive and emotive image of the nature and purpose of missions connected with Old Testament missiological themes and related the purpose of missions to the nature of the godhead and to Jesus’ own mission. The entire tapestry of the purpose of mission can be viewed as an expansion of the metaphor of God’s people as the light of the world.

Jesus used images that defied strict, mathematical equivalency and that beckoned the hearer to reflect in order to understand. He spoke of bread and water and seed and leaven. His parables, too, invited reflection. His miracles were “signs” that, when properly understood, conveyed truth about his nature and mission. Light was one of the terms used by Jesus that called for reflection and that overflowed with meaning for the hearer seeking truth.

The concept of light had important missiological roots in the Old Testament. Isaiah envisioned a servant of God who would be a light to the Gentiles (Isa 42:6). In a striking passage God declared of his servant, “It is too small a thing for you to be my servant to restore the tribes of Jacob and bring back those of Israel I have kept. I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring my salvation to the ends of the earth” (Isa 49:6 NIV 1984).

These and other passages in Isaiah make it clear that, for the prophet, light was indeed a missiological term related to God’s purpose of making himself known to the nations, the Gentiles. Jesus maintains this missiological focus in his own statement, for the world is the recipient of the light shining forth through his disciples.

Light and Knowledge

Several purposes of missions are discernible in the imagery of light, which of course has to be understood against the opposing imagery of darkness. First, light suggests knowledge while darkness suggests ignorance, as anyone who has ever stumbled around in the dark of an unfamiliar environment in search of some item can well comprehend. Where there is no light there is no knowledge, and what better than darkness could describe the plight of a world without the message of redemption and hope? In this context, light is closely associated with revelation and with the glory of God and implies knowledge of God. Hence, Paul could speak of “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ” (2 Cor 4:6 NIV 1984).

An essential aspect of missions, therefore, is proclamation, the imparting of the knowledge of God through the Good News of Jesus Christ, particularly his sinless life, crucifixion for our sins, resurrection, and coming return in glory. Proclamation was central to the mission of God’s servant described by Isaiah, who was to proclaim good news to the poor, liberty to the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, and the era of God’s favor (Isa 61:1–2). Jesus, of course, made exactly this proclamation.

The kingdom of God was central in Isaiah’s mission as it must be central in ours; only now, as Lesslie Newbigin has observed, that kingdom has a name and a face—Jesus of Nazareth (Newbigin 1995a, 40). If the church is to fulfill its mission as light of the world, it must be faithful and clear in proclaiming the gospel and imparting the information essential to an understanding of salvation and an experiential knowledge of God through believing in the Lord Jesus Christ.

Light and Good Deeds

Proclamation, however, is more than words. Jesus proclaimed God’s kingdom in word and deed. Just as the parables proclaimed the kingdom in words, the miracles proclaimed the kingdom in deeds. This, too, had been a part of the missiological vision of Isaiah, for in bringing light to the Gentiles the servant would open the eyes of the blind, free those in bondage, and bind up the brokenhearted (Isa 42:7; 61:1).

The church today, likewise, must proclaim God’s message by word and in deed. In fact, it is often the proclamation in deeds that validates and authenticates the proclamation in words, and vice versa. Quite appropriately, then, home and foreign missions have emphasized the importance of ministry to people’s needs, sponsoring homeless shelters in the inner city, agricultural projects in underdeveloped areas, medical missions, and a host of other ministries.

Light denotes good deeds, even as darkness suggests evil deeds. The Gospel of John, for instance, speaks of the light coming into the world and being rejected because people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil (John 3:19). Evil deeds are hidden under the cloak of darkness, but deeds of righteousness can be done in the light. When Jesus declared his followers to be the light of the world, he exhorted them to let their light shine so that the world would see their good deeds and glorify God.

Good deeds—ministry to the hurting, humanitarian aid, medical missions, social ministry, or some other form of compassionate action—glorify God. But Christ must also be proclaimed through actions that demonstrate the power of God and of the gospel. Paul reminded the Corinthians that his proclamation in words had been simple and straightforward, but it had been accompanied by demonstrations of divine power (1 Cor 2:4).

If the missionary today is to be an instrument of light in a world of darkness, the power of God should be evidenced in redemptive deeds. Proclamation in words that neglect the actions properly associated with children of light will be hollow indeed. Furthermore, proclamation in actions without accompanying words will stop at mere sentimentality, addressing the needs of the moment but leaving unanswered the greater and eternal need.

Word and deed must never compete with each other, as though one were diminished by the other. Word and deed clarify and define each other. Either one without the other is shallow and impotent, but together they shine as light in a dark world. Both, however, must be exercised under the empowering of God’s Spirit.

Joy and Hope

Light, as used both by Isaiah and Jesus, suggests joy and hope in contrast to the gloom and despair of darkness. Isaiah (9:2–7) describes a people dwelling in the despair of darkness and oppression. When the light dawns upon them, however, their gloom turns to joy, as people who celebrate a bountiful harvest or as warriors who divide the spoil after a great victory. Such is the joy when the darkness is shattered by the light of missions.

Upon graduation, a seminary student in West Africa was called to pastor a village church in an area where Christian work was undeveloped. Because he had been called into the ministry later in life after a career in civil service, the pastor easily could have gone to a much larger city church in a more developed area; but he felt the leadership of God to the village.

Within a few months of his arrival, he began to notice signs of a new prosperity among the believers; and as the months passed the prosperity increased. Some who had been riding bicycles purchased motorcycles. Others plastered over their mud walls and floors with cement or replaced the thatched roof on their houses with a new tin roof. Their contributions to the village church increased significantly.

The pastor’s curiosity grew until, finally, he asked his church members why they had suddenly begun to prosper. He expected that they would share amazing stories of how they were materially blessed after they professed Christ. Instead, they told him that their prosperity really had not changed, but that before they came to Christ they had been afraid to show any sign of being blessed for fear that an envious neighbor might use dark spiritual powers against them, bringing harm on their households. In their spiritual bondage of fear and darkness they had been afraid to prosper.

It is little wonder that in such settings exuberance is in Christian worship, for believers know that the light of Christ has brought joy and hope to their lives. Nor is it surprising that joy was such a common manifestation among the Christians of the New Testament and was listed among the fruit of the Spirit by Paul. The mission of the church and of Christians, as the light of the world, is not only to spread the knowledge of God through proclamation accompanied by the deeds of light but also to bestow joy and hope, dispelling the darkness of gloom and despair.

Light and Spiritual Warfare

All of this, of course, presupposes a kind of spiritual warfare, a confrontation between light and darkness. Those who live in darkness are in bondage to the powers of this dark world, against which Christians must wrestle. Darkness is in part the result of a rejection of God’s glory (Rom 1:21) and in part a work of the “god of this age” who has blinded the minds of unbelievers (2 Cor 4:4). Throughout the New Testament, Christians are reminded that they have been delivered from the kingdom of darkness into the kingdom of light and are to walk in the light, shunning every form of compromise with evil and darkness.

Nowhere is this confrontation with darkness more evident than on the mission fields, at home or abroad. When missionaries cross barriers or enter neglected sectors of the world and society, they are invading Satan’s domains. Indeed, confronting the forces of darkness (invasion of these darkened domains) is a primary purpose of missions. It is not surprising, then, that God instructed Paul to turn the Gentiles “from darkness to light and from the dominion of Satan to God” (Acts 26:18 NASB).

The most critical need, then, is not for more money or better strategies, though these are vital, but for an awareness and appropriation of spiritual equipping and empowering from God. Those who have carried the light into the dark corners of the world and of society know the importance of this empowering, for they have seen firsthand the fear and despair. They have experienced the struggle against evil in which Satan’s territory is yielded only with the utmost exertion of all one’s resources. They have seen their every effort openly opposed by the Evil One.

The Ephesian Christians had to contend with the powers of darkness. Paul prayed that their eyes would be opened to know God’s great power on behalf of believers, a power demonstrated in the resurrection of Christ from the dead and in their own resurrection from the deadness of trespasses and sins into the life of Christ (Eph 1:18–2:7).

Paul’s prayer makes it clear that the needed resources for victorious living are available and need only be appropriated. Missionaries, therefore, need not tremble before the darkness, for their weapons of warfare are not of the flesh but are divinely powerful so as to destroy the fortresses of the Evil One and take every thought captive for Christ (2 Cor 10:3–5).

To undertake the work of missions without such spiritual weapons and knowledge of how to use them, therefore, is futile and even foolhardy. The missionary’s weapons include righteousness, faith, truth, the Word of God, and a readiness to share the gospel, all exercised with vigilant prayerfulness (Eph 6:13–18).

It is impossible to overstate the importance of prayer in this conflict with darkness. Prayer is the primary instrument by which God’s available power is appropriated in the life of the missionary. One of the great stories of contemporary missions is the story of how God has used prayer to open doors to unreached people groups, bringing light to those in darkness. Even so, we still have much to learn about missions praying and about the relationship between prayer and victory over the forces of darkness. And we still may have important lessons to learn about the nature of this warfare.

If a part of the purpose of missions is to confront and oppose the powers of darkness, then missionaries need a clear idea of the enemy and his tactics. Fortunately, the Scriptures provide detailed information concerning Satan’s activity. He is the adversary, the accuser, the destroyer, the deceiver, the liar, and the murderer who holds people and peoples in bondage. In contrast, God reveals himself as our advocate and defender, as one who gives life abundantly and leads into all truth, who sets free those who are in bondage. These respective traits may seem so familiar as to be trite, but they are vitally important and need to be kept in mind whenever missions is pondered.

Missionary service is modeled on the character of God. Consequently, the missionary goes to the world as an advocate, not an adversary; goes in truth, not in deception or falsehood; goes to set free, not to enslave.

Light and Culture

Another purpose of missions that is integral to the calling to be light in a dark world concerns the missionaries’ relationship to culture and society. On the one hand, missionary service demands cultural adaptation that aims to permeate and transform culture. It also requires confrontation with culture. Interestingly, this tension is depicted in the biblical imagery of light, for light both transforms and exposes.

Like the salt and leaven also used by Jesus to depict his followers and their influence, light is an agent of transformation. As such, it illuminates the landscape or dwelling, making it manageable and even hospitable. Much that is of value may be in the setting, but unless it is transformed by the light, it remains cloaked in darkness and marred by sin.

Even so, within cultures there may be much that is noble and of value. Without the light of Christ, however, such inherent value cannot be truly appropriated. On the other hand, light exposes all within the setting that is undesirable or detestable, uncovering the evils of individuals and societies. Light confronts the deeds of wickedness, stripping away the protection of darkness.

This tension between transformation and judgment is reflected theologically in the tension between the incarnation and the cross. In the incarnation, we see God adapting himself to humanity and condescending to human culture. In the cross, however, we see God’s judgment on sinful humanity and fallen culture. One of the weaknesses of Charles Kraft’s work in Christianity in Culture is that he works almost exclusively from the perspective of the incarnation without the tension of the cross. Consequently, Kraft thinks primarily in terms of transformation and not in terms of judgment upon culture. On the field, missionaries may be tempted to sacrifice this tension, either completely embracing or totally repudiating their host culture. But the tension implied by the light, which both transforms and exposes, needs to be maintained in missions.

There is, then, a mission purpose with regard to culture that requires transforming and validating within a culture that which has value and can be placed in the service of Christ, and exposing and rejecting that which belongs only to the darkness and can never be compatible with the kingdom of light. Expressions of culture must be judged as to whether they have positive value, are neutral, or constitute a negative presence in the setting and need to be opposed. Sometimes sorting out these issues is difficult, for cultural elements may not be what they seem in the eyes of an outsider. Missionaries have often drawn conclusions without the necessary cultural understandings.

These questions must be addressed prayerfully under the guidance of the Holy Spirit and with the help of indigenous Christians. Kraft warns that the missionary can advocate cultural change but that only cultural insiders innovate in achieving change (Kraft 1979, 360–70). Further, time must be allowed for the Spirit of God to work in individuals to bring about the necessary transformation of culture or rejection of culturally entrenched evil. Still, these principles may prove difficult to apply if the missionary encounters a practice such as sati, the Indian practice of burning alive a widow on the funeral pyre of her husband—a practice vehemently opposed by William Carey.

A Community of Light

The calling to be light is also a calling into the fellowship of light. Paul saw Christians as being joined together in a community by which they could encourage and strengthen one another as children of light (Eph 5:8, 15–20). Similarly, John was emphatic in that if Christians truly walk in the light, they have fellowship with one another as common members of God’s family in a relationship defined by love (1 John 1:7; 2:8–11). Surely the task of missions is not fully accomplished until believers are united in communities of faith, fellowships of light, and loving spiritual families. It is from within such a fellowship that the light of Christ can best shine through his followers, and the creation of such fellowships is integral to the mission task.

Being God’s light in a dark world, then, means overthrowing ignorance with the knowledge of God. This ministry includes countering the evil deeds of darkness with deeds of righteousness and light. The ministry of light involves bestowing joy and hope in Christ where gloom and despair are and engaging the powers of darkness in spiritual warfare in the power and name of the living Christ. The ministry of light includes both transforming and confronting culture.

Light, then, is a fitting metaphor for mission and a guiding standard for missions. Christians are called into the light of eternal life and commissioned to take this light to those in darkness. An effective witness must show this light by proclamation, ministry, and spiritual warfare. Good deeds done in the name of God and the power of the Holy Spirit do much to show the light of God’s message.

As ministers of God’s light, missionaries must act as both supporters of indigenous culture and judges of local culture. While missionaries will advocate cultural change, they must allow local people to effect changes. Some cultural elements may remain as part of the reception of light, but others will have such marks of darkness as to be untenable in the Christian context.

Believers, as children of light, should be drawn into the communities of light, local Christian fellowships. As Christians share the nature of light in God, they live together in the essence of the fellowship of light. Only as the churches exemplify the light in joy, unity, hope, and service can these congregations share the mystery of salvation. Light sums up much of what mission and missions is all about.

The Nature of God and the Mission of Christ

The calling to be light also draws missions into the sphere of the nature of God and the mission of Christ. John declared, “God is light; in him there is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5). Similarly, Paul described God as dwelling in “unapproachable light” (1 Tim 6:16). Indeed, Paul had encountered the risen Christ on the road to Damascus as a blinding light. Further, Jesus declared himself to be the light of the world, promising that those who followed him would not walk in the darkness but have the light of life (John 8:12). It is only because Christ is the true light that Christians are light. Stated differently, Christ is the light, and Christians become light as they are properly related to him.

The designation of Christians, and particularly of missionaries, as the light of the world is a reminder that they are called to be partakers of the divine nature with him who is by nature light. Missionaries are called to join in mission with the one who has shown in the darkness bringing light to the nations. “As the Father has sent Me,” Jesus said, “I also send you” (John 20:21 NASB). To be light in a dark world, then, is to share in God’s nature and to share in Christ’s mission.

Consequently, arrogance and pride have no place. Paul, having contemplated the mystery and grandeur of the God of light who has shone in our hearts, went on to declare that “we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us” (2 Cor 4:6–7 niv 1984). This recognition can only produce humility and gratitude to God for his indescribable grace.

Is Everything Missions?

As was suggested earlier in this chapter, missionary leaders must avoid two extremes in working out an understanding of the purpose of missions. On the one hand, the purpose of missions should not be so narrowly defined that vital missions concerns are overlooked or obscured. On the other hand, the purpose should not be stated so generally that everything becomes missions. Then the danger arises that the more critical concerns will be overshadowed by a host of lesser concerns, and missions will lose its direction.

Two aspects of missions as sharing God’s light help protect missions from being diluted or becoming too generalized. First, missions must display an overriding concern for the glory of God. Jesus indicated that the ultimate purpose of his followers should be to incite others to glorify God (Matt 5:16). John Piper has developed some of these concerns in his book Let the Nations Be Glad: The Sovereignty of God in Missions. Missions should always be viewed within the context of its ultimate purpose of leading a lost humanity to join with all creation in praising and glorifying the living God.

Second, the calling to be light requires prioritizing missions in favor of those in darkness. Of course, all who do not know Christ are in darkness; but there are also degrees of darkness related to factors such as availability of the gospel, accessibility of Christian worship, the existence of Scripture and related Christian literature in the heart language of the target people, or the presence of oppressive structures and traditions. Missions must be zealous to take the gospel to the darkest corners of the world and of society so that every creature has the opportunity to receive the light of Christ.

Some Christians may be led to emphasize some part of the mission as the particular expression of missions for their group. This arrangement is not necessarily in error so long as the particular ministry (literacy, children’s work, medicine, education) is not presented as the way to do missions. The entire body of Christ should express the entire mission to win and develop people, meet their physical and spiritual needs, and bring them into fellowships that influence and transform their communities.

Everything is missions and missions is everything. The only care that must be expressed is that we not allow any expression of missions to be the entire mission. The body of Christ must be careful to express the entire meaning of mission in the particular expression of missions around the world.

A Unifying Image

It is important to be reminded at this point that every Christian is called into God’s service to be light in a dark world. When Jesus said, “You are the light of the world” (Matt. 5:15 NIV), he was talking to more than simply missionaries. Yet the calling to be light has special relevance for the missionary and for the mission of the church to a lost world. While not every Christian is called to be a missionary in the strict sense of the term, every Christian is called to be part of God’s total redemptive purpose.

The part of some, those whom we call missionaries, is to cross the barriers that separate people from the gospel and present them with the knowledge, claims, and character of God. Their calling does not make them holier or more valuable than other Christians, but it does require special giftings from God that enable them to become bicultural, to be severed from kin and country, and to recognize avenues of proclamation and ministry in settings different from their own.

All Christians, however, are part of God’s mission, his one mission of making himself known to all the people and peoples of the world. One of the most dramatic mission developments of this era has been the emergence of volunteers in missions. Christians in unprecedented numbers, who are not career missionaries, have voluntarily taken up the missionary banner and joined forces with vocational missionaries to share the light of Christ with the world. Others who have not gone to the mission fields at home or abroad have committed themselves to remarkable levels of praying and giving for the cause of missions. This merging and partnering of all Christians with those who are called by God as missionaries is essential if the missionary task is to be accomplished.

Mission and missions must be the consuming passion of the whole church of God and not the exclusive domain of an elite missionary regiment. Only then will the church be like a city set on a hill that cannot be hidden. Only then will the fullest meaning of mission as the light of God be realized.

Conclusion

The purpose of missions must be understood and articulated in ways that are biblically and theologically sound, avoiding a focus that is either too narrow or too inclusive and making missions a vital concern for the whole people of God. Jesus’ designation of his followers as the light of the world at once places the purpose of the church in a missiological framework based on the Old Testament expectation of a light to shine upon the Gentiles and the dark places.

This understanding of the purpose of missions centers on the proclamation of the gospel of Christ by word and by deed while displacing ignorance with the knowledge of God, evil deeds with deeds of righteousness, and despair and bondage with joy and freedom. Missions, then, means engaging and overthrowing the powers of darkness in the power of God. It entails an encounter with culture that both confronts and transforms.

Further, the calling to be light identifies missions with the God who is light and with the light and life-giving mission of Christ. Mission can be fully realized when believers are called into the fellowship of churches where the light of the gospel is lived out in love, unity, and service. Finally, it requires endeavor that glorifies God and that favors those who, by virtue of their social or geographical location, are in the greatest darkness.

Chapter 3

Missiological Method

Bruce Ashford and Scott Bridger

Missiology is a theological discipline, that is undertaken in conversation with Scripture, church history, and the social sciences and in consideration of its cultural context. One of the most formidable challenges facing missionaries and mission agencies today is the imperative to ensure that missiology remains a theological discipline, rather than making it a subset of the social sciences or captive to a particular cultural context. Missionaries must forge their ministry practices in the furnace of Christian Scripture and evangelical theology. Although evangelical missionaries, agencies, and seminaries declare their belief that Scripture is inspired by God, this belief sometimes is disconnected from our actual mission practice. When we allow this type of disconnection, we imply that what we believe about Scripture is important, but how we apply it on the mission field is not. This type of disconnection between belief and practice will derail our mission. In the following pages, we provide a brief treatment of some ways in which we can ground our mission practice in sound, biblically faithful theology, in conversation with church history, the social sciences, and our cultural contexts.

Theologically Driven Missiological Method

Missiology is a theological discipline, just as mission is a theological task. What, then, is “theology”? Christian theology is disciplined reflection on God’s revelation for the purpose of knowing and loving God, and participating in his mission in this world. From this definition, we can clearly see that “theology” is something in which every missionary is deeply interested. It is the impetus that drives the continual translation and transmission of the faith across linguistic, conceptual, and cultural boundaries. Andrew Walls writes, “Christian faith must go on being translated, must continuously enter into vernacular culture and interact with it, or it withers and fades” (Walls 2002a, 29). The missionary participates in God’s mission out of his knowledge of God and love for God, and through consistent reflection on the Bible.

One way that we can illuminate the task of theology is to understand its relation to four concepts: narrative, worship, obedience, and mission. First, theology arises out of Scripture and its dramatic narrative. The Bible is composed of sixty-six books written by numerous authors from diverse historical and cultural contexts. However, this diversity is part of a beautiful unity that constitutes the Bible’s overarching story. This story begins with God’s creation, is followed by humanity’s rebellion, and proceeds with God’s unfolding plan of redemption. This plan culminates in a renewed creation populated by worshippers from every tribe, tongue, people, and nation. The nature of the story is dramatic, inviting us into the story so that it can shape our lives. The nature of the story is also missional, sending us out to join God in his redemptive mission.