FEEDING YOUR CHICKENS

Chickens, like people, need a variety of nutrients in order to remain healthy. And, like people, they suffer serious nutritional disorders if certain constituents—including minute quantities of specific trace minerals—are missing from their diets. Also, their dietary needs change with age. Growing chicks have quite different needs than mature laying hens.

COMMERCIAL RATIONS

Commercially prepared chicken rations are designed to provide a perfectly balanced diet for each type of flock. A complete line of special-purpose chicken feeds, including formulations for baby chicks, growing fryers, growing pullets, layers, and breeders is available in many feed stores. Information on them may be found on the websites of major feed suppliers. The simplest feeding program, and the best option for the beginning backyard chicken-keeper, is to feed the flock the special-purpose feed that is designed to meet their needs.

Some feed suppliers offer a limited number of all-purpose feeds, for example a starter ration for chicks and a layer ration for mature chickens. In such a case, feed the starter ration to chicks for the first 5 months, or until they start to lay eggs, then gradually switch over to the layer ration. Do not feed layer ration to chicks before they are ready to begin laying eggs. Layer ration is lower in the protein chicks need for growth and higher in the calcium hens need to produce eggs. Chicks fed layer ration won’t grow well and will suffer irreparable kidney damage.

Prepared feeds come in the form of mash, pellets, or crumbles. Mash consists of ground-up ingredients and looks something like cornmeal (but a different color). We find that both chicks and grown chickens tend to waste mash by spilling it on the ground and trampling it. Therefore, the pellet and crumble forms prove to be more economical.

Pellets are made by compressing mash into small tube-shaped pieces. Pellets are too large for baby chicks to eat but are ideal for mature chickens. Pellets come in a small size and a regular size, depending on the feed brand. We like the smaller size for bantams, and we also find that larger breeds spill less feed on the ground with the smaller pellets than when fed the larger size.

Crumbles are crushed-up pellets. Crumbles are best for baby chicks, with their small beaks. Some layer rations come as crumbles, but, again, we find that older chickens tend to waste more crumbles than they do pellets.

Rations are usually sold in bags weighing 25, 45, or 50 pounds, depending on the brand. Some feed stores will open a bag and sell feed by the pound.

Chicken feed is no longer cheap (even if it is still a metaphor for small-time financial doings), and when sold by the pound, the price can be outrageous. But feed does go stale and loses nutritional value. Purchase only as much as your chickens will eat within 2 to 3 weeks.

How much chickens eat depends on the season and the temperature (they eat more in cold weather than in hot weather), as well as their age, size, weight, health, and rate of egg-laying. We recommend keeping feed available to chickens at all times, a method called free-choice feeding, and let the chickens decide how much they need.

Incidentally, just because chickens get up at the crack of dawn doesn’t mean you have to get up that early to feed them. Some of our friends assume we must be early risers because we have chickens, and they consider themselves at liberty to phone us at uncivilized hours of the early morning. But we just make sure some feed is out at sundown so the chickens can eat breakfast while we’re still in bed.

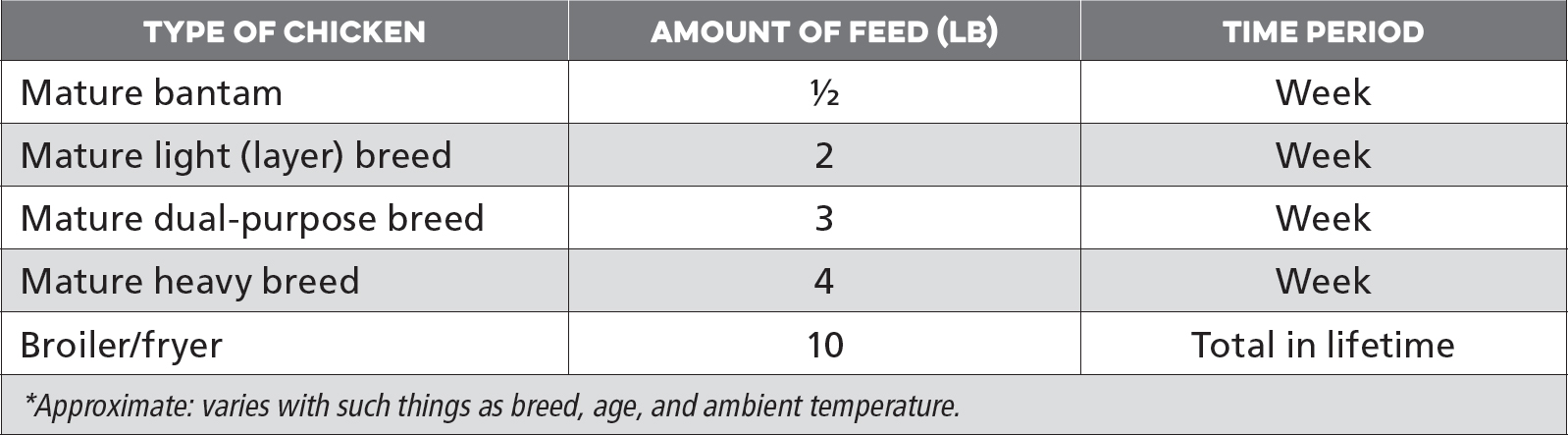

HOW MUCH CHICKENS EAT*

SCRATCH GRAIN

The old-favorite chicken feed called scratch consists of various whole grains mixed with cracked corn. It’s called scratch because, when it’s tossed on the ground, chickens come scrambling to scratch the ground, while gobbling down the grain. Scratch has been an old farm standby since time immemorial. But, it is not a complete dietary ration and makes an unsatisfactory permanent menu. That would be the equivalent of a human diet of doughnuts for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Scratch mixtures consisting largely of corn are not recommended. Some corn is fine, but as grains go, corn is lower in protein and higher in fat, and tends to make chickens obese. A plump bird is, of course, highly desirable. Plumpness results from full fleshing and is an excellent indicator of sparkling good health. But an obese hen doesn’t lay well, and an obese fryer on the dinner table is unappetizing.

Scratch does have good uses. In cold weather, sending chickens to roost with a cropful of grain will help them stay warm, as the grain digests throughout the night. And, tossing a bit of scratch into the coop at sundown encourages reticent chickens to go inside, rather than spend the night in a tree or on the coop roof. Otherwise, think of scratch as a type of candy, and consider it to be no more than an occasional treat for your chickens.

NITTY-GRITTY ON GRIT

Chickens that are fed anything other than commercial poultry rations must have access to grit for their digestive systems to function properly. Since chickens do not have teeth, the masticating function is performed by their gizzards. The gizzard employs grit as a grinding agent. The grit may be simply pebbles and other small, hard indigestible objects the chickens happen to eat. Oh, and by the way, the reason chickens that eat only commercial feed don’t need grit is that these prepared rations are sufficiently softened for digestion by the chickens’ own saliva.

The grit itself gradually gets ground up, so it must be continually renewed. If chickens have a large outdoor area in which to roam, they usually get a sufficient supply of natural grit. For confined chickens, however, commercially prepared granite grit, which can be purchased at any feed store, will be necessary. Make a container of it available to your chickens at all times, so they can use as much as they need.

Another type of grit is calcium grit, usually in the form of crushed oyster shell. Laying hens need plenty of calcium to keep their eggshells nice and thick. A diet exclusively of layer ration supposedly supplies a sufficient amount, but the best laying hens usually need more than the ration provides. Therefore, make oyster shell available to them, especially if you are finding eggs with shells that are so thin they crack easily or that feel rubbery. These signs may indicate a calcium deficiency, and thin shells may encourage your hens to engage in egg-eating.

A lot of chicken-keepers like to recycle calcium by saving up eggshells and feeding them back to their hens. The shells should be well-washed, dried in the sun or oven, and crushed. Feeding chickens broken half-shells could well turn them into egg-eaters, and it is a hard habit to break. Their own shells alone do not provide hens with sufficient calcium for consistent egg production. Like granite grit, calcium grit eventually gets ground up and digested, so it should be available at all times for your hens to eat at will.

FREE-RANGE FORAGING

If a large, vegetative area is available for your chickens to roam, they will find excellent, nourishing, and delicious food. Seeds and insects will provide them with protein, as well as some of the essential vitamins and trace minerals that are so vital to a chicken’s health. However, even on the best possible pasture, foraging chickens will obtain less than 5 percent of their daily nutrient requirements.

The amount of nutriment foraging can provide varies with the nature of the vegetation. The younger and more tender the shoots, the more protein they contain. Grass (from a lawn that has not been sprayed with toxins) are fine for chickens, since a lawn is generally mowed before the grass gets old and tough.

The older and tougher the vegetation, the more difficult it is to digest. Fibrous material can even become wadded up in a chicken’s crop, blocking passage to the rest of the digestive system, a serious condition known as crop impaction that can end in the bird’s death by starvation. Granny had a catchy phrase to remind us of the proper type of vegetation to pasture chickens on: “The better for basket weaving, the worse for chicken feeding.”

We plant kale around our coop to provide our chickens with greens throughout the winter. Kale is easy to grow and flourishes during mild winter months, providing a good supply of fresh greens that chickens love. Because the kale is planted near the coop, the chickens can help themselves. But we must protect the seedlings or the chickens will immediately eat the tender, young plants right to the ground. After the plants grow tall and develop thick stems, they are less likely to be destroyed.

Another good source of greens is sprouted grains. Chickens are particularly fond of sprouted oats. They also like salad scraps, weeds, and surplus or overripe fruit and vegetables from the garden, seeds and all. Cut larger fruits and vegetables in half or quarters, and be sure to sort out anything that has begun to rot, as it can make your chickens quite ill.

Like scratch, greens do not furnish a complete diet and should be fed in moderation. However, chickens love fresh greens, and pecking at growing forage, garden scraps, or sprouts gives them something to do to keep them out of mischief. Besides, as our neighbor keeps reminding us, our eggs taste “eggier” than the store-bought variety, and she really likes their rich, orangey yolks—a result of feeding the chickens fresh greens.

GROWING YOUR OWN FEED

Occasionally, we’re asked about the practicality of producing homegrown chicken feed for backyard flocks. We have found that the amount of feed that can be raised in a small plot is hardly worth the time and trouble needed to grow it, and the monetary savings are virtually nil.

In an effort to economize and to provide our flock with especially fine feeds, we have attempted to grow grains in our garden. Our first crop was what we thought was a large patch of corn. After we watered and cultivated the patch all summer, and cut and dried the cobs in the fall, much to our dismay, the chickens got into the stored corn without our consent and gobbled it all down within one short afternoon.

Another year, we tried growing a plot of oats. The crop grew well, with little trouble to us beyond occasional watering. But, after the harvest, we found that the minute amount of grain we were able to recover was not sufficient compensation for the effort involved and for occupying a significant portion of our garden for an entire summer. Growing a substantial supply of chicken feed in a small area is simply not practical.

MIXING YOUR OWN RATIONS

Similarly, for the beginning chicken-keeper, mixing your own rations from purchased feedstuffs is equally impractical. For one thing, different types of chickens have different dietary needs. For another, all chickens have complex nutritional requirements. Too many novice flock-owners harm their chickens by attempting to mix their own feed, or by diluting a complete ration with all sorts of bizarre supplements that have been recommended by chicken-keeping friends or self-styled poultry gurus.

One of the biggest issues regarding home-mixed rations is providing adequate vitamins and trace minerals. Yes, vitamin and mineral premixes designed for chickens are readily available, but usually only in larger amounts than the average backyard flock-owner could possibly use within the premix’s 6-month maximum shelf life. Using an outdated mix can result in serious deficiencies and sick or dead chickens.

As a beginning chicken-keeper, don’t complicate things. And, don’t play Russian roulette with your chickens’ health by feeding recipes posted online by people who most likely don’t have the first clue about poultry nutrition. Find a brand of commercial ration that works well for your chickens, and make that the primary source of nutrients for your flock.

FEEDING FACILITIES

Feed should be stored in tightly covered containers. Depending on how much feed you purchase at a time, you might store it in a 5-gallon bucket with a lid or in a clean container designed for collecting garbage. The container will protect the feed from both rodents and moisture. Moldy feed should never be given to chickens, as it can make them seriously ill.

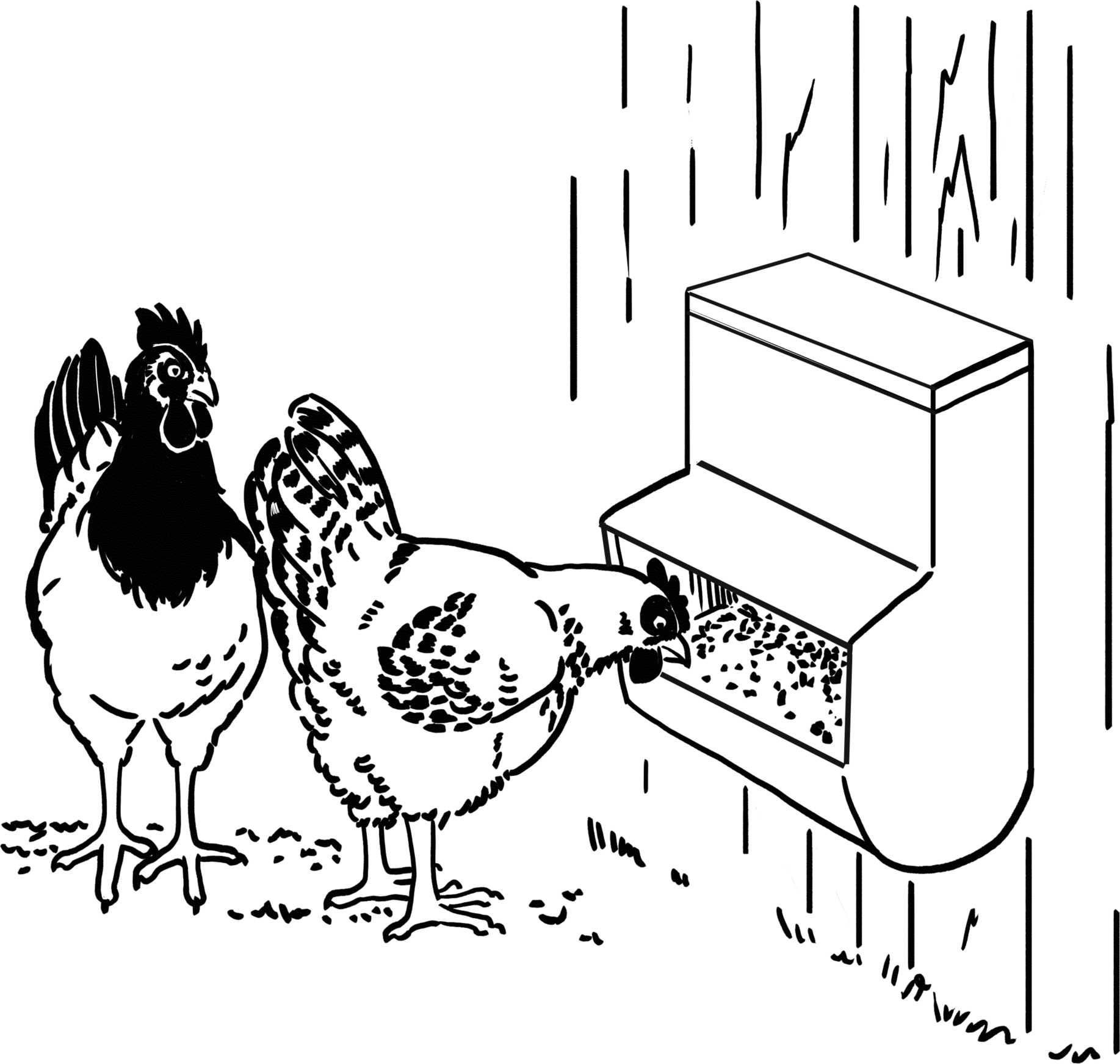

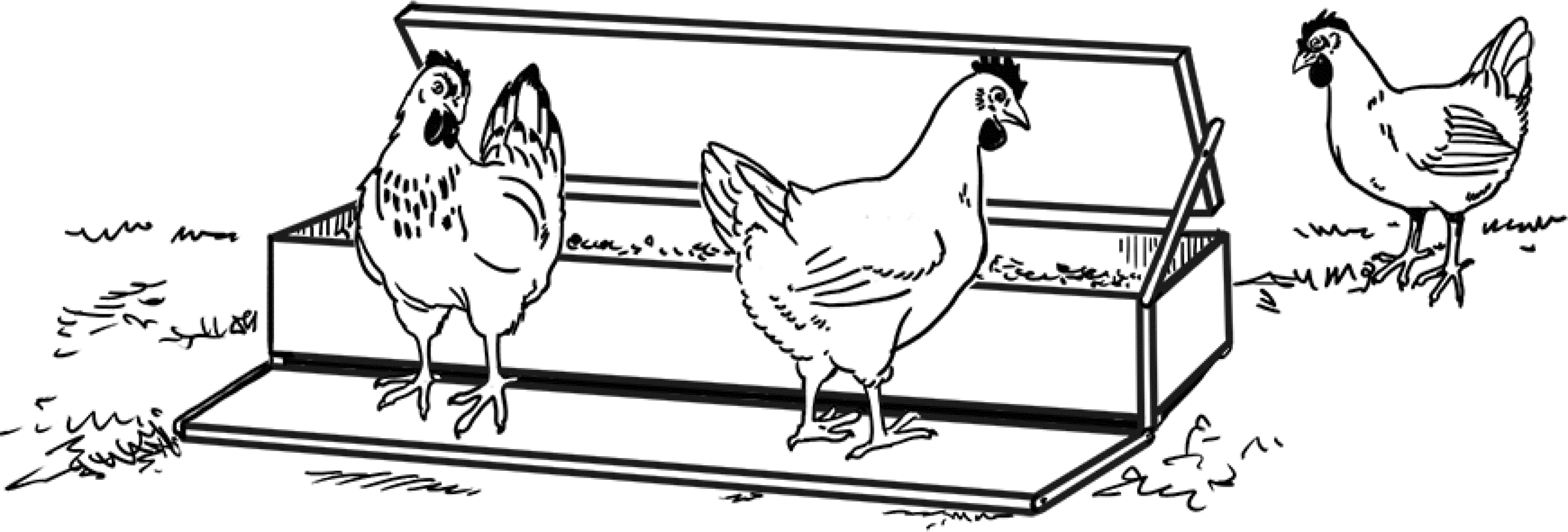

Using feeders is more sanitary than tossing the feed on the ground where the chickens walk and poop. Many different types of feeders are available from feed stores and online. Each style has proponents and detractors. Options include troughs that attach to a wall, freestanding troughs, hanging feeders, treadle feeders, rain-protected range feeders, and more. As chicken-keeping becomes ever more popular, new feeder styles are invented every day. The style that works best for you will depend on the size and number of your chickens, the space available for a feeder, and whether you plan to install the feeder inside or outside the coop.

A treadle feeder is a popular option

Features to watch for are, first of all, ease of cleaning. A feeder should be emptied and cleaned at least once a week. The easier this task is accomplished, the more likely you will be inclined to do it.

Another important feature is a method to keep chickens from roosting over, and pooping in, the feed, as well as stepping or scratching in the feed, or taking dust baths in it. Some feeders have either a wire guard or a cover designed to discourage roosting. Another option is to use a narrow feeder attached directly to the wall, which won’t give the chickens enough room for roosting.

Yet another important feature is one that prevents chickens from flicking feed onto the ground with their beaks, a habit called beaking out. Feed that’s been beaked out is rarely eaten, but instead gets trampled and pooped on and can attract rodents. A rolled-in lip on a trough feeder will discourage beaking out, as will filling the trough only half full. A style of feeder that requires chickens to poke their heads inside the feeder also prevents beaking out.

If you plan to install your feeder outside the coop, it should have a cover to keep out rain. It should also have a method for making the feed unavailable to rodents and poultry predators during the night. If nothing else, bring the feeder indoors at night and return it to the yard in the morning. Wild birds, and especially pigeons, may be attracted to an outdoor feeder, and their pilfering can significantly up your feed bill. The solution to this problem is to keep the feeder in a covered run.

FRESH WATER IS ESSENTIAL

Plenty of fresh, clean water must be available to chickens at all times. This essential aspect of poultry nutrition cannot be overemphasized. A large chicken will drink between 1 and 2 cups of water a day, depending on the weather. A chicken cannot drink much at once, so it must drink often, and it will do so where water is readily available.

Chickens must have water to be able to digest their feed. A chicken is more than 50 percent water, and eggs are 65 percent water. A hen that doesn’t get enough water cannot lay well. Even if she is deprived of water for only a short time, her laying may be seriously impaired.

Puddles of stagnant water from rain or leaky drinkers should be eliminated so the chickens won’t drink from them. Puddles become fouled by the chickens’ excrement, making them an ideal breeding medium for harmful bacteria and other disease-causing organisms. Chickens are not at all choosey about where they get their drinks. In fact, even when fresh clean water is available, they’ll still gravitate toward puddles. The quality of their drinking water is therefore only as good as the poorest water available.

As with feeders, a wide array of drinkers is available, ranging from bell-shaped waterers and automatically filling water bowls to nipples attached to water pipes or buckets. In selecting a style, consider the climate and whether or not the same type of drinker may be used year-round. You might opt to use one style in summer and a different style in winter, when the weather freezes. Or you might get an extra waterer, so you can bring the frozen one inside to thaw, while the chickens are using the other one. Or you might consider getting a drinker with a built-in heater for winter use.

Plastic versus metal is a consideration when purchasing a bell waterer. Both materials have poultry-keeping proponents. Galvanized metal drinkers are more durable than most plastic ones, and they resist deterioration by sunlight, but they can rust fairly rapidly. Plastic won’t rust, and it’s noncorrosive, but it is more likely to crack if the water freezes. Plastic is also more susceptible to getting moldy and accumulating algae; therefore it requires more frequent cleaning.

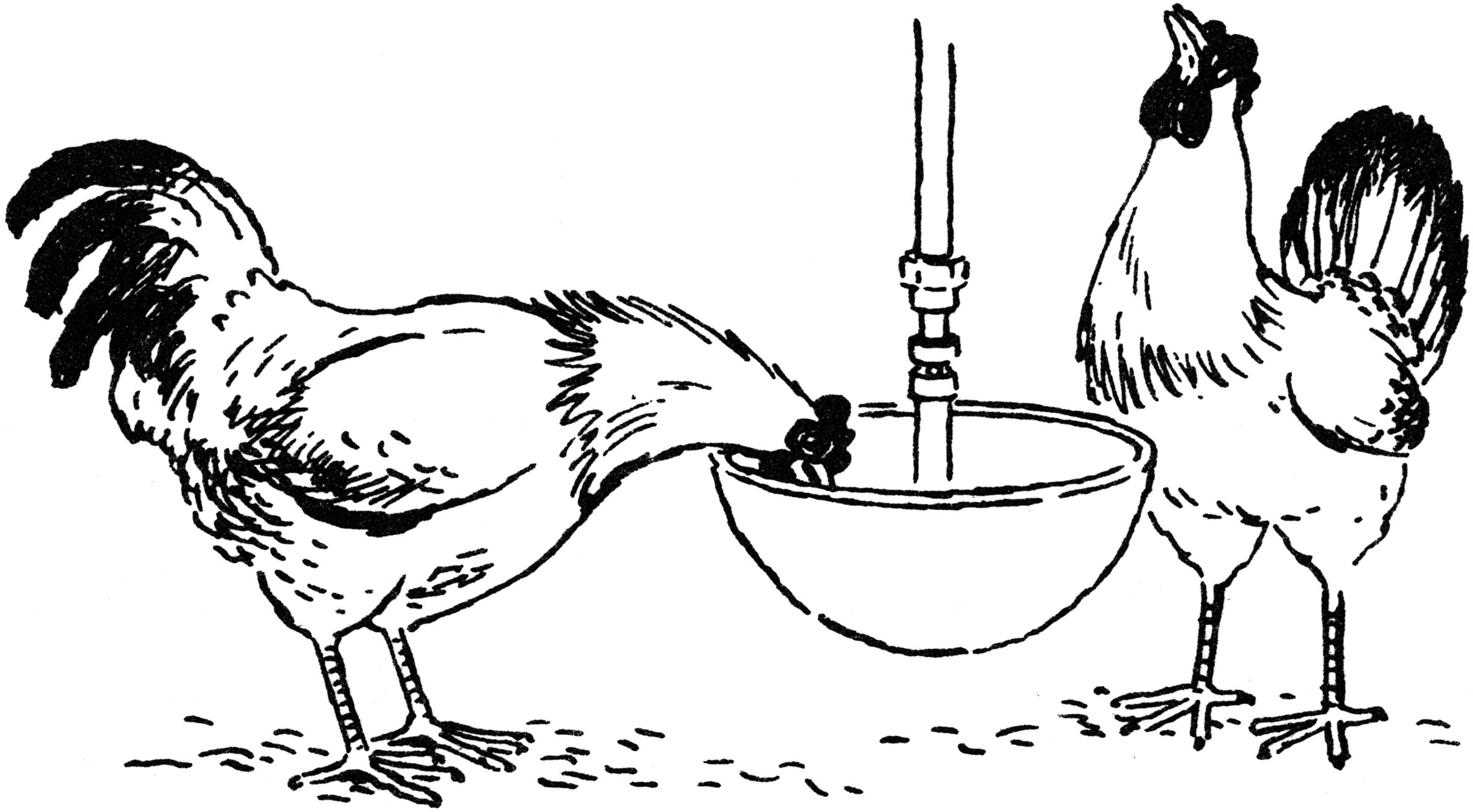

One type of automatic waterer

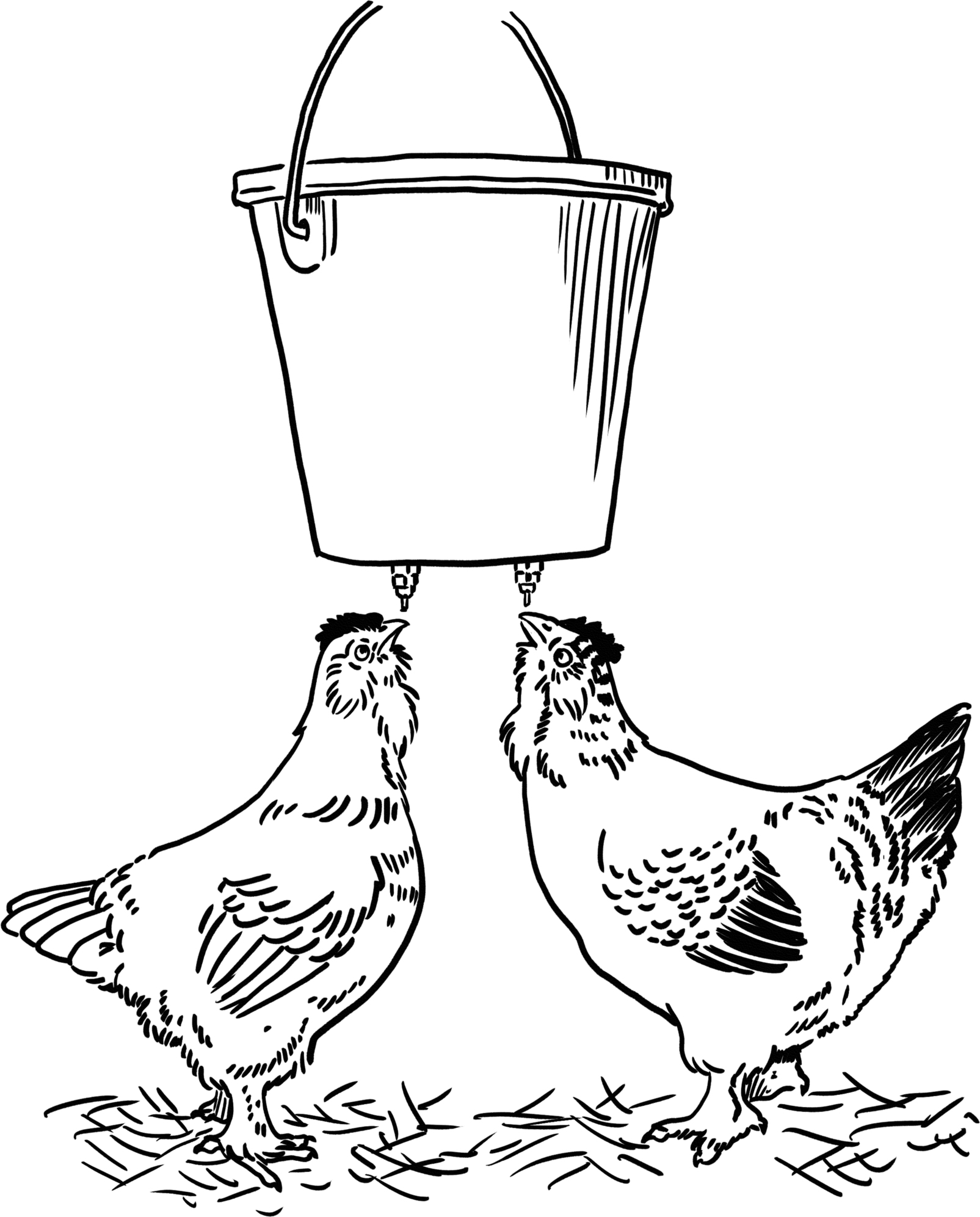

Homemade nipple drinker

In choosing a bell waterer, select a style that won’t tip over easily; otherwise, the water must be replaced frequently, and a wet floor provides a good culture for disease-causing organisms.

Living in a mild climate, where freezing weather is rare, we equipped our coop with automatic watering devices. They are easy to install on accessible faucets or with a length of inexpensive plastic pipe. You could also use a length of hose, if you get the type intended for potable drinking water. Once the waterers are installed, they are easy to maintain, if you clean them regularly to prevent algae from growing and remove any bugs or bits of dirt that have slowed the flow.

Many chicken-keepers today use nipple drinkers, which may be installed directly on a water pipe as an automatic device, or may be attached to a bucket or other container that is periodically refilled. Properly installed nipples don’t leak or need constant scrubbing to keep them clean. You just have to check them daily, by tapping each with a finger, to make sure it isn’t clogged.

Having chickens is no fun if their maintenance becomes an unpleasant chore. The amount of daily care chickens require, however, is minimal if you get properly set up and work out a daily routine of feeding and watering. Using feed and water equipment that best suits your climate and your flock’s needs will go a long way toward simplifying your daily chores and giving you more time to enjoy the company of your healthy, contented flock.