CHAPTER 11

Arriving Home

Lewis, Clark, and the Corps traveled down the Missouri River together, just as they had started out. On September 23, 1806, they arrived at the camp near St. Louis, where they had spent the winter of 1803–1804 before their journey had begun. Their appearance came as a surprise to the settlers. Most Americans had given up all hope that they were still alive. But they were very much alive and were greeted as heroes. Clark wrote: “We Suffered the party to fire off their pieces [guns] as a Salute to the Town.”

Sacagawea was one of the heroes. She had rescued Clark’s papers, notes, and scientific samples from the water when their pirogue overturned. She had translated for Lewis and Clark when they bargained for horses with the Shoshone. She had led the Corps for many miles over land she had known as a child.

Sacagawea knew which plants were poisonous and which were safe. The berries and fruit she picked for the men kept them healthy. Sacagawea had mended the men’s breeches and shirts and made them moccasins from animal skins. And Sacagawea, a young mother with a baby, had been a sign to other Indians that the Corps of Discovery came in peace. Maybe the most important of all, she and Pomp had brought a warm feeling of home and family to the soldiers. Just their presence cheered everyone

Later, Clark wrote to Charbonneau that his wife “deserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that route than we had in our power to give her.”

When Lewis and Clark finally met with President Jefferson, they told him about almost two hundred plants unknown to American scientists. They described more than 120 animals unknown until then: bison, bighorn sheep, grizzly bears, prairie dogs, mountain goats, coyotes, jackrabbits, porcupines, pronghorn antelope, bull snakes, terns, trumpeter swans, Lewis’s woodpeckers, steelhead salmon trout, and more.

Lewis and Clark had also learned a great deal about the different Western tribes. They repeated Indian words and phrases. They described Indian clothing, ceremonies, and how and where the tribes lived. They reported which tribes got along and which tribes didn’t.

It must have been a disappointment to Jefferson that the Corps didn’t discover a water route to the Pacific Ocean. Still, in twenty-eight months, their expedition had traveled a round trip of some eight thousand miles. They had survived in wilderness where no white man had ever been before. What the expedition had accomplished was amazing.

The explorers had gathered all sorts of scientific information. Despite the Indians’ presence there, the United States now laid claim to vast Western lands.

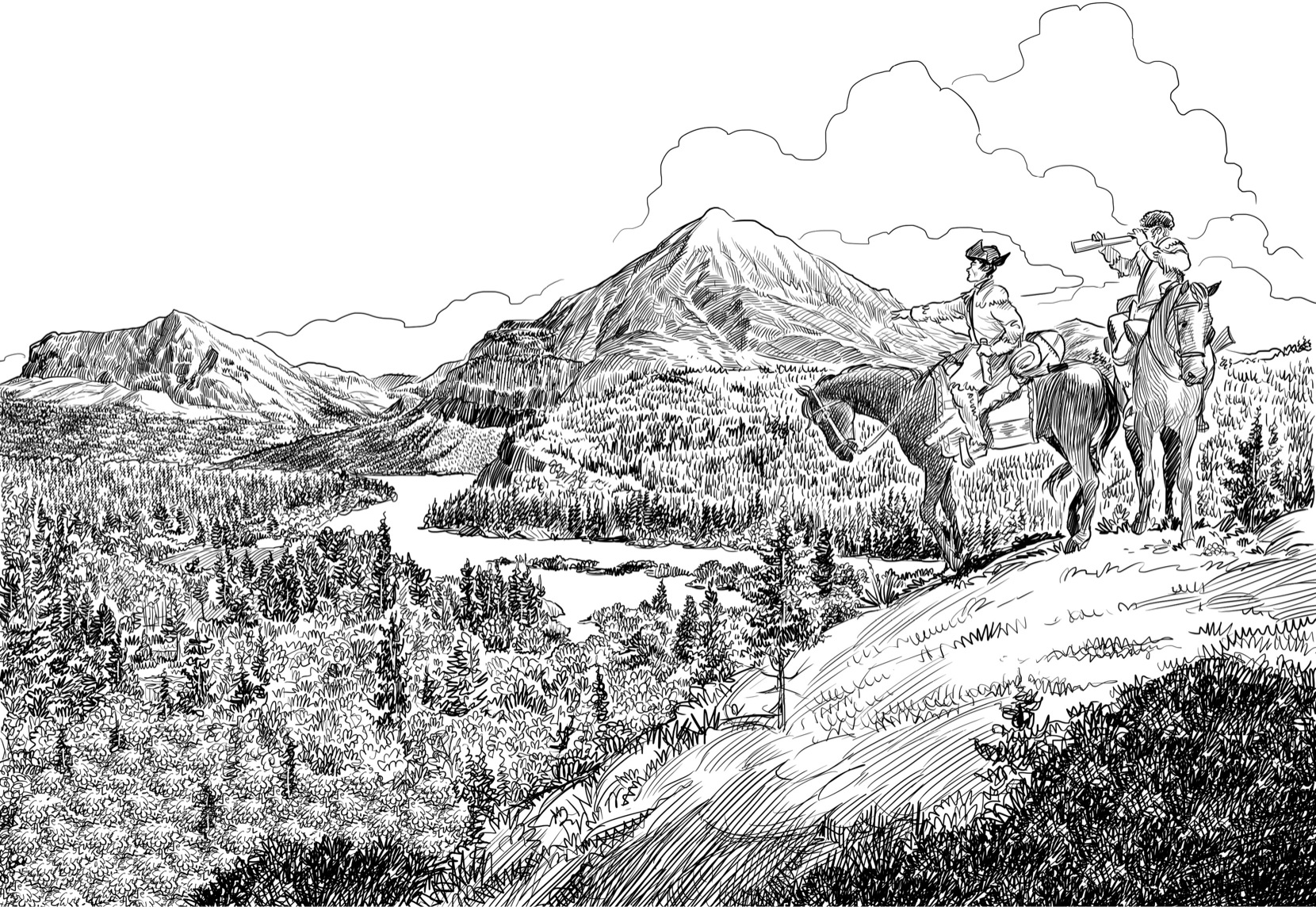

As time passed, thousands of American pioneer families traced the expedition’s trail west to start a new life. Hoping to get rich, traders, trappers, hunters, and explorers also headed west following Clark’s accurate and detailed maps. Jefferson praised the cocaptains’ success: “Never did a similar event excite more joy through the United States.”

The Lewis and Clark Expedition changed the face of the American West forever.