CHAPTER 5

When I got back to Dublin I told my dad about meeting Norman Garrad and how I had refused his offer of working for him. My father never usually got annoyed, but this time he was furious and asked me, did I realise what an honour it was to have been asked to drive for Rootes? He told me that the Rootes Group was a famous British car manufacturer and a major motor dealer business, with offices in the West End of London and plants in the Midlands and the south of England. I realised from his reaction that maybe I should have paid Mr Garrad’s proposal a little more attention.

A few months later I received a letter from the Rootes Group, telling me that they were delighted that I was taking up Norman Garrad’s offer to join the team. My mother explained that she had written to Rootes’ headquarters in London, telling them that I had changed my mind and would be available to join them. My parents insisted this was a chance of a lifetime and I soon realised they were probably right.

Apparently, Norman Garrad had been behind me on the road when I was driving for Sally Anne, and a friend since told me that he is quoted in The Rally-Go-Round by Richard Garrett as saying: ‘She was pressing on very smartly and appeared to be the only one alive in the car. I stayed behind her for about two hours, by which time I realised that she had more than average ability.’ Norman was a shrewd and experienced businessman and saw the advantage of having this long-legged Irish girl sitting on the bonnet of one of his cars, or, even better, doing the driving. I was often referred to as the ‘blonde bombshell’. In his eyes, I was a dolly bird and potentially a great marketing tool too.

The aim of car manufacturers is to sell cars, and rallying and racing was one of the ways to get their message across: a pretty woman adorning their cars was always a help. One of Norman’s publicity stunts was to put my name down for Le Mans one year. The 24 Heures du Mans is one of the most prestigious automobile races in the world and on the entry list I was ‘R. Smith’ driving a Sunbeam Alpine. Norman knew full well that women weren’t allowed to drive in the race because in 1956 Annie Bousquet, an Austrian-born French driver, was killed in an accident when she lost control of her Porsche 550 in the early stages of the 12 Heures de Reims. The negative publicity and public outcry caused the French motorsport authorities to prohibit women from entering major races, and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, organisers of the Le Mans 24 Heures, banned female drivers from competing in their race. Yet previously, in June 1955, a disaster at Le Mans occurred when Pierre Levegh crashed and large fragments of debris flew into the crowd, killing 83 spectators and injuring many more. Despite this appalling accident, the 24 Heures du Mans went on uninterrupted, year after year, but without women drivers.

Norman had arranged everything. I was duly sent for the medical, and when I entered the room the doctor called out ‘Smith’ and I stepped forward. Not looking at me, he said, ‘Drop your trousers.’ I gasped and he turned around and looked at me in astonishment. ‘You are not a man,’ he said. Well spotted, I thought. ‘You cannot race. No woman is allowed to race in Le Mans.’ The French doctor was a lovely young man, which made my rejection easier to take. The press were all over it and Rootes got loads of publicity, even though none of their cars won that year. In 1971 the French authorities lifted the ban and women were allowed once again to race, but it was too late for me.

Norman Garrad was a very clever man with a weakness for Michelin-starred restaurants. On a recce for the Monte Carlo Rally, when we were preparing pace notes, he would say lunch at 1.30 at such and such a place. It would be out of our way and the crew would protest – it was all right for him, he could just sit there and drink his nice wine but we had work to do. It gets dark very early in January on the continent, and by the time we had this gorgeous lunch the day was over. I remember rally legend Paddy Hopkirk got annoyed and said, ‘We are here to practise. Let’s have a meal in the evening,’ but Norman paid no heed to him. I was only the newcomer and said nothing – in any case I didn’t talk back to my elders and betters in those days. Of course, now I would be only too happy to linger over long lunches in Michelin-starred restaurants in France with any well-dressed gentleman who was offering.

I made the front page for being a woman (Daily Mail)

Norman was a force to be reckoned with and most of the time I went along with whatever he suggested until an incident in Greece in 1965. We were in Athens a few days before the start of the Acropolis Rally, staying in a hotel right on the beach. The boys in the Rootes team were all going out to dinner and asked me along. Delighted, I was in my room getting dressed when there was a knock on my door and there was Norman. He must have heard that I was going out to dinner with the rest of the crew because when I opened the door he said: ‘You needn’t think you are going out with the boys. I want you to have dinner with me in my room tonight.’ Norman was my boss and I suppose I could have said, ‘Yes, of course, I’ll stay in and dine with you,’ but I didn’t. I told the boys what he had said and they told me to come out – I knew I needed the crew on my side if I was to get through the rally.

Furious, Norman said, ‘If you don’t come to dinner with me, you’re sacked and I’m sending you back to London tomorrow.’ I went out with the crew anyway and when I came back to my room there was an envelope under my door containing a ticket from Athens to London for the next day. When I told the other drivers, they said to ignore him – ‘How would he explain to Lord Rootes why he had sacked you before the rally even began?’ they said. So I stayed put and Norman relented and said he would let me stay and do the rally this time. He didn’t ask me to dinner again.

When I was with Rootes, I did the Monte about six times, the Scottish and the Geneva Rallies, the Circuit of Ireland and the Tour de France, which wasn’t a bicycle race then, most of the time in the Hillman Imp. I loved that little car. Some of the boys were trying to drive the Imp as if it was one of the bigger cars but it was fragile and needed a gentle hand.

The Imp was the first mass-produced British car to have an engine in the back and was a direct competitor to the British Motor Corporation’s Mini. They had put it into production in a hurry and it hadn’t really been tested properly. Initially, they were falling to pieces when we drove long distances at high speed, and the Imp was never really as fast as the Mini.

I was learning all the time and my good friend Cecil Vard, one of the first Irish drivers to take part in the Monte Carlo Rally, finishing third in 1951, gave me some great advice. He taught me to have the courage to go slowly. Before that I would go flying into a bend, but I eventually saw sense and followed his advice.

Cecil was a talented man, a furrier by trade; he, along with his brothers, Leslie and Jack, owned ‘Doreen’, manufacturers of ladies’ garments in Dublin. All his life he was associated with charitable work and in 1955 he was a founder member and the first president of the Dublin Lions Club. I will always remember his kindness and generosity to me over the years.

I started the 1963 Monte from Paris in a Sunbeam Rapier with my co-driver Rosemary Seers, who Rootes had chosen to drive with me. She worked in London and I didn’t know her at all and we had nothing in common. When we were checking in at the start, I noticed that Rosemary was using her left hand to write and her signature was a scrawl. It was then she told me that she had had a slight stroke and she could navigate but wouldn’t be able to do much of the driving. When I heard that, I was determined to keep her hands off the steering wheel.

The weather conditions were terrible, and as we left Paris the roads were frozen and it was snowing hard. There were snowdrifts all over Europe that year and the 13 Athens starters didn’t make it at all and only 10 of the 59 coming from Glasgow reached Monaco. The snow and ice were bad enough, but fog covered the Alps and I was driving relatively slowly when another rally car came up behind. It was Timo Mäkinen in his Austin Healey and I let him pass. I tucked in behind him, put my foot down and tried to follow, keeping his tail lights in sight as best I could. For a while I lost him and then spotted his tail lights again, but unfortunately he had gone around a hairpin bend. I thought he was straight ahead of me, followed him and we plunged over the edge.

The car rolled over several times on its way down and ended up lodged in a tree. Rosemary Seers was thrown clear of the car; because of her bad arm, she hadn’t fixed her seat belt properly. I unstrapped myself and scrambled up the mountainside to the road. The first few cars went straight by and I don’t blame them, they were out to win the rally. Eventually, two English-speaking German drivers in a Mercedes stopped. I didn’t feel the cold, shock does that, but they quickly placed a rug around me and put me in their car. They scrambled down the slope with a big flashlight, found Rosemary and carried her up to the car. It was only then, as I sat in the back of the car with the unconscious Rosemary beside me, that I got the shakes.

There were no houses nearby and it was a while before they found a farmhouse. An ambulance came and demanded money to take Rosemary to the nearest hospital, which was in Carcassonne, and John Rowe, the PR man from Rootes, drove up and took me on to Monte Carlo. Rosemary had cracked her skull, but luckily I had nothing to show for my trip over the edge of the precipice. It is invariably the co-drivers who get hurt when such accidents happen.

I stayed in the hotel in Monaco and went to the ball on Saturday night, as planned. The next day, John Rowe and I went to Carcassonne to find Rosemary and take her to the American Hospital in Paris. The hospital in Carcassonne hadn’t looked after her very well because she had arrived with no money or insurance. Rosemary told us that all she had been given to eat was brown bread and some fish soup. She kept drifting in and out of consciousness but somehow we managed to put her in the car and then on to the train.

It was an overnight trip to Paris, but we had no couchette booked. We laid Rosemary down on one of the long seats in the carriage, but each time the train lurched she fell off and we had to catch her. After this happened several times, we decided to make a bed for her on the floor with our coats and a blanket, where she would be safe, and took ourselves off to the restaurant car.

There was an ambulance waiting for us at the station in Paris to take Rosemary to the hospital, and we went to catch the ferry back to England. She made a full recovery but we never drove together again after that. She should never have come on the rally that year as she was so unwell, but hindsight is a wonderful thing, as they say.

My career with Rootes had begun in earnest and I went on to drive the Hillman Imp in the Monte Carlo Rally many times. In 1964, with Margaret Mackenzie as my co-driver, the run was comparatively trouble-free except for the fog and me being nervous, remembering what had happened in the previous year. Paddy Hopkirk, a brilliant rally driver from Northern Ireland, was the outright winner in 1964 and all the team were so proud of his achievement. Paddy has won the Circuit of Ireland five times, as well as numerous rallies in Europe. He was honoured with an MBE in 2016.

Anyway, as we drove through the gateway of the Prince’s Palace of Monaco, there was Princess Grace in a suit of pale green tweed. She looked even more beautiful than in the newspaper pictures or in her films. Along with the other drivers, I was introduced to her and the Irish flag was fluttering in the breeze, although it was ‘God Save the Queen’ playing in the background. I got the feeling that Princess Grace was delighted to be handing the prize to an Irishman as she greeted Paddy Hopkirk so warmly and with such a lovely smile. I had to make do with a plaque for coming fifth in the Coupe des Dames that year. The Coupe des Dames was awarded to the Best Female Finisher in the Monte Carlo Rally for the first time in 1927. It is a lady’s prize but a certain number of all-female crews had to compete before it could be awarded.

The rich and the famous attend the grand ball held every year in the banqueting hall, wearing fabulous clothes and dancing as the orchestra plays; I feel so lucky to have been part of that.

The next year I drove with Margaret Mackenzie again, and with Valerie Domleo in 1966. Val was terrific – very solid and steady – and she had driven with Pat Moss, sister of Stirling, on a number of occasions. I asked her to be my co-driver and she was very happy to join me and we struck up a good friendship. She was with me when I won the Tulip Rally in 1965 and my co-driver that year in the RAC Rally, the Coupe des Alpes and the Acropolis.

In 1966, 10 cars were disqualified from the Monte Carlo Rally because of so-called faulty headlights. When we were doing practice runs that year in France, we were constantly being told that we had no chance. ‘France is going to win this year,’ everyone said. ‘It’s the centenary year.’ The French seemed to think it was a foregone conclusion too. When the first three to cross the finishing line were Timo Mäkinen and Rauno Aaltonen from Finland, and Paddy Hopkirk from Ireland, all driving BMC Minis, the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile in Paris said the iodine quartz headlights fitted on the British cars were not standard. Paddy Hopkirk said it was a bit like saying that because you put a red roof on your car instead of a green one, you were disqualified. Pauli Toivonen, a Finn in a French Citroën, was declared the winner. Toivonen wasn’t happy because he rightly felt that it was a wrong decision.

(Rootes Motors Ltd)

I had won the Coupe des Dames and was disgusted when I was disqualified because the women who were pronounced the winners hadn’t even finished. They were all French, of course, and driving French cars. Prince Rainier, who had always been there in previous years, was so angry about it that he left the rally without attending the prize-giving. I said at the time that I would never do another Monte Carlo Rally, but of course I did.

I drove with Valerie Domleo again in the 1967 Monte. Unfortunately, that drive was not a good one for us. We were lying way up front and as we came down the icy mountain road it was snowy and I was going fast. Suddenly, the car skidded and I hit the hub of the back right-hand wheel against the rocks and it shattered, leaving me with only three wheels on my wagon. That was a big disappointment but it was my own fault, I was just going too fast. We had to keep going as it was a very narrow gorge and we limped along until we were able to stop at the widest part so that other cars could pass.

In the 1968 Monte, I drove the Sunbeam Imp with Margaret Mackenzie. A very bright girl, with an upper-class English accent, like many of the girls in the business at that time, she was very competent and usually a great navigator. I had driven with her before in the 1964 Geneva Rally in a Sunbeam Tiger, a sports car with a big engine that I loved. I only got to drive it once – the big cars were almost always kept for the boys. We were going well until Margaret made an error on the outskirts of Geneva, directing us into heavy city traffic. Still, we made it to the finish; only 38 of the 74 starters managed that.

I did well in most of the rallies I took part in, winning the Coupe des Dames many times, but to beat the men outright was something I dreamt about. Sometimes dreams come true and competing in the Tulip Rally in 1965 was one of those times. The whole Rootes team were taking part in the Tulip, one of the big events of our rally year, and again I was to drive the Hillman Imp.

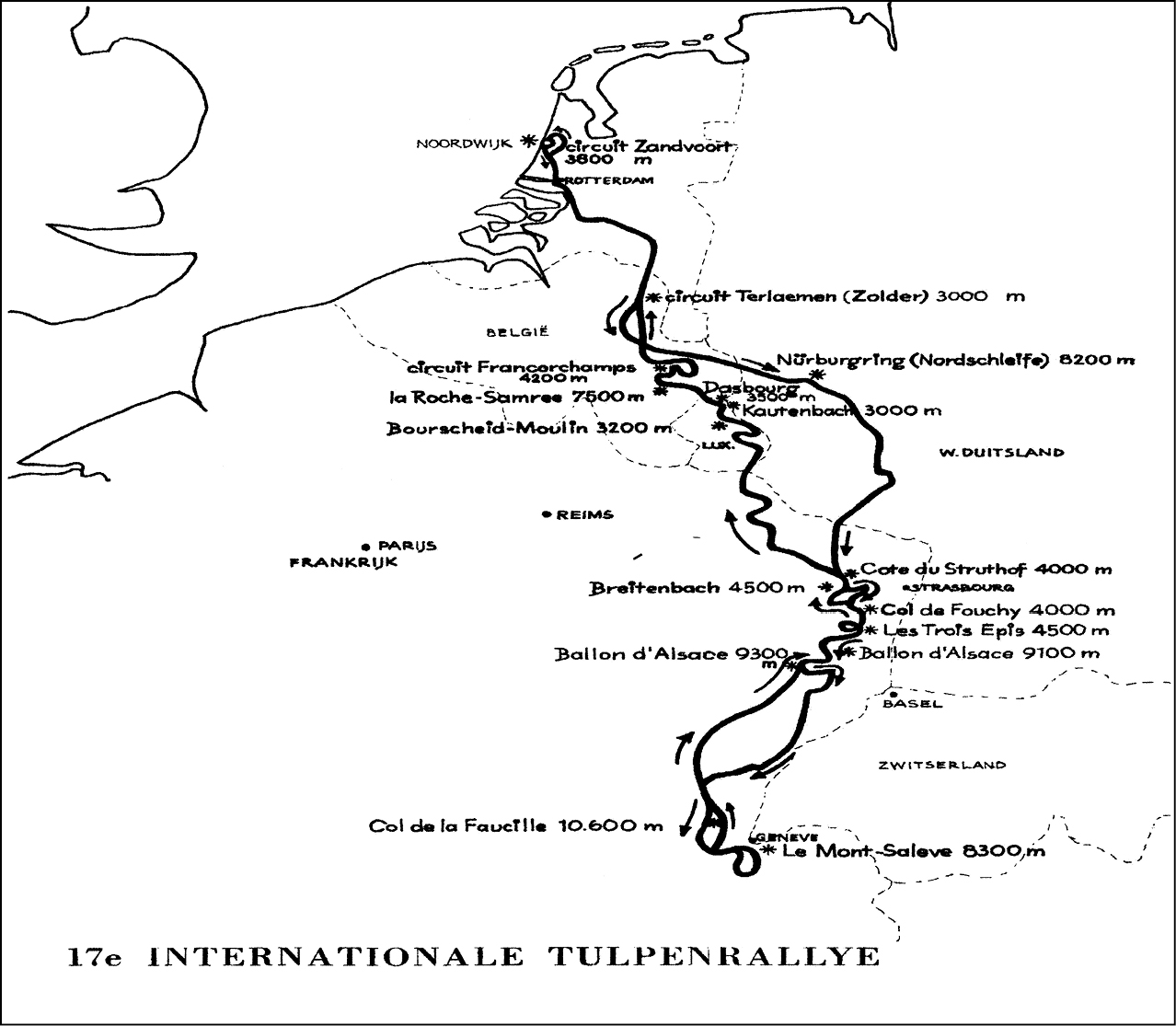

The first Tulip Rally (Tulpenrallye), organised by the Royal Automobile Club of the Netherlands, took place in 1949. It began as an attempt by the Dutch to increase tourism, but over the years became an interesting opportunity for a drive in April/May in comparatively good weather. But 1965 was different: the weather was atrocious.

One hundred and eighty cars began the rally that year. It was a 2,911 km drive through the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany and France as part of the European Championship. Richard Burton, who was in Holland filming The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, waved us off to begin the drive through 19 special stages, 84 checks, as well as special tests. Due to the snow, however, several of the tests were cancelled and only 45 competitors finished the event, the lowest completion rate ever. My teammates Peter Harper and Peter Riley, in their two big Sunbeam Tigers, were among those who were forced to drop out. The trek from Noordwijk and back again saw some of the worst weather ever experienced at that time of the year and many of the cars were left stranded in the snow. This proved to be to the advantage of Tiny Lewis, who came second, and myself, with the biggest handicap, both of us driving a Hillman Imp.

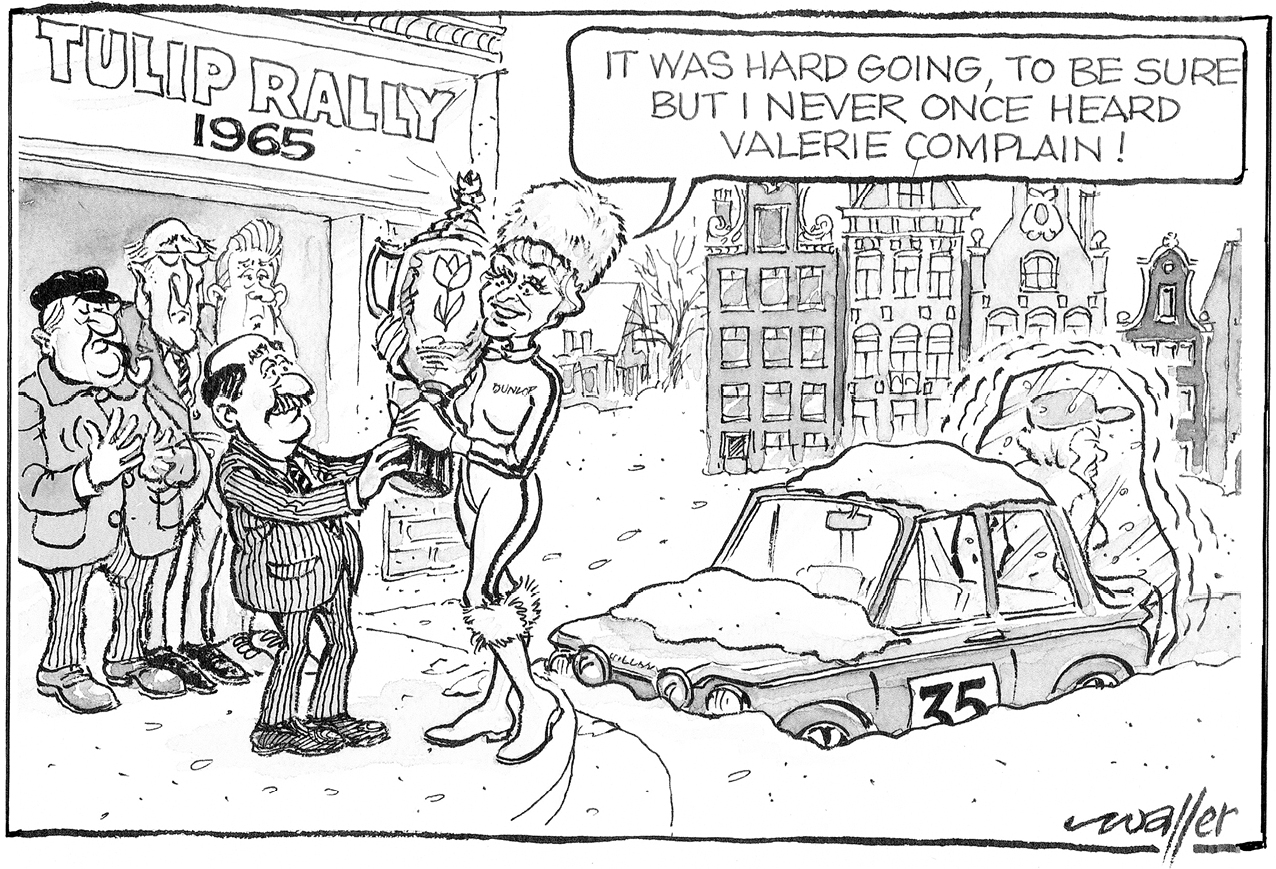

The Imp was like a toy car compared to the Tigers and the Austin-Healey 3000 that the Morley brothers drove and the Cortina of Eric Jackson, but it was light and managed the snow and ice so much better than the bigger cars, although at one point Valerie Domleo, my co-driver, had to get out of the car, sit on the boot lid and bounce up and down to get traction to ascend a particularly slippery part of one of the mountain passes. Poor Val, when she got back in the car it took ages for her hands to thaw out and tears were running down her face – she was marvellous! Rod Waller, an Australian cartoonist, sent me a cartoon of Valerie sitting on the back of the car in a block of ice, so news must have spread far and wide of that endeavour.

Map of the Tulip route 1965

We got stuck at one stage and the car just would not shift. As so often happened, the voice of my father was in my ears: ‘If you can’t move, get the mats out of the car and put them under the wheels.’ I had no mats, but I did have a beautiful suede jacket that I had bought in Spain, so I pushed it in under the back wheels and it worked. Then I sailed off, leaving other drivers pushing and pulling at their cars.

(Waller)

Exhausted by the end of that rally, Valerie and I retired to our room in the beautiful hotel in Noordwijk to have a well-deserved rest. I knew we had done well to get around the road section clean and that we had recorded good times on the speed tests, but until the complicated marking was completed no one knew anything for certain. As we lay on our beds, there was a frantic knocking on the door and someone was yelling for us to get up and come downstairs immediately. We wondered what the matter was, but took no notice and didn’t move until someone else knocked again and told us we had won. We had won the Tulip Rally and didn’t even realise it!

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor were staying at the same hotel and sent me a bouquet of flowers and a lovely letter, which, unfortunately, is no longer in my possession. I lent it to someone to photograph but it was never returned.

In Ireland, my win was reported in the news and my photo appeared on the front page of The Irish Times on 1 May 1965, the caption reading: ‘Miss Rosemary Smith of Dublin who was declared official winner of the international Tulip Rally in Noorwijk, Holland last night’. When I got back to Ireland later that month, a Hillman Imp went on a promotional tour around the country and I drove the last section from Cork to Dublin.

The Coupe des Alpes, or the Alpine Rally, as the British call it, is a punishing event as only half an hour’s lateness means exclusion. If anything goes wrong with your car, it is very unlikely that you will be able to continue. You have to drive up and down those roads in the Alps as fast as you possibly can and just hope the car doesn’t give trouble. Drivers tend to retire, especially in the first few hours, when any fault the car may possess usually comes to light.

The Alpine Rally was one of the most gruelling motoring events I ever undertook. It is run over some of the most demanding tarmac and gravel roads in the world and is a challenge for the most experienced of drivers. I drove in the Coupe des Alpes in 1963, 1965, 1966 and 1967. It went on day and night, no stopping for a rest, driving all the time around the hairpin bends, with horrendous drops over the side.

On one occasion as we came round a bend, I saw some pace notes on the road – obviously the navigator had let them fall out of the car. We got up to the next hairpin, and as we passed I saw a glove on the ground and I swear it was moving, sort of twitching, as it opened and closed. When we got to the top of the pass, the whole rally was stopped and the story was that one of the works’ Lancias had gone off the road, rolled down on a culvert and come out on the road below. The co-driver had his hand out of the window and as the car turned over his hand was amputated at the wrist.

It was on the same rally that my back wheel came off. ‘This is it, we’re out,’ my co-driver, Margaret Mackenzie, said to me as we ground to a halt. We saw the wheel careering down the incline and I clambered down and retrieved it; the donut had broken, which they did at regular intervals with the Imp. When he saw our predicament, a farmer came down the road from his house, yattering away in French. He managed to get the wheel back on with the help of nails and bits of metal that stuck out of the middle of the wheel, making the car look most peculiar. Although we ended up a bit late, we got to the final control by chugging along not on the road but on the promenade in Cannes, scattering people and dogs everywhere.

At the end of the rally, the mechanics took the offending piece off the car, nails and all, had it silvered and made into the most beautiful plaque, which they presented to me some months later in London. The competition manager had said give up (he should have known better), the mechanics knew I wouldn’t, and they must have been proud of my determination. Inscribed were the words: ‘To the girls who kept it going from the mechanics who tried to keep it going’. It was the trophy that meant the most to me and I was heartbroken when it was recently stolen from my house in Sandyford, along with all my silver jewellery. Why anyone would want that trophy is quite beyond me.

That farmer was a lifesaver, and spectators can be very useful, once they don’t get in the way. On one of those Alpines, Anne Hall, who was a really lovely lady and a very good driver, approached one of the many very twisty parts of the pass at a fierce rate and went right over the edge, landing at the bottom of a rocky gorge. I looked down and could see a crowd of people around her. ‘That’s one of our opposition gone,’ I said to Margaret. But I was wrong, because the spectators scrambled down and pushed her up a very steep incline, back on the road and, by some miracle, got her going again.

People are fanatical about rallying and will stand for hours watching the cars go by. In every country, the spectators and supporters are amazing. They come out of farmhouses to help if you need them; some stand on the side of the road, waving and cheering, which is lovely but if you are in a mad rush and there are hundreds of people in the way it can slow you down. You go out to win, and despite notices everywhere saying, ‘Warning to the Public: Motor Racing is Dangerous’ and ‘You are here at your own risk’, people will stand on the very edge of roads and get in the way. Sometimes, unfortunately, they get hurt.

Driving in the Monte, the Tulip and all the other rallies in Europe was great. I had so many new experiences and met some wonderful people, but nothing prepared me for what I would find on the other side of the Atlantic. In the early 1960s the Rootes Group were in financial difficulties and were encountering industrial relations problems in the UK. In 1964 Rootes began to be taken over in stages by the Chrysler Corporation, while I was still under contract. It seemed Rootes and Chrysler thought that the Sunbeam Alpine was a car that would suit the American market and that I would look good behind the wheel for promotion purposes.