Nastaliq calligraphy is used to convey literary or poetic meanings as art panels, posters and frescos or murals. These works place less emphasis on functional aspects of visual communication and focus on the aesthetic aspects of fine arts. In other words, Nastaliq calligraphy has traditionally been seen as an abstract art, not a means of communication with distinctive features and communicative functions. However, based on visual communication and the theory of materiality of multimodality constituted texts, letterforms can be seen as distinctive visual forms that communicate autonomous messages without dependence on language conventions.

From a superficial point of view, letterforms are rather abstract, senseless and constrained to conventions and concrete meanings in language, while through the lens of multimodal social semiotics, letterforms as visual shapes/forms are individually meaningful and structured into visual texts (Johannessen, 2010: 109). In this respect, letterforms behave as graphical forms such as logos, pictograms and every sign in visual communication. From this perspective, I examine calligraphic letterforms based on their shapes to investigate how they act as meaningful visual forms in visual communication, conveying an autonomous meaning regardless of linguistic, conventional or concrete meanings. Thus, calligraphy hypothetically can be considered a semiotic mode1 that comprises a collection of resources organised through specific principles in a specific context which is itself shaped through social interactions (Jewitt, 2009: 22).

The objective of the study is to examine the extent to which calligraphic letterforms conform to general and universal conventions and theories applied to graphic forms to understand the extent to which calligraphic letterforms can be considered visual graphic forms in their own right, independent of linguistic practices. Furthermore, the intent is to understand how traditional theories of implementation in Nastaliq, such as circle and plane and Savad and Bayaz, can be explained by applying theories and systems of analysis, particularly those used to analyse graphic phenomena.

Regardless of their conventional (lexical) meanings in language, the first step is to unleash these letterforms from conventional signifier–signified and embedded meaning in language and accept them as communicative visual forms, like graphic forms. Johannessen (2010, 2013) theorises graphic form in relation to the two distinct fields of graphology and graphetics. In the first step, I adopt a trimmed version of the descriptive scheme proposed by Johannessen (2010), which approaches shapes descriptively to distinguish graphic meanings. The schematic is oriented towards graphology, which studies “abstract potential for distinguishing graphic meaning” (Johannessen, 2013: 157). In this step, a corpus of Nastaliq calligraphy is approached through both SHAPE and ENSHAPENING. Through these systems, we can distinguish graphic forms from other visual forms as filters or strainers that purify graphic characteristics by rendering shapes into visual forms. They can also describe how the traditional theory of circle and plane in Nastaliq can be meaningful and authentic in calligraphic letterforms.

The first step is accompanied by another step in which visual forms are examined for “possibility space for graphic articulatory dynamics including affordances of the body, graphic tools and substance” (Johannessen, 2010: 157). That is, one must prove that letterforms in Nastaliq calligraphy are comparable to graphic signs or whether the basic set of conventions underlying graphic forms manifests in calligraphic forms of Nastaliq. This complementary step is carried out after the corpus study, through “articulatory graphetics” as Johannessen (2010, 2013) suggests.

The study is based on the following assumptions:

The study is conducted on a large corpus of letterforms from a popular form in Persian calligraphy, Nastaliq, for two reasons. First, Persian calligraphy has always been used for writing sublime poetry to convey valuable didactic or literary messages. Thus, a tight and inevitable relationship exists between Nastaliq calligraphy and the Persian language. Because of such cohesion and coherency, I use Nastaliq calligraphic letterforms as appropriate material for examining the extent of the letterforms’ ability to independently represent and indicate meaning. Second, letterforms in Persian Nastaliq calligraphy, in terms of performance and implementation, are constrained by principles enacted over time based on graphic aesthetic rules. This synchronic trait, an inevitable connection with language and yet a commitment to basic principles of graphics and traditional calligraphy, makes it an adequate resource from which to select samples for analysis. These materials also provide space for evaluation of the relationship between tradition and graphic conventions to illustrate how graphic conventions refer to tradition or lead to graphic conventions.

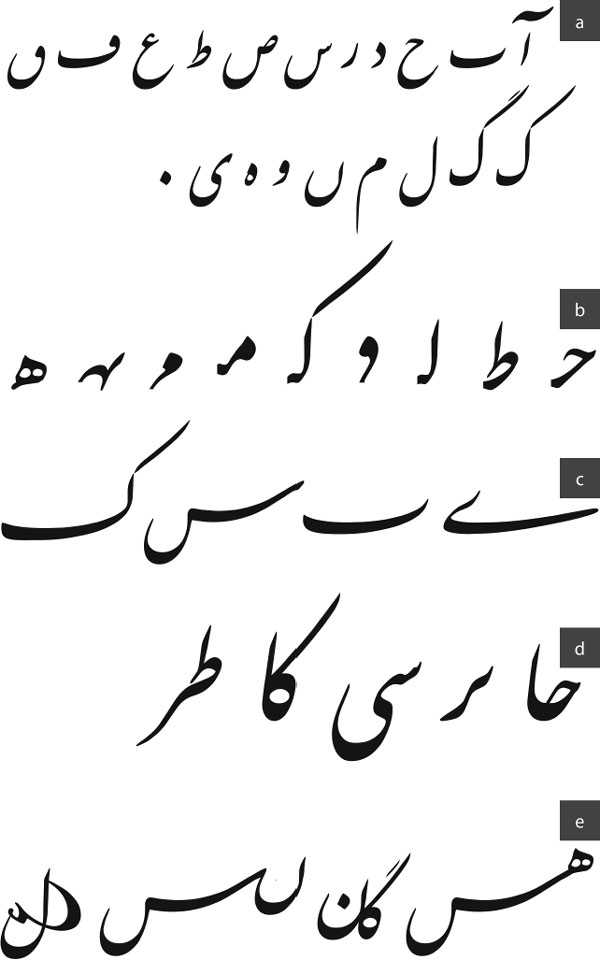

The study applies non-probability strategic sampling in materials selection. Stepwise, a corpus of 300 images of Persian calligraphy includes 19 individual letterforms2 with their extensive forms,3 18 second letterforms,4 15 compound forms5 composed of letterforms, which are meaningful in Farsi and made according to the conventional compositional rules in Nastaliq calligraphy,6 another 15 compound forms, which are made regardless of compositional principles in the calligraphy and are meaningless in Farsi, and 247 compound letterforms made of a combination of letters two by two according to compositional principles in Nastaliq.

A selection of the images (made by the author in the Chalipa artwork software) is shown as Figure 12.1.

The theory of circle and plane is based on or extracted from practical theories of implementation in Nastaliq calligraphy enacted across centuries by traditional pioneers, performers and calligraphers. This theory addresses the balance between circles and planes used in letterforms; it discusses the proportion between curved bends and straight lines in performing letterforms. I extract this notion from the complex practical discussion of “DANG and DOUR”, sixth and round (e.g. Irani, 1983; Bayani, 1984; Ghazi Monshi, 1988; Ghelich Khani, 1993, 1994; Falsafi, 2000; Barat Zadeh, 2006; Ormavi, 2006) in performing letterforms, based on the traditional belief/statement that Nastaliq calligraphy is structured on circles and that all letterforms in Nastaliq are designed based on a circle. The claim, asserted by pioneers of Nastaliq calligraphy, is that the circle is the dominant shape in heterogeneous letter shapes.

In essence, traditional definitions of Nastaliq calligraphy indirectly account for the circle as the origin of calligraphy, indicating that Nastaliq calligraphy is composed of a combination or juxtaposition of dots (which are structured based on the circle) that make lines (Bolkhari, 2006). In their analysis of different types of calligraphy and their application, Ravandi (1160, in Eghbal, 1990), Bolkhari (2006) and Heravi (1587–1670, in Ghelich Khani, 1993) mention that Nastaliq is based on the circle and if Nastaliq letterforms are analysed for curliness versus straightness, the proportion of circles is greater, always at a 5:1 ratio. Some discussions go further to glorify the circle and are prone to pseudoscience rather than theoretical discussion. For instance, in his handbook, Ravandi (as cited in Eghbal, 1990) mentions that the circle is the origin of the dot, all letters and words and even arithmetic as a whole.

In short, the theory of circle and plane that I derive from 12 crucial principles of implementation of calligraphy (i.e. composition, baseline, proportion, thickness and thinness, circle and plane, realistic rise/ascent, virtual rise/ascent, rhythm and tenet and dignity) concentrate on proportion between curvedness and straightness in performing letterforms and the so-called sixth balance, meaning one-sixth straightness and five-sixths curvedness.

The notion of Savad/سواد (black) and Bayaz/بیاض (blank) refers to the proportion of blackness and blankness and relationship between them in a calligraphy work. Savad and Bayaz refer to a quality in calligraphy, in general, and Nastaliq calligraphy, in particular, that describes a kind of balance between black and white (stuffed and empty spaces created on a page by interrelations between elements on the page) and correlation between positive and negative parts/spaces in the work. Siyah-Mashq/Black Practice, as a popular and distinct compositional style in Nastaliq calligraphy that has different subsets, is an obvious example to explain the notion of Savad and Bayaz (see Figure 12.2).

The descriptive schematic of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING concentrates on graphological features of visual forms, “originally developed for use in forensic analysis of graphic trademarks, or logos, to achieve inter-subjective transparency in legal disputes over possible trademark infringements” (Johannessen, 2013: 156). Johannessen considers shapes beyond their general definition (e.g. A. Dondis, 1973: 44; Arnheim, 1969, 1974; Kress and Van Leeuwen, 1996: 54; Van Leeuwen, 2005: 212). Through the lens of Johannessen’s descriptive schema, “any instance of graphic shape can be analysed satisfactorily with a very small number of variables” that have potential to distinguish meanings (Johannessen, 2013: 7). Crucially for the study of Nastaliq calligraphy, shapes of calligraphic letterforms can be rendered into different fragments that have “potential effects” (Jewitt, 2009) in meaning-making:

Thus, for the porous corpus-based approach to calligraphic letterforms, I apply a brief version of the descriptive schema of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING, first to understand the extent of the functionality of letterforms to make individual distinctive meaning as graphical form beyond language conventions and, second, to understand the extent of correlation between traditional suppositions and recent substantive theories.

The categories of forms in Johannessen’s (2010) model are defined based on SHAPE and ENSHAPENING, in which any region of a given shape can be rendered, or enshapened, in a number of ways.

At the most general level of delicacy, as Johannessen (2010, 2013) explains, the SHAPE system represents the observation that any instance of shape falls into one of two categories: straight or un-straight. In this sense, there can be no instance of shape in the world that is neither straight nor un-straight. Furthermore, no instance of shape can be both straight and un-straight at the same time. Straightness and un-straightness are structurally distinguishable by the number of spatial dimensions. Straightness is regarded as a strictly one-dimensional property of a structure. It specifies only the length of that which is straight and no difference beyond that.

Un-straight, however is a two-dimensional property that specifies a difference beyond length: a curvature or a dihedral angle. Un-straightness is divided into two branches: demarcation, which distinguishes the two different bends of curve and angle, and regional, which is divided into bends of convex and concave (Johannessen, 2013, pp. 160–163). There are four possible choices of un-straightness: un-straight {convex/curve}, {concave/curve} and un-straight {convex/angle}, {concave/angle}.

Shape as a basic element in visual communication is the “line [that] articulate[s] the complexity of shape” (Dondis, 1973: 44). In essence, shape is figures and forms that refer to “the characteristic outline of a plane figure or the surface configuration of a volumetric form” (Ching, cited in Johannessen, 2010. p. 206). Thus, in the configuration of an object, shape is defined by the boundary lines of that object.

In the first step of analysis, the given samples of letterforms are analysed via the SHAPE system. Each given letter is seen as an integrated form, or monolithic form, that must be assessed as a whole. By breaking down any instance of letter in our corpus, two distinct types of line, straight and un-straight, are distinguished. The choices tightly aligned with the un-straight line are curve versus angle and convex versus concave. Figure 12.3 shows how I apply this scheme to letterforms. It shows one instance of 19 individual or single letterforms; I label the features of this letter shape according to the suggested analytical scheme. The letter shape presents four structural variants: straight, un-straight/angular/convex, un-straight/curved/convex and un-straight/curved/concave. The result of SHAPE analysis of 300 images of letterforms is presented in Table 12.1.

By using this synchronic system, I characterise variables between letter shapes, present how these variables distinguish shapes and show how letter shapes make meaning distinctive of conventional meaning. Moreover, particularly by characterising variables, evaluating the traditional theory of circle and plane is accomplished by distinguishing curvedness and angularity and calculating their rate within letterforms.

Average total results of all 300 images in the corpus |

|

Overall results |

|

Straight/Straightness |

16.40% |

Un-Straigt/Un-Straightness |

83.46% |

Results in more detail |

|

Straight/Straightness |

16.40% |

Curve/Curvedness |

55.25% |

Angle/Angularity |

28.21% |

SHAPE Variables |

|

Un-Straight/Curve/Convex |

34.52% |

Un-Straight/Curve/Concave |

29.40% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Convex |

21.39% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Concave |

14.66% |

As shown in Table 12.1, the rate of diversity and similarity between shapes in letterforms is indicated by different variables described in the SHAPE system. Table 12.1 shows the use of un-straight lines at a rate of 83.46 per cent, which is greater than for straight lines at 16.40 per cent. The table also shows that from the un-straight lines, curved lines appear at a higher rate than angularity, with a rate of 28.21 per cent within un-straight bends. This indicates that the calligraphic letterforms in our corpus are prone to un-straightness and curvedness rather than straightness.

At a higher level of delicacy, Table 12.1 shows four patterns, or variables, used in the shapes of letterforms. Accordingly, the largest structural occurrence used is ‘un-straight/curve/convex’ at 34.52 per cent and the smallest is ‘un-straight/angle/concave’ at 14.66 per cent. The rates of these four structural occurrences do not show a substantial difference. This level of delicacy can be meaningful in that the complexity or simplicity of each form can be illustrated.

Particularly with regard to letterforms in the corpus, the variant in use in the four defined structural patterns, combined with no significant difference between their amount/percentages, represents the equal use of these four structural models in Nastaliq letter shapes. In essence, it shows variegation in the use of different structural occurrences in letterforms and Nastaliq calligraphy as a whole. Here, we do not attend to the indicated complexity or density of each letterform by analysing the extent to which each given shape is complex or simple according to the number of structural variables used. Instead, we apply this synchronic scheme to the letterforms, first, to understand the extent of compatibility with the scheme used for graphic forms and, second, to enumerate the amount of curvedness and straightness in letter shapes and sequentially examine the traditional theory of circle and plane for authenticity and the extent of analogousness with the shape articulation in the graphic landscape.

ENSHAPENING describes shape based on the relationship between figure and ground. Shape in relation to figure is defined by positive shape and negative shape. Thus, if a shape pertains to a figure, it is a positive shape, and if it pertains to the ground, it is a negative shape (Johannessen, 2013: 164).

If the figure (of the letter or graphical element) is composed of a multiregional figure, is a compound shape, but pertains to only one region or a mono-regional figure, it is a conjoined shape. In addition to these four types of shapes, two more are defined based on the relationship between figure and ground. If the relationship of figure-ground only demarcates the two regions of figure and ground, then it is a massive shape, but if this relationship makes three regions of figure, interior ground and exterior ground, it is a contour shape (Johannessen, 2013: 166).

To define something as graphic phenomena or visual forms as graphic forms, as Johannessen suggests, we cannot neglect Gestalt theories. According to these theories, a necessary characteristic of every graphic phenomenon is that “it demarcates an expanse into at least two distinct regions” of figure and ground (Gestalt in Johannessen, 2013: 163). In essence, to account for something as a graphical form, we must define it in relation to the space or region in which the given form is visible. This space is called the ground and is identified in a two-dimensional system in which two planes are meaningful. In essence, a graphic phenomenon is formed in a two-dimensional system in which only two planes are presented.

Thus, to evaluate calligraphic letterforms through relevant graphical theories, to put them in the category of graphic forms (i.e. to adopt letterforms as graphic forms), we need to describe them in terms of a figure–ground relationship. In addition to the SHAPE system, which distinguishes bends and straights, we need to parse letterforms through a system that presents the relationship between ground and figure in a graphical structure. As explained earlier, ENSHAPENING describes three simultaneous choices that are based on the relationship between figure and ground (Johannessen, 2010, 2013).

The result of ENSHAPENING analysis of 300 images of letterforms is presented in Table 12.2. Table 12.2 shows that all figure types are presented as positive; having no negative figure in our samples means that in Nastaliq calligraphy basically all letter shapes in terms of their relationship with ground pertain to the figure and not the ground.

The corpus reveals a significant tendency (60.25 per cent) towards the conjoined structure of positive/conjoined/massive, showing letterforms using a mono-regional figure such as in Figure 12.4a; 16.52 per cent of the letterforms are prone to the compounded type made up of multiple regions (Figure 12.4b). With regard to the ground complexity, the corpus indicates that 18.91 per cent of the letterforms is prone to choose positive/conjoined/contour; see Figure 12.4c, in which a bounded shape in the upper-right section creates three regions of figure, interior ground and exterior ground, and only 4.28 per cent of the samples represents a positive/compounded/contour structure, or outline shape, demarcating three regions of figure, interior ground and exterior ground (Figure 12.4d).

Average total results of all 300 images in the corpus |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

60.25% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

18.91% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

16.52% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

4.28% |

Despite the high level of dynamism in handwritten Nastaliq scripts, ENSHAPENING is also descriptively adequate to characterise the figures. In essence, figure-type discussion in the descriptive scheme of ENSHAPENING is also adequate for discussion of Savad and Bayaz/blackness and blankness (سواد و بیاض) in Nastaliq calligraphy. This discussion highlights the balance between the dark spaces filled by ink (i.e. figure of the letterforms) and the empty (probably white) blank spaces created between them. Coordination between black figures and blank space is itself considered a figure that pertains to the ground (negative figure; Figure 12.5). Although in different implementational styles in Nastaliq, especially in Siyah-Mashq/black practice7 scripts, we find negative figures, created by juxtaposing different black traces so that blank traces become meaningful and are presented as lying in front of the black figures, the corpus only specifies four choices in a positive type of figure (see Figure 12.6).

One might argue that ENSHAPENING cannot describe Nastaliq letterforms, especially when we figure complexity to distinguish between conjoined and compounded shapes among dotted letterforms or letters with strokes. The use of strokes and dots in some letters is important in classification of figure types. For example, in Figure 12.7, one can count the dotted letter shape as a compounded shape, while by excluding dots it can be considered a conjoined shape. Thus, to leave behind such problematic issues, I examine dotted letters in the corpus by both including and excluding dots.

Another problematic point which may arise in description of letterforms through ENSHAPENING concerns letters that have lashes tilted, as in Figure 12.4b. Sometimes, especially in handwritten calligraphic scripts, we face different conditions in which strokes stick to the main figure of the letter or are detached from the main body of the letter. However, although some flaws exist in SHAPE and ENSHAPENING in confronting the high level of dynamism in Nastaliq letterforms, this synchronic scheme can be applied to calligraphic letter shapes as “what we generally refer to as graphic …” (Johannessen, 2013: 16). In addition, the specific concept of Savad/سواد (black) and Bayaz/بیاض (blank) in Nastaliq in particular can be explained through ENSHAPENING and particularly related to its concepts of positive shape and negative shape. Also, the theory of circle and plane (i.e. proportion between curved bends and straight lines in Nastaliq) can be described by using the SHAPE system and authenticates the notion that the proportion of circles in Nastaliq is greater than straightness, at a 5:1 ratio.

As mentioned earlier, to examine letterforms through the synchronic schema of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING, we need a general system that examines all aspects of Nastaliq letter-shapes and considers the dynamism existing in calligraphy as well. Moreover, to compare calligraphic letterforms with graphical forms and realising how a letterform functions like a graphical form, and then to describe the process in which a calligraphic letterform makes a communicative visual event, we need to consider circumstances under which a calligraphic practice has been followed. In other words, to describe visual letterforms, we need to describe the particular situation or conventional way in which letterforms are shaped and presented. Thus, a framework that encompasses all conventions and traditions is required. A scheme is needed that explains the dynamic process of a link between conventions and material substance through which “meaning potentials” are made in calligraphic letterforms (Johannessen, 2010: 117).

Using the theory of graphetics articulation borrowed from Johannessen (2010), we can explain a dynamic process in which the three factors of ‘body’, ‘tools’ and ‘substance’ play the main role to create a communicative visual event in Nastaliq. During this process, a human bodily acts using tools over substance to perform a communication process (Johannessen, 2010: 122). In essence, in such a process, new forms are shaped that lead to new meanings and finally create an integrative communicative event. This process of meaning-making revolves around the notion of articulation, which “refers to the process by which a given meaning potential finds a form” (2010: 121). In this process, a graphic work or artefact is produced so that an uncountable set of acts—constrained by efficiencies and limitations of the human body and tools—is assigned.

Based on the theory of articulation, Johannessen suggests a dynamic analysis method of “articulatory graphetics”, which is comparable to “articulatory phonetics”, applicable to graphic forms to understand the differences in various visual communicative events that they cause and to identify factors that create similarities and differences in communicative events created by graphic trademarks. However, understanding communicational events in Nastaliq calligraphic letterforms, using graphetics articulation, which characterises a general set of principles and conventions that apply in all graphic signifiers, leads us to understand the relationships of letterforms and their role in the meaning-making process and subsequent making of communicational events. Moreover, applying such framework over calligraphic letterforms allows us to identify and characterise traditional principles of Nastaliq. We can then characterise conventions which are bound in material, tools and acting and propose a calligraphic articulation.

The abstract process of articulation applied to calligraphic letterforms is defined within the three main factors of body, tools and substance. In this way, the calligrapher’s body practises using tools on material substance, resulting in a calligraphic event and making a communicative difference in perceivers’ eyes. The three main factors of body, tools and substance, which must be considered in analysing calligraphic letterform, are called “sources of affordance”8 as they facilitate interaction between our biological system and the environment. Thus, the three factors of body, tools and substance are the resources that influence our biological system and eventually “influence the potential for expressing meaning” (Johannessen, 2010: 122).

However, drawing a comprehensive articulation particularly for Nastaliq calligraphy—or a calligraphic articulation—requires attention to all three factors of affordance and traditional and conventional rules of Nastaliq calligraphy, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Moreover, to propose a self-inclusive calligraphic articulation, or framework that can explain communicative processes by which meaning potentials find form in letterforms, we must also consider the process of perception.

Therefore, we confine our discussion to a brief account of one general convention of graphic signifiers, enumerated in articulatory graphetics by Johannessen (2010), created by the body as the constant factor of affordance in articulatory graphetics. That is, we employ a concise version of the articulatory graphetics to describe communicative events articulated in calligraphic letterforms within different levels and in relation to the three factors of affordance of ‘body’, ‘tools’ and ‘substance’.

Thus, the chapter can be considered a daring step to see calligraphy from a new perspective, not just as an abstract art.

According to Johannessen, in relation to the body, we must remember three important points. First, we must determine the scope of the body in relation to calligraphy; this means determining what parts of the body and organs are used and involved in the process of performing a specific type of calligraphy, Nastaliq. This is not a biological discussion of the human body to explain how its processes work independently or together but, rather, to understand what they do in the implementation of calligraphy and, for example, what part of the hand is employed in writing. The second point involves how we employ our organs to perform a letterform and “what […] we do with […] the body’s affordance, rather than the body in itself” (Johannessen, 2010: 123). In short, graphetic articulation is concerned more with doing than being. For instance, performing letter ب (i.e. NAME: be, IPA:[b]; Figure 12.8) requires specific hand movements and, indeed, particular parts of the hand must be used because “a specific kind of bodily action results in a specific kind of line” (Johannessen, 2010: 123).

In letter ب [b], specific movement of the wrist from right to left and slight motions of the thumb and index finger lead to a certain type of line (Figure 12.8). During tracing, the number of times we take our hand off the paper, the number of movements usually involved in writing the letterform and the number of times we pick up ink or renew the ink in our pen are related to the body acting and included in the process of performance. Figure 12.8 shows that the process consists of three separate hand movements. Over time, this set of hand movements, the result of rehearsing by the calligrapher, creates a certain type of activity and thus imposes a set of norms and conventions in performing letters. Although this set of conventions is defined in a specific social and cultural context, it is basically generated in the body acting and general organic efficiencies of the human body. In other words, although social and cultural aspects (e.g. Persian system of writing, traditional methods of using tools, life style, people’s attitude) influenced the establishing structure of calligraphy, the general organic system of the body imposes itself to ordain specific movements and accordingly generates special conventions. In fact, we cannot act beyond the limitations imposed by the organic system of the body. These restrictions, forced by certain body movements, thus result in particular types of lines and shapes.

In addition to performing and working with tools on a material substance (e.g. pen on paper), in Nastaliq calligraphy, preparation of tools and materials also needs an acting body. For example, trimming a reed pen and preparing paper and ink, particularly in traditional methods, require specific body acts. Therefore, because of the affordance of the body even in preparation of tools and material substance, we can consider it a source of affordance which is constantly at work even in other sources of affordance in calligraphic articulation (i.e. tools and substance). Overall, the crucial role of the body in the generation of principles and conventions, whether related to performance or tools and substance, laid down in performance is evident (Figures 12.9 and 12.10). According to Johannessen (2010), “we must keep in mind that regardless of culture there is at least one constant in the genesis of such convention: the human anatomy” (Johannessen, 2010: 124).

In Nastaliq calligraphy, especially in the traditional manner, the calligrapher prepares a reed pen, ink and paper manually, according to specific principles. The process of preparation entails a specific type of body act and subsequently results in a specific set of conventions regarding tools and substance. Apart from these, choosing specific types of instruments and materials in Nastaliq calligraphy (that have cultural roots) imposes limitations on body activities as well. In other words, the body and tools and material substance are in a two-way interaction and simultaneously influence each other in creating conventions over time. Holding the cutter, measuring cutting points, adjusting the angle, carving around sides and cutting the broad edge of the pen put the body in a specific position to act, and the body imposes its own limitations based on its organic system.

Another point regarding the body and its interaction with the other two sources of affordance is that not only does the human anatomy as a constant factor influence the establishing principles and conventions, but the tools, materials and substance also play roles in generating conventions. For instance, to implement a particular letterform or specific type of compositional form, we must act in a specific manner. Moreover, using a specific given size of pen also requires acting with a specific hand movement/certain range of hand motions. For example, if the calligrapher, according to the piece he/she wishes to perform, chooses a large pen (a so-called epigraphic pen) to write a large epigraph, the scope of hand movement is more extensive (expanded from wrist to arms and even shoulders and torso) than when he or she is writing with a small pen, limiting movement to the fingers.

Here, we focus on the body as a constant factor of affordance which influences the other two factors and causes conventions in implementation of graphic signifiers and calligraphic letterforms.

According to Johannessen (2010), human anatomy is considered a constant factor in articulatory graphetics: “Human biology is a crucial component in the genesis of graphic convention” (p. 124). Therefore, human anatomy affects the motion of the body (acting body) in performance and subsequently imposes a set of principles and conventions. The set of restrictions and conventions the body creates in relation to performing lines, shapes and letterforms and the tools and material substance are enumerated as general points that apply in all forms of graphic signifiers. Here I explain one of these conventions and discuss it as specifically related to Nastaliq calligraphy.

As Johannessen mentioned, the first general conventions that the body causes is a “general consensus that our anatomy favours curved motion when we manually trace graphic lines, whereas straight lines take considerably more control and effort” (Johannessen, 2010: 124). In this respect, although performing all letterforms requires ultimate precision and control in the hands, generally letterforms tend to use curved motions. This is demonstrated by the analysis of letterforms based on the SHAPE system, showing the shape variables so that curved lines appear at a higher rate of use than straight lines. This indicates that Nastaliq letterforms are more prone to curved motion than straightness (see Tables 12.1 and 12.2 and Appendices 1–2).

This also demonstrates the traditional notion in the implementation of Nastaliq that the circle is the dominant shape in heterogeneous letter shapes so that the ratio of circles to straightness is always 5:1 (see the circle and plane theory). This can also be used as affirmation that Nastaliq letterforms are designed based on anatomical tendencies of the human body. According to the practical theories of implementation, tracing a circle is difficult and more complex than tracing a plane, so performing circular Nastaliq letterforms requires very deliberate and precise attention in accordance with specific rules and principles. For this reason, training in performance of circular calligraphic forms is a main element of calligraphy education. As Baba-Shah Isfahani (1587 in Ghelich Khani, 2012) said, the acme of beauty and the skill of the calligrapher are displayed in the circles he/she performs. Thus, hand control should be greater when performing a circle than a plane.

In addition to the considerable number of circles and circular forms in Nastaliq, which show that the letterforms are generated based on ergonomic factors of the human body and all letterforms generally favour curved motions, we must mention the 12 thetical traditional principles9 of this type of calligraphy in which a separate principle is specifically dedicated to the circle. This principle, which is seventh in a set of 12 series of rules, defines circular and rounded motions in letterforms and specifies regulations and conventions in tracing circles. In 1587 Baba-Shah Isfahani (cited in Ghelich Khani, 2012) defined a statute for training in Nastaliq; the circle or rounded form is defined as a form that must evoke or convey a sense of softness, wit, naturality and elegance in the viewer, for example, through the extensive forms of letters and circular letters (Figures 12.11 and 12.12). As a result, the many notions of curvedness and circles in Nastaliq show an affinity for or proximity to this type of calligraphy and the nature of the human body.

Another point regarding the curve is that the circle has a long history and important reputation in Iranian culture and mysticism. In this respect, some gnostic sects, such as the Nuqtavi and Hurufi movements, have been formed on the concept of the circle and curved motions. Sufi whirling and the use of circles in Islamic and Iranian architecture (e.g. domes, arches) reflect the central role of the circle in Persian traditional representational culture. Some old manuscripts mention that the basis generation of calligraphy is the dot, and this dot is derived from the circle, thus Baba Shah Isfahani, in 1587, Sultan Ali Mashhadi, in 1453–1520 and Ibn Muqla Shirazi, in 885–940 (cf. Ghelich Khani, 2012; Shahroudi, 2008; Ernst, 1992; Shafiee, 1950; Soroush, 1950).

This means that the calligraphy is based on the circle; as mentioned in the theory of the circle and plane, every heterogeneous letterform is fitted in a circle. We do not intend to examine Nastaliq based on cultural and historical background, but it is appropriate to say that cultural and social conventions can also be related to or originate from the body and conventions imposed by it.

Several aspects in Nastaliq indicate the first general convention in graphic signifiers: the tendency of the body to use curved motions when tracing lines. For instance, another important point in the set of principles in Nastaliq calligraphy is ‘composition’, which is first among its 12 principles. ‘Composition’ in this set of rules is divided into ‘partial’ and ‘total’. ‘Partial composition’ refers to the rules and regulations in combining letters, while ‘total or overall composition’ implies the compositional style and a set of rules and conventions regarding juxtaposition of letters to make an integrated row line. The second part of this principle can potentially refer to the body’s tendency towards curved movements. Based on this principle, a row line in Nastaliq calligraphy should be oriented upwards (or have an upwards trend); in this meaning, the row line moves to make a curved line at the end. One rule is that the first and last characters (letterforms) of a row line should be placed slightly higher than the rest of the letterforms. Thus, a row line that includes different characters and letters should ultimately appear as an integrated curved line that trends upwards. This convention in Nastaliq recalls a clockwise motion, from the top to the right and then down to the left. This is also analogous to the direction of the hand in the Persian writing system, moving from right to left (Figure 12.13).

Another norm or principle of Nastaliq calligraphy is the second rule in this set, the ‘baseline’. This defines or specifies the set of conventions and rules about horizontal lines over which the letters are placed. All conventions and principles related to the baseline also compose rows of letters to form an integrated curved line so that the whole line appears as a curved line moving in a clockwise circle (Figure 12.13).

Another point regarding the first general convention Johannessen suggests (the tendency of the human body towards curvedness) is that in Nastaliq calligraphy, because of its high level of dynamism, there is no absolutely straight line, or at least no plane is shaped only by straight lines. In this respect, the role of the human body, which favours curved and non-straight lines, in shaping such calligraphy is obvious.

In this respect, we also mention the principles of plane, circle, virtual ascent and virtual descent (Figure 12.14). All four principles concern the motion of hand and pen, such that a non-straight line results. For instance, a circle is created by curved motions of the hand so that when the viewer sees it he or she will perceive a sense of movement and action. ‘Virtual ascent’ and ‘virtual descent’ occur when the hand moves from below to above and, conversely, when it moves from top down but not in a straight line (see Figures 12.14 and 12.15).

Both principles emphasise indirect movement when descent and ascent occur. This implicitly indicates that the human body and hand have more control and the performer has a high level of skill; tracing an absolute straight line is impossible, so according to traditional calligraphers there cannot be symmetry or analogy between the same letterforms performed by the same calligrapher at different times. Even though a performer is skilful and fluent with maximum control of the hand, performing the same letters so that they seem to be mirror images of each other is impossible.

In his proposed theory of articulatory graphetics, Johannessen (2010) suggests that a graphic signifier can be analysed on different levels. This means, for example, that each graphic form (e.g. logo, letterform) is rendered in different levels (stages) which are based on “multiple time scales” (p. 131). According to Lemke, quoted by Johannessen (2010), a communicative event is articulated in “multiple time scales” which are defined by different micro events (Johannessen, 2010, pp. 131–141). In essence, a letterform as an event occurs in a time scale which is itself divided into several time scales. This integrative communicative event can be broken down into multiple events or several micro events, each of which occurs in a range of time. Lemke (2015) defines three levels of analysis: macro, meso and micro. The macro level, L + 1, is generally considered a higher level and often covers a longer time scale; especially for calligraphic letterforms, a combination of letterforms (like a word) caused through juxtaposing of at least two letterforms can be analysed at the macro level, L + 1. A meso level, L, is used to analyse the object of inquiry, here letterforms. The micro level, ‘L − 1’, which is understood as a lower level of analysis, focusses on tiny segments of the letterforms.

Therefore, to analyse the process of making a letterform, we must analyse different constitutive events that occur within different intervals or time spans. According to Johannessen (2010), the process of performance begins “at some points in time” and “at a later time it ends” (p. 131). In this meaning, a communicative event is articulated in a range of time in which there are two points of start and end (Figure 12.16).

The figure defines a generic view of the performance process and defines a range of time in which two points mark the beginning and end. This is a broad view of the performance process; it is called level L, meaning, for example, that in an extensive form of the letter ب [b], the letterform begins from point 1—at a point in time—then after passing a range of time which may last from seconds to minutes, it will end at point 2 (Figure 12.16). In level L, we limit the process of tracing between times 1 and 2; there are, of course, smaller ranges of time and thus several micro events can be analysed at lower levels.

According to Johannessen, the level at which we divide a communicative event in the performance process into different sub-events, which are themselves limited in different smaller ranges of time from seconds to hours or days, is called level L − 1 (Figure 12.17). In applying level L − 1 analysis to calligraphic letterforms, we consider every hand movement, or every time the hand leaves the paper, as a sub-event. For instance, in level L − 1, we define at least three events which happen in different ranges of time. In this level of analysis, as defined in Figure 12.17 based on the number of times the hand is taken from the paper or on the number of ink replenishments, we have at least three sub-events.

However, in addition to the number of hand movements in level L − 1, we can also separately apply level L − 1 to analyse letterforms based on using pen and ink. In other words, in addition to the body motion that is influential in creating events and sub-events, we can analyse a letterform with the centrality of substance (ink) and tool (reed pen) and distinguish different sub-events and micro events created in the process of performance. For example, in Figure 12.18, the extensive form of the letters (considered an event, in level L), we see that the number of sub-events varies according to the number of ink replenishments and thus the removing of the hand from the paper. In addition to traditional general principles of Nastaliq that determine an approximate number of hand movements to perform each letter, the quality of tools and the substance also affect the rate of sub-events in a letterform.

For example, as the density of ink or paper roughness grows, the number of ink replenishments, and therefore, the numbers of sub-events increases. For tools and their use, an analysis based on the defined level is more complicated. In analysing letterforms based on use of the pen, distinguishing sub-events is complex, as in each sub-event we must recognise or segregate different small events/micro events which have made a specific part of the reed pen based on various parts of the broad-edged reed pen, as specified in traditional calligraphic principles of Nastaliq. For instance, each part of the pen, including the tip or apex (also called the sting), the nib and other divisions of the edge (1/3, 2/3 or 3/3) are used for tracing different parts of a letterform (Figure 12.19).

In forming each letterform like the letter ب [b], as an integrated overall event, different parts of the pen from the tip and nib (3/3) are used to fulfil one part of the event; in other words, each part of the pen creates a sub-event. Thus, numbering these sub-events requires numbering or distinguishing thickness changes during the performance of the letterform. Of course, in this process, the body is also involved as using different parts of the broad edge requires changing the angle of the tool over the paper through hand movement.

Another point to mention is the nuance of darkness and light in the duration of a letterform as an integrated event, which causes several micro events in each sub-event by different extents of pressure over the pen from the hand. In essence, changing the pressure of the hand by pen over paper and indeed over substance (i.e. ink) leads to micro-events that themselves comprise many other tiny events. Figure 12.20 shows that an event comprising several tiny events is produced by different hand pressures and different densities of ink over substance, which makes an overall event with a specific texture from dark to light or vice versa. This overall textural event with black-and-white nuance comprises several micro-events which can be understood in a lower level (Figure 12.20). Considering that no explicit border exists between micro events, we can move beyond these levels of analysis so that each micro event can be considered a distinct event that itself is divided into several other tiny events, which are analysed at lower levels. Each tiny event also encompasses other subordinated events occurring in different scales of time.

This discussion recalls the theory of multimodality in which different modal resources are articulated to make an overall integrative and meaningful text. This is analogous to a communicative event in which several micro events occur in a range of time in collaboration to produce an integrative multimodal form or event. In this respect, the process of performance is considered a multimodal process that results in a multimodal communicative event.

Thus, a specific tool and substance generate specific conventions that result in different communicative events. Particularly in Nastaliq, a set of principles used in performance is generated by relying on specific characteristics of the reed pen, ink and paper that cause specific events different from other types of communicative events. Another point is that although the manner of analysis Johannessen suggests relies on graphetics articulation applied to the calligraphic letterforms of Nastaliq, we still cannot limit letterforms in the proposed levels in graphic signifiers. Considering the central role of the human body in such type of calligraphy and the high level of dynamism and fluidity in letterforms, distinguishing different events and micro-traces and separating them is difficult.

Accordingly, in addition to the central and constant role of the body in the whole process, it is also always in a collaboration with the other two factors of affordance, namely, tools and substance. This means that in analysing a letterform based on the suggested levels, we cannot separate the body acting, the substance and the tools, as we cannot specifically attribute a convention (in Nastaliq performance) to only one of the three factors. In essence, calligraphic articulation is based on the three agents of affordance that work together in making communicative events.

The chapter represents a significant step towards a greater goal, as drawing specific articulation for calligraphy requires that all aspects be considered and all traditional conventions scrutinised. Thus, this chapter has completed only one stage of this lengthy process.

Based on the synchronic system of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING and using a brief version of the theory of articulatory graphetics (Johannessen, 2010), I argue that calligraphy as a multimodal text is a distinct semiotic mode and a means of communication that has its own autonomous meaning regardless of the lexical and conventional meanings of the language. In this sense, calligraphic letterforms function as modal resources in their own right. Based on Johannessen’s theory of articulatory graphetics, I suggest that Nastaliq letterforms potentially function as graphic signifiers, overlapping with the general graphic conventions described in the theory of graphetic articulation. Like graphic signifiers, the configurations of Nastaliq letterforms are enacted based on the graphic principles generated by human anatomy. Accordingly, principles and conventions applicable in graphic signifiers potentially lead to traditional conventions of calligraphy that are close to handwriting scripts.

To understand the extent of calligraphic letterforms’ independence from conventions in language, in the first section, the chapter demonstrates how a corpus-based study of calligraphic letterforms can be conducted by using a descriptive scheme—for graphic forms—with the two systems of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING. The article shows that structural occurrences defined in SHAPE and ENSHAPENING are nested in letterforms and subsequently are in concert with features defined in the traditional notion of circle and plane in Nastaliq. The compatibility between this theory and the features defined in the SHAPE and ENSHAPENING systems as descriptive schema for graphic forms indicate a connection between traditional principles in Nastaliq implementation and universal features of graphics. In other words, traditional conventional rules in implementation of this calligraphy lead to a general set of principles in graphics. Applying these schemes to the corpus authenticates the theory of circle and plane in Nastaliq by indicating that most of the lines forming shapes in letters are un-straight and curved, and only a small proportion is straight. The corpus also indicates that the ratio of bends to straights is approximately 5:1, as claimed in the traditional theory of circle and plane.

The corpus also demonstrates that four SHAPE variables used in letterforms are distributed approximately at equal rates, presenting variation in the use of structural occurrences in Nastaliq calligraphy. In other words, four SHAPE patterns defined within un-straight lines (Un-Straight/Curve/Convex, Un-Straight/Curve/Concave, Un-Straight/Angle/Convex, Un-Straight/Angle/Concave) are almost evenly distributed in Nastaliq letter shapes. All four variables defined in the SHAPE system are recognised in letterforms in the corpus.

In the ENSHAPENING system, all samples in our corpus are characterised as a positive shape; 60.25 per cent of letterforms falls into the category of Positive/Conjoined/Massive. In terms of complexity of figure and ground, most of the samples are conjoined and massive, while only a small number has a compounded contoured shape. As a result, although the schema of SHAPE and ENSHAPENING is not accountable in describing calligraphic forms because of the high level of dynamism and delicacy in Nastaliq, both systems are consistent with the fractals derived from calligraphic letterforms of Nastaliq.

In the second part, I consider calligraphic practices from the perspective of graphetics and examine conventions through the three aspects of acting body, tools and substance in articulated graphetics. Within the set of traditional principles of Nastaliq, I determine the traces of graphic conventions which are at work in the process of calligraphic performance.

Principles within the set of 12 traditional principles in Nastaliq, which are considered doctrine in Nastaliq calligraphy, are analysed for general conventions defined in graphetics articulation. For example, the first general conventions in the graphetic articulation graphic (i.e. tendency of body towards curved motions) manifest in traditional principles of Nastaliq and these principles refer to the human body.

The results achieved through using the theory of articulation are as follows: (1) All principles defined in traditional system of Nastaliq calligraphy, whether in implementation or preparation of tools and substance, are directly or indirectly related to the body and under the effects of the human body. (2) Some conventions are tied to the system of writing in the Persian language and Iranian cultural aspects (like mysticism). (3) We cannot separate the three factors of affordance from each other; they complement each other while interacting to create communicative events. Accordingly, this chapter supports the assumptions that affiliate Nastaliq letterforms as autonomous graphic forms, interpersonally meaningful in their own structure. Consequently, they are adequate with conventions in graphic phenomena, thus supporting the hypothesis that calligraphic letterforms are analogous to a general universal set of graphic features. The findings also corroborate the authenticity of the traditional notion of circle and plane in Nastaliq calligraphy; furthermore, the study demonstrates compatibility between traditional principles of Nastaliq and general principles in graphics.

However, considering the complexity, dynamism and delicacy of Nastaliq scripts, I fully understand that this paper covers only a small part of this territory and captures only a teeny part of the broad outline of this intricate and interesting field. Of course, to draw a pervasive articulation and suggest a grammar for calligraphy, all traditional principles in calligraphic performance must be scrutinised within all factors of affordance; moreover, to suggest a grammatical system, additional research is needed to characterise distinctive features of Nastaliq by investigating semiotic aspects of Nastaliq calligraphy.

1Mode as a fundamental concept in the theory of multimodal social semiotics is the result of cultural formation of a material. Each mode has its own specificities and categories comprising different semiotic resources and each has “differential potential effects” for meaning-making (Jewitt, 2009). For example, gesture as a mode has many semiotic resources, such as amount of stretching movement in space, highness and lowness of sound and the path of the eyes; all are categories that make up a semiotic resource of meaning-making in the mode of gesture.

2Individual letterform suggests a form of letter used or written alone without any conjunction to any letterform, although in juxtaposition with other letterforms on a row/line.

3Extensive letterform refers to the second face of letters in Nastaliq, in which letters are written in a stretched form.

4Second letterform suggests the secondary face of a given letter that is never written individually but always in conjunction with at least one letter.

5A compound form in Nastaliq calligraphy suggests a combination of at least two second letterforms (secondary face of two letters).

6Compositional rules in Nastaliq calligraphy: Suggest a set of principles to compose calligraphic letterforms in two phases of ‘partial composition’ and ‘overall composition’. Partial composition refers to regulations in combining letterforms and the interconnections of calligraphic elements (from letters to ornamental elements) in general, while ‘overall composition’ refers to rules and conventions in juxtaposing calligraphic letterforms on the baseline and the ways of laying out rows and framing them in the page.

7Siyah-Mashq/Black practice is a popular compositional form in Nastaliq with different sub-sets that are based on various factors such as calligrapher purpose and audience. In the Qajar era (1785–1925), great calligraphers such as Mir-Hossein Khoshnevis, Mirza-Kazem-Tehrani and Mirza Gholamreza Isfahani emerged. Siyah-Mashq has been characterised as a distinct style of writing in Nastaliq calligraphy (see Figure 12.13).

8Johannessen refers to the definition of affordance from Gibson’s (1989[1979]) ecological perspective. In this view, affordance is “something which the environment imposes on the biological system” (Johannessen, 2010, p. 122). In his theory of visual perception, Gibson (as cited in Johannessen, 2010) explains affordance as the way by which a biological system like the body interacts with the environment.

9The 12 main thetical traditional principles in Nastaliq calligraphy are (1) composition (partial and total), (2) baseline, (3) proportion (circle to plane, thinness to thickness, distance between letters and from baseline, rhythm in a line), (4) weakness, (5) thinness, (6) plane, (7) circle, (8) virtual ascent, (9) virtual descent, (10) rhythm, (11) beauty and concinnity and (12) dignity.

Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual Thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and Visual Perception: The Physiology of the Creative Eye. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Barat zadeh, L. (2006). خوشنویسی در ایران, Tehran.

Bayani, M. (1984). احوال و آثار خوشنویسان (Ḵošnevīsān, Calligraphers). Tehran.

Bayani, M. (1984). “خط فارسی”(Persian Calligraphy). Tehran.

Bolkhari, H. (2006). “وحدت وجود و وحدت شهود:مبانی عرفانی هنر و معماری” (Spiritual Foundations of Art and Architecture: Pantheism and Unity of Intuition). Tehran.

Dondis, D. A. (1973). A Primer of Visual Literacy. Cambridge, Ma: MIT Press.

Eghbal, A. (1990). در ایران” “شعر و موسیقی (Poetry and Music in Iran). Tehran.

Ernst, C. W (1992). The spirit of Islamic calligraphy: Bābā Shāh Iṣfahānī’s Ādāb al-mashq. American Oriental Society, 112(2). www.jstor.org/stable/603706.

Falsafi, A. (2000). “بررسی و شناخت کشیده ها در خط نستعلیق”(Exploring and Understanding expanded lines in Nastaliq Calligraphy). Tehran.

Ghazi Monshi, A. (1988).”گلستان هنر” Tehran.

Ghelich Khani, H. (1993). “رسالاتی در خوشنویسی و هنرهای وابسته”. Tehran.

Ghelich Khani, H. (1994). “فرهنگ واژگان و اصطلاحات خوشنویسی و هنرهای وابسته”, Tehran.

Ghelich Khani, H. (2012). Adab al-mashq (Manners of Practice). Tehran.

Gibson, J. (1989)[1979]. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Irani, A. (1983). “پیدایش خط و خطاطان”. Tehran.

Jewitt, C. (2009). The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp. 14–27). London: Routledge.

Johannessen, C. M. (2010). Forensic Analysis of Graphic Trademarks: A Multimodal Social Semiotic Approach. PhD. Thesis, Department of Language and Communication, Odense.

Johannessen, C. M. (2013). A corpus-based approach to Danish toilet signs. RASK—International Journal of Language and Communication, 39, 149–183.

Kress, G., and Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading Images - The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

Lemke, J. (2015). Interview With Jay Lemke. In T. H. Andersen, M. Boeriis, E. Maagerø, and E. Seip Tønnessen (Eds.), Social Semiotics. Key Figures, New Directions (pp. 114–140). London: Routledge.

Ormavi, S. (2006). “الرساله اشرفیه فی النسب التالیفیه، ترجمه بابک خضرائی”. Tehran.

Shafiee, M. (1950). Adab al-mashq (Manners of Practice). Baba Shah Isfahani, Tehran.

Shahroudi, F. (2008). پیدایش و تحول خوشنویسی در ایران (The Emergence and Development of Calligraphy in Iran). Tehran.

Soroush, K.(1950). Adab al-mashq treatise (Manners of Practice), A ballad by Mir Emad al-Hassani, Tehran.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Typographic meaning. Visual Communication, 4(2), 139–155.

Detail of the result of SHAPE analysis of 300 images of letterforms

19 Individual letterforms + Dot + 4 Extensive forms |

|

Overall results |

|

Straight/Straightness |

16.31 % |

Un-Straight/Un-Straightness |

83.68% |

Results in more detail |

|

Straight/Straightness |

16.31% |

Curve/Curvedness |

60.66% |

Angle/Angularity |

23.01% |

SHAPE Variables |

|

Un-Straight/Curve/Convex |

33.89% |

Un-Straight/Curve/Concave |

27.68% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Convex |

29.94% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Concave |

8.47% |

18 Second letterforms/Sole letterforms |

|

Overall results |

|

Straight/Straightness |

18.83% |

Un-Straigt/Un-Straightness |

81.16% |

Results in more detail |

|

Straight/Straightness |

18.83% |

Curve/Curvedness |

57.79% |

Angle/Angularity |

23.37% |

SHAPE Variables |

|

Un-Straight/Curve/Convex |

37.08% |

Un-Straight/Curve/Concave |

31.12% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Convex |

21.84% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Concave |

9.93% |

15 Compound Forms Based on Principles of Implementation |

|

Overall results |

|

Straight/Straightness |

13.69% |

Un-Straight/Un-Straightness |

86.29% |

Results in more detail |

|

Straight/Straightness |

13.69% |

Curve/Curvedness |

50.85% |

Angle/Angularity |

35.44% |

SHAPE Variables |

|

Un-Straight/Curve/Convex |

32.62% |

Un-Straight/Curve/Concave |

34.75% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Convex |

19.25% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Concave |

13.36% |

15 Compound Forms Regardless of Principles of Implementation |

|

Overall results |

|

Straight/Straightness |

17.56% |

Un-Straight/Un-Straightness |

82.423% |

Results in more detail |

|

Straight/Straightness |

17.56% |

Curve/Curvedness |

50.45% |

Angle/Angularity |

31.98% |

SHAPE Variables |

|

Un-Straight/Curve/Convex |

31.46% |

Un-Straight/Curve/Concave |

23.70% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Convex |

22.84% |

Un-Straight/Angle/Concave |

21.98% |

Detail of the result of ENSHAPENING analysis of 300 images of letterforms

19 Individual Letterforms + Dot + 4 Extensive Forms |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

66.66% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

6.66% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

23.33% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

3.33% |

18 Second Letterforms/Sole Letterforms |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

65.21% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

8.69% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

26.08% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

0.0% |

15 Compound Forms Based on Principles of Implementation |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

73.06% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

12.50% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

10.56% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

3.85% |

15 Compound Forms Regardless of Principles of Implementation |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

38.88% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

33.37% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

16.14% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

11.56% |

247 Compound Letterforms (combination of individual letters two by two, according to compositional principles in Nastaliq |

|

Positive/Conjoined Massive |

57.47% |

Positive/Conjoined/Contour |

33.33% |

Positive/Compounded/Massive |

6.51% |

Positive/Compounded/Contour |

2.68% |