XVII

As I went to Walsingham,

To the Shrine with speed

Met with a jolly palmer

In a pilgrim’s weed.

Now God save you jolly palmer!

Welcome lady gay,

Oft have I sued to thee for love,

Oft have I said you nay.

‘Walsingham’

Popular ballad

From time to time I would visit the Fleet. It was another world, where the only talk was of the Catholic faith and its re-establishment by the King of Spain.

I understood now how Cardinal Allen could so firmly believe that two-thirds of the English were crypto-Catholics, for the Queen was surrounded by a surprising number of ‘papists’, out of all proportion to the number of Catholics in the land. It may not have been two-thirds, but my mother was right to claim that as many Masses were said at the English court as at the royal court of any country on the Continent.

It must be said that Catholics were nowhere so safe as at court. This I observed with my own eyes. In consorting with the Earl of Southampton, I enjoyed the same protection as he. And I saw that the way to stay out of trouble was to avoid politics. Provided a man kept his beliefs to himself and refrained from voicing a desire to see a Catholic King on the throne, nobody interfered. My father had not understood this, which was why he found himself with his back to the wall.

There was a bowling green in the Fleet gardens, where the Catholics met and debated vigorously as they played. They made my head ache with their litany of cruelties committed against Catholics by the ‘heretics’. One does not excuse the other, but the Inquisition tortured heretics too, and burned them alive, Protestants first and foremost.

My twenty-year-old head span with all this, but I said nothing, for I bestrode two worlds. Deep down, I shared Marlowe’s and Southampton’s view: there is no sin but ignorance.

My father was most troubled because Abbot Cornelius had been arrested just when I was preparing to leave. He turned pale every time Phillips brought him a message.

I saw Benjamin Tichborne again, the fellow who was to marry my sister Margaret, and was told that he was a good boy whose cousin had wed my sister Mary – but what did I know if my sister Mary had made a successful marriage? Decidedly, there was something about this Tichborne that offended me. And then there was Charles de Troisville, who might still love my sister; I would have to warn him. To my great regret, I never saw Margaret herself, for she was staying with Mary.

Phillips was as busy as ever, coming and going from the Fleet, where there were about thirty Catholic families and which, paradoxically, drew many Jesuits, come to confer with my father.

They were all a little wary of me and never discussed their business in my presence, restricting themselves to very general declarations when I was there. This was a relief, and it proved the absurdity of the situation, for even among Catholics we were split into two camps, the Jesuits (including my father) and the non-Jesuits, the so-called secular priests, who were less arrogant and less conspicuous. Increasingly, voices were heard from both this latter camp and the wider Catholic laity, demanding that Rome be less inflexible. They would have liked to swear allegiance to the English Crown while also adhering to their faith. In truth, that was all anyone demanded of them, and Southampton was the living example of it. But Rome wouldn’t budge, chiefly because of the pressure applied by Spain and the Jesuits. Elizabeth was a usurper and therefore unworthy of fealty. Consequently, attitudes in London hardened.

‘My son,’ said my father solemnly, ‘you will soon reach your majority. I would like to give you enjoyment of all our family’s means, which are considerable, but circumstances have wished otherwise. God has demanded a great sacrifice of us, and in order not to profane His house, we have had to abandon our terrestrial goods. Our enemies enjoy our revenues without scruple. Be proud to be poor: it is for the good cause, and never forget that you are a Tregian, a Catholic, one of Christ’s soldiers. Come, let me bless you.’

I knelt. He placed a hand on my head and appealed to the Lord.

‘Amen,’ I concluded, between gritted teeth.

‘I would like you to go to Spain, my son, and take a message to His Most Catholic Majesty, whom we all revere and who will show you his gratitude.’

‘My father, I am truly sorry, but I promised Cardinal Allen to return as quickly as possible and I have tarried for too long already. Several of us are busy with a complete revision of the Douai Bible, and the Cardinal insisted I return soon to continue my work on it. There is also his failing health; he needs his entire retinue.’

I persuaded my father, in the end, and he found somebody else to go to Spain.

During my stay, I hardly saw Giuliano, who had taken his role of steward most seriously and had set off to enquire after my various interests. Jack informed me that he had returned to Muswell several days before, and there I went after seeing my father. It seemed to me that the sun failed to shine a single day that year, and it was raining again as I rode slowly up Crouch Hill thinking about what my father had just told me:

‘You shall be heir to all of the estates one day. If it were to cost you your soul, then better to lose everything. But it is your duty to yourself, your sisters and brothers, and to your descendants, to make every attempt to recover them. Promise me – promise your ancestors – that when the time is ripe, you will do all you can to reclaim the title of Lord of Wolvedon and the lands of your forebears.’

In a flash I fancied I saw Jane Wolvedon’s eyes.

‘I promise you, father.’

At Muswell, my grandmother addressed me in a peremptory tone:

‘There is no question of your departing by yourself. Jack will accompany you, along with the groom Joseph.’

‘That’s impossible, madam. I’m living off charity in Rome.’

‘I am not asking you to pay them; I will cover that.’

‘But their board and lodging, I wouldn’t know how to…’

‘Don’t be as stubborn as your father. I am not your mother and will not yield to a Tregian’s whimsy. I have said that you shall not depart like a ragamuffin, and I will not be argued with.’

‘Madam, if I really must, then I agree to take Jack, but I have no need of a groom. In Rome, I don’t even have my own horse.’

‘That is nothing for a grandson of the Baron of Arundell and the Earl of Derby to boast about.’

We reached a compromise: she kept the groom and I took Jack, who needed no encouragement. Naturally, he would also take care of my horse as required. Naturally, he would be devoted to me, body and soul. Naturally, I would be served like a king. Jack had such clownish qualities, I should have handed him straight to Master Shakespeare, but if I were to have a valet at all, I had rather it were him. Lady Anne had not chosen him by chance. This peasant lad from Muswell was as alert and trusty as he was droll.

We were not out of London yet when Giuliano and I placed ourselves either side of Jack and spoke to him:

‘Jack, you now serve Master Tregian.’

‘Assuredly, sir.’

‘My happiness is your own.’

‘Assuredly, sir!’

‘So your loyalty is to him, and you report to nobody but him.’

‘But, that goes without saying, sir.’ He was worried now.

‘How would I know that you aren’t a spy?’

‘A spy? Me? And for whom?’

‘Oh, there are a thousand possibilities. Lord Burghley. Sir Topcliffe. Father Parsons. And so forth.’

He gave a nervous laugh.

‘Sir, I know none of those gentlemen, and I swear on my soul that from this day forth I shall have no master but you. I will report to you alone, and as far as all those who might question me are concerned, I know nothing of your affairs. I can play the idiot as well as any man.’

I left London with a heavy heart. It had not been possible for me to take leave of the Queen. Lord Burghley was unwell and so had me received, albeit discreetly, by his son Robert, a charming man – short and hunchbacked, with an intelligent glint in his eye.

‘Master Tregian, Her Majesty holds you in affection.’

‘I thank you, sir.’

‘Yours is an unstable, dangerous life.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘May I offer you my support?’

‘I prefer your affection, sir. I do not wish to feel I have been bought.’

He laughed.

‘You already have my affection, Master Tregian. Return whenever you wish. I shall not forget you.’

I tore myself away from Southampton House and its merry company, from Thomas Morley and Giles Farnaby too, with whom I had spent so many long nights making music. Where would I find such entertainment and glad company now? Thomas Morley was a great believer in writing things down and he advised me to keep a ‘common book’, a personal collection of scores.

‘You’ll lose that humble-jumble of papers and little notebooks you carry around with you.’

I adopted his idea, procured myself the necessary materials and began immediately, copying only the pieces I could play on the organ and the virginal, and for which I needed no accompaniment. I must say that Morley and Farnaby had filled my head with so many melodies that I would not have remembered them all had I not set them down.

I began my collection with some of Bull’s superb reworkings of Walsingham, a ballad we had sung when we were children:

As ye came from the Holy Land of Walsingham

Met you not with my true love by the way as you came?

How should I know your true love that have met many a one,

As I came from the Holy Land, that have come, that have gone.

Our little company spent the first night of our journey at the Mermaid Inn in Salisbury. Jack and Kees, Giuliano’s valet, ate and drank in a corner of the main room. Giuliano and I sat in a private room and were served what I have always considered a quintessentially English meal. There were meats in abundance, sauces of every kind, pancakes and baked apples, washed down with the Mermaid’s delicious ale: everything to appal an Italian. I pushed the food around my bowl, lost in thought.

‘You should eat, instead of sifting all those gloomy thoughts in your head.’

Giuliano was thirty-five, still had a head of black curls and only the merest glint of silver in his short beard. His agility and good humour were intact, and the few wrinkles round his eyes only served to strengthen the feeling he had always conveyed: that when he was there, no trouble would befall me, and all problems would be solved by his capable hands. I had grown so used to consulting him about everything from boyhood on that he had become a brother, father and companion to me, all at once. Strictly speaking, he was my servant, as was Jane, who had been my nurse, but I never grew accustomed to seeing them in that light. They were both children of great lords, and you could see it in their bearing.

‘So you’re fasting, are you?’

Giuliano’s words tug me back to reality.

‘No, no. I was wondering what I would do without you.’

‘You would live. A little less comfortably, perhaps. Talking of which, I have undertaken some enquiries. You know that your father is not quite as impoverished as people say.’

‘My father? How so?’

‘Firstly, praemunire orders the seizure of two-thirds of your estates, not the entirety.’

‘Right, and… ?’

‘Everything your family owned in Cornwall has been sequestered.’ He left a dramatic pause. ‘Except that the Tregians also have estates in Devon and Dorset.’

‘Ah? A third?’

‘Not quite, more like a quarter or a fifth, according to my information. It would be possible to bring a case against George Carey to force him to return the excess seizures. But given your father’s fervently papist attitude, in which he is quite resolute, it would be a waste of time in my view. I must say, poor devil that I am, it is strange to see how much your father has lost interest in his affairs. Your grandmother Catherine fought tooth and nail until her dying breath to recover her pension of sixty pounds. Your father, however, lets hundreds of pounds a year be stolen from him without batting an eye.’

‘He has no head for business.’

‘To say the least. Just imagine: your grandfather John not only doubled the family fortune but succeeded in living peacefully under Henry VIII, his Protestant son Edward VI, Mary the Catholic and finally Elizabeth, a period of nearly twenty years. He not only had a head for business, but also a subtle way in his dealings with others. Then he died, his son took over, and disaster followed shortly thereafter.’

We look at one another, sigh and shrug in unison. My bed is made; now I must lie in it.

Two days later, the notary solemnly hands me the title to the property Thomas had left me. It has been drawn up in such a way that it would be practically impossible to dispossess me of it. The estate is called Tregellas, like Thomas himself.

We spend one night in the house which holds so many memories for me. Two servants and the family of the tenant farmer maintain the place as if I might return to live there any day. They call me Master Francis as if they had known me for years, and they speak of me as ‘Master Tregellas the Younger’. The beds are made up, the rooms are aired and scrupulously clean. The temptation to stay makes me dizzy.

Still, we bid farewell to England the following day, on the dawn tide.

I have never regretted leaving so much as I did that morning. Over those last few weeks, I lived in a world that was my own. I was no visitor but felt at home for the first time in a very long while.

The first thing that strikes me when I see the Cardinal is his cadaverous face.

Nicholas Fitzherbert, Roger Bayns, William Warmington and Nicholas Bawden are there too. We are soon engrossed in one of those discussions of which the Cardinal is particularly fond.

I hardly pay attention to his words, so fixed am I on his sunken eyes, deep as wells. He is close to death.

The next day, I take up my work on the Bible again. Titus, Giuliano’s nephew, remains in the kitchens, just in case.

‘I’ve done my best, but I reckon they’ve changed the poison, or the method.’

Titus has told no one, of course, but to my great amazement, rumour is rife that an attempt has been made to poison the Cardinal. At first I think this might help us – surely it will protect Allen if everybody suspects something. Finally, though, I understand the talk must be a stratagem: a connection has been observed between my presence and Allen’s state of health, and fearing I might say something, the plotters have preferred to spread a controlled rumour. If things now take a bad turn, I can always be accused of being the poisoner myself.

Meanwhile, whether by poison or by sickness, the Cardinal’s health grows visibly worse.

I am on duty one evening. It is very hot and I have opened my doublet to breathe easier. Suddenly, the Cardinal is standing before me – I hadn’t even heard him approach.

I stand, bow, mutter an apology and button up.

‘Call for some men to accompany us; I would like to take a walk with you.’

Once outside, he speaks to me first about King Henri IV, whom he calls ‘that Navarre’. He has done all he could to persuade Pope Clement to refuse the French king’s conversion. He has written, pleaded, made speeches; he is convinced ‘that Navarre’ will do as Henry VIII of England had done, and that France will follow England’s fall into heresy. Allen feels that the French throne would be better with any other prince on it than a Bourbon.

I do not reply and succeed in holding back a certain irritation. After all, he is talking of a man who has been a friend to me. I try to think about something else.

A change in his tone of voice pulls me back to the present moment.

‘You know, the work you’re undertaking on the Bible is most precious. You are extremely able, and your mastery of Latin and rhetoric is exceptional.’

I bow in silence. In the half-light of dusk, his eyes bore into me.

‘I have always wondered why you never assented to your father’s wish that you take Holy Orders.’

Now I am on the alert. It is rare for the Cardinal to ask such a direct, personal question.

‘But, Your Eminence… How to put it… When the idea was proposed, I had already chosen another path. And I still hope to manage my family’s estates one day.’

‘Let me be plain, Master Tregian: what do you think of the Catholic religion?’

Alarm bells ring in my head. This man can send me to the Inquisition at any time. Perhaps he has drawn me out of the house just to have me arrested discreetly.

‘Your Eminence!’

‘Oh, I can see very well how devoted you are to me, and that you watch over me with filial care. They tried to get me to believe you were poisoning me, little by little, but I know that’s impossible.’

‘Your Eminence!’

This time, I fall to my knees before him, my cheeks wet with the tears that come pouring now, unchecked.

‘Your Eminence, I love you like a father!’

He bids me stand up.

‘My son, you don’t waste time with excuses; I like that. I sometimes worry about your piety, for you are most discreet in all matters except when you sit down to play music. But I have never doubted your loyalty. And I have noticed your concern for me.’

I struggle to remain silent.

‘You know, don’t you, that attempts have been made to poison me?’

‘Your Eminence, I assure you…’

A silence.

‘So, you will tell me nothing; that is most politic of you. Byas thinks that if I am being poisoned, then it is with the water I drink at the Vatican Library. So he always pours it for me after fetching it himself. That has not prevented me from falling sick. But perhaps I owe my ill health to God’s will rather than to poison.’

‘I wish you long life, Your Eminence, and I beg you to use me as you see fit.’

‘As long as I don’t wish to make a priest of you, isn’t that so? No, no, protest not. But I regret it. You are a gifted orator. What a preacher you would have made!’

We walk home through the dark.

Now that I know John Byas is aware of the poisoning, I am able to share the duty of protecting the Cardinal with him. Titus continues to watch over the kitchens. None of it is any use.

The Cardinal is soon confined to bed. In October 1594, he dies.

All of us are around his bed. We hear the churches of Rome ringing Matins. The Jesuits, led by Alfonso Agazzari, have attempted to block our admittance to his chamber, but the Cardinal has interceded with unsuspected energy. Once he has perceived that he is doomed, and in spite of his terrible pain, he sets about dictating letters to the great and good of this world. He writes to the Pope to warn him against false friends, to the King of Spain to request forgiveness for the errors committed in his service. Father Champion and Father Ingram, whom he knows well, have been hanged in England over the summer. He prays for them to intercede so that God might welcome him to Heaven.

‘My greatest sorrow is to have been responsible for sending so many to prison, to persecution and death. May God have mercy!’

We approach him one by one, and he gives us his blessing.

When I kneel by his bed, he takes my chin and pulls my head towards him.

‘Leave immediately, you are in danger,’ he whispers to me. Then he kisses my forehead. ‘They know that you endeavoured to save me. ‘Ego te benedico… ’ – and he traces a cross on my forehead.

Father Warmington says Mass at the foot of the bed. The Cardinal expires shortly after the Communion, his face serene and free of pain.

I would have left within the hour, had the decision been mine. But the repercussions of Allen’s death echoed throughout Rome and would soon reach Spain and England. Allen had been in conflict with the Jesuits, but, apart from a few among them, everyone loved the Cardinal, whose greatest gift was perhaps that he knew how to kindle devotion.

He was barely cold, and still lying in the chapel of the English College, as he had requested, yet the fight to succeed him was already under way. The new Cardinal must be English. There was no written law to that effect, but the King of Spain wished it. All that was lacking was a man capable of filling the position.

Nobody desired to give the funeral oration. For two days I watched the deliberations, distanced from them like a spectator at a play. It had nothing to do with me, and I was already wondering whether to halt my journey at Mantua to attempt to meet the great Monteverde, when Gabriel Allen, the Cardinal’s elder brother, came to find me. He lived in Rome, along with other members of the Allen family, but I had rarely seen him and only ever from afar: we didn’t really know each other.

‘Master Tregian,’ said Gabriel, ‘the Cardinal loved you dearly and held your mastery of Latin in special admiration. I think he would have wished you to give the funeral oration.’

‘Me?’

Nobody wished to accept the task – a single word out of place could prove highly dangerous in these fickle times.

‘Not only do you speak Latin as if it were a living tongue but you are an excellent orator.’

‘I thank you, sir, but it is too weighty an honour. And since the funeral is tomorrow, how would I… ?’

‘I shall assist you. Nicholas Fitzherbert has said he is also ready to work with us. We would not wish to leave this oration to the Jesuits of the English College.’

There was a steely determination in his usually kind face. Given the position I was in, there was no more risk in delivering the speech than there was in keeping quiet.

‘I accept. But let’s set to work immediately.’ I sent Jack to fetch Nicholas and some writing supplies.

‘And something to eat and drink while you’re at it. We’ll be working all night.’

‘Very well, sir.’

Jack had settled so happily in Rome you would think it was but three leagues from Muswell. In just a few months, he spoke the language quite intelligibly and was perfectly at home. He soon returned with quills, paper, penknives, sand, ink, wine, bread and cheese; and was followed closely by Nicholas Fitzherbert.

‘Don’t you wish to give this funeral oration yourself? You attended the Cardinal for nearly ten years and knew him better than anyone.’

‘I am an execrable orator. But I write well. I see you have everything we need.’

We sat down, discussed the matter and, after several failed attempts, we finally began to compose the Oratio funebris.

Utinam intra unius aulae provatos parietes se contineret causa doloris!…

We recounted the life of William Allen. I agreed with what I was to say, despite my reservations: the Cardinal had been a kind man, incapable of meanness, one who never served his own interests. Even when he was ready to deliver England to Philip II of Spain, it had been for the greater glory of God, and he had never understood how he might be accused of treason. He never doubted for a moment that, once the country had returned to Catholicism, the King of Spain would withdraw and leave it to the English. Eloquent, subtle in his dealings with others, replete with knowledge and generous too, I had tears in my eyes as I listed his qualities. I am sure that God welcomed him with open arms.

We finish as dawn is breaking. I just have time to change my clothes.

‘What are your plans, Master Tregian?’ asks Gabriel.

‘To leave, sir.’

‘That’s good. It was the Cardinal’s wish. Here’s a pass so you may leave Rome without hindrance. Don’t tarry. We shall cover your departure as long as we can.’

Jack has spent all night trimming quills and dipping them in ink, but is as alert as ever.

‘Jack, do you have the strength to prepare our baggage?’

‘Our baggage, sir? To go where?

‘To leave Rome before I am poisoned, or someone picks a quarrel with me, or my horse makes a lethal stumble, or I don’t know what…’

‘Ah, I see, sir. As soon as you get out of the church?’

‘Yes, as soon as I get out of the church. We have a pass. And let’s not take too much baggage, so we aren’t noticed. Leave whatever you like except my music.’

‘Very well, sir.’

The church of the Trinità, adjoining the English College, is full of cardinals, ambassadors – the Spanish ambassador has pride of place – and priests, as well as many lay-people. It is a solemn ceremony.

I try to construct my pronouncement of the Oratio funebris as one would compose a song in three voices, with one voice questioning, a second answering and a third commenting.

‘… Quid multa? Haec suprema vox – oportet meliora tempora non expectare, sed facere – ita alte in Cardinalium… ’ and so on. Ours is not to wait for better times, but to provoke them. This notion of the Cardinal’s, told me by Nicholas, and which I share with the audience, seems to be dictating my course of action. I must take my life into my own hands.

That very evening, Jack and I go to sleep in an inn beside Lake Trasimeno, on the way to Mantua.

Book II

Between Earth and Heaven

Heaven and earth and all that hear me plain

Do well perceive what care doth cause me cry,

Save you alone to whom I cry in vain,

‘Mercy, madam, alas, I die, I die!’

…

A better proof I see that ye would have

How I am dead. Therefore when ye hear tell,

Believe it not although ye see my grave,

Cruel, unkind! I say, ‘Farewell, farewell!’

‘Heaven and Earth’

THOMAS WYATT / FRANCIS TREGIAN

‘Songs’ XCVII

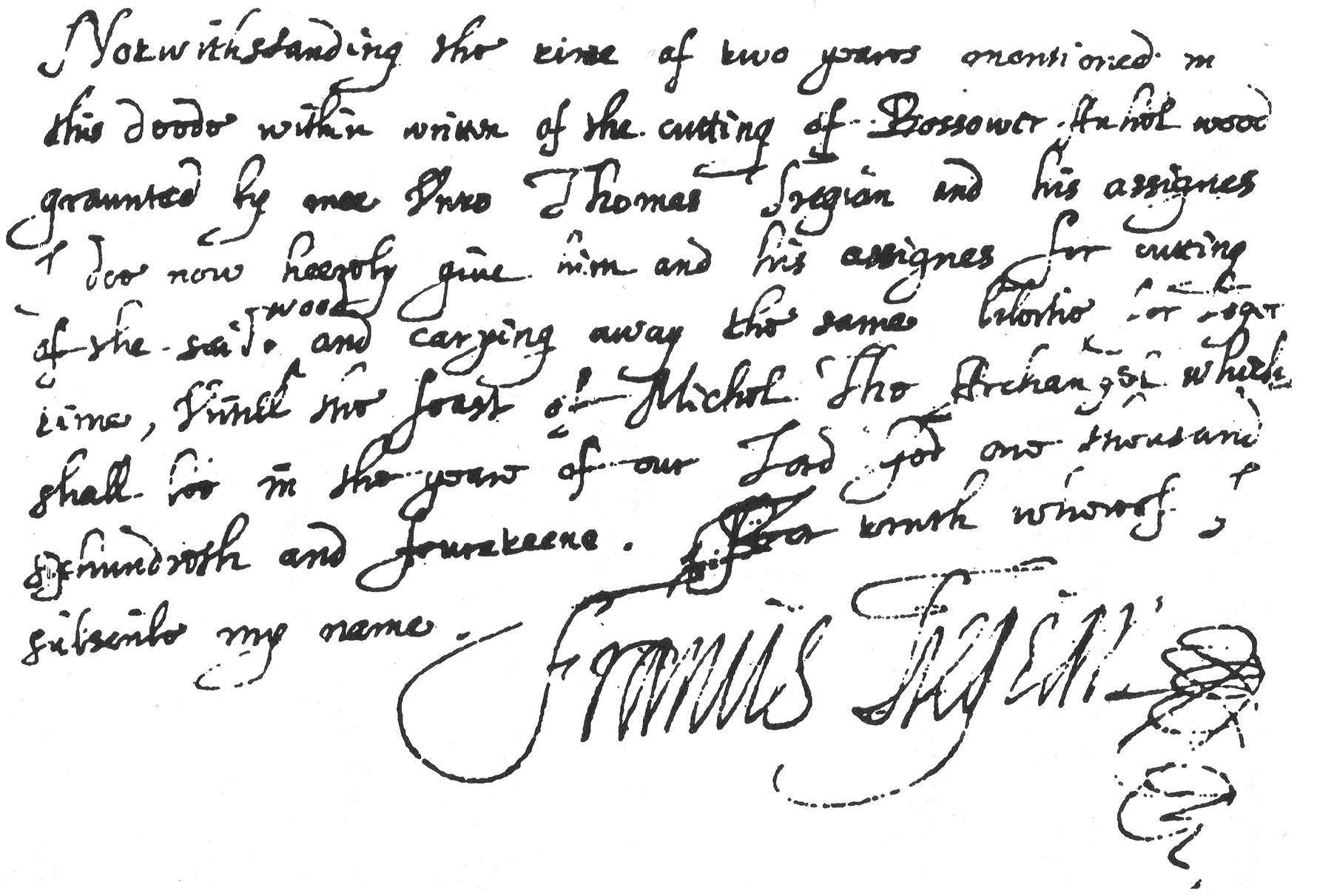

Document in the hand of Francis Tregian

(agreement of sale for a plot of forest, 18th March 1610)