CHAPTER XII

FREDDY SUMS UP

“I will show you, gentlemen of the jury,” said Freddy, “not only that Jinx is innocent of this crime, but that no crime has been committed. I will show you further that certain animals have been guilty of a conspiracy to deprive Jinx of his liberty and to cause him to be sentenced for this nonexistent crime.

“Now may I ask you to examine carefully the claws and feathers which are alleged to be those of a crow, killed and eaten by Jinx. You will remember that two chicken claws disappeared from Miss McMinnickle’s rubbish heap on the 6th, and that, by his own admission, Zeke was near that house at the same time. I suggest to you that those claws you have there are not crow’s claws at all, but the chicken’s claws, which were taken by Zeke or one of his relatives and placed in the barn.”

“But these claws are black,” said Peter.

“True,” said Freddy. “They have been colored black with ink. They were taken into the house by the rats who tipped over the ink-bottle on Miss McMinnickle’s desk while they were dyeing the claws. Here is a portion of the blotter taken from that desk. You will see on it the plain prints of rats’ feet.

“Furthermore, you have heard evidence to the effect that several rats were gathering feathers of various kinds in the woods on the 6th. Now please examine carefully the alleged crow’s feathers. I think you will find that they are of very different kinds. They are all black, true; but if you will smell of them and then smell of the ink-soaked blotter, you will find the two smells exactly the same. The smell, in fact, of ink. They have been dyed, just as the claws were dyed.”

Some confusion was caused by the efforts of the jury to smell of the feathers, which are very difficult things to smell of without getting your nose tickled. There was a tremendous outburst of sneezing in the jury-box, in the course of which the feathers were scattered all about the court-room, but when it was over and the feathers had been gathered together again, it was plain that the jury had accepted Freddy’s theory.

“I will ask you now,” went on the pig, “to remember several facts. There was no sign of a struggle in the barn, as there would have been if Jinx had actually caught a crow and eaten him there. The claws and feathers were laid out in a neat pile. Again, although there was only room in the three rat-holes for three rats to see what was going on in the loft, nine rats testified to having seen Jinx catch and eat the crow. Lastly, no crow is known to be missing, although, as all of you know, if one crow so much as loses a tail-feather, you will hear the crows cawing and shouting and complaining about it for weeks afterwards.

“Now, what happened was this, as you probably all see by this time. The rats wanted to get Jinx out of the way, so they could get a fresh supply of grain from the grain-box in the loft. They got the feathers and claws as I have shown you, dyed them black with ink, put them out on the floor, and then when Jinx came in, accused him of the crime. There is not a word of truth in their evidence. It is one of the most dastardly attempts to defeat the ends of justice which have ever come under my notice. I leave the case with you, confident that your verdict will free the prisoner.”

There was much shouting and cheering as Freddy concluded, and then Ferdinand rose to make his speech to the jury. He knew that he had a weak case, so he said very little about the facts. His attack was rather upon Freddy than upon the evidence that had been collected.

“A very clever theory our distinguished colleague and eminent detective has presented to us,” he said. “A little too clever, it seems to me. After all, it is the business of a detective to construct theories. But what we are concerned with here is the truth. We are plain animals; we like things plain and simple. Here is a dead bird, and beside it a cat. What is plainer than that? Do we need all this talk of ink and blue jays and chicken suppers to convince us of something that gives the lie to what is in front of our very noses? I think not. I think we all agree that two and two make four. I think we prefer such a statement as that to a long explanation why two and two should make six. With all due respect and admiration for the brilliance of the theory which Freddy has presented to us, I do not see how your verdict can be other than ‘Guilty.’”

There was some cheering at the end of Ferdinand’s speech, but it was more for the cleverness with which he had avoided the facts than because the audience agreed with him. And then Charles got up to speak. His speech was perhaps the best of the three. He referred to the grave responsibility which rested on the members of the jury, to the great care which they must exercise in deciding on the guilt or innocence of the prisoner. They must not be swayed by prejudice, he said, but must look at the facts as facts, must remember that—But it was a very long speech and, though beautifully worded, meant very little, so I will not give it in full. If you are interested in reading it, it will be possible to get a copy, for Freddy later wrote out an account of the trial on his typewriter, with all the speeches in full, which is kept with other documents in the Bean Archives, neatly labeled “The State vs. Jinx,” where I have seen it myself.

The jury whispered together for a few minutes while the audience waited breathlessly for the verdict, and Jinx sat quite still, looking rather worried, but with one eye on the dark space under the buggy where the rats were chattering together. Then Peter got up.

“Your Honor, our verdict is ready,” he said.

“What is it?” asked Charles.

“Not guilty!” said Peter.

At the words there was a burst of cheering that shook the barn and knocked two chipmunks off the beam where they had been sitting. Mr. Webb ran hastily up his thread and watched the rest of the proceedings from the roof. Jinx had jumped down from the buggy to receive the congratulations of his friends, who were crowding round him. But Freddy spoke to Charles, who crowed at the top of his lungs for order, and presently there was quiet.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” said the detective, “there is another matter before this court before it adjourns. I call for the arrest of Simon and his family on the charge of conspiracy, perjury, and just plain lying.”

The squeaking and chattering under the buggy became louder, and Ferdinand said: “You can’t do that, Freddy. We promised ’em they could go back to the barn in safety.”

“If you remember what I said,” replied the pig, “it was that unless they had committed some fresh crime before the trial was over, they might go back in safety. But they have committed a fresh crime. They didn’t tell the truth about Jinx, and that’s a crime, isn’t it?”

“H’m,” said Ferdinand, “I guess it is. Simon, come out here.”

Simon was no coward; he could fight when he had to. He came out now, grinning wickedly. He knew better than to argue, however. “You’re all against me,” he said. “Fat pig and stupid cow and silly sheep and stuffed-shirt rooster and all of you. Well, go ahead; sentence us to jail and see if we care. That’s all you can do. Come on out, Zeke, and the rest of you.”

The other rats were not so anxious to come out, but they were more afraid of Simon than of any of the other animals except the cat, so presently they crept out into the open space beside their leader.

“We’ll have this trial in order,” said Charles. “We’ve got a jury here, and you can pick somebody to defend you.”

“I’ll take care of my own case,” snarled Simon.

“All right. Jinx, you see that none of them try to get away.”

“Yeah!” said Jinx. “Watch me!” And he walked up and sat down beside Simon, who bared his teeth. But Jinx, who was a good-natured cat and couldn’t bear a grudge for very long, even when he had such good reason for it as he now had, merely winked at the rat. “Be yourself, Simon,” he said.

One by one the rats were questioned, their names and ages taken, and the question put to them whether they had any reason to give why they shouldn’t be sentenced. Acting under Simon’s instructions, they all said no. The smallest of the rats caused some amusement when he gave his name as Olfred.

“There isn’t any such name!” said Charles.

“There is too!” exclaimed the rat. “I’ve got it, haven’t I?”

“How do you spell it?” asked the rooster.

“O-l-f-r-e-d,” said the rat.

“It ought to be spelled with an A,” said Charles. “Alfred—that’s what it is.”

“It isn’t either. It’s Olfred,” insisted the rat.

“Nonsense!” exclaimed the judge sharply. “Don’t you suppose I know?”

“No, you don’t. Just because you never heard of it don’t mean anything. There’s lots of names you never heard of.”

“Is that so!” exclaimed Charles angrily. “I bet you can’t tell me one that I don’t know.”

“Yes I can,” said Olfred. “There’s Egwin and Ogbert and Wogmuth and Wigmund and Wagbert and—”

“You’re just making them up!” said Charles.

“Of course I am. But they’re names just the same.”

Charles gave up. “All right, all right, get on with the case.” And the questioning went on.

Simon was the last. Asked if there was any reason why he should not be sentenced, he said yes, there was, but that he had no objection to going to jail, so he would say nothing about it. “We’ve been living under the jail for some time,” he said. “We have no objection to moving up one story into the jail itself. It’s a pretty good place, from all I’ve heard, and you’ll have to feed us. I don’t see what you gain by sending us there, but that’s your affair.”

“There’s one thing we gain,” said Charles. “We have had a good deal of trouble with the jail, I’ll admit. Many animals have so good a time that they commit crimes just to be sent there. Some animals have even got in who haven’t committed crimes or been sentenced at all. But Freddy has suggested a remedy. All sentences, from now on, will be at hard labor. There’ll be no more playing games and carousing; the prisoners will work all day. The jail won’t be so popular from now on.”

The rats looked rather crestfallen at this. They whispered together for a minute; then suddenly, at a signal from Simon, they made a dash for the door.

They had been so reasonable during the questioning that even Jinx had been thrown off his guard. He made a pounce, missed Simon by the width of a whisker, then dove in among the legs of the audience after the fugitives.

“Let ’em go, Jinx,” Freddy shouted after him. “Keep ’em away from the barn, but let ’em go!”

Jinx gave a screech to show that he had heard, and scrabbled on among the legs of horses and sheep and goats and all the other animals who had jammed into the cow-barn to hear the trial. Even outside, the crowd was thick, but he made his way as quickly as he could to the edge of it nearest the barn. Not a rat was in sight. “Lost ’em, by gum!” muttered the cat, but he went on cautiously toward the barn, from which came the sound of hammering. Evidently Mr. Bean was repairing the floor that the robbers had torn up.

“They won’t dare go in that way,” he said to himself. “This hole under the door is the most likely one. I’ll watch that.”

He crept up toward it and then, to his surprise, saw that a piece of tin had been nailed across it. “Golly!” he thought. “If Mr. Bean has found out about the rats, I’ll be out of luck. He must have, too, if he’s found this hole and nailed it up.”

But there was one other hole on the other side, so he went round to watch there. He was pretty sure that the rats hadn’t reached it ahead of him. “If I can keep ’em out—” he thought, and then he saw that the second hole was nailed up too.

Inside the barn the prisoners, unaware of the hard work in store for them, were singing and laughing and carrying on.

“We raise our voices and shout,” they sang,

“And call the judge a good scout,

For he puts us in

And he keeps us in

And we’d rather be in than out.”

Jinx grinned; then, as the song finished, he heard someone talking. He stopped to listen. “… didn’t realize there were all them rat-holes in the old place,” Mr. Bean was saying. “When I saw ’em, I was kind of mad. ‘Jinx ain’t doin’ his duty,’ I says to myself, ‘to let them rats get a holt in here again.’ But there ain’t a rat in the place. I stomped all over the floor and took up a couple more boards and there wan’t a sign of ’em. So I nailed up the holes, case any should come wandering along looking for a home.”

“Oh, Jinx is a good cat,” said Mrs. Bean. “He wouldn’t let any rats get into the barn. Best mouser we ever had, Mr. B.”

“You always was fond of that cat, Mrs. B.,” replied her husband, “and I guess you been right. Takes a good cat to keep rats out of a barn with two big holes into it like I nailed up. Guess we might set him out an extra saucer of cream once in a while.”

“I’ll set out one for him this very night, Mr. B.,” said Mrs. Bean. “What do you suppose all that rumpus is down at the cow-barn this afternoon?”

“Oh, another of their meetin’s. I like to hear ’em shoutin’ and bellerin’ an’ havin’ a good time. I do hope they ain’t goin’ to take any more trips, though.”

“You must ’a’ read my mind, Mr. B.,” said his wife. “But they’re all taken up with this detective business now. That Freddy, he’s a caution. Brighter’n a new penny! But then, so’s Jinx.”

“So’s all of ’em, for that matter,” said Mr. Bean. “There ain’t a finer lot of animals in New York State, if I do say it myself.”

Jinx crept away. He was a very happy cat. All his difficulties had been solved at once. The jury had declared him innocent, and the rats had been shut out of the barn. Lucky the trial had been going on while Mr. Bean nailed up the holes, or he’d have nailed ’em inside, and then there would have been trouble. But everything was all right now.

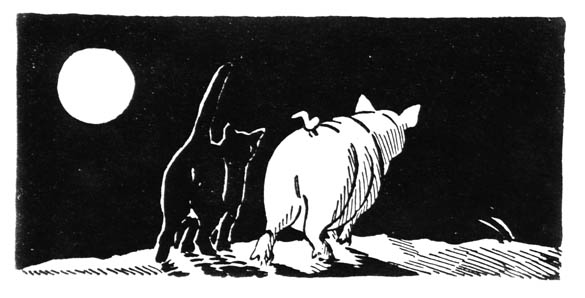

That evening he and Freddy and Mrs. Wiggins sat down by the duck-pond, watching the moon come up. The water rippled white in the moonlight—just the color, Jinx thought, of fresh cream.

“I’ve been working pretty hard the last few weeks,” said Freddy after they had discussed the day’s happenings. “I think I’m going to take a little vacation. Like to get off somewhere where it’s quiet and there’s nothing to do but loll on the grass and make up poetry.”

“I’m tired, too,” said Jinx. “All this rat business has got on my nerves. What do you say we take a little trip?”

“I think that’s a good idea,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “I can look after the detective business while you’re gone, Freddy.”

Freddy yawned. “Sure you can,” he said. “Gosh, I hate to think of going back to that office tomorrow morning and interviewing clients and figuring out cases. Funny how tired you get of even the things you like to do.”

“Like watching for rats,” said Jinx. “I know.”

“The open road,” said Freddy dreamily. “Remember that song I made up about it when we were going to Florida?”

“You bet I do!” said Jinx. “Let’s sing it, out here in the moonlight.”

“It’s a travelers’ song,” said the pig. “Ought to be sung when you’re on the open road; it’s sort of silly to be singing it when we’re sitting here at home.”

Jinx jumped to his feet. “Well, there’s your open road.” He pointed dramatically toward the gate, whose white posts glimmered in the moonlight.

Freddy stared at him for a moment; then he too jumped up. “You’re right,” he said. “What are we waiting for? Let’s go!” He turned to the cow. “Good luck, Mrs. W. Expect me back when you see me, and not before.”

Mrs. Wiggins watched them go through the gate and off down the road together. Long after they had disappeared, the sound of their singing floated back to her through the clear night air.

Freddy sings:

O, I am the King of Detectives,

And when I am out on the trail

All the animal criminals tremble,

And the criminal animals quail,

For they know that I’ll trace ’em and chase ’em and place ’em

Behind the strong bars of the jail.

Jinx sings:

O, I am the terror of rodents.

I can lick a whole army of rats

Like that thieving, deceiving old Simon

And his sly sneaking, high squeaking brats.

For I, when I meet ’em, defeat ’em and eat ’em—

I’m the boldest and bravest of cats.

Both sing:

In our chosen careers we’ll admit that

We haven’t much farther to climb,

But we’re weary of trailing and jailing,

Of juries, disguises and crime.

We want a vacation from sin and sensation—

We don’t want to work all the time.

And then they broke into a verse of the marching song that they had so often sung on the road to Florida.

Then it’s out of the gate and down the road

Without stopping to say goodbye,

For adventure waits over every hill,

Where the road runs up to the sky.

We’re off to play with the wind and the stars,

And we sing as we march away:

O, it’s all very well to love your work,

But you’ve got to have some play.

Mrs. Wiggins hummed the tune to herself for a while in a deep rumble that sounded like hundreds of bullfrogs tuning up. Then with a long sigh she got up and walked slowly back to her comfortable bed in the cow-barn.