In an early treatise, written about 135 BC, we read:

Earth has its place in the centre and is the rich soil of Heaven. Earth is Heaven's thighs and arms, its virtue so prolific, so lovely to view, that it cannot be told at one time of telling. In fact Earth is what brings these Five Elements and Four Seasons all together. Metal, wood, water and fire each have their offices, yet if they did not rely on Earth in the centre, they would all collapse. In similar fashion there is a reliance of sourness, saltiness, bitterness and sweetness. Without that basic tastiness the others could not achieve ‘flavour.’ The sweet [the edible] is the root of the Five Elements, and its ch'i is their unifying principle, just as the existence of sweetness among the five tastes cannot but make them what they are.

This shows clearly the difference between the doctrine of the Elements in the East and West. The Earth, which is only one of the four elements in western tradition, is, in China, the central and most important on which all the others depend and from which they derive their vital energy (ch'i). The western teaching, following Aristotle and Empedocles, has four elements: earth, air, fire and water. For Aristotle, they proceed from the prima materia, a basic matter on which all forms can be imposed or imprinted, though itself remaining changeless. Matter and form interact to produce the four elements, which give rise to all things by simply changing the proportions of the elements, so that any one substance can be changed into another by varying the contents of the different parts, provided the right proportions are discovered. All things are, therefore, interchangeable: they are different forms of the same matter. This is the very essence of alchemical belief and work: that transmutation from one state to another is possible, that the principle of transmutation is inherent in Nature, so that the lead of base metal can be transformed into the purity of gold and the lead of the human situation transmuted into the gold of divine perfection. Or, as Marco Pallis phrases it: ‘It implies the possibility of converting whatever is base and polluted into something pure and noble.’ So, then, the Five Elements were not only concerned with material and seasonal changes but with the understanding of inner changes and alchemical transmutation in the individual.

There is, however, a suggestion of the fifth element in Aristotle's ether; while in the Hermetic and Rosicrucian teachings the four elements are represented by the cross, with the point of intersection, the centre, as the quintessence. A. K. Coomaraswamy draws attention to the idea of the four elements as demonstrating one of the many associations between alchemy, masonry and architecture. The four elements are symbolized by the four cornerstones, or foundation stones of a building, ‘since it is upon them that the whole corporeal world, represented by the shape of the square, is constructed . . . in fact there are not only the four basic elements, but also a fifth element or the “quintessence,” that is to say the ether, this latter is not on the same level as the others, for it is not simply as a base, as they are, but indeed the principle itself of the world.’ Here we have the fifth element taking on much of the same importance as the Earth in Chinese symbolism, except that in the latter the Earth is also a base. In Buddhist architecture the stupa takes the form of the five elements, the square at the base is the Earth, the union of the other four elements, with the circle as the waters, the triangle as fire, the crescent as air and ether represented by the jewel at the top. The symbolism of the stupa form of the elements, which marked sacred places or tombs, was that the dead have been re-absorbed into their original elements.

The Five Elements in Stupa form

The Five Elements of Chinese tradition, first propounded systematically by Tsou Yen, about 350 BC, were believed to be that from which all forms were derived. From this it followed that the body and its organs also proceed from those five forms, each associated with its particular element. The Five Elements and their properties are:

WOOD. East. Spring. Vitality. Production. The solid but workable. Sour. Blue or green. Controls liver and gall. The Dragon. Jupiter.

FIRE. South. Summer. Brilliance. Heat. Bitter. Red. Controls heart and small intestines. The Vermilion Bird (Phoenix). Mars.

EARTH. Centre. End of Summer. The Nourishing. Sweet. Yellow. Controls stomach and spleen. Ox or buffalo. Saturn.

METAL. West. Autumn. Destruction and decline. The solid but moulded. Acrid. White. Controls lungs and larger intestine. The White Tiger. Venus.

WATER. North. Winter. The Hidden. Cold. Fluid. Salt. Black. Controls kidneys and bladder. The Black Tortoise. Mercury.

An alternative arrangement is sometimes used in which the order is: Water, Fire, Wood, Gold or Metal, Earth. But Earth in the central position is more traditional.

The Elements also have their yin-yang aspects as associated with plants, metals and planets:

WOOD. Yang. The Pine—Yin. The Bamboo. Jupiter. Tin. Air. Salt.

FIRE. Yang. Burning wood—Yin. Lamp flame. Mars. Iron. Realgar.

EARTH. Yang. A Hill—Yin. A Plane or Valley. Saturn. Earth. The Retort.

METAL. Yang. A Weapon—Yin. A Kettle. Venus. Copper. Sublimate of mercury.

WATER. Yang. A Wave—Yin. A Brook. Mercury, Quicksilver. Aqua fortis. Vitriol.

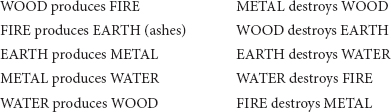

These five agents, powers, or elements, also known as ‘the Universal Quintet,’ are, as Professor Needham says, ‘five powerful forces in ever-flowing cyclical motion, and not passive motionless fundamental substances.’ They are both creative and destructive; they predominate alternatively and each is followed by the one it cannot destroy; they are thus bound up with the cyclical view of Nature as the round of birth, death and rebirth, everything influencing and in relationship with everything else. This process of both giving rise to and destroying each other binds the five elements together and makes them totally interdependent, each having in itself the potentiality of the other and being united in the cosmos.

This is known as ‘the cyclic conquest.’ The five yin and five yang elements make up the Ten Celestial Stems (a cycle of ten characters or ideographs). Tung Chung-shu, a second-century neo-Confucianist, wrote:

The Five Elements move in a circle in proper order, each of them performing its proper functions. Therefore Wood is located in the East and characterizes the ch'i of Spring. Fire is located in the South and characterizes the ch'i of Summer. Metal is located in the West and characterizes the ch'i of Autumn. Water is located in the North and characterizes the ch'i of Winter. Earth dwells in the Centre and is called the Heavenly Nourisher . . . Water is that which soaks and descends; Fire that which blazes and ascends; Wood that which is straight and crooked; Metal that which obeys and changes; Earth that which is used for seed-time and harvest.

There is also this transforming feature in western alchemy. Alphidius says:

The Earth becomes liquid and is transformed into Water; Water becomes liquid and is transformed into Air; Air becomes liquid and is transformed into Fire; Fire becomes liquid and is transformed into glorified Earth, and this effect is what Hermes meant when he said in his secret: “Thou shalt separate the earth from fire and the subtle from the dense.”

The Emerald Tablet says that all things proceed from the One, the One divides into the elements and then recombines in unity.

In the West, too, the elements maintain the yin-yang quality of being contrary but complementary. Their duality exists in the hot and moist and the cold and dry. Fire is hot and dry; Air hot and moist; Water cold and fluid; Earth cold and dry.

The Five Elements are, in every respect, associated with the cyclic view of the universe, which in turn affected Chinese history also, since it was held that the dynasties rose and fell according to the dominance of the Five Powers. The dynasties also followed the Five Elements in taking the Five Colours in turn for use for official dress and occasions. (The last dynasty, the Ch'ing, was yellow.) These five colours also appeared on the pre-communist Chinese flag.

The elements played a vital role in alchemy, medicine and astrology; they were associated with the metals in alchemy; in medicine it stood to reason that they had to be taken into account since they control the bodily organs and each part of the body is affected by the others. Being connected with the planets they related to astrology, which was also closely tied to the cyclic viewpoint. Divinities of stars were also divinities of cycles, each having control of a sixty-year cycle. This ‘cycle of Cathay’ is calculated from the Ten Celestial Stems and the Twelve Terrestrial Branches. Each stem has a yin and yang aspect, counting as one: hence 5 × 12. Also the lowest common denominator of 10 and 12 is 60 (the year 1984 starts the next cycle, which continues until 2043). Years are yin or yang according to whether they are even or odd numbers, but cycles always start with a yang number and end with a yin. The Ten Celestial Stems with the Twelve Terrestrial Branches together form a cycle of days, months and years.

The cyclic standpoint is fundamental to all alchemy and is symbolized by the Ouroboros as the dragon in the East, the serpent in the West, swallowing its own tail; it represents the whole alchemical work. It is the cycle of disintegration and reintegration, the power that perpetually consumes and renews itself; it is also the latent power of the prima materia, the undifferentiated in which the end is implicit in the beginning, or ‘the never-ending beginning,’ or, again ‘my end is my beginning.’ The symbol appeared early in both eastern and western alchemy and in Chinese, Egyptian and Greek iconography. In the latter the serpent was depicted as encircling the words ‘All is One.’ In Chinese alchemy it is expressed thus: ‘The ends and origins of things have no limit from which they began. The origin of one thing may be considered the end of another; the end of one may be considered the origin of the next.’ The neo-Confucianist Chou Tun-i wrote that there always have been ‘successive periods of growth and decay, of decay and growth, following each other in an endless round. There never was a decay which was not followed by a growth.’ A Taoist doctrine maintains: ‘There is no real creation or destruction, only densification and rarefication.’

Great importance has always been attached to the number five, known as the Magic Quintet, in all things Chinese and especially in alchemy and magic. In alchemy the significance of the number rests on its astrological associations with the five major planets (later discoveries of other planets were not allowed to alter the cosmological importance of the original five) and the five metals, lead, mercury, copper, silver and gold. These were combined in varying proportions and procedures with their five planets. The processes in alchemy were also controlled by the number five; metals should be heated, or roasted, five times, or in multiples of five, up to five hundred.

In ordinary life there were also endless groups of five: the five planets, sacred mountains, social relationships, blessings, virtues, sacrifices, colours, internal organs, tastes, poisons, tones, grains, pungent flavours, directions (North, South, West, East and Centre), spiritual and domestic animals, while five memorial poles were put on graves to represent the Five Elements at rites of the commemoration of the dead. In magical invocation, or as a talisman, the Five Elements are represented as:

Five also holds sway in alchemical yoga where the five vitalities are used in arousing the kundalini-like circular power in the body; the vitality of the heart, spleen, lungs, liver and kidneys.

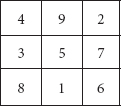

Exoteric alchemy was closely associated with magic and use was made of talismans and amulets when heating the mixture for the five or multiple of five times. The chief of these amulets was the magic square, using the digits 1-9 with 5 in the central place. This square was the basis, one might call it the mandala, of the Imperial Temple of Enlightenment, used mainly for the regulation of the calendar, the Chinese years being variable in length, and for other astrological purposes.

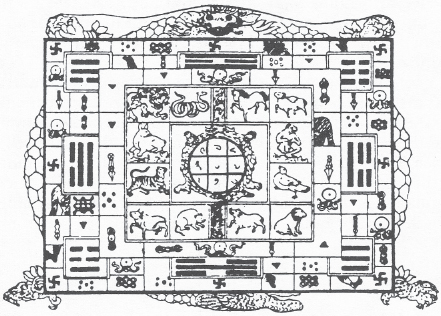

The cyclic death and rebirth symbolism is also inherent in the Pa Kua, the Eight Trigrams denoting the eight directions, associated also with the numbers 1-9, omitting 5 since it is the centre. The Eight Trigrams were said to have been revealed to Fu-hsi, on the back of a tortoise (the tortoise-shell is universally employed in divination), and a Tibetan tablet shows the trigrams with the animals of the Zodiac, or the Twelve Terrestrial Branches, on the back of a tortoise, while another tortoise-shell appears in the centre, supporting the circle and magic square. The kua were associated with alchemy since its processes depended on divination of auspicious times and seasons. The I Ching was the basis of this divination as ‘there is absolutely nothing which does not depend on the symbols of the Book of Changes.’ The I Ching carries this cyclic significance throughout. The trigrams represent forces in Nature and the transmutations involved: ‘Each in turn gives birth to the next and is overcome by the next in turn.’ This is the interplay of the yin-yang powers and the Five Elements which are the agents or movers; this principle, carried in the trigrams and hexagrams, is implicit in all Nature.

Taoist cosmology assumes a harmonious pattern in the universe; its changes are not brought about by chance or by the arbitrary will or decrees of a creator-god, but by the spontaneous workings of the Tao: everything in it is interdependent in a cyclic recurrence, which, as Professor Needham points out, ‘does not necessarily imply either the repetitive or the serially discontinuous.’ He writes of the Tao as ‘a field of force’: ‘All things oriented themselves according to it, without having been instructed to do so, and without the application of mechanical compulsion . . . the same idea springs to mind in connection with the hexagrams of the I Ching; yang and yin, acting as the positive and negative poles respectively of a cosmic field of force.’

Tibetan Mystic Tablet on the back of a tortoise

In the Shu Ching, in the chapter on the Great Plan, it is said that the elements were produced by the powers of yin and yang and their twofold breath, ch'i, which must be kept in balance to produce favourable conditions in all things.