AT THE TIME OF VIGGO’s first return to Puka-Puka, while rummaging among the ship’s stores for some delicacies to take ashore, I discovered a considerable stock of malt extracts and hops, some packages of raisins and several jars of maple syrup. Not being altogether an ignoramus in the fine art of brewing, I took all of these articles that Viggo could spare. As a brewing receptacle was then required, Viggo, with his usual ability to furnish almost anything needed in the islands, sent ashore an old crockery water-cooler of eight gallons’ content, and a five-gallon demijohn.

For many months thereafter I experimented in home brews, and the more I concocted, the more convinced I became that the simpler the brew the better. I finally adopted the following recipe:

¾ pound of hops boiled in seven gallons of water

5 pounds of washed rice

6 pounds of brown sugar

1¼ pounds of malt extract

1 tablespoon of salt.

When the hops water has cooled, it is strained into the eight-gallon crock and the other ingredients added. When making the first brew it is a good plan to add a little yeast, but this is not important except in cold weather. When the brewing has entirely ceased and all the sediment has precipitated, leaving a clear fluid with a mouldy scum on top, the ale is dipped out carefully so as not to stir up the sediment, and strained into another receptacle, where a half-pound of sugar is added. Then it is bottled, preferably in crown-cap bottles, for if others are used great care must be taken in fastening down the corks.

One soon learns that the less sediment, the better the brew. When I wish a specially fine brew I pour the ale directly from the barrel into a demijohn, allow it to stand for about a week until a perfectly clear fluid is obtained, then drain it carefully into another receptacle, add the sugar – a half-pound to eight gallons – and bottle.

In making the second brew the same rice is used over again, with an additional half-pound of new rice. In fact, the rice should never be thrown away, for the longer it is used, the better the ale. In the first brews it imparts a slightly raw taste, but in the fourth or fifth brews this disappears and one has a perfect beverage. In making my brews I wash the rice after every other brew, so as to eliminate a part of the sediment. There is, however, a diversity of opinion on this matter among contemporary atoll brewers. One gifted artist on Rarotonga never washes his old rice, while another, on the island of Mangaia, washes his thoroughly after every brew. The Rarotonga artist’s ale has a fine flavor but is somewhat cloudy; and while the Mangaia brewer’s ale is as clear as the fountain of Arethusa, it often has a raw taste due to the necessity of adding at least a pound of new rice to each brew to make up for the coarse sediment and broken rice lost in the process of washing. Therefore, I adhere to my middle course of washing the rice after every other brew.

Of course, one is greatly tempted to consume the brew during the first week or two after it is finished, but one should exert the utmost self-restraint and leave it for six weeks, when it is at its prime in this climate (probably a longer time is needed in cooler latitudes). At the end of this time he will have six brews of forty bottles each, that is, provided he brews steadily. He may then enjoy forty bottles of mature ale each week, which is just enough to keep one in good health. In my own case, I keep two or three brews going at once so that I have from eighty to one hundred and twenty bottles a week – none too generous a supply, for I find that I have more friends now than I did during the earlier dry season.

I used the raisins and maple syrup for wine. It is made as follows: Crush five pounds of raisins and pour them into a five-gallon demijohn; add three pounds of washed rice, six of brown sugar, and one pound of maple syrup or honey. Then fill the demijohn with water that has been boiled and allowed to cool. If hot water is poured in, the wine will not ferment. Fermentation is completed in from twenty-five to thirty days, depending on the temperature. During this time the demijohn is closed with three thicknesses of calico tied over the mouth. When fermentation has stopped, the wine is bottled and corked lightly. At the end of a week or two it is carefully decanted into new bottles. Thus clear wine is obtained. It is now corked tightly and the bottles are stored, lying on their sides, for at least three months. A year is better, and some of my wine, now three or four years old, is really excellent. But new raisin wine is nauseating stuff, with a vinegary flavor and ruinous to the digestion.

For some time before my first brew was ready I had been suffering from digestive complaints, malnutrition, and general debility due to the enervating nature of the climate. A so-called perfect climate, like that of Puka-Puka, where the temperature never drops below 70 nor rises above 85, often proves injurious to one’s general health. Without cooler weather one’s system becomes sluggish and unable to resist disorders that would hardly be noticed in a more severe climate. But when my first brew was six weeks old, Benny and I made it a daily habit to empty five or six bottles, whereupon I quickly recovered my health, could eat anything and digest it, too, and found my system generally toned up in a remarkable degree.

As my ale became known on the island, the Puka-Pukans began to develop various internal complaints for which my home-brew was the only possible remedy. They would appear at the trading station at 8 p.m. sharp with such regularity and precision that I could set the store clock by their appearance. They made their headquarters in the back room of the station, where the bottles were stored. My most regular visitors were Ura, chief of police; Husks, the policeman from Central Village; Benny, and Pain-in-the-Head (Upoku-Mamao), an Aitutaki native who had been captivated by Puka-Puka indolence and one of the island maidens. Sometimes Wail-of-Woe’s father, Breadfruit, dragged his elephantiasis legs into the back room to partake of a few glasses to relieve the filarial fever; and often dear old rheumy-eyed Bones came in with his pig and his mouth organ to sit cross-legged, fondly gazing at the store of bottled refreshment stacked along the wall. Despite his depravity, I have a sort of liking for old Bones, and I could always get rid of him by saying that I had just seen a bevy of damsels making their way to the lonely outer beach.

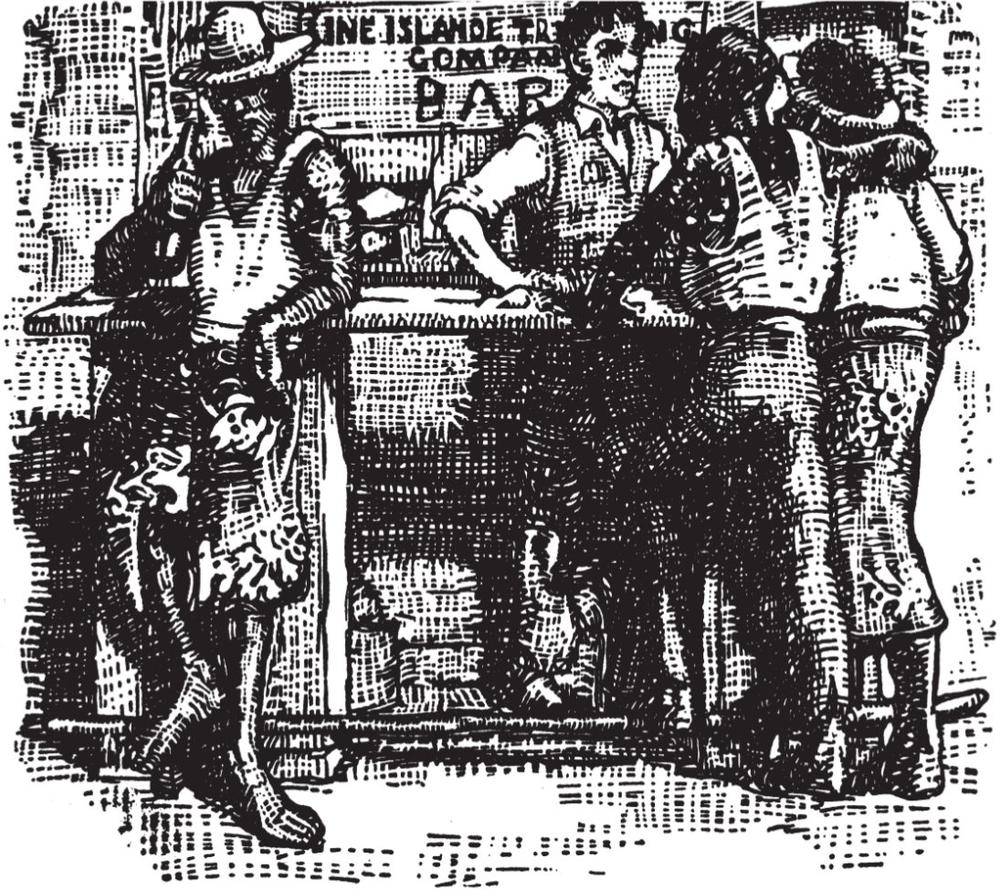

After a few months of brewing it occurred to me that since I now had ‘jolly good ale and old’, and excellent wine too, I might as well have a bar to drink it over. So I laid a couple of boards across two boxes and built some shelves, the back of which I decorated with corked empty bottles: Black and White, Dubonnet, Peach Brandy, Crême de Menthe, St James Rum, etc., as well as a few tins of Vienna sausage and Rex cheese. A bottle of pickles, cigars, some tins of cigarettes and some cartons of safety matches completed the picture. Then I made a conspicuous sign, proclaiming:

LINE ISLANDS TRADING COMPANY BAR

and hung it from a rafter. Then I stepped behind the bar and said to the imaginary customer on the other side: ‘What’ll it be, sir, beer? Puka-Puka Prize Ale?’ whereupon I stepped round to the other side and said, ‘Yes; not too much head on it, please,’ and, in lieu of a nickel, threw a sixpence on the counter. The first glass of ale ever served across a bar in the history of Puka-Puka was deliciously refreshing, and the bartender, with old-time American hospitality, served me with a tasty snack to enjoy with the beer: sausage, bread and pickles. Afterwards I smoked a cigar and offered one to the bartender, which he accepted and put in his waistcoat pocket.

At 8 p.m. Benny, Ura, Husks and Pain-in-the-Head awoke and came in for eye-openers. I put the chief of police behind the bar, instructed him in his duties, and we four convivial spirits sprawled along the counter drinking ale and telling yarns till cockcrow. It was that morning, I remember, that I started three brews going instead of one.