I wish we were a nice family,” Chris said. He and his parents and sister sat around the secondhand dinner table, eating hot dogs and canned baked beans and macaroni and cheese that had come from a box.

“What the heck is that supposed to mean?” Chris’s dad said. He was still wearing his uniform from the garage with his name, DAVE, stitched in cursive letters over the shirt’s breast pocket. “Do you think we’re all a bunch of jerks or something? I mean, look at your mom—is this the face of somebody who isn’t nice?”

Chris’s mom flashed an exaggerated angelic smile and fluttered her mascara-painted eyelashes.

“And what about your little sister here—she’s not nice?” Chris’s dad pointed a forkful of macaroni and cheese in Emma’s direction.

“I’m very nice,” Emma said, pushing her glasses up on her freckled nose. She was in fourth grade and was, Chris thought, bossy beyond her years. She gestured at her green uniform, complete with a sash full of badges. “I’m a Girl Scout and everything.”

“See? It doesn’t get nicer than that,” Chris’s dad said. “And everybody who knows me says I’m reasonably nice—the guys at the garage, my customers, my buddies I go bowling with. People tend to like me. Or at least, they generally don’t run away when they see me approaching them.” He reached for another hot dog—a mistake, given his growing waistline, Chris thought—and squirted it with an excessive amount of mustard. “So what do you mean when you say our family isn’t nice?”

Chris felt like his father had misunderstood him. This was a regular occurrence. “No, you’re all nice people,” Chris said. “That wasn’t what I meant. What I meant was”—Chris searched in vain for words that would express his thoughts without offending his family members—“I guess I don’t know what I meant.”

But really, Chris knew exactly what he had meant. His parents were decent people: good citizens who loved their kids and worked hard for their family and community. His little sister was annoying in the way younger siblings were, but he would never say she was a bad person. That being said, when he compared his family to the families of the smartest kids in school, they fell short.

Part of it was his parents’ education, or lack thereof. His mom had started working as soon as she graduated high school and still had the same job at the utility board she had gotten when she was eighteen. After Chris’s dad finished high school, he had gone to vocational school to learn how to work on cars. He had an excellent reputation as an auto mechanic, but that job didn’t strike Chris as prestigious enough. His dad came home every day dirty and smelling like axle grease. In Chris’s opinion, truly successful people didn’t need to take a shower as soon as they got home from work.

When Chris went out with his parents, to a restaurant or a store or a school function, he always felt embarrassed. His mom was loud and flashy. She wore the brightest colors she could find with the reddest lipstick and the biggest, shiniest costume jewelry.

His dad, despite his daily after-work showers, always had grease under his fingernails, so he never looked quite clean. And then there was the matter of his weight. Chris’s dad’s belly protruded over his belt, and sometimes his shirt rode up such that the great shelf of his distended gut escaped and hung out for all to see. When he sat and his pants slipped down and his shirt rode up in the back, what he exposed was even worse.

Chris knew his parents were nice. He just wished they could look nice and act appropriately in public. The smartest kids at school had parents who always knew how to look and act. The dads wore jackets and ties or khakis and polos. The moms wore tasteful blouses and dress slacks and subtle, expensive jewelry and makeup. These parents were professionals: lawyers or engineers or medical doctors. They had careers that required years of schooling beyond high school. This was the kind of career Chris wanted.

The kinds of jobs that Chris’s parents worked led to a deficiency in another area: money. They weren’t poor, no. They owned their house, but it was a plain, dumpy house, barely big enough for a family of four, and the furniture was mostly hand-me-downs from Chris’s grandparents. His mom and dad each had a car, but both of the vehicles were ancient and only kept running because of his dad’s mechanical know-how. They had a creaky old shared family computer, and Chris’s video game console was so tragically out of date he couldn’t buy new games for it anymore. They only got basic cable. Honestly, who just had basic cable these days?

When Chris rode around town on the school bus, he always noticed the subdivisions that were full of fancy, two-story brick houses. He liked to fantasize about the families who lived in them: the doctor dads and lawyer moms and their high-achieving kids, all dressed in designer clothes, eating grilled salmon and steamed vegetables and salad for dinner and then lounging in rooms that looked like they were ready to be photographed for one of the home-and-garden magazines he always saw in the waiting room at the doctor’s office. The parents probably played golf and tennis at the country club while their kids splashed around in the pool. There were never any worries about how to pay for the kids’ college once they were old enough.

That’s what Chris had meant by wishing they were a nice family. He wanted a nice life for them, with nice things, and a bright future for him and his sister. Surely it wasn’t so wrong to want more out of life than scraping by every month just to pay the bills, then having to buy the off-brand items at the grocery store just to save a few cents.

“Emma, it’s your turn to do the dishes tonight,” Chris’s mom said as they were finishing their meal.

“Okay, Mom,” Emma said. It annoyed Chris how cooperative she always was. Didn’t she ever get sick of doing the same chores over and over?

“Chris, I told Mrs. Thomas you’d help take out her trash tonight,” Mom said, getting up from the table. “After that, you can take Porkchop for his after-dinner walk.”

Chris didn’t want to do either of these tasks. Why were parents always exploiting kids for free labor? “Mom,” he said, trying to keep his voice from rising to a whine, “I’m busy. Tomorrow’s the first day of school, and I’ve got to get ready.”

“Taking out Mrs. Thomas’s trash and walking Porkchop will take thirty minutes, tops. That gives you plenty of time to get your stuff ready for school tomorrow.”

He could tell from the tone of his mom’s voice that she wasn’t going to put up with any argument. “Okay, but I won’t like it.”

“I know you won’t like it,” his mom said. “It’s part of my evil plan to oppress you.” She did a fake laugh like a villain in a cartoon. “Come on, I’m trying to make you laugh here.”

Emma, who was already clearing the table, laughed, but Chris wouldn’t give his mother the satisfaction. With a theatrical sigh, he got up from the table and left by the back door to go to Mrs. Thomas’s house.

Mrs. Thomas was old, so old that Chris’s parents were always amazed that she still managed to live alone and take care of herself. She had been a high school English teacher for over forty years, teaching Chris’s parents along with many generations of the town’s high school students. Now, though, she had been retired and widowed for many years and lived in a small, boxy, book-cluttered house with just her cats for company. She cooked and did light housekeeping herself, but Chris’s parents helped her out with anything that required heavy lifting.

Or, at least in the case of the garbage, they forced Chris to help her. The arrangement was that on the night before garbage day, Chris would come to Mrs. Thomas’s house, empty all the trash cans in the house, and take the bags to the big garbage pail in her driveway, which he would then take to the side of the road so it would be ready for pickup the next morning.

Chris had once asked his dad if he could at least be paid for this weekly responsibility, but his dad had said, “Sometimes you don’t do a job for money. You do it because it’s the decent thing to do.”

Chris had taken that as a no.

Chris knocked on Mrs. Thomas’s door and prepared to wait. She moved slowly, and it always took her a long time to answer. When she finally came to the door, she was wearing the same yellow cardigan she wore year-round, even now when it was hot outside. She was a tiny, delicate, birdlike woman. Her glasses were thick, and her hair was thin and gray. “Hello, Christopher. It’s so nice of you to come over and help me.”

She was the only person who ever called him Christopher.

“Sure,” Chris said. But really, it wasn’t a matter of being nice. It was more that he was still a kid and so when his parents made him do something, his only choice was to do it or suffer the consequences.

“Please come in,” she said, holding the door open. “There’s just one bag of trash that needs to go out. It’s in the kitchen.”

The house was dark and smelled musty. The walls were lined with full bookshelves, and every piece of furniture in the living room had at least one cat sleeping on it. He followed her into the kitchen.

“Could I interest you in some cookies before I put you to work?” Mrs. Thomas asked, gesturing to the cat-shaped cookie jar on the kitchen counter.

“No thank you. I just had dinner.” Mrs. Thomas’s cookies were the cheap kind they sold at the ninety-nine-cents store, and they were always stale. After taking her up on the cookie offer twice, he had learned to say no.

“Well, that’s never stopped me from having a cookie or two,” Mrs. Thomas said, smiling. “Your mother tells me you’re starting high school tomorrow. That must be exciting for you.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Chris said, anxious for this conversation to end so he could get back to doing stuff that really mattered.

“She was bragging about what a good student you were and about how much you love to learn. You know, I taught at your high school for many years. English literature. If you ever need any help with anything academic, just let me know. And if you ever want to borrow any of my books, you’re always more than welcome to.”

“Thanks, but I’m more of a science guy than a literature guy.”

“Don’t put yourself in a pigeonhole yet. You’re too young,” Mrs. Thomas said. “And there’s absolutely no reason you can’t be both a science guy and a literature guy. There are so many wonderful things in the world to learn.”

Chris lifted the garbage bag, filled mostly with empty cat food tins, out of the trash can. “I’ll take this out and then roll the big can out to the road, okay?”

Mrs. Thomas nodded. “Thank you, Christopher. You’re such a great help to me.”

Chris walked back toward his yard. He knew Mrs. Thomas was trying to be nice, but it was kind of sad that she thought she could help him with school stuff. She had gone to the little local college a bazillion years ago, then taught high school English until she retired. It wasn’t like she was some great intellectual. Plus, she was so old she had probably forgotten what little she had known. He was sure she could teach him nothing.

Chris opened the gate to the fenced-in backyard, where Porkchop was wagging and waiting. As soon as Chris was inside, Porkchop jumped up on him and craned his neck so he could lick Chris’s face.

“Get down, Porkchop! You’re getting me all muddy!” Chris backed away from the dog’s dirty paws and tried to dust off his pants.

Chris had wanted a dog, but Porkchop was not the dog he had wanted. Chris had wanted one of the smart, beautiful purebred dogs he had seen on dog shows on TV: a border collie or a Shetland sheepdog. But his dad had said they couldn’t afford a purebred dog and that anyway, it was immoral to buy an expensive dog from a breeder when there were so many dogs in shelters that needed good homes.

And so one evening when Chris was in sixth grade, his dad had come home with Porkchop, a brown-and-tan, overgrown, snaggle-toothed shelter mutt who bore no resemblance to the elegant herding breeds Chris admired. It was immediately clear that Porkchop also lacked the intelligence to learn the tricks or agility skills Chris had dreamed of teaching a dog. Instead, Porkchop was a happy idiot whose favorite activities focused on his belly, either filling it or getting it rubbed.

“Ready for your walk?” Chris asked, without much enthusiasm.

Porkchop made up for Chris’s lack of enthusiasm by wagging, barking, and running in small circles.

“If you won’t sit, I can’t put your leash on,” Chris said. He couldn’t believe how much time he was wasting carrying out his parents’ orders.

He attached the leash to Porkchop’s collar. “Once around the block, and that’s all you get,” he said.

Walking through the neighborhood was depressing. The houses were small and identical little boxes, which had originally been built for the workers in a steel mill that had shut down many years before Chris was born. The yards on which the houses sat were postage-stamp small. He was sure he was the only kid in the Science Club who lived in such a lousy neighborhood. He hoped he could keep where he lived a secret from the other kids, who, he was sure, all lived in the fancy neighborhoods on the west side of town that had names like Wellington Manor and Kensington Estates.

As promised, he took Porkchop around the block once, then brought him in the house and emptied out a can of dog food into his bowl. Porkchop happily gobbled it up.

Finally, with his chores all done, Chris could go to his room and start getting ready for the first day of high school. Not only did he need to get his backpack filled and organized, but he also had to decide what he was going to wear. His mom had taken him shopping the week before and bought him five shirts, three pairs of jeans, and some new sneakers. But they had gone to this awful big-box store because the prices there were affordable. What Chris had picked out looked okay, but he wished he could have real, name-brand clothes from one of the good stores in the mall. His mom said nobody could tell the difference, but he knew this was a lie she told to try to make him feel better.

Still, Chris was feeling hopeful. The first day of high school was a fresh start, a chance for him to prove himself. A whole new ball game, as his dad would say; the man never met a cliché he didn’t like.

The thing that Chris was most excited about was joining Science Club. At West Valley High, Mr. Little’s science classes and the club he supervised were legendary. Mr. Little’s classroom was lit by plasma balls and lava lamps and strings of glowing bubble lights. He was famous for demonstrating spectacular experiments that involved fire or carefully controlled explosions, though he said he made sure his students didn’t work on anything that would put them in actual danger. He was also famous for jump-starting student projects that produced extraordinary results and almost always won science fairs when West Valley competed with other schools.

Science Club was famous for bringing back numerous trophies for West Valley, and Science Club students had the reputation of being the school’s highest achievers. On Freshman Orientation Day, when new students were given the opportunity to sign up for clubs, Chris had made a beeline for the Science Club table. It was the only club he signed up for. Why waste your time on anything inferior, Chris thought, when you can be with the best?

Chris was especially looking forward to this weekend, which was the traditional lock-in that Mr. Little held every year for his students. The entire class would spend the night at the school, working on a secret project of Mr. Little’s design. It had the reputation of being a life-changing experience, one that secured your status in Science Club and the school. Chris wanted his status to be the best of the best.

“Chris! Your friends are at the door!” Chris’s mom called from the living room.

Josh and Kyle, Chris thought. He felt vaguely annoyed. He had a lot of preparation to do to ensure he made the right impression on his first day. He was in a serious mood, and Josh and Kyle were never serious about anything. “Be there in a minute!” he yelled back.

He finished loading his backpack with school supplies before he went to the door. At least he could get that done despite the interruption.

Josh and Kyle were waiting in the living room. Josh had let his hair grow out over the summer, and it hung in dark brown waves over his shoulders. Kyle had dyed a purple streak in his hair and was wearing a T-shirt for some band with a skull and crossbones on it. Chris was a little nervous about the fact that Josh and Kyle would also be starting at West Valley High tomorrow. They had been his friends since they were preschoolers, but he hoped they wouldn’t hang all over him during school hours. They were nice guys, but he feared the image they projected wouldn’t go over well with the Science Club kids. He didn’t want his old friends to hold him back from making new, higher-status friends.

“Hey,” Josh said, pulling his hair back behind his ears, a habit he had picked up since letting it grow. “It’s our last night of freedom.”

“Yep,” Kyle said. “Tomorrow they lock us back up and throw away the key until next summer.”

“Actually, I’m kind of excited about going back to school,” Chris said. “I mean, it’s high school, you know?”

“Same thing with a different name,” Josh said, sounding like he was bored already. “We were gonna ride our bikes over to the Dairy Bar, then go down to the lake. You wanna come?”

Of course you are, Chris thought. It was what they always did. But he supposed he might as well come along for old times’ sake. Tomorrow, his life was going to change: It would be full of smart friends, science projects, and academic achievement. The bike rides and ice cream of childhood would just be a memory. “Sure, why not?”

He followed the boys outside and got his bike.

“Race you to the Dairy Bar!” Kyle yelled, like he always did.

They took off. Chris intentionally didn’t pedal as fast as Josh and Kyle. He figured he might as well let them win. There were many achievements in his future, so maybe he should let one of them win the race to have some small sense of accomplishment. Soon he would be leaving them in the dust in other ways.

Josh won. Not that it mattered.

At the Dairy Bar, they each ordered their customary chocolate-vanilla swirl cones and sat down at one of the wooden picnic tables to eat them. Even though the ice cream was good, Chris could still imagine better treats he would have in the future once he had risen to the social status he aspired to. Then he would eat luxurious desserts he had only read about or seen on TV: crêpes suzette, molten chocolate lava cake, crème brûlée.

“I haven’t seen you on the server much lately, Chris,” Kyle said. In middle school they had liked to “meet up” online to play Night Quest, a popular multiplayer game, together.

“Yeah, I guess I’ve just had more important things on my mind lately,” Chris said, licking his cone.

“Why? Is something wrong?” Josh asked. “Nobody in your family is sick or anything, are they?”

“No, nothing like that,” Chris said. “I’ve just been thinking about, you know, the future.”

“The future, like with robot overlords and flying cars?” Josh asked, grinning.

They were so incapable of being serious it was infuriating. “No,” Chris said, “like my future. My goals. What I want out of life.”

“That’s some pretty heavy thinking for summer break,” Kyle said. “At the beginning of the summer, I take my brain out, put it in a jar, put the jar on a shelf, and don’t take it out again until school starts.”

Josh laughed. “So that’s what you’ll be doing when you get home tonight? Putting your brain back in your head?”

“Nah, I’ll probably wait till the morning. No need to start thinking any sooner than I have to.”

Josh and Kyle were both laughing, but Chris couldn’t muster a smile. How did he even end up being friends with these losers? He supposed it was just because Josh lived next door and Kyle lived across the street. They had been flung together because they were the same age and lived in the same place. If Chris had grown up in a nicer neighborhood, he would have ended up with a better class of friends.

After they finished their ice cream, they got back on their bikes to go to the lake.

What they called the lake was really just a large pond. Once they got there, they did the usual. They looked for flat stones to skip across the water. They tried to approach the Canada geese, then laughed when the geese hissed at them. They talked about video games and internet memes and nothing in particular.

Looking out at the “lake” that was really a pond, Chris thought of the word stagnant. That pond was going nowhere. It wasn’t a river or even a little stream that flowed and went somewhere else, became a part of something bigger. Instead it just sat there, growing algae and gross bacteria, going nowhere and becoming nothing.

Unlike the pond, unlike Josh and Kyle, Chris had no intention of stagnating. He was going places.

Chris woke early on the first day of school. He took a shower, brushed his teeth aggressively, and applied a double coat of deodorant. He ran a little gel through his short, neatly cut sandy-brown hair to make sure it wasn’t going anyplace. He put on the polo shirt and khakis he had set out the night before. He wished again that they were a better brand, but at least they were clean and new.

“Hey, there’s my big freshman!” Mom said when he came into the kitchen. She assaulted him with a hug.

“Mom, stop,” Chris said, squirming away from her and sitting down at the table. He poured himself a bowl of cornflakes and started slicing a banana over them.

Mom sat down across from him, holding a cup of coffee. She had already done her hair and makeup for work. As always, it was a little too much, in Chris’s opinion. Her hair was dyed a shade of red that wasn’t found in nature, and she was wearing a leopard-print top, black leggings, and leopard-print shoes. He wished she would aspire to simple elegance instead of cheap glamour.

“I know you get tired of me talking about how big you’ve gotten,” she said. “But when you’re a parent someday, you’ll understand. You start out with this little, tiny baby with toes the size of corn kernels, and then it seems like no time passes till your baby’s so tall you have to look up at him!”

Chris didn’t comment, just crunched his cornflakes. What was there to say? He had grown. It was what kids did. It wasn’t like it was some great achievement or anything.

“Anyway, I’m proud of you,” his mom said. “Proud of your sister, too. It really seems like she should still be a baby, but you should’ve seen her this morning. She got herself all ready and walked to the bus stop. So independent.” She smiled. There was a little smear of lipstick on her front tooth. “Say, I don’t have to be at work till nine this morning. Do you want me to drive you in for your first day?”

Chris nearly choked on his cornflakes. He didn’t want the Science Club kids at his new school to see his overly made-up mom pull in with her ten-year-old economy car that rattled and wheezed like somebody’s great-grandpa. What kind of impression would that make? “No thanks, Mom. I’ll just take the bus.”

“What did I say? Independent.” His mom reached over and ruffled his hair. Now he would have to comb it again.

On the school bus, Josh and Kyle were sitting next to each other. When Chris boarded, Josh said, “Hey, Chris! Time to turn ourselves back in to the jailer, huh?”

Chris ignored him. There was an empty seat across the aisle from Josh and Kyle, but he ignored that, too, and found another empty seat farther back on the bus. It was better to be seen alone than to be seen in the wrong company. He looked around the bus, trying to figure out if any of the kids looked like they could be Science Club members.

West Valley High was much bigger and more crowded than Chris’s old middle school. In the hallways, he had to concentrate to keep from running anyone over and not to be run over himself. It was hard to concentrate on navigating the hallway when his brain was consumed by one thought: Third period is Mr. Little’s class. Third period is Mr. Little’s class.

After what felt like an eternity and a half, third period arrived. Chris and his classmates crowded into the room at the end of the hall and beheld the bizarre wonders of Mr. Little’s classroom. Chris took a seat and looked around. The walls were plastered with posters, some outlining the scientific method or showing cell structure, others displaying science-related puns and wordplay. One said, IN SCIENCE, MATTER MATTERS, and another, THINK LIKE A PROTON. STAY POSITIVE. The shelves that lined the room were filled with more scientific curiosities than Chris could take in at once. The one nearest him displayed a variety of glass jars filled with clear fluid and different biological specimens. One jar held some poor creature’s heart; another housed a fetal piglet with two perfectly formed heads. Yet another contained what looked disturbingly like a human brain.

Mr. Little stood before the lab table at the head of the classroom. He wore a white lab coat over a collared shirt and a brightly colored necktie printed with the design of a DNA helix. He was a small, energetic man—the literal incarnation of his last name—and he was smiling like the master of ceremonies in a particularly exciting show. His safety goggles, worn over his regular glasses, made his eyes look huge and insectoid.

“Come on in. Find a seat. Don’t be shy,” he said as students filtered into the classroom. “I promise there will be no major explosions or dismemberments. At least not on the first day.” He flashed a naughty grin.

Chris didn’t know everything he would be learning in the class, but he already knew one thing: he had never met a teacher like Mr. Little.

“All right, let’s go ahead and get started,” Mr. Little said, though the tittering among the students didn’t die down. Chris expected Mr. Little to raise his voice, take out his roll book, and start taking attendance, but instead he poured some kind of clear solution into a glass container he held over a Bunsen burner. Within seconds, a huge fireball appeared, its flames falling just short of licking the ceiling, then disappeared instantaneously.

Everybody in the classroom gasped.

“I thought that would get your attention,” Mr. Little said, grinning. “But I promise, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet!” He looked around the room. “This is science! And it is not for the faint of heart or the cowardly. It’s not about just reading a textbook and answering questions correctly. It’s about innovative thinking. It’s about getting your hands dirty. It’s about experimenting, with all that the word experiment implies. Sometimes we succeed, and sometimes we fail, but either way, we learn. In this class, I may ask you to do some stuff that sounds kind of crazy, but I promise that if you bear with me and follow my advice, by the time you’re done with this course, you’ll be thinking, talking, walking, and quacking like a scientist.” He looked around the room. “Now who’s ready to learn some cool stuff?”

Everybody clapped, hooted, or cheered. Chris already felt like he was a member of an exclusive club.

“Now, before we get to the fun stuff, we have to jump through a few bureaucratic hoops,” Mr. Little said, “the first being this lab safety contract, which you and your parents must read and sign, saying that you will not intentionally blow up the school or another classmate.”

“Aw, where’s the fun in that?” a kid in the front row asked, and everybody laughed.

“Oh, it’s always good fun until you have to scrub somebody’s viscera off the walls,” Mr. Little said. “I do hate it when students leave a mess.”

More laughter.

The boy sitting in front of Chris raised his hand and asked, “Are you going to talk about the lock-in?”

“Yes,” Mr. Little said. “There will be a meeting in this room right after school today for everybody who’s interested in coming to the lock-in this weekend. I strongly suggest that you all come both for the sake of your grades”—he mouthed the words extra credit—“and for the sake of science!”

Once class was dismissed, the boy in front of Chris turned around. “I haven’t seen you around before. Are you a freshman?” His brown eyes were intense and intelligent.

“Yes,” Chris said. “How about you?”

“Sophomore,” the boy said. “Sanjeet Patel. Everybody calls me San.”

“Chris Watson.” San radiated not only intelligence but confidence. Chris suddenly, desperately, wanted this kid to like him.

“Are you doing Science Club?” San asked as they gathered their belongings.

“Sure. It’s practically all I’ve thought about since I knew I was coming to West Valley.”

San smiled. “Once you’re in, it’ll still be all you think about. Do you have lunch next period?”

Chris nodded, hoping for a lunch invitation. This conversation seemed to be going well.

“So do I and a lot of Science Club people. Why don’t you sit with us and let everybody get a look at you and see what they think?”

“That would be great. Thanks.” Chris was happy to be included, even if it was seemingly on a trial basis.

In the cafeteria, he sat with San and two other kids—a tall, lanky, red-haired boy who introduced himself as Malcolm, and Brooke, a petite Black girl with springy, dark curls.

“Chris is in Mr. Little’s third-period class with me,” San explained by way of introduction as they settled down to eat their lunches. Chris was the only one of them eating the lunch the cafeteria provided. The others all had packed lunches with fresh fruit and raw vegetables and sandwiches on whole wheat bread. Chris made a mental note to tell his mom that he wanted to start bringing his lunch. He would also have to be specific about what kind of foods to buy and pack. He couldn’t let these kids see him eating peanut butter and jelly on soggy white bread.

“Well, you must be reasonably intelligent, then,” Malcolm said, looking Chris over. “Mr. Little only lets a handful of freshmen into his level-two classes.”

Brooke smiled. “Yeah, the freshmen who don’t make the cut have to take Mrs. Harris’s earth science class.”

“I know, right?” Chris said. Josh and Kyle were in Mrs. Harris’s class.

“Oh, come on, guys. They do lots of really challenging experiments,” Malcolm said, “like mixing vinegar and baking soda to make a volcano.” His voice dripped with sarcasm.

“You’re terrible,” Brooke said, but they all laughed.

“They also collect fall leaves and glue them to construction paper,” Malcolm added. “Though it’s too hard an assignment for most of them.”

Chris laughed some more along with his—he hoped—soon-to-be friends.

San could hardly contain himself. “And their final exam,” he said, laughing so hard he almost couldn’t speak, “is to try to find the school cafeteria.”

“Many fail, of course,” Malcolm said, snickering.

Chris couldn’t remember the last time he had laughed so hard. Of course, he felt a little bad because when he laughed about the stupidity of Mrs. Harris’s students, he was also laughing at Josh and Kyle, who had been his friends since he was old enough to walk and talk.

But he knew if he was going to reach his goals, he couldn’t be sentimental. It was time to move up to a better class of friends.

As soon as the dismissal bell rang, Chris hurried to Mr. Little’s classroom. He couldn’t wait to hear about the lock-in. Other students must have felt the same way because when he got there, the room was nearly full and abuzz with chatter. He found an empty seat near San.

“I wonder what Mr. Little has cooked up this year,” San said to Chris.

Chris smiled. “I don’t know. I hope it’s cool.”

“Oh, it will be,” San answered, as though Chris’s statement implied some kind of doubt in Mr. Little’s abilities. “Until you’ve experienced it, you can’t possibly understand. It will be life-changing.”

Chris nodded. He guessed he didn’t understand, but he was looking forward to learning. And a life-changing experience was exactly what he needed.

“Hey,” San said, “Malcolm and Brooke and I have a study group that meets at Cool Beans Coffee on Wednesdays after school. You should come.”

“Are you sure? Are Malcolm and Brooke okay with it?” Chris asked. He didn’t want to appear pushy, like he was trying to force his way into their friend group.

“Yeah, they suggested it,” San said. “They like you.”

Chris smiled. He could feel his life changing already.

The room fell silent when Mr. Little entered. He walked down an aisle of the classroom like a celebrity walking the red carpet. When he stopped and stood before them, he said, “Greetings, my sweet little guinea pigs! Are you ready to hear what kind of experience I have planned for this weekend?”

The students clapped and hooted. Chris wasn’t used to seeing such displays of enthusiasm in a classroom. It was a refreshing change.

“First of all,” Mr. Little said, starting to pace, “science requires sacrifice. If you’re not willing to make a sacrifice, to give up a part of yourself for the sake of science, then don’t bother coming in on Friday because this lock-in isn’t for you. Stay home and do whatever it is you do on your little electronic devices or go play a sport or whatever. Only come here if you are willing to make a sacrifice and experience a transformation.”

Transformation. Chris felt like that was the word he had been looking for to describe what he was seeking. He wanted to transform his life, to transform himself, into something different, better, more worthy.

“In the past, some of our Science Club lock-ins have been group activities. This activity is one you will do alone. In fact, each of you will have a cubicle sequestering you from the other students and from me as well. Each of you will be issued your own Freddy Fazbear Mad Scientist Kit to work with. In this kit, you will find a solution called Faz-Goo. You will put the required amount of Faz-Goo in the provided petri dish.” He smiled. “Then comes time for the sacrifice. With the pliers I will provide, you will pull one of your teeth—”

A gasp rose from the crowd. Chris heard himself gasp, too. One of their teeth? Surely he hadn’t heard Mr. Little correctly.

“Excuse me, Mr. Little, could you repeat that part?” one student asked in a nervous-sounding voice.

“Teeth!” Mr. Little yelled. “You will pull one of your teeth! It might hurt a little, but trust me … it will be worth it in the end. Now, are you scientists, or are you a bunch of sniveling babies?”

“Scientists!” most students yelled back.

“Good.” Mr. Little resumed his pacing. “So you will pull one of your teeth, as I said, and you will place it in the Faz-Goo. Then you’ll do what scientists spend a great deal of their time doing. You will wait. You will be provided with a cot to nap on while the process unfolds.”

“And what process is that?” one student asked.

“Well, what fun would it be if I told you that? All I’ll say is that it is the process of discovery!” Mr. Little’s eyes were wild with excitement. “You will know when you’re done because the results will speak for themselves. Literally. Then you will dispose of your creation in a biohazard bag and leave, a changed person. And not just dentally, but mentally!” He cackled at his own joke, and many students joined in on the laughter.

“There is a rumor,” Dr. Little said, “that not participating in the lock-in hurts your performance in my classes. This is not exactly true. If you do not participate in the lock-in but you successfully complete all course requirements, you will still pass my class, possibly with an above-average grade. However, over the years I have found that the students who do participate in the lock-in demonstrate a level of commitment that allows them not just to pass, but to excel. And the fact that the lock-in is worth five hundred points of extra credit doesn’t hurt, either.” He grabbed a stack of papers off his desk. “Now for those of you who are up for this challenge, I will now distribute the required parental permission sheets that allow you to participate in the lock-in. But please, make sure you don’t say anything to your parents about the required tooth extraction. I don’t want to be on the receiving end of any dental bills. Also, as a community of scientists, we must keep our secrets.”

Chris felt excited but also scared. He wouldn’t let his fear stop him, though. You didn’t transform yourself by playing it safe. You had to take risks, try new things.

When Dr. Little offered him a permission sheet, he grabbed it.

There was only one part of the lock-in that Chris dreaded. The more he had thought about it, the more nervous he became at the prospect of pulling out one of his own teeth. Chris had always been squeamish about dental matters. When he was little and had a loose baby tooth, he would procrastinate pulling it until the tooth hung by the smallest of threads. Sometimes, if he was lucky, the tooth would just come out without him even having to touch it. He lost one in an apple once, another in an ear of corn. Another time, when he had one tooth that he had been letting hang on for a number of weeks, his dad asked to see it, then yanked it out without warning. Chris had been mad at him for days.

Then there was the matter of dental visits. Even if it was just an exam and a cleaning, Chris was consumed with anxiety for weeks before. His mother told him she loathed his trips to the dentist as much as he did because she was the one who had to get him there and put up with his moaning and groaning before, during, and after.

Chris lay awake all night thinking. The lock-in was two nights away. If he could just figure out a way to participate in the experiment without having to pull his own tooth …

“Chris! Your friends are at the door!” his mom called.

Again? Chris thought. It showed how much less serious Josh and Kyle were that they’d show up and want to hang out on a school night. “Tell them I have homework!” Chris yelled.

“Come tell them yourself!” his mom yelled back.

Chris rolled his eyes but got up from the bed. He went to the door to see Josh and Kyle. “Hey,” he said, “I can’t hang out tonight. I’ve got homework.”

“We just stopped by for a sec,” Josh said. “Kyle’s mom is going to drive us to the mall on Friday. We’re going to eat at the food court and see the new Revengers movie. We wondered if you wanted to come.”

It was kind of them to ask, but their pastimes seemed so childish now. “Thanks, guys. I’d love to, but I’ve got the Science Club lock-in that night.”

“Oh, you’re doing that?” Kyle said, sounding incredulous. “It seems kind of sad to spend most of a weekend in school.”

“Well, I think it’s exciting,” Chris said.

Kyle and Josh exchanged a look.

“Just don’t get too deep into the Science Club stuff, okay?” Josh said. “Some people in Mrs. Harris’s class were talking about it yesterday. They say it’s weird, like a cult or something.”

Chris couldn’t help but be offended. Josh and Kyle might not be cut out for Science Club themselves, but they could at least show it the proper respect. “Well, people in Science Club talk about the people in Mrs. Harris’s class, too,” Chris said.

“Yeah,” Kyle said. “They say we’re dumb.”

“Because they’re snobs,” Josh added.

Kyle gave Chris a strange look. “You’re not turning into a snob, are you, Chris?”

“No, of course not,” Chris said. He hated that word, snob. It was what underachievers called high achievers to try to make them feel better about themselves. Well, he refused to take the bait.

“Do you think Josh and me are dumb?” Kyle asked.

Chris cringed a little. It’s “Josh and I,” he thought reflexively. And you’re not dumb; you just lack maturity and ambition. But he figured it would be a bad idea to say either of those things out loud.

“No, of course not,” Chris said again. “Look, guys, I’ve got to get back to my homework. Maybe we can do something next Friday, okay?”

They said “Sure” and “Okay,” but Chris could feel the distance between him and his old friends growing. It was a painful transition, but it was probably for the best.

“Bye, guys,” Chris said and shut the door.

In the living room, Chris’s mom was leaning over Emma, who was sitting on the couch.

“Count to three out loud before you do it, okay?” Emma said.

“Before you do what?” Chris asked.

His mom looked over at him. “Emma’s got a loose tooth. I’m going to pull it for her.”

Chris felt his stomach lurch. “Well, don’t do it while I’m in here! You know that stuff grosses me out.” Why couldn’t his family tend to distasteful matters in private instead of in the middle of the living room? It was just a sign of how unrefined they were.

Mom laughed. “Wait till you’re a parent. None of the stuff that grossed you out as a kid will bother you anymore.”

Chris shook his head. “I don’t know about that. If I have a kid, he’ll definitely have to pull his own loose teeth.” Chris fled the scene of the tooth extraction and went back to his room. As soon as he was alone, his thoughts turned to the Science Club lock-in. The idea hit him like a jolt of electricity.

Loose tooth. Of course! That’s the answer.

Chris had walked past Cool Beans Coffee probably thousands of times, but he had never gone inside. For some reason, it just hadn’t felt like it was for him. It was too sophisticated and adult, full of professionally dressed grown-ups sitting with their laptops and cardboard cups.

But today that was going to change. Chris was going inside.

He swung the door open and was immediately greeted by the dark, toasty smell of coffee. Paintings by local artists hung from the café’s redbrick walls. Chris had to tell himself not to be nervous, that from now on this was the kind of place where he belonged.

“Hi, Chris!” San waved at him from where he and Malcolm and Brooke were sitting, their table strewn with open textbooks, notebooks, and coffee cups. “Get a drink and join us.”

“Great! I will!” Chris called back. He studied the menu board over the counter. It was more confusing than anything he had ever studied in a class. There were mochas and frappes and cappuccinos and lattes. There were single shots and double shots and decaf and half-caff. Chris had never taken so much as a sip of coffee before, and he had no idea what any of these words meant.

The pretty young woman at the counter said, “May I help you?”

“Sure, I’m just not a very experienced coffee drinker, so I don’t really know what I want.”

She smiled. “How about if I just make you something I think you’ll like?”

Chris was relieved to have the responsibility out of his hands. “Sure.”

“Do you like chocolate?”

“Of course. I’m not stupid.” What kind of weirdo didn’t like chocolate? Chris thought.

She smiled again. “Let’s try an iced mocha, then. Give me just a couple of minutes.”

She turned her back on him and poured some different syrups in a machine. Chris couldn’t decide if her actions looked more like chemistry or wizardry. Shortly after, she returned with a huge, clear plastic cup filled with what appeared to be rich chocolate milk topped with whipped cream and chocolate shavings. It looked like the world’s fanciest milkshake.

The price she quoted was two dollars more than he expected, and he hoped his new friends didn’t see him having to dig through his pockets and his backpack for change.

He took his expensive beverage and joined San, Malcolm, and Brooke at their table. They were all drinking hot coffee from paper cups, and compared to theirs, his milkshake-like drink looked childish. He had to admit it was delicious, though.

“So it looks like we’re going to France this winter break … again,” Malcolm was saying. “I really wanted to do Italy, but my mom can’t pass up the shopping in Paris. I’m going to be bored to tears.”

“I think we’re doing a Caribbean cruise this year. I guess it’ll be okay,” San said. He turned to Chris. “We were just talking about family vacations and how we never get any say in where we go.”

“Same here,” Chris said. He hoped they didn’t ask him about where his family had gone on vacation. Chris’s family vacations were always the same. His parents took a week off in the middle of the summer, and they rented a cabin at a state park that was a couple of hours away. They spent the week fishing, swimming, hiking, and cooking out. It was always hot and buggy. For the most part, they had fun, but Chris knew it was a poor people’s vacation.

“Ooh, that looks good,” Brooke said, nodding toward his drink. “Is that a mocha?”

“Yes,” said Chris. He was going to have to study up on coffee lingo. His parents drank coffee, but just the kind you bought at the grocery store and made at home.

“Mine is, too,” she said. “Just hot instead of iced.”

Chris felt less self-conscious about his drink now. You need to loosen up around your new friends, he ordered himself. They had invited him to join them. They wanted him here. It was time for him to start acting like he belonged.

“So what kind of results do you think the experiment at the lock-in will produce?” San asked, looking around the table.

“Well, clearly we’ll be growing some kind of tissue,” Malcolm said, sipping his coffee. “I just don’t know what it will do.”

“It’ll do something, though, that’s for sure,” Brooke said. “Hopefully nobody will end up in the emergency room like last year.”

Chris almost choked on his coffee. “Wait, what?”

Brooke laughed. “Some kid didn’t follow the instructions right and ended up having to have a couple of fingers reattached. It was his own fault, though. He ended up transferring to Mrs. Harris’s science class, where he was less likely to maim himself.”

“The experiments are always perfectly safe if you know what you’re doing, but that kid clearly didn’t,” Malcolm said. “Speaking of knowing what we’re doing, if we’re calling ourselves a study group, we’d better get down to studying.”

Chris was usually already home when his mom came in from work, but today she beat him there.

“There you are,” she said when he came in. “I signed your permission slip for the school thing. I was worried when I didn’t see you here. I was just about to call and check on you.” She was sitting on the couch with a glass of iced tea, her bare feet propped up on the coffee table. She didn’t move, but extended a hand with the paper.

“I’ve joined a study group that meets after school,” Chris said, pocketing the slip.

His mom laughed. “If some other kid told me that, I might think he was lying so he could run around after school doing who knows what. But I believe you.”

“I know I’m a nerd,” Chris said, sitting beside his mom on the couch.

“I’m proud you’re a nerd,” she said, smiling.

“I was wondering,” Chris said, “might it be possible for me to have a small increase in my allowance?”

Mom took her feet off the coffee table and sat up straighter. “How much are we talking?”

Chris tried to calculate a figure that wasn’t too outrageous but still would cover the price of expensive coffee drinks at study group meetings. “Ten dollars?”

Mom furrowed her brow and made a low whistling sound. “And what do you need ten more dollars a week for?”

“It’s this study group, actually. We meet at Cool Beans downtown, and I need money for coffee.”

“Gotten hooked on the stuff already?” his mom said, shaking her head. “Listen, kid, those froufrou coffee drinks are real money suckers. One gal I work with used to buy one every day, and when she quit the stuff, she was amazed how much money she saved.”

The fact that she was lecturing him was not promising.

“Why can’t you guys study at the library?” his mom asked. “The library is free.”

Chris felt a wave of annoyance sweep over him. “Mom, I didn’t start the study group; I just joined it.”

“Well, maybe you could suggest meeting in the library. I’m sure it would save everybody a lot of money.”

Chris rolled his eyes. “If I suggest that, they’ll think I’m poor. Which I am, compared to them.”

His mom sighed. “If they’re your friends, they don’t care how much money you have, and you shouldn’t care how much they have, either.”

“Mom,” Chris said, on the verge of losing his temper, “that’s not the way the world works.”

She sighed. “I know it’s not. I wish it was, though.” She looked at Chris with a sad little smile. “Okay, I can give you five more bucks a week, but that’s all. I’m glad you’re making friends who take school seriously. Study hard so you can get rich and support me in my old age.”

“Thanks, Mom,” Chris said. This time, he didn’t object when she gave him a hug.

Chris was buzzing with excitement as he walked to Mr. Little’s classroom after school on Friday. He knew the lock-in was going to be a transformative experience, probably the most important experience in his life to date. He hoped he could complete the experiment to Mr. Little’s satisfaction and gain his approval as well as the approval of the other Science Club members.

Chris wasn’t the only student who was excited. As he entered the classroom, he could feel the high level of energy. It felt electric. Everybody was talking and laughing. Some people stood and paced instead of sitting at their desks, too restless to sit still. Chris took his usual seat behind San.

San turned around and grinned at him. “Your first lock-in. This is a big day for you, right?”

“Yeah,” Chris said, smiling back.

“It is for me, too,” San said. “But it’s even bigger for you because it’s your first time. After tonight, you’ll be a full-fledged member of Science Club!”

“All eyes on me, all mouths closed,” Mr. Little called from the head of the classroom. “I know you’re excited—heck, I’m excited, too!—but there are some very important directions you have to follow exactly, or the experiment won’t work.” He pushed his glasses up on his nose. “I have also taken the liberty of ordering some pizzas, which should be here shortly.”

Cheers rose from all over the classroom.

“It’s going to be a long night, and you should never conduct scientific research on an empty stomach. But while we wait for sustenance, allow me to explain more specifically what you’ll be doing tonight. As you can see, I have set up private cubicles for each of you in the lab. In your cubicle you will find a long table and a cot for napping. On the table, you will find a Freddy Fazbear Mad Scientist Kit.”

There were a few chuckles in the class, and one kid said, “But isn’t that kit just a toy?”

“It is most definitely not a toy,” Mr. Little replied, his voice turning stern suddenly, “and if you treat it as one, it will be at your own peril.” He held up the kit for everyone to see and then opened it. “In the kit you will find a container of Faz-Goo and a petri dish, like this.” He held up a vial of pink glop and a small dish. “You will empty the Faz-Goo into the petri dish. Then comes the sacrifice.”

“The tooth,” Chris half whispered.

“Yes, the tooth!” Mr. Little said, grinning wildly. “You will use the pliers”—he held up a pair of pliers—“to extract the tooth of your choice. I would advise one near the back. When your wisdom teeth come in, you won’t have to worry about crowding.”

Chris heard a sharp intake of breath from someone behind him. All of a sudden, his stomach felt queasy at the thought of the tooth extraction. He was glad he had figured out a way around it.

“If you can’t handle this part of the experiment, now is the time to leave.” Mr. Little looked around the classroom. “It’s time to separate the real scientists from the wannabes.”

Chris looked around the room. Some kids looked scared, but none of them moved.

“Good,” Mr. Little said, nodding in approval. “I like my students to be fully committed. After you have extracted the tooth, you will place it in the petri dish of Faz-Goo. And that,” he said, rubbing his hands together, “is when things start to get interesting. You see, the Faz-Goo will not only make the tooth stay alive … it will make the tooth believe it is still a part of you.”

“A tooth can believe something?” Brooke asked.

“Well, it can feel that it’s still inside your mouth,” Mr. Little said. “The Faz-Goo is very powerful. When you touch it, it creates a tendril—a connection—that slowly pulls red blood cells from your body. The blood cells feed the Faz-Goo and fuel the experiment. And here’s the amazing part: Over the course of several hours, nourished by just a few of your red blood cells, the tooth will grow gums, will form a full mouth, and that mouth will open up and tell you something that I promise, no matter how old you live to be, you will never forget.”

Chris looked around at his classmates, all of whom were wearing an identical look of disbelief.

“You’ll see,” Mr. Little said, looking around at all the stunned faces. “It will be amazing. Once the mouth has told you what you need to know, it will die. I have provided a biohazard bag in each cubicle. You will dispose of the mouth and the Faz-Goo in the bag. After you have brought me the bag so I can dispose of it correctly, you are free to go.” Mr. Little looked toward the classroom door and smiled. “But first, pizza!” He waved for the pizza delivery guy to come in. “You have thirty minutes to eat, drink, and socialize,” Mr. Little said. “But after that, it’s time to get to work!”

Chris grabbed a couple of cheese slices and a paper cup of soda and sat down with San, Brooke, and Malcolm.

“I guess this will be the last pizza I chew with my left back molar,” Malcolm said, but he sounded more amused than scared.

“I’m a little worried pulling one of my teeth will mess up my orthodontia,” Brooke, who had a mouthful of braces, said.

“Yeah, your orthodontist is going to be mad,” San said. “Will your parents be mad, too, when they find out?”

Brooke shrugged. “Not if I tell them it was a Science Club assignment. They’d let me saw off my own arm if they thought it would improve my chances of getting into a good college.”

“My parents would, too,” Malcolm said, and they all laughed. “They’d let me saw off both arms if it would get me into the Ivy League.”

“My mom will definitely be mad,” San said.

Brooke laughed. “Oh, she will, won’t she? I forgot!”

“Forgot what?” Chris said.

Brooke laughed some more but managed to get out, “San’s mom is a dentist!”

After they laughed some more, Malcolm said, “That reminds me, Chris. I don’t believe you said what your parents do for a living.”

Chris felt a flutter of panic in his belly. He couldn’t possibly tell them that his mom was a cashier where people paid their electric bills and that his dad fixed people’s cars. “Um … my mom is an electrical engineer, and my dad is a mechanical engineer.”

“Wow, two engineers for parents!” San said. “You must be really good at math.”

Chris nodded. This part, at least, was true.

“Okay,” Mr. Little called. “Time to get to work, scientists!”

Chris was glad that he hadn’t revealed to San, Malcolm, and Brooke that he was going to perform the experiment without having to pull his own tooth. He couldn’t let anybody know that he had figured out a way to game the system.

Chris entered his cubicle and filled the petri dish with Faz-Goo as instructed. Within a couple of minutes, he could hear grunts and groans as the students in the other cubicles labored to pull out their teeth. In the cubicle nearest him, he heard a scream, followed by a sickening popping sound as the tooth released from its root.

Chris figured that for the sake of realism, he should grunt and groan a little, too. He faked it for a few minutes, very believably, he thought, and then he reached into his pocket and pulled out his ace in the hole.

The sight of his mom about to pull his sister’s tooth the other night had made him remember that when he was little, he had declined money from the Tooth Fairy in order to keep all his old baby teeth. He didn’t know why he hadn’t been willing to let them go, especially for cash, which was hard to come by in his family. He had been a weird little kid. But now that weirdness was paying off.

Chris submerged his old baby tooth in the Faz-Goo. When he touched the goo, he thought he felt a slight sucking sensation in his fingertips. He pulled his hand away, but a tendril of pink slime connected his index finger to the petri dish with his tooth in it. The tendril was stretchy, like mozzarella cheese when you lift the first slice from a hot pizza.

Now there was nothing to do but wait for the tooth to get what it needed from him. He lay down on the cot, making sure not to break the tendril that connected his finger and the Faz-Goo.

Chris closed his eyes and let himself doze. Soon he was dreaming of future successes. He saw himself as though he were a character in a movie, opening the letter granting him a full scholarship to an Ivy League university. He saw himself doing research in a lab at the university. The lab was bright and clean and filled with the most cutting-edge equipment. A distinguished professor in a white lab coat stood behind him and looked over his shoulder, smiling at the good work he was doing. Chris saw himself in a black cap and gown, walking across a stage. The university professor handed Chris his diploma, and Chris smiled to have his picture taken.

But when Chris smiled, it was immediately clear that something was wrong. Blood dripped from his lower lip down his chin. His mouth was a black cavern framed by a bloody mess of gums.

Somebody had pulled all of Chris’s teeth.

Chris startled awake. He was disoriented at first, waking up on a narrow cot in a cubicle, but then he saw the tendril strung between his finger and the petri dish and remembered where he was and why.

Sitting up, Chris heard movement and whispering coming from the other cubicles. Could the whispering be coming from the mouth that this experiment was supposed to create? Chris pressed his ear to the partition in hopes of making out what was being said, but no words were discernable. From where he was, the whispering just sounded like the soft whooshing of wind through trees.

But then he heard the voice of the student in the cubicle next to his.

“Wow,” she said, her voice filled with awe. “Wow.”

There was a rattle of plastic, which could have been the biohazard bag, then the sound of footsteps. Chris pushed one of his cubicle’s partitions open just a crack so he could watch the student leave.

It was Brooke, but the look on her face was different than her usual smart, collected expression. Somehow her features seemed softer, more open. Her eyes were wide and full of wonder. She walked up to Mr. Little and handed him the biohazard bag.

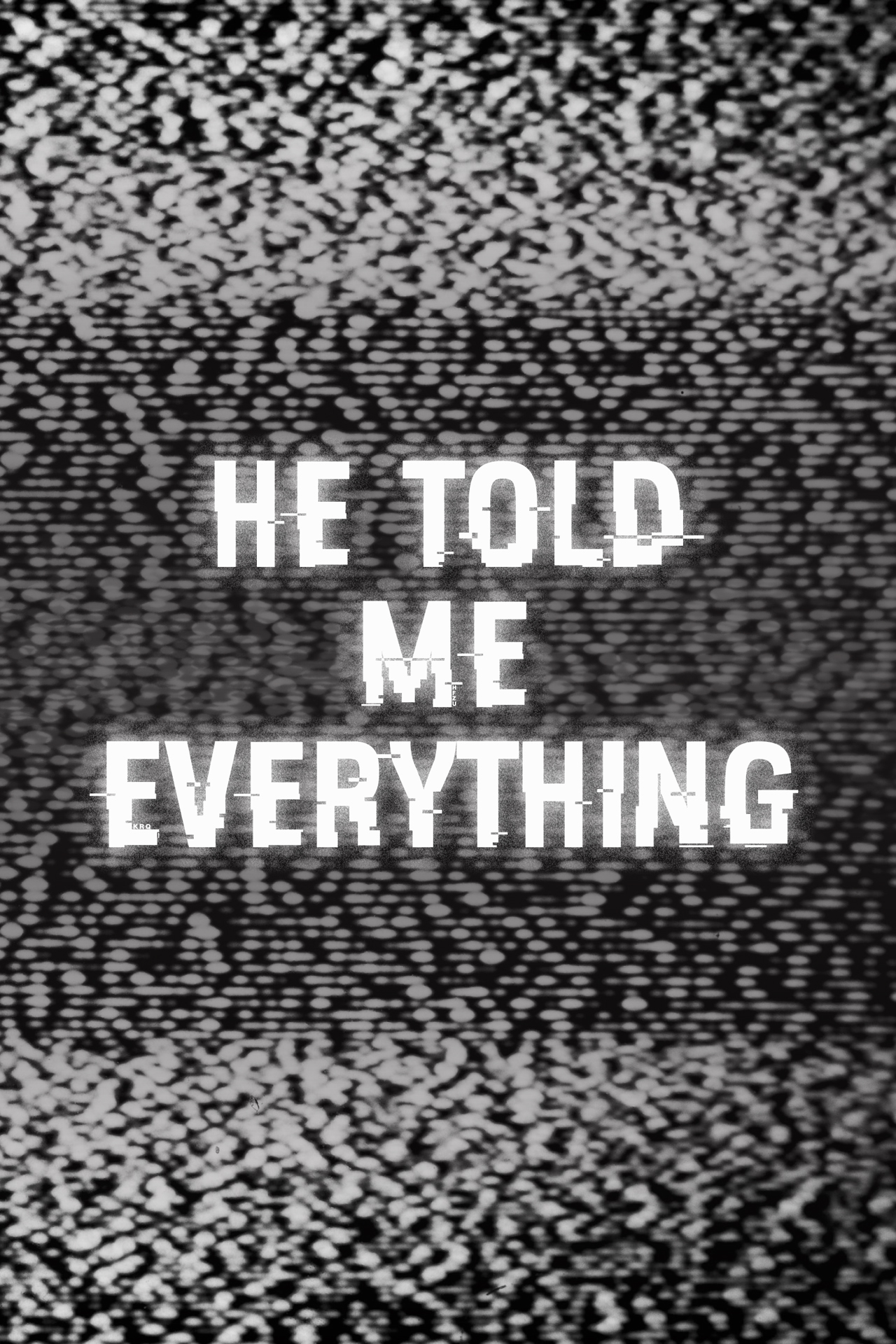

Brooke rested her hand on Mr. Little’s forearm and looked him in the eyes. “She told me everything,” Brooke said.

Mr. Little smiled. “Good. Nice work, Brooke. You’re free to go.”

Brooke smiled back at Mr. Little and wandered toward the door.

Chris was just about to close the small opening in the partition when he saw another student, a tall, dark-haired boy he hadn’t met yet, emerge from a cubicle across the classroom. Just like Brooke, he wore an expression of amazement. He walked up to Mr. Little and handed him the biohazard bag.

“He told me everything,” the boy said, placing his hand on Mr. Little’s shoulder.

Mr. Little smiled and nodded. “Good. Nice work, Jacob. You’re free to go.”

“Thank you,” the boy said, as though Mr. Little had just given him a gift.

Chris closed off the partition. Clearly, the experiment was starting to work for some people, but when he checked the progress in his petri dish, he couldn’t see any significant change. It was still just his old baby tooth submerged in a puddle of Faz-Goo.

What if my experiment doesn’t work? Chris wondered. What if I fail?

Ever since middle school, when his class visited the high school science fair and Chris saw the amazing experiments conducted by Mr. Little’s students, Chris had dreamed of being in Science Club. What if he didn’t belong there? What if he lacked the necessary knowledge and skill? So many of the Science Club kids were the sons and daughters of scientists themselves, or of doctors or lawyers or college professors. Chris was the son of a clerk and a laborer. Maybe he wasn’t of the right stock to make the grade in this intellectual environment.

Suddenly Chris felt drained, depleted. Maybe this meant the Faz-Goo was draining him of the energy it needed to make the experiment work. Or maybe it was just the feeling of him giving up hope. Either way, he was exhausted. He lay down on the cot again and fell asleep instantly.

Chris woke up groggy with his face in a puddle of his own drool. His surroundings were strangely quiet—no whispering, no sounds of movement. He sat up and wiped away the drool. The tendril on his index finger reminded him to check his experiment’s progress. Maybe it was finally working. He tried to muster up some hope.

The goo had outgrown the petri dish. It didn’t look like a mouth or much of anything else, really. It was a pink blob, slimy and unpleasant, about the size of a baby’s fist.

It was something, anyway. He just wasn’t sure what.

Around him, the room was still quiet. Had everybody else left?

After a few seconds, Chris heard rustling, then footsteps, then a voice saying, “He told me everything,” followed by Mr. Little’s praise and permission for the student to go.

Chris sighed and sat on the cot and waited. He watched the mass in the petri dish, but if there was any progress, it was too slow to see. It was akin to watching paint dry or grass grow.

“Permission to enter?” a voice said from outside the partition.

“Sure,” Chris said.

Mr. Little stepped into the cubicle. “How’s it going, Chris?”

“Uh … I’m not sure, to be honest. Am I the last person left?”

Mr. Little smiled. “No, there are a few other stragglers. I’m just making the rounds and checking up on everybody’s progress.” He nodded in the direction of the table. “May I?”

“Of course.” Chris felt nervous for Mr. Little to look at his nowhere-near-finished project.

Mr. Little approached the table and looked at the blob, cocking his head in a way that reminded Chris of the family dog. “Hmm,” Mr. Little said, leaning down and squinting over the petri dish. “Very curious.”

“Did I do something wrong?” Chris asked. He knew where he had gone wrong, even though he wouldn’t admit it to Mr. Little. He should have followed directions and pulled out one of his own teeth on the spot like the rest of the students did. He had taken the easy way out because he was a coward, and now he was reaping the consequences.

“As experiments go, this one is pretty impossible to mess up,” Mr. Little said, rubbing his chin. “You did put one of your teeth in there, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir,” Chris said, not elaborating on the age or origin of the tooth.

“Well, sometimes in science we just have to admit that we don’t know why things are happening as they are. The way I see it, Chris, you’ve got two choices. You can end the experiment and say it just didn’t turn out for whatever reason, dispose of whatever that thing is that you’ve got there, and go home and play video games or whatever it is you do on your own time.” He smiled. “Or you can acknowledge that something interesting is happening here, even if we don’t quite know what it is, and give it some more time to see what happens.”

Chris didn’t have to ask himself which choice a real scientist would make. “I’d like to give it some more time if that’s okay.”

Mr. Little smiled and clapped him on the back. “It’s more than okay! I admire your patience. It’s an excellent quality for a scientist to have. Most scientific endeavors worth doing require a great deal of patience and determination.” He looked back at the blob. “And to be honest, I’m glad you made that choice because I’m pretty curious to see how this turns out myself.” He gave Chris a little two-fingered salute. “I’ll check back later, okay?”

“Okay. Thank you, sir.”

Chris felt relieved. He had made the right choice, and he had received Mr. Little’s approval. Maybe he could be a real Science Club member after all. He sat down to wait because that’s what scientists did.

After a while, there was more movement and rustling, followed by similar words uttered by different voices:

“He told me everything.”

“She told me everything.”

“He told me everything.”

Each time, there was Mr. Little’s approval for the student to leave.

And then there was silence.

Finally, feeling like the last person on earth, Chris called, “Mr. Little?”

“Yes, Chris?”

“Am I the only one left?”

“You are.” His tone was pleasant. “No worries, though.”

“Should I give up so you can go home?” Chris wondered if Mr. Little had a wife and some little Littles waiting on him, wondering why the lock-in was taking so long.

Mr. Little poked his head inside the cubicle. “Of course not! I’ve got no place else to be, and if you’re willing to wait, so am I.” He grinned and gave a thumbs-up. “Patience and determination.”

Once Mr. Little had disappeared from view, Chris felt another wave of exhaustion. Hoping that the energy draining from him was being funneled into the little pink blob, he lay back down on the cot and lost consciousness immediately.

When he awoke, he gasped at the sight on the table. The mass had more than quintupled in size and was now far too large to fit into the biohazard bag. It was still slimy and pink, but it was no longer an inert blob. Shaped somewhat like a limbless human torso, it was now pulsing with life.

Chris felt excited but also a little fearful as he approached his creation. The way it expanded and contracted made him feel like something might jump out of it like a creature he saw in a horror movie once.

He stood over the pulsing mass. Its skin, if you could call it that, was a translucent pink, like a bubble blown from bubble gum. Beneath it was the source of the pulsing, a cluster of baglike structures that were beating to a rhythm that seemed strangely familiar, though Chris didn’t know why.

Chris looked at the tendril, now thicker and stronger, that connected him to the newly formed organism on the table. The tendril pulsed in unison with the strange thing’s organs. Chris gasped when he realized why the pattern of this pulsing seemed so familiar.

The thing’s organs and the tendril that connected him to it were throbbing with the beat of Chris’s own heart.

A shudder ran through him, and he was overcome with a sudden need to empty his bladder. Now that he thought about it, he realized he hadn’t gone to the bathroom for hours, not since right after the school dismissal bell rang. This knowledge increased his sense of urgency.

But how could he manage to go down the hall to the boys’ restroom when he was physically connected to this big, weird, seemingly living thing? He wondered how the other kids had managed it. They probably hadn’t needed to go in the first place because they had completed the experiment so much more quickly than he had. Plus, their experiments hadn’t yielded something so large and unwieldy.

Just as Chris decided that he was desperate enough to call for Mr. Little and make the pathetic confession that he needed to use the restroom but didn’t know how, the pressure in his bladder disappeared. He looked over at the thing on the table, which expelled a large amount of fluid that hit the floor with a splash.

Was that his pee? And what was it doing over there?

Chris knew he should have been embarrassed—he was pretty sure he had just peed on the floor of his science classroom, after all, a big no-no if there ever was one—but mostly he was just confused. Wasn’t his pee supposed to come out of his own body? He looked at the tendril. Now even thicker and stronger, it was a tube connecting his body to the thing, feeding it like the umbilical cord that connects a mother with her unborn baby. Maybe his pee had traveled from him through the tube to be expelled by the thing on the table? But why?

He watched the thing pulse some more. Whatever it was, he didn’t like it, and he didn’t like being connected to it. He didn’t like knowing he was letting it leech his energy so it could grow bigger and stronger while he grew more exhausted and weak.

It was time to cut the cord.

The problem was … he didn’t have anything to cut it with.

He looked around the almost-empty cubicle and spotted the unused pliers. They weren’t as good as a knife or a strong pair of scissors, but they were still better than trying to sever the cord with his bare hands. He would use the pliers to grip and squeeze the cord, then give it a hard yank to tear it apart and break the connection.

He poised the pliers to grab the tendril just above where it connected with his left index finger. Then he squeezed.

It felt like somebody was choking the life out of him. Pinching the tube cut off his air supply somehow, and he fell to the floor gasping, landing in a puddle of what was most certainly his own urine. He released the tendril from the pliers, and his breath started to come back. He was too light-headed to get up quickly, so he lay on the wet floor for a few minutes, panting like an overheated dog.

Was there no way to end the connection between him and the disturbing result of his experiment? Or were he and his creation bound together like conjoined twins who shared a vital organ?

He pulled himself up and willed himself to look at the mass on the table. The torso had lengthened, and small pink buds were visible where the arms and legs should have been. Somehow, while he hadn’t been watching it, a neck and a head had formed.

The head was hairless, featureless, horrifying.

Chris backed away slowly, bumping into the cot. He didn’t want to look at the thing anymore, but he couldn’t look away, either. It radiated a horrible fascination, like a gory accident on the side of the highway. He sat on the cot and looked at it until he realized his vision had become blurry and indistinct. It was strange. He had never had trouble with his eyes before.

He put his hand over his right eye, and suddenly it was like the world had been plunged into blackness. He reached up to put his hand over his left eye, and what he found there made him cry out in terror.

His left eye was gone.

It was impossible, of course. The loss of red blood cells and his level of anxiety must have been disrupting his perceptions, making him paranoid, maybe even making him hallucinate. He reached up for his left eye again, but felt only the gaping, empty socket.

Impossible, he told himself again, but then he looked at the tendril. Inside the translucent tube, an orb traveled away from Chris and toward the evolving pink form on the table. The orb was being pushed along by the tendril’s pulsations. It was the size and shape of a human eyeball.

What the—

Chris’s hand shot up to where his eyeball used to be. There was a popping sound, like a cork being pulled from a bottle, and when Chris looked over at the thing on the table, it was looking back at him with Chris’s left eye. The face was no longer featureless. It was now cycloptic.

Chris knew the creature wouldn’t be content to stay a cyclops for long. It would be coming for his other eye. And for more parts of him as well.

Even without the benefit of having both of his eyes, Chris could see things clearly now. The organs that throbbed beneath the creature’s translucent skin were his organs. Or they used to be.

He was being used as a living organ donor for this thing.

But he wouldn’t be a living donor for much longer. With his vital organs being siphoned through the tube one by one, he couldn’t have much time left.

Chris pulled on the tendril, trying to rip it from his body. But it was connected as solidly as his fingers were to his hand, and gripping the tube constricted it and made him lose his breath. He tried to get up, with a vague, hopeless thought of running to where he could get help, even if it meant dragging the thing behind him like a broken kite on a string. But he found himself too weak to stand.

But he still had his voice, didn’t he?

There was nothing to do but scream.

“Help!” he yelled with a voice that was thinner and weaker than he would have liked it to be. “Help! Mr. Little! Anybody! I’m over here! Help me!”

His cries for help were met with silence. Now that all the other students had gone home, had Mr. Little gone home, too? Would he have left without saying good-bye, without giving Chris permission to leave as well?

Chris could not remember ever having felt so utterly alone.

The yelling had tired him out. Everything tired him out. His muscles felt nonexistent, and his arms and legs were as floppy as overcooked noodles. He sank down on the cot. He needed to think of a plan, a way to escape, but weakness and fatigue overtook him. He didn’t mean to fall asleep, but he wasn’t strong enough to fight the wave of exhaustion that swept over him.

When he awoke, he opened his one eye and saw the thing sitting on the edge of the table across from him.

Except it wasn’t just a thing anymore. It was a boy—a boy who, except for a strangely pink skin tone—looked exactly like Chris. It was Chris’s height and build, with his sandy-brown hair. It was wearing Chris’s clothes and looking at Chris with what had once been his left eye.

Did that mean Chris was naked? He looked down at his reclining body and quickly saw that it didn’t have enough structural integrity to support clothes. Chris’s body was devoid of muscles and bone. He was a mass, a blob. He had no idea how he could still be alive, how he could still be aware with so little of him left. There was no way he could hold out much longer.

Chris understood that he would never see his mom and dad and Emma again. He would never take another bike ride to the Dairy Bar and the lake with Josh and Kyle. Somebody else would have to take Porkchop for his walks and feed him his dinner.

The thing got down from the table and used Chris’s bones and muscles to walk over to the cot.

With his one remaining eye, Chris saw his creation. He saw that this creature looked so much like him that nobody would ever know the difference. It would go to Chris’s house and take its place in Chris’s family. It would sit at the dinner table with his mom and dad and Emma, eating hot dogs and macaroni and cheese. It would play with Porkchop. It would study at Cool Beans Coffee and go to school and Science Club meetings.

Chris saw that his own life was going to go on without him.

Chris struggled to speak. His throat and mouth were as parched as a desert, and he was pretty sure his lips were gone. It was hard to make himself heard.

“Listen.” His voice finally came out as a croak. “My mom and dad—they’re going to love you because they love me. Be nice to them.” He stopped to try to catch his breath. Breathing used to be so easy he never even thought about it. “Be nice to my sister, too. She’s a good kid. A Girl Scout. She’s your sister now.” The words were hard to get out, but he had more he needed to say. “Mrs. Thomas, our neighbor. She’s old. She’s a nice lady. Help her when you can. And play with Porkchop.”

The creature furrowed its brow, looking confused. “I am to play … with a porkchop?”

Chris felt the last of his strength fading. He whispered, “Porkchop is my dog. Yours … now.” Chris felt the tendril that connected him to his life disintegrating. “Take care of him,” he said, but his words came out so softly he was afraid that only he could hear them.

Chris felt a strange sensation of suction where his right eye was, and then everything went black. He listened as his eyeball was sucked through the tube. There were more slurping sounds, too, as other parts of him were drawn up through the tendril. Parts he knew he couldn’t live without. It was like the creature was drinking him, sucking the last of his organs through a long straw, like the dregs of a milkshake, leaving only an empty vessel.

Chris, as the creature would have to learn to call itself, stood over the shapeless mass of empty flesh on the cot. He opened the biohazard bag and stuffed the fleshy remains of the experiment inside of it. He was surprised that he was able to cram all of it into one bag, and when he picked it up, the contents were surprisingly light.

It left the cubicle and found Mr. Little sitting at his desk drinking from a Styrofoam cup of coffee and munching on a doughnut. “Well, good morning, Chris!” Mr. Little said, standing up and brushing crumbs from his mustache. “You had a long night, didn’t you? But don’t keep me in suspense. Did you finally complete the experiment? Did you get the results you wanted?”

The new Chris’s eyes were wide and full of wonder. Soon he would be stepping out of the classroom and out of the school and into the world for the first time.

Chris handed the biohazard bag to Mr. Little. He looked into the teacher’s eyes and smiled. “He told me everything,” he said.

As Chris walked outside the school building, the sun was warm on his face. The sky was blue, the clouds were white and fluffy, and birds chirped in the trees. Chris smiled. It was a beautiful day.