Rails is a web application framework for the Ruby programming language. Rails is well thought out and practical: it will help you build powerful websites quickly, with code that’s clean and easy to maintain.

The goal of this book is to give you a thorough and complete understanding of how to build dynamic web applications with Rails. This means more than just showing you how to use the specific features and facilities of the framework, and more than just giving you a working knowledge of the Ruby language. Rails is quite a bit more than just another tool: it represents a way of thinking. To completely understand Rails, it’s essential that you know about its underpinnings, its culture and aesthetics, and its philosophy of web development.

If you haven’t heard it already, you’re sure to notice the phrase “the Rails way” cropping up every now and again. It echoes a familiar phrase that has been floating around the Ruby community for a number of years: “the Ruby way.” The Rails way is usually the easiest way—the path of least resistance, if you will. This isn’t to say that you can’t do things your way, nor is it meant to suggest that the framework is constraining. It simply means that if you choose to go off the beaten path, you shouldn’t expect Rails to make it easy for you. If you’ve been around the UNIX circle for any length of time, you may think this idea bears some resemblance to the UNIX mantra: “Do the simplest thing that could possibly work.” You’re right. This chapter’s aim is to introduce you to the Rails way.

The Rise and Rise of the Web Application

Web applications are extremely important in today’s world. Almost everything we do today involves web applications. We increasingly rely on the Web for communication, news, shopping, finance, and entertainment; we use our phones to access the Web more than we actually make phone calls! As connections get faster and as broadband adoption grows, web-based software and similarly networked client or server applications are poised to displace software distributed by more traditional (read, outdated) means.

For consumers, web-based software affords greater convenience, allowing us to do more from more places. Web-based software works on every platform that supports a web browser (which is to say all of them), and there’s nothing to install or download. And if Google’s stock value is any indication, web applications are really taking off. All over the world, people are waking up to the new Web and the beauty of being web based. From email and calendars, photos, and videos to bookmarking, banking, and bidding, we’re living increasingly inside the browser.

Due to the ease of distribution, the pace of change in the web-based software market is fast. Unlike traditional software, which must be installed on each individual computer, changes in web applications can be delivered quickly, and features can be added incrementally. There’s no need to spend months or years perfecting the final version or getting in all the features before the launch date. Instead of spending months on research and development, you can go into production early and refine in the wild, even without all the features in place.

Can you imagine having a million CDs pressed and shipped, only to find a bug in your software as the FedEx truck is disappearing into the sunset? That would be an expensive mistake! Software distributed this way takes notoriously long to get out the door because before a company ships a product, it needs to be sure the software is bug free. Of course, there’s no such thing as bug-free software, and web applications aren’t immune to these unintended features. But with a web application, bug fixes are easy to deploy.

When a fix is pushed to the server hosting the web application, all users get the benefit of the update at the same time, usually without any interruption in service. That’s a level of quality assurance you can’t offer with store-bought software. There are no service packs to tirelessly distribute and no critical updates to install. A fix is often only a browser refresh away. And as a side benefit, instead of spending large amounts of money and resources on packaging and distribution, software developers are free to spend more time on quality and innovation.

Easier to distribute

Easier to deploy

Easier to maintain

Platform independent

Accessible from anywhere

The Web Isn’t Perfect

As great a platform as the Web is, it’s also fraught with constraints. One of the biggest problems is the browser itself. When it comes to browsers, there are several contenders, each of which has a slightly different take on how to display the contents of a web page. Although there has been movement toward unification and the state of standards compliance among browsers is steadily improving, there is still much to be desired. Even today, it’s nearly impossible to achieve 100% cross-browser compatibility. Something that works in Internet Explorer doesn’t necessarily work in Firefox, and vice versa. This lack of uniformity makes it difficult for developers to create truly cross-platform applications, as well as harder for users to work in their browser of choice.

Browser issues aside, perhaps the biggest constraint facing web development is its inherent complexity. A typical web application has dozens of moving parts: protocols and ports, the HTML and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) , the database and the server, the designer and the developer, and a multitude of other players, all conspiring toward complexity.

Despite these problems, the new focus on the Web as a platform means the field of web development is evolving rapidly and quickly overcoming obstacles. As it continues to mature, the tools and processes that have long been commonplace in traditional, client-side software development are beginning to make their way into the world of web development.

Why Use a Framework?

Among the tools making their way into the world of web development is the framework. A framework is a collection of libraries and tools intended to facilitate development. Designed with productivity in mind, a good framework provides a basic but complete infrastructure on top of which to build an application.

Having a good framework is a lot like having a chunk of your application already written for you. Instead of having to start from scratch, you begin with the foundation in place. If a community of developers uses the same framework, you have a community of support when you need it. You also have greater assurance that the foundation you’re building on is less prone to pesky bugs and vulnerabilities, which can slow the development process.

Full stack: Everything you need for building complete applications should be included in the box. Having to install various libraries or configure multiple components is a drag. The different layers should fit together seamlessly.

Open source: A framework should be open source, preferably licensed under a liberal, free-as-in-free license like the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) or that of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Cross-platform: A good framework is platform independent. The platform on which you decide to work is a personal choice. Your framework should remain as neutral as possible.

A place for everything: Structure and convention drive a good framework. In other words, unless a framework offers a good structure and a practical set of conventions, it’s not a very good framework. Everything should have a proper place within the system; this eliminates guesswork and increases productivity.

A database abstraction layer: You shouldn’t have to deal with the low-level details of database access, nor should you be constrained to a particular database engine. A good framework takes care of most of the database grunt work for you, and it works with almost any database.

A culture and aesthetic to help inform programming decisions: Rather than seeing the structure imposed by a framework as constraining, see it as liberating. A good framework encodes its opinions, gently guiding you. Often, difficult decisions are made for you by virtue of convention. The culture of the framework helps you make fewer menial decisions and helps you focus on what matters most.

Why Choose Rails?

Rails is a best-of-breed framework for building web applications. It’s complete, open source, and cross-platform. It provides a powerful database abstraction layer called Active Record, which works with all popular database systems. It ships with a sensible set of defaults and provides a well-proven, multilayer system for organizing program files and concerns.

Above all, Rails is opinionated software. It has a philosophy of the art of web development that it takes very seriously. Fortunately, this philosophy is centered on beauty and productivity. You’ll find that as you learn Rails, it actually makes writing web applications pleasurable.

Originally created by David Heinemeier Hansson, Rails was extracted from Basecamp, a successful web-based project management tool. The first version, released in July 2004, of what is now the Rails framework, was extracted from a real-world, working application: Basecamp, by 37signals. The Rails creators took away all the Basecamp-specific parts, and what remained was Rails.

Because it was extracted from a real application and not built as an ivory tower exercise, Rails is practical and free of needless features. Its goal as a framework is to solve 80% of the problems that occur in web development, assuming that the remaining 20% are problems that are unique to the application’s domain. It may be surprising that as much as 80% of the code in an application is infrastructure, but it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds. Consider all the work involved in application construction, from directory structure and naming conventions to the database abstraction layer and the maintenance of state.

Rails has specific ideas about directory structure, file naming, data structures, method arguments, and, well, nearly everything. When you write a Rails application, you’re expected to follow the conventions that have been laid out for you. Instead of focusing on the details of knitting the application together, you get to focus on the 20% that really matters.

Since 2004, Rails has come a long way. The Rails team continues to update the framework to support the latest technologies and methodologies available. You’ll find that as you use Rails, it’s obvious that the core team has kept the project at the forefront of web technology. The Rails 6 release proves its maturity; gone are the days of radical, sweeping changes. Instead, the newest version of Rails makes a few incremental improvements to maintain relevancy and facilitate common needs.

Rails Is Ruby

There are a lot of programming languages out there. You’ve probably heard of many of them. C, C#, Lisp, Java, Smalltalk, PHP, and Python are popular choices. And then there are others you’ve probably never heard of: Haskell, IO, and maybe even Ruby. Like the others, Ruby is a programming language. You use it to write computer programs, including, but certainly not limited to, web applications.

Before Rails came along, not many people were writing web applications with Ruby. Other languages like PHP and Active Server Pages (ASP) were the dominant players in the field, and a large part of the Web is powered by them. The fact that Rails uses Ruby is significant because Ruby is considerably more expressive and flexible than either PHP or ASP. This makes developing web applications not only easy but also a lot of fun. Ruby has all the power of other languages, but it was built with the main goal of developer happiness.

Ruby is a key part of the success of Rails. Rails uses Ruby to create what’s called a domain-specific language (DSL). Here, the domain is that of web development; when you’re working in Rails, it’s almost as if you’re writing in a language that was specifically designed to construct web applications—a language with its own set of rules and grammar. Rails does this so well that it’s sometimes easy to forget that you’re writing Ruby code. This is a testimony to Ruby’s power, and Rails takes full advantage of Ruby’s expressiveness to create a truly beautiful environment.

For many developers, Rails is their introduction to Ruby—a language with a following before Rails that was admittedly small at best, at least in the West. Although Ruby had been steadily coming to the attention of programmers outside Japan, the Rails framework brought Ruby to the mainstream.

Invented by Yukihiro Matsumoto in 1994, it’s a wonder Ruby remained shrouded in obscurity as long as it did. As far as programming languages go, Ruby is among the most beautiful. Interpreted and object oriented, elegant, and expressive, Ruby is truly a joy to work with. A large part of Rails’ grace is due to Ruby and to the culture and aesthetics that permeate the Ruby community. As you begin to work with the framework, you’ll quickly learn that Ruby, like Rails, is rich with idioms and conventions, all of which make for an enjoyable, productive programming environment.

An interpreted, object-oriented scripting language

Elegant, concise syntax

Powerful metaprogramming features

Well suited as a host language for creating DSLs

This book includes a complete Ruby primer. If you want to get a feel for what Ruby looks like now, skip to Chapter 3 and take a look. Don’t worry if Ruby seems a little unconventional at first. You’ll find it quite readable, even if you’re not a programmer. It’s safe to follow along in this book learning it as you go and referencing Chapter 3 when you need clarification. If you’re looking for a more in-depth guide, Peter Cooper has written a fabulous book titled Beginning Ruby: From Novice to Professional, Third Edition (Apress, 2016). You’ll also find the Ruby community more than helpful in your pursuit of the language. Be sure to visit http://ruby-lang.org for a wealth of Ruby-related resources.

Rails Encourages Agility

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

So reads the Agile Manifesto,1 which was the result of a discussion among 17 prominent figures (including Dave Thomas, Andy Hunt, and Martin Fowler) in the field of what was then called “lightweight methodologies” for software development. Today, the Agile Manifesto is widely regarded as the canonical definition of agile development.

Rails was designed with agility in mind, and it takes each of the agile principles to heart almost obsessively. With Rails, you can respond to the needs of customers quickly and easily, and Rails works well during collaborative development. Rails accomplishes this by adhering to its own set of principles, all of which help make agile development possible.

Dave Thomas and Andy Hunt’s seminal work on the craft of programming, The Pragmatic Programmer (Addison Wesley, 1999), reads almost like a road map for Rails. Rails follows the don’t repeat yourself (DRY) principle , the concepts of rapid prototyping, and the you ain’t gonna need it (YAGNI) philosophy. Keeping important data in plain text, using convention over configuration, bridging the gap between customer and programmer, and, above all, postponing decisions in anticipation of change are institutionalized in Rails. These are some of the reasons that Rails is such an apt tool for agile development, and it’s no wonder that one of the earliest supporters of Rails was Dave Thomas himself.

The sections that follow take you on a tour through some of Rails mantras and, in doing so, demonstrate how well suited Rails is for agile development. Although we want to avoid getting too philosophical, some of these points are essential to grasp what makes Rails so important.

Less Software

One of the central tenets of Rails’ philosophy is the notion of less software . What does less software mean? It means using convention over configuration, writing less code, and doing away with things that needlessly add to the complexity of a system. In short, less software means less code, less complexity, and fewer bugs.

Convention over Configuration

Convention over configuration means that you need to define only configuration that is unconventional.

Programming is all about making decisions. If you were to write a system from scratch, without the aid of Rails, you’d have to make a lot of decisions: how to organize your files, what naming conventions to adopt, and how to handle database access are only a few. If you decided to use a database abstraction layer, you would need to sit down and write it or find an open source implementation that suited your needs. You’d need to do all this before you even got down to the business of modeling your domain.

Rails lets you start right away by encompassing a set of intelligent decisions about how your program should work and alleviating the amount of low-level decision making you need to do up front. As a result, you can focus on the problems you’re trying to solve and get the job done more quickly.

Rails ships with almost no configuration files. If you’re used to other frameworks, this fact may surprise you. If you’ve never used a framework before, you should be surprised. In some cases, configuring a framework is nearly half the work.

Instead of configuration, Rails relies on common structures and naming conventions, all of which employ the often-cited principle of least surprise (POLS) . Things behave in a predictable, easy-to-decipher way. There are intelligent defaults for nearly every aspect of the framework, relieving you from having to explicitly tell the framework how to behave. This isn’t to say that you can’t tell Rails how to behave: most behaviors can be customized to your liking and to suit your particular needs. But you’ll get the most mileage and productivity out of the defaults, and Rails is all too willing to encourage you to accept the defaults and move on to solving more interesting problems.

Although you can manipulate most things in the Rails setup and environment, the more you accept the defaults, the faster you can develop applications and predict how they will work. The speed with which you can develop without having to do any explicit configuration is one of the key reasons why Rails works so well. If you put your files in the right place and name them according to the right conventions, things just work. If you’re willing to agree to the defaults, you generally have less code to write.

The reason Rails does this comes back to the idea of less software. Less software means making fewer low-level decisions, which makes your life as a web developer a lot easier. And easier is a good thing.

Don’t Repeat Yourself

Rails is big on the DRY principle, which states that information in a system should be expressed in only one place.

For example, consider database configuration parameters. When you connect to a database, you generally need credentials, such as a username, a password, and the name of the database you want to work with. It may seem acceptable to include this connection information with each database query, and that approach holds up fine if you’re making only one or two connections. But as soon as you need to make more than a few connections, you end up with a lot of instances of that username and password littered throughout your code. Then, if your username and password for the database change, you have to do a lot of finding and replacing. It’s a much better idea to keep the connection information in a single file, referencing it as necessary. That way, if the credentials change, you need to modify only a single file. That’s what the DRY principle is all about.

The more duplication exists in a system, the more room bugs have to hide. The more places the same information resides, the more there is to be modified when a change is required, and the harder it becomes to track these changes.

Rails is organized so it remains as DRY as possible. You generally specify information in a single place and move on to better things.

Rails Is an Opinionated Software

Frameworks encode opinions. It should come as no surprise then that Rails has strong opinions about how your application should be constructed. When you’re working on a Rails application, those opinions are imposed on you, whether you’re aware of it or not. One of the ways that Rails makes its voice heard is by gently (sometimes forcefully) nudging you in the right direction. We mentioned this form of encouragement when we talked about convention over configuration. You’re invited to do the right thing by virtue of the fact that doing the wrong thing is often more difficult.

Ruby is known for making certain programmatic constructs look more natural by way of what’s called syntactic sugar. Syntactic sugar means the syntax for something is altered to make it appear more natural, even though it behaves the same way. Things that are syntactically correct but otherwise look awkward when typed are often treated to syntactic sugar.

Rails has popularized the term syntactic vinegar. Syntactic vinegar is the exact opposite of syntactic sugar: awkward programmatic constructs are discouraged by making their syntax look sour. When you write a snippet of code that looks bad, chances are it is bad. Rails is good at making the right thing obvious by virtue of its beauty and the wrong thing equally obvious by virtue of ugliness.

You can see Rails’ opinion in the things it does automatically, the ways it encourages you to do the right thing, and the conventions it asks you to accept. You’ll find that Rails has an opinion about nearly everything related to web application construction: how you should name your database tables, how you should name your fields, which database and server software to use, how to scale your application, what you need, and what is a vestige of web development’s past. If you subscribe to its worldview, you’ll get along with Rails quite well.

Like a programming language, a framework needs to be something you’re comfortable with—something that reflects your personal style and mode of working. It’s often said in the Rails community that if you’re getting pushback from Rails, it’s probably because you haven’t experienced enough pain from doing web development the old-school way. This isn’t meant to deter developers; rather, it means that in order to truly appreciate Rails, you may need a history lesson in the technologies from whose ashes Rails has risen. Sometimes, until you’ve experienced the hurt, you can’t appreciate the cure.

Rails Is Open Source

The Rails culture is steeped in open source tradition. The Rails source code is, of course, open. And it’s significant that Rails is licensed under the MIT license, arguably one of the most “free” software licenses in existence.

Rails also advocates the use of open source tools and encourages the collaborative spirit of open source. The code that makes up Rails is 100% free and can be downloaded, modified, and redistributed by anyone at any time. Moreover, anyone is free to submit patches for bugs or features, and hundreds of people from all over the world have contributed to the project over the past nine years.

You’ll probably notice that a lot of Rails developers use Macs. The Mac is clearly the preferred platform of many core Rails team developers, and most Rails developers are using UNIX variants (of which macOS is one). Although there is a marked bias toward UNIX variants when it comes to Rails developers, make no mistake; Rails is truly cross-platform. With a growing number of developers using Rails in a Windows environment, Rails has become easy to work with in all environments. It doesn’t matter which operating system you choose: you’ll be able to use Rails on it. Rails doesn’t require any special editor or Integrated Development Environment (IDE) to write code. Any text editor is fine, as long as it can save files in plain text. The Rails package even includes a built-in, stand-alone web server called Puma, so you don’t need to worry about installing and configuring a web server for your platform. When you want to run your Rails application in development mode, simply start up the built-in server and open your web browser. Why should it be more difficult than that?

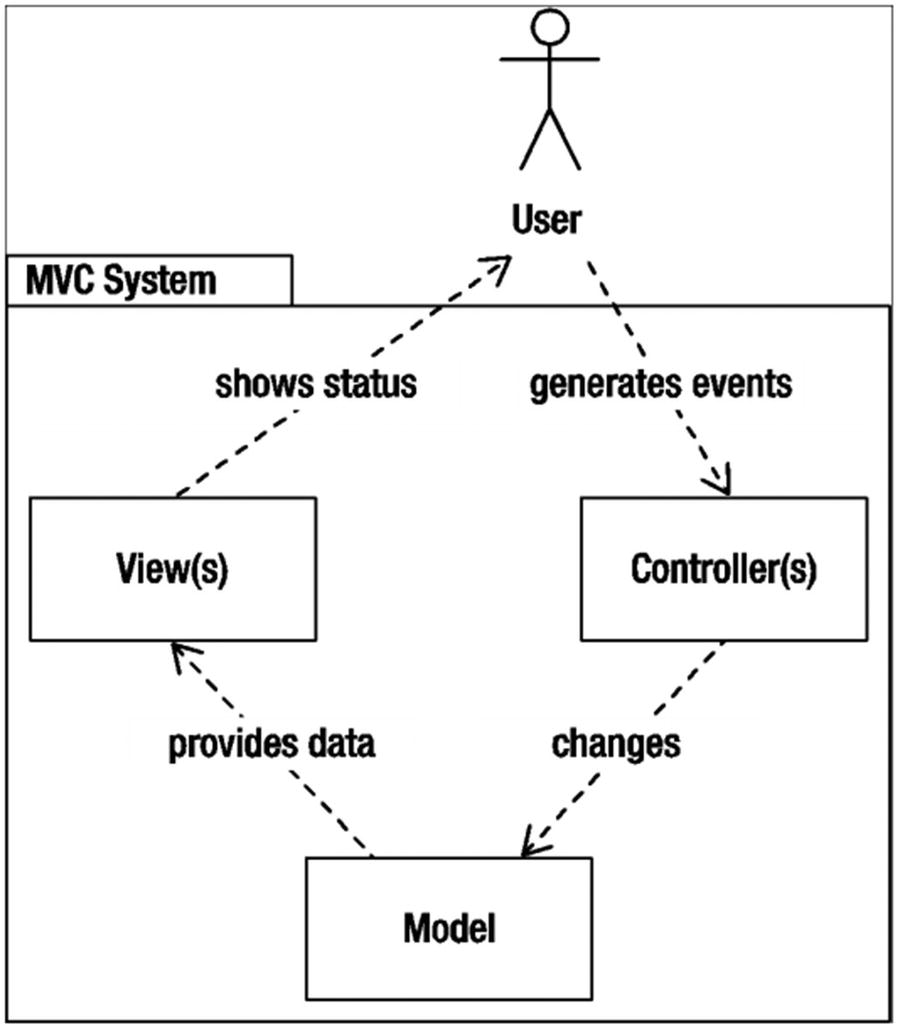

The next chapter takes you step by step through the relatively painless procedure of installing Rails and getting it running on your system. But before you go there, and before you start writing your first application, let’s talk about how the Rails framework is architected. This is important because, as you will see in a minute, it has a lot to do with how you organize your files and where you put them. Rails is a subset of a category of frameworks named for the way in which they divide the concerns of program design: the model-view-controller (MVC) pattern. Not surprisingly, the MVC pattern is the topic of our next section.

Rails Is Mature

You may have heard murmurs that “Rails is dead.” You may have seen graphs that show the popularity of Rails declining. Don’t let that worry you! Though other frameworks may be trendier, don’t assume that means they are better. Rails is still highly effective for building modern web applications and has the benefit of having proved its effectiveness for years. Rails has entered adulthood.

A High-Level Overview of Rails

Rails employs a time-honored and well-established architectural pattern that advocates dividing application logic and labor into three distinct categories: the model, view, and controller. In the MVC pattern, the model represents the data, the view represents the user interface, and the controller directs all the action. The real power lies in the combination of the MVC layers, which Rails handles for you. Place your code in the right place and follow the naming conventions, and everything should fall into place.

Each part of the MVC—the model, view, and controller—is a separate entity, capable of being engineered and tested in isolation. A change to a model need not affect the views; likewise, a change to a view should have no effect on the model. This means changes in an MVC application tend to be localized and low impact, easing the pain of maintenance considerably while increasing the level of reusability among components.

Contrast this to the situation that occurs in a highly coupled application that mixes data access, business logic, and presentation code (PHP, we’re looking at you). Some folks call this spaghetti code because of its striking resemblance to a tangled mess. In such systems, duplication is common, and even small changes can produce large ripple effects. MVC was designed to help solve this problem.

MVC isn’t the only design pattern for web applications, but it’s the one Rails has chosen to implement. And it turns out that it works great for web development. By separating concerns into different layers, changes to one don’t have an impact on the others, resulting in faster development cycles and easier maintenance.

The MVC Cycle

The user interacts with the interface and triggers a request to the server (e.g., submits a registration form).

The server routes the request to a controller, passing any data that was sent by the user’s request.

The controller may access one or more models, perhaps manipulating and saving the data in some way (e.g., by creating a new user with the form data).

The controller invokes a view template that creates a response to the user’s request, which is then sent to back to the user (e.g., a welcome screen).

The interface waits for further interaction from the user, and the cycle repeats.

The MVC cycle

If the MVC concept sounds a little involved, don’t worry. Although entire books have been written on this pattern and people will argue over its purest implementation for all time, it’s easy to grasp, especially the way Rails does MVC.

Next, we’ll take a quick tour through each letter in the MVC and then learn how Rails handles it.

The Layers of MVC

Model: The information the application works with

View: The visual representation of the user interface

Controller: The director of interaction between the model and the view

Models

This snippet, although very basic, searches the users table for the first row with the value Linus in the name column and returns the results. To achieve this, Rails uses its built-in database abstraction layer, Active Record. Active Record is a powerful library; needless to say, this is only a small portion of what you can do with it.

Chapters 5 and 6 will give you an in-depth understanding of Active Record and what you can expect from it. For the time being, the important thing to remember is that models represent data. All rules for data access, associations, validations, calculations, and routines that should be executed before and after save, update, or destroy operations are neatly encapsulated in the model. Your application’s world is populated with Active Record objects: single ones, lists of them, new ones, and old ones. And Active Record lets you use Ruby language constructs to manipulate all of them, meaning you get to stick to one language for your entire application.

Controllers

For the discussion here, let’s rearrange the MVC acronym and put the C before the V. As you’ll see in a minute, in Rails, controllers are responsible for rendering views, so it makes sense to introduce them first.

Controllers are the conductors of an MVC application. In Rails, controllers accept requests from the outside world, perform the necessary processing, and then pass control to the view layer to display the results. It’s the controller’s job to field web requests, like processing server variables and forming data, asking the model for information, and sending information back to the model to be saved in the database. It may be a gross oversimplification, but controllers generally perform a request from the user to create, read, update, or delete a model object. You see these words a lot in the context of Rails, most often abbreviated as CRUD. In response to a request, the controller typically performs a CRUD operation on the model, sets up variables to be used in the view, and then proceeds to render or redirect to another action after processing is complete.

Of course, if you want this controller to do anything, you need to put some instructions inside each action. When a request comes into your controller, it uses a URL parameter to identify the action to execute; and when it’s done, it sends a response to the browser. The response is what you look at next.

Views

The view layer in the MVC forms the visible part of the application. In Rails, views are the templates that (most of the time) contain HTML markup to be rendered in a browser. It’s important to note that views are meant to be free of all but the simplest programming logic. Any direct interaction with the model layer should be delegated to the controller layer, to keep the view clean and decoupled from the application’s business logic.

Generally, views have the responsibility of formatting and presenting model objects for output on the screen, as well as providing the forms and input boxes that accept model data, such as a login box with a username and password or a registration form. Rails also provides the convenience of a comprehensive set of helpers that make connecting models and views easier, such as being able to prepopulate a form with information from the database or the ability to display error messages if a record fails any validation rules, such as required fields.

You’re sure to hear this eventually if you hang out in Rails circles: a lot of folks consider the interface to be the software. We agree with them. Because the interface is all the user sees, it’s the most important part. Whatever the software is doing behind the scenes, the only parts that an end user can relate to are the parts they see and interact with. The MVC pattern helps by keeping programming logic out of the view. With this strategy in place, programmers get to deal with code, and designers get to deal with templates called ERb (Embedded Ruby). These templates take plain HTML and use Ruby to inject the data and view specific logic as needed. Designers will feel right at home if they are familiar with HTML. Having a clean environment in which to design the HTML means better interfaces and better software.

The Libraries That Make Up Rails

Active Record: A library that handles database abstraction and interaction.

Action View: A templating system that generates the HTML documents the visitor gets back as a result of a request to a Rails application.

Action Controller: A library for manipulating both application flow and the data coming from the database on its way to being displayed in a view.

These libraries can be used independently of Rails and of one another. Together, they form the Rails MVC development stack. Because Rails is a full-stack framework, all the components are integrated, so you don’t need to set up bridges among them manually.

Rails Is Modular

One of the great features of Rails is that it was built with modularity in mind from the ground up. Although many developers appreciate the fact that they get a full stack, you may have your own preferences in libraries, either for database access, template manipulation, or JavaScript libraries. As we describe Rails features, we mention alternatives to the default libraries that you may want to pursue as you become more familiar with Rails’ inner workings.

Rails Is No Silver Bullet

There is no question that Rails offers web developers a lot of benefits. After using Rails, it’s hard to imagine going back to web development without it. Fortunately, it looks like Rails will be around for a long time, so there’s no need to worry. But it brings us to an important point.

As much as we’ve touted the benefits of Rails, it’s important for you to realize that there are no silver bullets in software design. No matter how good Rails gets, it will never be all things to all people, and it will never solve all problems. Most important, Rails will never replace the role of the developer. Its purpose is to assist developers in getting their job done. Impressive as it is, Rails is merely a tool, which when used well can yield amazing results. It’s our hope that as you continue to read this book and learn how to use Rails, you’ll be able to leverage its strength to deliver creative and high-quality web-based software.

Summary

This chapter provided an introductory overview of the Rails landscape, from the growing importance of web applications to the history, philosophy, evolution, and architecture of the framework. You learned about the features of Rails that make it ideally suited for agile development, including the concepts of less software, convention over configuration, and DRY. Finally, you learned the basics of the MVC pattern and received a primer on how Rails does MVC.

With all this information under your belt, it’s safe to say you’re ready to get up and running with Rails. The next chapter walks you through the Rails installation so you can try it for yourself and see what all the fuss is about. You’ll be up and running with Rails in no time.