I am writing this chapter in Microsoft Word. Before I started writing, I did not spend any time wondering which programme I was going to use but immediately clicked the Word icon and chose the “empty document” template. Even before I started writing, my Word document was, however, never an empty document but filled with a preset configuration of semiotic and aesthetic norms. Word 2010 for Windows for instance prescribes that the body text should be in black Calibri, font size 11, with headings in blue Cambria. That is, Word comes with a certain look, or style. This style has become a highly regular sight in contemporary culture as we encounter Word documents in a broad variety of situations in our everyday and professional lives. Word documents are exchanged in meetings and seminars, printed documents are put on walls, boards and tables, and we see the interface of Word on computer screens around us everywhere—in offices, cafes, and trains, and usually without even noticing it. The style of Word has thus become an important, although often little acknowledged, display in society.

Microsoft Word does not only compose the well-known empty document but offers a broad variety of other templates as well, for instance, to-do lists, memorandums, flyers and business cards. Word templates are not merely tools for text composition but also serve to pre-decide the visual style of documents—Microsoft has decided in advance how our written verbiage and other graphical expression should appear visually, and how all elements are to be integrated into an overall layout. Consequently, Word templates possess powerful normative and standardising functions.

The standardising function of templates impacts on how individuals can design the visual displays of their Word-based texts, and, consequently, on how people can express identity in Word. One particularly important category of templates for identity expression is the business card template. According to the Oxford Dictionary a business card is “a small card printed with one’s name, professional occupation, company position, business address, and other contact information.” By selecting, filling out and adjusting a Word-based business card template, the semiotic elements on the card become interpretable to others as signifiers of a more or less unique identity.

Identity categories and expressions are not naturally given, but created by language and other semiotic means within a social and cultural context. In Word´s business cards templates, all available resources for identity construction have been deliberately selected and designed by Microsoft. Microsoft is today one of the world’s most powerful financial, social and semiotic institutions whose norms are enforced in all social practices in which the program is used. Identity also relates to power, and as Bouvier (2012: 44) writes about equally powerful Facebook, “[p]owerful institutions will seek to naturalise those [identity categories] that support their own interests. […] Whose interest, we must always ask, do these identity categories serve?” This is particularly important in the case of Word, as the program´s cultural dominance for the past 25 years has rendered the program so mundane and common sense that it today tends to pass below the scholarly radars for what constitutes an interesting or worthy object of study.

In this chapter I use the design of a business card as an example for showing and critiquing how Word contributes to regulating and standardising styles and identities. The discussion is theoretically informed by multimodal social semiotics and its perspectives on semiotic technology, normativity, identity and style. The chapter does not aim at finding out how ‘effective’ it is to design a business card with Word (it obviously is not the best tool) but to contribute to an increased critical awareness of the normative powers of Microsoft Word and of the way social values are built into ubiquitous software and templates, shaping and constraining possibilities for the semiotic expressions of identity.

Microsoft Word is an applications software, or end-user program, often referred to as a word processor. Application software, including Word, is usually discussed in terms of functionality; how well a particular program is suited for performing certain tasks, or how ‘user-friendly’ it is. From this perspective, software is seen as a tool that is more or less apt for conducting some practical task. This discourse of functionality is evident in a broad variety of genres, such as many academic papers in Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), review articles on tech websites and tip columns in magazines. Another prominent approach is to conceive of software mainly as technology, as a matter of processing of algorithms and codes. Consequently, software becomes located beyond the scope, or at least comfort zone, of most of the humanities and social sciences. Even though software obviously is a matter of both functionality and technology, this is not all software is, and, importantly, these approaches do not suffice to shine light on the socially regulated materiality of Microsoft Word expressions.

In the field of software studies (Manovich, 2001, 2013; Fuller, 2008), researchers treat software not as a tool but as an object of study in its own right. Scholars aim at showing and critiquing how software penetrates people’s everyday lives and all parts of society and at culturally, historically and aesthetically discussing how software is experienced (Fuller, 2008, 1), in line with the aims of this chapter. Software study approaches are, however, limited in terms of digital text, or interface, analysis; the core research interests are not aimed at investigating how specific software contributes to enabling and shaping actual instances of semiosis. Theo van Leeuwen and Emilia Djonov (2013: 1) also argue that software studies lacks a unifying social theory of meaning-making that can explain how different semiotic resources interact in relation to the sociocultural contexts in which they are used.

However, this is the approach taken in the emerging subfield of social semiotics called semiotic technology, the perspective which this chapter adopts (Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2011; 2012; 2013a; 2013b; van Leeuwen, Djonov and O´Halloran, 2013; Zhao, Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2014; O´Halloran, 2009; Kvåle, 2016; Poulsen, 2015). Social semioticians investigate semiotic resources in culture, such as language, images, colours and graphics; study how these resources are used and socially regulated in specific historical, cultural and institutional contexts (van Leeuwen, 2005); and understand communication and representation as multimodal by attending to all expression forms people use (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001, 1996/2006; Kress, 2010; Jewitt, 2009). These basic assumptions are in a semiotic technology perspective extended to technologies, in particular, digital technologies.

In a social semiotic technology perspective, software is viewed as a semiotic resource: “a semiotic resource that has material form, that incorporates selections from different semiotic modes (e.g. layout, texture, colour, sound) and media (e.g. visual, aural, print, electronic), and that is deployed for making meaning alongside other types of semiotic resources” (Zhao, Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2014: 355). When software is viewed as a semiotic resource, it can be investigated and critiqued in terms of the technological and sociocultural affordances it offers. The concept of affordances, originally coined by perception psychologist James J. Gibson (1986 [1979]), is in social semiotics used for referring to what it is possible to do, easily and readily, with a semiotic mode, given its materiality and its cultural and social history (Jewitt and Kress, 2003: 14f.). The notion of semiotic technology thus signals an interest in technology as integral to meaning making and graphical expression, and treats software as a social and semiotic matter, not only a matter of technology and functionality. In accordance with this view, Microsoft Word is in this chapter viewed, not simply as a tool, but as a semiotic artefact loaded with historically developed socially and ideologically regulated meaning potentials which influence how people express styles and identities and how people can express styles and identities.

The business card example of this chapter is only one of many templates Word offers. However, working with almost any application software today involves working with digital templates. Professor in rhetoric and technology Kristin Arola (2010) claims that today,

[…] users post within preformatted templates designed by the site’s creators. In the late 1990s, creating a web page through either hand coding or a WYSIWYG program necessarily included choices of how and if to incorporate graphics, colors, fonts, sounds, and hyperlinks. Today, our students still choose photographs, words, sounds, and hyperlinks (clearly all rhetorical choices), but they choose colors, fonts, and shapes less and less. Instead, the platform, or more specifically the design template, is chosen for them.

(Arola, 2010: 6)

The cultural rise of templates means that digital expressions are becoming less and less personally designed but, rather, are inserted or posted into a more or less ready-made semiotic environment, for instance, a Microsoft Word’s business card template.

The contemporary influence of digital templates renders them culturally salient sets of affordances for multimodality. However, templates have yet not been awarded much analytical or critical attention in multimodality studies. One important exception is PowerPoint templates, which, in particular, have been addressed by Djonov and van Leeuwen (2013a), who describe templates as being “based on an understanding of the key generic components of certain document types; it specifies where and how they should be distributed” (Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2013a: 13). In addition to the compositional aspects highlighted in their description, templates may also provide users with verbal or visual content or suggestions thereof, suggested sets of social roles and identities to take up on, and particular aesthetics in the visual displays. A digital template, in the case of this chapter a Word business card template, is thus understood as a software-based site in which the social is unfolded and enforced through a pre-designed semiotic environment for making specific document types and into which users can insert semiotic resources in accordance with the software´s social and semiotic regulation

Business cards have to do with expressing identity; with communicating who you want to be seen as by receivers of the card. In social semiotics, as well as in discourse analysis in general, the expression of identity has to do with style, with the manners that somebody presents themselves in (van Leeuwen, 2005; Machin and van Leeuwen, 2005; Fairclough, 2003). Machin and van Leeuwen (2005; van Leeuwen, 2005) distinguish three kinds of ideas about styles: individual style, social style and lifestyle. Individual style has to do with individuality, with the way feelings, attitudes and other expressive dimensions are enacted “in the interstices of social regulation” (van Leeuwen, 2005: 141), evident in for instance the uniqueness of handwriting. Social style has to do with relatively stable social identity categories such as gender, age, roles, class, and social ‘markers’ connected to these. Lifestyle, which today is the most influential source for identity, combines the individual and social by being based on shared consumer taste, leisure activities and attitudes, and their signification rests on the connotations of the display. Styles and identities are thus made available for interpretation through how the connotations of the appearances associate with and dissociate from more or less easily recognisable communities of tastes, interests and ideologies.

Subsequently, business card styles and identities can be approached by analysing the connotations of the appearances of the card, that is, what cultural associations to places, times, groups, ideologies, interests and so on the elements on the card refer to. For instance, if a card includes visual elements like books, chalk and blackboard, these elements are interpretable as connoting the social identity of a teacher and/or a lifestyle connected to school and educational activities.

Styles and identities are socially regulated in more or less flexible and more or less explicit ways. In the era of print, some visual displays were strictly regulated by explicit norms. The layout of formal letters, for instance, was dictated by detailed style manuals and by overt instruction in schools. In the era of the computer, software and digital document templates have taken over as the most influential social enforcers of norms. Djonov and van Leeuwen (2013b: 235) claim that “new writing is more tacitly regulated, not through style manuals and explicit teaching, but by rules built into semiotic technologies such as office software”. The normative powers of software also concern templates: “Templates embody the value of prescriptivism as they offer everyday users professional layout design solutions and presents these as rules to be followed” (Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2013a: 15). Because of Microsoft Word’s worldwide presence, the norms of this particular software are of critical importance as they are overtly and covertly enforced on a global scale.

Templates are pre-decided semiotic environments shaped by social interests, and a given business card may therefore not only reflect the identity of the cardholder, but also the values and ideas it has been shaped by. A business card template thus may resemble image bank photography in terms of presenting an “ideologically pre-structured world” (Machin, 2004: 334f.), offering identity clichés and generic displays that serve the interests and needs of powerful corporations. A discussion of the normativity of Word and Word templates is thus relevant not only for understanding the socially shaped materiality of writing in mundane everyday tasks but also for increased critical awareness on the roles of ubiquitous software in society.

In multimodality studies. Microsoft Word has previously been addressed by the author (Kvåle, 2016) in a study which showed how the program imports ideologies and styles from office management into higher education through the styles and discourses inherent in SmartArt graphics. The study showed that hierarchical SmartArt templates are historically developed decorated organisational charts and how verbo-visual hierarchical representations of knowledge in higher education, which traditionally has preferred an abstract minimalist style, become dressed up in accordance with the embellished SmartArt style. It also argued that Microsoft Word throughout its history has understood conceptual representation as the production of alphanumerical letterforms, while visual resources (WordArt, ClipArt), typography and colours are presented as ways of ornamentally spicing up the written text.

Within software studies, Matthew Fuller (2003) has critically and wittily addressed Word and the program’s social and aesthetic ideas. He observes how Word has become increasingly overloaded with functions and features that hardly anybody uses, and he also addresses templates. “The templates”, he writes, “acknowledge that forgery is the basic form of documents produced in the modern office”, exemplified with the ‘419 Fraud’ template for so-called Nigeria letters, named after the Nigerian statute that abandons it. He also argues that templates make writing itself peripheral to processing: Word’s idea of word processing involves a mechanical and action-aimed kind of work in which every possible document is made ready for production by the mere selection of the right template.

Other software scholars, Olav Bertelsen and Søren Pold (2004), have critically discussed the aesthetics of the Word interface as part of an alternative to the functionalist approach usually taken within HCI. They argue that the program promotes a business kind of writing modelled on office writing practices (see also Pold, 2008), and that it lacks support for creative and non-office writing. They see Word as belonging to ‘a tool genre’ in which the user controls the content while Word serves as a kind of neutral tool for helping users with the form.

The seminal work Software Studies—A Lexicon (Fuller, 2008) covers a broad array of topics, but digital templates are not amongst the entries. In an entry on preferences, Pold, however, discusses normativity of software in terms of the asymmetrical relation between user and producer:

[…] the interface is structured around principles set up by the sender(s) […] Preferences regulate the contract between the producers, the machine and its software environment, and what I as a user prefer, thus my preferences are not purely mine, but highly negotiated in this software hierarchy.

(Pold, 2008: 219)

Besides the studies referred to here, there are surprisingly few studies on the semiotics, rhetorics and aesthetics of Word. In comparison, there is today a considerably body of research on the ubiquitous Microsoft program of PowerPoint. This includes social semiotic technology studies (Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2011; 2012; 2013a; 2013b; van Leeuwen, Djonov and O´Halloran, 2013; Zhao, Djonov and van Leeuwen, 2014) as well as rhetorical studies (cf. Tufte, 2003; Kjeldsen, 2006), cognitive studies (cf. Meyer and Moreno, 2003) and educational approaches (cf. Adams, 2006). The amount of previous research on Microsoft Word thus stands in sharp contrast to the amount of previous research on PowerPoint and, even more important, in sharp contrast to Word´s pervasive role in society. Hence, a critical discussion of Word and Word templates presents itself as all the more timely.

The following discussion of Word’s stylistic normativity will depart from one example of business card design, taken from a small exploratory study where four participants were asked to design a business card for a fictive persona. The participants were not professional designers but laypersons in the age range of 35 to 45 who have experience with Word from everyday and professional practices. They started out by creating an identity for the persona the card belonged to (name, age, profession, interests, etc.) and then designed a card for this persona using the available business card templates in Norwegian Word for Windows 2010 on a desktop PC. Their designs were documented through screen recordings, and the researcher/chapter author sat next to them and took notes and talked with them about their design choices.

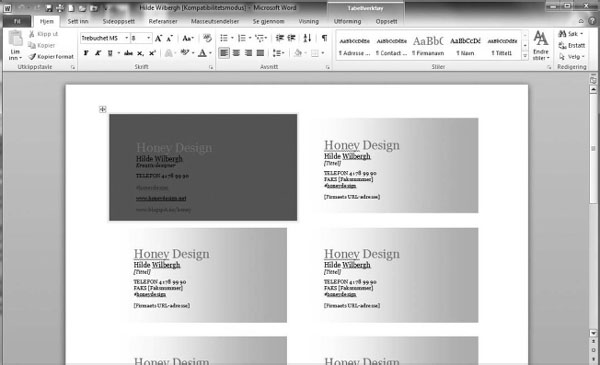

The example to be used as reference point is a card made for a fictive 39-year-old female creative designer called ‘Hilde Wilbergh’ who has a company called Honey Design. The informant-designer defined her as somebody who is very interested in design, interior blogs, magazines, vintage stores and travelling. Figure 8.1 shows a screenshot of Hilde’s business card. The upper-left card is the one the informant worked with, while the other cards show how the informant’s semiotic work is transferred to the rest of the cards in the template.

The business card displays style and identity through the connotations of the appearance of the card. Hilde’s card has a flat deep-purple background (viz. modulated in the template cards), headed in golden-brown Georgia, and a list of contact information in Georgia black. Gold could be said to connote ‘wealth’ or ‘glamour’, and purple might refer to ‘colourfulness’ or ‘femininity’, but none of the graphical resources on the card use provenance or metaphors to refer to very specific lifestyle communities. The card has few hints to specific social groups or values, but deploys rather unmarked expression forms. Consequently, I argue that the appearance of Hilde’s conveys a generic style.

My discussion investigates and critiques how this generic style is multimodally designed and socially regulated. I do so by discussing the style of the card in four steps, starting with the design of the card and gradually ‘zooming out’ to style norms in the software: (1) the style of the card, (2) the styles of the available business card templates, (3) the style in Word’s interface and (4) style norms in Microsoft Word.

First, I discuss the generic style of Hilde’s card by studying the informant’s negotiations with the selected Word template.

The informant started by scanning through all five available templates in the template collection (cf. Step 2) before making her choice: “I think it has to be this one”. She then designed the alphanumerical elements by compliantly typing the requested information of the template. One piece of information was however opposed: “Fax? Nobody has fax! Can I remove that? Hilde doesn’t have fax”. She also requested the possibility to include graphic expressions that were not easily available: “I would like to have the logo here, to the right”, to include pictures, “for example a cool vase”, and more colours: “If you are the kind of person who would like more colour, can’t you have that? Cause since I’m into design, I need colours”. She added the hashtag “#honeydesign” and a blog address before playing around with font colours. After clicking several tabs she discovered how she could change the background of the card and tried out several colours before settling for the deep purple (cf. the upper-left card in Figure 8.1).

Her design process clearly shows the importance of templates for making and styling multimodal expressions in Word, in particular, the templates’ affordances for written language, background and pictorial elements. First, an individual style of the card is afforded through the templatised verbal resources. Certain pieces of verbal information—firm name, personal name, phone number—are placed in brackets in the template and thereby conveyed to the user as editable text. Written language is the only resource that is presented as easily editable in this way, and written language is thereby presented as the singular most important resource for identity expression.

However, the cards in Figure 8.1 show that the verbal expression of an individual style is in fact also constrained by the template, as only the editable text in the template is automatically transferred to the other cards. Her additions (hashtag, URL) are not automatically transferred, and neither are her subtractions (fax information). Thus, the affordances of the template not only guide the user to construct an individual identity first and foremost through written language but also narrows it further down to those pieces of written information that are preset as standard in the template.

Second, stylistic resources for identity expression are offered through the visual display of the card, significantly the background. The background is not presented as editable, but it can be altered, and as shown, the informant did change the background colour in order to provide a visual display in line with Hilde’s identity. However, her individual background design (flat purple) was not transferred to the other cards but overruled by the standardised background of the template (modulated light purple). The presentation of the self was thereby forced back into the predefined visual setting—the user’s preferred visual display was overridden by the preferences of the template.

A third set of important affordances for the visual construction of identity in a business card is pictorial elements. The informant requested the presence of such elements in order to connote the lifestyle identity of the card owner (“a cool vase”, “a logo”). The selected template does however not include any such element by default, and it therefore does not support any convenient adding of such elements. As shown, the user did not use any visual elements that served to identify or connote a particular personal or lifestyle identity—even though she wanted to. The individual style of the card was thus constrained also by the absence of choice of pictorial elements in the templates.

Summing up, the generic style of Hilde’s business card has been shown to be shaped by asymmetrical negotiations between the user and the software-based template, as the templatised standard design continually prevailed over the design efforts of the user. The verbo-visual expressions on Hilde’s card are thus principally not to be understood as the results of the informant’s creative and reflexive design choices but, rather, as being present on her card because they happened to be the semiotic resources that were set as standard in the template. The informant´s business card design thus showed how the template functions as a normative rule that the individual is forced into complying with.

Second, I take a closer look at the styles and identities that are made available to users in Word’s business card template collection, shown in Figure 8.2.

The version of Word used in the example comprises five different business card templates labeled (1) “General business card”, (2) ”Card for technology company”, (3) ”Business card for small company”, (4) ”General business card” and 5)”Appointment card.” Microsoft Word in Norwegian glosses the genre “Visit card” (”visittkort”), but all the cards are connected to a business context in line with the English term. The available identities for Hilde are thus narrowed down to roles and positions in social practices of business.

The first of the two general business cards has a green vertical line to the left, an abstract image of a black globe in the lower-left centre, an editable heading with “[Company Name]” in green fonts to the top right and, below it, a list of editable contact information where name, job title, address, phone, fax, e-mail and website are to be inserted. The visual display of the card template lends itself for identity interpretation through the connotations of their appearance. The particular kind of identity and lifestyle invoked here is clearly connected to a business context yet also rather vague and generic; the globe and the green line could, for instance, connote environmental-friendliness, or globalisation, or infrastructure, or ‘internationality’. As the semiotic elements carry so little specific connotative value, the globe mainly come to serve as visual decoration. Thus, the graphic appearance of this template provides users with a generic yet decorated business style identity.

The second template, the card for technology business, has a thick black “wave” covering the bottom part, while an orange-and-black logo on the upper-left part of the card provides users with a social role within “technology consulting”. To the right, “[Personal name. M. Family name],” in big orange fonts, requests users to edit the templatised text with their own personal information and in black text below also provide other conventional contact information. Thus, this card endows the user with a social position within a specific field of business, that is technology consultancy. The card resembles the first in its appreciation of visual decoration and colour but also in terms of the overall sense of genericity in its visual display—the card affords graphical marks for identity expression in a taste preference palette that nobody is likely to find either particularly appealing or particularly appalling. The lifestyle and social identity this card provides can hence be characterised as a generic, decorated tech-business style.

The third card, “business card for small company”, has a different visual display from the first two as the background is not unmarked white but a black-and-white photo of a cup of coffee. It also suggests a company title in line with this: “[Fourth Coffee]”. The templatised text also suggests a specific social role: “[Chief executive officer]”. This card thus involves a tension between the generality of the label (“business card for small company”) and the specificity of the verbal and visual information displayed (coffee business). Users are thus suggested to express themselves through coffee: either invoked as a connotation of yet another highly generic lifestyle or as a specific denotation of the business. This template thus models card holders as visually oriented coffee-appreciators with a “fresh” business style.

The card listed fourth, another “general business card”, is the template used by the informant. This card features purple background shading from light purple to the left side to darker purple at the right. This could be seen as a connoting a more informal and casual style, perhaps even more feminine. It does not include any pictorial elements beyond letters and background, and hence, the card offers no particular references to lifestyles or social identities through visual imagery. Compared with the other cards, the decorative preferences are also more downplayed. Still, as previously claimed, this card also suggests a highly generic business identity.

The fifth card is different from the others in terms of being labeled “appointment card” (“avtalekort”). On a white background with a vertical blue line to the right, “[Supplier name]” functions as heading in unmarked fonts, with conventional contact information in black unmarked fonts below. “Your next appointment” then follows, and at the bottom a templatised notion that “Cancellation must take place at least 24 hours in advance. Thank you.” Users are here thus provided the social identity of a supplier accompanied by suggestions for the conditions for appointments. In terms of visual expressions, this card carries little visual embellishment except from the coloured blue line and the blue font. Its lifestyle connotations thus point to a rather traditional and formal conservative business style.

All five templates were considered by the informant-designer as she scanned through them in order to find the most apt card for “Hilde”. She first paused at the green general card and opened the template before immediately rejecting it with an affective exclamation—“oh no!” She went on to open all the other templates and considered them by shifting between windows. The coffee template (“No! Can’t have coffee!”), the blue appointment template (“Too boring”) and the technology template (“Very technical”) were all expressively rejected because of their connotations. She finally settled for the purple general business card, although not very happily: “I think it has to be this one”. Hence, the style of the selected template does not represent the informant’s preferred choice, but rather the least dispreferred style of the otherwise conservative and embellished yet bland templates provided by Word.

Summing up, all of the five available templates provide users with identities clearly connected to social practices of business, and to place themselves stylistically in a rather conservative business world with a certain taste for visual décor. The appearances of the cards seem to aim at including as many users as possible by not excluding them through hinting to specific interests or lifestyles beyond business, and the templates thus give preference to generic business styles. This style is, however, not to be considered as ‘neutral’ but as a visual display of one particular conceptualisation of ‘neutral’. The somewhat embellished yet vapid business-like style is what Microsoft has decided to templatise and thereby naturalise as commonsensical style for business cards. Because this style is what the templates afford, it is elevated into the social position of standard. Consequently, when the style of Hilde’s appears rather generic, it is also because this is the only available set of styles in Word’s business card template collection.

Third, I consider how the styles and identities in Word’s business card templates are framed by the styles of the interface of Word, more specifically the interface of Word’s template collection, shown in Figure 8.3.

In Word for Windows 2010, the interface of the document templates is divided into four main areas: Interface heading (at the top), navigation menu (to the left), templates (in two sections at the center) and a document preview (to the right). The heading section is mainly an orientation to users on what content this interface offers. The left menu is mainly for navigating within the template interface and for performing common operations like saving and printing. The section to the right offers users a preview of the template they are about to select; almost like a window into the next window. The most salient part, however, is the template collection in the center of the semiotic space. Overall, the spatial division of the interface is clearly based on functions and tasks to be performed. It thereby models the user as practical and task-oriented, in line with how, for instance, Fuller (2003) has previously described the program.

The interface is also a multimodal display whose appearance is interpretable to users as a set of style models. This includes the colour palette, which here mainly includes white (background), grey (menu background), black (captions), dark yellow (the ‘file’ icons and marker of most recently single clicked item) and blue (the ‘wave’ in the down right corner, icons, and menu bar). The colours are mostly flat and unmodulated (cf. van Leeuwen, 2011), and the overall impression is a downplayed and rather unmarked style. In sum, the connotations of the colour palette of the multimodal Word interface thus promote a rather conservative style, with little room for aesthetical surplus beyond mere decoration.

The available templates are displayed as small multimodal clusters with an abstract image (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006) at the top and a small caption below. The most unmarked template is, unsurprisingly, the empty document, which is signalled through its placement in the visual arrangement at the top left. The display of the other templates is orderly arranged on horizontal and vertical lines. Read from left to wright and down, the templates appear in this order:

Postcard, Agendas, Books, Brochures, Business cards (”visittkort”), Calendars, Cards, Diplomas, Diagrams, Envelopes, Faxes, Flyers, Forms (”skjema”), Invites, Invoices, Labels (”etiketter”), Letter heads, Letters, To-do-lists and other lists, Memorandums.

The organising principle behind this order is rather unclear. It is not alphabetical, as the initial letters on the first two rows are P-A-B-B-V-K-K-D-D-K. Neither is it likely to be based on frequency. The appearance of visual order is thus not matched with any obvious conceptual order. Rather, it is like an office shelf on which files, over the years, have been put back in random order from a logical point of view but still visually appear as neatly organised. The most striking feature is, however, the multitude of templates. The more, the better seems to be the main statement of the connotations of the display, and thus also of the ordering. This also points to how the interface models the role of templates: templates are presented as the starting point for any imaginable type of writing task in Word.

The template captions are nominal groups in plural form naming genres and formats. The genres and formats enter into the writing practices of one particular social practice: The office. The users of Word templates are thereby accordingly modelled with social identities as (home) office workers. The office context is also reinforced by the visual icons of each template, which are abstract visual representations of office genres, such as letters, cards, envelopes, lists and so on. Some of the icons (e.g. postcards, diagrams, letterheads) are, however, not assigned with a visual image of a particular document format but with the yellow file icon well known from Microsoft Office. This pictorial element thus reinforces the user’s identity as placed in the social practices of office management and business.

Summing up, the interface of Word’s business card template collection shows that the business card templates are embedded in particular sets of ideas and norms about writing. The connotations of the interface as visual display model the user as a conservative and task-oriented office worker who does not require aesthetic surplus or fun. Rather, the interface serves to display a conceptualisation and model of how to effectively conduct office work by visually and verbally drawing on metaphors from the paper-based office. This involves selecting a template for any kind of office genre one is able to think of from a visually ordered, but conceptually unordered collection. The identity ideas of this interface model users as business people who do not wish to express individuality or lifestyle through their documents but are task-oriented servants of the office. This casts additional light on the style of Hilde’s business card: the style of her card reflects and is reflected by the style of the interface.

In this fourth and final step I discuss how the cultural context frames individuals’ writing in Word by considering how Microsoft presents document templates.

Microsoft today provides a broad array of templates online. The company’s templates are unambiguously located within the world of the office. This is evident from the examples they use in the promotions of the templates on their website: “monthly report, a sales forecast, or a presentation with a company logo” (Microsoft, undated A) and “agendas, cover pages, brochures, invoices, pamphlets, letters, certificates” (Microsoft, undated, B). Because the social practices these templates are provided for are office and business practices, the templates also serve as materialised conceptualisation of how Microsoft interprets the styles of this practice, and how it enforces this particular style as standard and rule by templatising it. Thus, the business card in Figure 8.1 does not mainly convey the informant’s preferences for an apt multimodal expression of Hilde’s identity but, rather, Microsoft’s preferences for an apt multimodal expression of a standardised business identity.

Microsoft presents its Word templates with the promotional statement that “[a]ll the formatting is complete; just add your own content” (Microsoft, undated, B). This claim rests on a conceptualisation of communication in which it is possible and desirable to separate form (the materiality of the appearance) from content (the conceptual ideas to which the appearance refers). This conceptualisation is also evident in the business card example in terms of how Microsoft provides visual settings and pictorial elements, while the user is requested to insert the verbal information that the template prescribes. This view also connects with Microsoft Words historically developed division of labour between the mode of written language and other visual modes: writing is for representation of content, while images and graphic elements are for making written text looks more aesthetically appealing (cf. Kvåle, 2016).

This division of semiotic labour has implications for semiotic power and control. Through its document templates, Microsoft holds control over the visual appearance of semiotic displays by setting the standard for the styles of documents. Users’ expressions are consequently, through the templates, driven into compliance with the software-set standards, as shown with Hilde’s business card. Users are provided with the means for designing their texts as ‘professional’ displays but are constrained to inserting semiotic elements into the program’s ready-made design. Hence, Microsoft has the power to control visual form and distribution of content, while the user is provided with power to decide on some of the verbal expressions.

Summing up, the identity expressions present on Hilde’s card are not only materialisations of design choices of the card designer or of the templates’ style or of the interface of Word as a style model. They are also materialised instances of the broader social process of semiotic and aesthetical standardisation of communication. Because of Microsoft’s total market dominance in office and everyday application software, the company is a globally powerful normative agent in this process through deciding and defining what styles and visual appearances mundane expressions should appear in.

Since its launch in November 1983, Microsoft Word has become a global superpower for writing whose norms and styles are taken for granted. It is used all across the world in a broad range of social practices—education, public institutions, corporate organizations, politics and private life. Whenever social actors are to compose a text in which written language is an important mode of expression, Word can be taken for granted as the obvious choice of software. The look of an ‘ordinary’ text is the look of a Word document, and writing with Word is the cultural emblematic form of making unremarkable marks.

This chapter has, with the design of business card as example, shown how the style of a business card display is not merely interpretable as a more or less apt expression of the identity of an individual but, rather, as an illustration of how Microsoft conceptualises the most apt expression of a business identity. Microsoft’s templatised style involves aesthetic and semiotic preferences in which the visual mode functions as décor, while the verbal mode is for expressing content, more specifically the particular content that Microsoft through its templates has given preference to. Users are in Word modelled as task-oriented workers with little desire for expressing individuality or lifestyle tastes but as compliant office employees who happily let other hold the power and control over the visual appearances of their documents. Microsoft Word’s document templates thus serve as social, semiotic, technological sites where the software’s norms for the style of identity expression asymmetrically intersect with users’ norms.

The business card example discussed here is not at all a unique case and can serve to illustrate the some of the social and semiotic implications of the increasing use of templates in society. The ongoing templatisation of communication is not merely a matter of technological and semiotic change but first and foremost of social change, in particular, the broad social tendency of standardisation. Theo van Leeuwen, who together with David Machin has shown how the international Cosmopolitan magazine involves global standardisation and homogenisation in media (Machin and van Leeuwen, 2004), claims that “[e]verywhere there are fewer (and more powerful) procedures and formats and templates, and more (but less powerful) discourses. Everywhere, there is generic homogeneity and discursive heterogeneity” (van Leeuwen, 2008: 4). This also pertains to Microsoft Word. The making of a Word-aided business card involves, as shown, an asymmetrical negotiation between users, templates and software in which users’ preferences become subservient to the standardised and generic preferences of the templates and software.

Adams, C. (2006). PowerPoint, habits of mind, and classroom culture. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(4), 389–411.

Arola, K. L. (2010). The design of web 2.0: The rise of the template, the fall of design. Computers and Composition, 27, 4–14.

Bertelsen, O., and Pold, S. (2004). Criticism as an approach to interface aesthetics. In Raisamo, R. (Ed.) Proceedings of the Third Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 23–32.

Bouvier, G. (2012). How Facebook users select identity categories for self-presentation. Journal of Multicultural Discourse 7(1): 37–57.

Djonov, E., and Van Leeuwen, T. (2011). The semiotics of texture: From tactile to visual. Visual Communication, 10(4), 541–564.

Djonov, E., and Van Leeuwen, T. (2012). Normativity and software: A multimodal social semiotic approach. In S. Norris (Ed.), Multimodality and Practice: Investigating Theory-in-Practice-Through-Method (pp. 119–137). New York: Routledge.

Djonov, E., and van Leeuwen, T. (2013b). Bullet points, New writing and the marketization of public discourse. A critical multimodal perspective. In E. Djonov and Z. Sumin (Eds.), Critical Multimodal Studies of Popular Discourse (pp. 232–250). London: Routledge.

Djonov, E., and Van Leeuwen, T. (2013a). Between the grid and composition: Layout in PowerPoint’s design and use. Semiotica, 197, 1–34.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. New York: Routledge.

Fuller, M. (2003). Behind the Blip—Essays on the Culture of Software. New York: Autonomedia.

Fuller, M. (Ed.). (2008). Software Studies—A Lexicon. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1986) [1979]. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (Ed.). (2009). The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C., and Kress, G. (2003). Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2006). The rhetoric of PowerPoint. Seminar.net. International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 2(1), 1–17.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2006) [1996]. Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

Kvåle, G. (2016). Software as ideology: A multimodal critical discourse analysis of Microsoft Word and SmartArt. Journal of Language and Politics—Special Issue on Multimodality, Politics and Ideology, 15(3), 259–273.

Machin, D. (2004). Building the world’s visual language: The increasing global importance of image banks in corporate media. Visual communication, 3(3), 316–336.

Machin, D., and van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Global media: Generic homogeneity and discursive diversity. Continuum, 18(1), 99–120.

Machin, D., and van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Language style and lifestyle: The case of a global magazine. Media, Culture & Society, 27(4), 577–600.

Manovich, L. (2001). The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Manovich, L. (2013). Software Takes Command. New York: Bloomsbury.

Meyer, R. E., and Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52.

Microsoft (n.d. b). Where Do I Find Templates? https://support.office.com/en-GB/Article/Where-do-I-find-templates-ed48c0b2-b98c-49b7-abbf-48a76ae24789, last read 03/21/2016.

Microsoft (n.d. a). Create a Template. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/Create-a-template-86a1d089-5ae2-4d53-9042-1191bce57deb, last read 03/21/2016.

O’Halloran, K. (2009). Historical changes in the semiotic landscape: From calculation to computation. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp. 98–113). London: Routledge.

Oxford Dictionary (undated). Business Card. Awww.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/american_english/business-card, last read 03.22.2016.

Pold, S. (2008). Preferences/ settings/ options/ control panels. In M. Fuller (Ed.), Software Studies—a Lexicon (pp. 218–224). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Poulsen, S. V. (2015). Exploring meaning potential in the Instagram UI—a social semiotic-media archaeological approach. Paper presentation at CMC Seminar, SDU Odense, 3.12.2016.

Tufte, E. R. (2003). The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint. Cheshire: Graphics Press.

van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing Social Semiotics. London: Routledge.

van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Leeuwen, T. (2011). The Language of Colour. An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

van Leeuwen, T., and Djonov, E. (2013). Multimodality and software. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (unpaginated). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

van Leeuwen, T., Djonov, E., and O’Halloran, K. L. (2013). David Byrne really does love PowerPoint: Art as research on semiotics and semiotic technology. Social Semiotics, 23(3), 409–423.

Zhao, S., Djonov, E., and van Leeuwen, T. (2014). Semiotic technology and practice: A multimodal social semiotic approach to PowerPoint. Text & Talk, 34(3), 349–375.