AFTER CROSSING THE REEF we pulled the boat over a long stretch of shallow water, rowed across a bay formed within the bight of the main islet, and ran her stem upon a white coral beach. A few sleek-skinned children came running‚ open-mouthed, stopped abruptly a few yards away, and stood motionless.

An old woman with a grass skirt, tied over a ragged gown of cheap print, sat in front of a hut to our left. She gesticulated in a frenzied, incoherent manner, smiling and nodding her head at us. Prendergast greeted her in Rarotongan, calling her ‘Mama’ (Metuavainé). At this she gesticulated more frantically than ever, cackling like an old witch, but I noticed that her teeth were beautifully white.

‘It’s old Mama,’ Prendergast explained; ‘she’s William’s wife, and a fine old lady she is, too!’

We shook hands with her. The hand-shaking ceremony is still fairly recent at Puka-Puka. Formerly the islanders rubbed noses and sniffed in true native style, but the Revd Johns, the missionary who visits the island every year or two, had taught them the white man’s manner of greeting.

While we were talking with Mama, Kare Moana, or Sea Foam, as the name is translated – I shall avoid native names in these memoirs when they can be rendered in English – appeared on the scene. He is one of the few Puka-Pukans who have visited other islands, and the only one, I think, who has ever seen foreign countries. He had passed through New Zealand and Australia on his way to Papua, where, in fever-stricken coastal lands, he did missionary work for which the white missionaries got all the credit. He was dressed in new denim trousers, a ‘boiled shirt’ with a celluloid collar and a funny little black necktie fastened askew. He wore a bandmaster cap decorated with gold braid. It was much too small for him and sat on the top of his round head in a supercilious manner, as though conscious of the fact that it was the only bandmaster cap on the island.

Sea Foam greeted us in Rarotongan, which he spoke fluently, although every few sentences he would change abruptly into old biblical Tahitian; and when he spoke of his house he always called it ‘my la maison’. This was the single French expression he had picked up at Tahiti. In the curious native fashion he asked me whether I were alive? hungry? thirsty? Did I wish to sleep? How many brothers did I have? How many sisters? How old were they? What was the colour of their eyes? their hair? etc., etc. When I had replied to his various questions he assured me that I was a fine fellow, by far the best white man who had ever landed at Puka-Puka. All this was in the Tahitian dialect. Then, in Rarotongan, he said that he would feed me as long as I stayed on the island. This was a thing any native would say, but Sea Foam to a large extent actually carried out his promise.

Turning, he shouted in an unfamiliar guttural tongue and immediately a small boy ran out of a hut, ‘walked’ up a coconut palm like a monkey on a stick and threw down some green drinking-nuts. He slid down, grabbed the nuts, husked them with his teeth and handed them to Prendergast and me. Then he vanished, doubtless to sleep again. His little act was performed as quickly and beautifully as a conjurer’s trick.

After our drink, Prendergast talked business with Sea Foam.

‘Kare, Viggo says that since you an’ ’im is old cronies, ’e’s goin’ to do you a favour by rentin’ your coral-lime ’ouse. ’E’s goin’ to give you a quid a month.’

Sea Foam’s face displayed neither pleasure nor displeasure. ‘Ah, yes,’ he said gravely. ‘My fine new la maison. There are two storeys and a floor of real boards for the upper storey. It has the finest thatch roof on the island.’

‘Never mind about that. We know what a blinkin’ fine ’ouse it is, an’ ’ow it gets the ague every time the wind blows. You’re satisfied, are you – a quid a month?’

‘Ah, well, Viggo and I are as brothers. I should be ashamed to refuse him anything, so you can tell him I will let him have my la maison for two pounds a month.’

‘Two wot? See ’ere, Kare! Viggo said I was to arsk Ura and Rori in case you wouldn’t be sensible about that old shack of yours. Two pounds! Strike me bleedin’ well pink! It ain’t worth ten bob!’ The supercargo winked foxily at me.

Sea Foam stroked his chin thoughtfully.

‘Ah, well,’ he said, ‘you’d better speak to Rori or Ura, then. Now about our copra: we won’t be able to load the schooner this week or next week either. We are having a church festival and the Reverend Johns would never forgive me if we worked during the festival.’

Prendergast pulled a long face. ‘Oh, have it your own way, Kare. We ain’t partin’ brass rags about a blitherin’ quid. We’ll pay you two quid for yer fine new la maison. Now, then, ’ow about the church festival? You ain’t goin’ to ’old up the ship for any jamboree like that, are you?’

‘Oh, mercy, no!’ said Sea Foam in his soft voice. ‘The Reverend Johns would never forgive me if I kept Captain Viggo waiting.’

An hour later I passed through the central village where the trading station was to be and, turning into a path which led behind the great coral-and-thatch church, walked through a desolate graveyard and on to the coconut groves and taro-beds of the interior. It had been long since I had stretched my legs, so I took advantage of Prendergast’s good nature, leaving him to check over the trade goods Viggo was sending ashore.

Inland, as much as fifty acres had been excavated to a depth of ten feet, bringing the taro-beds to sea level, where the roots of the plants could flourish in swampy ground. This work must have required many years to complete, for there were no tools but coconut shells with which to scoop out the sand. In these beds puraka and bananas also thrived, making one forget that Puka-Puka is an atoll.

While skirting the first taro excavation I heard a cry from the village: ‘Paji! Paji!’ The word is sufficiently like the Rarotongan one for ship to inform me that at last the inhabitants were waking to the fact that Viggo had come. Looking back, I saw that the sleepy little village was now astir. Fathers and mothers were stumbling out into the blazing sunlight and funny little naked children were running back and forth in great excitement.

I wandered on, past a dozen or more taro-beds and as many desolate little graveyards isolated among the groves. The island is dotted with these burying-grounds, for the graves of the discoverers of the island and all their descendants are still intact. They are weird places, with headstones of coral slabs covered with innumerable designs. The enclosures are bare of vegetation; they gulp the hot sunlight voraciously and give it back in scorching waves of heat. Later I heard many remarkable stories about these graveyards: the entire history of the island may be read there, and the shape of each stone is distinctive, relating the story of the individual buried beneath.

Near the sea side of the islet the taro-beds give place to coconut groves, for here the sand has been banked from twenty to thirty feet high. Trees with gale-gnarled limbs grow by the beach, sheltering the palms, and beyond is scraggly bush which gains meagre sustenance from the coral gravel thrown up by the sea.

On breaking my way through the bush I closed my eyes before the glare of exposed sand and the shallow water between the reef and the shore, reflecting the full blaze of the sun like countless mirrors. The shallows were alive with cross-seas meeting in sparkling ridges of spray, falling back in dancing undulations. Miniature waves washed up on the beach, which gulped them down, leaving no backwash; and from farther out came the incessant thundering of the great Pacific combers as they rose high to crash in resounding cannonades along the reef and to spill back into the sea, exposing rust-red ridges of coral broken by pools of sea foam.

I came to a point of the islet where, beyond the reef, seas from both north and south swing round the land to meet with tremendous impact. That morning I could enjoy watching these great seas wrecking each other, but later, after I had been washed over the reef in the midst of a gale, I could not pass this point of Teauma without a shudder.

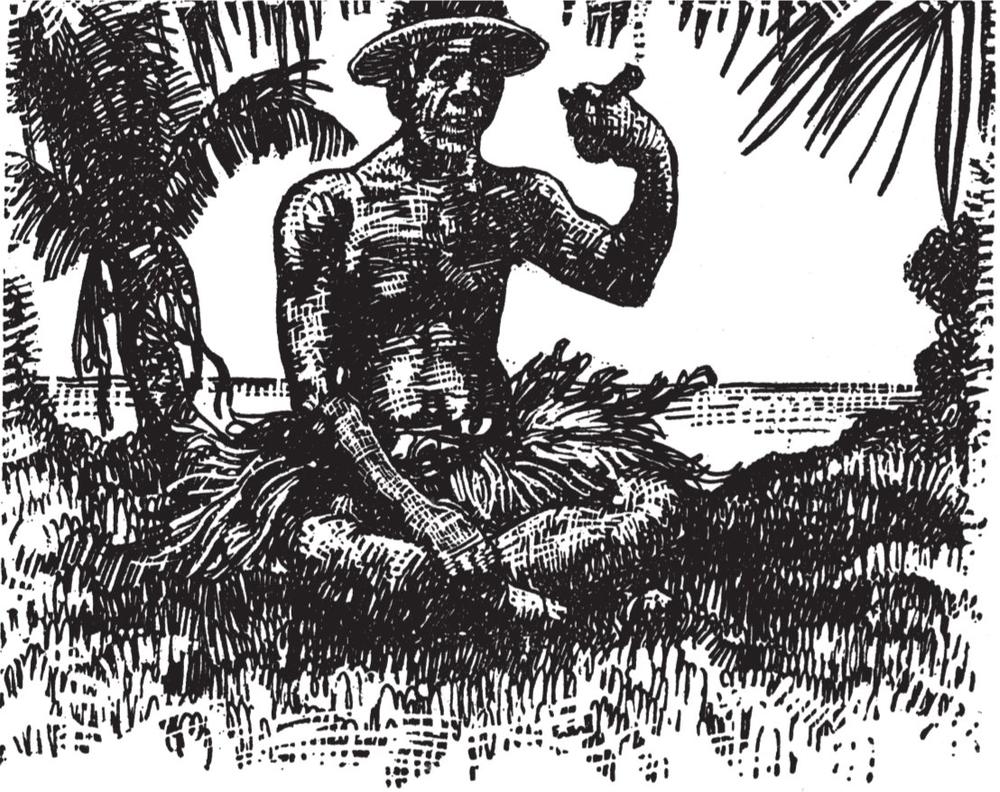

‘Ulekaina!’ croaked a froglike voice, so close at hand that I was slightly startled. I looked about, but at first saw no one. Then, to one side, I observed a mound of coconut leaves somewhat resembling a small hayrick. A grizzled brown head protruded from the top of it, and a face furrowed all over with deep wrinkles. On the head was the brim of a European straw hat; the crown was missing; the head thus framed was shaped as nearly like a blunt-nosed bullet as a cast could have made it. Under the brim a pair of small shrewd eyes regarded me closely, and a pair of ears, anything but small, stood out almost at right angles from the head. The skin of the face was like old, well-seasoned shoe leather, pierced on the chin by about a dozen wiry hairs that served as a beard.

‘Ulekaina!’ the voice again croaked, and of a sudden the hayrick rose and became an enormous grass skirt which covered the old man at least a foot deep. He raised a long index-finger, described a circle in the air, and then pointed at himself. ‘Uiliamu’ (William), he said.

I described a similar circle with my index-finger, pointed to my breastbone and said, ‘Ropati.’

He nodded in a knowing manner, resumed his hayrick posture, and produced a pipe from somewhere in his grass skirt. Holding it to within an inch of his right eye, he stared into the empty bowl and sighed deeply. Then he brought forth an empty tin, gazed into it in the same distressing manner, and demonstrated its emptiness by turning it upside down and shaking it vigorously. I handed him my tobacco tin, whereupon he proceeded to fill his own in the good old Scots fashion, cramming the tobacco down, making far-sighted provision for the future. Having filled his tin, he again concealed it in the grass skirt and, digging into another part of the hayrick, produced a stick of tobacco and some dried pandanus leaf. With these he rolled two cigarettes, one for me, in consideration of my generosity. We smoked them in silence.

After a long and, to me, rather embarrassing interval, he said, in polished whaler English: ‘Where ta hell you from?’

‘What?’ I said. I was rather bowled over by this sudden question.

‘Goddam! You no spik English? What ta hell! You Daggo? You Chow? I spik too much English. Whas a matter you?’

‘I’m an American,’ I said. ‘I’ve come here to open a trading station. Where did you learn English?’

‘Me? What the devil! Me whaler-man! Me no Puka-Puka Kanaka! Whaler-man! Tutae-auri!’

‘Tutae-auri’ means ‘heathen’, and William went on to assure me that he had nothing to do with Christians. This interested me, for very few of the natives on these lonely islands have the courage to flout the missionaries. Although few or none of them have more than a vague notion of what Christianity is about, nevertheless they are great churchgoers. I have not met more than three who, like old William, were avowedly and boastfully heathen.

We sat for a long time on Teauma Point, yarning about all sorts of things. Once he left me for a moment to shin up a coconut palm for drinking-nuts, as agilely as though he had temporarily shouldered off half a century. We talked until noon, when he accompanied me to the village, going before me with an air of possessorship, for he told me that he meant to adopt me as his son, exhibiting me to all the Christians as the white man whose Godlessness was equal to his own.