‘When I meet fellow Americans travelling about in North Africa, I ask them, “What did you expect to find here?” Almost without exception, regardless of the way they express it, the answer, reduced to its simplest terms, is a sense of mystery. They expect mystery, and they find it.’

—Paul Bowles, Morocco

The prospect of packing up and setting off for a prolonged stay in a faraway country is one of the most exciting things on offer for us humans. It satisfies the parts of us that crave stimulation, discovery, novelty and change. After all, what could better answer any discontent in our lives than a wholesale change to an environment where we can make a completely fresh start?

But implicit in our yearnings for novelty and change is an element that may go unnoticed, namely that part of us that we gleefully expect to experience all of the wonder, diversion and exotic encounters that a foreign culture offers. We call this part of us ‘I’ or ‘me’. Sadly, perhaps this is the least portable of all the things we might take with us on that journey to another country, and it usually doesn’t survive intact for more than a couple of months.

What happens? Are our personalities so fragile that they can’t be transplanted overseas? Is our sense of self really so dependent on familiar surroundings? If you have spent long periods abroad before, then you probably know already that the answer to these questions is closer to yes than no. Like all organisms, we thrive on stasis and predictability; in fact, our very survival often depends on them. Through a lifetime of experience, we become very adept at maintaining a constant and often predictable relationship with our environment that ensures we will not only survive, but thrive in it. Indeed, we often do everything in our power to ‘keep on an even keel’, and it is universally thought desirable to do so. So it should come as no surprise that a complete change of our mental and physical environment, such as when we get into another culture, comes as quite a shock to our system.

We are shocked even further when we take our lifetime of learning to another culture and put it to work. Two major and, up to now, dependable products of our experience, what we might call our world view and our coping mechanisms, may go belly up right away. They no longer work, because the experience on which they are founded—our aggregate interpretation of people and what they’re about—doesn’t hold up in another country. The people are different, and not only on the outside, in ways we can see such as language, gestures, clothing and looks. Our inability to understand—much less predict—what they may say and do very soon leads us to the conviction that these foreigners are also different on the inside, in ways we can’t see, and this is unnerving. It makes us question not only who they are, but before long it makes us question who we are, because a lot of what we always took for granted about others and ourselves now suddenly looks like it’s up for grabs. The well-oiled machine that we call ‘I’ may appear to be founded on shakier ground than we had ever before imagined.

So does this mean there’s an identity crisis waiting for you on the other side of the airport immigration officer? Ultimately, the answer is probably no, because in the end, the chances are pretty good that you will come to an understanding of the culture you’re in and perhaps a new understanding of yourself that hasn’t completely thrown over the old. The going isn’t always easy though, and the process of getting to a place where you are comfortable, functional and even happy in another culture is what most people understand as the various stages of culture shock.

The process of adapting to a foreign culture is mostly about change, and the change must occur in you. If you are to function happily and productively in a culture foreign to you, then you have to meet that culture on its own terms, because it’s not going to meet you on yours. All the people you deal with—and in the end it is people that you have to adapt to—also have their own lifetime of experiences, but they may have come to very different conclusions than you have about matters both great and small. And here in their own country, it is their rules and their views that prevail, not yours. Your relations with and expectations of others have to be grounded in an understanding of who the others are and what makes them tick, and a great deal of what makes them tick is not what makes you tick.

Culture shock usually occurs in several stages. Let’s look at how these stages might manifest themselves as you prepare to go to Morocco, and what may happen when you get there.

We can’t really say that culture shock begins before you even reach the country, but your expectations about what you will find there may have a great influence on how you respond later. It is probably safe to say about Morocco, as about any other country, that many expectations are founded on the flimsiest of evidence or even on wishful thinking, so that the fewer expectations you have, the better. You may, for instance, have met some Moroccans in your own country and formed an impression of the people on that basis. But remember, you’re not seeing them in their native environment. Moroccans you know may well be going through a culture shock of their own, or they may have made some adaptation to your culture that tells very little about what they are like at home.

In the English-speaking world, the film Casablanca is renowned as a romantic portrait of Morocco during World War Two. In fact, none of it was filmed there, and you would search far and wide to find anything like Rick’s Café in Casablanca today. Similarly, a popular song of the 1970s called ‘Marrakesh Express’ painted a charming picture of the carefree pleasures of hippie tourists in Morocco. But in fact, the trains into and out of Marrakech run at speeds that hardly anyone would think of as ‘express’, and though there are people there ‘charming cobras in the square’, you won’t get within viewing distance of them without being approached by every variety of con artist looking for a way to part you from your hard currency. So you would be well advised to evaluate carefully anything you hear or read about Morocco in advance, and wait for your own experience there to decide what’s real and what’s not.

Unless something dreadful happens upon your arrival in Morocco, chances are that you will thoroughly enjoy the beginning of your stay. It is after all a sunny, friendly, hospitable country where the food is delicious, the scenery fantastic, transportation easy and prices are low. This is what tourists come for, and when you first arrive, you will very likely have that experience too. Many of your pleasurable expectations about the country may in fact be borne out, especially as you get the first taste of the exotic and foreign aspects of Morocco. If this is what you came for, you won’t be disappointed. Morocco is geared up and ready to show you a good time.

But chances are also good that before long, little things—frustrations, irritations, misunderstandings—will start to build up. If you don’t speak Arabic or French, you may find that communication is a serious problem. If you are a woman, you may be mystified and disturbed by all the aggressive attention you receive from men when you’re not aware of doing anything to invite it. If you’ve begun your job, you may be frustrated that what people say will happen and what actually happens seem to have no relation to each other at all. And if you’re just plain human, you may be very uncomfortable with the fact that people seem to stare at you wherever you go. These incidents are all different ways in which Morocco is knocking at the door of your mind. Will you let it in?

Initially, you probably won’t. Even with the best of intentions, the changes that are brought on by planting yourself in the heart of a foreign culture come too thick and fast for anyone to take them on at once. So you may start to selectively block things out, or respond to them in ways that don’t quite feel right. For example:

You start to avoid or strictly limit your contact with Moroccans, because every social or personal encounter ends with you not really understanding what just happened.

You start to avoid or strictly limit your contact with Moroccans, because every social or personal encounter ends with you not really understanding what just happened.

You imagine that people are conspiring to make sure you pay twice as much for everything as a Moroccan would because they think you’re rich.

You imagine that people are conspiring to make sure you pay twice as much for everything as a Moroccan would because they think you’re rich.

You react angrily to a situation before it even happens, because you feel it has already happened too many times before: being cut in front of in a queue, or being addressed obsequiously in French, or being unceremoniously nudged out of the seat you have chosen in a taxi.

You react angrily to a situation before it even happens, because you feel it has already happened too many times before: being cut in front of in a queue, or being addressed obsequiously in French, or being unceremoniously nudged out of the seat you have chosen in a taxi.

You feel unduly depressed about something which wouldn’t have been so significant at home: someone not showing up for an appointment, a few days without a letter from a loved one, being unable to find something in the market you want to buy.

You feel unduly depressed about something which wouldn’t have been so significant at home: someone not showing up for an appointment, a few days without a letter from a loved one, being unable to find something in the market you want to buy.

Along with events such as these, there may be any number of other symptoms that have everything to do with culture shock: physical symptoms of stress such as insomnia, headaches, illness or stomach trouble, irritability, homesickness, feeling helpless and alienated, being obsessive about doing or checking something. Face it! Your system is overloaded, you’re using all the coping mechanisms you know, and for the moment, things seem to be getting worse rather than better.

If you are at this point in your adaptation to Morocco, you are in fact at a fork in the road.

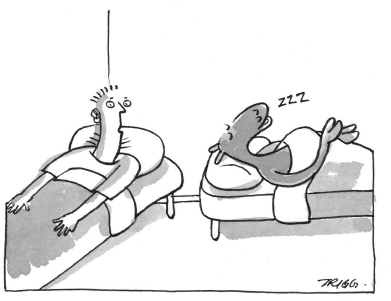

In one direction, you will see the established expatriate community. They have been here a long time, and they have all the answers. They have ‘figured out’ this culture, and even though they seem to have little directly to do with it nowadays, they are quite confident about the conclusions they have reached. You can see them at their lawn party, where the absence of Moroccans is quite conspicuous (except those serving, of course). They know how you feel. They are holding out a cocktail to you and smiling. They are ready to confirm all of your uncomfortable observations and deepen your misunderstanding about the culture, if you will only join them. Sadly, perhaps, most people do. It requires no effort, and enables you to stop where you are now and get back that old but now endangered sense of ‘I’ which was always so comfortable at home. This is the path of least resistance, but it is essentially a dead end as far as your progress in Morocco is concerned. Think twice before you take that cocktail!

Down the other, less travelled fork, the road ahead is a little more difficult to see. In fact, you can’t see much of anything on it, except that there are more Moroccans there than people from your own country. Initially, it is a little lonelier than the first road, but down a little further, it opens up to a broader view that at the moment you can’t even imagine, because you’re not there yet. If you take this road, there is a little more work to be done, but the rewards are worthwhile. You will learn a lot about Morocco and Moroccans; you will probably learn even more about yourself; and you will find a way of living and working in Morocco that brings out the best in it and in you.

You will find this book quite useful whichever road you choose, because how you use the book is up to you. If you want to become an expat armchair expert on Moroccan culture, the facts are here. If you want to make a sincere attempt to cross the bridge to Moroccan culture and be at home in the country, this book will help to get you there.

Please be aware of one thing: this book does not tell you how to adapt successfully to life in Morocco, because that is something that only you will be able to figure out for yourself. This book is not trying to sell you a particular view on Moroccan culture, though it occasionally takes one. This book reflects the experience of many people, but, it is hoped, the presentation of their experience will allow you to draw your own conclusions in time, on the basis of your experience.

The intentions of this book are threefold: to provide a handy reference guide to many aspects of Moroccan culture; to help you avoid some obvious and subtle pitfalls as you set about making a life for yourself here; and to give you the benefit of many other people’s experiences, as points of comparison with your own.

How then do you carry off a successful adaptation to life in Morocco? If there was an easy formula, everyone would be using it. Nonetheless, here are a few hints that, combined with a lot of effort, have not been known to fail:

Study the natives: what makes them react the way they do? If it isn’t clear, it doesn’t hurt to ask questions.

Study the natives: what makes them react the way they do? If it isn’t clear, it doesn’t hurt to ask questions.

Study yourself: what makes you react the way you do? Can you see how your conditioning causes you to respond one way, and a Moroccan another, in the same situation?

Study yourself: what makes you react the way you do? Can you see how your conditioning causes you to respond one way, and a Moroccan another, in the same situation?

Learn the language: if you speak only English, life in Morocco will very often be a struggle. Learning French levels the playing field. Learning Arabic will have innumerable benefits.

Learn the language: if you speak only English, life in Morocco will very often be a struggle. Learning French levels the playing field. Learning Arabic will have innumerable benefits.

Make a friend: Moroccans are very friendly and social people, so chances are you won’t want for companionship. But make the effort to find a friend of your own sex whom you trust, and in whom you can confide. A good Moroccan friend can be your ticket to a much happier life in Morocco.

Make a friend: Moroccans are very friendly and social people, so chances are you won’t want for companionship. But make the effort to find a friend of your own sex whom you trust, and in whom you can confide. A good Moroccan friend can be your ticket to a much happier life in Morocco.

Study your fellow countrymen: people from your own culture in Morocco can be a very useful resource to aid your understanding. Find out how they have coped with various situations that confront you. Investigate whether the point they’ve arrived at is where you want to end up.

Study your fellow countrymen: people from your own culture in Morocco can be a very useful resource to aid your understanding. Find out how they have coped with various situations that confront you. Investigate whether the point they’ve arrived at is where you want to end up.

Take it easy and be patient: Morocco happens to you only a moment at a time, and that is the best way for you to experience it. There is no reason to imagine a dreadful future based on the experiences of a bad day. No one adapts to a culture overnight, and some people might not really find their wings for a couple of years.

Take it easy and be patient: Morocco happens to you only a moment at a time, and that is the best way for you to experience it. There is no reason to imagine a dreadful future based on the experiences of a bad day. No one adapts to a culture overnight, and some people might not really find their wings for a couple of years.

Don’t expect the world: life can be pretty good in Morocco, but it won’t be perfect, and it may in the end be a lot less perfect than where you came from. Morocco is a poor country and in many ways still developing. Not everything is possible here, and there will be days when it seems that nothing is possible at the time you want it.

Don’t expect the world: life can be pretty good in Morocco, but it won’t be perfect, and it may in the end be a lot less perfect than where you came from. Morocco is a poor country and in many ways still developing. Not everything is possible here, and there will be days when it seems that nothing is possible at the time you want it.

Take time for yourself: wherever you are from, it’s unlikely that you will require more companionship than Morocco offers, because it offers it almost continuously. Don’t hesitate to detach from others when you need to, take stock of yourself, and evaluate where you want to go from where you are.

Take time for yourself: wherever you are from, it’s unlikely that you will require more companionship than Morocco offers, because it offers it almost continuously. Don’t hesitate to detach from others when you need to, take stock of yourself, and evaluate where you want to go from where you are.

In a nutshell, living happily in Morocco is a balancing act among three activities: spending time alone, spending time with Moroccans and spending time with your compatriots and other foreigners in Morocco. Each of these is enriching and sustaining in completely different ways, but too much of any one of them can throw you off balance and detract from your ability to enjoy and benefit from the others.

Note on Languages

Arabic and French words appear throughout this book. Guidance for French pronunciation is widely available and so there is no attempt to give any here. A guide for the Moroccan pronunciation of Arabic words and an explanation of the system of transliteration used in this book can be found in Chapter 8: Communication on page 222.