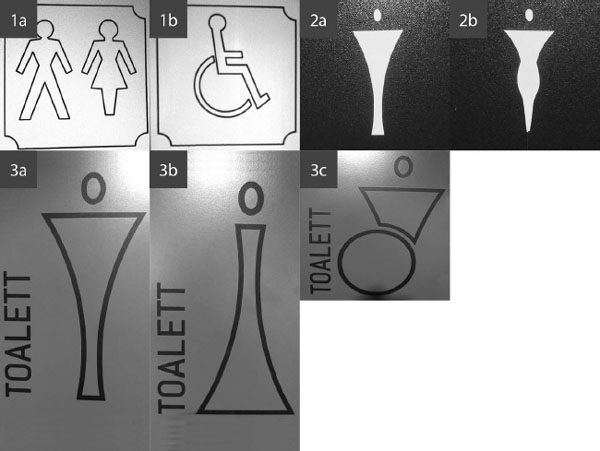

Figure 13.1 Toilet signs from educational context, sorted on a scale from naturalistic to abstract.

Signs, in the vernacular sense of the word, are all around us in our everyday life: on shops, street corners and traffic signs. Seen in passing, they are meant to be read quickly and efficiently, and to be designed in a way that will immediately be understood by passers-by with different backgrounds and competencies. This does not necessarily mean that these signs are semiotically simple. One reason for their semiotic complexity is that they are inherently embedded in the public space where they are placed, and must be understood as part of the social practices going on in this context. In this chapter I discuss toilet signs, more precisely, signs placed on toilet doors in public spaces. This material is of semiotic interest because toilet signs signify within public spaces very intimate and personal, albeit universal, human needs. Toilet signs have a specific ideational function of labeling a room for individual users in need, and placed on a door they represent a threshold between the public and the private that may challenge interpersonal and emotional aspects of communication. They adhere to conventions for marking the functions to be taken care of inside the door, and at the same time they are shaped to fit into the visual environment of the social practice taking place outside the door. The surrounding activity going on may vary from education (e.g. universities) to social and leisurely activities (e.g. restaurants).

Christian Mosbæk Johannessen (2013) has studied Danish toilet signs in a corpus-based and systemic approach. Referring to Abdullah and Hübner, 2006 he sorts his material in pictograms and icons. In this context pictograms are signs that are meant to be “immediately decipherable”, and icons “are primarily used to communicate messages in a fun way, and therefore enjoy much greater freedom of design” (Abdullah and Hübner, 2006: 6 in Johannessen, 2013). In passing Johannessen also mentions a convergence between sign types and the kind of contexts in which they were placed. The standard ‘pictogram’ type seems to be preferred in public administration contexts whereas the more varied ‘icons’ seemed to be preferred in restaurant or bar settings. Johannessen’s analysis pays most attention to the pictograms and their variations within a rather strict graphic frame. My material is of a different kind, since my interest has been in the great variation in motif as well as in materiality and style.

I am intrigued to see how such mundane practices as going to the toilet can bring about so much creativity, involving so many considerations in choice of motif, material (from permanent to provisional), style (from formal to ironic) and so on. In public spaces toilets are required but not part of the main purpose of the place. The easy way out, the unmarked choice, would be to use mass-produced standard signs. Any other choice marks a deliberation not only to communicate a pragmatic function but also to make traces that connect to specific social practices, that address certain groups of people, and that bear witness of preferred ways of being. The signs may be seen as part of interior decoration and, as such, may make the place stand out as different from other places, expressing identity through style (Fairclough, 2003; van Leeuwen, 2005). The purpose of my social semiotic approach is to deepen our understanding of how meaning is made in relation to social practice, through material production of traces in a particular environment. At a more general level this may contribute to how we see social structures in the world around us.

My interest in this area started when my university opened a new campus, where several people told me they had problems identifying the gender meaning of the signs on the toilet door (2a–b in Figure 13.1). The signs were part of a minimalist interior decoration style, depicting the human body in a very abstract way. Since a main idea of pictograms is that they should be easily recognisable, in this case the simplifying of bodily traits may have gone too far to communicate efficiently. Such processes of simplification or abstraction imply extracting the most significant differences between the male and female body, and leaving out others. In my view this is a question of how reality is constructed through representation of what we perceive as significant differences. But my collection of toilet signs also tells me that purposes other than efficient communication may be involved, raising questions of aesthetic preferences, style and identity.

My research questions for this chapter are, How are toilet signs anchored in the public space where they are placed, and how are identities and social constructs communicated through motif and style? In my analysis I sort the collected signs according to the kind of public space they were situated in and discuss what kind of identities toilet signs may afford within these social practices. This frames my analysis of motifs, materials and visual style, and in the next instance form the basis for reflections on how the toilet signs contribute to how we construe the world around us.

A basic understanding in social semiotics is that semiotic resources for making meaning are closely connected to the social context, and the influence goes both ways: semiotic systems both shape and are shaped by social systems (Halliday, 1978). Inspired by critical discourse analysis my analysis will involve three levels and the relations between them: the levels of text, discursive orders, and social structures (Fairclough, 1989: 73; 2003: 2). The individual toilet sign can be seen as a text, a semantic unit conveying meaning (Halliday and Hasan, 1985). In the context of this book it is also interesting to see it as a trace, underlining the material form as well as the process of producing the sign in a material medium. This combination of form and meaning is situated in a context that is, on one hand, discursive; it enters into an established discursive order of discourses, genres and styles (Fairclough, 2003) and, on the other hand, part of a social practice. In the following I present theoretical perspectives with emphasis on style, particularly relevant to how identity is expressed. In order to follow up the relations between meanings (sign as text) and material forms (traces) I refer to Scollon and Scollon’s theory of Discourses in Place (2003).

Following from the dialogical relationship between social systems and semiotic systems stated earlier, the social context is where my analysis begins and ends. The toilet signs must be understood within the context where they are situated and contribute to the construction of social meaning. The context can be seen as a result of the activities going on, in terms of organisation, such as universities, restaurants, museums and theatres in my case. At the same time the context is geographically placed and materially shaped. Toilet signs belong to the environment of our everyday lives which are saturated with semiotic meaning in ways we usually don’t even notice. Perhaps that is why my attention has been drawn to the signs that stand out as different, as clearly communicating more than (seemingly) neutral information about what can be found behind a door. Ron and Suzie W. Scollon state that “[m]ost of the semiotic systems which we index in daily life are completely transparent and invisible to us”, and they go on to point out that these systems “form the sociopolitical systems that so closely define us and our actions in the world” (Scollon and Scollon, 2003: 6). These are signs that “take a major part of their meaning from how and where they are placed” (Scollon and Scollon, 2003: 2). Scollon and Scollon have introduced the term “geosemiotics” for an integral view on the social meanings of how signs are placed in the material world. They suggest a combination of theoretical perspectives from interaction order, visual semiotics and place semiotics. Since I have not studied actual interactions where users encounter the toilet signs, this dimension has to be assumed from my general experience with social practices in the places where my photographs were taken. My focus is on how the visual semiotics of the toilet signs can be understood in dialogue with the built environment and the social practices going on in the public spaces I have visited.

A central concept for understanding this relationship in geosemiotics is that of indexicality, underlining how the understanding of any sign depends on the context. The term is inspired by the triad of Charles S. Peirce: icon, index and symbol. The index is a sign that “is connected or points to its object of reference” (Scollon and Scollon, 2003: 212). Indexicality is not to be understood as a classification of signs, but as a function of meaning-making that is relevant in all semiosis. In the case of toilet signs, placement and direction are typical examples of indexical meaning. The sign is placed on the outside of the door, meant to be read while a person is searching for the toilet and to show where to go. With this placement it is also part of the interior decoration of the surrounding room and the social practices taking place there, including choices of style and aesthetics. Interesting questions will be to what extent the motif refers to the activity inside or on the outside and whether this reference is explicit or implicit.

In human geography (Tuan, 2003b) it has become common to distinguish between space and place for understanding the meaning of physical and geographical context. While space refers to the physical dimensions of the portion of the earth or the built environment that is defined as a unit, place includes the human or lived experience within that space. As the Chinese American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan puts it, “[p]laces are centers of felt value” (2003a [1977]: 5). This makes the concept of place particularly interesting to my discussion of how toilet signs may contribute to construction of identity through choice of style and how they may reveal social constructions of meaning and values.

The signs that I am analyzing are situated in a context where they may contribute to expressing the style of the localities, and hence, indirectly, the style of the people using them. I use the concept of style from critical discourse analysis (CDA) to focus on how semiotic meaning is expressed. Fairclough (2003: 27) links style to processes of identification, and points out style as “the discoursal aspect of ways of being, identities” (Fairclough, 2003: 159). In Fairclough’s model identification is one out of three “major types of text meaning”, developed in parallel to Michael Halliday’s (1978) metafunctions. Fairclough’s model differs from Halliday’s in that it distinguishes between identification and relational functions, which are grouped together in Halliday’s interpersonal metafunction (Fairclough, 1992: 64). Fairclough points to three aspects of how identification can be expressed through style: the relationship between the participants, for example formal/informal; mode, for example written or spoken, or in my case visual; and rhetorical mode, such as argumentative, descriptive or expository (Fairclough, 1992: 127).

Fairclough draws a distinction between personal and social aspects of identity (Fairclough, 2003: 160), where the social aspects relate to how a person is positioned in society in terms of stable sociological dimensions such as age, gender and class. Taking the personal aspects of identity into consideration allows for seeing the person as a social agent, who makes personal choices. The complexity of identity as a concept has been further developed by Theo van Leeuwen, who introduces the concept of lifestyles (2005: 144) as a phenomenon particularly relevant in a culture where identity is increasingly related to choices of consumption. Van Leeuwen refers to D. Chaney, who, in his book Lifestyles, points out that “[p]eople use lifestyles in everyday life to identify and explain wider complexes of identity and affiliation” (Chaney, 1996: 12). One way of expressing lifestyle is through particular types of aesthetic choice. Lifestyle is social, since it defines the members of a group through resemblance in consumption and activities. But it is also personal, since lifestyle leaves more room for personal choice than a prepositioned social identity of class, for instance. The choices of where to dine and where to travel may be typical markers of lifestyle. And one person can have affiliations with more than one lifestyle. Van Leeuwen sees lifestyle groups as “interpretive communities” defined by shared taste, attitudes and ideas (van Leeuwen, 2005: 145, with reference to Fish, 1980). Producers of consumer goods offer ‘lifestyle signifiers’ that connect consumption to expressive meaning.

I find the concept of lifestyle particularly interesting for analyzing the public spaces where my examples have been situated, which include social practices that people engage in by choice. For places that offer consumer goods, lifestyle opens diverse possibilities for signaling what kind of people are expected to use the facilities and how the hosts intend to make them feel at home within their spaces and activities. The concept of lifestyle is socially defined, yet it leaves room for expressing individuality or identity in ways that make these places stand out from other organisations of a similar kind. According to Theo van Leeuwen, signifiers of lifestyle rest primarily on connotation, “signs that are already loaded with cultural meaning” (van Leeuwen, 2005: 146).

The area of feelings, emotions, evaluation and stances towards things is expressed through what in social semiotics is called modality. While van Leeuwen (2005) singles out modality as a separate dimension of semiotic analysis, Norman Fairclough points to the connection between identity and modality. Both modality and evaluation is a question of what the producers of text commit themselves to. “My assumption is that what people commit themselves to in texts is an important part of how they identify themselves, the texturing of identities” (Fairclough, 2003: 164).

Visual modality cannot be described with generalised criteria; different criteria may apply, depending on the setting in which modality is expressed and the function it fulfils. In their discussion of visual modality Kress and van Leeuwen (2006: 165) distinguish between four different coding orientations (naturalistic, abstract, technological, and sensory), referring to Basil Bernstein’s work on codes and communication in educational settings. Bernstein explains codes as “culturally determined positioning devices” (Bernstein, 2003 [1990]: 13). Their function is to connect specialised interactional practices with certain forms of textual production (Bernstein, 2003 [1990]: 18). Bernstein argues that coding orientation is connected to the social division of labour. He distinguishes between particularistic, local and context-dependent meanings in the restricted code, and universalistic, more local and less context-dependent meanings in the elaborated code (Bernstein, 2003 [1990]: 96).

In my discussion I will return to such possible connections between social practices and coding orientation.

The material to be analysed in this chapter consists of 55 toilet signs, collected from 25 locations. The sample has been collected through a period of six years (2008–2014) in public spaces I have visited, through work and private travels. A few of the images have been sent to me by friends and colleagues who heard about my project. This means that although the material is publicly available to anyone, the selection may be skewed, since it mirrors the interests and life experiences of a middle-aged female academic. I did not have the intention to create a representative sample or of photographing every toilet sign I have encountered on my way. Rather, I have given preference to signs standing out from the ordinary. I have included only two signs (one set) of the standard type, since new instances would only add numbers to my material, not variety.1 The fact that my collection contains only seven signs from academic institutions, compared to a total of 39 from the context of restaurants and travels, does not indicate that I have spent more time in restaurants than in universities. It can be explained by the fact that academic and educational institutions seem to favour abstract standard signs (Johannessen, 2013), and these are represented only once in my sample. Hence, my material mirrors my semiotic and stylistic interests, rather than representing the totality of my (or anyone else’s) experiences.

All signs in public places depend on some degree of simplification in order to communicate effectively, but they differ in degree of abstraction. Figures 13.1 through 13.3 give an overview of the material, sorted according to three types of locations, and on a scale from naturalistic to abstract. In my analysis I refer to examples using a number (for the set) and a letter (indicating which part of the set I refer to). Not all my examples are what I would call full sets of signs, including male, female and handicap toilet. All but two include both male and female, in one case (Figure 13.3, 22) because I was not able to find a parallel female sign and in the other because the photo was sent to me by a friend who probably found the female sign (Figure 13.3, 13) particularly interesting. In addition I have three locations where the signs include both genders (Figure 13.1, 1a; Figure 13.3, 7a–e and 12) since the same toilets were used by both. Seven sets include separate signs for handicap toilets; in most of the other cases I have not been able to find a handicap toilet. Three of the sets include signs for baby care, in two cases combined with female toilets (Figure 13.3, 14b and 17b) and in one with handicap toilet (Figure 13.2, 6c).

My analysis is mainly directed towards the visual image. Quite a few of the signs also contain the verbal written mode, underlining either the function of the room: ‘WC’ or ‘Toalett’ (the polite Norwegian word for toilet), or naming the group of people to use the facilities (‘gents’, ‘ladies’, ‘messieurs’, ‘mdames’, ‘baby changing’). These verbal expressions will only be commented on when they add to the dimensions analysed.

The first step in my analysis is sorting the material according to what kind of public space the signs were found in, asking what toilet signs can afford within the social practices going on in these contexts. These affordances will frame the next step in the analysis, focusing on the motifs and materialities of the actual toilet signs. Moving on to the level of discursive order, I will discuss how these examples of the genre toilet signs express style, and how these choices can be seen as markers of identity and attached values. The final step will be a discussion of how these signs contribute to social constructs.

In general, going to the toilet in a public space is a question of necessity that needs to be handled with some kind of discretion. This may be obtained through choices of motif and material form that tune down the attention to what is actually taking place inside the door. One way may be through abstraction; another may be to choose motifs oriented outwards towards the social practice outside the toilet door.

The signs that I have collected can be sorted roughly as belonging in three types of social practices: Education (Figure 13.1), Institutions of Culture (Figure 13.2) and restaurants and tourist destinations (Figure 13.3). Seven signs are from one university, from two different campuses (Figure 13.3, 1–3). Nine are from institutions of culture (a theatre/concert hall, a museum and an organisation for graphic designers; (Figure 13.2, 4–6)). The remaining 39 signs (Figures 13.3 and 13.4) are from contexts of travel and tourism, mostly restaurants and cafés but also including an airport (Figure 13.3, 22) and a tourist center (Figure 13.3, 24). In a few cases the categorisation may be debatable: Two signs are from a café in a museum context in Old Town, San Diego ((Figure 13.3, 17a–c), and two are from a combined book shop and café in the book town Hay-on-Wye in Wales ((Figure 13.3, 9a–b).

My examples from the educational field are few, but that can be explained by the fact that the sampling was driven by the interest in finding the greatest variety possible. Consequently, my material indirectly shows that this variety is not typically found in academic institutions. Assuming that a state university is stylistically related to public administration contexts, this is in line with Johannessen’s findings (2013: 176). These are institutions that people mostly visit on a regular basis. Students typically go to the same university for three or five years. Their movements become habitual, which means that toilet signs do not have need to draw attention to their existence by standing out from the ordinary. They serve a pragmatic function the way pictograms are meant to, doing their job “clearly, quietly and modestly” (Johannessen, 2013: 151). Going to the toilet in a university setting is connected to taking a break where bodily needs are foregrounded and academic life left in the background. Still, the academic context set its marks in choices of more or less formal style and in a systematic use of signs throughout the institution.

The social practice of visiting cultural institutions like theatres, exhibitions and museums is more related to that of eating out and travelling. These are contexts apart from every day, habitual life, in most cases connected to leisure time activity, and hence, the element of choice comes to the fore. Habits may be involved in both cases, for example with groups of people who go regularly to the theatre or are regular guests at a restaurant. But unlike the university, institutions of culture and leisure need to convince their visitors to come and, each time, to choose that particular place over other alternatives. This indicates a need to stand out as original. Visiting cultural institutions is connected to a certain kind of cultural capital, involving some kind of intellectual/spiritual enlightenment. In this context toilet signs may contribute to the cultural profile and the felt values of the place (Tuan, 2003a, 2003b) in terms of artistic styles, and they may also position the organisation in a range of formal/informal style.

The greater variety of public toilet signs from restaurants and other tourist destinations in my material is found within a social practice where it may be even more important to mark a specific identity as standing out from other alternatives. Choosing a restaurant to dine in can be a marker of lifestyle, expressing taste and expertise, even though the ultimate purpose of the visit is to satisfy bodily needs. Taste may be expressed through certain activities, or local or historical markers of belonging. One option would be a narrative rhetorical mode, telling a story the guests want to be part of. In public places for leisure and pleasure, going to the toilet may involve an extra social dimension, as in the habit of girls/women going to the toilet together to ‘powder their nose’. The informal space outside the actual toilet boots provides a break, a time-out outside the busy and demanding social space of eating out.

As can be seen from Figures 13.1 through 13.3, the total sample shows a fairly even balance between abstract and more naturalistic signs, but the distribution differs according to social context. In my material all the signs found in the context of education are abstract. Within the cultural institutions visited, six signs are abstract and three are more naturalistic. Within the field of tourism and travel a majority of 12 locations have naturalistic toilet signs, and seven lean to the abstract side. In the material taken as a whole, I find a tendency to abstraction in the educational and cultural contexts, and a tendency to naturalistic modality dominating in the field of dining and travels. This pattern may be related to the kind of social practice going on. Below I will discuss how affordances of abstract and naturalistic coding may relate to differences in motifs and style.

The main motif throughout my material is the human figure. The only exception is a set depicting moose (Figure 13.3, 14a–b), in this case the family constellation (ox and cow with ‘baby’) may be taken as a metaphor for a human family. Only one set of signs (Figure 13.3, 9a–b) includes the actual toilet in the picture. The focus on the human figure may be seen as a consequence of the need to distinguish male from female in toilets conventionally divided according to gender. But human figures are also used when toilets are for both genders (Figure 13.1, 1a; Figure 3.3, 7a–e and 12). Another function of diverting attention from the concrete toilet to the human figure is to create a distance to the intimacy inside. This distance may be increased through abstraction but also in the more naturalistically oriented signs by focusing on markers of local or historical belonging. In almost all of my examples, be they abstract or naturalistic, the depiction of the human body avoids intimate details, either by showing stylised versions of body and clothing or by showing only the upper part of the body. The norm seems to be that no one should have to be embarrassed by the signs pointing to the intimacy inside the doors.

I have counted as abstract all the signs that reduce the human head to a circle with no facial features. These go along with bodies that are in some way or other abstracted. This can be seen in the signs from the university, which are characterised by a minimum of detail, and a repetition of forms. One can distinguish head from body, but there are no arms and no legs (Figure 13.1, 2a–b, 3a–b). The lack of recognisable details demands some effort by the person reading the sign, since the distinction between male and female can most easily be seen when the two signs are considered together. The minimalist approach can also be seen in the materiality of the sign, a simple contour filled in with yellow on a flat surface (Figure 13.1, 2a–b). In the other campus the figures are drawn with an even black line, painted directly on the toilet doors (Figure 13.1, 3a–c), integrating the traces permanently in the interior.

Abstraction taken to its extreme can also be found in restaurant settings: The example from Bar Masa in New York (Figure 13.3, 25a–b) represents the male body with two straight lines (presumably representing trousers legs) in opposition to the female dress represented as a triangle. These signs may also be understood as playing with the features children first pick up in their drawings of the human body, connecting the legs directly to the head. The signs from a hotel in Kristiansand (Figure 13.3, 24a–b) have a similar style, particularly for the female figure consisting of head and skirt, with arms (or braids?) directly connected to the head. In both cases the abstract figures are imprinted on hard surfaces of metal and glass, underlining these traces as universal and timeless.

In the cultural institutions in my material the connection to a minimalist standard can also be seen, but in all three locations a little twist is added. The minimalist approach is most clearly seen in the signs from a museum in Edinburgh (6a–c), where the human body is represented as a geometrical shape under the circle representing the head. The twist here is in the choice of a crisp green colour, painted directly on the grey surface of the door. The other setting using abstract signs is an organisation for graphic designers in Oslo (Figure 13.2, 5a–c), where I found a playful approach to the regularity of the standardised shapes. The figures are slightly asymmetrical, and the lines are rounded and not quite even in thickness, leaving an impression of handwriting, which contrasts to the permanence of the metal surface it is engraved on. This could be a way of signaling a formal and serious organisation yet leaving room for individual creativity.

Some of the abstract signs from the group of restaurants and travel achieve a similar effect through some form of exaggeration compared to the standard. In Trollstigen Tourist Centre the signs are integrated in full size as part of the glass door (Figure 13.3, 23a–c). My example from Bergen Airport (Figure 13.3, 22) uses the same exaggerated size painted directly on the door, but in addition the standard sign is literally twisted, with a knee bend that signalises acute needs.

Summing up, the abstract toilet signs simplify the human figure in ways that make it impersonally distanced and universal, but still mark their style through choice of material, colour and shape in accordance with the context where they are placed. In the context of education, and to some extent in cultural institutions, I find this achieved through a minimalist style and durable materials. In the more commercial settings of restaurants and travel the typical style is marked by exaggeration.

Among the more naturalistic signs, ten show a degree of abstraction in that they are contour figures without facial features, but with individualising traits shown in clothing, hair style or body language. At the other end of the scale the most detailed pictures are family photographs in black and white, showing head and shoulders of actual people against a neutral background (Figure 13.3, 7a–e). A similar degree of natural depiction is found in Figure 13.3, 15a–b and 16a–b from restaurants on the Greek island of Lesvos.

The degree of detail in naturalistic images opens up to recognisable references to fashion in clothing and hairstyle. Sixteen of these signs are reduced to the upper part of the body, choosing to represent the body through its least private parts. In five signs the most significant detail is that the figures are wearing hats. These hats connote class (Figure 13.3, 17a–b and 18a–b), and to some extent they also signal a distant historical period. This impression is strengthened by the male figures wearing tie or bowtie, a dress code emphasised in spite of the rest of the figure being void of detail. In set 16 (Figure 13.3) only the male figure is wearing a hat, while the most prominent female has a hairstyle typical of the 1960s, a dress and high-heeled shoes. The two other sets are half figures, where the emphasis on the hats may replace distinguishing attributes in clothing (skirts) and body shape. All of these examples are from restaurants. By choosing this kind of toilet signs they communicate to customers of a certain age, and belonging in a class that remembers when restaurant visits were reserved for a certain dress code (i.e. tie).

A related, yet contrasting example can be found in the concert/theatre house in Kristiansand that opened in 2012. Here the toilet signs are white silhouettes on black doors, depicting a more laid-back and modern dress code (Figure 13.2, 4a–c), as can be seen clearly in the position of the male body and in the uneven lines of the trousers (Figure 13.2, 4a). A very discrete reminiscence of the male suit can be seen as his breast pocket is marked with a handkerchief. These signs connote a modern and informal way of life. Still, the setting is marked as lasting since the images are painted directly on the door.

Typical local markers are seen in 13, (Figure 13.3) which shows a national costume from the region of Setesdal in Norway. Another way of marking the same rural culture is seen in 14a and b (Figure 13.3), where the figures depicted are moose (underlined verbally: “ox”, “cow” and “baby”). These signs were found in a café in a small rural town in an area where moose hunting is a popular leisure activity. The same kind of locally rooted detail is found in two settings in Greece. In Figure 13.3 10a–b clothing marks the local; in 11a–b, the local is marked through references to Greek mythology.

Historical references can be seen in clothing (for instance in Figure 13.3, 17 and 18) hairdo (Figure 13.3, 16b) and interiors. In Figure 13.3, 9a–b, photographed in a book café in the Welsh book town Hay-on-Wye, an old-fashioned style of interior is displayed, as well as the persons’ clothes and hairdo. Clothing and hair styles also mark out a certain historical period in sign 12 (Figure 13.3), found in a restaurant at the seaside in San Francisco and in the family photographs (Figure 13.3, 7a–e) used as toilet signs in a restaurant in the docklands of Oslo. In one of these photos we see three persons in old-fashioned swim suits (7a); in another, a man is wearing a traditional student hat connoting higher education (7d). This combination of physical and intellectual activity indicates a certain class. So, too, does the style of photography and the frames in noble wood. A similar kind of framing can be seen in 8a referring to a historical person, the Dano-Norwegian nobleman Peter Wessel Tordenskiold, renowned for leading the battle against Sweden in the great Nordic war (1700–1721). The sign features a famous portrait of the naval hero, with a nametag to make sure he is recognised. His female counterpart (8b), however, has neither name nor title but is probably chosen to fit his time, class and style. Her body posture is in the same direction as the male, but her body is turned away from the viewer, and her head is slightly bowed, indicating a humbler position. This is placed in a restaurant in a coastal area where well-to-do tourists in eastern Norway spend their summers. The historical reference is national more than local, but Tordenskiold’s connection to life at sea at the same time connects to the local identity. Such historical motifs at the same time connote class and power in ways that I will return to in the next part of my analysis.

The naturalistic toilet signs that dominate in settings of tourism and travel display a great variety of details that emphasise particular connections to time, place, interests and social groups. In many cases the signs indicate a narrative rhetorical mode, where the visitors are invited to step into a story of mythology (Figure 13.3, 11), hunting (Figure 13.3, 14) or historical bravery (Figure 13.3, 8a), to mention but a few examples. This goes along with a great variety of materials and techniques like carved or painted wood (Figure 13.3, 9, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18) slate (12), ceramics (10) moulded brass (11), photographs (7, 8) and drawing on paper (21). The particularity of these signs is seen in the meanings of the motifs, as well as in the processes of production. With few exceptions these signs are not mass-produced, nor are they integrated (in terms of material or design) in the architecture. They carry added value that may be exchanged by choice.

As shown in my analysis the motifs in the toilet signs may signal affiliation with certain roles or positions through connotation. These may be concrete and particular in their references to activities or styles of clothing, or more abstract and general. Throughout the material I see a division that may be explained as a difference in coding orientation (Bernstein, 2003[1990]): between naturalistic and abstract, particularistic and universal, informal and formal. To a large extent the abstract, universal and formal motifs are produced on, or rather integrated in, materials of a lasting kind; they signal permanence as part of a holistic design.

This is most obvious in the toilet signs in the university campuses (Figure 13.1) which are designed to be part of the design program that unites the whole campus through similar aesthetic choices. Lecture, seminar and group rooms are marked with similar signs using the upper part of the figure in the toilet signs to represent persons, and varying the number of figures according to the activities going on inside the room.

Hence, the signs in the university setting can be seen as part of a minimalist standardised design. This marks the institution out as a well-planned totality where nothing is left to chance. The design gives priority to elegant lines rather than distinctive form. The aesthetic choices connote modern lifestyle and serious values. The abstract and formal are open to identification by anyone, tuning down personal experiences and preferences. These choices of style may be connected to the academic activity going on in this place, in which abstraction plays a central role, and bodily needs are not emphasised.

Direct references to class and power I have found mostly in naturalistic signs that point back in history, to persons with wealth and power or to clothing that indicates the same. This is often underlined by frames that are prominent in size and shape, and exclusive in material. This indicates that a stable system of class seems to be rooted in the past. When such traditional markers of wealth and power are included in modern restaurant settings, they are turned into markers of lifestyle that can be consumed by choice. In some cases the nostalgia may be of a kind that invites to a certain irony and self-depreciation (Figure 13.3, 7a–e), communicating to visitors whose reflexive identification may include a distanced view of their own social class.

In a more indirect sense the universalistic style of the academic and cultural institutions, which is seemingly open to ‘anyone’, may also indicate social class, as Basil Bernstein has shown in his work on coding orientation in education. Differences in coding orientation are connected to what is useful within specific social practices and to connected sets of social relations. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2006: 165), abstract coding orientations are used by “sociocultural elites” in contexts where general patterns are of interest. In other contexts, such as leisure time activities, other criteria for coding orientations may apply.

The most prominent arena for identification with a certain lifestyle through consumption and by choice is represented by the toilet signs from restaurants and tourism in my material. Particularistic motifs and exchangeable materials both indicate that style here is a matter of choice, of entering into various stories that may be exchanged with other stories on other occasions. Identity may be expressed in terms of nationality/location, class or historical period. A common feature in my examples of identification through certain activities, regions or historical periods is that indexicalisation is directed outward, to activities that may serve as markers of lifestyle, in which the social practice of eating out is embedded.

This forms a contrast to the few exceptions where toilet signs refer to the intimacy inside the toilet. These signs including actual toilets in the image (Figure 13.3, 9a–b), or are more or less bluntly physical in their depiction of male and female characteristics (Figure 13.3, 20a–b, 21), indicating that the norms of discretion can only be broken by creating an ironic distance.

My analysis of style shows that the choice of toilet signs is not primarily a question of representing the function behind the door in an efficient manner. Even more important, it seems, is doing it in ways that are acceptable within the norms established in the context and in styles that contribute to the sense of belonging through elegance or excess or humor.

Finally I return to the dialogical relationship between texts and social structures by briefly discussing how toilet signs may contribute to the way our understanding of the social world is shaped. Across the social practices that I have discussed I find that the signs mainly depict the human body. Conventionally the main distinction to be made by toilet signs is that between male and female. This is a social and not a naturally given division, and there are exceptions. Nine of the toilet doors in three locations (Figure 13.1, 1; Figure 13.3, 7 and 12) have signs depicting both male and female, signalling gender-neutral use. Even in these cases the motifs uphold heteronormativity in their binary division in two genders.2 However, the signs on handicap toilets do not distinguish between male and female, nor do signs where children are mentioned specifically. In my material, babies are included in the female sign in two cases (Figure 13.3, 14b and 17b), placing the care for children within the female domain, and in one case baby changing is placed in the handicap toilet (Figure 13.2, 6c).

All the abstract figures are presented frontally, the most conventional way of depicting a human body. In the naturalistic modality there is a much greater variety in body posture, but the face is always turned towards the viewer, presenting the human as a subject who invites contact and involvement (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006: 117). In contrast the signs on handicap toilets always depict the person in profile so that the wheel of the wheelchair stands out as the most prominent feature. The person is depicted with an oblique angle that signals a detached relation to the viewer (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006: 136). Overall these choices construct a world where being adult male or female is the norm, whereas children and handicapped are not classified on the basis of this dichotomy.

This leads to the next question: what are, according to this material, the “essential qualities” (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006: 165) that distinguish male and female? This question is particularly interesting in abstract signs, where the differences are placed in the body section, since all the heads have the same shape. I first have a look at the signs at my university, which caused some confusion. Here the difference between the male and the female body can be found in the waistline and the rounded hips of the female (2a–b). One could claim that the male figure appears to be the unmarked standard and that the waistline and hips are added, and hence marked, female qualities. However, if we move to the other campus of the university (3a–c), opened a few years later, none of the figures have a waistline. The distinction between male and female is made as a reversed symmetry where the broad shoulders of the male figure are repeated upside down in the skirt of the female figure. In this case it is interesting to note that the male figure is characterised by a bodily trait, whereas the female figure is characterised by the cultural feature of clothes. This could indicate that male is ‘naturally’ defined and female ‘culturally’.

Moving to the standard figures, I find two varieties of the female figure, one where her legs are collected to one shape (Figure 13.1, 1a) and the other displaying two straight legs under a dress (like in Figure 13.3, 23b). In the first standard both the figures have a waistline; in the other, neither of them has. Hence, we see that one of the essential distinctions in examples 2a–b (Figure 13.1) is not supported by the most common standards. In both standards the main distinguishing feature is dress, rather than bodily shape, and this cultural feature is more prominent in the female signs.

Clothing marks out culturally specific groups within a society. In the abstract signs the most salient piece of clothing is the female dress, which is always knee-long, indicating a convention of dress established in the middle of the 20th century. In the case of abstract male figures it may be hard to decide whether the figure should be read as the shape of body or clothes. This may indicate that nature and culture amalgamate in the social construction of the masculine as yet another way of placing male as the unmarked norm.

My material shows a great variety in how toilet doors may be marked in terms of what is represented, and how this is materialised. Signs—even of the most mundane kind—carry meaning that must be understood in relation to the social practices they are part of, and contribute to defining the “sociopolitical systems” referred to by Scollon and Scollon (2003: 6). The great variety of references to activities, fashion and historical periods indicates that the signs contribute to defining particular lifestyles, distinguishing not only between rich and poor but also between hunters and swimmers, traditional and modern, local and national and so on. Particularly in commercial social practices, places like restaurants and tourist destinations make a living from selling the “felt values” of a place, as referred to by Tuan (1977: 5). Institutions of education and culture likewise express their identity and values, mainly through abstraction and holistic design.

Approaching my material of toilet signs with a double perspective, seeing them at once as semiotic resources and traces involving materiality and the process of production, has brought the relations between meaning and form to the fore in my analysis. The choice of materials (hard, flat and lasting, or soft and easy to shape) contributes to the meaning of the sign a sense of permanence and stability, or dynamic engagement, respectively. Likewise, the process of making the traces (by mass production, templates or free hand, integrated in the materials of the building, or add-ons that can be exchanged) signals formality on a scale from firmness and permanence to flexibility and changeability.

A social semiotic framework contributes contextual understanding of how these acts of making traces afford meaning according to how they enter into social practices and are shaped within established orders of discourse. On the other hand, a focus on traces may serve as a reminder of how materials and processes contribute to meaning. Theoretically, the relations between meaning and form are included in multimodal approaches to social semiotics, most prominently in Kress and van Leeuwens work on multimodal discourse (2001), where the dimension of production emphasises material articulation or production (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001: 6). In practical analytical work, however, a better grasp of these dimensions could enrich the semiotic argument.

In the simple event of going to the toilet in a public space, meaning is made in relation to what the sign represents and how this is given form, and in relation to the bodily and social practice going on inside and outside the door. Ultimately, these brief encounters may tell us something about how we see ourselves, our affiliations and our values and how we organise our world.

1My example (1a–b in Figure 13.1) is taken from the older part of my university campus. This pictogram resembles the one issued by Danish standard, according to Johannessen 2013, p. 150. My example has sharper corners and uses a black outline on white background.

2Gender neutral restroom signs have recently been installed in significant places like the White House (www.politico.com/story/2015/04/white-house-gender-neutral-bathroom-116779) in respect for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.

Abdullah, R., and Hübner, R. (2006). Pictograms, Icons & Signs: A Guide to Information Graphics. London: Thames and Hudson.

Bernstein, B. (2003 [1990]). The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. Vol V: Class, Codes and Control. London: Routledge.

Chaney, D. (1996). Lifestyles. London: Routledge.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and Power. London: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analyzing Discourse. London and New York: Routledge.

Fish, S. (1980). Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as Social Semiotics. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Hasan, R. (1985). Language, Context and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective. London: Cambridge University Press.

Johannessen, C. M. (2013, October). A corpus-based approach to Danish toilet signs. In RASK, Internationalt tidsskrift for sprog og kommunikation (Vol. 39, pp. 149–183). Odense: Department of Language and Communication, University of Southern Denmark.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Hodder Arnold.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London and New York: Routledge.

Scollon, R., and Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London and New York: Routledge.

Tuan, Y-F. (2003a/1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tuan, Y-F. (2003b). On human geography. Deadalus 132(2), 134–137.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing Social Semiotics. London and New York: Routledge.