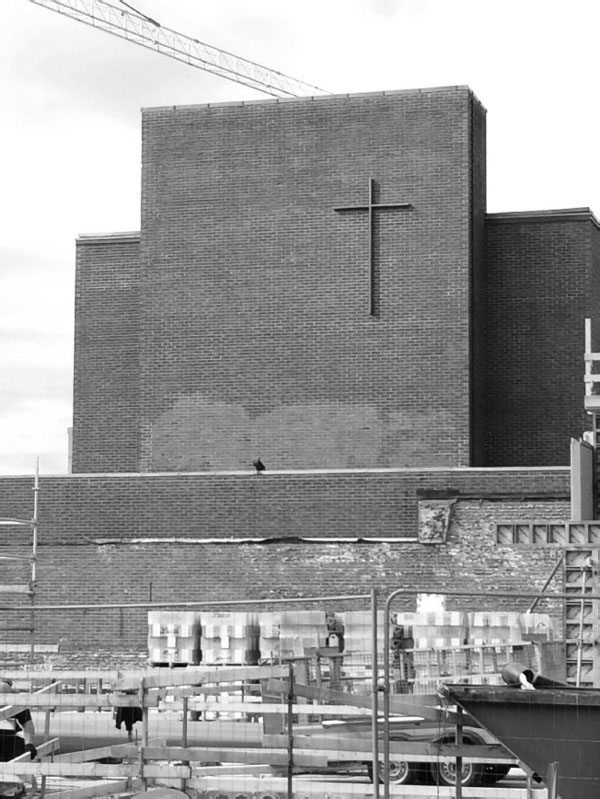

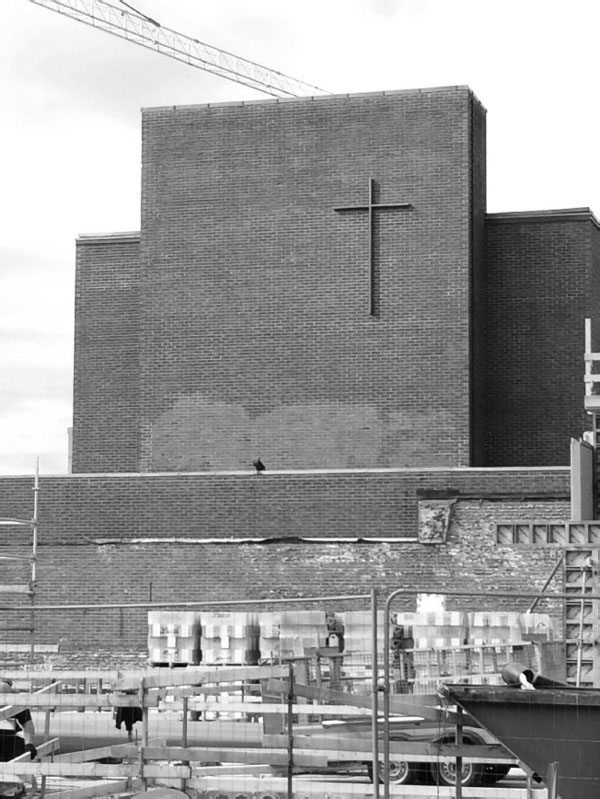

Figure 11.1 The Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Kristiansand. Photo by Anne Løvland.

The increasing diversity of religions and world views in the Western world has led to many controversies over religious buildings and other religious symbols, not least in Europe. Media reports and surveys tell tales of confrontations and general scepticism, especially to manifestations of immigrant-based religious minorities. In this article, we ask how people express opinions on certain religious visual traces in the public space, when they are actually looking at them. Our main hypothesis is that people will react more positively or nuanced when they are asked in such a context, compared to when they are asked in a more abstract situation.

Our definition of a public space is not very original. For us, a public space is an area that is, in principle, open and accessible for all. Streets, walkways, public squares, parks and beaches are typical public spaces. Libraries and certain other public buildings may also be public spaces in some instances, but in this project, we restrict ourselves to outdoor areas. Symbols visible on the outside of buildings are also parts of public space.

We consider our study a pilot study, which should be followed up by more comprehensive studies. We carried out 21 interviews on the street near three religious symbols, two crosses on brick walls and a sign outside a house showing a silhouette of a mosque. The study uses a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods. The interviews were semi-standardised, with open questions. All interviews were conducted during the same week, in September 2014, and each interview lasted from two to four minutes. We approached people passing by, presented ourselves as researchers from the University of Agder and asked if they could spare a couple of minutes for a brief, simple interview. We did not mention the topic when introducing ourselves. A few (less than ten) excused themselves, usually because they were in a hurry, but a large majority responded positively. At all sites, we had a roughly similar representation of age groups from early 20s to 60 to 75, and men and women were more or less equally represented in the sample. We did not ask for their occupation. We asked whether the respondents considered themselves religious, and also whether they were active in organised religion. In the total sample of 48, 20 characterised themselves as religious. Twelve of these 20 were active in religious congregations or organisations. Only two in the sample were Muslims. These numbers reflect the comparatively widespread Christian activity in the region.

Crosses on brick walls and a sign showing the silhouette of a mosque are physical traces of a relatively permanent nature, more permanent than, for instance, chalk letters on a blackboard or words on a PC screen. The traces that we studied can be removed, or, in the instance of one of the crosses, hidden by means of cement, but that would demand some effort. The creators of the traces may have left the buildings, but their work is still visible. When studying how people perceive signs in an urban space, it becomes quite obvious that the social context surrounding the physical traces is highly relevant for the way they are interpreted. The authors of this article are of the opinion that this fact makes interdisciplinary cooperation very important, not least between social semioticians and sociologists (Løvland and Repstad, 2014a). Social semioticians focusing on material objects, regardless of whether they are called signs, traces or symbols, need sociological concepts and perspectives in order to improve their analyses of contexts, and sociologists often have a rather primitive conceptual apparatus for analyzing and interpreting non-verbal phenomena. When it comes to the field of religion, there are important processes of aestheticisation in many countries. Religious life, both inside and outside religious institutions, is becoming more sensory and less cognitive and dogmatic. Processions are getting longer; sermons are becoming shorter. Several recent empirical studies from Norway conclude that dogma, theology and confessionalism seem to become of lesser importance in religious life, whereas materiality, sensuality, positive emotions, good experiences, in short, a feel-good dimension is becoming more central. As a part of this process, religious expressions are becoming more multimodal (Løvland and Repstad, 2014b). This trend underlines the need for increased cooperation between social semioticians and sociologists.

An early example supporting this point of view can be found in the now-30-year-old introductory chapter in the book The City and the Sign. An Introduction to Urban Semiotics, edited by Mark Gottdiener and Alexandros Lagopoulos (1986). In the introduction, the editors argue for establishing what they call a socio-semiotics, where the semiotic analysis includes a notion that culturally specific value systems underlie all forms of semiotic expressions. These value systems can contain religious explanations, philosophical discourses and scientific theories. According to the authors, “socio-semiotics, as we understand it, is a materialist inquiry into the role of ideology in everyday life” (Gottdiener and Lagopolous, 1986: 14).

Even if the social dimension can be found also in more recent social semiotics, the theoretical model presented by these American scholars appeals to us, partly because they are early and explicit proponents of cooperation between social semiotics and sociology but also because their model has been developed within the field of urban semiotics, and we have studied religious traces in urban settings.

Gottdiener and Lagopolous’s model of analysis consists of a series of combined aspects or dimensions. The model is based on a traditional concept of signs with an expression side and a content side (Hjelmslev, 1961). They then break each of these concepts into two levels, corresponding to their ‘form’ and their ‘substance’. Table 11.1 shows the relation between Louis Hjelmslev’s dichotomy, Gottdiener and Lagopolous’s elaboration of the categories and our own description of the dimensions that we use in the analysis, based on Gottdiener and Lagopolous’s model.

Gottdiener and Lagopolous suggest that the analysis of meaning-making elements in an urban space should consist of four aspects or dimensions working together: the physical expression, the meaning created by the expression, the material situation surrounding the expression and a non-codified cultural frame making the sign possible. They claim that it is mainly the formal components which are usually understood as relevant by traditional semiotics, and they stress the importance of the substantial elements, as “signifiers and signifieds are themselves connected relationally and functionally to their respective cultural and material contexts”. The substance of the content consists of a non-codified ideology which is a part of the culture where the sign emerges or exists. On the expression side the substance is the material situation, which contributes to the meaning-making but which in itself is not part of the trace (Gottdiener and Lagopolous, 1986: 17).

The contextual part of the model seems to have many similarities to Michael Halliday’s description of “the context of culture” and “the context of situation” (Halliday, 1999), but, unlike Halliday, Gottdiener and Lagopolous do not relate the model only to the language system, and their model is therefore more relevant to semiotic expressions that are not necessarily linguistic. Gottdiener and Lagopolous’s four levels structure our analysis of religious signs in public spaces, and it is also relevant for how we analyse the informants’ understanding of the religious expressions. We now present the physical expressions of the signs in our study and then describe the general meaning of the signs. Following this, we describe the material situation of the signs, and finally we present relevant aspects of the cultural context.

Hjelmslev |

Gottdenier & Lagopolous |

Dimensions for analysis |

||

Substance |

the non-codified cultural frame |

|||

Content |

Form |

the meaning created by the expression |

||

Expression |

Form |

the physical expression |

||

Substance |

the material situation surrounding the expression |

Our empirical study focuses on signs related to two different religions, Christianity and Islam. We study people’s reaction to crosses, and to a sign showing a picture of a mosque. The two single crosses are relatively large. One is made from metal and mounted on a brick wall. The colour of the cross is metallic. The wall is the side wall of a church, but except for the cross, there are no other traits on that wall indicating that this is a church. It is simply a large and tall brick wall with a cross in the middle and no other decorations or windows. The other cross is built into the facade beside the entrance. This cross is smaller than the other one, and it is made from bricks of a slightly different shade of red than the wall. This cross is more integrated in the building itself, but it is clearly visible to passers-by. The mosque sign is the smallest symbol, about 60 by 30 centimetres. It is a painted metal sign, fastened on a wall. The sign, painted in black on white, shows a black silhouette of a traditional mosque with a minaret, together with the word Moské written in both Latin and Arabic script. All three symbols are easily visible from the street.

The cross is the most common Christian symbol of all. It is found in all Christian churches, often as the main principle of architecture of the church building itself. Crosses are found on several church spires, on the pulpit and on the altar, on Bible covers, on graves and many other places. Although it was already used in the second century, in the first three centuries of Christianity it did not yet have the importance it was to acquire later. The crucifix became common from the fourth century onwards. The empty cross came into Christian use earlier than the crucifix, a cross with a three-dimensional representation of Christ’s body. The empty cross was used as a reminder that Christ had left the cross and triumphed over death. In Protestant countries like Norway, the empty cross has been much more common than the crucifix, and both our crosses are empty. Especially in Protestant low-church movements, the crucifix has been looked on with scepticism as a kind of Catholic deviation, although recently a more ecumenical sentiment has weakened this skepticism. In contemporary church life, the cross has generally become more abstract and stylised. Hence, the two crosses that we have used in our study are both abstract, so-called Latin, crosses, that is crosses where the vertical line is longer than the horizontal one.

A mosque is a place where Muslims worship. In many places, the mosque has several additional functions. In Western Europe, a mosque often serves as a community centre. Mosques were first built on the Arabian Peninsula, and an old Arabian building style has inspired mosques around the world for centuries. In Norway and other Western countries, a combination of lack of resources and a wish to adapt to the new host country have had as a consequence that there are mosques also found in buildings typical for this country.

For our pilot study, we chose two crosses in the city of Kristiansand and one sign in the city of Mandal, indicating a mosque. All three symbols were situated in the town centres. We did our first interviews on the walkway across the street from a cross high up on a brick wall. As we have already mentioned, the cross is easily visible, but you have to look up to see it. The building is the place of worship for the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Kristiansand, one of the largest Christian denominations in the country outside the Church of Norway.

Our second set of interviews took place across the street from the entrance to the Advent Church in Kristiansand, the church of a much smaller denomination than the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church. This is where Seventh-Day Adventists gather to worship. Even if the cross here is more visible than the letters Adventkirken, there is a closer connection between the symbol and a specific institution than is the case with the Lutheran Free Church. We wondered whether some of the informants would have a critical attitude to the Adventists, in particular, as this denomination traditionally has been criticised from a majority Lutheran point of view. However, nobody raised such confessional issues; everybody talked about the cross in general. This may be because of a general de-confessionalisation in Norway, a weakened interest in and knowledge of dogmatic differences (Repstad and Trysnes, 2013).

The third research site was outside the mosque in Mandal, where only the small sign above the entrance identified the location as a mosque. The house itself is a traditional white-painted house built in wood, quite common in the region. It was previously used as a private residence, so the sign is the only indication that this is a religious building. The mosque in Mandal is situated on a quiet street but only about 10 metres from a main street with many pedestrians. So, we placed ourselves at the corner of these two streets.

Both Kristiansand and Mandal are situated in the southernmost part of Norway, in a coastal region which is sometimes referred to as Norway’s Bible Belt. The region has been and still is, to some extent, a region with strong Christian lay movements and minority churches. Churches and other religious events attract higher attendance here than elsewhere in Norway, and surveys also show that active Christians in this region, called Sørlandet, are generally more conservative than active Christians in other parts of the country (Repstad, 2014). Kristiansand has about 85,000 inhabitants; Mandal, about 15,000.

Figure 11.1 The Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Kristiansand. Photo by Anne Løvland.

Figure 11.2 The Seventh Day Adventist Church in Kristiansand. Photo by Anne Løvland.

Most Muslims in Norway are immigrants and the largest proportion of them live in and around the capital Oslo. The two counties comprising Sørlandet, Aust-Agder and Vest-Agder, have a proportion of immigrants from Africa and Asia close to the national average. Kristiansand is well above this average and Mandal close to it, while the more sparsely populated areas have few Muslims (Østby, Høydal, and Rustad, 2013).

Norway is not among Europe’s most polarised countries when it comes to religion. The debate has been harsher a little farther south—in Denmark (Christensen, 2010; Niemelä and Christensen, 2013). However, even in Norway, the issue of visible and audible religious symbols in the public sphere has been an issue over the last ten years or so. Like many other European countries, Norway has gradually moved from a Christian majority church dominance to a more diverse situation. As early as the 19th century, a degree of Christian diversity emerged, and in the 20th century, a secular element was first introduced into the plurality, followed by several other religions outside Christianity, mainly because of immigration.

There are restrictions on religious visibility in public spaces in Norway, although the pattern is not completely consistent. The police are not allowed to wear religious dress or symbols when in uniform. In the military, turbans and hijabs are allowed, as long as the dress does not conflict with health, security and operative ability. Hence, religious clothing hiding the face or the uniform, such as niquabs and burkas, is forbidden. As for judges, there are no regulations, allegedly because the question has not yet been raised. There is no general regulation of teachers’ right to wear religious dress and symbols. This issue is left to local school authorities, if the question arises. Finally, there are no national regulations pertaining to student rights in schools and universities. Local schools seem to be oriented towards finding pragmatic solutions, although there have been one or two cases where women in niquabs have not been allowed access to exams (Schmidt, 2015: 127).

Figure 11.3 The mosque in Mandal. Photo by Anne Løvland.

Among the public, the majority seems to be rather sceptical towards people in official contexts wearing religious dress or symbols. In a survey carried out in 2012, more than 70 per cent disagreed with allowing uniformed police and judges to wear clearly visible religious clothing or symbols. As for teachers in state schools, 60 per cent disagreed (Botvar and Holberg, 2015).

Siv Kristin Sællmann is a news presenter for Norway’s major broadcasting channel, Norsk rikskringkasting (NRK). She regularly presents the evening news in Norway’s southern region—Sørlandet. In the autumn of 2013, she was asked by the head of her department to stop wearing a cross on her necklace when presenting the news. The cross was small—14 millimetres long. The background was said to be repeated protests from a single viewer (Sandberg, 2013). When the story was reported in several newspapers in early November 2013, a vivid discussion started in public and social media. A Facebook page was established, named “Yes to carrying the cross whenever and however I want”. It got 123,000 likes in November 2013. The person who created the page later told the media that he was disappointed that many hateful statements about Muslims were posted on the page and that he had to delete statements of this kind almost daily (Molnes, 2013). The story about the cross shows that the appearance of religious symbols in public settings is a hot issue in Norway, as indeed elsewhere.

It should be added that there are no general restrictions in Norwegian law against religious symbols on religious buildings, or for that matter against religious sounds. In other words, there is no parallel to the Swiss constitutional ban on the construction of minarets, following a referendum in November 2009 in which a majority of 58 per cent was in favour of the ban (Langer, 2010). Nevertheless, it seems that Muslim leaders in Norway have kept a very low profile and have carefully avoided any practice that could provoke people, such as religious messages from minarets. Our own research process provides a good example of this restraint. A new mosque was opened in Kristiansand in April 2014 in an existing ordinary brick building in the town centre. The building had formerly housed a store. It has no minarets or other external traits informing people passing by that this is a mosque. Actually, there are no informative signs at all at the time of writing (spring 2016). We had to go to Mandal to find a small sign outside a house used as a mosque.

“Is a religious symbol like this acceptable or not acceptable in a place like this?” This was the question we asked after they had looked at the symbol. All informants except one expressed a positive attitude towards Christian symbols in public spaces, when they were looking at a concrete physical symbol. We then asked them why they thought so. Some were not able to provide reasons for their positive attitude, but most did. Some mentioned the argument that all religions, including Christianity, should have the freedom to be visible also in public places. Others, it was found, gave some kind of priority to Christianity, using phrases like “Christianity is our religion; we are after all a Christian country” and other statements to the same effect. “These things about religion, they become so dissolved,” one said. “We must keep Christianity as the Norwegian religion.” We did not notice any religious answers claiming that Christianity is the only true religion and should therefore have a monopoly. The arguments presented were in a sense secular and general, often referring to Christianity as a cultural and religious heritage. Only one person in Kristiansand expressed negative feelings towards all religious symbols in public places, including Christian symbols. He stated in clear and strong terms that he was against all religion because it creates conflicts.

All people outside the mosque in Mandal also supported the right of Christians to have their symbols displayed in public, so Christian symbols seem to have a strong status in Norway, at least in this region. Both in Mandal and in Kristiansand, Christian symbols have been a part of the town landscape for ages, so habit is probably part of the explanation. A quick inventory of downtown Kristiansand showed that almost 30 buildings have clearly visible Christian signs or symbols on the outside (churches, prayer houses, congregation halls, etc.).

It is not surprising that Christian signs are relatively non-controversial. Grace Davie’s notion of vicarious religion can be used as an explanation. However, the story about the TV news presenter with the cross shows that even Christian symbols can be controversial for some and in some settings. And if the Christian symbols are too dominant or spectacular, it may be that even the population in Sørlandet, the stronghold of Christianity in Norway, may voice reservations. We have some anecdotal evidence here. In 2007, a local successful businessman suggested in the media that a large statue of Jesus should be erected on a hilltop just outside the town centre. He even had the statue Photoshopped, and it was presented in several national media. The similarity to the statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro was striking. The statue dominated the landscape completely in the picture that was published. Most reactions, from politicians, media and the public, showed that people had great difficulty in taking this seriously. Later it became known in the media that the business entrepreneur, enjoying considerable success in Internet trading, had been given the idea by a communications adviser (Repstad, 2007: 120).

In Kristiansand, we asked people whether they would have the same attitude towards signs from religions outside Christianity in the public space. Note that we were standing near a Christian symbol when the question was asked, so this question was more abstract and less context-bound than the one about Christian symbols. The answers varied notably—12 informants were mainly positive, and 19 were mainly negative. Islam almost always came up in the conversation.

We use the term mainly positive or negative, as some expressed doubts and did not conclude categorically. Only one informant clearly indicated that he supported a legal ban on religious symbols. He was actually opposed to all kinds of religious symbols in public. As mentioned, several expressed scepticism towards non-Christian symbols. This was the strongest statement: “I see so many people wearing headscarves, and I am so sick and tired of it that I could vomit.” The majority was more diplomatic but voiced different degrees of scepticism. One who explained his positive attitude to Christian symbols with the statement “We live in Norway” answered as follows to the question about symbols from other religions: “No, I would not [be as positive]. We must protect our values. They do not have to advertise it.” Another said, “I must admit no, I am quite anchored in Christianity.”

Some of those who accepted non-Christian symbols in the public sphere gave no reasons for this. Most of the informants did. One voiced a kind of inclusive theology, claiming that deep down people connect to the same god. Two kinds of reasons were more common: a principle of equal treatment of religions, and a statement that Norway has become a multi-religious country. Quite a few added some qualifications. A woman outside the Lutheran Free Church said, “There is so much diversity here in Norway now, so we just have to accept it.” Then she added, “As long as they behave decently and do not threaten us.” Another positively-minded woman said, “We have a democracy, but I do not have a heart-to-heart relationship to this. I do not like it when they scream.” We did not follow up on what she meant, but one possibility is that she referred to proclamations from minarets.

In our opinion, the most interesting finding of our study was that people were much more positive towards signs representing religions other than Christianity when we were actually standing near the mosque, compared to when the question was raised in a more abstract setting. Only one of the 17 informants we met on the street outside the mosque in Mandal clearly stated that signs such as the rather modest one we were looking at should not be allowed. He said, “I would have had it removed if it had been near my own house.” All the others were more positive. Some were clearly in favour of religious pluralism in the public space. One man, engaged in Christian diaconal work, said, “Yes, we must use our wisdom. We have a multicultural society now. Why would we be so insecure about our own identity? We must have equal treatment.” Others stressed that they were positive to this specific sign, underlining that it was modest and small. Some of these combined this attitude with voicing scepticism towards more spectacular or dominant religious expressions. One informant said, “This is a small sign. I would have protested if it had been enormous.” Another informant said she would not like a minaret in Mandal, but she had nothing against this sign, as it had a function. A third informant said, “I do not react to this, but I am not enthusiastic about Islamisation.” A woman, a refugee who had converted from Islam to Christianity, expressed strong negative general feelings against fundamentalism, but she said that it is a democratic right to display such signs as the one we were looking at.

At least as a working hypothesis for further studies, it seems that manifestations of the alien other emerge as more problematic when people think in the abstract than when their senses are confronted with physical artefacts.

It should be underlined that the sign outside the mosque was rather small and inconspicuous. This means that larger and more eye-catching (as well as ear-catching) symbols might have been met with more negative reactions. As we have indicated, some informants in Mandal who voiced support for the sign distanced themselves from more spectacular signs, minarets and so on. Maybe this is an example of a more general and interesting observation, namely that looking at specific symbols may de-dramatise people’s reactions. It is likely that questions asked in more abstract situations facilitate more threatening connotations. When the informants in our study only reacted to the question “Would a symbol from another religion [other than Christianity] be acceptable?” they related to a linguistic expression lacking what Roland Barthes called the illusion of presence. The personal and cultural meaning—often media-shaped—that many Norwegians attach to “other religions” will therefore become more important. Questions about mosques, minarets and Islamic symbols may evoke feelings of being threatened by Islamist movements, perhaps especially among people who have little or no personal connection to Muslims or Muslim symbols and only know such phenomena from the mass media. Even if there are exceptions, many mass media stories convey negative pictures of ethno-religious minorities and immigrants in general (Døving and Kraft, 2013, Figenschou et al., 2015).

Theoretically, the connection between people’s own religion and their attitude to other religions can be thought about in two different ways. Those who have strong religious convictions may be restrictive to the space given to other religions. However, they may also be more tolerant when religion means something to them, and think that others should have the same opportunity as they have themselves to practise their religion.

Our material is of course limited, so we cannot make strong conclusions here. We see both kinds of reasoning in our empirical material. In the abstract, there was a slight tendency for religious people to be more sceptical to the appearance of other religions in public when we asked them out of context. On the other hand, during our interviews outside the mosque in Mandal, all the people who considered themselves religious accepted the specific sign outside the mosque.

Obviously the sensory experience of the crosses and the mosque sign was not decisive for all informants. Some had thought about the issue in advance and had fixed attitudes, one way or the other. Both those who talked about equal treatment and multiculturalism as the person who claimed that all religion leads to conflict seemed to have talked about the topic in the same way before. However, a majority seemed to be hesitant, many of them also ambivalent, especially when we asked about the mosque sign, and in these cases, our impression was that the material, sensory situation made an impact. It is not surprising that there is ambivalence in these matters. Norwegians live in a comparatively egalitarian culture. It is often illegitimate to clearly voice that some people are better than others (Skarpenes, 2007). On the other hand, egalitarianism can lead to a demand for similarity (Gullestad, 1991). It is perhaps more than a pure linguistic coincidence that, in Norwegian, there is one single word for equality and similarity—likhet.

To be honest, our main hypothesis was not crystal clear when we started our interviews. Initially, we had an inductive approach. However, quite soon we became aware of the tendency that people were more nuanced and more positive to religious symbols in public spaces when they faced concrete examples of such symbols than when they were asked outside such a concrete setting. As we have shown, the hypothesis was strengthened by the results of the study. We try to make sense of these results by using three theoretical perspectives: Grace Davie’s concept of vicarious religion (2000, 2007); the importance of the material situation, as expressed in Gottdiener and Lagopolous’s version of social semiotics (1986); and an application of Allport’s contact hypothesis (1979).

For many Europeans, Christian symbols and buildings in public places form an important part of their so-called vicarious religion. This concept was coined by sociologist of religion Grace Davie (2000, 2007). She states that in many European countries, not least in the Nordic countries, organised religion (in practice especially Christianity) is performed by an active minority on behalf of a much-larger number who, implicitly at least, not only understand and tolerate but even approve of what the minority is doing as well. They may not use the symbols or pay much attention to them, but they like them being there, and they certainly want to maintain the right to have them there, in public spaces. So, in European countries there are reasons to expect that Christian symbols will be less controversial and more taken for granted than the symbols of minority religions. This perspective explains the more positive attitude to Christian symbols compared to non-Christian when people are asked in the abstract. However, to explain the relative positive attitude to the sign outside the mosque in Mandal, we must go to other theories.

The result that asking in context gives more nuanced and positive answers than asking in the abstract, can be explained by the insight that the material situation as well as the cultural context contribute actively to the way people understand and interpret signs. When the signs are experienced in the urban space several aspects or dimensions balance each other. The nice and typical small-town street with cobblestones, the mosque being a white wooden house in a row of similar traditional houses, the sign mounted in wrought iron, very familiar in old towns in Sørlandet, well-known for inhabitants and common in tourist brochures—all these traits tend to balance the more fearful attitude that may be found in the value system of some informants, maybe inspired by media’s sometimes stereotypical coupling of Muslims with crimes and extremism. The sign can be said to de-dramatise possible connotations that may be evoked when the topic of Muslims is presented in the abstract. Similarly, it is possible that some people’s attitudes and values that are critical to religion are weakened by a material situation when they bicycle past crosses on walls in a public street without really noticing them. Without this material frame and without the concrete physical sign to relate to, the established signification and the informants’ cultural values are more dominating. A linguistic sign thought into a mental context is not in the same way anchored in the material situation.

We would like to give one more example of how we can use theoretical resources from sociology and social psychology to make sense of our claim that stereotypes can be weakened, at least for some people, when they find themselves face to face with concrete material expressions. We suggest that the well-established contact hypothesis from social psychology can be transferred from contact with other people to contact with physical, material objects. The contact hypothesis was introduced by Gordon Allport in his landmark volume The Nature of Prejudice (1954/1979). In its original form, it is a very simple hypothesis: contact between a member of an in-group and a member of an out-group tends to improve the attitudes of the former towards the latter by replacing in-group ignorance with knowledge that disconfirms stereotypes. The hypothesis has been criticised and modified. Allport himself identified several conditions that he believed would enhance the beneficial effects of contact, such as status equality and institutional support. Despite criticism and reservations, the contact hypothesis seems to survive and be quite robust. This is the conclusion of Pettigrew and Tropp (2006), based on a systematic review of more than 500 studies. According to their analysis, the more methodologically rigorous studies yield larger mean effects. One important mechanism seems to be that direct contact reduces fear and anxiety on the part of the majority, as shown in many studies, for instance a quantitative study from the United States about public exposure to homelessness (Lee et al., 2004), and a qualitative study from four European countries about relations between ethnic majority and minority groups (Binder et al., 2009). The latter study shows—not surprisingly—that prejudice reduces contact but also that contact reduces prejudice, especially when out-group contacts are perceived to be typical of their group and not an exception. Recently, the contact hypothesis has also been confirmed in Denmark, in a national probability sample. The author concludes that regular intergroup workplace contact can improve ethnic relations in contemporary democracies (Thomsen, 2012). Similar conclusions are drawn from the same material in another article. Neighbourhood contact reduces majority members’ negative stereotyping because it reduces anxiety and increases empathy (Rafiqui and Thomsen, 2014). There may also be some relevance to a finding in another Danish study. Using data from a representative survey, Lene Aarøe (2012) found that tolerance of religion in the public space depended on the salience of the manifestation of religious group membership. She found that people were less tolerant to judges wearing a Muslim headscarf than to judges wearing a necklace with a Muslim crescent. The least degree of scepticism was directed towards judges wearing a necklace with a Christian cross.

Despite the limitations of our empirical study, we think that we have found an interesting result here, namely that people with less definite opinions and attitudes in particular are influenced by the interview situation, causing people to have more nuanced and less negative views on minority symbols in the public space when they are actually looking at these symbols. How can we make further sense of this finding by using resources of interpretation from the methodological and theoretical tool boxes?

We have referred to a good many empirical studies about people’s attitudes to religious symbols. They were all collected in the abstract, in national surveys. We believe that studying this topic in a more natural context, for instance, in conversations with people actually wearing religious symbols, would elicit less intolerance. We mentioned the Swiss ban on building more minarets in the country. The results of the referendum showed that the number of votes cast against minarets was clearly highest in areas with no minarets and very few Muslims (Langer, 2010: 945). Our study is explorative, but the tendency in our admittedly modest sample is very clear: people are more tolerant when they are actually looking at a Muslim sign than when they are asked in the abstract.

It should be remembered that we were looking at a rather unspectacular Muslim sign, but such symbols are, after all, much more common in Norway than spectacular mosques with minarets. It would be interesting to follow up on our study by using larger samples and longer, more in-depth interviews. The context could also be varied, for instance by interviewing outside more spectacular mosques, as well as outside minarets, with or without calls to prayer. Furthermore, we cannot think of reasons why our finding should be valid for religious traces only. It seems like a reasonable hypothesis that we could find the same methodological variation in and out of context with other traces in the public sphere, for instance political symbols. However, the general validity of this should be tested empirically.

In the meantime, we believe it can be safely recommended that the Muslim leaders in the new mosque in Kristiansand put up at least a small sign on the outside wall to inform people that this is a mosque. It is possible that it would evoke negative reactions if a lot of very spectacular symbols of minority religions were introduced overnight in Norwegian local communities. But a relevant policy implication of our study can be formulated like this: gradually accustoming people to symbols from religions called ‘foreign’ a generation or two ago can facilitate social and cultural integration.

1This is an extensively revised version of an article titled “Religious symbols in public places: Asking people in and out of context”, published in Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 28(2) 2015, 155–170. It is printed here with the permission of the editors of the journal.

Aarøe, L. (2012). Does tolerance of religion in the public space depend on the salience of the manifestation of religious group membership? Political Behaviour, 34, 585–606.

Allport, G. (1979) [1954]. The Nature of Predjudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Binder, J. et. al. (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 843–856.

Botvar, P. K., and S. Holberg (2015). Religion i politikken—gammelt tema, nye konflikter [Religion in political life—old topic, new conflicts]. In I. Furseth (Ed.), Religionens tilbakekomst i offentligheten? [The return of religion in the public space?] (pp. 38–68). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Christensen, H. (2010) Religion and Authority in the Public Sphere: Representations of Religion in Scandinavian Parliaments and Media. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Faculty of Theology, Aarhus University, Aarhus.

Davie, G. (2000) Religion in Modern Europe: A Memory Mutates. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davie, G. (2007). Vicarious religion: A methodological challenge. In N. Ammerman (Ed.), Everyday Religion (pp. 21–36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Døving, C. A., and Kraft, S. E. (2013) Religion i pressen [Religion in the press]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Figenschou, T. U., Thorbjørnsrud, K., and Larsen, A. G. (2015). Mediatized Asylum Conflicts. In M. F. Eskjær et. al. (Ed.), The Dynamics of Mediatized Conflicts (pp. 129–145). New York: Peter Lang.

Gottdiener, M., and Lagopolous, A. Ph. (1986). Introduction. In M. Gottdiener and A. Ph. Lagopolous (Eds.), The City and the Sign: An Introduction to Urban Semiotics (pp. 1–22). New York: Columbia University Press.

Gullestad, M. (1991). The Scandinavian version of egalitarian individualism. Ethnologica Scandinavica, 21, 3–18.

Halliday, M. (1999). The notion of ‘context’ in language education. In M. Gadessy (Ed.), Text and Context in Functional Linguistics (pp. 1–24). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Hjelmslev, L. (1961). Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Langer, L. (2010). Panacea or Pathetic Fallacy? The Swiss Ban on Minarets. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 43(4), 863–951.

Lee, B., Farrell, C. R., and Link, B. G. (2004). Revisiting the contact hypothesis: The case of public exposure to homelessness. American Sociological Review, 69, 40–63.

Løvland, A., and Repstad, P. (2014a). Sosialsemiotikere og sosiologer—forén dere! [Social semioticians ans sociologists—unite!]. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 55(4), 347–360.

Løvland, A., and Repstad, P. (2014b). Playing the sensual card in churches: Studying the aestheticization of religion. In A. McKinnon and M. Trzebiatowska (Eds.), Sociological Theory and the Question of Religion (pp. 179–108). Farnham: Ashgate.

Molnes, G. (2013, December 2). Oversvømmes av hatske meldinger [Flooded with hateful messages]. Vårt Land.

Niemelä, K., and Christensen, H. (2013). Religion in newspapers in the Nordic countries in 1988–2008. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 26(1), 5–24.

Østby, L., Høydahl, E., and Rustad, Ø. (2013). Innvandrernes fordeling og sammensetning på kommunenivå [Distribution and composition of immigrants at municipal level], Report 37. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Pettigrew, T., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783.

Rafiqui, A., and Thomsen, J. P. F. (2014). Kontakthypotesen og majoritetsmedlemmers negative stereotypier [The contact hypothesis and majority members’ negative stereotypes]. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 55(4), 415–438.

Repstad, P. (2007). Gudsfrykt, nøysomhet og velstand [Fear of God, austerity and prosperity]. In A. Løvland et al. (Eds.), Gud på Sørlandet [God in Southern Norway] (pp. 120–121). Kristiansand: Portal forlag.

Repstad, P. (2014). When religions of difference grow softer. In G. Vincett and E. Obinna (Eds.), Christianity in the Modern World (pp. 157–174). Farnham: Ashgate.

Repstad, P., and Trysnes, I. (Eds.). (2013). Fra forsakelse til feelgood [From self-denial to feelgood]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Sandberg, T. (2013, November 30). En eneste henvendelse startet korsstriden [One single inqury started the conflict about the cross]. Fædrelandsvennen.

Schmidt, U. (2015). Stat og religion [State and religion]. In I. Furseth (Ed.), Religionens tilbakekomst i offentligheten? [The return of religion in the public space?] (pp. 105–138). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Skarpenes, O. (2007). Den “legitime kulturens” moralske forankring [The moral foundation of the “legitimate culture”]. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 48(4), 531–563.

Thomsen, J. P. F. (2012). How does intergroup contact generate ethnic tolerance? The contact hypothesis in a Scandinavian context. Scandinavian Political Studies, 35(2), 159–178.

***

Anne Løvland, Associate Professor, Department of Nordic and Media Studies, University of Agder, Norway. anne.lovland@uia.no

Pål Repstad, Professor, Department or Religion, Philosophy and History, University of Agder, Norway. pal.repstad@uia.no