‘Four things are necessary before a nation can develop a great cuisine. The first is an abundance of fine ingredients—a rich land. The second is a variety of cultural influences. Third, a great civilisation—if a country has not had its day in the sun, its cuisine will probably not be great. Last, the existence of a refined palace life—without the demands of a cultivated court the imaginations of a nation’s cooks will not be challenged. Morocco, fortunately, is blessed with all four.’ —Paula Wolfert, Couscous and Other Foods of Morocco

MOROCCANS ENJOY A FABLED CUISINE, unique and rich in variety. The best traditional cooking tends to be quite labour-intensive, taking for granted the availability of women for work in the kitchen. Fortunately, however, many dishes can also be prepared quite easily.

The variety and complexity of dishes notwithstanding, raw materials for Moroccan cooking tend to be fairly standardised and available in all parts of the country. This doesn’t mean there is no escape from Moroccan cuisine for foreigners who long for a taste of home. All cities have a French-style marché where imported foods, or local imitations of them, are available. But if you live in a village or the countryside, you may have to adapt your diet to some degree; some items such as cheese, good quality rice, wet fish and black tea, for example, are not generally available in rural Morocco.

As for cooking, you can do it yourself or let your maid do it, if you have one; female domestic helpers are nearly always dependable cooks. If you’re a man living alone, your neighbours may think it quite strange for you to do your own cooking. A Moroccan man who lives alone very often has an arrangement with neighbours to do his cooking for him, in exchange for the cost of the food and some nominal fee or other compensation.

Moroccans generally follow a standard three-meals-a-day plan. Following is a look at the general pattern, within which there are infinite variations.

A light meal usually starts the day. Served with coffee or mint tea (more about this in the following pages), the bare minimum for breakfast is bread, with condiments of olive oil or butter, and apricot preserves, all of which are produced in abundance in Morocco. Other kinds of bread that may turn up on the breakfast table are sfenj, deliciously fried, yeast-raised doughnuts; baghrir, very thin, porous, crumpet-like pancakes; milwi, rather oily, thick, heavy pancakes; rziza, a long, spun-out version of milwi, made with spaghetti-like threads of dough shaped into flat cakes; and harsha, an unleavened, semolina-based oily bread. A city café breakfast may include French-style croissant, petit pain, or pain chocolat, all of which are just as good as the ones you buy in Paris, but a whole lot cheaper.

Hot or cold cereals don’t figure much in Moroccan breakfasts, aside from sikuk, a mixture of cous-cous and buttermilk. A more substantial breakfast may include eggs cooked in olive oil and cumin.

As you would expect, breakfast is eaten shortly after getting up in the morning.

Lunch is the main meal of the day, and the heaviest. The minimum ‘lunch hour’ is in fact two hours long, and most businesses shut for three or even four hours in the middle of the day, to allow time for lunch and a nice siesta. Schools let out from noon to two o’clock; businesses shut from around noon until three or four in the afternoon. Nearly everyone goes home for lunch, or goes to someone’s house, so there are in effect four ‘rush hours’ in cities: in the morning, evening, and two in midday.

The most typical lunch dishes, tajin and cous-cous, were discussed in Chapter Four: Socialising on page 96.. The preparation of cous-cous tends to be fairly standard everywhere, with seasonal vegetables and red meat or fowl. Tajins offer more variety but there are a handful of delicious classics that you will probably be served from time to time, and may want to learn to cook yourself. These include:

chicken with preserved lemon and olives

chicken with preserved lemon and olives

lamb with prunes, quince or artichoke hearts

lamb with prunes, quince or artichoke hearts

kefta (spiced ground meat) and egg

kefta (spiced ground meat) and egg

On very special occasions, a Moroccan specialty dish called pastilla (pronounced bas-TI-a) may be served. It is a multi-layered, flaky pastry, usually filled with pigeon, scrambled egg and ground nuts, topped with cinnamon and powdered sugar.

Another dish for grand occasions is meshwi, or roasted meat. Lambs or calves are roasted whole, or in very large pieces, often stuffed with cous-cous or other fillings.

This is a light meal and may be served anytime from 6:00 pm onwards, often not until quite late, even just before bedtime. At the minimum, it consists of harira, a rich stew-like soup whose ingredients vary depending on what’s available, served with bread. For stronger appetites, lunch leftovers may be served, or if guests are present at an evening meal, a lunch-type menu may be substituted.

People who eat a late supper often take a snack break in the afternoon, perhaps around 4:00 or 5:00 pm, that includes coffee or tea, and some breakfast breads, such as milwi or baghrir.

Morocco is hot for long periods of the year, and happily, it offers a wide variety of liquid refreshments to suit nearly every taste. We start with the simplest and work our way up.

Tap water, jokingly called ‘Sidi Robinet’ (robinet is French for tap) is drinkable in most parts of the country, and quite good in mountain towns. However, you will be doing your system a favour by slowly introducing Moroccan microbes to it. Start out your stay with bottled water, which is cheap and widely available. Sidi Harazem is the leading brand, but tastes quite flat and minerally, which Moroccans think is quite healthful. Sidi Ali is also popular, and tastes just like you probably want water to taste, i.e. like nothing at all.

Gerrab, the water sellers, are a common sight in Morocco, especially in crowded public places such as souqs and bus terminals. Typically, they dress in outlandishly colourful garb and wide-brimmed hats. They carry water in hide bags or large earthenware jars and sell by the cup, which may be of brass or pitch-lined clay (the pitch gives a slight flavour to the water which some find desirable). Sometimes, they advertise their water as having come from a particular spring, which you can believe or not, as you wish. Their most common cry is “a-ma baird!” (cold water). When nothing else is available, it hits the spot, provided you don’t mind drinking from a common cup. The price is minimal, a few riyals.

Morocco also bottles its own brand of naturally carbonated water, Oulmes (pronounced WOL-mess), which is widely available and quite delicious.

All major international brands of carbonated drinks are available, as well as some Moroccan ones. These are popular in cafés, and are also often served at home when entertaining. There are, however, no diet drinks available. It is a favourite pastime of Moroccan men to order a soft drink in a café, feel the bottle when it arrives at the table, and reject it for not being cold enough. Note that Coke is called Coka.

Islam forbids the drinking of alcoholic beverages, but they are nonetheless widely available in Morocco. There are numerous bars in French-built parts of cities, but almost all are dives. Villages usually have a shop or two that sell beer and wine, often surreptitiously, since one who openly displays a liking for drink invites hshuma. Hours of opening at such shops are entirely unpredictable and undependable, but shops that sell beer and wine in cities keep regular hours. Hard liquor is all imported, very expensive and confined mostly to foreigners’ commissaries and the haunts of the urban bourgeoisie.

Morocco limits the importation of beer and wine, so if you have a taste for these, you will want to sample the local varieties. There are a handful of bottled beers, all indistinguishable and tasting like a slightly weak American beer. Viniculture is widespread in Morocco, particularly in the Middle Atlas region, and a number of wines are produced for local consumption and export.

Moroccan vintners have yet to capture the praise or even the notice of international oenophiles, but they are trying, and have recently introduced a limited number of vintage labels. Moroccan wine can vary greatly from year to year and even from bottle to bottle, but a few varieties have distinguished themselves as standards. Vieux Papes (red) is the best known standard table wine. Guerouane, in red, rosé and gris, from the region of Meknes, is dependably good. Valpiere is an acceptable white wine. Toulal, one of the new varieties also from the Meknes area, has received favourable reviews from locals. Finally there is Doumi (red)—some of the cheapest, vilest rotgot you are ever likely to taste, and sold, tellingly, in plastic bottles.

Morocco has excellent coffee. Very good quality espresso is served in nearly all cafés, even those in the smallest villages. Cities have coffee shops where several varieties of imported beans are available and ground on the spot. Coffee served at home is also quite good, and is often flavoured with cinnamon, cardamom, black pepper, ginger and other spices.

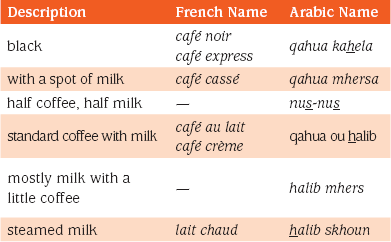

Being such avid coffee drinkers, Moroccans recognise several gradations in the degree to which coffee is diluted with milk. The names of these, which you will find convenient to know when ordering in cafés, are as follows.

Moroccans always sweeten their coffee, and are repulsed by the idea of drinking it without sugar. Hot sweetened milk is also a popular beverage.

Moroccans drink green tea, flavoured with mint and heavily sweetened. This drink, which the locals call simply atai (the general word for tea), is the national beverage. It is the very minimum offered to a guest, whether in a home or a shop (where it may be offered in the interest of getting you to spend more time and/or money there), and Moroccans tend to drink it all day long, at every opportunity they get. It is in fact quite refreshing, and also temporarily calms the appetite. Foreigners often find it too sweet for their taste, but efforts to persuade a host to lay off the sugar are usually unavailing. In cafés, tea is sometimes served with sugar on the side, so you can decide for yourself how sweet to make it.

The green tea that is the basis of this drink is sold in several grades, marked from one to five stars, five being the best and most expensive. Except among the very poor, three star is used at home for everyday use. This five-star rating system tends to spill over into areas of life, and anything described as khamsa njoum (five stars) is the very best.

The common variety mint used in tea is grown all over Morocco. Here too, Moroccans recognise subtle distinctions in quality and flavour associated with different areas of the country that are probably lost on the foreigner. Mint is always sold fresh, and small stands selling fragrant mint, parsley and coriander are a familiar site in every corner of the country.

Two other herb teas are seasonally available in Morocco: shiba (absinthe), which is preferred in cold weather, and louiza (verbena). These are also made by adding the fresh leaves of the plant to sweetened green tea.

Black tea, usually Lipton, is available in city marchés and some cafés. It goes by the name thé noir, or atai kehal.

Cafés and occasionally street vendors sell some other drinks that you may want to try. These include:

halib b-lluz: Milk, almonds and sugar, puréed in a blender.

halib b-lluz: Milk, almonds and sugar, puréed in a blender.

fresh squeezed orange juice: available in many cafés and from street vendors, though the latter have very primitive facilities for washing used glasses. Moroccans often add sugar.

fresh squeezed orange juice: available in many cafés and from street vendors, though the latter have very primitive facilities for washing used glasses. Moroccans often add sugar.

lben: This is genuine buttermilk, curdled by shaking in a container made from a cow’s or sheep’s stomach. It is delicious, but has been known to wreak havoc in foreigners’ intestines, so don’t drink it unless you know the milk it comes from is quite fresh.

lben: This is genuine buttermilk, curdled by shaking in a container made from a cow’s or sheep’s stomach. It is delicious, but has been known to wreak havoc in foreigners’ intestines, so don’t drink it unless you know the milk it comes from is quite fresh.

Morocco offers a well-stocked pantry of delicious food. You’ll find a lot of things there that you’re already familiar with, but also a lot that’s new. The following will help put you in the know about the Moroccan food scene.

Everything is available in its season. In spring, you’ll find apricots, medlars, cherries, strawberries, kiwis and peaches; melons in summer; figs, pomegranates and grapes in late summer and autumn; and in winter, oranges and mandarins. Bananas and nuts (almonds, walnuts, peanuts) are available the year round. There is very little produce imported into Morocco, so what is out of season may be unavailable.

Potatoes, tomatoes and onions are good the year round. In midwinter, there is sometimes a lack of variety in vegetables, with only rooty things available. At other times of year, there is an abundance of everything: squashes, pumpkins, fava and green beans, quinces, eggplants, peppers, artichokes (cheap enough in summer to eat only the hearts) and more.

Olives are cured in several uniquely Moroccan varieties, and are one of the principal passions of foodies in Morocco. Moroccan olive oil is so rich and fragrant you can eat it plain with bread. Argan oil comes from the fruit of the argan tree that grows only in an area west of Marrakech. It has a unique flavour, somewhat reminiscent of olive or walnut oil, and is good in salad dressing.

Standard Moroccan spices are cumin, ground coriander seed, ginger (sold in whole, dried roots), cinnamon, paprika, hot red pepper, turmeric, anise seed, sesame and black pepper. Genuine zafran hurr (saffron) is available, but Moroccans also use a cheap yellow food colourant that they also call saffron. A mixture of spices called ras-al-hanut is what gives many dishes their ‘Moroccan’ taste. It is available in souqs and hanuts. Parsley and coriander leaf (sometimes called cilantro in the United States) are used in almost every dish, and are sold fresh everywhere. Zâter is a herb in the thyme/oregano family, slightly reminiscent of both.

Dairy products don’t figure in large quantities in the Moroccan diet. However, butter and smen, which is butter preserved with herbs and spices, often made from ewe’s milk, are both used commonly. Fruit-flavoured yogurt in serving-sized containers is locally produced under the Danone label. Fresh milk is sold in half-litre paper and plastic cartons. In villages, raw (unpasteurized) milk can usually be bought from a roving milkman, with no guarantee that it is germ-free. Lben is also a specialty of the village and countryside.

As elsewhere in the world, food is a favourite accompaniment to life on the street and is available in ready-to-eat form almost everywhere you go in Morocco. A few paragraphs can’t do justice to the rich variety of street food in Morocco; rather, the following represents those things that should not be missed.

Children are the most frequent consumers of these treats, sold cheaply in paper cones made from recycled notebook pages. Roasted almonds, chickpeas, peanuts, squash and sunflower seeds are the most common. These are also sold in city cafés by itinerant vendors who offer you a free sample, hoping you’ll buy a few dirhams’ worth.

Perhaps the least disparaged vestige of the colonial period is the rich variety of pastry shops and cafés, whose windows showcase exquisite confections that could easily stand up to the competition in Paris. These are much more a feature of cities than villages and are somewhat expensive by Moroccan standards, but the price usually does not deter the sweet-toothed foreigner. There are also a number of native Moroccan sweets, similar to biscuits, that are served in homes for special occasions, or for afternoon snacks.

These are spicy, yellow, fried potato dumplings and are completely addictive. You find them more in the countryside than the city. Ordered by the piece and served with bread.

Grilled meats, cooked over charcoal, are served at sidewalk braziers throughout Morocco. Varieties are steak-like bits of meat, kefta (spiced ground meat) and offal interspersed with pieces of suet. These are usually served unskewered and with a chunk of bread and some hot sauce, along with salt and cumin, the standard Moroccan table condiments. Ordered by the skewer.

There are two kinds of restaurants in Morocco: the familiar kind, where a waiter takes your order from a menu; and a simpler variety, where only a handful of dishes are available, often only at lunchtime, and sitting down is tantamount to saying that you want some of whatever is on offer. The former are found only in cities and large towns; the latter are found everywhere, often near the bus stop or the souq, for they cater mostly to those who aren’t near enough home to eat there.

The larger cities have a variety of restaurants specialising in various international cuisines. They are patronised heavily by foreigners, but also by urban Moroccans, especially the wealthy. They are reasonably priced by Western standards but expensive for the average Moroccan. French cuisine is probably the most readily available, even more common than traditional Moroccan, but you will also find Chinese and Middle Eastern restaurants. International fast food chains are now appearing in Rabat and Casablanca.

The simpler village restaurants, though often quite primitive in decor and amenities, serve delicious, authentic Moroccan food, and are quite economical. They are less often patronised by foreigners, and you may find yourself the object of considerable curiosity if you visit one, but don’t let this deter you from sampling the local fare.

Ramadan is the month in the Islamic calendar during which true believers past the age of puberty fast from dawn to dusk, abstaining also from smoking and sex. Owing to the shorter lunar year which is the basis of the Islamic calendar, the month recedes through the solar year. In 2000, it coincided roughly with the month of December, and starts about 11 days earlier each year thereafter. A complete cycle takes about 33 years.

To the non-Muslim foreigner in Morocco, Ramadan will appear most readily as a complete upheaval in the normal daily routine, especially as regards meals and meal times, hence its treatment in this chapter. Foreigners are not expected to observe the fast, but it is impossible not to make concessions to it, since the whole country is run on a different timetable during Ramadan. Many restaurants do not open at all, markets open late and cafés are shut throughout the day.

Moroccans seen eating or drinking during daylight hours in Ramadan are subject to arrest. Each year, there are a handful of exemplary diners of this kind whose cases are publicised to remind the populace of the consequences. In reality, surreptitious eating and smoking are rampant during Ramadan, especially among young men. As a foreigner, your home may provide the cover for such clandestine munching and puffing, if you are amenable. If the perpetrators are your friends, there is no danger in letting them eat with you; being an accessory to such activity is not a crime.

It is difficult to say whether Ramadan is a greater ordeal in the summer, when Moroccans spend the day parched and dreaming of a glass of water, or in the winter, when empty stomachs make it impossible to ever feel very warm. Whatever time of year it falls, it is an ordeal to be endured. In the daytime, tempers flare at the least provocation, arguments erupt over trivia (even more so than during normal times) and ‘infidel’ foreigners may be particularly singled out for abuse. Indeed, many foreigners make arrangements to be away from Morocco during Ramadan. No seasoned expatriate who employs Moroccans expects to accomplish very much during this time.

In the evening and at night, however, Ramadan is a completely different experience. There is a festive, holiday atmosphere. Moroccans who live abroad often come home during Ramadan just in order to be with family at this time, and hospitality is at its peak. People pour into the streets after the first evening meal (called, appropriately enough, breakfast) and promenade, greeting their friends and enjoying the effects of a satisfied appetite.

All activities restricted during Ramadan are allowed to commence the moment the sun goes down. This is signalled by the firing of a cannon or the sounding of a siren in every hamlet, village, town and city in the country. Television also advertises the times of sunrise and sunset, and gives the signal to chow down.

Breakfast (l-ftour, as in ordinary times) normally consists of harira, a delicious, tomato-based soup served with lemon wedges, dates, milk and a sickly-sweet pastry called shebbakia. Some time later, another meal is served, called l-âsha, the usual name for supper. Finally, the last meal of the Ramadan day is s-sehour, sometimes served quite late at night. Either l-âsha or s-sehour may be the main meal of the day, a lunch-type affair with several dishes and courses, though even more lavish than normal, with many expensive dishes that are traditionally prepared only during Ramadan.

In between these meals, there is general socialising, both at home and in public. Cafés do big business, and the streets are thick with promenaders.

After l-âsha, people may nap for some time. Late in the night, a herald passes through the streets sounding a trumpet, reminding people it is time to eat yet again, before everyone finally goes to bed.

The fast begins again the next day, when there is enough daylight to distinguish a black thread from a white thread in the hand. Few are actually about to make the test, as the rule is to sleep as late as possible, thus shortening the time until breakfast in the evening.

The month of fasting is considered the holiest time of year to Muslims, marking the occasion when the archangel Gabriel transmitted the Koran from Allah to Mohammed. For believers, there are activities in the mosque every night of Ramadan, and on the 27th night of Ramadan, called lilt l-qader, the entire Koran is recited in the mosque. One who dies on this night is said to catch a glimpse of the open doors of Paradise and go right in.

All those who are ill or travelling, as well as women who are pregnant, lactating or menstruating are not required to observe the fast during Ramadan. However, they must make up the days they missed before Ramadan falls again by fasting on days of their choosing.