‘When the soap is used up, the washerwoman rejoices.’ ‘If you want happiness, keep from idle talk and just rest.’ —Moroccan Proverbs

This chapter looks at features of life in Morocco that have mostly to do with your leisure time. For that very reason, it is one of the most important chapters in the book. A successful life in Morocco is one that enables you to release tensions in a way that doesn’t insult or completely deny the Moroccan social environment. Besides that, it is mostly in your spare time that you will develop sustaining and fulfilling relationships with Moroccans, and this activity will make or break your success in Morocco. So if you’re not getting everything from your work that you expected to get, or if it’s not going as well as you want it to, that may not be an indication that you have to work harder; very often it’s an indication that you have to back off a little and gain a new perspective.

A common feature of foreigners’ lives in Morocco is what we might call ‘fishbowlitis’: the tendency to feel that you are unable to escape from a small, enclosed world where you are always being stared at, talked about or even followed. This is no imaginary phenomenon. You may hear of countries where foreigners are left to fend for themselves, but Morocco is not one of them. Moroccans are quite curious by nature, and hospitable and welcoming of foreigners to a degree you may never have experienced before. They are not going to leave you alone, and even if you don’t cultivate close relationships with them, they are still very curious about you. If you live in a town or village where there are few or no foreigners present, the curiosity will be even greater. You may find that you are a spectacle every time you walk down the main street—for it is not considered rude to stare at something or someone curious in Morocco, it is considered normal.

Therefore, as our first task on the road to relaxation, we look at how to get away from it all, and that can often mean no more than taking a day or weekend trip away from where you live to a place where no one knows you and you’re just another foreigner in the crowd. To do that, you need to know how to get there.

Foreigners in Morocco, unless they are working on development projects in rural areas, tend to live in cities, and those who don’t often pay regular visits for rest, recreation and goodies not available in their villages. Among the many options for a getaway, maybe you’ll want to visit a new city in another part of the country, or perhaps even the desert, for a change of pace, or to escape from the ‘fishbowl’ existence foreigners may face. But where do you want to go?

To help with the decision, here are thumbnail sketches of some of the largest Moroccan cities. Morocco has two cities with populations of over a million, and ten other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. About one third of Moroccans live in these dozen cities. In cases where the Arabic name of the city is either different or differently pronounced than the English name, it is given in parentheses.

With three million plus inhabitants, ‘Caza’ (as the locals call it) is by far Morocco’s biggest city. Until the protectorate, it was a fishing village, but the French built a harbour there and developed it—thus it has none of the charms of Morocco’s ancient walled cities. It is a far cry from the 1940s film which made it famous, and those hopeful of finding romantic adventure here would be well advised to avoid it. It is home to some of Morocco’s richest and poorest; its massive sprawl daily attracts migrants from the countryside seeking their fortune. They often end up in one of the many bidonvilles (shanty towns) that dot the city. Morocco’s main international airport is outside Casablanca. Its other quite recent claim to fame is a gigantic Islamic cultural centre and mosque, the largest in the world outside of those in Saudi Arabia that host pilgrims. It was built with contributions from all Moroccans, even those living abroad, who were tracked down and asked to cough up. But today, Moroccans are proud to point to the Mosquée Hassan II as one of the Islamic world’s great monuments.

Rabat is a world away from most of Morocco’s cities. It enjoys a very pleasant, Mediterranean climate, and as the national capital, it is something of a showpiece; its streets are kept incomparably cleaner than those in other Moroccan cities, and no riffraff is allowed to roam the streets, as the king is often in residence. It is probably the most Europeanised city in Morocco; its medina is small and unexceptional, though it is a main centre for the carpet trade. Moroccans in Rabat are almost totally inured to the presence of foreigners, and thus foreigners often feel most at home here; they are little stared at or accosted by guides. There are also dozens of very good restaurants here, catering to all tastes, and reasonably priced hotels are plentiful.

Across the river from Rabat and reachable by car, bus or ferry is Salé (Sla), which shares local government with Rabat but is in every other way a different city. It is older, slower and more traditional; its medina is larger and more exotic than Rabat’s, and mostly ignored by tourists, making it an interesting shopping place for those who know about it. Foreigners are less common here, but not unwelcome. Salé is one of Morocco’s three centres for the manufacture of pottery.

Located in a valley between the Rif and Middle Atlas mountains, Fez is regarded as the intellectual capital of Morocco, and Fassin, natives of Fez, enjoy a sort of mystique, being regarded as the highest rung of Moroccan society. Entering the medina in Fez is as close as one can come to time travel. Its narrow, winding passageways are too narrow for cars, and goods are carried in and out on pack animals as they have been for centuries. The Qairouin mosque and university, in the heart of Fas l-Bali, the oldest and biggest of Fez’s medinas, was founded in the eighth century. It has been an active centre for Islamic studies since then, and is a splendid example of ancient Islamic architecture.

Fez is also home to many of Morocco’s finest traditional craftsmen: carpets, leather goods, woodcarving, pottery and brass goods are all made here, and a walk through the medina will take you by many artisans, young and old, contentedly at their work. Unless your appearance is such that you can pass for a Moroccan, you will not be able to enjoy any of this alone, as the ‘guide’ problem in Fez is nearly epidemic. Many of the guides are students who can be engaged quite reasonably, and are excellent sources of information about the town.

Marrakech shares with Fez the distinction of being one of the most exotic cities in Morocco, indeed, among the most exotic places in the world. It is in the ‘red zone’, with all walls, houses and public surfaces painted a uniform reddish brown. Marrakech was built up by the Almoravids, one of the Berber dynasties of Moorish times, and it is still very much a Berber city. It is also quite definitely on the beaten tourist track, and except for midsummer, when the beastly heat keeps some of them away, it is always packed with Europeans. If you live in Marrakech, you will become known and the ‘guides’ will leave you alone; if you are a casual visitor, you will either have to shake them off regularly, or simply engage one.

The last outpost before the Algerian border, Oujda is the main metropolitan centre of eastern Morocco. It is unexceptional historically and architecturally, except for a small medina. Moneychangers on the street here are ready to change any currency into any other, usually at a rate that compares very favourably with the ones offered in banks. Saidia, north of Oujda on the Mediterranean coast, attracts sun and surf worshippers to its beaches and is an aspiring resort town.

North-east of Rabat, Kenitra is also an unexceptional city whose main claim to fame was a US military base that closed down many years ago. Now it is expanding as part of Morocco’s ‘western seaboard’ of cities, extending from Casablanca northwards, and is served by commuter trains. A fishing and shipping port provides some jobs.

In the north of the country on the Mediterranean coast, Tetouan is in the part of Morocco that was under Spanish influence during the colonial period, and thus has a slightly different flavour from the cities further south. Spanish is on a par with French as a second language here, though Rifi Berber is also very commonly heard. Tetouan is mildly notorious as a distribution centre for hashish. If you value your personal security and happiness, you are advised never to engage in any drug dealings in Morocco, as dire consequences of all kinds can easily follow from even expressing interest.

On the Atlantic coast between Casablanca and Essaouira, Safi is a major port and industrial centre where phosphates, mined on the nearby phosphate plain, are shipped out. Safi also has a petrochemical processing plant. It offers interesting architectural sites from both the Arab and Portuguese epochs of its history, and it is the third of Morocco’s three pottery centres (the others being Fez and Salé). There is a sizable foreign community, mostly French.

Though steeped in as much history as nearby Fez, Meknes has managed to avoid being the kind of tourist trap that parts of Fez have become, perhaps because many travellers are only getting through it to reach Fez. It has a modest medina and several fascinating historical sites, including an underground dungeon built by and for Christian slaves and prisoners, and the ruins of the stables of Moulay Ismaïl, said to have accommodated 12,000 horses. There is also a most pleasant new town where foreigners are pretty well left to their own devices. In summer, Meknes tends to be marginally cooler than Fez (which is an oven), and thus may prove a more attractive destination for those seeking a city break in the Middle Atlas region.

Throwing a pot in Safi , a major pottery centre in Morocco.

Located in the far south on the Atlantic coast, Agadir is the tourist trap par excellence, and is the destination of many package holidaymakers from Europe, especially Germans, who seem to thrive there. It was destroyed by an earthquake in 1960 and built up again. There is nothing very old there, and everything is new, including multistorey beachfront hotels. It is very little like the Morocco one finds anywhere else in the country; indeed, it is in many ways very little like Morocco at all, and thus may serve as an escape for those who need one.

On the Tadla Plain, a large agricultural area in central Morocco, Beni Mellal can probably claim to be Morocco’s most up-and-coming city. It is an agricultural centre, it has a new university and there has recently been some development of light industry. It has no historical claims to fame, but there are scenic areas in the nearby countryside.

Before and during the years of the protectorate, Tangier was an International Zone, administered by more than 20 foreign powers. This has left a legacy in the popular imagination as a place of mystery and intrigue. It is in fact not much more mysterious than any other Moroccan city. Standing at the Strait of Gibraltar, it is the point of entry to Morocco for nearly all tourists travelling by rail, and most European rail passes permit free travel in Morocco.

If you enter Tangier from Europe, be prepared for the guides that swarm around arriving ferries. If you arrive in Tangier by rail from elsewhere in Morocco, the onslaught is less daunting. A short walk from the rail station or the ferry port will bring you to dozens of hotels, so you needn’t worry about finding one, despite what the guides may tell you. The guide plague aside, Tangier is a charming city to walk around in and it has an exotic but manageable medina. The climate is pleasant most of the year round, though winters can be damp and cool.

With the exception of Agadir, Beni Mellal and Tetouan, all of the cities profiled here are reachable by rail. All of them contain universities where Morocco’s burgeoning student population is educated.

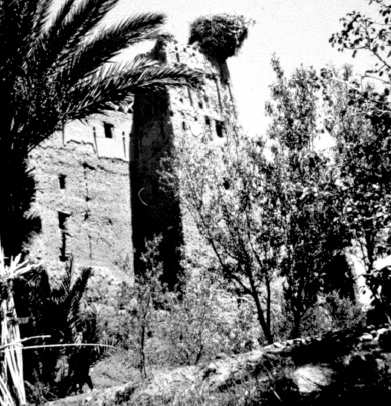

Few people live in the desert and you probably won’t either, but don’t pass up an opportunity to visit there. You’ll find some of the most fantastic scenery and exotic architecture on offer in Morocco. Qsars, which are fortified, walled villages somewhat reminiscent of castles, are a regular feature of river valleys and oases. The best months to visit the desert are February and March. The further south you go in Morocco, the hotter and more arid it gets.

On the subject of getaways, these two cities on the north coast of Morocco deserve mention. They are geographically in Morocco, but politically they belong to Spain. You cross an international border when you enter either city from the Moroccan side. Ceuta, north of Tetouan, is quite small and crowded, really just a shopping strip with nowhere to park. Melilla, near Nador, is larger and more accommodating, with several good hotels, restaurants and parks.

The qsar, or fortified villages, like this one at Aït Benhaddou, is typical of architecture in southern Morocco. A stork’s nest sits on the corner.

Though Moroccans are often hassled by border guards at the crossings, foreigners can enter Ceuta and Melilla easily. They are popular destinations for a number of reasons. They are tax- and duty-free ports offering excellent shopping, especially for electronic equipment and gadgets; both provide ferry service to the Spanish mainland with different boats serving Algeciras, Malaga and Almeira; and they offer a low-cost escape from Morocco, for once you cross the border, you really are in another country. The architecture, food, language and people are all different.

If you are in Morocco only on a tourist visa, you cannot stay longer than three months. A day trip to Ceuta or Melilla constitutes leaving Morocco, and when you re-enter, you have another three months as a legal tourist in Morocco. This is another popular reason for foreigners to visit these cities. However, if you have official residency in Morocco (a carte de séjour), it is not necessary for you to leave every three months.

Border crossings can be either quick and easy or slow and frustrating, depending entirely on the highly changeable moods of the border guards on the Moroccan side. There is also a large seasonal variation in traffic across these borders. August can be particularly slow, as many Moroccans who live in Europe return home for their holidays. Any time you go, you should be prepared for a long wait at the border, often an hour or more; then if you get through quickly, you can be very pleasantly surprised. Before you can even think of getting through, you must fill out an exit visa form. On good days, you will find a stack of these at the border crossing enquiry window. If you don’t see any about, and find no one at the window, make your presence known and try to get things under way. After you have filled out the card, you must surrender it along with your passport to the person at the window. The stamped passport will come back to you after an interval of a few minutes or a couple of hours, again depending on how the guards feel that day. Take a good book to read! Officials on the Spanish side usually ask only to see your documentation, and then wave you on.

If you return to Morocco quite heavily laden with goods you bought in Spain, you may find your load lightened on the way back in by the aforementioned guards. Let this be a caution to you as you feast your eyes on the many wonderful things to buy in Ceuta and Melilla. There doesn’t seem to be any official information on exactly what and how much of anything you can bring in. If you are carrrying what seems to be an ordinary amount of luggage, chances are you will be waved through.

Tourist guides are a kind of plague in Morocco, sometimes infesting even the tiniest hamlet where foreigners appear. The typical guide professes to be a student, usually a university student (one wonders when they ever attended classes), must be in need of your cash to buy books and the like. They are all purported natives of the places they offer to show you around, and usually they are friends of the shopkeepers whose emporia they steer you into. They are all very eager to practise their English and to make a foreign friend. They are all males.

Foreigners’ general experience of tourist guides is unfortunately somewhat negative. Thus you are urged to respond to the guides in a way that will not leave you feeling abused and abandoned. Here are a few tips:

Don’t be bothered by guides in the town or city where you live. They may trouble you at first, but they will very soon get to know who you are and leave you alone. News of foreign residents seems to fly through the guide circuit, and it may surprise you how fast you go from hopeful target to old furniture.

Don’t be bothered by guides in the town or city where you live. They may trouble you at first, but they will very soon get to know who you are and leave you alone. News of foreign residents seems to fly through the guide circuit, and it may surprise you how fast you go from hopeful target to old furniture.

If you want the services of a guide in a city or town where you are not a resident, wait for one whom you feel comfortable with to approach you, and engage him on very specific terms: that is, let him know what you want, and what you’ll pay. If you wish to use English, don’t settle for a guide who doesn’t speak it that well unless you wish to provide English lessons as well as his salary. Don’t pay him until you are finished, and pay him exactly what you agreed upon, along with a tip if you are pleased with his services.

If you want the services of a guide in a city or town where you are not a resident, wait for one whom you feel comfortable with to approach you, and engage him on very specific terms: that is, let him know what you want, and what you’ll pay. If you wish to use English, don’t settle for a guide who doesn’t speak it that well unless you wish to provide English lessons as well as his salary. Don’t pay him until you are finished, and pay him exactly what you agreed upon, along with a tip if you are pleased with his services.

If you do not want the services of a guide who approaches you in a city or town where you don’t reside, dismiss him as politely but as insistently as you can. Bombard him with logical reasons why you don’t require his services, and repeat them as many times as necessary to drive home your point. Do not be rude or aggressive with guides, or your manner will very likely be returned to you with interest.

If you do not want the services of a guide who approaches you in a city or town where you don’t reside, dismiss him as politely but as insistently as you can. Bombard him with logical reasons why you don’t require his services, and repeat them as many times as necessary to drive home your point. Do not be rude or aggressive with guides, or your manner will very likely be returned to you with interest.

Another tactic that may diminish a guide’s interest in you is to make it known that you intend to do no shopping. You will be a much less attractive mark for a guide who stands to make no commissions from your purchases.

Another tactic that may diminish a guide’s interest in you is to make it known that you intend to do no shopping. You will be a much less attractive mark for a guide who stands to make no commissions from your purchases.

There are many advantages to going about with one or more Moroccan friends. You will be approached by guides much less frequently, and your Moroccan friend will probably be able to dismiss those that do approach much more effectively and skillfully than you could dream of doing.

There are many advantages to going about with one or more Moroccan friends. You will be approached by guides much less frequently, and your Moroccan friend will probably be able to dismiss those that do approach much more effectively and skillfully than you could dream of doing.

If you are being relentlessly hassled by a guide and are unable to shake him off, you can approach a policeman with your problem, but be aware that you are probably putting the guide in for some pretty rough treatment at the hands of the authorities. Because of the economic importance of tourism, the government takes a dim view of guides who hassle tourists.

If you are being relentlessly hassled by a guide and are unable to shake him off, you can approach a policeman with your problem, but be aware that you are probably putting the guide in for some pretty rough treatment at the hands of the authorities. Because of the economic importance of tourism, the government takes a dim view of guides who hassle tourists.

So far we’ve concentrated on physically getting away from it all, but most of your leisure time in Morocco will probably be spent closer to home, if not actually in it. Here is a rundown of what foreigners and Moroccans find to do with themselves when they are not working.

One of the great pleasures of visiting or living in Morocco is its cafés. Happily, café life is available to both men and women, for though Moroccan women do not frequent cafés (this is starting to change in cities), foreign women are not out of place there. A foreign woman alone in a café will attract unwanted attention, but in the company of a friend or friends of either sex, chances are she will be left alone.

Nearly every settlement in Morocco from small village to thriving metropolis includes cafés. Modelled very much on the French style, they offer tables both inside and on the street when weather permits. Unlike French cafés, only a small number of those in Morocco serve alcoholic drinks. All of them serve espresso coffee, mint tea, and other drinks (see Chapter Six: Food and Beverages on page 173 for a discussion of these). Moroccan men like to go to cafés alone or with their friends. Most tend to have a favourite where they hang out regularly and are well known.

It is usual for café patrons to spend a great deal of time nursing a single cup of coffee or small pot of tea. The beverage seems not to be the sine qua non of a café visit, rather the ambience is. Moroccans also make what Westerners think are excessive demands on the waiter: calling him over to bring water, being quite picky about the temperature or quality of drinks, snapping their fingers peremptorily when service is needed—but this is all part of the game of social stratification, and waiters, though generally a rather dour-faced lot, don’t protest. It is customary to tip café waiters. Ten percent is thought quite generous, and if you visit a particular café frequently, regular tipping will assure you of good service.

Though many cafés offer some kind of food service, especially in the morning when fresh croissants and petit pain are available, it is acceptable in some cafés to bring food with you to eat along with the beverage you order. Thus you may want to pick up a sfenj (doughnut) or some other food for your breakfast and take it along to the café. It is not advisable, however, to do this at a posh pastry and coffee shop on a smart boulevard in a city.

When weather permits, Moroccans love to go for a stroll in the evening hours, sometime between 5:00 and 9:00 pm or so. (During Ramadan, the promenade slot starts right after breakfast and may go on till late at night). The most popular places for walking are the tree-lined boulevards in a ville nouvelle, but even villages that were bypassed by French development have a main street for people to stroll up and down. Both men and women come out to enjoy the evening air, meet their friends, and perhaps enjoy a drink in a café. The promenade is a very social affair; people dress to look their best, and those that are unattached spend some time checking out others in similar circumstances.

The evening promenade: enjoying a pleasant stroll down Avenue Mohammed V in Rabat.

Most Moroccans do not have bathtubs and showers in their homes. Even those who do make regular visits to the public baths. Moroccans feel, and quite rightly so, that this is the only place to get really clean. A visit to the public bath fulfils several needs—it gets you clean, it is very relaxing, it is a very satisfying ritual, and in the winter, it gets you warm. The public baths are also a very social place, particularly for women: it is one of the few places where they can enjoy each other’s company in the absence of men, though women normally take their young children to the hemmam with them.

A hemmam may be for men only or for women only. More commonly, it is divided in two parts with completely separate entrances for women and men. As another option, men and women will use the same baths at different hours, typically women during the day, and men in the evening. Foreigners are something of a novelty in a hemmam, so you may want to go there first with a Moroccan, or with another foreigner who knows the ropes. If you visit the same hemmam regularly, you will become known there and even expected.

You’ll need to take with you a towel and a change of clothes at least. Most people also take soap and shampoo, but many hemmam sell these in one-shot doses. It is also usual to take some device for scraping the skin, which may be a pumice stone, a loofah or any number of other devices used for this which are sold all over Morocco. A cup or small scoop is useful for dipping water out of buckets. Finally, you may want to take combs and hairbrushes, shaving accessories, a toothbrush or other toiletries. Women go to the hemmam laden with enough accessories to last a weekend by the look of it, but one is assured that everything they take has a purpose.

At some hemmam, tickets are sold at the door, which you then hand over to a person inside. At others, you pay when you finish. The price is quite nominal, about 100 riyals (5 dirhams), usually slightly more for women on the theory that they stay so much longer.

The first room inside the street door of a hemmam is a changing room. There are usually benches to sit on and hooks for hanging up your clothes. Here you undress down to your underwear (DON’T take it off, complete nudity is taboo), leaving your clothes where others have done. Do not put your shoes on a bench, put them under it, or on the shoe rack provided. While your clothes will probably not be disturbed, don’t tempt fate by leaving the pockets stuffed with riches—leave these at home or at your hotel.

If you see stacks of buckets in the changing room, grab a couple. If the hemmam doesn’t seem crowded, treat yourself to three or four, and proceed through the next door.

The business part of hemmam consists of two or three rooms with tiled walls, floor, and ceiling. Each room has a different temperature, the innermost being the hottest, and also the one that has water for you to fill your buckets with. There are normally two cisterns, one of hot and one of cold water. Before you fill your buckets, however, it is customary to stake out your territory: this you do by putting your things down somewhere. This must be done with care, especially if the hemmam is crowded. The main point to observe is, never sit ‘downstream’ from another bather. The floors of the inner rooms slant towards a drain, and you should sit where you are neither in someone’s watershed, nor where your runoff will hit someone already seated. Again, this is a reflection of the pervasive distinction in Moroccan culture between public and private.

By the same token, you must observe propriety in filling your buckets from the cisterns. Water in the cisterns is public; in your buckets, it is private. Thus you should never pour water back into the cisterns from your bucket, as you would be polluting the common source. Similarly, you should not use your left hand to fill buckets from the cistern, or from a common bucket that is used to fill your individual buckets.

Now the buckets. Rinse them out first with a little water from the cistern and pour the water towards the drain. If someone is standing at the cisterns when you get there, they may well fill your buckets for you. This is a common courtesy that you should also extend if you are there when someone else comes. Take your filled buckets back to your bathing site, but before sitting down, rinse your floor space. Though it may not be visibly dirty, this is done as a ritual cleansing of the spot, to remove the residue of the previous bather and make it clean for you.

Now the hard part is over. Sit down and sweat for a while.

Most people do their initial sweat in the hottest room, but if you are unused to sauna or steambath-like temperatures, don’t stay in too long. You will notice that people in the hemmam do various kinds of stretching exercises, and may give each other massages or help each other with stretching. For sedentary housewives or shopkeepers, this is a way of keeping muscles in tone, taking advantage of the warm temperatures that loosen the body up. Someone may offer to ‘work you over’ and there is no reason you shouldn’t let them, and reciprocate if you wish. If it is another bather, this is offered as a courtesy, but be aware that most baths also have a professional, called a kias, who will do the whole massage-scrape-soap routine on you for a fee.

After you have sweated for some time, it is customary to scrape the skin, in order to remove the outermost layer of dead, soiled skin. It comes off in small spaghetti-like threads that can be rinsed off with water from your buckets.

Soap and shampoo come next. In some hemmam, you can apply these in whichever room you wish, but in others, soaping up is never done in the hottest room. See what others are doing. If you have to move, find and rinse off a spot in a different room, by the same procedure described earlier. Be careful not to splash anyone else with your suds or water. People who come to a hemmam together usually help each other wash as well, especially the hard-to-reach places.

When you are finished, you can return to the changing room, taking your buckets with you if you wish, though you needn’t. Some people take a half-bucket of water with them to rinse their feet off just before putting on their socks.

A man with a towel over his head has just come from the hemmam, or public bath, in Sefrou.

After bathing, you will be greeted with b-sehahatik (To your health). The response is allah iyâtik s-sehah (God give you health).

Movie houses in Morocco are male spaces, except for a few posh cinemas in the big cities, usually showing European films, where women may enter unaccompanied by hshuma. Standard fare in Moroccan cinemas are Indian films, curiously not dubbed or subtitled in any language used in Morocco. There is also a large audience for the kind of international ‘junk’ films featuring car chases, big guns, martial arts, voluptuous heroines and the like. Low-budget, inane comedies from Europe, what we might call Eurotrash, are also popular. Audiences at these films tend to be young, boisterous males who talk and smoke during the entire feature.

Cinemas showing better quality European and American films, either originally in, dubbed in or subtitled in French, can be found in cities. Audiences in these are slightly more subdued, but smoking is still usually permitted.

A number of cities also offer cinéclubs, private clubs that use a commercial cinema once a week to show films that the club selects: usually Western films in or rendered in French. These clubs offer the best film viewing in Morocco. Membership is usually open to anyone, and fees are modest. The clubs may also offer you a way of meeting like-minded Moroccans. Women are usually as welcome in cinéclubs as men are.

Rabid enthusiasm for sports, particularly football (soccer) is as common among males in Morocco as in any other country. Most of them follow European and international competitions keenly, especially in the run-up to World Cup competition; familiarity with various teams and even individual players is widespread. Matches are aired on television at least weekly in season. These are then rehashed endlessly in cafés until there is a new match to talk about. Foreign men interested in sports will find ample company in Morocco.

Moroccan boys and men also love to play football, and pickup games can be found everywhere, particularly at the beach. Almost everyone plays barefoot when weather permits.

There are tennis courts and golf courses in or near most Moroccan cities. Few of them are public, but many have some policy for permitting non-members to use them. Your compatriots in Morocco are the best source of information about these places, as they tend to be heavily patronised by foreigners.

What are the women doing while the men are out enjoying the world? To complete the stereotyped picture, the fact is that they are probably working at some domestic activity. As well as being expert in the expected household occupations—cooking, cleaning and child-rearing—Moroccan women are accomplished in a number of other domestic arts and crafts. Sewing, knitting, embroidery and crocheting are all popular. Foreign women who take an interest in these activities will find it easy to share them with Moroccan women.

Accomplished amateur musicians abound in Morocco, and making music is a favourite activity wherever people are gathered, especially at home. Men and women participate equally in singing, although stringed instruments such as the three-stringed lotar, the eleven-stringed l-âoud, or the kamanja (fiddle) are usually played by men. Men and women both play various percussion instruments resembling drums or tambourines, all made from skins stretched over ceramic or wooden frames. The most popular are the derbouka, the târija and the bendir.

Folk dancing in groups very often accompanies music. Dancing in pairs is usually between members of the same sex. Men and women both perform a uniquely Moroccan hip-gyrating motion which is thought to be quite alluring. Moroccans are quite eager to initiate foreigners into their music and dancing, and it is a pleasant way to spend time together where music is the common language and no other is needed.

The Communication Age has definitely come to Morocco, and generally you will not want for printed and electronic information. Here is a summary of what’s available.

In cities you can buy the International Herald Tribune in the evening of the day it’s published. The international editions of Time, Newsweek, and sometimes The Economist are also available. Daily newspapers from the English-speaking world are sporadically available at a couple of newsstands in Casablanca and Rabat; the kiosk in the Rabat train station has the best selection of English-language newspapers and magazines.

A monthly English-language newspaper, The Messenger of Morocco, written by and for the English-speaking community of Morocco, is published in Fez and is easy to find there, but a little more difficult elsewhere. It carries interesting articles on culture, tourism, leisure and sports.

A wider selection of French and Arabic dailies and weeklies can be found everywhere. Several newspapers in each language are published in Morocco, and newspapers from all over the Arab world, and the Paris dailies are widely available. Other European dailies can be found in large cities a day or so after publication.

There are American Bookstores, affiliated with American Language Centers, in Rabat, Casablanca and Marrakech. They offer a good selection of reference books, fiction and nonfiction, mostly in paperback. Other independent bookstores specialising in English-language books can be found in Fez, Oujda and Rabat. The English Book Shop on rue Al-Yamama in Rabat, behind the train station, has a good selection of used paperbacks at very reasonable prices.

Magazines and newspapers in French, Arabic and the main European languages are widely available in Morocco.

Subscriptions from abroad are not reliable. If you must read something other than what is listed here, have someone send it to you, or if possible, receive it through your embassy or consulate.

Morocco now boasts two television stations. One is state run, the other nominally independent. Both carry advertising. Programming is very wide-ranging and eclectic: you can study the beautiful calligraphy of the Koran on the screen while it is being chanted, or sample the latest rock videos from Britain and America. Films and soap operas from the Arab world (mostly from Egypt) figure prominently, and other internationally syndicated series, mostly American, are shown weekly. In addition, there are sports matches, nature programs, Moroccan music, news (always with an upbeat, pro-government slant) and all the other things you expect to find on television. There is a fairly even split between programming in French and Arabic. There is very little in English, except the occasionally subtitled film, and of course the rock and rap videos.

Satellite television, which is taking Morocco by storm, has a wide range of English-language programming. It carries the NBC Superchannel, MTV and several European and Middle Eastern channels that offer news and other programs in English.

A great listening selection is available if you’ve got a good radio. Either take with you or buy a good quality multi-band radio that has AM (also called medium wave, or MW), FM, long wave (LW) and especially short wave (SW). A wide variety of Moroccan stations broadcast many different programs on AM and FM featuring all the different kinds of Moroccan music (there are more than you would ever imagine) and music from elsewhere in the Arab world, as well as Western popular music. There is a little programming in English, but Arabic and French are the standards. On long wave and short wave, you can pick up stations from around the world, many of which broadcast in English, including Voice of America and the incomparable BBC World Service.

Islam frowns upon the use of representational images, especially as art. You will notice that no image of the prophet Mohammed exists anywhere. This fact may go some way towards explaining the aversion that Moroccans have to casual picture-taking by tourists. Moroccans don’t generally own cameras or many photographs themselves, and the photos they do have are usually rather formal, commemorative shots of some special occasion.

If you wish to show some sensitivity to cultural norms, you shouldn’t take someone’s picture without asking them first. Doing so is considered rude and it may evoke an aggressive reaction. If you are on the tourist track, don’t be surprised if your request to take someone’s picture is answered by a request for money from you.

If you are off the beaten tourist track, be even more careful about taking pictures of people. You may arouse the suspicion of the local people, or worse, the authorities. Cameras are rare items in rural Morocco and the idea of taking souvenir photos of what for Moroccans are everyday affairs is very unfamiliar.

You should not photograph any public buildings in Morocco. This means any government buildings and offices, police stations, and offices of the Bank of Morocco. Doing so could result in the seizure of your camera, your film, yourself or the triple-whammy: all of the above. You may, however, photograph your friends and family with such buildings as Parliament or a post office in the background without causing a stir.

Film in widely available in Morocco, though you may not easily find film types used more by professional than casual photographers. Film processing is also available in cities, but is expensive and not always of good quality. Many foreigners choose to buy film with prepaid processing mailers, and send the film for development to laboratories in Europe.

Morocco celebrates the holidays of the Sunni Muslim calendar. During these holidays, schools and government offices close. Some businesses close, others don’t, but any business that employs large numbers of Moroccans closes on the major Islamic holidays.

Morocco also has a few of its own holidays that entail the same closures. Additionally, the government has recently added other holidays to the calendar, most of them extolling its own accomplishments in various arenas. They vary in the extent to which they are observed, but all of them are days off for civil servants at least.

Holidays celebrated by Muslims the world over are based on the Muslim calendar. Keep in mind that the Muslim year is shorter than the solar year, and so each year these holidays come 10 or 11 days earlier than the previous year; thus they gradually work their way through the seasons. All Islamic holidays begin officially at sundown on the evening before the official date of the holiday.

This is Arabic for ‘little festival’, which is celebrated on the first day after the month of Ramadan. Elsewhere in the Muslim world it is called âid al-ftir, or ‘breakfast festival’. It marks the end of the month of fasting.

This is Arabic for ‘big festival’ and it is the biggest holiday in Morocco. Elsewhere in the Muslim world, it is called âid al-adha. It is celebrated on the tenth day of the month of Du al-hijja, the month during which Muslims make a pilgrimage to Mecca. For reference, it occurs roughly two months and one week after the end of Ramadan. But if you’re in Morocco, you’ll know it’s coming, because everyone will be talking about it. Âid al-kebir is to Moroccans what Christmas is in most Western countries: a time that everyone looks forward to spending with their families, to relax and enjoy each other’s company. Normally, it is a two-day holiday, but not a lot gets done on the day before or the day after, because everyone is travelling to and from visits with their families. The holiday commemorates the sacrifice of a sheep by Ibrahim, who was directed to do so by Allah rather than sacrificing his son. This story from the Koran also occurs in the Bible, Ibrahim being none other than Abraham. For this holiday, every Moroccan family tries to buy a ram, which is ritually slaughtered then eaten over the next three days. The holiday is a carnivore’s delight, but vegetarians would be well advised to make themselves scarce for this one, as many people eat virtually nothing but meat for the duration of the holiday.

Every Moroccan family aspires to slaughter a ram at Âid al-kebir, the main holiday of the Muslim calendar.

Called mawlid an-nabi elsewhere in the Muslim world, this two-day celebration marks the birthday of the prophet Mohammed. It falls on the 12th and 13th of Rabia I, three months after âid al-kebir.

This holiday, falling on the tenth day of Moharram, marks the day Ali, prophet Mohammed’s son-in-law, was murdered in the mosque. It is primarily a Shi’a Muslim holiday, and is celebrated in Morocco as a gift-giving occasion for children. It is not a day off from work.

These holidays are observed according to the Western calendar, and thus fall on the same day every year. Except for Labour Day, they are all marked in grand style by the government, since they celebrate milestones in its history. Towns and cities are festooned in bunting and portraits of the king, and there are often public celebrations and ceremonies as well as extensive television and radio coverage.

This is Arabic for coronation festival, and marks the anniversary of the coronation of King Hassan II. It falls on 3 March.

This is Labour Day, celebrated on 1 May, as in most parts of the world. Trade union members have the day off and there are rallies featuring slogan-chanting and the like. Otherwise, life goes on as normal.

This is Green March Day, 6 November. It commemorates the 1975 march of 350,000 Moroccans, led by King Hassan II, into the Sahara to claim it for Morocco after it was relinquished by Spain. The holiday is an occasion for Moroccans to celebrate unity and patriotism.

This is Independence Day, 18 November. It marks the day on which Morocco declared its independence from France in 1956, when the protectorate ended.

Other holidays on the calendar are observed more by the government than anyone else and include New Year’s Day, 1 January; National Day, 23 May; Youth Day, 9 July; Oued d-Dahab Day, 14 August; and something called ‘Revolution of the King and the People’ on 20 August.

A moussem is the birth or death anniversary of a saint, i.e., a murabit. Depending on the saint’s renown, these can be anything from low-key, hardly noticeable local affairs to major festivals. Some of them attract foreign tourists; many more of them attract Moroccan tourists, who may view them as opportunities for a sort of mini-pilgrimage. Among the most popular moussem are Moussem Moulay Abdellah in El-Jadida in August, Moussem Moulay Idriss in Meknes in September, and Moussem Moulay Idriss Al Ashar in Fez in October.

There are occasionally interesting festivities to watch or participate in at a moussem. These include folk dancing by shikhat (women dancers) or genaoua, a class of black dancer-musicians who travel about in small groups and play drums, dance, and excite crowds to frenzied gyrations. Moussems are usually accompanied by a souq as well that serves the needs of those attending. Country people often arrive with their tents to spend several days at the moussem.

Another regular feature of a moussem and other Moroccan celebrations is the fantasia: a group of horsemen in ceremonial dress line up at one end of a large field, and as they approach the other end at a gallop, rise up and fire their rifles into the air in unison. After they finish, the crowd oohs, aahs and applauds, and then the horsemen do it again. Despite the low-tech presentation of the spectacle in comparison to Western diversions, it is very impressive entertainment, taken very seriously by the horsemen and their audience.

Men and horses dress up for a fantasia.

There is no official recognition of Western holidays in Morocco except for New Year’s Day. There is some awareness of Christmas, called âid al-massih (Messiah’s festival) or Nöel, and Easter, usually known by its French name Paque. The school year is set up such that Christmas nearly always falls during the winter school holiday; Easter may or may not fall during the spring school holiday, which is usually around the last week in March.

Though many Moroccan holidays are set by the Muslim calendar, the Gregorian calendar is by far in greatest use, with the French names of the months predominating over the Arabic ones. Moroccans write dates European-style when writing in French, i.e. day/month/year, and just the reverse of that when writing in Arabic, i.e. year/month/day.

Throughout Morocco, there are seasonal festivals that celebrate local events. The Moroccan National Tourist Office has begun capitalising on these, which in some cases has meant that they have lost their local flavour, but has also insured that there are better facilities for those visiting. It should be borne in mind, however, that where there is a conflict between the religious and the secular calendar, the religious one will usually prevail. This is worth keeping in mind if you are thinking of traveling great distances to experience local color: get confirmation of the festval’s dates from the Tourist Office before you set off.

Those that take place with fair regularity and that are very much worth a visit are as follows:

This festival in the south of Morocco is a pleasant diversion from the swarming beaches of Agadir, lined with Europeans in search of a winter tan.

This remote village hosts an unusual collection of local-design beehives, made from split reed cylinders and clay. A little off the beaten path, but a must-see for beekeepers.

The festival takes place around the time that cultivated Centifolia roses, used in the production of rosewater and perfumes, are harvested. A true feast for the senses.

Cherry trees in blossom provide the backdrop for the usual sorts of Moroccan merry-making: a fantasia, sporting competitions, and lots of good food.

This is now actually a transnational folklore festival, with musicians from across the Arab world and beyond. All the usual suspects accompany the crowds: folk singing and dancing, community events, crafts, costumes, jewelry, and of course, food.

This festival attracts performers of sacred music from around the world, performed in mostly ancient venues.

This colourful festival, featured in National Geographic and other outlets, is about to become a victim of its own success. Not so easy to get to, but worth the trek.

A million date palms supply the subject of this festival in the south of Morocco. An opportunity to sample more kinds of dates than you knew existed.

Hundreds of horses mounted by riders in traditional garb compete in fantasias and other events. This is the one to hit if you miss the similar fantasia festival in Meknes in September.