1

Getting Back in Sync

A $50 billion problem. Every year, millions of office workers in the United States develop serious injuries or health problems on the job. You’d think that an office job would be safer than factory work, but the truth is that most of these conditions are associated with our deskbound workstyle.

Back injuries are just one example, with direct medical costs that top $50 billion every year. Back problems are not simply an issue for workers doing physical labor. Currently, the people at greatest risk of injury are those with a desk job making over $70,000 annually. We’re just not designed to sit in front of a computer all day and a TV all night.

This matters. The data show that one in two adults will report a musculoskeletal condition uncomfortable enough to require medical attention. Similarly, one of every three office workers in the United States experiences back pain.

- Fifty-five million employees report recurring fatigue.

- Forty-five million have back injuries linked to computer use.

- Forty-five million workers suffer from tension headaches or carpal tunnel syndrome.

More than 30 percent of North Americans who work at a computer develop a muscle strain injury in any given year. In Japan and the Middle East, similar rates of injury have been reported. Globally, computer-related disorders continue to be on the rise.

These conditions can affect anyone who spends long hours at a computer. In a large survey of high school students, 85 percent experienced tension or pain in their neck, shoulders, back, or wrists after working at the computer. Additionally, the longer they spent on social media or binge-watching, the greater their risk of depression.

How We Know What We Know

For the past twenty years, teams of researchers all over the world have been evaluating workplace stress and computer injuries—and how to prevent them. As researchers in the fields of holistic health and ergonomics, we observe how people interact with technology. What makes our work unique is that we assess employees not only by interviewing them and observing their behaviors, but also by monitoring their actual physical responses.

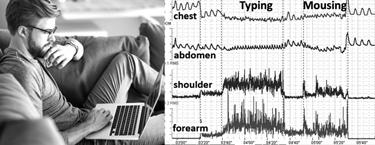

That means measuring muscle tension and breathing, in the moment, in real-time, while they work. To record shoulder pain, for example, we place small sensors over different muscles and painlessly measure the muscle tension using an EMG (electromyograph), a device that is employed by physicians, physical therapists, and researchers. Using this device, we can also keep a record of their responses and compare their reactions after we have them change the way they work.

The EMG enables us to graph and visually describe how a participant’s muscles react as they perform various tasks at the computer. We can see on the screen, second by second, how people are responding. When a muscle isn’t being used, the level of tension registers as zero. Then we measure how much the muscle is tightened and how long it is held in tension.

What we’ve learned is that people get into trouble if their muscles are held in tension for too long. Working at a computer, especially at a stationary desk or workstation, most people maintain a low level of chronic tension for much of the day. Shallow, rapid breathing is also typical of fine motor tasks that require concentration, like data entry (see figure 1.1). When these patterns are paired with psychological pressure due to office politics or job insecurity, the level of tension and the risk of fatigue, inflammation, pain, or injury increase. In most cases, people are totally unaware of the role that tension plays in injury.

Figure 1-1 Muscle tension and breathing rate usually increase during data entry or typing without our awareness.

How much is too much? These reactions differ from one person to the next. Some people have many quick-firing muscles, and others have muscles that react slowly. This is another factor in who gets injured and who doesn’t. As consultants, often we can predict who is most likely to develop an injury just by measuring their shoulder muscle tension. The absolute level of tension does not predict injury—rather, it is the absence of periodic little rest breaks (relaxation breaks) throughout the day that seems to correlate with future injuries. You can get a sense of how quickly tension builds up with the following exercise.

We would like to provide a snapshot of what we’ve observed in our work and what we think is going on:

- Good ergonomics are not enough. By studying the physical reactions of people with computer injuries, computer-related disorders, and workplace aches and pains, it became clear that just replacing the equipment was not enough. Improving the ergonomics was not sufficient. People were still getting injured, and many of those who got injured weren’t getting well. This observation raised questions about why simply applying ergonomic solutions often does not resolve the problem, and why we need more than ergonomics to solve workstyle injuries, conditions, and disorders.

- People are usually unaware of muscle tension until it hurts. When we monitor muscle tension, employees often tell us that their muscles are relaxed. However, as measured by the equipment, we find that their muscles are contracted and tight. This is similar to being unaware that your shoes or belt are too tight. Yet the moment you kick off your shoes or loosen your belt, you feel better.

- Sitting is the new smoking. Our bodies aren’t suited to the physical inactivity of the modern workplace. A quick look at human history shows why. The hunters and gatherers who roamed the earth for more than half a million years were very physically active. Today the majority of people live in urban settings. Many of us work in offices, and our jobs involve very little physical exertion. Yet we’re still genetically programmed like nomadic hunters and gatherers—our bodies and our reflexes are still hardwired for activity and physical exertion. (For more insight on this, see chapter 5.)

- Physical tension has side effects. When we’re not getting enough physical activity, tension builds up in our bodies that eventually affects our muscles and nerves. Over time, this tension can cause insomnia, fatigue, and eventually, chronic pain conditions.

- Mental stress is another cause of injury. We’ve found that stress and tension are major factors in these conditions—particularly in back and neck problems and repetitive strain injuries. Mental and emotional stress, like inactivity, can underlie chronic muscle tension and contribute to workplace injuries. In call centers, for example, when calls are monitored by a supervisor, those workers have a higher rate of muscle tension and eventual health issues compared to workers who can work more independently.

Once we realized that stress (both external and self-induced pressures) contribute to injury, we knew that we needed a more holistic approach to computer-related health issues and workplace burnout. In response, we developed a practical self-help program to reduce stress and prevent injury. The program is based on more than one hundred of our research studies in biofeedback, physiology, and body mechanics. At least twenty of these studies looked specifically at what happens to our bodies when we use a computer. We also drew on leading-edge research from around the world.

Health issues similar to those described in the sidebar are often problems that cannot be fixed with a single solution—neither ergonomics, nor exercise, nor stress management alone is enough to overcome the strain and drain of modern workstyle. We need to look at the problem from new, more holistic perspectives.

Figure 1-2 Even at the beach, we cannot leave the digital world behind. (Photo by Erik Peper)

The Caveman at the Computer

We began our research in 1996. The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, cracking the code on human genetics. Given what we know today about genetics, it’s clear that we need to evolve a healthier workstyle. Although our environment is changing at warp speed, our genetics have scarcely changed over the past half million years. Computers and similar technologies became an integral aspect of our workstyle less than forty years ago. The first smartphone—the iPhone—was just introduced in 2004.

Yet according to the Human Genome Project, we’re still genetically wired like the hunters and gatherers. We’re better suited for hunting and gathering than typing and clicking. Today we sit for hours at the keyboard and spend hours on the phone, texting, pecking away, moving just the muscles of our fingers instead of walking, climbing, reaching, digging, pounding, lifting, pushing, pulling, running, or swimming.

Today most of us spend more time with our phone and our computer than we do with our life partner or our best friend. We take our electronics with us everywhere, use them anytime, and typically can’t engage in work, play, shopping, or communication without them.

We rush to buy the latest technology, thrill at the latest breakthrough, are primed and ready to adopt the next-new-thing to do more, faster, and better than last year’s tech. We put up with all kinds of aches and pains without giving them a second thought, just to stay in the game. Using the latest gadgets, many of us become stoic sufferers, sore and tired. Note that four of the top health complaints people take to their family doctor—fatigue, tension headaches, back pain, and repetitive strain—can be caused by long hours on the phone or at the computer.

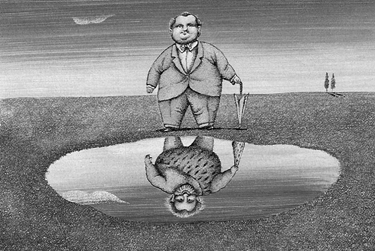

Figure 1-3 Despite a modern appearance, we carry the genes of our forebears—for better and for worse. (Art courtesy of Peter Sis)

Even our eye muscles are getting out of shape! Instead of scanning the horizon for dangerous animals or searching for food, we stare at a screen for hours on end. Our bodies are built to move, so modern workstyle is vastly out of sync with our genes. As a result, many of us pay the price with anxiety, depression, insomnia, or chronic pain. In parts of the world where tech is prevalent, children now develop nearsightedness at a young age and often need to wear glasses. For context, nearsightedness is a condition that typically develops after age forty. We’re not designed to be glued to a screen morning, noon, and night, nor are we designed to text while we eat. We need to adapt—to develop new skills so we can survive the limits of our technology, our workplace, and lifestyle.

The Missing Manual for the Human Frame

Although every computer comes with volumes of detailed instructions on how to use the hardware and software, almost nothing is mentioned about how to develop a healthy, productive, and creative work environment. Companies spend billions on equipment and training, yet often little is spent to prevent injury.

Ready for a change? You’ll find useful strategies, work-arounds, and hacks for work and life. Enjoy!