There is no land without its magic lore and beliefs in which there occur unexplained phenomena and relationships with invisible powers. These are called occult or arcane because their workings are not understood in the ordinary world of the senses and reason. In China, popular religious Taoism, as opposed to the classical philosophical branch, has always been associated with magic, stemming back definitely to the Han dynasty, and in tradition to such wonder-workers as the Yellow Emperor, some 3,000 years BC, and the hsien Ch'ih Fu who became completely rejuvenated after taking the elixir. The proximity of Shamanistic tribes also introduced magical and spiritualistic cults, while magical lore was again widened by contact with Indian thought, brought into China by exchange of culture when Chinese emissaries were sent to study Indian scholarship and when Buddhist missionaries arrived in China

Magic is closely associated with alchemy in experiments and experimental science, with the ‘powers’ of religious beliefs and with the medicinal knowledge of making potions, poisons and drugs. It concerned all aspects of life, in this world and the next, and was not limited to either. It is probably true of Chinese magic that it was, as E. A. Wallis Budge said of Egypt, ‘older than belief in God.’ Professor Needham states that science arises out of magic: ‘In their earliest steps they are indistinguishable. Taoist philosophers, with their emphasis on Nature, were bound in due course to pass from the purely observational to the experimental . . . That the mastery of Nature by manual operations is possible was the firm belief of magicians and early scientists alike.’ In fact in ‘the early sixteenth century in Europe science was commonly called Natural Magic . . . even Newton has with justice been called “the last of the magicians” . . . one cannot emphasize too much that in their initial stages there is nothing to distinguish magic from science.’

Olympiodoros, an official at the early Byzantine court, in the fifth century, was a famous alchemist but was also noted for his knowledge of medicine and as a magician. He maintained that the success of alchemical experiments did not depend on the exact following of recipes but required the assistance of magic and magical powers. Various rulers and Popes in Europe were known as sorcerers: Popes Honorious III, Leo III, John XXII and Silvester II were known to be magicians, while Catherine de Medici and her son Henry III encouraged magicians and sorcerers who dealt with ‘unknown drugs.’ In the West, as much as the East, magicians were part of the court scene, of government and of the priesthood. Among monks were Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus, and at the lower level among the ordinary people the village sorcerer, witch or wizard fulfilled the same functions. In China these were paralleled by the noted alchemists and magicians at the courts of the Emperors, by the Taoist priests of the local temples where the populace worshipped, and by the lower orders of hsien who worked the same wonders as the western sorcerer and dealt with the same practices and powers such as fortune telling, making amulets and talismans, commanding spirits and raising ghosts. Nor have these customs died out in either East or West.

Although there is obviously a close link between Shamanist and Taoist alchemical-magic practices, they functioned on different levels in that the shaman was trained only on the magico-religious plane while the Taoist-alchemist was a scholar and searcher after ‘ancient wisdom’ on an intellectual level, though in Taoism there was the division between the esoteric and exoteric branches, the latter being as full of magic and spiritism as was Shamanism. Shamanism, however, represents the oldest response of humanity to the world around. It is ‘primitive’ in both senses, in that it is the magico-religious belief of a simple and unsophisticated civilization and in being an originally pure doctrine of the macro-microcosmic relationship which has since degenerated. Shamanism still shows traces of a once highly-developed cosmology. Like the alchemist, the Shaman contacts not only demons but also cures diseases; he is a diviner, exorcist, invoker of spirits, a medium, healer, fortune-teller and rain-maker; or, in reverse, he can arrest storms; he also uses ‘words of power.’ The reason for concentration on and contending with demons, rather than being concerned with good spirits, is that the latter are helpful in any case and there is nothing to be feared from them; the former are continually intent on doing harm and must be guarded against incessantly. There is no doubt that the Shaman has ‘powers;’ even if his spirit powers are called in question, it is certain that he can carry out an ecstatic dance, in a crowded yurt, with some thirty to fifty pounds of iron discs and other objects attached to his robes, flinging himself about with closed eyes yet never touching any of the audience and able to lay his hands on any object he requires while still in trance.

There have always been two kinds of magic: the ‘black,’ which involves the invocation and co-operation of the demonic world and attempts to coerce and control these dark powers and force them to work in harness, and the ‘white,’ which deals with beneficial spirits and aims at working good and healing. There is also a misty borderland between black and white in the use of talismans, charms and words of power, practices which have endured for thousands of years and are still fully alive in the modern scientific-rationalist climate. People or teams still carry their mascots, have lucky numbers, wear amulets and ‘touch wood’ after any boast.

It has always been assumed that the future can be foretold and accepted that certain people have divinatory power. Oracles and seers were consulted and signs and portents read in such things as the flights of birds, the entrails of sacrificed animals, the throwing of sticks or coins, the markings on tortoise-shells; mirrors, crystal balls, bowls of water, and bones were also used in divination. Many of these practices, though, had an esoteric aspect beyond the outward-seeming superstition. Exoterically, talismans, charms and other means of avoiding or curing misfortune or calamities, both natural and spiritual, were believed actually to encapsulate the spirit concerned; esoterically, they were the means of conveying the idea of psychic balance of the forces of the cosmos and the sense of the mystical unity of all things.

In the East there was no reason why all such powers should not be beneficent provided the necessary precautions were taken, the good spirits were consulted and evil ones kept at bay; but in the West the connection between spirits and humanity was dubious, since magic had been learned from fallen angels who married the daughters of men; as the angels were ‘fallen,’ the arts they taught were tainted with evil.

Magic was practised not only to bring about alchemical transformations but also to summon the Immortals. The court magicians employed by the Emperor Wu were used not so much to produce gold as to call up the Immortals and spirits—particularly, in this case, the spirit of the greatly-mourned favourite, the Lady Wang. The Chinese Festival of the Moon Palace rose from Taoist magic and commemorated the court magician's feat in enabling the Emperor to visit this beautiful maiden who lives in the Moon Palace.

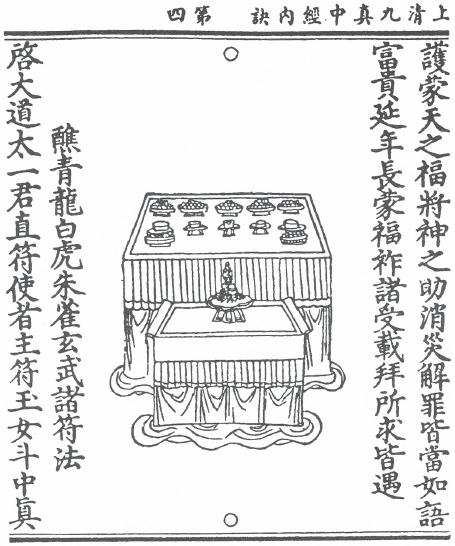

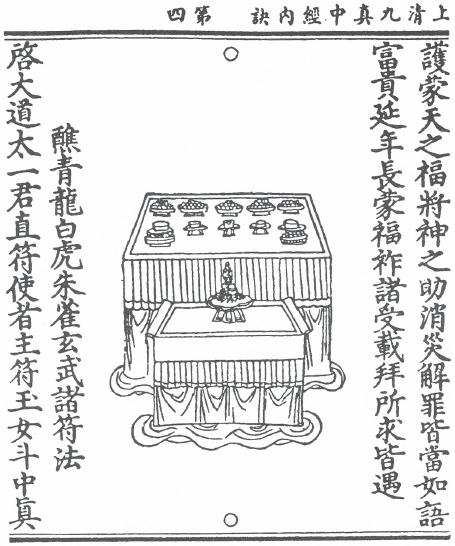

Alchemical altar with offerings

In the realm of the occult, good and evil spirits can be used against each other, but as there is considerable danger in such an encounter the magician, shaman or alchemist must be under the protection of forces of a superior spiritual order. Hence, the alchemist puts himself under the tutelage of some deity—for example, the God of the Stove or, on a higher level the Great Spirit or the White Light. In Hinduism, the Vedas allow magic to be lawful only for the pure in heart, while, like the alchemist, sadhus and fakirs concerned with the occult must undergo severe discipline.

There are also spiritual visitants who take an interest in operations on the earth plane. As Ko Hung says: ‘Spirits and gods frequently cause miraculous and strange things to occur among men. In our classics there is much evidence regarding them.’ Among these interested persons must be ranked the dead who, for some reason or other, wish to make their presence felt in the mortal world. A powerful magician or hsien could also summon the dead to serve his purpose, as in the case of the noted hsien Liu Ken. He was once a court official at the capital of Ch'ang-an, in the Later Han dynasty. He abandoned court life and retired to a cave on the edge of a precipice. He also abandoned clothing and grew a covering of hair a foot long, but when visited, or in company, he could suddenly assume the conventional brocade robes of the scholar-official. He used his magical powers to help the local populace, providing food and healing illness, but a new governor of the province regarded him as a wizard and intended to have him tried and executed. Commanding Liu Ken to appear before him, the Governor challenged him to call up some spirits to his aid in his present predicament. Liu Ken wrote at the Judge's table and there followed an eerie whistling and clanking. The wall of the courthouse fell in and through the gap came a troop of soldiers escorting an enclosed carriage. The wall then closed behind them. Liu Ken then ordered the occupants to be brought out and an old man and woman appeared with hands bound and a noose round the neck. To his horror the Governor recognized his dead parents, who upbraided him for having been of no use to them in his life, since his official preferment had not taken place until after they had died; now, in death, he was causing them harassment and humiliation in persecuting a blameless hsien. The Governor immediately prostrated himself before Liu Ken and pleaded that his father and mother might be released. The hsien then ordered the chariot away; the wall opened and closed again behind it and Liu Ken vanished. But this was not the end of it for the Governor; his wife died soon after but came back from the next world to tell him that his parents were so enraged at his unfilial behaviour that they were going to kill him. A month later he and his son and daughter all died.

As a background to this story it must be realized that in China the whole family was held responsible for the misdeeds of any member and was involved in any punishment. Similarly, the entire family was aggrandized when a success was achieved or honour conferred, even when the honour was posthumously awarded; this had the advantage that, if anyone had been accused falsely or executed when innocent, he—and his family—could be exonerated and recompensed after death. The next world was regulated on the same hierarchic-bureaucratic lines as that of imperial times, when there were distinct grades of officials and classes of persons. This firm and practically applied belief in the spirit world permeated Chinese social and religious practices: the realm of spirits was taken seriously, nor have these beliefs died out, as witness a recent account of a spirit-marriage in Peking. A girl, having been killed in an accident before she was married, was saved the ignominy of arriving unwed in the after-life. A recently-dead youth was found; the normal match-making ceremonies were undertaken by a go-between who settled the dowry with the girl's father; there was the normal wedding ceremonial and feast and then both bodies were buried in the husband's tomb. The usual offerings of money, clothing, food and wine were offered at the graveside. Traditionally, all the requisites for a comfortable life in the next world—servants, clothing, money—were taken in the funeral procession in paper effigies or forms and burned at the grave to ascend in smoke to the heavens.

Spirits, if the body had been properly interred and there was a home to live in, were contented and well looked after in the ancient ancestor reverence; but if the right conditions were not followed, or if there were no home to go back to, the spirit then became a wandering ghost, unhappy in itself and a threat to the living; hence the many rites for preventing such ghosts from causing harm and for banishing them. This, too, explains the great importance of having sons. Daughters marry into other families, but sons perpetuate the family home and provide the necessary home for the ancestors. There are various methods of keeping ghosts at bay. ‘If you meet a ghost coming and shouting continually to you for food, show it a white reed and it will die instantly. In the mountains ghosts are continually creating confusion to make people lose their way.’ They also cause illness and disease, but if the right magic is employed they can be controlled and made to serve the living. For this purpose spells, incantations and ‘words of power’ were used, both oral and written. There is a universal belief in the power of sound in words. In Egypt the cult of immortality was as much of an all-absorbing interest as in China, not only in the preservation of the physical body but also in magical formulas which helped the dead in the next world. Both Isis and Thoth/Hermes held the secret of sound and Isis revivified the dead Osiris, killed by his brother Set, with magic words; the exact pronunciation and understanding of their meaning was of the utmost importance. In Hinduism the sound OM penetrates and sustains the whole cosmos.

Servants for the Dead Effigies following the funeral.

Summoning spirits or demons is universally done by the magic Power of the Name. Spirits serve the magicians, shamans and priests, and are often treated with contempt by the masters who exercise power over them. Incantations could force demons to leave their abodes and appear before the sorcerer at his will. Divine names were used in incantations and invocations; these were esoteric and a jealous guard was kept on them. There was a constant struggle between the shaman-magician-alchemist and the spirits he needed to serve him; either he obtained the mastery over them or they mastered him and he would become ‘possessed.’ In Chinese alchemy possession belonged only to the failures who, in consequence, require the rites of exorcism. Wandering ghosts and spirits could also take possession of the body of those making mistakes or trespassing on forbidden ground while insufficiently ‘protected.’ Possession was taken seriously and in religious Taoism priests were trained in exorcism, while magicians used their powers to expel possessing spirits.

Possession can be voluntary or involuntary. Priests and mediums could be possessed by spirits when in trance. In the lower orders these entities could be demons; in the higher states, gods, goddesses or hsien could speak through the medium. It was in cases where demons or ghosts took over against the intentions of the person that the individual became possessed to his or her detriment and so required exorcism. Priests, shamans and mediums, once possessed, had command over all magical powers: they could slash themselves with knives and remain unhurt, swallow fire, walk on live coals, cause objects to fly through the air or levitate themselves; such powers have been examined and attested to in modern times. I witnessed them myself at close quarters when itinerant magicians displayed their abilities in the market place with people crowding round within touching distance. Swords, offered to the crowd to test, were ‘swallowed’ and coals taken from a brazier were also offered for inspection then put into the mouth and held there and spat out, still blazing hot.

These magic powers were used by the ‘bellows blowers’ alchemists in their work, but the true hsien did not use the mastery of spirits in his work on the spirit; that was done by yoga, self-mastery and by co-operation with Nature to become one with her rhythms.

The Sorceress (wu) played a vital part in ancient Chinese magic. She purified herself with perfumed water, donned ritual robes, took a flower in her hand and mimed her journey in search of the gods or goddesses. She danced ecstatically to the music of drums, flutes and song until she fell exhausted and the deity invoked then spoke through her. Like the hsien, the wu could become invisible, levitate, travel great distances in the spirit and could produce all the magical and mediumistic phenomena. Her male counterpart was called a hsi.

A sword swallower

Chinese alchemists were experts in making perfumes, which occupied an important place in all religious rites and any ritual-social occasion. Indeed, scents have always been valued and used in all aspects of Chinese life: witness the numerous scents employed in perfuming Chinese teas. Among ritual perfumes incense sticks were prominent. In Taoist temples incense burning is a central rite and traces of its ancient alchemical connections can be seen in the name of those who attend the burners or the altar—‘furnace masters.’ Incense also has magic qualities in that it dispels evil spirits and other undesirable entities such as wandering ghosts and prevents them from interfering in either religious or social rites or in alchemical experiments. Incense sticks are an essential part of divination, especially when consulting the I Ching. Other uses were as timing devices for alchemical experiments and for fumigation. Incense has always been employed in purification and as a homage to divinities; it suggests the ‘subtle body’ rising as a spiritual substance and a ‘perfume that deifies.’ It is also ch'i and symbolically the principle of change. The smoke rising upwards forms an axis mundi between the two worlds and carries messages and prayer heavenwards; it is a combination of fire and air, symbolizing the power of both, but especially the former in alchemy.

Books can also work magic. The Chinese have always had a great reverence for books and printed matter. (As a child one's amahs would never allow a book to lie on the floor or be dropped. They could not read the books or know their trivial nature, but they were printed and therefore to be revered.) Classics must be wrapped in silk and stored in a ‘purified place’ and ‘whenever anything is done about them one must first announce it to them, as though you were serving a sovereign father.’ If certain classics are kept in a house they will ‘banish evil and hateful ghosts, soften the effects of epidemics, block calamities and rout misfortunes.’ It also helps to give a sick person, or a woman in labour, a certain classic to hold. In building a new house or preparing a tomb, copies of the ‘Earth August Text’ should be taken to the site; the household will then become rich and prosperous, the grave protected from robbers and ghosts. Some scrolls enable people to change sex, age or character, to produce miraculous food, change into birds or animals, or raise wind, rain or snow.

Talismans and amulets are universally employed to ward off evil spirits. Peach stones, as the kernel of the fruit of immortality, are particularly efficacious and are frequently carved into apotropaic forms, such as a figure of a hsien or of a Buddha, while peach wood is used for the pen in automatic writing. Swords made of cash linked together by red thread work magic in cutting off demons and the cash sword is used in rites of exorcism. The red thread is in itself effective and red and yellow are used to bring luck and ward off evil on all occasions. Yellow and red paper is employed for charms, as being also the colours of gold and cinnabar. Bells, too, are used in magic and effectively scare off evil spirits; for this purpose they were often hung from the points of temples or pagodas.

The seal of Lao Tzu, an all-powerful talisman and bringer of good fortune, worn by mediums.

Mirror magic is widespread. Mirrors can be used for summoning gods and genii, but in this case it is important to know the names and the types of clothes worn by each, otherwise one might fail to recognize him or her on arrival and so cause considerable umbrage, with potentially disastrous results. Mirrors enable the shaman and magician to see things far off and to find things which are lost; they also reveal the true nature of the person; for example, if, when one is approached by a supernatural person, one looks into a mirror, a fox or a tiger may be reflected masquerading as a human. The ‘burning mirror’ could create fire and was yang; the ‘dew mirror’ collected dew at night called ‘moon water’ and was yin. Mirror magic was also used in the West to hold over herbs collected for alchemical purposes; the plants had to be picked before sunrise, under a waning moon, and the process required the person to be ‘barefoot, chaste, ungirded and wear no ring.’ One can also divine from sun or moon rays reflected in a mirror or water.

As can be seen from this, herbs are subject to both astrological and magical influences and gathering them demanded an exact knowledge of times and seasons; this, again, obtained in eastern and western alchemy. In the West instructions were given for finding one's guiding star, which involved the herb being gathered at the right time, in a state of purity, kept in linen, with a whole grain of wheat from a loaf of bread, then placed under the pillow. After prayers are said to the seven planets, repeated seven times, one's guiding star will be revealed in sleep. Magic also enters when one is instructed to make a circle round the herb, using gold, silver or ivory, the tooth of a wild boar or the horn of a bull.

A cash sword

Messages and instructions could be received from the spirit world and from hsien through automatic writing, which was known to have been used in early Sung times. It was said that the Immortal Tung Pin, after invocation, communicated through a willow stick held by a blindfolded person over a tray of sand. This method of communication is of considerable interest since it is still in use today. The willow or peach stick, or pencil, can be held by one blindfolded, or it is supported on the upturned palms of the medium's hand, a position in which no muscular control can be exerted. The pencil appears to assume a life of its own, characters are formed in the sand and interpreted either as messages or alchemical instructions. Even books could be so transmitted: the Secret of the Golden Flower was reputed to have been written in this way.

As in all things Chinese, absolute courtesy must be observed. A spirit summoned to give aid is offered a chair to sit on and asked to give his honourable name and to identify himself by enumerating his august titles and the period of history he honoured with his presence. The spirit is bowed to and ritually thanked for help given; in return he depreciates his efforts and thanks the company for their invitation.

There were endless schools of magicians, soothsayers, horoscopists, geomancers and those who watched the heavens for portents. There was a huge trade in talismans and charms and, on the less magical side, there also existed a science of physiognomy which studied physical features and characteristics, but also drew from them conclusions as to the fate of the individual.

Associated with both ch'i and magic was the practice of geomancy, known as feng-shui, literally wind-and-water. It was the science of favourable conditions, climatic, physical and of the spirit world and was used in locating the right situations for temples, houses, graves, or the best places for business transactions. The abodes of both the living and the dead had to be in harmony with the cosmic currents and the breath of Nature, the ch'i of the earth. It required the offices of diviners, known as ‘professors of divination,’ the geomancers, to determine favourable situations which must also be governed by the yin-yang features of the scene. For this the geomantic compass was used. At the centre of the instrument there is a mariners' compass, an early Chinese invention, the ‘Southpointing needle,’ also called the Tai Chi. The sixteen successive circles round the compass depict, first, the pa kua, then the twenty-four celestial constellations and after that the various numerical and occult calculations based on the sexagenary cycle, the constellations and the Twelve Terrestrial Branches. Naturally, favourable sites, times and seasons also affected the times and places for alchemical experiments.

Talisman of one hundred forms of the character shou: Longevity.

The ability to work magic is not, according to Ko Hung, a special endowment but is acquired through learning from Masters and taking elixirs. These individuals were not born with the knowledge of these things: ‘It is thought that the divine process cannot be acquired through study so I would remind you of bodily metamorphoses, sword swallowing, fire eating, disappearing at will, raising clouds and vapours, snake charming, walking on knife blades without being cut.’ In another passage he wrote: ‘Narrow-minded and ignorant people take the profound as if it were uncouth and relegate the marvellous to the realm of fiction . . . what narrow-mindedness and ignorance.’ But for all its powers he decided that magic will not be able to confer Fullness of Life on its practitioners. ‘They may cure illness, raise people from the dead, go years without hunger, command ghosts and gods, disappear at will, see what is occurring a thousand miles away . . . and know misfortune and good fortune for things that have not yet occurred, but none of those things benefits their longevity or immortality.’ And again: ‘Only those who have Tao can truly perform these actions, and, better still, not perform them, though able to perform them.’