CHAPTER V

THE CASE OF PRINNY’S DINNER

Freddy was a pretty busy pig for the next few weeks. Mrs. Winnick told all her friends about how quickly he had found Egbert, and her friends told other animals, and they all praised him very highly. At first Freddy tried to explain. He said that he really hadn’t done anything at all, and that he didn’t even know that the rabbit he had sent home was Egbert. But everyone said: “Oh, you just talk that way because you are so modest,” and they praised him more highly than ever.

And they brought him detective work to do. Most of them were simple cases, like Egbert’s, of young animals that had run away from home or got lost. But a number of them were quite important. There was, for instance, the strange case of Prinny’s dinner. Prinny was a little white woolly dog who lived with Miss Mary McMinnickle in a little house a mile or so down the road. Prinny was a nice dog, in spite of his name, of which he was very much ashamed. His whole name was Prince Charming, but Miss McMinnickle called him Prinny for short. Now Prinny’s dinner was always put out for him on the back porch in a big white bowl. Sometimes Prinny was there when it was put out, and then he ate it and everything was all right. But sometimes he would be away from home when Miss McMinnickle put it out, and he would come back an hour or two later and the bowl would be empty.

“The funny part of it is,” he said to Freddy, “that there isn’t ever a sign of any animal having been near it. I wish you’d see what you can do about it.”

So Freddy took the case. First he got some flour and sprinkled it around on the porch, but though the food was gone from the bowl when he and Prinny came back later, there were no footprints to be seen. Then he watched for two afternoons, hidden behind the back fence with his eye at a knot-hole. But on these days the dinner was not touched.

“Have you any idea who it is?” asked Prinny anxiously. The poor little dog was getting quite thin.

“H’m,” said Freddy; “yes. It’s narrowing down, it’s narrowing down. Give me another day or two and I think we’ll have him.”

Now, this time Freddy wasn’t just looking wise and pretending, for he really did have an idea. The next day, before the sun had come up, he went down to Miss McMinnickle’s. He took with him Eeny and Quik, two of the mice who lived in the barn, and they hid under the back porch. The mice were very proud that Freddy had asked them to help him, so they didn’t mind the long wait, and they all played “twenty questions” and other guessing games until finally, late in the afternoon, they heard Miss McMinnickle come out on the porch and set down the bowl containing Prinny’s dinner.

“Quiet now, boys,” said Freddy. “I told Prinny to stay up at the farm until after dark, so the thief will think that there’s no one here.”

For half an hour they waited. Then, without any warning, without any sound of cautious footsteps on the floor of the porch close over their heads, there was a rattling sound, as if someone were tapping the bowl with a stick. The mice looked at Freddy in alarm, but he winked reassuringly at them. “They’re there,” he said. “Wait here till I call you.” And he crawled quickly out from under the porch.

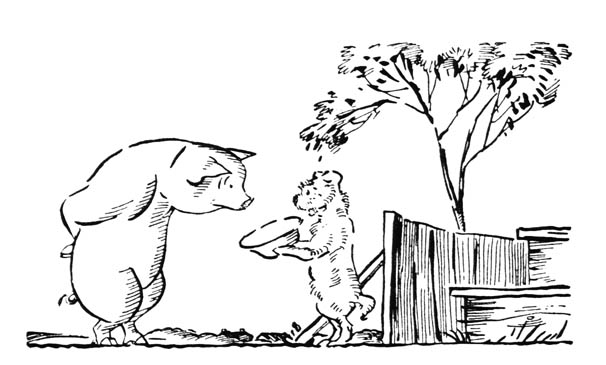

Three crows were perched on the edge of the big bowl, gobbling down Prinny’s dinner as fast as they could. At sight of Freddy they flew with a startled squawk up into the branches of a tree, from which they glared down at him angrily.

“Aha!” said the detective. “Caught you at it, didn’t I? Ferdy, I didn’t think it of you, stealing a poor little dog’s dinner! I knew it was some kind of bird when we didn’t find any footprints and when hiding behind the fence wasn’t any good. I suppose you saw me from the air, eh? But I thought it would be some of those thieving jays from the woods. I didn’t expect to find you here, Ferdy.”

Ferdinand, the oldest of the crows, who had been Freddy’s companion on the trip to the north pole the year before, merely grinned at his friend. “Aw, you can’t prove anything, pig,” he said. “Who’s going to believe you? It’s just your word against mine.”

“Is that so!” exclaimed Freddy. “Well, I’ve got witnesses, smarty. Come out, boys,” he called, and the two mice came out and sat on the edge of the porch.

Ferdinand looked a little worried at this. He was caught, and all the animals would soon know about it. Of course, they couldn’t do anything to him. But they would be angry at him, and it isn’t much fun living with people who don’t approve of your actions, even if they can’t punish you for them. In fact, it is often much pleasanter, when you have done something you shouldn’t, to be punished and get it over with. Ferdinand thought of this, and he also thought of his dignity. He had always been a very dignified crow, and it certainly wasn’t very dignified to be caught stealing a little dog’s dinner.

So he flew down beside the pig. “Oh, come, Freddy,” he said; “it was just a joke. Can’t we settle this out of court? We’ll promise not to do it again if you won’t say anything about it.”

“Well, that’s up to Prinny,” said the pig. “It doesn’t seem like a very good joke to him. But I’ll talk to him about it. You three crows had better not be here when he gets back, though.”

“All right,” said Ferdinand. “That’s fair enough. Do the best you can for us, Freddy. We’ll push off now.”

“Hey, wait a minute,” said one of the other crows. “How about these mice? How do we know they won’t talk?”

“Say, listen,” squeaked Eeny shrilly. “Just because we’re small, you think we haven’t got any sense, you big black useless noisy feather-headed bug-eaters, you!” His anger at the insult was so hot that he fairly danced about the porch on his hind legs. “Another one like that and I’ll climb that tree and gnaw your tail-feathers off!”

“Oh, he didn’t mean anything, Eeny,” said Ferdinand, edging a little away from the enraged mouse. “Sure, we know you won’t say anything.”

“Well, let him keep a civil tongue in his head, then,” grumbled Eeny. “Come on, Quik.” And he started off home without waiting for Freddy.

The pig overtook them, however, a minute later, and they climbed up on his back, for it was slow going for such small animals across the fields. “I must say, Freddy,” remarked Quik, “that I think you’re letting the crows off pretty easy.”

Freddy nodded. “Yes, that’s the trouble with this detective business. You see, there isn’t much of anything else to do. Of course with Ferdinand, I’m sure he’ll let Prinny alone now. He really did think it was more of a joke than anything else. But if he wanted to keep on stealing things, there isn’t anything I could do to stop him. We ought to have a jail, that’s what we ought to have.”

“You mean like the one in Centerboro?” asked Eeny.

“Yes. Then when we find any animal doing anything he shouldn’t, we could lock him up for a while.”

“You mean if a cat chased us, he could be locked up in the jail?” asked the mice. And when Freddy said yes, that was exactly what he did mean, they both agreed that a jail was certainly needed.

So that evening Freddy called a meeting of all the animals in the cow-barn, where the three cows, Mrs. Wiggins and Mrs. Wurzburger and Mrs. Wogus, lived. It was one of the finest cow-barns in the county, for when the animals had come back from Florida with a buggyful of money that they had found, Mr. Bean had been so grateful that he had fixed up all the stables and houses they lived in in the most modern style, with electric lights and hot and cold water and curtains at the windows, and steam heat in the winter-time. Even the henhouse had all these conveniences and such little extra comforts as electric nest-warmers, and little teeters and swings and slides for the younger chickens.

All the animals on the neighboring farms as well as at Mr. Bean’s had by this time heard about Freddy’s success as a detective, so the meeting was a large one. A lot of the woods animals, including Peter, the bear, came. There were even a few sheep, and if you know anything about sheep, you will realize how much interest the proposal for a jail had created, for there is nothing harder than to interest sheep in matters of public policy. Freddy found it unnecessary to make much of a speech, for nearly all of his audience agreed at once that the jail would fill, as Charles, the rooster, aptly expressed it, a long-felt want. Practically the only dissenting voice was that of Jinx. When Freddy threw the meeting open to discussion, Jinx jumped to his feet.

“I don’t see what we want a jail for,” he said. “We’ve always got along well enough without one before.”

“We got along without nice places to live in, too,” replied Freddy. “But it’s nice to have them.”

“Yes, but we aren’t going to live in the jail.”

“Some of us are,” said Freddy significantly.

“You mean animals like the rats, I suppose,” returned the cat. “Well, if you’re such a swell detective, why don’t you catch them and get Everett’s train back? If you aren’t any smarter at catching other animals that steal things than you have been about them, you won’t have anybody in your old jail. And anyway I don’t see any need for it. Let me get hold of those rats and you won’t need any jail to put ’em in.”

“I’ll catch ’em all right,” said Freddy. “Even Sherlock Holmes couldn’t do everything in a minute. These things take time. I guess I’ve settled quite a number of cases since I started being a detective, haven’t I?”

“Sure he has! Shut up, Jinx!” shouted the other animals, and Jinx had to sit down.

So the matter was voted upon, and it was decided by a vote of seventy-four to one that there should be a jail. But where? After a long discussion the meeting agreed that the two big box stalls in the barn would be a good place. Mr. Bean’s three horses lived in the barn, but they had stalls near the door, and the box stalls were never used.

“How do you feel about it, Hank?” asked Freddy.

Hank was the oldest of the horses, and he was never very sure of anything except that he liked oats better than anything in the world. “I don’t know,” he said slowly. “I guess it would be all right. Some animals would be all right, and then again, some wouldn’t. I wouldn’t want elephants or tigers. Or polar bears. Or giraffes. Or—”

“Or kangaroos or leopards or zebras,” said Freddy impatiently. “We know that. But there won’t be any animals of that kind.”

“Oh, then I guess it’ll be all right,” said Hank. “These prisoners, they’d be company for me, too. I’d like that.”

“That’s all settled, then,” said Freddy. “Hank can be jailer and look after the prisoners and see that they don’t escape. Then let’s see; we’ll need a judge, to say how long the prisoners shall stay in jail. Now, I suggest that a good animal for that position would be—”

“Excuse me!” crowed Charles, the rooster, excitedly. “I’d like to speak for a moment, Mr. Chairman.”

“All right,” said Freddy. “Mr. Charles has the floor. What is it, Charles?”

Charles flew up to the seat of the buggy, and all the animals crowded closer. The rooster was a fine speaker and he used words so beautifully that they all liked to hear him, although they didn’t always know what he was talking about. Neither did he, sometimes, but nobody cared, for, as with all good speakers, what he said wasn’t half so important as the noble way he said it.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” said Charles, “it is with a great sense of my own inadequacy that I venture to address this distinguished meeting. We have gathered here this evening to pay tribute to the genius—and I use the word ‘genius’ without fear of denial—of one of our number, a simple farm animal, who yet, by virtue of his great talents, his dogged determination, and his pleasing personality, has risen to a position of trust and responsibility never before occupied by any animal. I refer, ladies and gentlemen, to Freddy, the detective.” He paused for the cheers, then continued. “It has been said of Freddy that ‘he always gets his animal.’ But his career is too well known to all of you for me to dwell upon its successive stages.”—

“Yeah, I guess it is!” remarked Jinx sarcastically. “Why don’t he get those rats then?”

“And,” Charles continued without heeding the interruption, “who am I to come before you with suggestions concerning a subject about which he to whom I refer knows more than any living animal?”—

“I’ll tell you who you are!” shouted the cat, who was always thoroughly exasperated by Charles’s long-windedness. “You’re a silly rooster, and if Henrietta catches you up there making a speech again, she’ll make some suggestions you won’t like!”

“Shut up! Put him out!” shouted the animals, and Jinx subsided. But Charles was seen to shiver slightly. For Henrietta, his wife, didn’t approve of his public speaking, and she had been heard to threaten to pull out the handsome tail-feathers he was so proud of if she caught him at it again.

Presently, however, he recovered himself and went on, though somewhat hurriedly. “I do not wish to detain you unduly, so I will proceed to the matter of which I wish to speak: the matter of selecting a judge. Now, it is not easy to be a judge. When the prisoner is brought before the judge, he must hear all the facts in the case, and must first decide whether the prisoner is innocent or guilty. If guilty, he must then decide how long the prisoner ought to spend in jail. Now, this is not an easy task. Whoever becomes judge will have a great responsibility. He will, moreover, have very little time to himself. I feel sure that none of you animals will really want the position. But I have thought the matter over carefully, and I am willing to sacrifice myself for the public good. I wish to propose myself as judge.”

He paused, while some of the animals applauded and some grumbled.

“As to my qualifications for the position,” he went on, trying to look as modest as he could, which wasn’t very much, “it is hardly seemly for me to speak. You know me, my friends; whether or not I possess the wisdom, experience, and honesty necessary for this great task I leave it to you to judge. I have lived among you for many years; my record may perhaps speak for itself. I can only say that if you express your confidence in me by electing me to office, I shall do my utmost, I shall spare no labor, to be worthy of the confidence you thus express in me.” And he flew down from the buggy.

The meeting at once divided into two parties, one for Charles and one for Peter, the bear, who was Freddy’s candidate. Most of the animals who knew Charles well were for Peter, for though they were fond of Charles, they didn’t think much of his brains. “He talks too much, and he thinks too much about himself to make a good judge,” they said. But those who didn’t know him so well made the common mistake of thinking that because he spoke well, he knew a lot. They thought that Peter had brains too, but there was a serious drawback to Peter. From December to March he was always sound asleep in his cave in the woods, so that any cases that came up in the winter would have to wait over until spring. Some of the anti-Charles party said that didn’t matter; a good judge asleep was better than a bad judge awake. But the general feeling was that it wouldn’t be a good idea to elect a judge that slept nearly half the time.

A number of speeches were made, and the argument grew so bitter that most of the sheep went home, and two squirrels got to fighting in a corner and had to be separated before the voting could start. When the vote was counted, it was found that Charles had won.

The rooster wanted to make a speech of acceptance, and he flew back up on the buggy seat, but he had got no further than “My friends, I extend to one and all my heartiest thanks—” when Jinx, who had disappeared during the voting, stuck his head in the door.

“Hey, Charlie,” he called; “Henrietta wants you.”

Charles’s sentence ended in a strangled squawk, and he jumped down and hurried outside. But Henrietta was not there. Charles looked around for a moment; then, deciding that Jinx had played a trick on him, he turned to go in, when a voice above him called: “Hi, judge! Here’s a present for you!” And plop! plop! plop!—soft and squashy things hit the ground all around him. He dashed for the door, but he was a quarter of a second too late. An over-ripe tomato struck him fair on the back and flattened him to the ground, while peals of coarse laughter came from the roof.

He got up and shook himself. But it was no use. The handsome feathers he had cleaned and burnished so carefully for the meeting were damp and bedraggled. He could make no speech now; he couldn’t even go back into the cow-barn. A fine plight for a newly elected judge! But he knew whom he had to thank for it. Jinx had got those mischievous coons from the woods to play this childish trick on him. And he’d get even with them, see if he didn’t! They’d forgotten that he was a judge now. He’d put ’em in jail and keep ’em there, that’s what he’d do. And half-tearfully muttering threats, the new judge, after a mournful glance back at the barn, where honor and applause awaited him in vain, stumbled off across the barnyard toward the hen-coop.