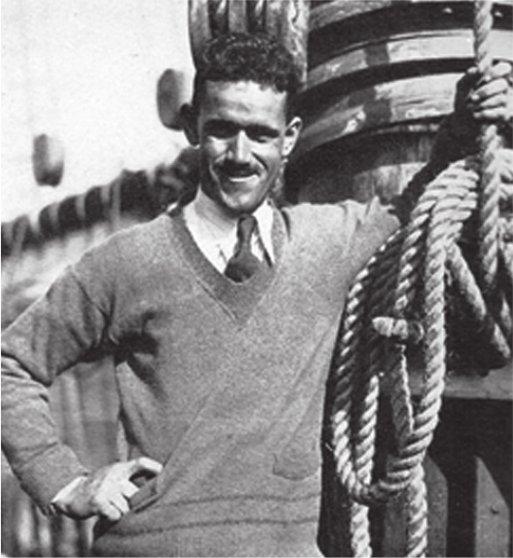

LARGELY FORGOTTEN sixty years after his death, his books rarely in print, Robert Dean Frisbie – a tall, humorous, skinny American who, just after the end of World War I, settled in the farthest reaches of the South Seas to write – was, in the words of James Michener, ‘the most graceful, poetic and sensitive writer ever to have reported on the islands.’ Frisbie realized a fantasy many men dream about: a tropical vision of island beauty which included local maidens, a large family, solitude to write in and surviving a hurricane. It meant tragedy, too, for after the death of Frisbie’s beloved Polynesian wife Nga, as a colleague wrote, ‘Paradise found his weakness and had no mercy.’

Robert Dean Frisbie was born in Cleveland in 1896 and grew up in California, nurtured on the South Pacific books of Robert Louis Stevenson. His health was frail; a WWI training camp left him under permanent threat of tuberculosis. In 1918 he received a medical discharge, a monthly pension of $45 and orders never to spend another winter in America. Frisbie happily obeyed.

He made his way out to Tahiti in 1920 and was immediately befriended and encouraged by that patriarch of expatriate writers in the South Pacific, James Norman Hall, later of Mutiny on the Bounty fame. Within a year Frisbie had bought four acres of land, taken a Tahitian mistress, learned the language, built himself a bamboo-and-palm house and acquired the name ‘Ropati’, which he would carry for life throughout the islands. He also started his relentless reading of ‘great books’ to make up for a lack of higher education. He began writing short pieces, sending them the long sea-road back to American magazines without success. He spent several years expensively refitting a yawl with a couple of friends. A three-thousand-mile sailing voyage, through the Society Islands, the Tuamotus and the Samoas, ended in Fiji after a heavy gale. Frisbie sold the wounded boat and returned to Tahiti.

Wanting an island more removed and deeply Polynesian, Frisbie in 1924 sailed from Tahiti to Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands, with the legendary trading-schooner captain Andy Thomson. Through Thomson’s intervention Frisbie got a job as the only copra trader and storekeeper on the remote northern Cook island of Puka-Puka, also known as Danger Island. Copra – dried coconut meat – was many South Pacific islanders’ only income.

Puka-Puka, with three villages and six hundred inhabitants, was over 700 miles from Rarotonga. Really three small islets in a lagoon formed by a barrier reef, it was about as far away from civilization as a Westerner could get. Left here by a supply schooner that would come only once or twice a year, Frisbie blossomed as a writer. He at last began publishing short sketches of his island life in the Atlantic Monthly, though the delay, of course, was immense.

To be Puka-Puka’s sole white man and storekeeper for four years was an ideal way to learn about the locals’ character, and he became fluent in their language. He enjoyed a few mistresses, but soon Frisbie married a petite island girl, Ngatokorua. They had five children, whom the Polynesians called ‘cowboys’ in honour of their American father.

Determined to write the great South Pacific novel, over the years he managed four, of diverse quality: Dawn Sails North (1949), Amaru (1945) and his best, the autobiographical Mr. Moonlight’s Island (1939) and My Tahiti (1937). These last two have tremendous local colour and feel for the people, but Frisbie lacked the sense of fantasy of a true novelist; his stories never quite live up to his material.

Frisbie’s two memoirs of life on Puka-Puka are his supreme achievement, however. As visions of South Pacific life, written from deep within the dream yet harbouring no illusions about it, both The Book of Puka-Puka (1929) and The Island of Desire (1944) have never been equalled. As the observed experience of a man living in a close relationship with nature while questioning the tenets of his own civilization, thankfully left far behind, they compare favourably with Thoreau. And Frisbie’s writing is always sublime. In The Book of Puka-Puka he writes, ‘Without a thought for the white man’s code of ethics, I have been happy, enjoying a felicity unknown in right-thinking realms.’ He describes how natives ‘sink into trances with perfect ease, bolt upright, eyes open, completely unconscious of the world about them,’ and he learned how, too. He had no illusions about Polynesians, seeing them as full of fantasy and short of memory – except for their family trees and poems, some of which he translated. ‘Puka-Puka is, perhaps, the only example on earth of a successful communistic government,’ he wrote, ‘… due to the fact that no other community equals this one in sheer good-natured indolence.’

Time after time, in both books, he caught exactly the sense of island life: ‘Of a sudden I understood: all this land and sea, dormant by day, had awakened at dusk, refreshed, hungry …’ He described an old woman ‘singing a little song as silly as it was beautiful’ and the ‘great seas bombarding the reef’ in a hurricane, in which he had to strap his children high up in tamanu trees so they were not washed away. Most moving of all, he described, after the death of his wife, a visitation by her ghost.

What makes his work so vibrant are the islanders: Sea-Foam the Christian and William the Heathen; Bones, the old wrestling champion, with his mouth organ; Ura the drunken chief of police; the beautiful Little Sea and her more tender cousin, Desire; the village debates, the gambling, fishing and gathering coconuts; the sensual dances by moonlight; the life of gossip, habit and ease.

In 1928 Frisbie and his wife left Puka-Puka for Rarotonga, and began two decades of moving from island to island. They had a happy and productive few years on Tahiti and neighbouring Moorea, even though Frisbie published little in that time and was beset by horrific fevers and elephantiasis. The solution to his acute physical torment was rum, and both followed him thereafter. He and Nga ended up back on Puka-Puka, but in 1939 his wife died of tuberculosis, and from then on Frisbie – no matter how much he wrote – was a haunted and doomed man. He wrote to his old friend James Norman Hall on Tahiti: ‘If I could only kill this cursed desire to write I could be happy. How can you expect a man who writes in English and thinks in Puka-Pukan to be able to know what kind of work he is doing?’ Frisbie would die penniless.

The Island of Desire, his other masterpiece, begins with him back on Puka-Puka and describes with great sweetness his renewed life there until Nga’s passing. The book’s second half covers his experience with his children on Suvarrow, an even more remote and uninhabited atoll of twenty-five islets where he took his family in late 1941. This desert island paradise was all but destroyed by a monstrous hurricane, and Frisbie’s account is unforgettable.

‘I hunted long for this sanctuary,’ he wrote. ‘Now that I have found it, I have no intention, and certainly no desire, ever to leave it again.’ But this wasn’t to be. Rescued from Suvarrow, always unhealthy, he took his family back to Rarotonga, then Puka-Puka, then Tongareva, where he contracted TB. (A Lieutenant Michener was put in charge of bringing the dying American writer back to the hospital in Pago-Pago.) Samoa had use for him as a teacher once he recovered, but his fevers and drink got to him badly and he ended up on Rarotonga. The administering New Zealand government, disgruntled at his alcoholism, tried to kick him off the island and his last years were frustrated by official bickering. Meanwhile, his books failed to achieve what he hoped, partly because war had brought a newer story to his isles.

Frisbie died of tetanus in 1948 and is buried on Rarotonga, across from the Avarua library, in a simply marked grave beneath a paw-paw tree in the Catholic cemetery. His eldest daughter’s own writings show us Frisbie as he would wish to be remembered – the inventive father, reading to his remarkably self-reliant children (‘Ropati’s Slave-Labour Gang’) from the thousand books brought to a remote isle. No outsider ever lived closer to South Pacific culture, lore and daily life than he, nor recorded so eloquently what it taught him, before he struck his own reef.

Today Robert Dean Frisbie is known mainly to those travellers to the South Pacific who look past the more familiar names and bother to hunt down copies of his books – which were in their day well received in England and the States. ‘A man who destroyed himself through the search for beauty,’ is how Michener described him. In some ways Frisbie’s extraordinary journey also seems the ‘standard’ American literary life: so much purity of expression ending in frustration and drink. Yet Frisbie’s poetic touch, his gentleness, his sympathy, are rare, and anyone dipping into his books feels immediately the unique warmth and tone of his voice. I like especially to remember a letter Frisbie sent to his brother:

The old man looks long across the lagoon and reminisces on his past futile days. Then he wades out until the water comes to his shoulders. He swims with long strokes until he is a mile or more from shore and quite exhausted, and realizes that now it is absolutely impossible for him to return. He rolls over on his back and stares heavenward, then he looks to land and suddenly he smells the fragrant mountain wind, sees the moonlight throwing the shadows of articulated ridges across the water. He, for the first time in his life, realizes that there is beauty.

Anthony Weller

2005

Those interested in the life as well as the work may wish to read The Frisbies of the South Seas (1959), by his eldest daughter, Johnny Frisbie, as well as her earlier book, published when she was only fourteen, Miss Ulysses of Puka-Puka (1947), which Frisbie co-wrote. The Forgotten One (1952), by James Norman Hall, contains an illuminating ninety-page essay on Frisbie, with excerpts from his letters. James A. Michener’s memoir, The World Is My Home (1992), has a good, brief, portrait too.