When I was 17, I fell in love with mark-making and calligraphy. Little did I know that being left-handed was going to cause problems for myself and for some tutors and professionals in helping an eager student to reveal the complexities of the broad-edge pen. Some of them even voiced it loudly and clearly that it was impossible to teach left-handers because the basic training system was developed for right-handers and lefties should just stay away. All this frustration originated because of two issues:

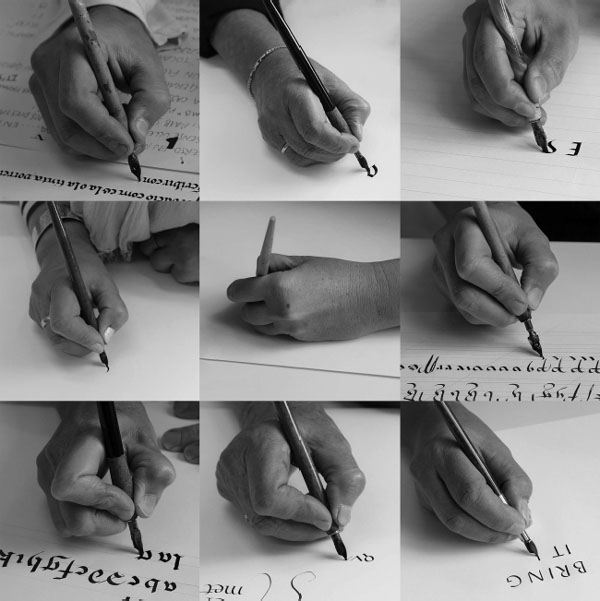

I must say I did feel for them. It just isn’t easy trying to get a group of people into the process of mark-making and letter-making: explaining the importance of posture, discovering new materials and focusing on the individual characteristics of these twenty-six letters of the alphabet can be overwhelming. There is so much to talk about and to show when students are starting out writing that one doesn’t want to spend time with just one student whose clumsiness is shown the minute he tries to write. The advantage of teaching right-handers is that in general, they will all be able to make a pretty good copy of the shape by demonstrating this once (Figure 5.1). Unfortunately, it usually doesn’t work for left-handers. Most teachers want their students to do well, and it just is not funny to see a left-hander struggle like mad to get the ink to flow, making a mess everywhere, and watch his frustration slowly move into anger. Both student and teacher could get quickly discouraged when at the same time most right-handers usually progress at a steady speed.

So, what is happening? Why is this not working?

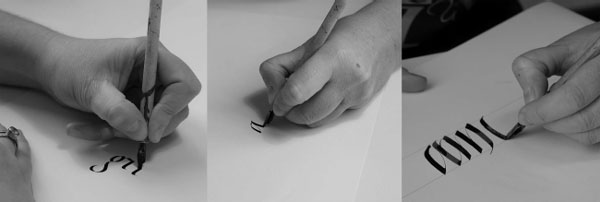

The whole idea is—no matter which tool we are using—is to get the medium (in this case, ink) to flow. Some tools—for example a pencil—show no resistance: no matter how you hold the pencil, it will make the mark you want; the graphite will come out without resisting the movement. However, a broad-edge nib will show a lot resistance: the scribe needs to pull the ink and not push it: this is the traditional writing tool to make calligraphic marks (see Figure 5.2).

Letterforms are made up of different individual strokes (called thicks and thins) and are being put together in one particular order, called the ductus. By following the arrows and numbers, most people can make a copy of the shape shown on the sample sheet, holding their pen and hand in a similar way.

It is therefore a useful tool and has helped many calligraphers deciphering the mysteries of the formal calligraphic form. Knowing the ductus also helps when using other tools, like a pointed brush or a ruling pen (see Figures 5.3, 5.4). But as with all systems and methodologies, we have to accept they don’t work for everyone. When a left-hander tries to write and has to push the pen, we see that the ink doesn’t flow well or the hairs of the flat brush show a lot of resistance. The hand is coming from the wrong side, making it difficult for the student to find the right angle allowing the letterforms to be made (see Figure 5.5).

And the problem doesn’t stop there. Why couldn’t we just define two teaching methodologies: one for right-handers and one for left-handers. From a rational point of view this would make sense since there are only two groups. But, here we come across another big issue: there are hardly any left-handers holding their hand, pen and paper the same way, which makes it extremely difficult to define a general approach.

Figure 5.6 A few ways left-handers tend to write.

Therefore, one could understand when teachers suggest lefties should just stay away from calligraphy altogether. It just is hard and time-consuming working with them and working out a way of writing which could work for them. If the teacher is not taking that time and has no interest in this issue, it is again very logical many left-handers never ever wanted to pick up a broad-edge nib again and turned away from calligraphy altogether. What a shame.

Although my first teacher gave up on me the minute he saw me write for the first time, it somehow never discouraged me. This ‘rejection’ created quite the opposite effect. I wondered if I could make this system, so useful for right-handers, work for me. For the next few years (and, to be honest, still every time I pick up a new writing tool) I needed time to find out how to pull the ink from the nib. So yes, it took me a lot longer to make any decent letterforms than my right-handed colleagues, but it also gave me insight in why we should be careful in overrating the power of the ductus. Learning calligraphy can be stigmatising and can limit one’s creativity if we’re not careful. Some teachers totally depend on the ductus system, therefore overlooking new ways of holding a writing tool which just could be the answer to left- and right-handers who are struggling with a certain script or technique. They impose a system which might not always work. And when it doesn’t, they give up.

In spending time discovering new teaching methods for myself based on trial and error, struggling with the limitations of my own body within the traditional way of calligraphic teaching methods, I realised I needed to break some of the dictatorial rules on what good lettering should look like. I was fed up with following these rules that made me smudge the paper all the time while my hand was going over the letterforms as I made them, the ink just didn’t flow correctly, tools all went the wrong way. Breaking the rules meant leaving the known and moving into the unknown. Of course, this brought uncertainty yet also freedom.

The regained freedom brought fresh air in my creative thinking and encouraged experiment and discovery. It separated relevant and irrelevant parameters established in the traditional teaching methods and distinguished main issues from side issues.

It made me realise that the heart of the matter is not how we get left-handers to use the ductus constructed for right-handers so that it makes life easier for the teacher, but how do we interpret the principles of the ductus and adapt them to each individual left-hander longing to make the shame shapes as their fellow right-handed students? And one could even go further: if we manage to apply these principles in a individual way, correcting and adjusting when and where necessary, we might also be able to help the minority of right-handers (yes, there are some) who are also struggling with the ductus and who are sometimes asked to leave a calligraphy group because the teachers thinks they just can’t write properly and will never do any decent work?

Figure 5.7 The position of the hands allows the left-hander not to smudge ink while writing.

And perhaps we could go really silly and rethink the whole ductus system all together and come up with new, more appropriate teaching techniques, taking away the power and the tyrannical impact the ductus methodology can have on people? Probably not yet, but thinking about it certainly could be useful.

Then a real challenge came when I was asked to teach a class of children for the first time. Still a student myself, I took this opportunity to try out exercises and see if I’d get everyone in that classroom to make traces or lines regardless if they were right- or left-handed. Also, being a left-handed teacher became now challenging for all the right-handed students. I had to make this work for them too. I managed to demonstrate all the letters while sitting in front of them and writing all the letters upside down. It was fascinating to see that right-handers were not confused by me sitting opposite and writing upside down. They hardly noticed my hand, but they focused on the letterform I made. They then picked up a pen and wrote. The ink flowed nicely, and the shapes were getting somewhere. If left-handers tried to do the same thing, they got nowhere. To them it was extremely important to watch my movement, where my body, hand and arm were when writing.

We could conclude that is seemed almost more important to them to focus on the way the teacher wrote to understand how the shapes could be made rather than the shapes themselves.

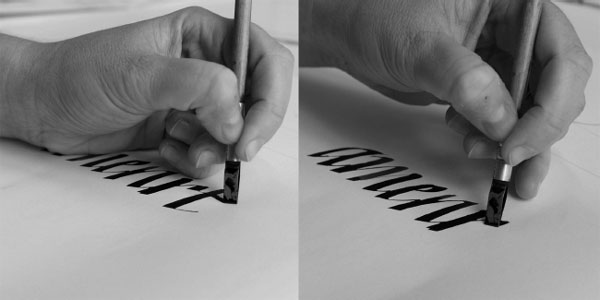

The thought that students don’t have to be ‘prisoners’ of the ductus but can have a deeper understanding of making lines by observing and memorising the movement and the shape of the counter-space between body and arm of the calligrapher demonstrating came about when I participated in a workshop on Roman caps with a flat brush earlier this year at our institute. Being totally convinced that it was impossible for a left-hander to use a flat brush, the teacher, Tom Kemp, a calligrapher based in London, told me how ridiculous that sounded. He showed me how the brush can be turned and twisted regardless of which hand held the brush and how irrelevant the whole right-handed–left-handed issue was anyway. I was thrilled to find out he was right about me being able to make the same shapes, but I was not convinced that following the ductus should make no difference to left- and right-handers. I tried it, but I just couldn’t get the same flow of line. Yes, the brush was doing the same movement as the right-handers, and somehow, it did not work. The lines were dull. The pulling and pushing of the brush had to do with it, but I needed to find a better answer than that.

While he demonstrated and I watched the movement, I focused no longer on the brush, but on the space he created between his axe of his body and his arm. I flip-mirrored the shape in my head and drew this new shape using my body axe and my left arm. It worked (see Figures 5.8 and 5.9).

Whereas my previous letterforms were lifeless and forced, I now had the freedom of movement and lively lines. The only difference is that the ink stayed at the top of the letter whereas right-handers have their ink at the bottom of the letters. Now, there is nothing new about left-handers writing from bottom to top instead of from top to bottom. What was new for me, however, was the insight in how to teach students when they get stuck and what they should be focusing on: not the letter, not the brush, but the space between the arm and the body axe (see Figure 5.10). I have tried out this new way of looking while creating letterforms. While left-handers will always need more time than the right-handers to reinterpret the right-handed ductus, we notice that, when the translation has been done and understood, the output is quite extraordinary. Needless to say that this process of understanding, exercising and applying takes time. Lots of it.

Then let it go. And start again. And again.

If you think about it: there were a few good reasons to set up school focusing on letter- and mark-making: First, almost all long-term courses had stopped, and calligraphy and lettering fell into some hobby circuit, where they tell you anyone can become a calligrapher in eight sessions. This just isn’t true, and it has been a disaster for our profession having all these so-called lettering people around. But that’s another discussion altogether. Serious students need time to become professionals. By introducing a long-term educational programme, we give them time to understand, experience and experiment, fail and try again. Also, I think the traditional way of working stopped many people from going to a calligraphy class, especially a younger generation. We decided to leave group teaching behind and focus on an individual based learning programme, paying attention to individual needs and shortcomings, therefore creating a more efficient learning environment.

The reason for this approach is simple: to be honest, there is no real mystery in all this. When people ask me how I teach, there is only one answer: come to the school, sit down and watch. Or even better, sign up for the course, and I will show you and share my experience with you. Because I draw and I write while I talk about it. I observe students, I look for their strong and weak points. We look at what others have done. We compare. And then we practice. Over and over again. Mark-making cannot be learnt from reading a book about it; you have to do it. It is as simple as that. And you need someone who knows about trace-making who can watch over you and correct you when you are not getting the result you want. You cannot learn how to become a triathlete from reading about it. You need to train. Many hours. Many years. You need to know your body, your physical and mental strengths and weaknesses, you need to gain knowledge on the materials you use, thus improving your technical skills, and you need to know the environment in which you will compete and who the other competitors are. You need to know what the tendencies are, what your talent is. And you need a good trainer.

We do exactly the same thing at our school. We train people on a one-to-one basis. We’re breathing down their necks when necessary; we push them to their limits when needed, and we give then a break before they collapse. Some of them make it; some of them don’t. This can’t be described in an article or a book because reading about it just isn’t enough; it involves not just the brain but also the whole body. The body doesn’t understand books but absorbs information in a different way: when you twist someone’s hand just a little, the body feels it: the muscle memory has been activated, and the student suddenly understands what has to be done, much better than if you were to explain this in a rational, verbal way. I observe the students for a long time, look at their posture, how they write and walk. Writing about this like I do now doesn’t make a lot of sense, I need to sit in front or next to the student, hold his or her hand, straighten or change the angle of his or her back. And sometimes it takes a long time before we get it right. Sometimes people are so far removed from their body that I encourage them to do yoga or Tai Chi; to go running, stretch, jump up and down; to go roller-skating; or just sit quietly till they connect again with their body and realise that they are a whole being and not just a brain.

For a line to be made the way you want it to be made, you need a lot of parameters coming together at the same time. You need a brain to understand how lines are made, eyes that can see what the hand is doing and a hand who makes the mark. It is not just making or just thinking. It is a combination of thinking and making, doing and not doing, spontaneity and rationality, structure and chaos. And the problem is that the order of learning can be switched around depending on the person you’re working with. So it is therefore impossible to write down a series of exercises in a particular order. If you don’t have the right trainer who understands, knows and can demonstrate the exercises, you won’t have a good result. But a mentor who understands will know that when the hands don’t understand, the brain or the eyes usually do, when the eyes fail to see, the brain will know or the body will feel, and when the brain just fries up, the eyes and the body usually connect and do the work. Trusting that one of these three will have the solution is very reassuring and should give the teacher or mentor confidence even when dealing with difficult students.

This leaves us with one more thing: When we are able to make marks and traces, what do we do with them and where do we place them? And if we place them differently, does this affect our perception of the image?

To understand visual language we use the same principle as in any other language, paying attention to its two main actors: first of all, its vocabulary (which is defined by the graphic elements, in this case, the lines) and then its grammar (which is being defined by its composition or layout).

Students have discovered how to make lines by spending time on repeating exercises, discovering tools and making different movements, allowing for different kinds of lines to appear. But these lines are useless unless we place them in an environment, be it written on a piece of paper, carved in stone or hanging in a building. We also need to understand the difference between looking at just one line, multiple lines and when or if they interact with one another. If we think this process of adding lines through, it is easy to see how complex this graphic environment can become.

Students are now faced with a whole new dimension: whereas before we only focused one making lines, we now need to decide if one line will touch the other or not and what will happen to the total image when changes are made. Will the created image still be ‘read’ the way I envisaged or are my lines being interpreted in a different way by the viewer? When we start asking ourselves these questions, we have reached the heart of visual communication, which is called layout or composition. We already react differently to different lines, but when they come together we enter a new dimension. The space in, between and around the lines become important and start playing a role, and when we involve even more surfaces and more lines, we need to be aware we again create a different story, a different context, a different atmosphere. The image we create is being read differently. We can compare this using a simple phrase, using the same words, but changing the order. If I say, “My garden is green”, or “Green is my garden,” or “Is my garden green?” I am using the same words, but it will be interpreted differently by the receiver. When I say “Garden green my is”, I am still using the same words, but now we don’t recognise the structure anymore. The message might not be understood. The same things can happen in visual language.

For most students, layout is a tough part of their education. They think that content—the meaning of the words—will solve any layout problem. This is sadly not true. Understanding the basic layout rules and being able to apply them are, to my personal belief, crucial knowledge any designer should own. Again, on this matter, you will find very few good books or articles. The reason is simple: reading about it just isn’t enough. We need to physically shift around the shapes for students to explain the importance of the counter shapes, to realise how to create tension or not in a composition.

If we—as designers—are interested in visualising meaning of content it is not enough to make beautiful or powerful lines, we also need to accept that layout is at the heart of visual communication. Finding the appropriate harmony between lines and layout will allow us to communicate properly. Once students have understood the basics of visual language and once the hands can do, the eyes can see and the head can think in a more connected way, shifting with more ease from thinking to making and the other way around, any student can start developing his or her own design skills and can move on to more complex assignments. My role, as a teacher, as a mentor, changes, becomes less relevant and slowly, the student will leave the nest and fly, confident and skilled. As a teacher, this is, of course, what it is all about.

I have been struggling writing this chapter. First I totally forgot about it, then Christian Mosbæk Johannessen reminded me kindly to send in my contribution on how I teach at the European Lettering School. I tried to explain it was just impossible because of so many reasons mentioned earlier, but he gently wouldn’t have it. Then Karine Bouchy tried to convince me as well. And my colleague Brody Neuenschwander pushed me in the nicest way possible to try putting my thoughts down on anyway. Of course, I gave in, and I am glad I did.

What bothered me the most was that I didn’t know why I resisted writing this chapter? I never experienced such a wall, a non-desire to write. Suddenly, I realised why. I had to write about how I teach. And I simply can’t because I have nothing fancy to say about it. My teaching is based on what life has taught me. I never understood why I studied for so long, struggling like mad day in day out. It just didn’t make sense. Now that I draw inspiration from my own experience and pass on my knowledge and skills to a new generation of lettering designers, it all comes together and makes the effort so worthwhile.

Being part of the Symposium “Making Traces” in Odense in 2014 has been a real eye-opener to me. I have been impressed listening to everyone talking about lines, traces, flow, movement and so much more. I was astonished, however, to discover that many of the speakers hardly had any physical experience of how to actually make traces. Questions were asked which seem so obvious to a practitioner. Brody Neuenschwander’s workshop seemed to be an eye-opener for many participants. I realised there was a different world interested in the same thing but approaching it from a different angle. And how silly it was this had never crossed my mind? Thinking about it, I still find it easier to understand that people make lines without this theoretical approach than people talking about it without having made a trace. But, as a calligrapher and teacher, my main question remains: What does all this analyzing really mean for the practitioner, the person who at the end of the day needs to produce this required line, the line that will be criticised or admired? And does this theoretic approach help a teacher in training a new generation of designers in any way? Coming back from Denmark, I realised that yes, having scholars out there putting words to what we do is valuable because it can help us explain principles to particularly critical students about lines and trace-making in a different way. But I do hope the exchange will go both ways. Just talking about it is certainly not enough to understand the complexities of trace-making. Making the line involves our so much more than a rational approach: hands, head, eyes and body have to work together; the whole physical activity makes it happen. And only by failing and starting again, we will gain a deeper understanding of the essence of the line.

All pictures were taken by Ingrid Depoover. Thanks to all students at ELI 16–17 for lending their hands to demonstrate different ways of writing.