‘We wanted something thoroughly and uncompromisingly foreign—foreign from top to bottom—foreign from centre to circumference—foreign inside and outside and all around— nothing anywhere about it to dilute its foreignness—nothing to remind us of any other people or any other land under the sun. And lo! In Tangiers we have found it.’

—Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad’

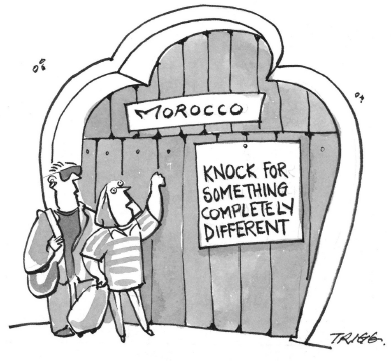

The sharp contrasts visible in so much of the Moroccan demographic landscape—differences between old and young, Arab and Berber, Muslim and European—are in a sense the tip of the iceberg: the evidence of diversity above the surface, where everyone can see it. But there is a lot more happening underneath that is not so obvious. In this chapter, we will begin a deeper excavation to the parts that don’t show at the top, to the inner landscape, in order to find out what makes Moroccans tick.

It doesn’t take very long in Morocco to notice that many of the natives are not only multilingual, but multicultural as well. When they switch from one language to another, the words aren’t the only things that change. The tone of voice, the manner of speaking, the subjects covered, even gestures and personal mannerisms undergo a transformation when a Moroccan switches from Arabic to French, or from Berber to English. Which one is the real Moroccan? All of them are, and more importantly, none of them is fake. Moroccans, even in the remotest village, may grow up with exposure to two distinct cultural patterns—Arab and Berber—and young people are especially enamoured of Western culture. They take every opportunity to internalise it, or at least affect what they see.

The foreign observer may look upon this chameleon-like approach to cultural behaviour as hypocrisy, but the natives generally don’t see it or feel it this way. Moroccans live with contrasts in every sphere of life, and they have a very high tolerance for dualities of all kinds. Consistency of behaviour is not necessarily regarded as a virtue, since behaviour is very much context-driven, and contexts change a lot in Morocco. Moroccans are thus quite masterful at adapting to different contexts, even those which are polar opposites. Hand in hand with this ability comes a talent for reconciling conflicts, for finding a happy medium between the diverse forces and ideas that influence them. In a culture as rich in contrast as Morocco’s, this is not only an admirable trait, it is a survival skill.

There are a few who do not find this balance in the midst of conflicting ideas and methods, and they represent the extremes of Moroccan cultural stereotypes. At one end is the Muslim fundamentalist, who rejects all things Western (especially French), non-Islamic, modern and new. At the other extreme is the completely Europeanised Moroccan, who rejects (at least privately) all things traditional, Islamic, Arabic and old, and embraces their opposites, especially all things French. But these types are small minorities, and most Moroccans do a comfortable juggling act with all of their diverse cultural heritage.

The rest of this chapter will explore the varied influences in Morocco’s rich culture that express themselves in values. We begin with the great unifiers: Islam, family values and the concept of shame. About these, there is little dissent (at least outwardly), little sense of humour and massive conformity.

The influence of Islam is totally pervasive in Moroccan society, so it is helpful for the foreigner to have some understanding of its philosophy, in order to comprehend some potentially confusing phenomena. First, we look at the tenets of Islam, for these are the same throughout the Muslim world and constitute the primer that many people will expect you to be familiar with.

Muslims view Islam as the final and most perfect of the three revealed, monotheistic religions, the other two being Judaism and Christianity. Jews and Christians are recognised by Muslims as People of the Book, and many prophets of the Old and New Testaments are respectfully treated in the Koran, the sacred book of Islam. Thus Muslims are familiar with many biblical figures by their Arabic names, including Moses and Jesus, though they accord them no special distinction among the prophets. For them, the pre-eminent prophet is Mohammed, the founder and revealer of Islam. In conversation and writing, he is referred to as n-nabi, the Prophet, rather than by his name, and no other mortal religious figure compares with him.

Many cosmological and theological ideas familiar to Jews and Christians are also found in Islam, including heaven and hell, the existence of angels and Satan, the importance of faith and a day of judgment. However, Islam rejects the idea of a divine Christ, and of any intermediary between man and Allah. When Muslims refer to Allah, they mean the same God to whom Jews and Christians pray. Allah simply means ‘The God’, distinguishing him from lah, a god, which would be implicitly a false god.

A sincere Muslim observes the five pillars of Islam to the degree possible. Recitation of these is a kind of pop quiz that religious Moroccans put to foreigners, so if you don’t know them, you’ll very likely learn them soon enough:

Making the profession of faith. A person converts to Islam (and you will be admonished, chided and encouraged frequently to do so) by sincerely uttering the profession of faith in Arabic, which translates, ‘There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet.’ This should be done in the presence of two male Muslim witnesses.

Making the profession of faith. A person converts to Islam (and you will be admonished, chided and encouraged frequently to do so) by sincerely uttering the profession of faith in Arabic, which translates, ‘There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet.’ This should be done in the presence of two male Muslim witnesses.

Praying five times a day. The five times are dawn, noon, afternoon, sunset and night. The exact times are determined by the position of the sun and thus change throughout the year. Each time has a particular name, and each is signalled by the mueddin, or prayer announcer, chanting from the minaret of a mosque, usually over loudspeakers. Muslims pray in a mosque if it is convenient, but may pray in practically any clean, relatively secluded spot. Ritual ablutions (washing) are performed before praying. Women generally do not go to mosques, their presence being considered too distracting to the men, but hours are set aside for them to attend at some point in the week. Muslims face Mecca, to the east, when they pray. (Incidentally, you will find that Moroccans tend to orient themselves by locating east, rather than locating north as is more common in the English-speaking world.)

Praying five times a day. The five times are dawn, noon, afternoon, sunset and night. The exact times are determined by the position of the sun and thus change throughout the year. Each time has a particular name, and each is signalled by the mueddin, or prayer announcer, chanting from the minaret of a mosque, usually over loudspeakers. Muslims pray in a mosque if it is convenient, but may pray in practically any clean, relatively secluded spot. Ritual ablutions (washing) are performed before praying. Women generally do not go to mosques, their presence being considered too distracting to the men, but hours are set aside for them to attend at some point in the week. Muslims face Mecca, to the east, when they pray. (Incidentally, you will find that Moroccans tend to orient themselves by locating east, rather than locating north as is more common in the English-speaking world.)

Giving alms to those in need. This is done casually to those begging on the street and in more formal ways, through various charitable institutions. In Morocco, a governmental foundation called the habous oversees religious charity. The Koran stipulates that 2.5 per cent of one’s income and 10 per cent of one’s crops be given in alms, but few seem to observe these strictures. Further information on the treatment of beggars will be discussed at the end of the chapter.

Giving alms to those in need. This is done casually to those begging on the street and in more formal ways, through various charitable institutions. In Morocco, a governmental foundation called the habous oversees religious charity. The Koran stipulates that 2.5 per cent of one’s income and 10 per cent of one’s crops be given in alms, but few seem to observe these strictures. Further information on the treatment of beggars will be discussed at the end of the chapter.

Fasting during the month of Ramadan. Muslims observe a very strict fast, believed to be spiritually cleansing and a sign of one’s faith, between dawn and sunset for a whole month each year. More information about Ramadan can be found in Chapter Six: Food and Beverages on page 181.

Fasting during the month of Ramadan. Muslims observe a very strict fast, believed to be spiritually cleansing and a sign of one’s faith, between dawn and sunset for a whole month each year. More information about Ramadan can be found in Chapter Six: Food and Beverages on page 181.

Making a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in one’s lifetime. Muslims from around the world converge on Saudi Arabia once a year to perform rituals associated with the pilgrimage to the holy sites of their religion. Those who have made the journey gain the title Hajj (for men) or Hajja (for women). The traditional time to go on the pilgrimage is in the 12th month of the Muslim calendar, Du al-hijja.

Making a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in one’s lifetime. Muslims from around the world converge on Saudi Arabia once a year to perform rituals associated with the pilgrimage to the holy sites of their religion. Those who have made the journey gain the title Hajj (for men) or Hajja (for women). The traditional time to go on the pilgrimage is in the 12th month of the Muslim calendar, Du al-hijja.

Any visitor in Morocco will quickly observe that not all Moroccans are doing these things. And yet they call themselves Muslims. What gives? First, remember that Morocco is not considered a ‘hard-line’ Muslim country; life does not come to a halt when prayers begin, eating during Ramadan is fairly common (though never public) and many Moroccans would much rather go to Disneyworld or Paris than make the pilgrimage to Mecca. There is also a prevalent idea, especially among the young, that practising religion is something to do when one is older, married and settled down. But don’t think that on account of this apparent laxity in devotion that Moroccans are not serious about Islam. Their faith in it is such that they feel it embraces them, even without their practising it mindfully. It is the state religion, and you will meet Moroccans only rarely who do not profess a belief in Islam, whatever their outward behaviour may be.

A mosque in Fez in standard Moroccan architectural style.

The following are some features of the inner Moroccan landscape that can be traced directly to Islam.

There is a very strong sense in Islam that all events are preordained, and that one cannot escape one’s destiny. The Arabic word maktoub, literally ‘written’, sums up the idea that everything is already decreed by Allah before it comes to pass. Moroccans say that you cannot escape what is maktoub, written for you.

The practical effects of this point of view are many. To the inexperienced foreigner, it manifests itself primarily as an unwillingness to get involved, a passive acceptance of all that happens without any volition to intervene or change the course of events, even when it appears that one could easily do so.

Fatalism is also evident in Moroccans’ acceptance of their position in life, and a seeming lack of ambition to improve their lot. Those born poor expect to stay poor; those born rich are perfectly at ease with the gulf that separates them from the less fortunate.

When events do not unfold as wished or as planned, Moroccans are generally quite ready to accept the new situation and let go of the past without a lot of remorse, regret or blame. They think it useless to rake over the past since events have transpired in the only way possible.

Finally, the future, from a fatalistic point of view, is highly conditional, contingent on the unknown. The Arabic phrase in sha’ allah, ‘If God wills’, is a standard modifier of anything said of the future. It may often seem to the foreigner that the speaker is giving himself a way out of a commitment, and no doubt this is sometimes the case, but Moroccans feel they would be ‘tempting fate’ to speak of the future with great confidence and without reference to the will of God.

For Muslims, a religion without God, or with many gods, would be blasphemous. Moreover, the lack of religious affiliation or a belief in God is not only incomprehensible, but contemptible to most Muslims. Since Muslims view Islam as the ultimate and perfect religion, the question of conversion to some other faith does not arise. By the same token, practitioners of other religions are encouraged to convert to Islam. Foreigners who do not adhere to one of the monotheistic religions, or who have no interest in exploring Islam, may find that the best course is to avoid religion as a topic of conversation. It can very quickly turn unpleasant if you have strongly held beliefs and views that are contrary to Islam.

Children of Muslim men are considered Muslims from birth. Thus Muslim men may (though as a rule, do not) take non-Muslim wives, but a Muslim woman may only marry a Muslim man. A Moroccan family would certainly consider marrying one of their daughters to a foreigner, but not before he had sincerely converted to Islam. A Moroccan government-issued pamphlet states that, ‘Except for a rather small Jewish community, all Moroccans are born Muslim.’

Not long after the death of Mohammed, questions arose concerning who the true inheritors of his teachings were. This dispute settled into an institutionalised split between the Sunni and Shi’a sects which continues to this day. Moroccans eventually embraced the Sunni teaching, the more orthodox and common form of the religion in the world today, which is practised by a majority of Muslims in all countries except Iran and Iraq.

Although Sunni Muslims everywhere share certain aspects of their beliefs, there are a few features peculiar to Moroccan Islam. Historians attribute them mostly to the meeting of Islam with pre-existing forms of Berber worship, and view them as a compromise between the two. Muslims elsewhere would view these beliefs and practices as unorthodox, but generally not heretical. The two chief features specific to Moroccan Islam are baraka and Murabitin, and the two are inextricably linked.

Baraka means blessing, grace or spiritual power; in some contexts, it may refer to a kind of supernatural power. The word exists in classical Arabic but has a special connotation in Morocco, and is indeed a household word. Baraka is believed to be bestowed upon individuals by Allah. It is also transferable in different ways, most commonly by direct male descent. The prophet Mohammed is viewed as the ultimate human possessor of baraka, and his male descendants are believed to possess it in varying degrees. Baraka is manifested in an individual’s abilities, good fortune and putative spiritual power. It is thought advantageous to associate with anyone who has a lot of baraka, the idea being that some may rub off on you.

Numerous individuals in the course of Moroccan history are viewed as having possessed great baraka. Such men are called Murabitin (singular Murabit), a title somewhat analogous to the Christian ‘saint’. When living, they are revered and looked to as authorities to settle all sorts of disputes. After the death of a Murabit, it is thought that his remains exude some of his spiritual power, and thus they are enshrined in a structure, also called a Murabit (in French marabout, which is also used in Moroccan Arabic). These Murabitin usually consist of a small domed, temple-like structure surrounded by a walled courtyard. Individuals make pilgrimages to these Murabitin in the belief that it is meritorious to do so, and also in the hope that favours or blessings will be conferred upon them. It is especially common for barren women to seek blessings from a Murabit in order to conceive a child.

Murabitin, and those who frequent them, are much more common in the countryside than in urban Morocco. Many Murabitin take on the status of quasi-official charitable institutions, collecting alms and dispensing them to needy pilgrims. Occasionally, however, a Murabit may fall into disrepair and lie in ruins. Murabitin are often maintained by the descendants of the departed ‘saint’, and these in turn live on the alms offered to the Murabit.

In truth, the Moroccan belief in Murabitin and the power of baraka conflict with Islam strictly defined, because they imply a tangible link or intermediary between God and man, which the Koran denies. But these ideas are so widely practised and accepted in Morocco that they have become part of Moroccan orthodoxy.

In the foreground lies the tomb of Moulay Idriss, in the village named for him. Many Murabitin attract pilgrims on their yearly feast day.

Islamic fundamentalism, so prominent in world news from time to time, is less evident in Morocco than in many other Muslim countries, but it does exist. Morocco is among the most liberal countries in the Islamic world, but piety is nonetheless highly respected, so there is no stigma associated with the ardent and zealous practice of Islam—or at least, no stigma that would ever be openly expressed. The Muslim fundamentalist believes in strict adherence to the Koran. This means total, even rigid separation of the sexes, and perhaps complete seclusion of women. Fundamentalists are less inclined to welcome foreigners in Morocco, perceiving them generally as a corrupting influence.

Today there is a small but (to the government) worrying trend towards fundamentalism at Moroccan universities. Students are frustrated by the lack of opportunities available to them and by the growing divide between rich and poor, which they see as a result of Western and anti-Islamic influences. Proponents of these views may favour an Islamic revolution such as occurred in Iran. Greater employment opportunities for the young and educated would go a long way towards weakening this trend.

Fundamentalists are often referred to loosely as the Ikhwan Muslimin, the Muslim Brothers (or Brotherhood), but women are at least as likely to be among them. A fundamentalist man would very likely only take a like-minded wife, but a less ardently religious man would also consider a fundamentalist wife a good match, on the theory that she would be less inclined to be unfaithful.

A few points of etiquette should be observed by foreign men in relation to fundamentalist women, whether the women are married or not. First, they are not likely to shake hands, and it may be embarrassing for them if you were to initiate such a greeting. Certainly if a woman is gloved, whether in her home or on the street, do not offer a handshake. It may also be considered improper even to engage in conversation with such women, unless strictly in a professional capacity. In any case, it is unlikely that foreign men would even come into contact with a married fundamentalist woman in her home, as she would likely be segregated.

A few aspects of belief in Morocco tread the line between religion and superstition, and deserve treatment here. Observance of and belief in all of these is much more common in the countryside, but certainly not unknown in cities, especially among the poor and uneducated. Those who practise or believe in them do not regard them as separate from Islam. Urban or educated Moroccans may denounce them as both backward and un-Islamic.

A few departed saints have followers, usually within a limited geographical area, who observe the saint’s feast day (death anniversary) with bizarre rituals, which may include frenzied dancing, chanting and self-mutilation. These sects are few but well known, and are as much a curiosity to most Moroccans as they are to foreigners.

The English word jinni, or genie, comes directly from the Arabic djinn, denoting a spiritual being that may play some role in human affairs if called upon. Though properly a part of folk religion, belief in djinns is widespread in the Muslim world. In Morocco, they are believed to frequent places associated with water: public baths, drains, sinks, even pots and pans. A plumber working for foreigners in a small Moroccan town was once asked what had become of several taps and fixtures he had installed the previous day (and believed stolen in the night) and, with complete confidence, he attributed the mischief to djinns.

This mythical figure, a beautiful, seductive woman with the legs of a goat, is thought to live under the beds of rivers, in flames and in various other places. She is said to appear to men in dreams, or occasionally while awake. Well known to every Moroccan, children are often frightened of her.

Moroccans are very fond of making music, and very adept at different kinds of rhythmic patterns, often played on various drum- or tambourine-like instruments. There is a belief that many girls and women have an inner, ineffable connection to a particular beat, and when they hear it, they are compelled to dance to it. They may very quickly succumb to the rhythm and appear to go into a trance, in which they are not in control of their actions and seem to be possessed by the spirit of the music. This may culminate in fainting, or even a coma. It is not uncommon at gatherings that include dancing to see a young woman undergo this transformation.

In the countryside especially, sehour, or witchcraft, is practised by women (and rarely by men) to influence another person, usually of the opposite sex. It is almost always used for some dubious purpose, either to arouse love in one that appears disinclined, or to take revenge on one who has been unfaithful or adulterous. It is administered in curses and potions, the latter given surreptitiously in food or drink. At most country markets, one can find a sehhira (witch) who dispenses the peculiar ingredients of her trade and offers advice on their use.

As they direct the administration of curses, witches are also the source of antidotes and remedies for the afflicted. Victims or their families may also seek the aid of a fquih, a religious teacher connected with a mosque, to undo a spell.

Most towns, villages, and medina neighbourhoods have a resident fortune teller (shuwwaf for male, shuwwafa for female) who can, for a fee, reveal the unknown or the future, using cards and other prognostic devices. The reputation of fortune tellers varies with the accuracy of their visions, which can be startlingly on target.

Foreigners may take whatever view of these beliefs they wish, but are best advised to have nothing to do with them. Moroccan women are very often strong believers in the power of witchcraft; men seem to vacillate between scoffing at its alleged powers and fearing that they will be treated with it.

No institution plays a greater role in forging the identity of nearly every Moroccan than the family does. Everything else revolves around family life and is secondary to it, including work, friendship, love and to some degree even marriage. Unless they go away to school or move away to find work, Moroccans usually live with their families until they marry. It is not unusual for a Moroccan man to bring his new wife home to live with his family, especially before they have children. Thus, when Moroccans ask you detailed questions about your family life, it is not out of nosiness but merely their way of placing you in the only context that ultimately matters for them.

If you are alone in Morocco, you will be called upon to explain early and often what in the world you are doing there without any member of your family or a spouse. If you live alone, no one will remark on this without adding meskin, meaning ‘poor thing’.

Moroccans may feel that dire circumstances have driven you to come to their country all alone. The notion that you might enjoy living alone and spending time by yourself will take a lot of getting used to. A Moroccan professor once said that for him, the idea of sleeping alone in a room was like sleeping in a coffin!

Moroccans have separate kinship terms for maternal and paternal aunts and uncles, and other features of their language reflect the primacy of family relations; they use kinship terms—rather than names—for addressing one another. The words for mother, father, brother, sister, paternal uncle, maternal uncle and grandfather (bba, mmu, akh, akht, âm, khal, jed) are all very short, elemental monosyllables and normally carry a personal marker at the end, thus making them ‘my father, my mother’, and so on. Most of the worst insults in Moroccan Arabic either call into question’s one’s parentage, or disparage one’s mother.

For young and old, life centres around the family. Here, a grandmother enjoys the sunshine with her granddaughter.

Volumes of sociological literature notwithstanding, Moroccan families are not all ‘standard’, and thus do not conform to any hard and fast rules about their structure. Nevertheless, there is an indisputable hierarchy in the vast majority of homes. Put simply, age brings veneration, and the young are always beholden to their elders: children to parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents and younger siblings to older siblings. The aged are revered and respected as long as they are able to exert active influence. Thereafter, they are cared for with devotion and dignity.

Whether the mother or the father is the ‘boss’ in the house depends largely on personalities and the configuration of the family. Note, however, that the mother or father who is head of the household may also be a grandparent and mother- or father-in-law to others in the home. A common view is that women orchestrate and supervise domestic affairs, but you will observe that this is not always true.

Among children, a sex-based hierarchy is inculcated early on. The message conveyed is that boys matter and girls don’t. Girls begin to learn the ropes of domestic toil as soon as they are able. Rather than playing with dolls, they may well get to practice real-life surrogate mothering on a younger sibling by the time they are four or five. Boys, on the other hand, are not expected to work around the house and are indulged far more than girls, but they are at the beck and call of their parents and older siblings to run errands.

The institution of marriage is highly esteemed and is viewed as the only normal state for an adult. Americans may say, ‘There’s no escaping death and taxes,’ but the Moroccan proverb is, ‘There’s no escaping death and marriage.’ Marriage and the subsequent raising of children are the natural aspiration of every man and, to some, the only aspiration—indeed, the only justification—for every woman. As another proverb puts it, ‘A woman without a man is like a nest without a bird.’

Marriage is largely an economic and social contract in Morocco, and while not every marriage these days is strictly arranged, parents continue to play an active role in the choice of spouse for their children. Marriage agreements are negotiated much like commercial transactions. The bridegroom pays sedaq, or the bride price, to the family of the bride. In addition to her personal charms and virginity, a bride comes with a dowry, the contents of which are subject to scrutiny by the groom’s family. A marriage to a first cousin is considered a very desirable match because it binds families closer together and also facilitates inheritance within the family. In other words, marriage doesn’t always have much to do with love and romance (which seem mostly to be carried on outside of that institution). The expectations of prospective young brides and grooms are not necessarily of long-lasting conjugal bliss, but of a good working relationship that will enable them to protect and enhance the name of their families by producing children.

Esteem value notwithstanding, not all Moroccan marriages are made in heaven, and an increasing number end in divorce. Young couples are the most likely to divorce, in the early years of a marriage and often before there are children. It is easier for a man to initiate divorce proceedings, but women can also sue for divorce on a reduced number of grounds. Men may also repudiate wives in circumstances where the marriage is deemed to be invalid. Both parties come off badly in cases of repudiation or divorce. All property of the household, and care of the children if any, usually go to the woman; but her chances of finding another husband are quite small, and if she has no education or qualifications, there are very few respectable or desirable ways for her to earn a living.

Under Islam, a man may take up to four wives—but he is obliged to treat all his wives equally, at least with regards to their material needs. In Morocco, this is an effective economic limit on maintaining multiple wives. You will occasionally meet or hear of men who have two wives, but rarely more. Sometimes the wives live together in the same house with all their children, sometimes separate households are maintained where children, if any, live in the house with their natural mother. There is no Arabic equivalent for stepmother and stepfather; the terms used translate as ‘my father’s wife’ and ‘my mother’s husband’ perhaps suggesting the weak link between stepparents and stepchildren.

Pervasive in the Moroccan psyche, and closely related to identification with the family, is the concept of hshuma, or shame. One’s personal honour and dignity, and by extension, the honour and dignity of one’s family, are a Moroccan’s most cherished possessions. Moroccans will go to any lengths to preserve them, and mount great defences if their honour or the honour of their family is ever threatened. Nothing can be worse than for hshuma to descend, raptor-like, and darken one’s name.

It is important here to understand a fundamental difference between Moroccan hshuma and Western guilt. Guilt arises when one’s conscience notes that one has done wrong. Shame arises with the awareness that others know one has done wrong. Guilt plays very little or no part in the conduct of Moroccan life; shame, on the other hand, is paramount. It is the censure of others that a Moroccan shrinks from, since his or her self-image is derived from others and is not cultivated internally.

What kinds of actions might evoke this shame and bring a person or family into disrepute? They fall into the general categories of behaviour that contravenes social norms, that breaks Islamic precepts or that abrogates personal obligations inside or outside the family. The shamed individual faces ostracism from society or even from family, and in the Moroccan context, no punishment could be worse. Misbehaviour by one member of the family impugns the reputation of all, so there is great pressure within the family to protect all its members.

You will probably become aware only gradually of hshuma operating in Moroccans’ behaviour; reading about it and experiencing it are two very different things for someone coming from a Western guilt-oriented perspective. It is perhaps most important at the outset only to be aware of the significance of shame, and thus to adapt your behaviour accordingly. In this regard, the main points to remember are:

If you feel it necessary to reprimand or criticise a Moroccan associate, never do so in public, and try to avoid direct criticism. It is more effective to relate your displeasure through an intermediary (a family member or colleague of the individual) or indicate through your actions that something has gone wrong. The loss of face that a Moroccan would suffer if criticised in front of peers would only threaten the harmony of your future relations.

If you feel it necessary to reprimand or criticise a Moroccan associate, never do so in public, and try to avoid direct criticism. It is more effective to relate your displeasure through an intermediary (a family member or colleague of the individual) or indicate through your actions that something has gone wrong. The loss of face that a Moroccan would suffer if criticised in front of peers would only threaten the harmony of your future relations.

Be aware that what Moroccans say in public and what they confide to you privately may vary a great deal. Much may be said or done in the presence of others merely to make a good appearance, to avoid the loss of face or to prevent embarrassment and awkwardness.

Be aware that what Moroccans say in public and what they confide to you privately may vary a great deal. Much may be said or done in the presence of others merely to make a good appearance, to avoid the loss of face or to prevent embarrassment and awkwardness.

Offering profuse gratitude and thanks to your Moroccan friends for hospitality or favours is greatly appreciated, especially when you do it publicly—even though it may be turned away and diminished with various professions of humility and modesty. A Moroccan adage offers a useful rule of thumb: ‘Praise your friend in public but reprimand him in private.’

Offering profuse gratitude and thanks to your Moroccan friends for hospitality or favours is greatly appreciated, especially when you do it publicly—even though it may be turned away and diminished with various professions of humility and modesty. A Moroccan adage offers a useful rule of thumb: ‘Praise your friend in public but reprimand him in private.’

The French officially ruled Morocco for only 44 years, a short time in a region with such a long history. Nevertheless, partly because the colonial period was so recent, and partly because it was so different from everything previous to it, it still has a very profound effect on Moroccan thinking today.

The average Moroccan has a love-hate relationship with France. The average educated Moroccan has, in addition, a love-hate relationship with his own country. Despite years of intimate association, the French and the Moroccan ways of life are poles apart, and probably always will be. There are some things that are better done in one country, and some better in the other. Moroccans are fixated on these differences and dwell on them with great attachment.

A certain segment of the Moroccan population, typically those somewhat older and not very educated, may have a nostalgic view of the colonial period. Everything worked back then, and it may have been the last time they had a dependable job. Such people may portray the French as honest, upright and enterprising, and rue their departure.

Younger Moroccans are quite often torn between complete immersion in everything French—language, arts, media, consumer goods—and a studied resentment of the influence that these same things exert. They long to travel to France, but at the same time, they disparage it as a godless, corrupt and racist empire. They may behave towards French people with a fawning obsequiousness, seemingly the preferred manner in colonial times. Privately, however, they express hatred at what they see as typical French condescension towards them.

Moroccans who have actually travelled to or lived in France sometimes develop an inferiority complex about their native culture and develop the habit of criticising it, drawing constant comparisons between anything Moroccan and French, in which the Moroccan part always comes up short. Such Moroccans have a well-practised litany of the shortcomings of Morocco and Moroccans, and they may wish you to concur; you may find yourself occasionally in the odd position of defending Morocco to one of its own.

These descriptions are, of course, stereotypes. You may meet many people who fit them, but there are just as many who blend characteristics of several different types, or who adopt any number of different attitudes that seem mutually incompatible. In short, the relationship of the Moroccan to France is a complicated, often muddled one.

What has this got to do with you? Especially if you’re not even French? First of all, if you are European or of European stock, you must come to expect that many Moroccans will respond to you initially as though you were French, with all the baggage that entails. Until there is more evidence to go on, a foreigner is considered French. By those who don’t know you in Morocco, you will be addressed in French more often than any other language, and Moroccans may be surprised if you don’t speak it. Even after many years of evidence to the contrary, there is a prevailing assumption that people of European appearance speak French.

As a foreigner, you must also be prepared, as far as you can be, to deal with the convoluted attitudes that Moroccans hold towards their former colonisers, until you can prove that it is inappropriate for them to pigeonhole you in that way. A good way to do this is to learn to communicate in Arabic. A bad way to do this is to speak only French.

We have seen already that Morocco’s history includes a vast array of governments and rulers, with no structure lasting for very long and with chaos replacing order frequently. One constant, however, is that Morocco has never experienced democracy first-hand. The few have long ruled over the many, and even tribes that were relatively untouched by government rule in early times had a hierarchical authority structure.

What does this mean for you in matters of day-to-day relations with Moroccans? It means that a democratic way of doing things, which you may take for granted depending on where you come from, is completely foreign and incomprehensible to Moroccans in most contexts. The idea of a group decision made by a show of hands, for example, or of a teacher consulting students about what they would like to learn, would be surprising and mystifying. Such things may even be seen as a weakness in anyone who would propose them. In virtually any context, except for friendship among equals, Moroccans expect there to be a leader who makes decisions, and accepts responsibility for them.

The dualities of Islam and the West, old and young, poor and rich—all are inherent in the contrast between tradition and modernity in Morocco. There is much that is old and venerable in Morocco, and only a Moroccan completely alienated from his roots could not have profound respect for the beauty and simplicity of the traditional way of life. But at the same time, it is difficult for any Moroccan not to appreciate the convenience, efficiency and sheer wonder of modern technology, and the Westerners’ apparent freedom in personal behaviour and relationships. So in fact the two exist, old world and new, side by side. This coexistence can be found everywhere: on the modern four-lane superhighway that runs between Rabat and Casablanca, where cars whiz by at frightening speeds, bypassing the pedestrians and donkey carts that make slow progress on the shoulders; at the beach, where one may see veiled mothers side by side with girls in bathing suits; or on a village street where an old man in a dusty jellaba listens to a personal stereo.

Moroccans don’t have a fixed attitude about the massive influx of new technology and behaviour arriving on their shores via foreign investment, aid programs, tourists or even from their own family members returning from abroad. Generally speaking, however, the young are likely to embrace the imports unquestioningly. Older Moroccans are more likely to require proof that something new is something better before they accept it. So the disparity between the traditional and modern roughly parallels a generation gap of staggering proportions. As in nearly every country, the youth of Morocco are often impatient with their old-fashioned parents and want to do everything the modern way.

The major obstacles to greater technical modernisation in Morocco are lack of education and poverty, but many older people would not view these as obstacles, when the old ways seem to work quite well and the new ways threaten stability. Younger people, on the other hand, may seem resentful and impatient of the lowly status and slow progress of their country, compared with European neighbours.

A great obstacle to wider acceptance of Western mores is Islam, though it is perhaps unfair to call it an obstacle, for—even though it entails contradiction—Moroccans old and young are deeply grateful for the values that their religion has bequeathed them, and they may see Western society as depraved and violent.

The gulf between rich and poor in Morocco is very wide indeed, and only shows signs of growing wider. As everywhere else in the world, Moroccans typically reduce the rich and the poor to stereotypes, usually reserving their strongest characterisations for those at the opposite end of the spectrum from where they sit. There is, however, in Morocco a greater acceptance of the divide between rich and poor, owing to the comforting assurances of fatalism: it is all meant to be.

Still, the rich come in for a rather poor showing among those who aren’t. One of the words for money in Moroccan Arabic is wusakh d-dunya, dirt of the world, and the words can be quite menacingly spat from a poor man’s mouth. A rich man with a big pot belly is called kersh al-harem, stomach of sin, on the assumption that his size is due to overindulgence.

The poor go largely ignored and unnoticed by the rich on an immediate, personal level, but the Muslim precept of giving alms provides for a benevolent attitude towards beggars and the poor generally among all Moroccans. Pejorative notions about the poor, such as the idea that they are backward or largely responsible for their plight, are confined to only a tiny minority of wealthy, Europeanised Moroccans.

As a foreigner, you will automatically be perceived as a wealthy person, and by Moroccan standards, you probably are, whatever your status is in your own country. In Moroccan slang, ‘American’ is sometimes used as a synonym for ‘rich’, and in truth, most foreigners who come to Morocco have enjoyed material wealth all their lives that is beyond the means of most Moroccans. It may be helpful to remember this when you feel taken advantage of because of your perceived wealth. Many times, you really are being taken advantage of, and there is probably nothing you can do about it. Chances are that you won’t be fleeced too badly, and you will find it much easier in the long run to simply accept your status as a privileged person whose lifestyle costs a little more to maintain.

The contrasts between city life and country life are also quite sharp in Morocco. The split is a fairly predictable one that occurs in most countries of the world: cities are havens for everything modern, expensive, fast, exciting and changing— perhaps also for everything godless and dangerous. The countryside, on the other hand, is where you find everything old-fashioned and slow, but also cheap, dependable, safe and fresh. These are more or less the prevailing perspectives in Morocco, though admittedly vastly oversimplified.

The ancient divide between rural Berber and urban Arab persists to some degree today. All the parts of Morocco that can still be truly called Berber—where Berber is the language of the street, and most people identify themselves as Berbers—are in the countryside and in mountain villages. Moroccan cities, by contrast, are by and large the strongholds of Arabs. Here, too, stereotypes exist, in which each side is comfortable reducing the other to a caricature. Without getting into the ethnic divide, country people (ârobiyen, which means roughly ‘bumpkin’ or ‘hick’) are viewed as gullible and stupid in the city, whereas country dwellers contemptuously note that those living in the city are fi shiki, conceited or pompous.

Berber farmers cutting fodder in the countryside—a far cry from the bright lights of the city.

One of the most obvious differences between city and country is the relatively greater freedom allowed women in the city. Though one sees fully veiled women in cities, younger women are becoming more and more Europeanised, and even go to cafés now, something that was unheard of a generation ago. In Casablanca and Rabat, native women have even been seen smoking in cafés. Ten years ago, this behaviour would have marked them immediately as prostitutes—and in the countryside, it still would. But Moroccan cities are the vanguard of Europeanisation, home to most of the Moroccans who have lived and worked abroad, and the pace of change is therefore much faster.

The contrast between public and private is not one that Moroccans struggle with; it’s one that they are deeply familiar with, and its inflexible rules are so thoroughly ingrained in them that appropriate behaviour in each context is automatic. It is, however, a contrast that you will struggle with if you haven’t spent time in the Arab world before. Here, it definitely pays to know the ropes before you start pulling on them.

In Morocco, as in other Arab countries, public is very public, and private is very private. They are two separate worlds in which the rules of engagement are completely different and don’t overlap. In rough terms, the contrasts look like this:

Public |

Private |

the street |

the home |

men’s space |

everyone’s space |

everything up for grabs |

everything accounted for |

every man for himself |

defined relationships |

Paradoxically, while Arabs are renowned for their hospitality, the streets of their cities offer some of the rudest and most inconsiderate behaviour found anywhere in the world. These phenomena are really flip sides of the same coin, one side being the public and the other the private world.

In Morocco, the street is the street. It belongs to no one and to everyone. If you’re there, you are inviting any and every kind of attention. It is not considered rude or intrusive to stare at others or approach them on the street, whether you know them or not.

You will notice that eye contact is a kind of game that passers-by play with each other. Being on the street is a spectator sport, where one can be the audience or the attraction. Moroccan Arabic has a word, joqa, that means roughly ‘crowd that forms to watch a spectacle’, and Moroccans do love a spectacle. If you are the only foreigner in a tiny mountain village, the spectacle will be you.

Native women who want to avoid attention on the street cover themselves up, leaving nothing exposed but the hands and the eyes. This is because they know the rules: they are encroaching on men’s space and they want to be as unobtrusive as possible. Women who appear on the street flamboyantly, revealing their hair and lots of skin, are in fact inviting attention, and they get it. Such women all too often are uninitiated foreigners who very quickly become bewildered at the aggressive attention they receive from men. Foreign women who dress modestly (it isn’t necessary for them to cover up completely as traditional native women do) will not receive undue attention.

Life on the street: every man, woman and donkey for him—or herself.

A minority of Moroccan girls and women are in the vanguard of liberating public places for women by going about in ‘provocative’ Western dress, with no gesture towards traditional restraints on their appearance. You will notice that such girls, whether alone or in groups, must brave catcalls and lewd remarks from men and boys they pass on the street. It is a public clash of values that has yet to be resolved.

The essence of street life in Morocco is profane. Without the matrix of family relationships, or those between guest and host that prevail in the home, there is virtually no protocol for the street. People fend for themselves. Moroccans feel no compunction about showing a temper in public, having fierce arguments with tradespeople or even strangers; these are not people one owes anything to, or has to impress. Shopkeepers and other people who work in public do not expect friendliness, nor do they often manifest it. Indeed, excessive friendliness or familiarity in public with strangers may be viewed as weakness or foolishness.

To the foreigner, much of what happens on the street may seem like a complete lack of what we call common courtesy. When a conflict of interest arises, even over very small matters, it probably won’t be resolved by one party politely deferring to the other. More likely it will become a contest of wills, an argument for the sake of winning, whether by superior wit, stratagem or sheer forcefulness. This may all seem quite unnecessary, but remember, there is another side.

Private life, by contrast, is completely different, and often more private and secluded than Westerners are used to. If an Englishman’s home is his castle, a Moroccan’s home is his fortified inner sanctum. The very architecture reveals the sharp separation between street and home: windows are few, and always shuttered if they are at street level. In neighbourhoods that have the space, high walls surround the house to keep out inquiring eyes. The exteriors of houses are often completely nondescript, especially in the medina, suggesting nothing of the spaciousness or sumptuousness that may lie within.

Inside the Moroccan home, everyone has a defined relationship to everyone else. There is no turf to defend, nothing to prove to anyone, and both men and women can let their guard down. Here true gentleness and kindness can be expressed and shared, and everyone is relaxed. It is only at home that Moroccans are really at ease, because the street is no man’s land. From this, it can be seen why Moroccans can really only entertain guests at home. While men may enjoy an outing in a café, it would be unthinkable to offer real hospitality outside the home; there is no public place in Morocco where one could rightly entertain guests.

It should also be noted that, because the home is so private, it is a place that you need to be invited to, until the time comes when you are on very intimate terms with the owner. Except with relatives, Moroccans do not operate a ‘drop-in’ society. If you do have occasion to call at a home where you have not been invited, the treatment you receive will likely be polite but distant. If you aren’t left on the doorstep, you may be shown into a room on the periphery of the house and left there alone till someone can take care of you.

Another distinction roughly parallels the division between public and private. It may not be obvious to foreigners at first glance, but it is of great importance in most Arab countries. Not to put too fine a point on it, the general rule is that the right hand is the public hand, and the left hand the private one.

The right hand is used for shaking hands, for eating out of a common dish, for drinking if one draws water from a cistern, spring or well, for offering or handing over gifts, money or food and when necessary, for touching others.

The left hand is one’s private business. It is used for personal hygiene, to clean oneself after using the toilet. It must never be used with common food (i.e., food that is available to others), and it is better not to use it for handing over objects or money to others.

We save for last the topic that, of all contrasts in Morocco, strikes the foreigner more quickly, more forcefully and more continuously than any other—the differences between men and women, and the behaviours that define and limit them. At the outset, one caveat: trying to generalise about a topic so rife with feeling and under so many competing influences is a little like trying to pin down a wild animal. So you are advised to take in what you read here merely as raw data, to be evaluated on the basis of your particular experience.

The role of women in the home, in society and specifically in their relationship to men is detailed in the Koran in no uncertain terms: ‘Men are in charge of women, because Allah hath made the one of them to excel the other, and because they spend of their property for the support of women. So good women are obedient. ... As for those from whom ye fear rebellion, admonish them and banish them to beds apart, and scourge them.’ It must be noted, before the hackles of indignation arise, that the vast majority of Moroccan men and women are quite convinced of the truth of this formulation, and live contentedly with it. Contact with Western cultures has exposed Moroccans to other gender-based roles, but this contact has not had a great effect in changing behaviour or attitudes.

The separate roles and functions deemed appropriate for men and women penetrate to every area of life. As we have already seen, methods of child-rearing are quite sex-specific. The advantages boys have in the home carry over into education as well. Although school education is in principle free through the first university degree for all Moroccans, far fewer women get the benefit of education, and by the end of secondary school, more than three-quarters of enrolled students are boys.

Underlying the strict division of the sexes in all social contexts is a corresponding view of the fixed roles suitable for men and women in personal and sexual relations. By the time that boys and girls show any interest in the opposite sex, they are scrupulously segregated from each other in any situation in which they would have an opportunity to act on their passions. The only legitimate sexual relations between men and women are held to be those that take place in marriage. The Arabic word bint means girl, and is synonymous with virgin. The word mar’a means woman. A single event on her wedding night separates the girl from the woman, and if this event should happen at any time before her wedding, the girl becomes a woman without a future, burdened with an unshakable mantle of hshuma.

Girls are in a minority by the beginning of secondary school, many having left to learn domestic skills.

If the picture were only this simple, one could expect to find in Morocco paragons of domestic tranquillity and fidelity behind every shuttered window. But alas, other factors cloud the horizon. Marital fidelity aside, it is also assumed that men’s sexual needs are natural, imperious and irresistible. Women, much more grudgingly and judgmentally, are held to have similar needs. So in Morocco, as the world over, much of the melodrama of life revolves around love and betrayal, and popular music is as full of love ballads and laments as the Top 40 anywhere in the world. There is a deeply seated and often expressed mistrust between men and women. Each imagines the other to possess a wildly uncontrollable sexuality that will express itself the moment a chink appears in the institutional armour of sexual segregation; each expects that the other will be unfaithful if given a chance; each characterises the other as the reason for so much difficulty in relationships.

The societal expectation that there be no sex outside marriage is of course irreconcilable with the view that sexual impulses are irresistible—and so various institutions exist to relieve the tension that necessarily accompanies this conflict. Female prostitution, though not officially sanctioned, is widespread in Morocco. It is tolerated but derogated, as in most countries where it exists. Male homosexual prostitution is also commonplace, but happens mostly between foreigners and natives. Finally, homosexual relations among boys and young men are common, before they reach the age where they can be expected to visit female prostitutes.

In the Moroccan mind, sex can only take place between a male and a female, thus lesbianism is unheard of. By the same token, in male homosexual relations, one participant must play the woman’s part, which is thought degrading and unmanly. The Moroccan term for homosexual, zamel, means ‘mount’ and is considered offensive. Thus there is no self-identified ‘gay community’ in Morocco, despite the prevalence of homosexuality.

Female prostitution is widespread in Morocco, from village to city. Supply and demand for it seems to be about equally balanced. Women enter prostitution for a number of reasons, most of them economic. There are very few work opportunities for uneducated or unskilled women in Morocco (domestic service is a major exception) and women who are unmarried, either from divorce, widowhood or spinsterhood, may turn to prostitution to earn a living for lack of any other means of support.

While prostitutes are disparaged, it is not regarded as sinful or shameful for a man to visit a prostitute, unless he is married. Soldiers seem to provide the biggest customer base for prostitutes in Morocco, but single men, before they marry, also use their services. Prostitutes are rather freer in their public behaviour than other women, and indeed their behaviour is very often what identifies them. Women in bars are usually taken to be prostitutes, as well as women who smoke in public—though this is beginning to change in cities. Most towns and cities have a district known for the availability of prostitutes.

In regard to the separate and rather rigidly defined social roles of men and women, foreigners are in a special situation that overall is advantageous. Though foreign women in professional positions do find that they must fight for the recognition that men receive automatically, they are in no way expected to conform to the codes of behaviour for Moroccan women. Foreign men probably enjoy the best of both worlds, enjoying all the advantages that Moroccan society affords men, while at the same time being able to excuse themselves, as foreigners, from occupying male roles that don’t suit them.

Great advantages will fall to those who sojourn in Morocco with a spouse. Having a husband or wife along enables Moroccans to place you in a context in which they can assume your personal needs are taken care of. No one will have any reason to inquire about them.

Those who spend time in Morocco alone, either because they are single or because their spouse is elsewhere, will find early on that it is advantageous to develop stock replies to the oft-repeated questions: Are you married? Why aren’t you married? Why don’t you get married? Why don’t you get married to a Moroccan? And so forth. You should also be prepared for probing and detailed questions about your personal life from Moroccans of your own sex. Even among educated professional men, ‘locker room’ talk is fairly common, and Moroccan women also pull no punches in learning what they can of foreign women’s experiences and outlook.

Moroccans have had adequate exposure to other cultures to develop their own views about foreign sexual and social norms. At the same time, they value very highly the idea that a Moroccan girl is a virgin until her wedding night. In fact, the revelation of her breached virginity is a central feature of the wedding celebration, and the failure to produce it is considered adequate grounds for abandoning the would-be bride. So, in light of the implicit freedom women enjoy in Western films and television, it is not uncommon for Moroccans to view foreign women as ‘loose’, and also not uncommon for Moroccan men to try to take advantage of this alleged ‘looseness’.

It is an erroneous but deeply held conviction of Moroccan men that Western women are a source of continuous and unfailing sensuous delight. So engrained is the stereotype that when a Moroccan male is rebuffed in his (very direct) advances to a Western woman, he is inclined to think that she is just having a bad day, that she is playing hard to get, or that she simply doesn’t conform to type. It is unlikely to occur to him that his behaviour is deeply offensive and insulting.

What Western women view as sexual harassment in Morocco—catcalls, direct propositions, even lewd physical advances—are more likely to be viewed by Moroccan men as a barely conscious or controllable stimulus-response mechanism. Thus for any non-Muslim woman alone in Morocco, her relationship to men, especially in public, becomes a major personal issue.

If only two words of advice could be offered about this subject, they would be Don’t react. Note how modern Moroccan women deal with this sort of behaviour in men: they do not even acknowledge it. Western women are often uncomfortable with the idea that they have to tone themselves down in public, that they can’t be themselves. But you may very well find that the price of ‘being yourself’ in public in Morocco is continuous, unwanted, aggressive attention from men—and that it is much cheaper, more practical and less taxing to ‘be someone else’ in public, just as Moroccan women do.