Sinking of the Lusitania

On 7 May 1915, at a time when Britain and Germany were at war, the passenger liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed off the Irish coast. Over a thousand lives were lost and there was consternation in the United States at what appeared to be an unprovoked attack on American civilians sailing on an unarmed passenger ship. It was an undeclared act of war. It was an atrocity, or at least so it was described at the time. The question in many of the cases discussed in this book is who committed the crime. In this case it much more a question of the nature of the crime and whether a crime was committed at all.

The ship was a huge luxury liner, built by John Brown on Clydeside and launched in 1906. With her identical twin sister ship the Mauretania, she was the flagship of the Cunard fleet, sailing on her maiden voyage across the Atlantic in 1907. The two ships were built specifically to compete with the big German liners of the time. Just as the British and German militaries competed with each other in an arms race, the big commercial companies were locked in economic war. There was in effect, before the First World War broke out, already a commercial war going on in the North Atlantic.

The Lusitania and Mauretania were built to be big, beautiful and fast. They were to be a little smaller than the White Star’s Olympic class ships, the sister ships Olympic, Titanic and Britannic, but faster. The speed of the transatlantic crossing was vital to commercial success. The current fastest liner was said to hold the Blue Riband; the Lusitania won the Blue Riband in 1907. Once the White Star Line, Cunard’s main British competitor, announced their Olympic class trio, Cunard decided to add a third ship. She was to be the Aquitania. She would be slower but bigger and more luxurious, and therefore bear comparison with the Titanic.

There was yet another war going on, too. American businessmen were keen to buy into this prestigious transatlantic race, and were not prepared to let the German liners go on winning. The American financier J. P. Morgan planned to buy up all the North Atlantic shipping lines he could, including the British White Star Line. In 1903, the chairman of the Cunard Line, Lord Inverclyde, used these threats, which were in effect threats to Britain’s political as well as commercial prestige, to Cunard’s advantage. Inverclyde lobbied the Balfour government for a huge loan to enable him to build two fast ships. The government agreed, but with the conditions that Cunard remained exclusively British and the two ships met Admiralty specifications. The British government also agreed to pay Cunard an annual subsidy of £150,000 to maintain the Lusitania and Mauretania in a state of readiness for war. This was a very significant step, given the events of 1915, when the official British and American position would be that the Lusitania was not a warship but an innocent merchant vessel. The fact was that the British government intended from the time when the Lusitania’s keel was laid in 1904, ten years before the outbreak of war, to use her for war work. The huge annual payments for her upkeep proved that. The British government agreed to pay an extra £68,000 a year to have the two ships carry Royal Mail.

The ship was launched in 1906, which marked the completion of her hull, and in July 1907 she underwent her sea trials. It was found that when she steamed at full speed violent vibrations were set up in her stern and she was taken back to the yard to have stronger braces fitted in the stern. In August she was delivered to Cunard for service. The White Star’s Olympic class ships were planned but not yet built, so at the time she went on her maiden voyage the Lusitania had the distinction of being the largest ship afloat.

In October 1907, the Lusitania took the Blue Riband from North German Lloyd’s Kaiser Wilhelm II. This brought to an end the German domination of the North Atlantic. Was there now, perhaps, a score to settle in the minds of some German mariners? In 1909 the Lusitania handed the Blue Riband to her sister ship, the Mauretania, but the loss of the Blue Riband from a German flagship to the British Lusitania may still have remained a source of grievance. The Blue Riband would not return to Germany, ironically, until some time after her humiliating defeat in the First World War.

The Lusitania made an average speed of 24 knots on the westbound crossing, or 44.4 km per hour. It was partly confidence in this speed that led to a serious risk being taken in 1915. It was thought she could outrun any U-boat, and steam out of danger. She could comfortably steam 10 knots faster than a submarine, even with one of her boilers shut down. This complacency was misplaced, as it completely overlooked the possibility of an ambush, which is what happened, whether by design or by chance.

The Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat, the U-20. For such a big ship, it sank surprisingly quickly, going down in only eighteen minutes. The huge loss of life was due in part to this rapidity: 1,198 of the 1,962 people on board were drowned.

The rapidity of the sinking is hard to understand. The Titanic was very badly damaged over a large area of her starboard side below the water line and probably her bottom too, but managed to remain afloat, thanks to her watertight bulkheads, for two and a half hours before sinking. Why did the Lusitania sink so quickly? The Titanic and her sister ships had transverse bulkheads, running across the ship. The Lusitania had transverse bulkheads, but she had longitudinal bulkheads too, running along each side, separating the boiler and engine rooms from the coal bunkers that ran along the sides.

When the British commission investigated the Titanic disaster in 1912, they heard evidence that the flooding of bunkers on the outside of longitudinal bulkheads along a significant proportion of the ship’s length could exaggerate listing when they became flooded. This conclusion was reached after the Lusitania was built, after the Titanic had sunk, but three years before the Lusitania was sunk. What was predicted about the effect of longitudinal bulkheads in 1912 is exactly what happened in 1915, and with the predicted disastrous effect: the Lusitania developed an exaggerated list which made it almost impossible to lower the lifeboats on the upturned side because the hull was in the way.

The sinking of the ship turned many Americans from being confirmed neutrals keen to stay out of the European war to being strongly anti-German. It marked a significant step towards bringing the United States into the First World War two years later, which in itself was a major step towards the Allied victory.

The Germans regarded the Lusitania as a legitimate target when they torpedoed it. The British and Americans presented the vessel as a harmless merchant vessel but to an extent the Germans were right. The Lusitania had been built to Admiralty specifications, so that her decks were structurally strong enough to support deck guns if required. The Lusitania may not have been a warship at the time when she sank but her design meant that she could be requisitioned and quickly converted into an Armed Merchant Cruiser. On the other hand, the Lusitania had not been so requisitioned, for economic and practical reasons. She was a big ship, used far too much coal compared with a custom-built cruiser and would have put too many crewmen at risk. As a result the British government were more interested in converting small liners into AMCs. The large ships were either left unrequisitioned or used for troop transport or used as hospital ships. The Mauretania became a troop transport. The Britannic became a hospital ship. The Lusitania conspicuously remained a transatlantic passenger liner.

On 4 February 1915, Germany declared that the seas surrounding the British Isles (ie Britain and Ireland) a war zone. From 18 February onwards any Allied ships would be sunk without warning. This meant that British ships might be sunk, though not American, because the Americans were still neutral. The British Admiralty issued the captain of the Lusitania with instructions on how to avoid submarines when the ship arrived in Liverpool on 6 March. The seriousness of the danger to the Lusitania was fully understood at the Admiralty, and two destroyers were sent to escort her, HMS Louis and HMS Laverlock; the Q ship HMS Lyons patrolled Liverpool Bay. Unfortunately Captain Dow did not know he was getting a naval escort, thought the destroyers might be German vessels and took evading action. He nevertheless arrived safely in Liverpool.

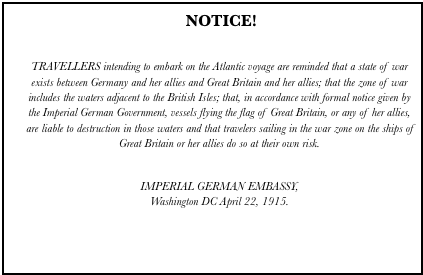

The Lusitania left Liverpool on 17 April and arrived in New York on 24 April. Some German-Americans planning to return to the United States were unsure about travelling on the Lusitania because of the possibility of U-boat attack and consulted the German embassy. The advice from the German embassy was not to travel on the Lusitania. The German authorities were once again clearly signalling that they saw the ship as a military target, well before her final sailing. That final departure, from Pier 54 in New York, came on 1 May 1915. Before she sailed, a newspaper warning was published next to the advertisement for the ship’s never-to-be return voyage, advising people not to travel because of the danger of U-boat attack. This was a reminder of the warning issued by the German Embassy in Washington on 22 April.

The Lusitania’s fifty-eight year old captain, Bill Turner, made light of the danger. He told one passenger the Lusitania was ‘safer than the trolley cars in New York City’. Shortly after embarkation, three German spies were discovered on board. They were arrested and detained.

As the Lusitania approached British waters, the British Admiralty tracked the movements of the German U-boat U-20 by picking up its wireless signals. The U-20, captained by Walther Schwieger, was off the west coast of Ireland and moving south, as if to intercept the Lusitania. On 5 and 6 May the U-20 sank three ships near the Fastnet Rock. The Royal Navy sent a warning to all British ships, ‘Submarines active off the south coast of Ireland.’ Captain Turner was given this message twice on the evening of 6 May. Turner responded by closing the watertight doors in the bulkheads, doubled the lookouts, ordered a blackout at night and had the lifeboats swung out on their davits so that if they were torpedoed the boats could be lowered at speed.

At eleven o’clock in the morning on 7 May Turner responded to another radio warning by altering course to the north-east. He assumed U-boats would be more likely to patrol the open seas, less likely to come close inshore. The Lusitania, he thought, would be safer steaming close to the Irish coast. Captain Schwieger was about to take the U-20 off duty. The submarine was low on fuel and he needed to take her home. He was taking the U-20 at top speed on the surface when, at one o’clock, he saw a ship on the horizon. This is his diary entry;

Ahead and to starboard four funnels and two masts of a steamer with course perpendicular to us come into sight (coming from SSW it steered towards Galley Head). Ship is made out to be large passenger steamer.

It was too good an opportunity for a conscientious U-boat captain to miss. He ordered his crew to take up battle stations and took the submarine down to thirty-six feet.

The Lusitania was heading for the port of Queenstown when she crossed right in front of the U-boat at ten past two. It was an ambush by chance. When his U-boat was just 700 yards away from the Lusitania, Schwieger gave the order to fire one torpedo, which hit the Lusitania right under the bridge and blew a hole in the side of the ship. Then there was a much bigger second explosion, which blew out the starboard bow. The two explosions have puzzled historians for a long time. There were definitely two explosions, but Schwieger’s log shows that he only fired one torpedo. Some have argued that, in the wake of the international condemnation that followed the sinking, the German government doctored Schwieger’s log to make it look as if he only fired once. Firing twice might have made it look like a massacre, especially since the ship sank so fast. On the other hand, the accounts of U-20 crew members agree with Schwieger’s log entry: only one torpedo was fired. In fact it now looks as if the torpedo explosion on its own would have sunk the ship; the off-centre large-scale flooding would have caused the ship to capsize. All the ships’ portholes were open, for ventilation, and that too would have speeded the sinking as the ship heeled over.

The wireless operator sent out an SOS straight away. Captain Turner gave the order to abandon ship, though this was difficult. The torpedo damage had made the ship list sharply and the damage caused by the second explosion made the bow sink under the water; at the same time, the ship was still moving forward at some speed. Launching the lifeboats under these conditions was difficult and dangerous. The lifeboats on the starboard side were swinging well away from the ship, making it difficult for passengers to step onto them. On the other side of the ship it was possible to get into the lifeboats quite easily, but hard to lower them. The hull plates were fastened together with big rivets and as the port side lifeboats were lowered they caught on the knobbly rivets and were in danger of being broken apart by them.

Some of the lifeboats overturned before they reached the water, spilling passengers into the sea. Some reached the water and were then overturned by the convulsing motion of the ship. Some, as a result of the incompetence of the crew, crashed onto the deck and killed passengers. Following the Titanic disaster, there were more than enough lifeboats for the number of people on the ship, but of the forty-eight lifeboats on the Lusitania only six reached the water and stayed afloat.

Captain Turner saw that land was in sight – in fact a six-year-old boy watched the entire tragedy unfold from the Old Head of Kinsale, eight miles away – and tried to take the ship towards the coast to beach her. All around him there was panic and chaos. Captain Schwieger watched this through his periscope. It seems not to have occurred to him to go to the aid of the passengers and crew of the Lusitania. Perhaps he regarded them as fools for sailing in the first place, in the face of all the warnings from Germany. At twenty-five minutes past two, he decided he had watched enough of the sinking of the Lusitania, dropped his periscope and headed for the open sea. In his war diary he implies only that he regretted being unable to fire a second torpedo.

Since it seemed as if the steamer would keep above water only a short time, we dived to a depth of twenty-four metres and ran out to sea. It would have been impossible for me, anyway, to fire a second torpedo into this crowd of people struggling to save their lives.

Captain Turner stayed on the bridge until it dipped under the water. He saved himself by grabbing a floating chair. The ship was sinking bow-first in shallow water. Her bow hit the seabed and she turned right over onto her side before sinking. The boilers blew up, one of the explosions causing the third funnel to collapse; the other three funnels snapped off one by one. The liner sank at twenty-eight minutes past two, sucking people, debris and water down with her. She hit the bottom and two minutes later there was a great upwelling of water, debris and people. In the event, 1,198 people died, including nearly a hundred children.

The second explosion was responsible for the ship sinking so fast, and therefore raising the death toll. One theory is that the Lusitania was carrying arms, which not only caused the second explosion but justified the German view that the ship was participating in the war effort. On the other hand there is only evidence from the wreck site of small arms ammunition (15,000 bullets), which could not have caused the explosion. Schwieger himself noted a possible cause in his war diary.

Torpedo hits starboard side right behind the bridge. An unusually heavy explosion takes place with a very strong explosion cloud (cloud reaches far beyond front funnel). The explosion of the torpedo must have been followed by a second one (boiler or coal or powder?).

The huge force of the first explosion may have stirred up a lot of coal dust in what must have been largely empty coal bunkers along the outside of the longitudinal bulkhead. It is well known that a mixture of coal dust and air makes a highly explosive gas. This, exploding on the outside of the longitudinal bulkhead could have blown a big hole in the ship’s starboard bow.

Others believe this was almost impossible because the initial torpedo explosion would have sent huge quantities of seawater sideways into the coal bunkers. The coal dust would have been instantly saturated. A likelier alternative is an explosion in the steam-generating plant, as immediately after the second explosion the forward boiler room filled with steam and the steam pressure dropped dramatically.

There was outrage in Britain and the United States. The US government was indignant because 128 Americans had been killed by an act of hostility at a time when their country was neutral. In Britain, there was a hope that the United States would abandon neutrality and declare war on Germany. Some conspiracy theorists have even proposed that the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, set it all up. He arranged to sabotage the Lusitania specifically in order to force the Americans into the war. But there is no evidence whatever to support this.

President Woodrow Wilson still did not want to take that step, not least because many Americans were of German origin. Instead he sent a formal verbal protest, for which he was branded a coward in Britain. In fact Wilson’s restraint was remarkable in view of the wave of anti-German anger in America. The American reaction was so strong that the German government decided to impose a ban on U-boat attacks against large passenger vessels; the Germans did not want to goad the Americans into becoming a British military ally.

In Munich, in August 1915, the metalworker Karl Goetz struck a commemorative medal to satirize Cunard’s greed. The German view of the Lusitania was that she was smuggling contraband under the cover of American neutrality. The medal carries the critically incorrect date of 5 May. British intelligence got hold of a copy and saw a way of turning its propaganda value upside down. The wrong date, possibly just a mistake, was made to imply that the sinking of the Lusitania was a premeditated crime, a crime in cold blood. Selfridge’s were commissioned to make a quarter of a million exact copies of the medal, but with English lettering. They were sold in aid of the British Red Cross. Goetz realized too late that he had made a terrible mistake and issued a corrected medal bearing the date 7 May. After the war he admitted to having made the worst propaganda blunder of all time.

It is impossible now to find out what Schwieger thought he was doing – possibly, like so many other officers in wartime, just carrying out orders – as he died not long after the sinking. He was killed two years later when his submarine, the U-88, struck a mine. In the wake of the sinking of the Lusitania, he was branded a war criminal in Britain and the United States. But did he really commit a crime? While it might be argued that the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese was unprovoked, an act of undeclared war, the same could not be said of the attack on the Lusitania. The Lusitania was a British ship; most of the personnel on board were British; Germany and Britain were formally at war; Germany had declared the waters round Britain to be a war zone; Germany had given several very explicit warnings that U-boats would attack British shipping, including a specific warning to those thinking of sailing on the Lusitania on its last voyage.

In the end, the British authorities believed they could get away with sending the Lusitania through seas patrolled by U-boats because she was so much faster than they were. She could outrun them. Why the Admiralty did not pause to consider the possibility that a U-boat might simply lie in wait off the Old Head of Kinsale, perhaps even stationary, and fire a torpedo into the side of the Lusitania as she passed, is beyond comprehension. There is the question of escorting vessels. The Admiralty for some reason took the precaution of sending a naval escort to accompany the Lusitania from the Irish Sea into Liverpool on an earlier voyage, but not to help her through the far more dangerous waters off the southern coast of Ireland. It could be argued that the Admiralty showed criminal negligence in failing to provide a very obvious target for German submarines with an escort.

But, even if the firing of the torpedo was not a crime, and even if the sinking of the Lusitania was not a crime, Captain Schwieger remains open to criticism. As he lowered his periscope, having seen enough, he knew that a thousand people were struggling for their lives in the water. He made no attempt to help them. It is also questionable whether he just happened to be in the right place at the right time by chance. Given that the sailing time of the Lusitania was public knowledge in New York, that her route was publicized, and that there were both a German embassy and German spies in New York, the German naval command would have known almost to the minute when to expect the Lusitania’s arrival in Queenstown. I firmly believe the U-20 was directed there, to wait for the Lusitania. In the wake of the tremendous wave of angry condemnation, this cold, calculated and premeditated ambush had to be presented as a U-boat captain’s lucky break.