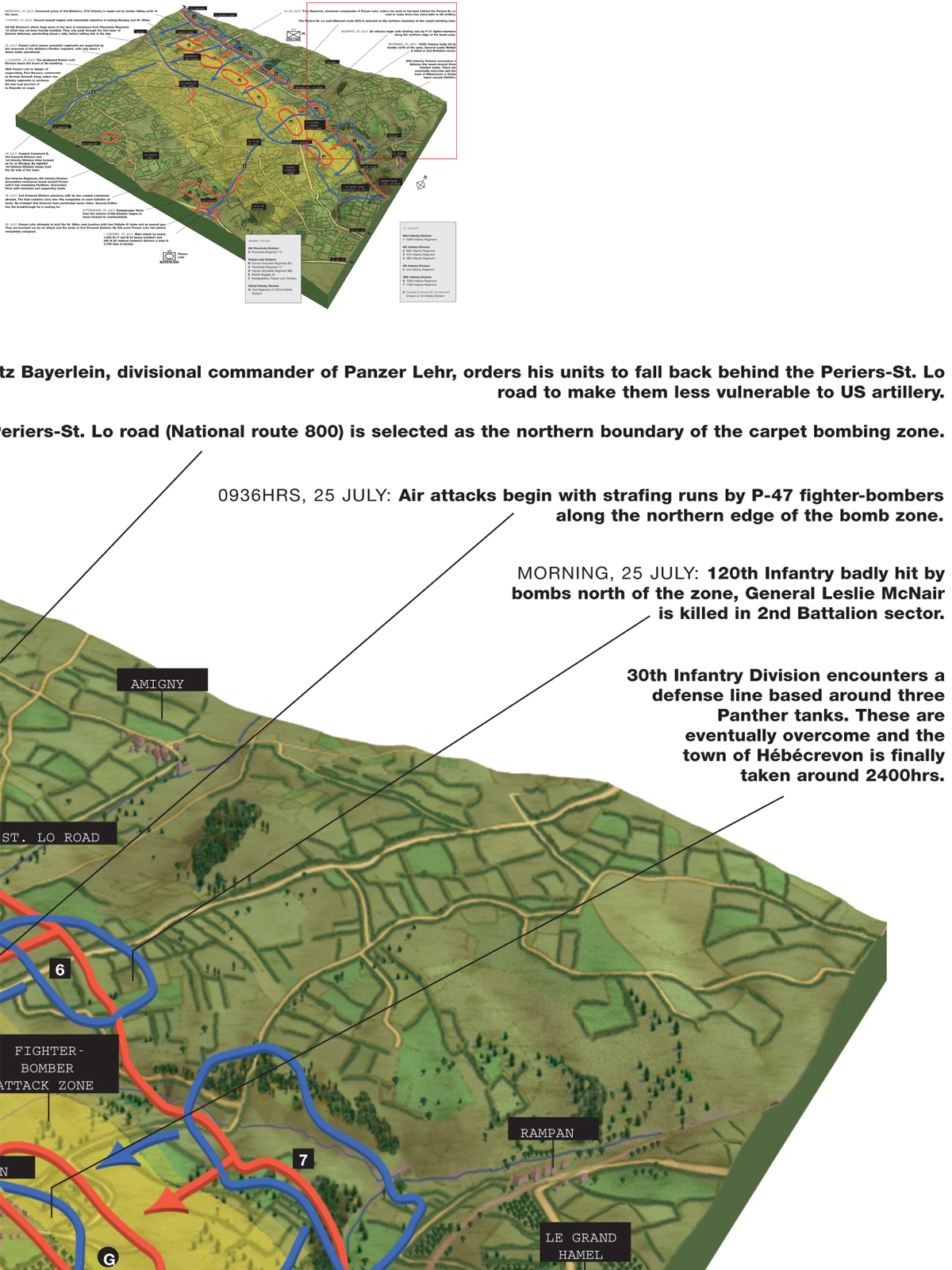

Operation Cobra was scheduled to begin at 13.00hrs on 24 July 1944 with the heavy bomber attack. The attack was cancelled late in the morning due to heavy overcast conditions over the battlefield. The message to halt the mission arrived after the heavy bombers were already airborne. Three of the six fighter-bomber groups received the recall message, but the others conducted their missions along the northern edge of the bomb zone. The first 500 heavy bombers of the 1,600 dispatched found the area so obscured by clouds that they returned to England. Another 335 bombers dropped 685 tons of bombs. The lead bombardier of one unit accidentally released his payload prematurely, and was followed by the fifteen other aircraft of his formation. These fell 2,000 yards north of the bomb zone, killing 25 men of the 30th Division and wounding a further 131.

The friendly casualties from the bombing caused a major dust-up between Bradley’s staff and the air commanders. Bradley was under the impression that the air force commanders would stage the bombardment parallel to the Periers–St. Lô highway not perpendicular to minimize the chance of casualties. The air force disagreed, fearing heavy losses to flak since the bombers would be flying unusually low – only 15,000 feet. Bradley was also concerned that the aborted bombing mission would alert the Germans to the planned offensive and lose the element of surprise. In fact it had little impact on Hausser’s plans since he had so few resources anyway. Weather forecasts for the following day seemed better and Bradley ordered the air attack to take place on 25 July.

Operation Cobra started with a devastating carpet–bombing of a section along the D900 Periers-St. Lô road by 1,495 B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers. This is one of the few known photos of the mission from Patton’s personal collection. The view looks to the west, and the bomb impacts in the lower left of the photo are covering the area around Chapelle-en-Juger near the intersections of Routes D900 and D972. A B-24 Liberator bomber appears at the top of the photo. (Patton Museum)

Panzer Lehr Division had weathered the first air attack with modest casualties – about 350 men and 10 armored vehicles. The division’s commander, Fritz Bayerlein, was convinced that his forces had repulsed a major US attack. In anticipation of more fighting, he ordered his forward outpost line from positions north of the Periers–St. Lô highway to the south where they would be less vulnerable to US artillery. This placed them immediately inside the most intense sector of the bomb zone the next day. The aborted 24 July attack confused German higher headquarters. While Hausser reiterated his concern that the Americans planned a significant action in his sector, he did not seem unduly alarmed in a conversation with Kluge. As a result Kluge continued his inspection of Panzer Group West on 25 July.

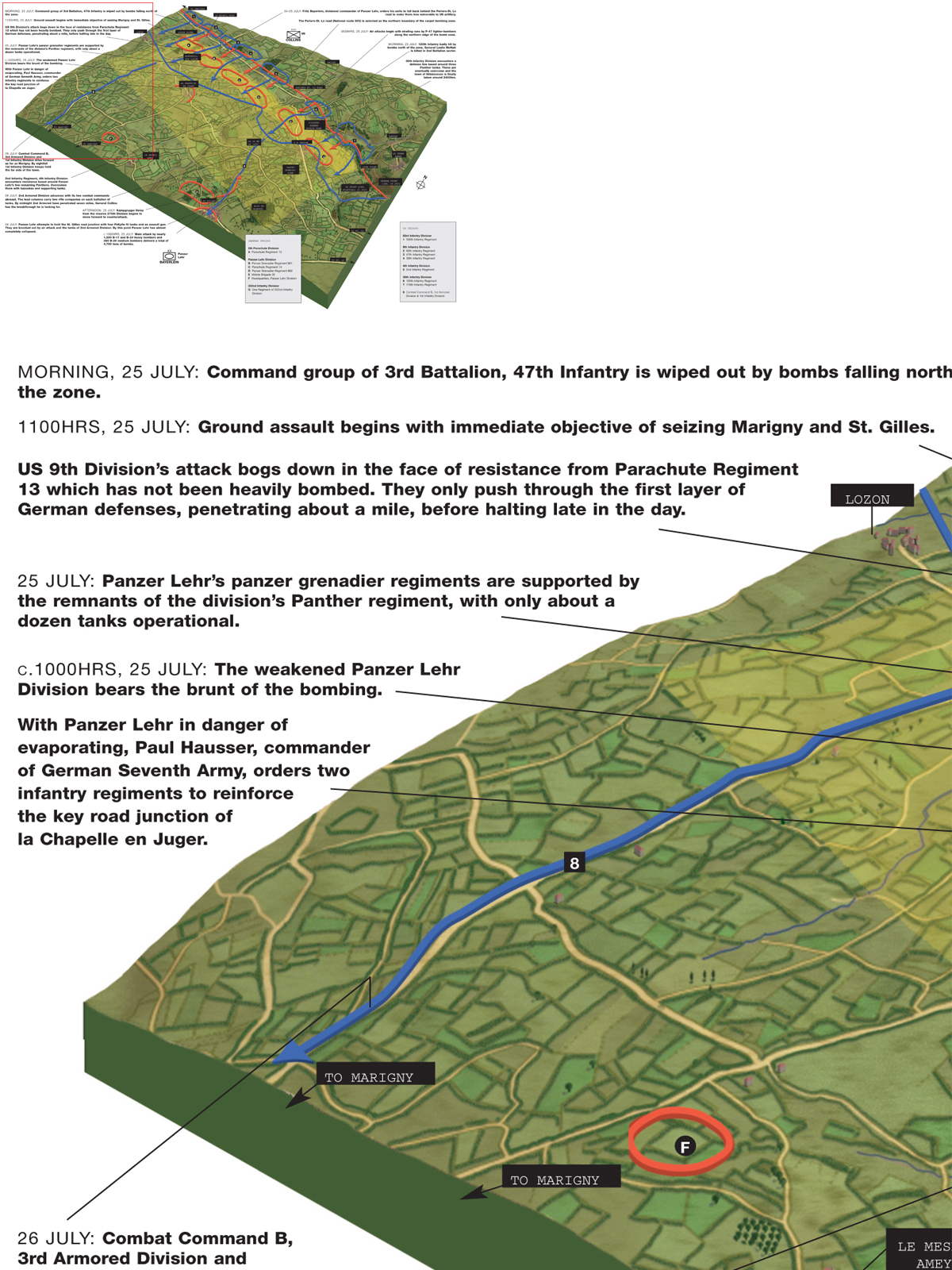

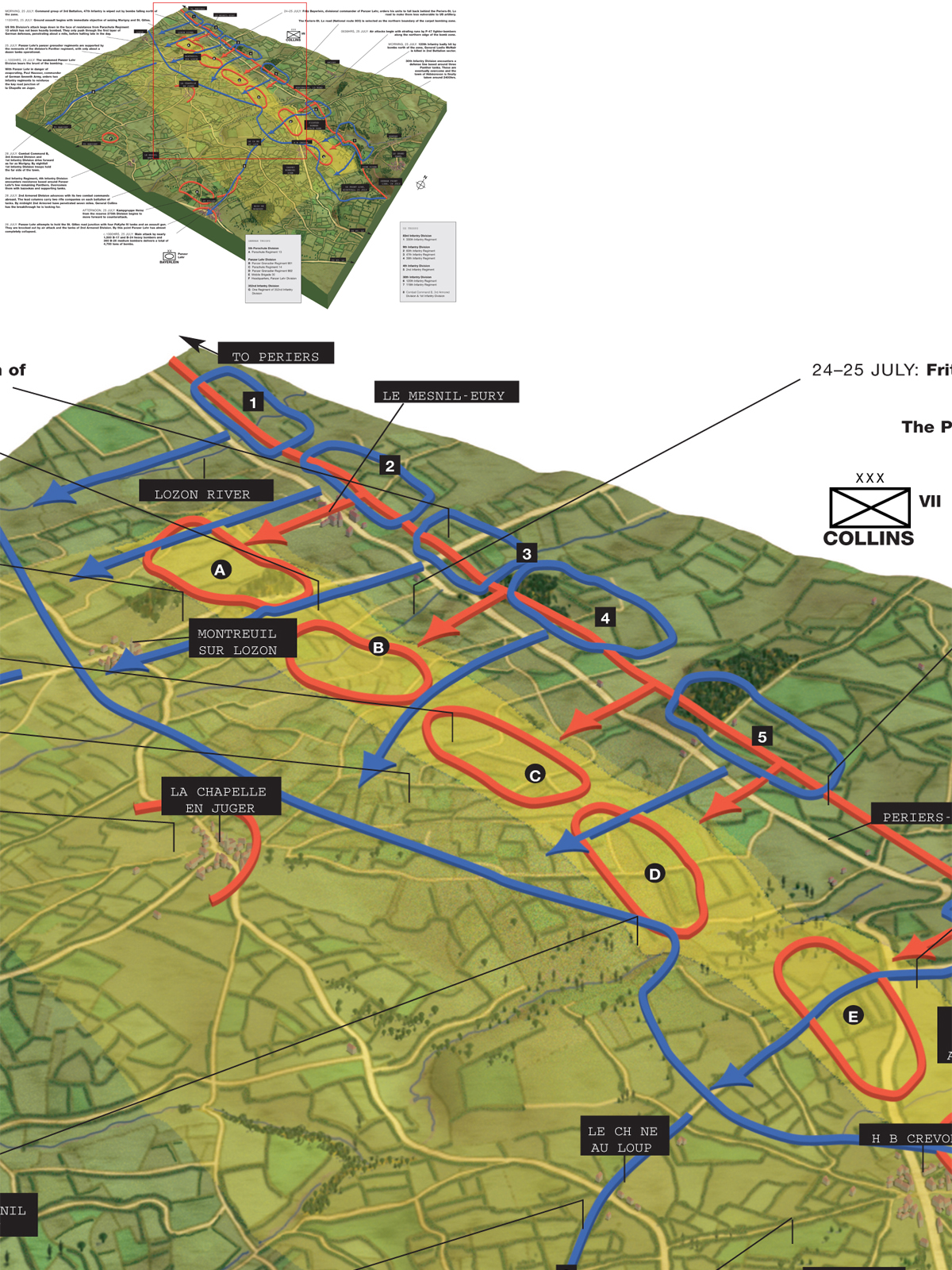

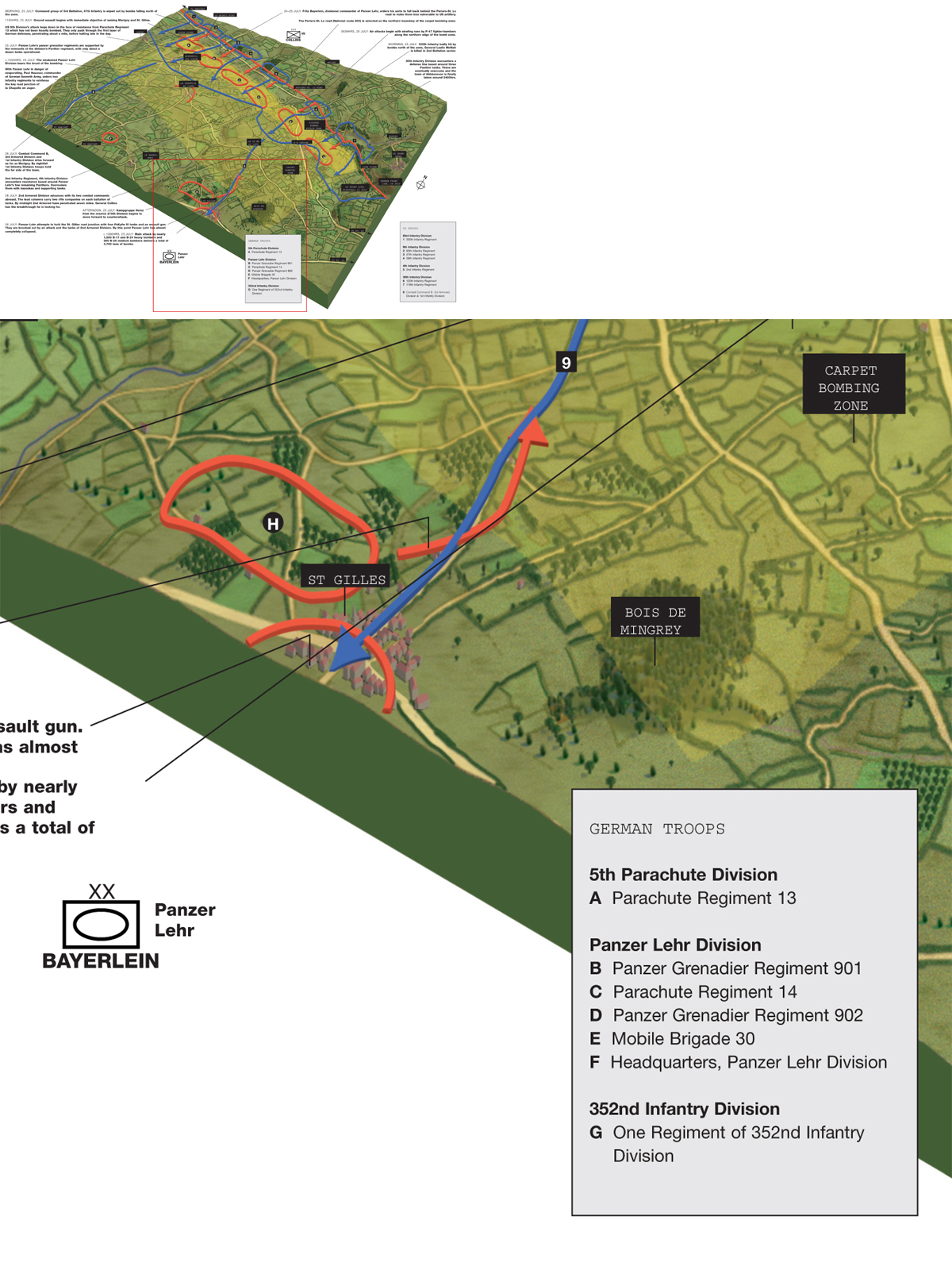

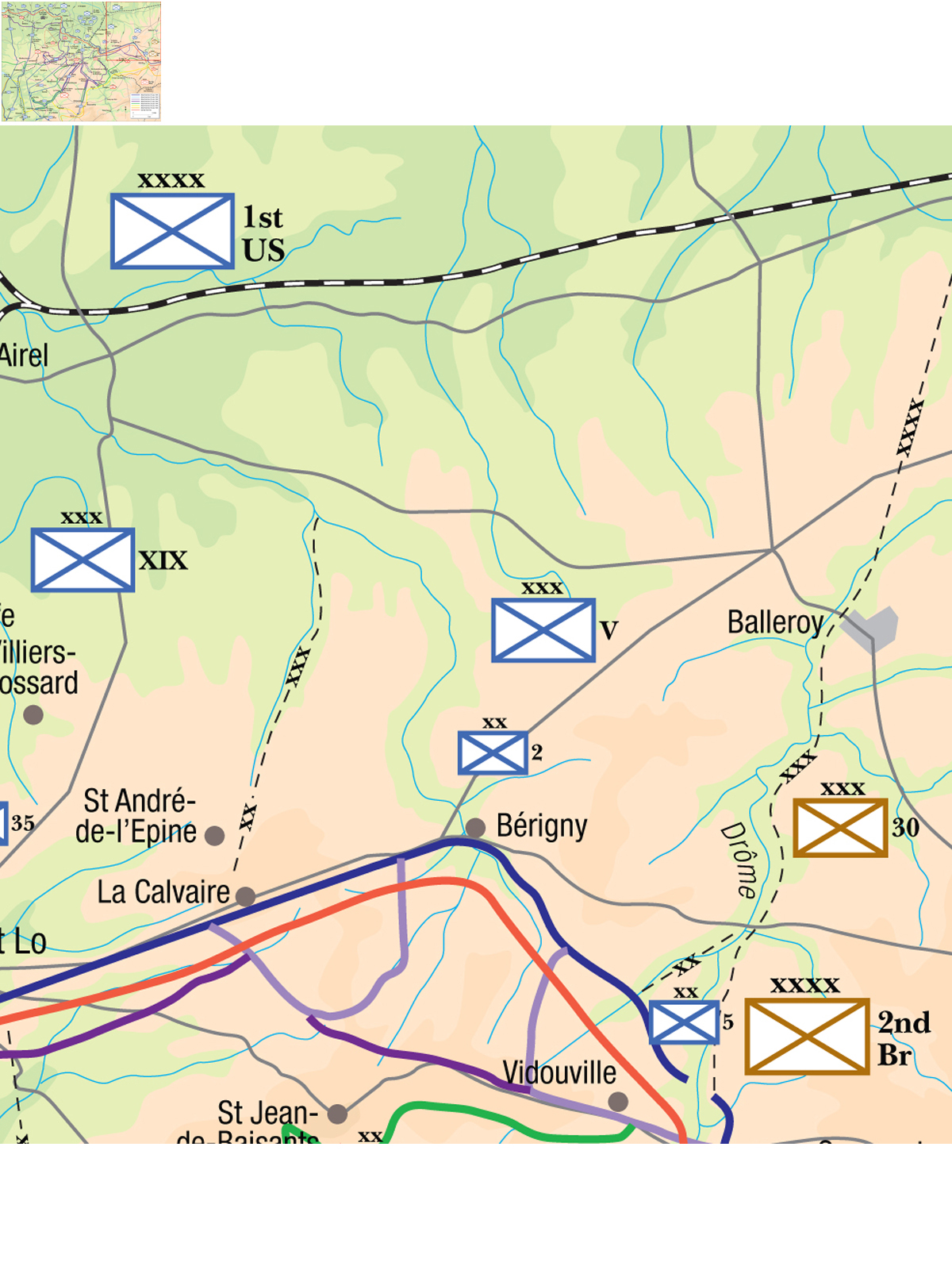

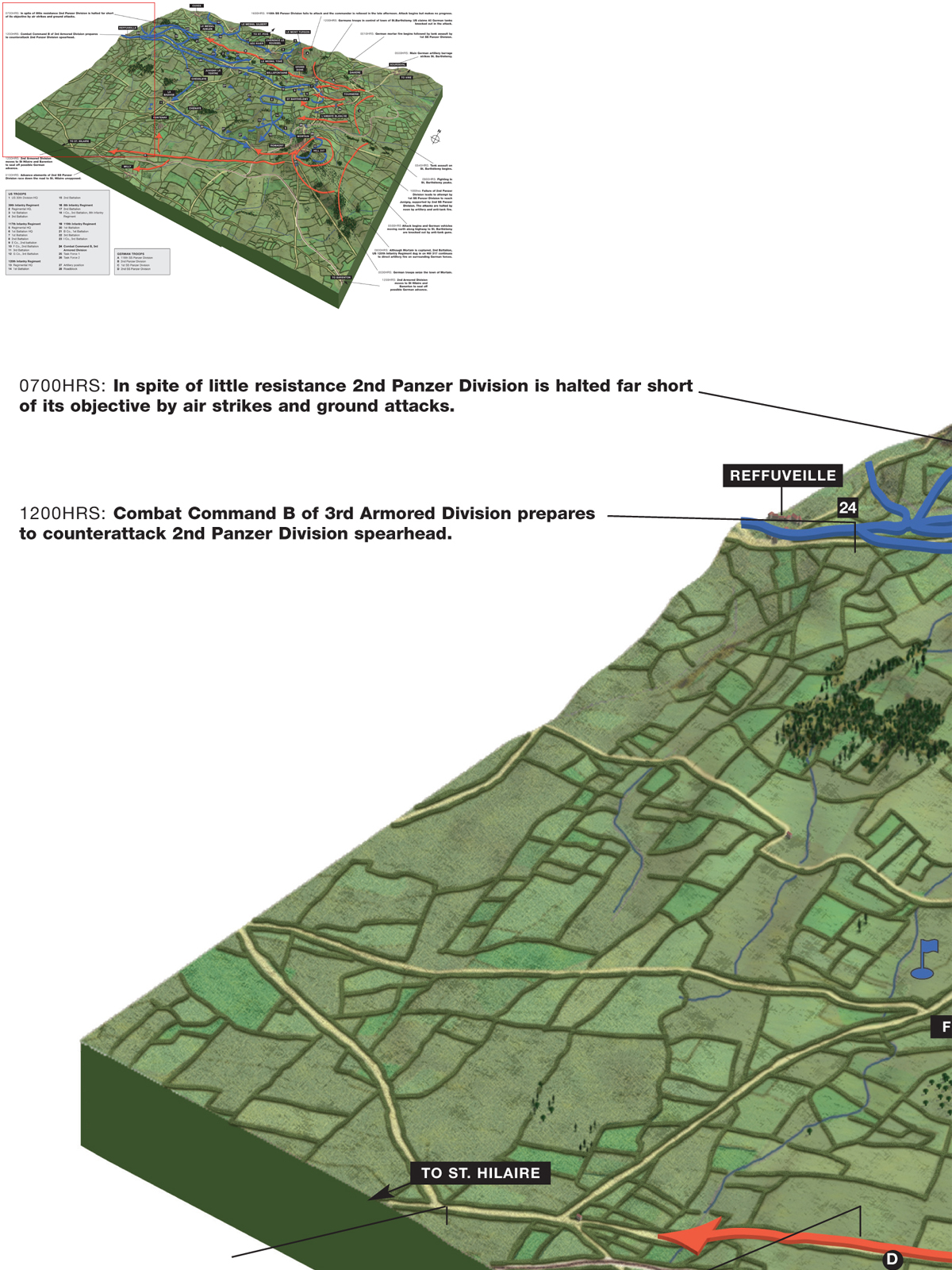

25–26 July 1944, viewed from the south east, showing the initial devastating bombing attacks, the US attacks of 25 July and the breakthrough on 26 July

The carpet-bombing that preceded Operation Cobra knocked out several of the Panzer Lehr Division’s Panther tanks that had been deployed near the Periers–St. Lô road. This Panther Ausf. A has received one bomb strike on the right front corner of the hull roof, and has slid into a bomb crater.

The air attack on 25 July started at 09.36 with strafing runs by P-47 fighter-bombers along the northern edge of the bomb zone. They were followed by 1,495 B-17s and B-24 heavy bombers in several waves, dropping 3,370 tons of bombs into an area 7,000 yards long and 2,500 yards wide. A further 380 B-26 medium bombers completed the attack, bringing the grand total to 4,700 tons of bombs. Anti-aircraft fire was light, and a number of anti-aircraft guns were destroyed by US artillery counter-fire.

The effect on the German defenses was devastating. Of the 3,600 troops under Panzer Lehr Division’s immediate control, about 1,000 were killed in the bombing attack, and at least as many wounded or severely dazed. The German communications network, which depended heavily on field telephones, was completely disrupted. The only combat effective unit available to the division by late morning was Kampfgruppe Heintz, which was stationed to the south-east outside the bomb zone. But the bombing coverage was patchy. The damage was worse in the center of the bomb zone where the heavy bombers had struck, while some defensive positions closer to the American lines – including about half the tanks – had gone unscathed.

Troops of the 47th Infantry, 9th Division move through a breach in the hedgerow created by a dozer tank on 25 July. The 9th Division had suffered significant casualties in the preceding weeks and lacked tank support during the initial breakthrough attempt.

A day after the initial attack, GIs inspect some of the equipment abandoned by the Panzer Lehr Division along the Periers–St. Lô road after the carpet-bombing. In the foreground is a SdKfz 251/7 armored half-track fitted with engineer bridging equipment, with a disabled Panther Ausf. A behind it. A half-dozen Panthers survived the initial bombing but were quickly overwhelmed by the ensuing infantry attack.

The 25 July air attack repeated the problems of the previous day, with bombs again falling short into American lines, killing 111 and wounding 490 soldiers. Among them was Lieutenant General Lesley McNair, head of Army Ground Forces, the highest ranking US officer to die in the war. The casualties were especially severe in the forward assault companies, causing significant problems in launching the initial attacks.

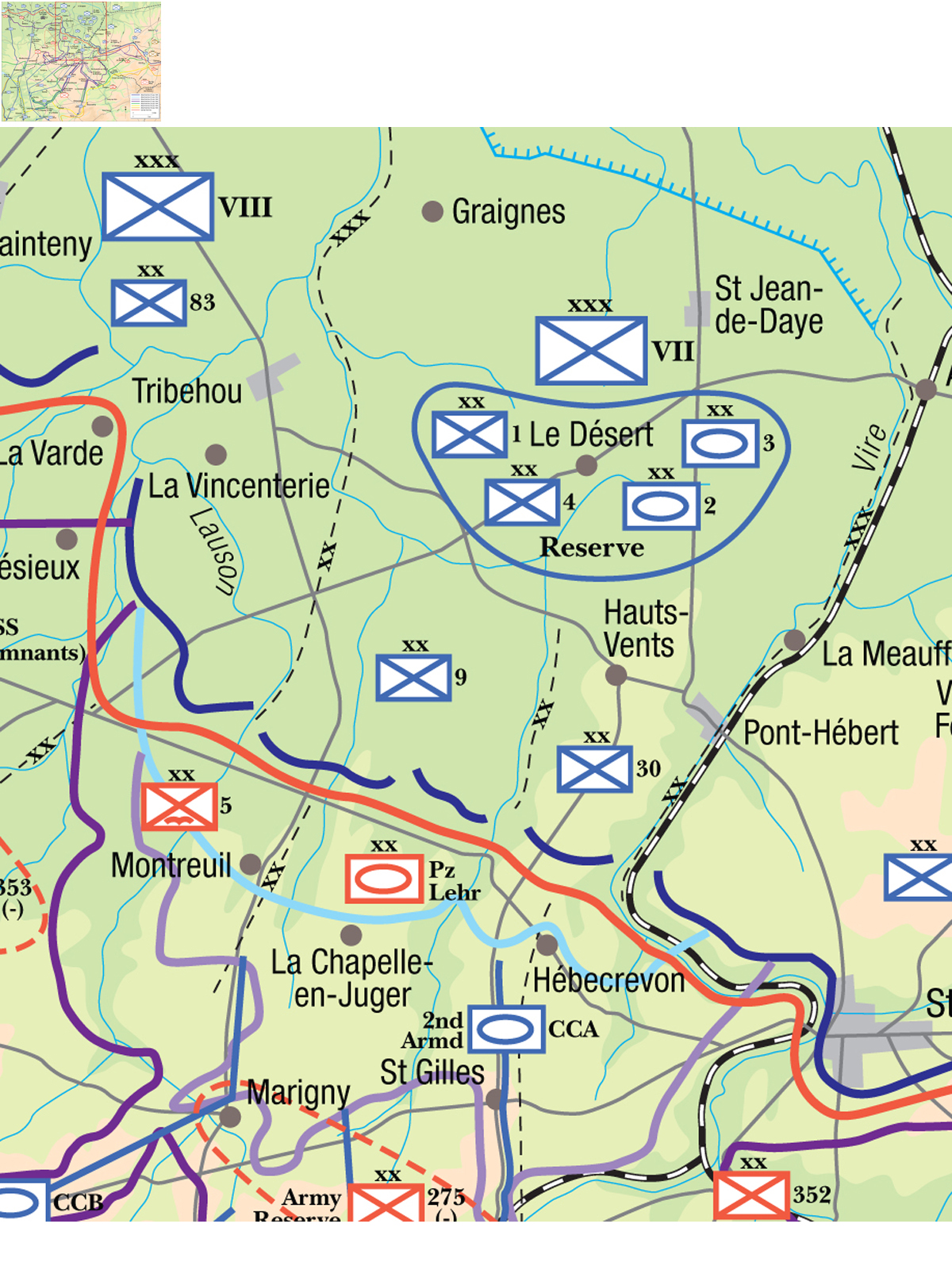

In spite of the bombing errors, the ground attack began at 11.00 with the immediate objective of seizing Marigny and St. Gilles about three miles from the start line. The western portion of the attack bogged down quickly as the defensive positions of Parachute Regiment 13 of 5th Parachute Division had not been heavily bombed. Eddy’s 9th Division was surprised to find continued German resistance, and only managed to push through the first layer of the German defenses before halting late in the day. A single regiment from the 4th Division encountered a defensive position based around the few remaining Panther tanks of Panzer Lehr Division, but overcame them with bazookas and supporting tanks. Likewise, the 30th Division encountered a defense line based around three Panther tanks, which was eventually overcome. The town of Hébécrevon was finally taken at midnight.

Overall, the first day’s attack had been disappointing. Instead of gaining three miles, Collins’ VII Corps had only penetrated about a mile. The option was to continue the infantry attack for the next few days in hopes of securing a clean penetration, or act more boldly and commit the mechanized forces the next day. Collins decided on the bolder option. This was based on his assessment that the German defenses were in a shambles. Previously when US forces in Normandy advanced as far as a mile into German positions, they would inevitably be met with fierce, coordinated counterattacks. Instead there was very little evidence of any coordinated response. Collins also realized that too little force had been used in some sectors, notably the tired 9th Division which had no armor support. This would be rectified the next day. The main problem of deploying armor at this stage was congestion on such a narrow front.

By the end of the day Bayerlein reported to Hausser that he had no infantry left and that his division was on the verge of evaporating. Two infantry regiments from the reserve were ordered forward to reinforce the defenses at the key road junction at Chapelle-en-Juger, and Hausser committed his modest panzer reserves, a couple of companies of the 2nd SS Panzer Division. Hausser’s failure to build up an adequate reserve was now plainly obvious, as was Kluge’s failure to address the deficiencies. On learning of the numerous penetrations of the line, Kluge placed an urgent request to the high command for transfer of the 9th Panzer Division from southern France. It would take ten days to move it to the Cotentin area due to Allied air activity. The immediate focus was on plugging the breach.

THE CARPET-BOMBING ZONE, 25 JULY 1944

Panzer Lehr Division had its 16 operational Panthers “strung like a necklace of pearls” through its forward edge of battle on the morning of 25 July when Operation Cobra struck. Most of the tanks were caught in the initial bomber attack, and were disabled. As often as not, the near misses on the tanks ripped off tracks, killed the crews, or otherwise disabled the tanks. Few tanks suffered the direct hits needed to put them completely out of action. But in the chaos of the attacks, there was neither the time nor resources to repair damaged vehicles. This battlescene shows two disabled Panther tanks moments after the air attack with the injured crews being assisted by divisional medics and other panzer crews. In spite of the intensity of the bomber attack, several Panther tanks remained in action until knocked out during the ensuing infantry assault. (Tony Bryan)

A GI from the 83rd Division takes cover behind a destroyed Schwimmwagen during the start of Operation Cobra on 25 July. The Schwimmwagen was an amphibious version of the Volkswagen Kubelwagen light utility vehicle, and was commonly used in panzer formations. The markings on the back end of the vehicle identify it as belonging to the engineer battalion of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division.

Collins’ exploitation force consisted of the 2nd Armored Division to the east, and the 1st Infantry Division reinforced by Combat Command B (CCB) of the 3rd Armored Division in the west. CCB/3rd Armored led the attack towards Marigny. One of the main problems was traffic congestion and the poor state of the bombed roads. Passing an armored formation and an infantry regiment down narrow country roads, already occupied by the 9th Division, proved difficult. The new dozer tanks proved to be a big help. The armored attacks on 26 July were preceded by 200 sorties by P-47 fighter-bombers against the two key towns of Marigny and St. Gilles. The air attacks inflicted serious losses on regiments of the 353rd Division that Hausser had sent to counterattack. By late afternoon, the CCB/3rd Armored Div. was on the outskirts of Marigny where it was counterattacked by two companies from 2nd SS Panzer Division and the remnants of a regiment from 353rd Division. The attack halted for the night with the 1st Division infantry holding the other side of Marigny.

The first objective to fall into US hands was the village of Hébécrevon, which fell to the 30th Division around midnight of 25 July. Here a column of infantry from the 1st Battalion, 120th Infantry, 30th Division pass through the devastated village the next day. In the center is a M29 tracked utility vehicle.

A column from the 33rd Armored Regt., 3rd Armored Division prepare to move forward from the village of Montreuil-sur-Lozon on 26 July. The CCB of the 3rd Armored Division was committed that day to support the attack of the 1st Infantry Division. The vehicle at the head of the column is a M8 75mm howitzer motor carriage, a variant of the M5A1 light tank used as an assault gun in light tank and cavalry units.

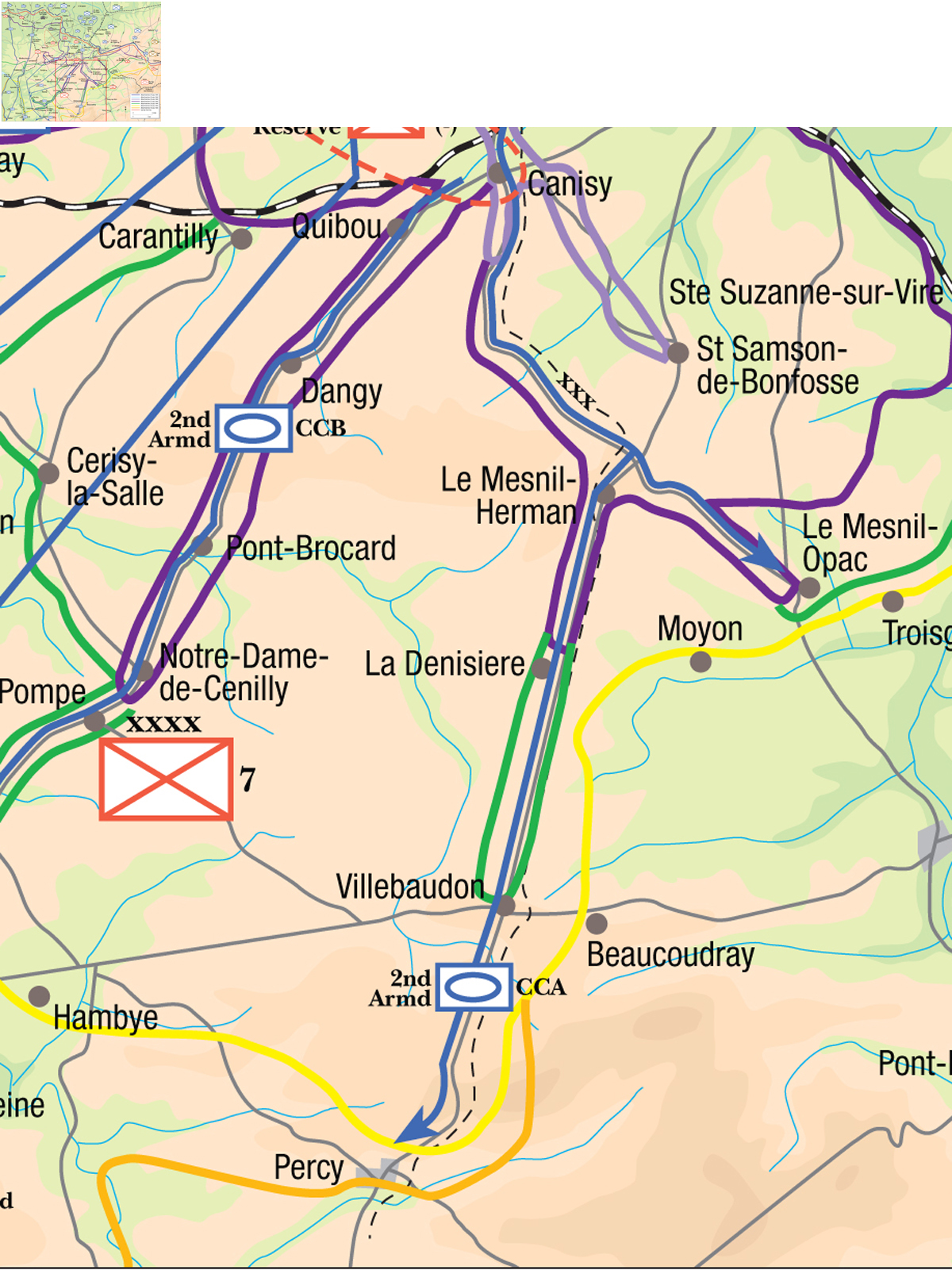

The eastern spearhead by the 2nd Armored Division moved much more rapidly, with its two combat commands abreast. In order to speed the advance the lead tank columns carried two rifle companies on each battalion of tanks – about eight GI’s per tank. Panzer Lehr Division attempted to defend the road junction at St. Gilles with four PzKpfw IV tanks and an assault gun, but two of the tanks were knocked out by air attack and the remainder by the tank column. By midnight, the 2nd Armored Division had penetrated seven miles for the loss of three tanks, due in large measure to the 30th Division’s earlier efforts and the almost total collapse of the Panzer Lehr Division. By late afternoon, Collins was convinced that the penetration had been made and that German defenses were crumbling. He ordered the attack to continue through the night, with an emphasis on speed over caution.

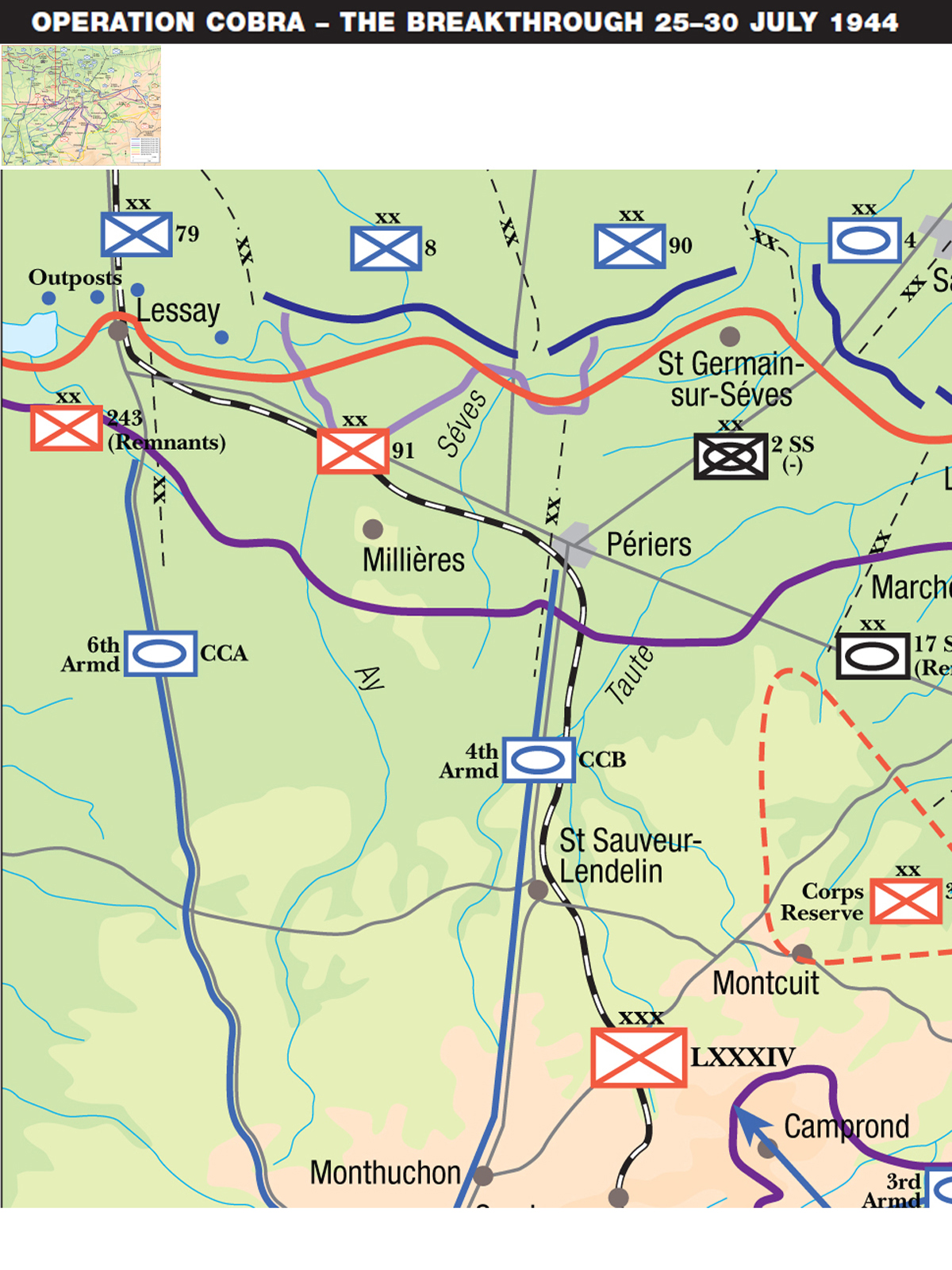

Collins next decision was whether to proceed with the planned “right hook” towards Coutances, the aim of which was to bag the western elements of the German Seventh Army. In spite of not yet holding the road junction at Marigny, Collins ordered the attack anyway, with a regiment of the 1st Infantry Division assigned to take the town. Early on the morning of 27 July, CCB/3rd Armored Division sent three task forces, each consisting of a company of M4 tanks and a company of armored infantry in M3 half-tracks, down the Coutances road. One of the groups ran into an ambush by a Panther tank from 2nd SS Panzer Division commanded by Ernst Barkmann. Three M4 tanks were quickly knocked out, but Barkmann’s Panther was damaged by tank fire and supporting air cover and withdrew. The incident was wildly exaggerated by German propaganda, and has acquired mythic status in recent accounts of the Normandy campaign in spite of its insignificance. The CCB/3rd Armored Division task forces advanced four miles in four hours, and by mid-afternoon reached its objective at Camprond. The 2nd Armored Division continued its advance in spectacular fashion, with CCA exploiting the weakness along the German corps boundary, and plunging further south beyond Pont Brocard. Equally important the US VIII Corps had begun its offensive in the western sector, pushing south of the Periers road and taking the town of Periers against relatively light resistance.

THE BREAKTHROUGH

Although the 2nd Armored Division had fitted Culin hedgerow cutters to nearly three-quarters of the tanks in the assault waves, they were not as widely used as the legend would suggest. Once the infantry had penetrated the shattered defenses of the Panzer Lehr Division, the 2nd Armored Division rapidly exploited gaps in German defenses. When possible, the tank units preferred to use country roads for speed. The armored column cover provided by P-47 Thunderbolts of the 9th TAC was essential in such tactics since the fighter-bombers could provide armed reconnaissance in front of the advance. If German defenses were encountered, they could be bombed and strafed before the tanks arrived. The tanks here are the M4 medium tank with 75mm gun, the most common type in service in July even though about 100 of the newer type with 76mm gun had arrived for the offensive. The First US Army adopted a camouflage pattern of black over olive drab during the Normandy fighting, and the prominent white Allied star insignia were usually painted out for fear of acting as a prominent target for German anti-tank gunners. (Tony Bryan)

Hausser quickly appreciated that the Americans were trying to tie down the 84th Corps and then envelope it from behind by seizing Coutances. He began steps to withdraw the exposed 84th Corps south to the Geffosses–St.Saveur–Lendelin road. Permission to withdraw was delayed, as Kluge was still in the Caen sector until late in the afternoon of 27 July but he was finally reached. However, neither Kluge nor Hausser had any idea of how calamitous the situation was in the Panzer Lehr sector. In addition to the 9th Panzer Division, Kluge received Hitler’s permission to transfer three infantry divisions from the Pas de Calais.

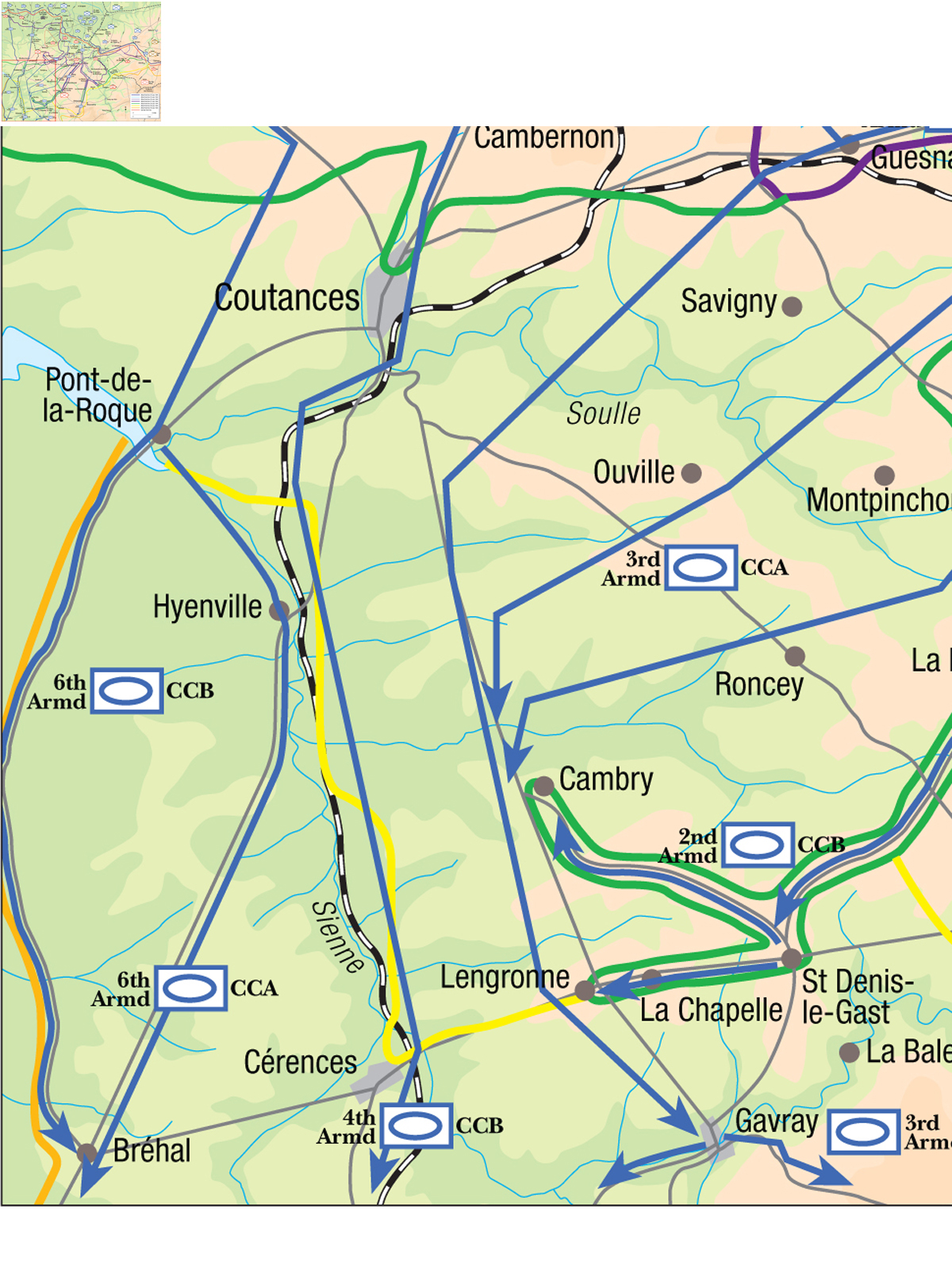

The attacks on 28 July 1944 undermined the orderly German withdrawal. With the 84th Corps retreating towards Coutances, Middleton’s VIII Corps unleashed its two fresh spearheads, the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions. By nightfall the 4th Armored Division was at the doorsteps of Coutances after facing little opposition. In the center Collins released CCA of 3rd Armored Division, which rushed through the Marigny–St. Gilles gap to Cerisy-la-Salle. The most impressive performance was again by the 2nd Armored Division. It’s CCB raced down the highway past St. Denis-le-Gast, cutting the road south out of Coutances near Lengronne and Cambry. It’s CCA continued its mission of forming an eastern shield for the Cobra operation, reaching Villebaudon.

By late afternoon on 28 July it was becoming apparent to Dietrich von Choltitz, the 84th Corps commander, that his forces were on the verge of being encircled. American patrols were penetrating deep behind German lines, often in the most unexpected of locations. The 2nd SS Panzer Division commander was killed by a US patrol near his command post, and Hausser himself was almost captured by another US patrol. Command of the 2nd SS Panzer Division and 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division fell to Lieutenant Colonel Otto Baum. He discussed withdrawing the remnants of the units southward along the coast road towards Brehal, where they could avoid the westward-moving US forces, and Choltitz agreed. Hausser had other ideas and decided that it would be better for the 84th Corps to withdraw to the south-east, towards Percy. His rationale was that this force would be in place to support Kluge’s planned counterattacks with new units from the Vire river aimed at stopping the US penetration. Choltitz protested strongly, arguing that this would denude the coastal area of major forces, allowing the Americans to plunge south along the coast, and envelop the corps from the west as well. Furthermore, it would force the corps to run the gauntlet of the US divisions now starting to move westward to the coast. Hausser told him to follow orders, and notified Kluge of his plans. Kluge was apoplectic about Hausser’s plans. Lacking radio contact, he sent a courier to Hausser insisting that the plans be cancelled and the retreat directed south to Brehal as Choltitz had suggested. By the time that Hausser passed on the orders to Choltitz around midnight, the damage had been done as Choltitz no longer had any lines of communication with the retreating units. The bulk of these forces were located around Roncey and Montpinchon, and began to move towards Percy in the early morning hours.

The CCA, 2nd Armored Division reached the road junction at Canisy by the late afternoon of 26 July after part of the town had been set ablaze by an air attack. There was little resistance from the shattered Panzer Lehr Division. This is an M8 armored car of the division’s 82nd Recon Bn.

Although the Panther battalion of Panzer Lehr Division was caught in the initial Cobra bombing attack, the PzKpfw IV battalion was recuperating in the rear. Nevertheless, the battalion lost most of its tanks like this one during skirmishes with the 2nd Armored Division in the ensuing days. Of the 70 in service at the beginning of July it had only 15 PzKpfw IV left by 1 August.

Collins and the other American commanders expected that the Germans would probably try to break out of the encirclement that evening, and warned their forward patrols. The thinly stretched CCB of 2nd Armored Division was reinforced by the divisional reserve. One German column of about 30 tanks and armored vehicles, led by a Hummel 150mm self-propelled gun, attempted to drive through the crossroads south-west of Notre-Dame-de-Cenilly before dawn. The position was held by a company of armored infantry and some M4 tanks of the 2nd Armored Division. A close-range melee ensued, and when dawn came the Americans still held the crossroads. Along the same road, another column of about 15 PzKpfw IV tanks from the 2nd SS Panzer Division supported by about 200 paratroopers of the 6th Parachute Regt. overran an outpost recently established by a company of the 4th Division at La Pompe. The US infantry fell back to the positions of the 78th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Two batteries of M7 105mm self-propelled guns, supported by four M10 tank destroyers held back the German attack with direct fire until reinforced by an armored infantry company. Although small groups of German infantry managed to infiltrate past the US outposts in the dark, their failure to seize any of the key road junctions left the bulk of the 2nd SS Panzer and 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Divisions trapped on the narrow country roads around Roncey. Many of the vehicles were low on fuel, further complicating the retreat.

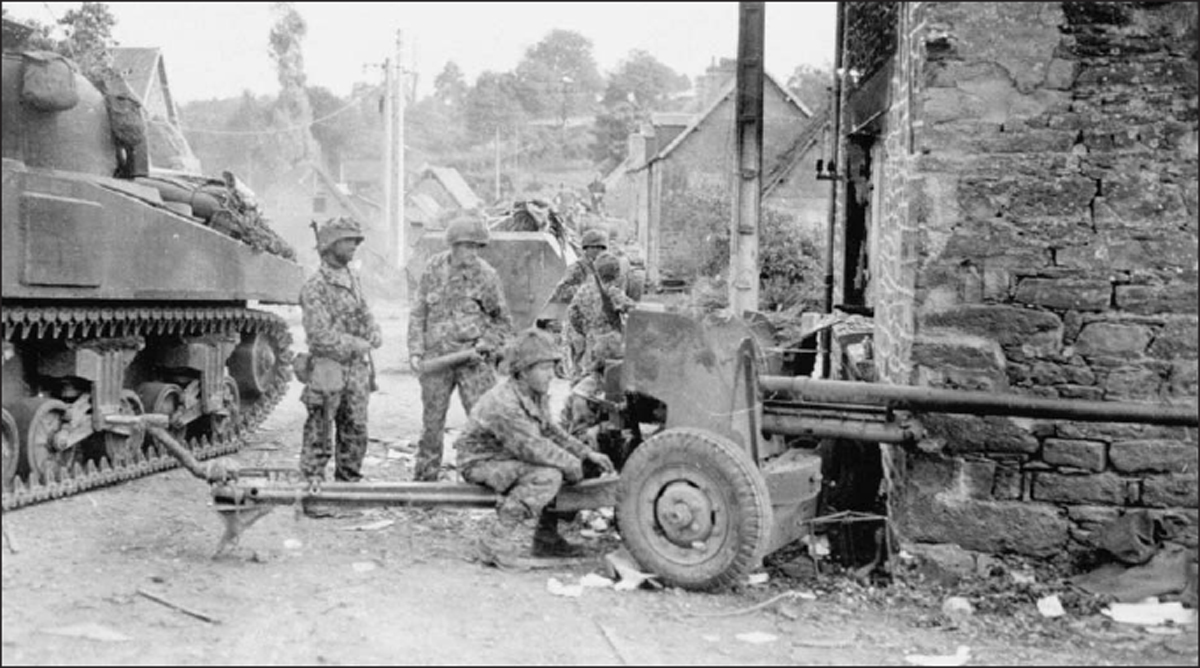

Lead elements of the CCB, 2nd Armored Division seized the bridges over the Soulle river at Pont Brocard on 27 July, nearly capturing the commander of Panzer Lehr Division in the process. Here a 57mm anti-tank gun is stationed at a road junction in the town on 29 July as a M4 medium tank passes by. The 2nd Armored Division was one of the few US units to wear camouflage battle-dress during Cobra, a practice which ended in August due to frequent confusion with German camouflage clothing.

The next day P-47 Thunderbolts of the 405th Fighter Group arrived to discover a “fighter-bomber’s paradise” of about 500 vehicles jammed together. From mid-afternoon to nightfall, the fighter-bombers pummeled the columns. A total of 122 tanks, 259 other vehicles and 11 artillery pieces were later found destroyed or abandoned in the “Roncey pocket”. A separate strike by British Typhoons near La Baleine knocked out nine tanks, eight armored vehicles, and about 20 other vehicles. Cautiously moving southward with the vehicles that still had fuel, the German troops planned another escape attempt when darkness fell. For a second night there was a series of desperate close-quarter battles as the German troops tried to escape between gaps in the US outposts. The most vicious was an attack by about a thousand German infantry supported by several dozen assorted armored vehicles against St. Denis-le-Gast. By morning the attack had been crushed at a cost of 130 German dead, 124 wounded and 500 prisoners as well as 7 tanks and 25 armored vehicles. US losses were 100 men and 12 vehicles, including the commander of the 41st Armored Infantry, LtCol Wilson Coleman, who was posthumously decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership in the battle.

Eleven vehicles of the assault gun battalion of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division escaped westward from St. Denis-le-Gast, and during the night stumbled into the 78th Armored Artillery near La Chapelle supported by an M10 tank destroyer. In the ensuing melee, the M7 self-propelled guns knocked out the lead vehicles at point blank range with 105mm howitzer fire while a M10 tank destroyer knocked out the trailing vehicle. Silhouetted by the flames of the burning vehicles, the remaining German armored vehicles were destroyed leaving 90 dead and 200 prisoners.

The key road junction at Marigny was the objective of the 9th Division on the first day of Operation Cobra. However, it did not finally fall until the morning of 28 July to the reinforced 1st Infantry Division. The German signs on the electrical post give directions to neighboring units, including Kampfgruppe Heintz.

Another force of about 2,500 Germans tried to overrun a road-block on the Coutances highway near Cambry. Supported by an M4 tank, the US infantry broke up the attack and called in artillery fire. After six hours of confused fighting the German column had lost 450 dead, 1,000 prisoners and about 100 vehicles. By daybreak the German escape attempts were largely spent at a cost of about 1,500 dead and 4,000 prisoners against US losses of about 100 dead and 300 wounded. Heroic actions during these night battles led to the award of one Medal of Honor and three Distinguished Services Crosses to soldiers of the 2nd Armored Division. Most but not all of the German force had been destroyed. A battalion of PzKpfw IV tanks from 2nd SS Panzer Division escaped, along with elements of the 17th SS Pz.Gren. Div. and 6th Parachute Regiment. The only unit to maintain any semblance of order was the 91st Division, which had retreated down the coast away from the American outposts as Choltitz had originally planned. Hausser’s most powerful formation at the start of Cobra, the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich”, had been nearly annihilated with nothing to show for its losses.

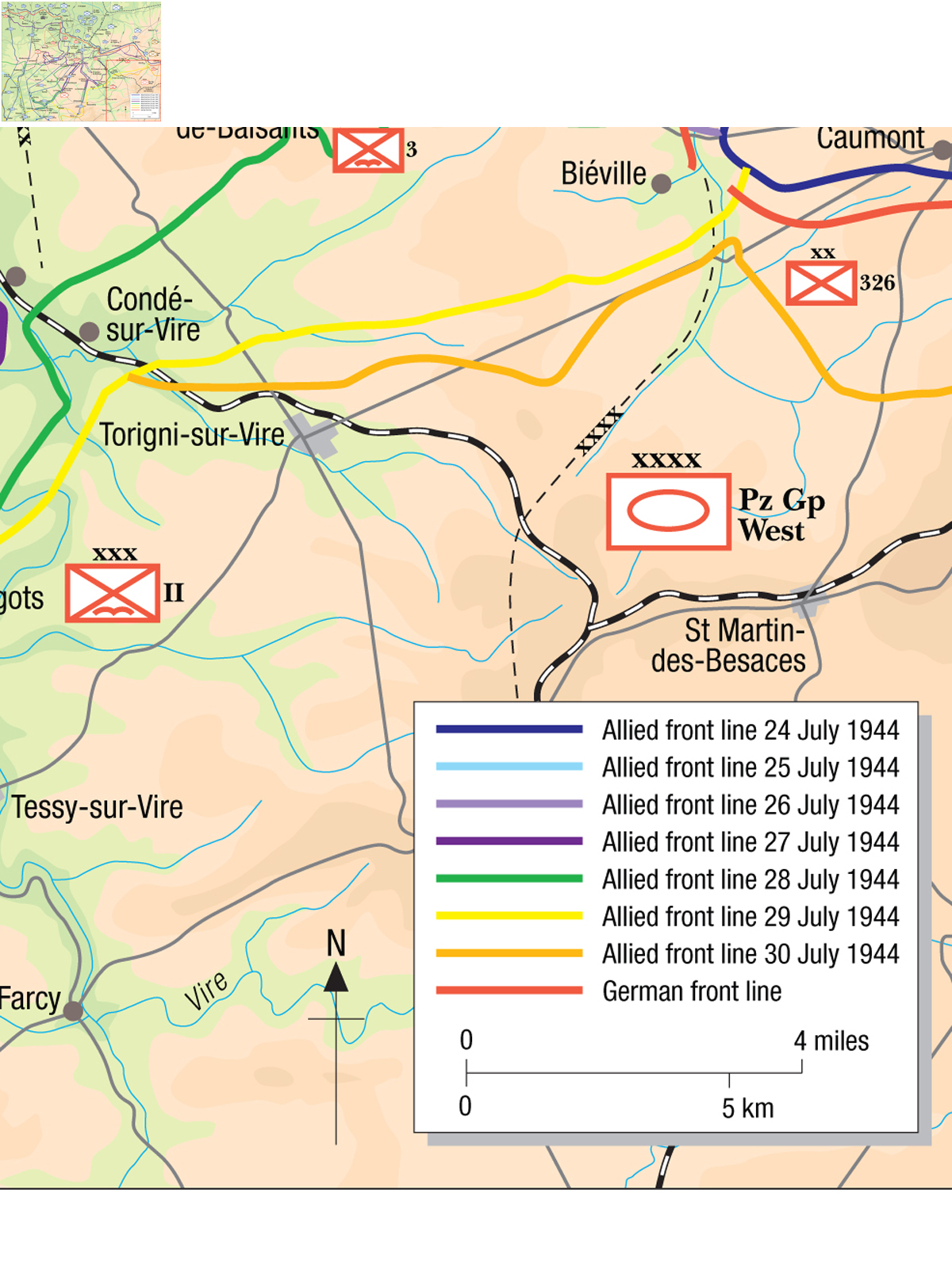

In the midst of this debacle Kluge was struggling to put together a counterattack force, but the growing disarray in the Seventh Army undermined plans before they could be completed. The 9th Panzer Division would not be available for at least ten days, so Kluge decided to shift the 2nd Panzer Division and the 116th Panzer Division from the British sector to the Cotentin region. Kluge hoped to use the two armored units to plug the gaping hole in the front, and to reestablish a defensive line from Granville on the coast through Gavray, Percy, Tessy-sur-Vire and Caumont. The lead elements of the 2nd Panzer Division crossed the Vire river and began taking up positions north of Tessy-sur-Vire on 28 July. The panzer force was able to stymie further advances by Corlett’s XIX Corps near Troisgots, but quickly became bogged down resisting the US infantry attacks. On 30 July the 116th Panzer Division arrived, and was committed to the south-western edge of Collins’ VII Corps, resisting any further advance east by the 2nd Armored Division from Villebaudon and Percy. Although the two divisions did limit the eastward advance of VII and XIX Corps on 29–30 July, they did not have the strength to carry out their main mission of sealing the gap. By 28 July Kluge had lost all hope of stabilizing the defenses around Coutances. By the end of July the First US Army had captured about 20,000 German troops and had effectively destroyed the two German corps and most of their constituent divisions.

In a scene typical of Operation Cobra, a US infantry company moves up along a hedge-lined country road on 27 July. The wartime censor has obliterated the unit insignia on the riflemen and jeep making it impossible to determine the precise unit.

The key road junction at Coutances fell on 28 July to CCB, 4th Armored Division, which had advanced down the coast against modest opposition. Here a heavily camouflaged M5A1 light tank passes through the damaged town.

The faces of these German prisoners in Coutances on 29 July reveal a mixture of exhaustion and relief at having survived the intense fighting of the previous weeks in the bocage.

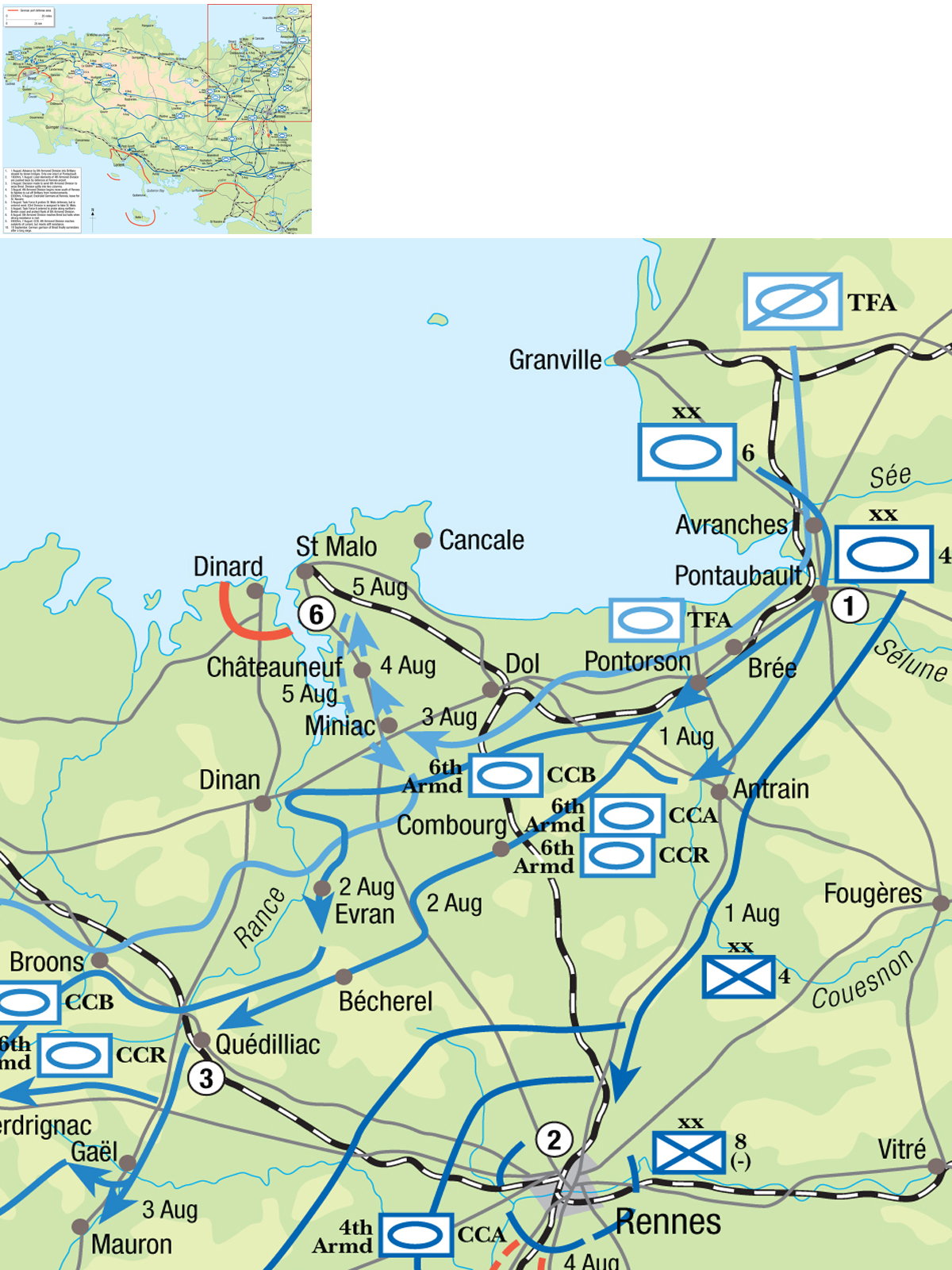

The original American plan called for a period of consolidation after the breakthrough. Given the success of Cobra and the disarray in the German forces, exploitation rather than consolidation was the obvious alternative. The Germans had not given any thought to defenses in depth, and US armored spearheads captured most bridges before they could be prepared for demolition. Bradley’s staff began laying out plans on the evening of 27 July. By 29 July both 4th and 6th Armored Division were advancing with minimal opposition. Although strung out, their main problems were mines and large numbers of surrendering Germans, not determined resistance. The VIII Corps commander was particularly impressed by the performance of 4th Armored Div., led by the aggressive MajGen John Wood. Late on 29 July he gave Wood the assignment of taking Avranches. The following day lead elements of the 4th Armored Division came close to capturing Hausser and the Seventh Army staff during a lightning advance. Early in the evening the tanks entered Avranches. The situation in the town remained confused, and a major action took place on the night of 30 July when Germans troops retreating from further north attempted to break through the thinly held American positions. The next critical mission was to seize the main bridge over the Selun river at Pontaubault which led from the Cotentin region into Brittany. German defenses in the region were in such disarray that a 4th Armored Division task force seized it on the afternoon of 31 July without resistance, followed by capture of secondary bridges in the area. On 31 July alone, the 4th and 6th Armored Division captured 4,000 prisoners and the infantry following behind bagged another 3,000. On 31 July Kluge contacted the OB West by telephone, describing the situation as a “Riesensauerei” – a complete mess. Kluge blamed Hausser for his ill-advised decision to break out to the south-east. When asked by chief-of-staff Blumentritt what defenses were in place, he sarcastically suggested that the high command must be “living on the moon”. He warned that “if the Americans get through at Avranches they will be out of the woods and they’ll be able to do what they want … The terrible thing is that there is not much that anyone could do … It’s a crazy situation.” Kluge attempted to get troops from the St. Malo garrison to seize the Pontaubault bridge, but by the time a Kampfgruppe from the 77th Division arrived, it was already firmly in American hands. In desperation the Luftwaffe was ordered to attack the bridges. Due to Allied air superiority the attacks had to be conducted at night. Dornier Do-217s of KG 100 began attacks on the night of 2 August using Hs 293 guided missiles. Attacks through 6 August were ineffective and six aircraft were lost.

Coutances remained a key road junction for US forces moving into Brittany to the south-west. Here an M4 (105mm) assault tank moves past a disabled auto that had been commandeered by German troops. The M4 (105mm) tank was armed with a 105mm howitzer instead of the usual 75mm gun and was deployed in each tank battalion headquarters company to provide indirect fire support for the unit.

This PzKpfw IV was knocked out by a 37mm gun mounted on a M2 half-track of the 41st Armored Infantry Regt. of the 2nd Armored Div. during fighting for St. Denis-le-Gast on 31 July. A tanker from the supporting 67th Armored Regt. points to a hole in the turret side skirts where the 37mm round penetrated. This tank was most probably from 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich”.

Kluge attempted to prevent Cobra from spilling over the Vire river by sending the 2nd Panzer Division to Tessy-sur-Vire in late July. The town was finally taken by the CCA/2nd Armored Division and the 22nd Infantry on 1 August. The destroyed German armor left behind included this Flakpanzer 38(t) of Pz.Rgt. 3. This was the most common type of German anti-aircraft vehicle in Normandy and consisted of a 2cm automatic cannon mounted on a Czech PzKpfw 38(t) tank chassis.

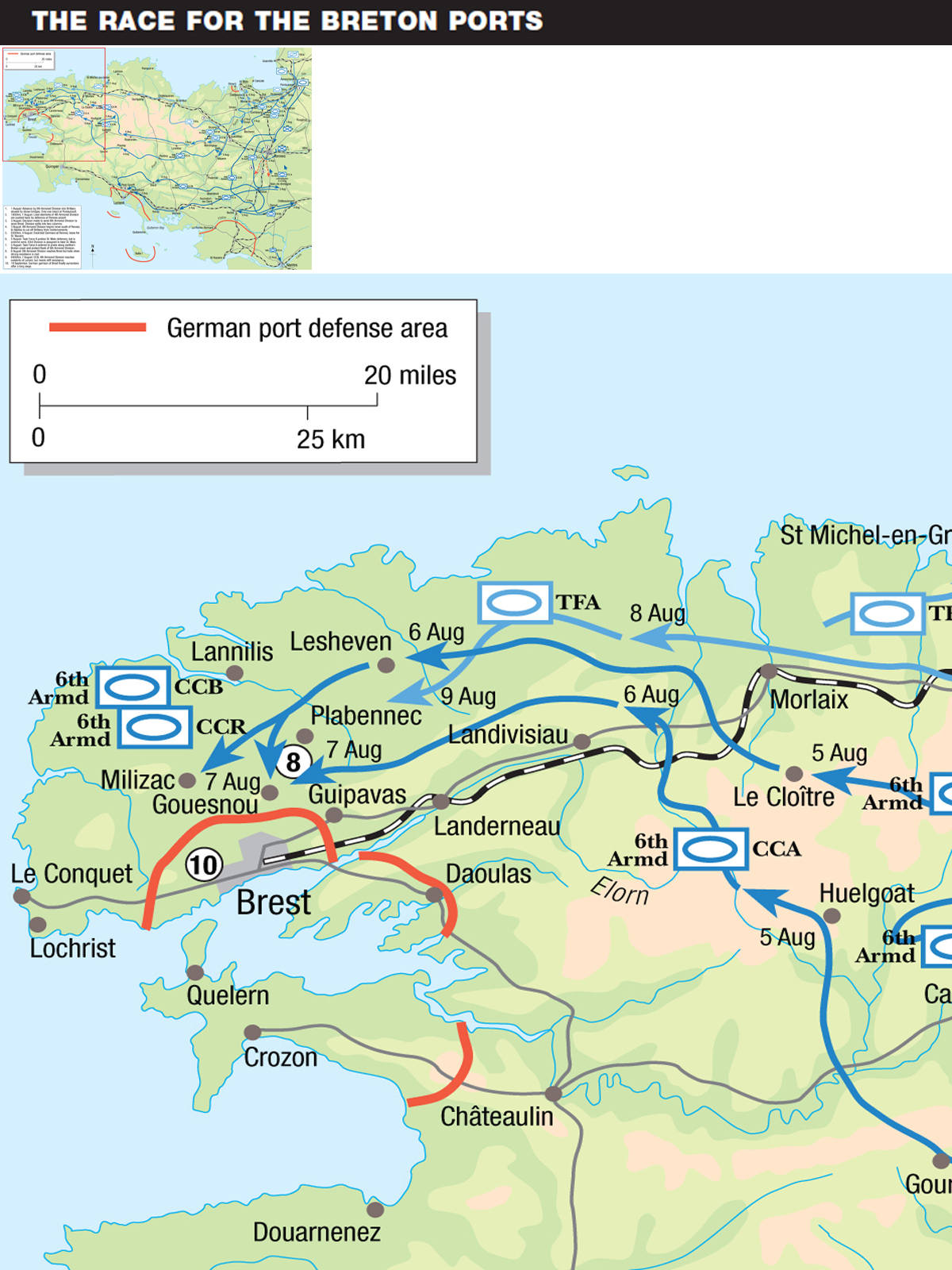

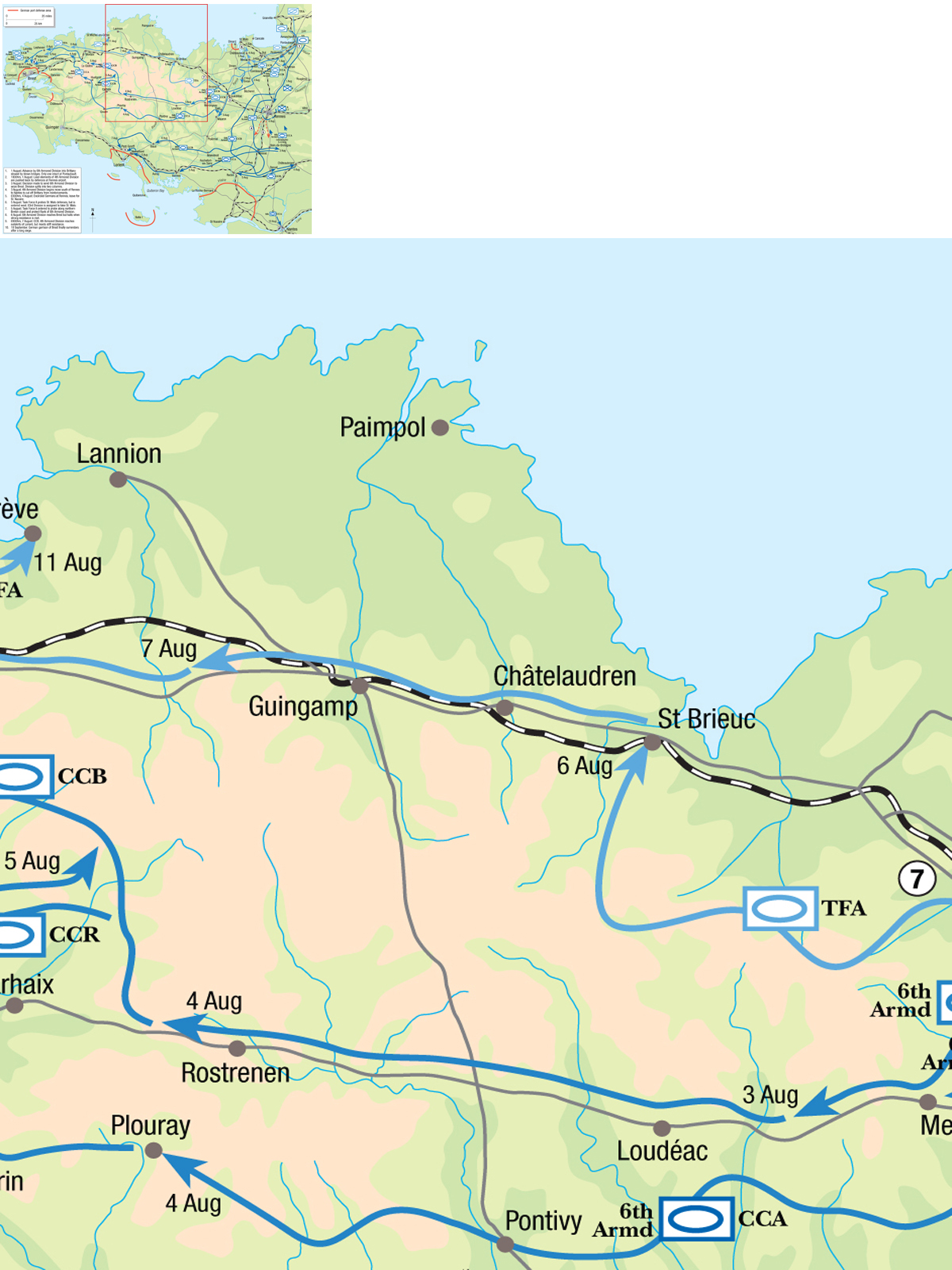

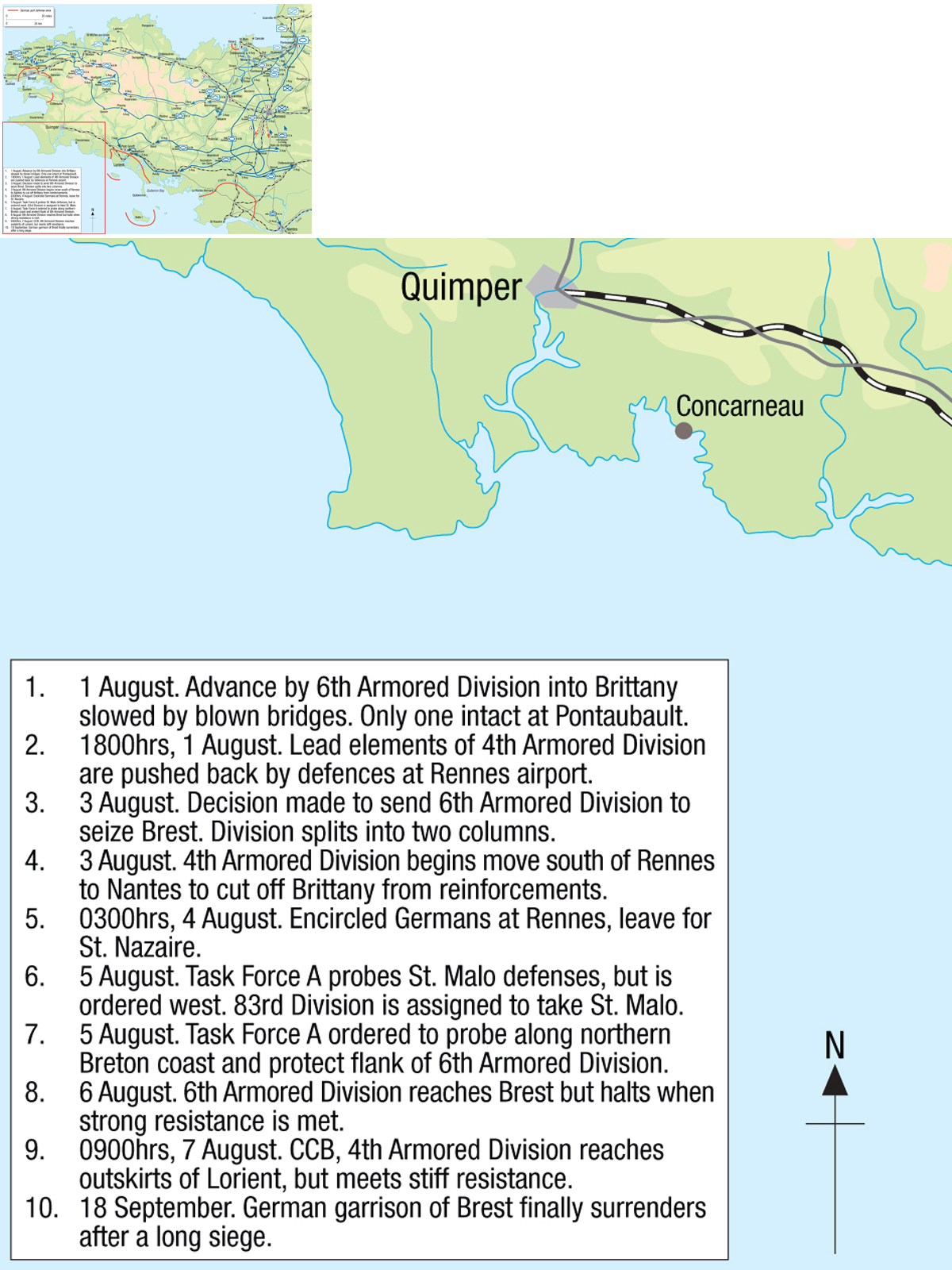

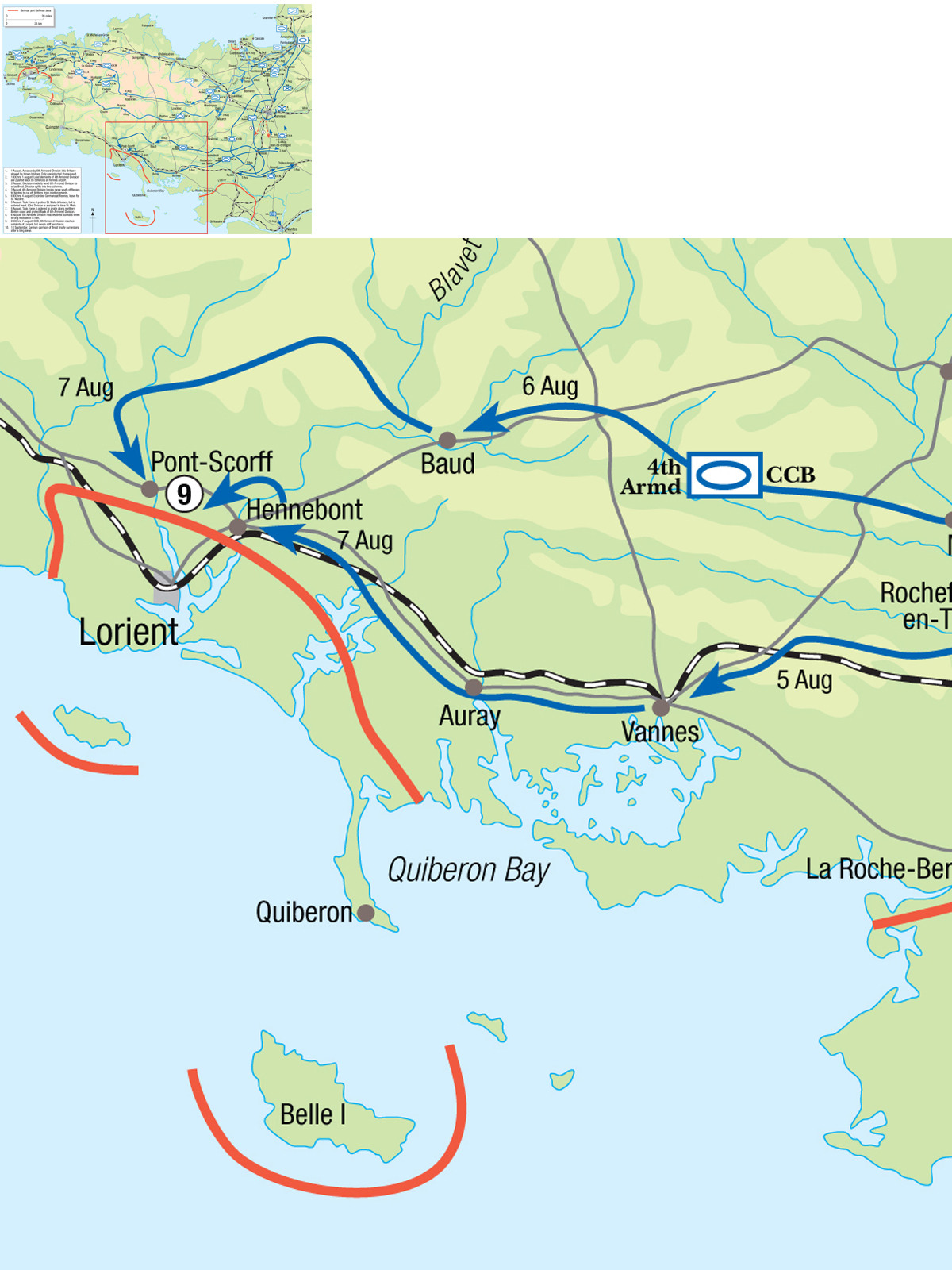

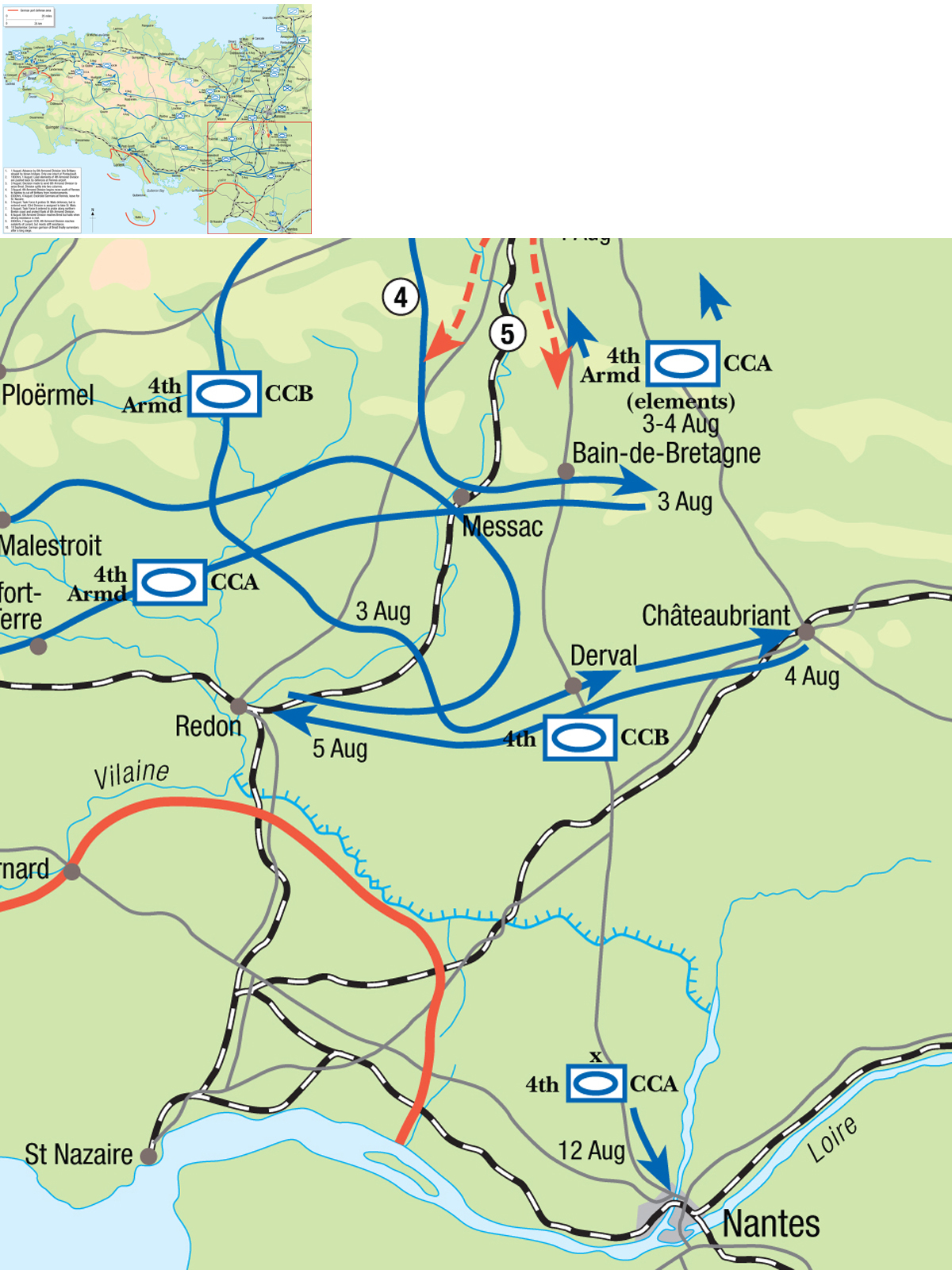

On 1 August, as previously planned, the First US Army was transformed into the 12th Army Group. Patton’s Third Army was activated, taking over the divisions operating on the approaches to Brittany. The 4th Armored Division’s race towards the Breton capital of Rennes was stopped on 1 August by a determined defense of Rennes airport, stiffened by Luftwaffe 88mm anti-aircraft guns. Further German reinforcements arrived, and even after air strikes, the defense withstood another 4th Armored Division attack. The 6th Armored Division was on the heels of the 4th Armored Division into Brittany, delayed by the constricted access at the Pontaubault bridge.

While awaiting infantry reinforcements to take Rennes, Gen Wood considered how best to deploy his division. He became increasingly convinced that Brittany could be taken by infantry and that the real armored mission would be eastward, not westward. To carry this out it would be necessary to seal off Brittany from the rest of France by attacking south. Once accomplished, this would place the 4th Armored in a position to move eastward again. Middleton, the VIII Corps commander, did not immediately agree and reiterated the need to seize Rennes. Armored divisions were not well suited to city fighting so Wood sent his columns to surround the city and cut off reinforcements. On the night of 3 August Hausser gave the commander of the Rennes garrison, by now almost surrounded, permission to abandon the city, and about 2,000 German troops infiltrated past the thinly held American lines. CCA of the 4th Armored Division reached Vannes on Quiberon Bay on 5 August, effectively sealing off Brittany. The Germans responded with a counterattack from the west near Auray, but were beaten back. In the meantime CCB of 4th Armored Division moved on the port city of Lorient, reaching the outskirts of the city on the morning of 7 August. After two days of probing the defense it became apparent that the city could not be taken by an armored division. The city was well defended on the landward side by anti-tank ditches and minefields, and the port’s substantial anti-aircraft defenses were reinforced with coastal guns, anti-tank guns, and naval cannon, estimated to total about 500 guns. In fact the defenses of Lorient were weaker than the Americans assumed, with 197 artillery, 80 anti-tank guns, and a garrison of 25,000 troops. The garrison commander later stated that he believed that the US Army could have seized Lorient in early August due to the disorder in the port. However, the 4th Armored Division was weak in infantry and US doctrine did not favor the use of armor in fortified urban areas. With Lorient surrounded Wood sent Patton a message: “Dear George: Have Vannes, will have Lorient this evening … Trust we can turn around and get headed in the right direction soon.” Wood would later get his wish, as Patton was itching to move eastward as well.

Through late July and early August, the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions attempted to halt the advance of the US 2nd Armored Division along the Vire river, leading to some of the most intense tank fighting of Operation Cobra. The key road junction of Pontfarcy finally fell on 3 August 1944, and here US infantry walk past a knocked-out PzKpfw IV tank, probably from 116th Panzer Division.

Although the US Army was assigned the task of seizing the Breton ports in the original Overlord plans, the German success in demolishing Cherbourg harbor prior to its capture suggested the same might happen in Brittany. Army logisticians suggested an alternative – the construction of a new harbor in Quiberon Bay. While the 4th Armored Division sealed off Brittany, the 6th Armored Division penetrated deeply westward. On 3 August Middleton decided that 6th Armored Division should seize the main port at Brest as quickly as possible. The division’s right flank would be covered by Task Force A moving along the northern Breton coast, which would also be responsible for isolating the garrison at the port of St. Malo. Task Force A was an improvised force including the 6th Tank Destroyer Group, 15th Cavalry Group and 159th Engineer Battalion, created by Patton to seize the key bridges into Brittany. Patton had no intention of laying siege to port cities like St. Malo, so he ordered Task Force A to bypass the city once it became clear that the Germans intended to defend it.

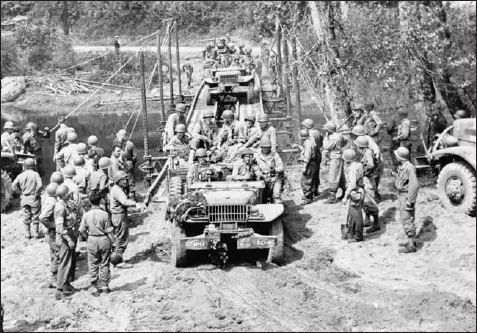

The Vire river had been the eastern boundary of the US advance during Operation Cobra since the main emphasis was a swing westward to trap the Seventh Army. With the encirclement completed attention shifted eastward. This is the first motorized column over the Vire on 3 August after engineers have erected a treadway bridge for the 35th Division.

At the head of the retreating column from 2nd SS Panzer Division at the crossroads near Notre-Dame-de-Cenilly was this 150mm Hummel self-propelled gun named “Clausewitz” and SdKfz 251 half-track, followed by about 90 other vehicles and 2,500 Waffen-SS troops. It was finally stopped around midnight at a roadblock of Co. I, 41st Armored Inf. Regt., 2nd Armored Div. when the driver and gunner were shot at close range. The ensuing traffic jam along the hedgerow-lined road left the remainder of the retreating column exposed to American fire, and a savage nighttime battle began in which the column was largely destroyed.

The 83rd Division was brought into Brittany to deal with St. Malo, but an initial attack against the fortified port on 5 August made it clear that a more determined assault would be needed. Reinforced by a regiment from the 8th Division as well as tank and air support, the battle for the surrounding forts and blockhouses began in earnest on 7 August. By 9 August the attack had driven the Germans back into Dinard on the west bank of the Rance river, and nearly to the walls of the old town. Concentrating on Dinard on 11 August, the town was finally captured on 14 August after intense house-to-house fighting. The fighting for St. Malo itself was complicated by the presence of a number of forts along the coast, including the fortified Cézembre island. At the heart of the defenses was the Citadel, a mid-eighteenth century fortress complex that had been reinforced by the Germans. Attacks by two groups of medium bombers with 1,000lb bombs failed to dent it. After repeated assaults and direct fire by 8in. guns from only 1,500 yards, the Citadel finally surrendered on 17 August. The offshore Cézembre fortifications were pummeled by bombers and naval gunfire and weren’t finally secured until 2 September. The port itself was a shambles, and the difficult fighting around St. Malo convinced many senior American commanders that the other fortified coastal ports would not be worth the effort.

Some idea of the carnage on the road back from the roadblock can be seen in this photo taken outside St. Denis-le-Cast the next day. The abandoned hulks of a number of SdKfz 251 halftracks have already been pushed off the road. The second half-track in the column is an SdKfz 251/7 bridging vehicle from an engineer company of Das Reich. Behind it is a burned-out M4 medium tank of the 67th Armored Regt. destroyed during the nighttime battle.

While the siege of St. Malo was taking place, the 6th Armored Division raced through central Brittany against minimal German defenses. The American drive was further assisted by the French resistance, the FFI (French Forces of the Interior), which was extremely active in the region. Nevertheless, the thrust by a single armored division 200 miles into enemy-held territory was risky. Cavalry scouts finally reached the outskirts of Brest late on 6 August. As 6th Armored Division moved through central Brittany, Task Force A continued its drive along the northern coast, taking many small German garrisons by surprise. It finally joined up with the 6th Armored Division in the outskirts of Brest on 7 August. There were no plans to make a direct assault on Brest, as the corps felt that a single armored division would have all the impact of “a bug against the shell of a turtle”. Brest was a heavily fortified city and it was assumed a siege would be needed. It was garrisoned by the 343rd Division, some assorted Wehrmacht units, improvised naval infantry and two coastal batteries totaling about 15,000 troops. The garrison was reinforced on 9 August when the 2nd Parachute Division slipped into Brest from the south after being redirected from a planned move into Normandy, and by mid-August the garrison strength rose to 35,000.

The 6th Armored Division commander, MajGen Robert Grow, hoped that the Germans might only plan a token defense. So on 8 August a jeep under a white flag carried a surrender ultimatum to the Brest garrison which was promptly rebuffed. A planned attack on the city defenses was halted later in the day due to increasing fighting along the division’s outposts. The German 266th Division had withdrawn from eastern Brittany and was attempting to fight its way into the Brest garrison. For the next day, the 6th Armored Division was engaged in a series of skirmishes with the German infantry. Grow still hoped that a determined assault could break into the city, but attacks on 11 and 12 August near Guipavas failed. It was apparent that heavy artillery and additional air support would be needed. This was unlikely, as the corps’ heavy artillery was already committed to the assault on St. Malo. On 12 August Grow was told to leave one of his combat commands to block off the city and divert the other two back towards Vannes to relieve the 4th Armored Division. Patton was finally shifting his attention eastward.

The tail end of the retreating German forces were caught in the town of Roncey where much of their equipment was left abandoned after a series of intense air strikes. Here a woman from the town walks past several wrecked Panzerjäger 38(t) Marder III of SS-Panzerjäger Abteilung 17.

The Brittany operation had been remarkable for its speed. The 6th Armored Division’s drive on Brest was the most extended operation ever conducted by a single US division in Europe in 1944–45. Yet the strategic goal of seizing the Breton ports had not been accomplished since the armored units were not strong enough to force their way into the fortified ports. Brest did not fall until 19 September and its harbor was completely demolished; plans to assault Lorient and St. Nazaire were cancelled and the isolated garrisons did not surrender until the end of the war. While the Breton ports had seemed valuable in July, by August more alluring opportunities had presented themselves. A deep encirclement of German forces along the Seine river now seemed a real possibility, which might put closer ports such as Le Havre and Antwerp in Allied hands.

By the beginning of August, Hitler finally appreciated that the Normandy front now posed the most serious threat to Germany. After nearly two months of catastrophe in the east, the Red Army’s drive into central Europe had stalled on the Vistula river in central Poland. The Red Army continued to advance into the Balkans, but this directed the drive away from Germany. The German armed forces in France had two options – to attempt to confine the Allies in Normandy, or to allow Army Group B to withdraw to the Seine river. For a variety of both political and military reasons, Hitler decided that a continued defense of Normandy was the more prudent option. The Normandy front was shorter, and the Seine by no means presented an insurmountable obstacle to the Allies. Six divisions were in the process of being transferred to Normandy, one panzer and five infantry divisions.

An M3A1 half-track of the 2nd Armored Division passes by some of the wreckage in Roncey on 1 August. This is a view from the other end of the church and an armored SdKfz 7 halftrack fitted with a quadruple 2cm anti-aircraft cannon can be seen near the wreck of a Marder III of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division.

Some idea of the intensity of the bombardment during Operation Cobra can be gathered from this aerial photo. During the retreat of the 2nd SS Panzer Division, a German column was caught in the open during daylight and hit by medium bombers. This view was taken days later after the road had been cleared for use by US troops.

The sudden advance of the US 4th and 6th Armored Divisions down along the coastal roads near Avranches caught many retreating German columns by surprise. This road outside of Avranches on 1 August presents a typical picture of devastation, repeated many times in the Cotentin area in late July and early August.

The most immediate problem was how to plug the gap from Vire to Avranches caused by Operation Cobra. In a predictable fashion, Hitler decided on a violent panzer counterattack. Hitler’s original plan was to disengage the 2nd SS Panzer Corps and deploy it against the Americans. But due to continuing British pressure, this was ruled out. Instead, Hitler decided to use the 47th Panzer Corps consisting of the 2nd and 116th Panzer Divisions already along the Vire, supplemented by survivors of the 2nd SS Panzer Division and the recently arrived 9th Panzer Division. In addition, Kluge received permission to draw the 1st SS Panzer or 12th SS Panzer Division from the British sector to serve as an exploitation force, as the Caen sector had become somewhat quieter. This counteroffensive, codenamed Operation Lüttich (Liege), would emanate from the area around Mortain. It would strike across the base of the American advance to Avranches on the coast, a distance of about 20 miles, thereby cutting off all the forward American divisions. The attack was planned for 6 August.

To support this operation the American advance eastward had to be slowed or halted all together. Hausser’s Seventh Army began to receive reinforcements to establish a coherent defensive line along the Vire river against Hodges’ First Army. The aim of this force was not only to hold back the US drive, but also to free up the panzer divisions now holding the front, so that they could prepare for the intended armored counterattack. During the first week of August the German front line was pushed over the Vire river to the south-east, finally coming to rest along a line from Mt. Pinçon in the north, through Vire, to the outskirts of Mortain in the south. The First Army captured both Vire and Mortain, but the German defenses around Sourdeval proved too difficult to reduce.

The capture of Avranches left many German units surrounded along the coast. A familiar sight was large numbers of prisoners of war like these being marched down a nearby country road on 2 August 1944.

From the American perspective, the original intentions for Operation Cobra had already been fulfilled, especially in view of the progress of Middleton’s VIII Corps in Brittany. Furthermore, the weakness of the German forces in Brittany allowed the operation to be conducted with a single corps instead of requiring two or more as had been planned. Bradley’s options were further enhanced by the arrival of yet another corps in Patton’s Third Army – XV Corps under MajGen Wade Haislip in early August. Rather than deploy it in Brittany, Bradley decided that the opportunity now existed for the 12th Army Group to plunge eastward towards Le Mans and, eventually, the Seine river. The spearhead for the new corps was the fresh 5th Armored Division. The corps began moving on Le Mans with the 5th Armored forming the right, southern flank, with the 79th and 90th Divisions to the north.

With the German left flank so weak, and the right flank around Caen still stiffly defended, senior Allied leaders began a series of discussions to alter the original Overlord plans. The aim shifted to the destruction of the German army west of the Orne river. These plans became more formal on 3 August when Bradley instructed Patton to clear Brittany with a minimum of forces. Montgomery strongly backed this venture, recognizing that it represented a shift in Allied strategic thinking that could lead to the Allied right flank sweeping eastward all the way to Paris. The shift was intended to direct Patton’s Third Army along the axis of Laval–Le Mans–Chartres. Initial planning began for an airborne landing near Chartres to keep open the Paris–Orléans gap, an action which later proved unnecessary.

The cavalry served a vital role in the exploitation phase of Cobra racing through gaps into the German rear areas. Here an M8 armored car of the 42nd Cavalry Recon Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Group receives a warm welcome in Brehal on the northern approaches to Avranches on 2 August 1944.

The immediate tactical issue became whether to direct Haislip’s XV Corps south-east, or directly east. Patton was ordered to secure a 60-mile stretch along the Mayenne river from Mayenne to Château-Gontier using the Loire river to protect his right flank. A third corps was added to Patton’s Third Army to help accomplish this, with the new XX Corps being assigned to secure the right flank. Patton warned Haislip that he might expect orders to move north or north-east if opportunities presented themselves, and the rule of the day was “Don’t stop”. Pockets of resistance were to be bypassed, and the French FFI was given the assignment of harassing and tying down isolated German garrisons. Patton hoped to use the XIXth Tactical Air Command to serve as aerial cavalry, keeping an eye on his flanks for any unexpected German counter-actions. The cities of Mayenne and Laval fell with minimal resistance, and it became obvious that German forces in the area were disorganized. On 5 August Patton was given permission to take Le Mans.

Kluge was unwilling to let Le Mans fall as easily as Laval, since the area contained rear elements of the Seventh Army and critical supply and fuel dumps. The 708th Division and lead elements of the fresh 9th Panzer Division were moved to defensive positions along the Mayenne river. The spearhead of the 90th Division ran into the German forces near Aron on 6 August. The 90th Division had come out of Normandy with a bad reputation and was widely regarded as the worst US division in France. To rectify its problems Bradley had replaced the divisional commander, and it was now headed by a first-rate officer, MajGen Raymond McLain. Leading the 90th Division assault was an aggressive commander, BrigGen William Weaver. When confronted by strong German defenses, Weaver exploited the speed of attached elements of the 106th Cavalry Group to look for new avenues of approach. In two days of fighting Weaver’s task force had pushed to the outskirts of Le Mans, decimating the reconnaissance battalion of the 9th Panzer Division and a regiment of the 708th Division, and taking 1,200 prisoners. The 79th Division accelerated its own drive by motorizing one of its regiments, and Le Mans was entered by US troops in the afternoon of 8 August. To the south of the infantry divisions, the 5th Armored Division had advanced with little opposition, moving so quickly that its main problem was a growing lack of fuel. By 8 August the 5th Armored Division was on the eastern side of Le Mans cutting off the retreat of any remaining German troops.

THE PANZER COUNTERATTACK AT MORTAIN, 7 AUGUST 1944

Allied air cover made it very difficult for the Germans to mass armor for the counterattack towards Avranches. The 1st SS Panzer Division made the move late on 6 August, with some of the tanks of SS Panzer Regiment 1 not arriving until after dawn, as seen here. Camouflage was essential in Normandy for defense against air attack, and most German tanks were carefully covered with foliage and tree branches prior to any movement. This often became dislodged during the transit, and would sometimes be thinned out prior to an attack to prevent branches from covering up telescopic gun sights and vital periscopes. SS Panzer Regiment 1 was equipped with a variety of types, including some of the early Ausf. G version of the Panther tank as seen here. These were still coated with zimmerit anti-magnetic paste, a useless feature in France as the Allies did not use magnetic anti-tank grenades. (Tony Bryan)

The advance of Haislip’s XV Corps clarified the strategic picture. It was becoming obvious that the German forces lacked the strength to contest the Third Army’s advance. Patton wanted to continue to push eastward towards the Paris–Orléans gap. Montgomery, likewise, saw the strategic opportunity and began steps to launch offensive operations towards Falaise in the south using the fresh First Canadian Army. Montgomery felt that the Germans had no alternative but to withdraw to the Seine, and should they begin to do so his forces had to be ready to pursue them, to turn an orderly withdrawal into a rout. Bradley expected that the Germans would react in their usual fashion and launch a counterattack, probably from the Domfront area.

Preparations for Operation Lüttich were delayed a day, from 6 August to 7 August, due to logistical problems. Expectations for the counteroffensive were starkly different in France than at Hitler’s headquarters. Hitler’s exaggerated expectations were evident in his order: “The decision in the battle of France depends on the success of the (Avranches) attack. The OB West has a unique opportunity which will never repeat to drive into an extremely exposed enemy area and thereby to change the situation completely.” Kluge held more realistic expectations that the operation might provide some breathing space for an orderly retreat behind the Seine river. During a phone conversation with Kluge on 6 August, Hitler promised to release 60 Panther tanks held in reserve in the Paris area, as well as 80 PzKpfw IV tanks from the 11th Panzer Div. in southern France. While welcome, these would not be available for the initial effort, and were a pitiful reminder of the poverty of German reserves in France.

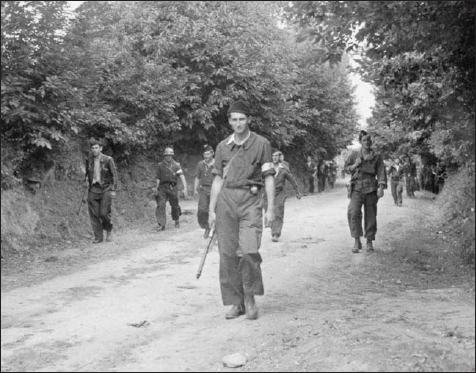

The FFI French resistance movement provided invaluable aid in the Brittany campaign isolating German garrisons and providing intelligence. This is an FFI unit assisting the US Army in patrolling the outskirts of the port of Lorient in August 1944.

It quickly became clear that the German garrison in the old fortified port of St. Malo would not give up easily. This led to the first protracted siege in Brittany. Here GIs from the 331st Infantry are engaged in street fighting in the town on 8 August.

While Bradley and Hodges both anticipated a counterattack in the Domfront–Mortain area, they had little advance warning on the time or size of the assault. On 6 August Allied tactical aircraft noted a build-up of German armor to the northeast of Mortain. In addition, the Allied codebreakers had intercepted a Luftwaffe message regarding the support of Operation Lüttich which indicated that five panzer divisions were to strike from Sourdeval and Mortain with an initial objective of the Brecey–Montigny road. The Ultra decrypt formed the basis for an alert at 1700 on 6 August.

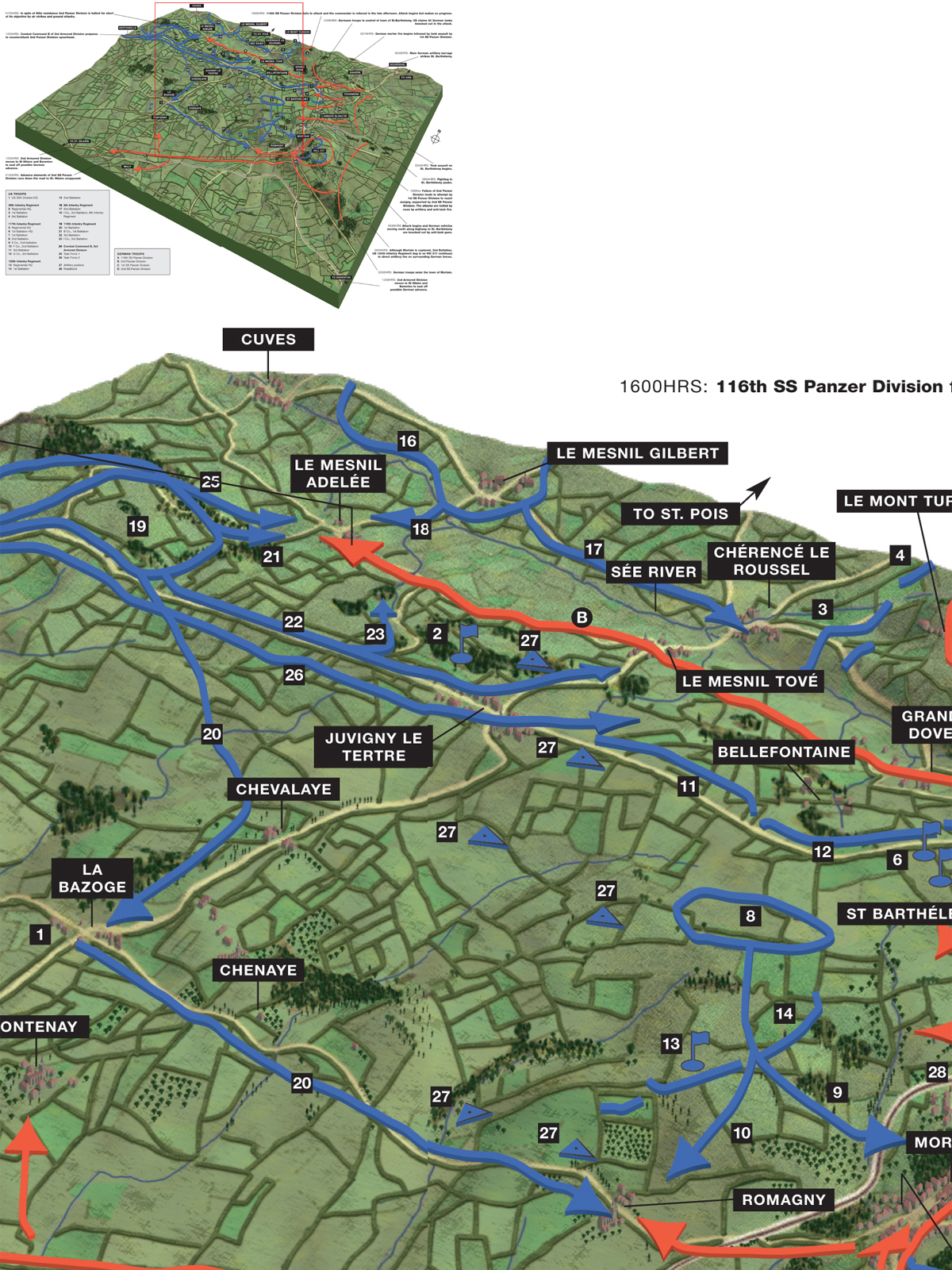

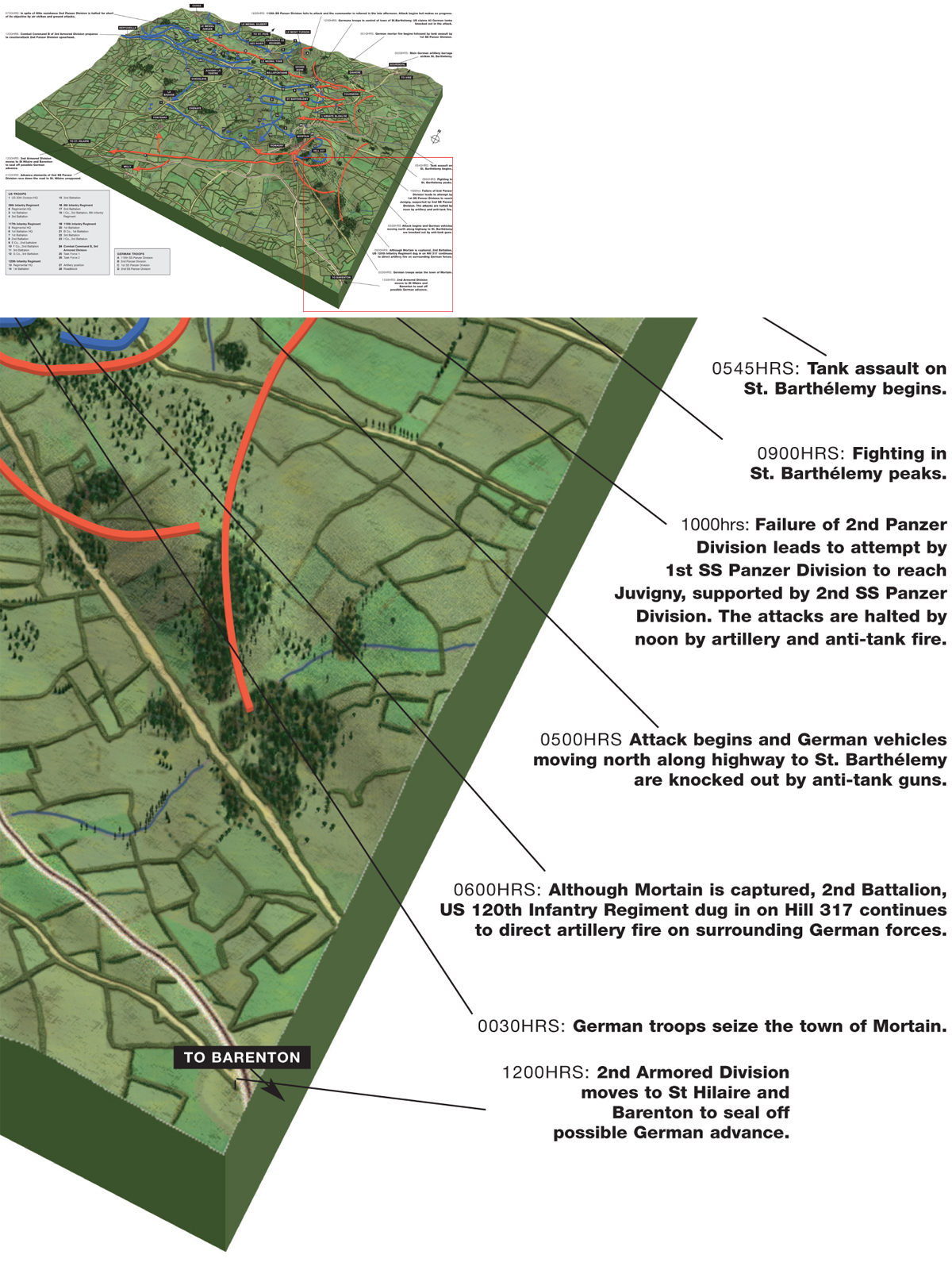

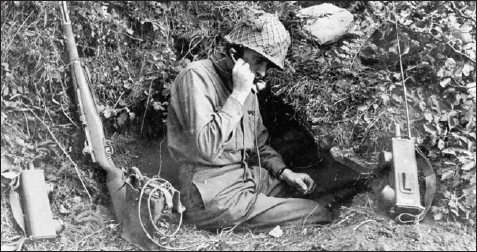

Mortain and the surrounding area had been occupied late on 6 August by the US 30th Division. Around midnight of 6/7 August the division received a warning from VII Corps HQ that the Germans might counterattack near Mortain the following day and they were to assume a defensive posture. The warning came too late for much action. The division had already deployed two of its regiments, the 117th Infantry in and around St. Barthelemy and the 120th Infantry in Mortain itself.

German preparations for the attack were far from complete. Around 22.00hrs on 6 August the 47th Panzer Corps commander, Gen Hans von Funck, telephoned Hausser requesting a postponement of the attack. The 1st SS Panzer Division had been late in arriving and would not reach its start point on time. Funck also demanded that Hausser relieve the commander of the 116th Panzer Division, GenLt Gerhard Graf von Schwerin, who had failed to dispatch a tank battalion to the 2nd Panzer Division. Knowing of Hitler’s great expectations for the attack, Hausser refused to postpone the attack, but delayed the start two hours until midnight. A total of about 120 panzers were available for the attack as well as 32 assault guns and tank destroyers.

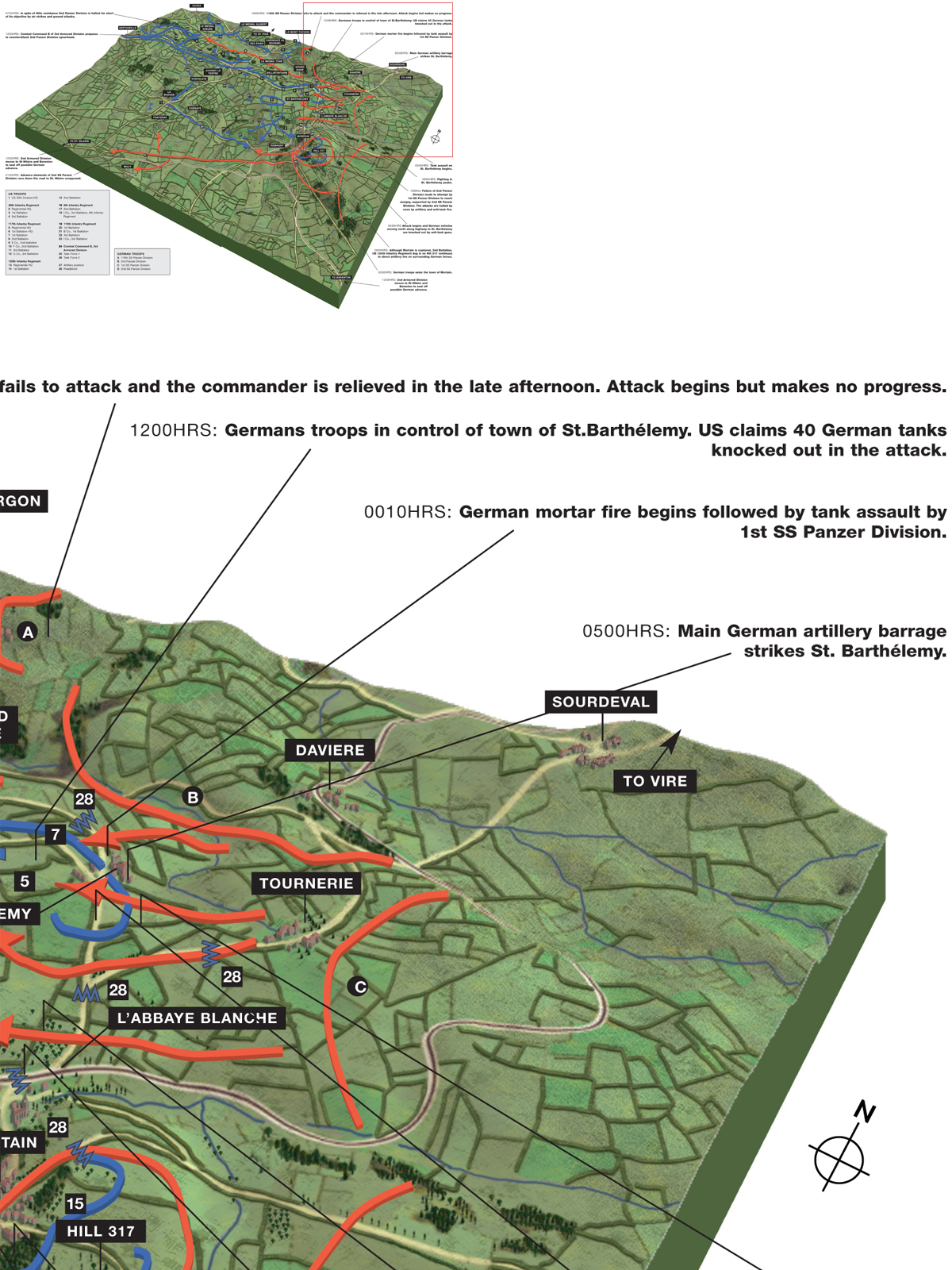

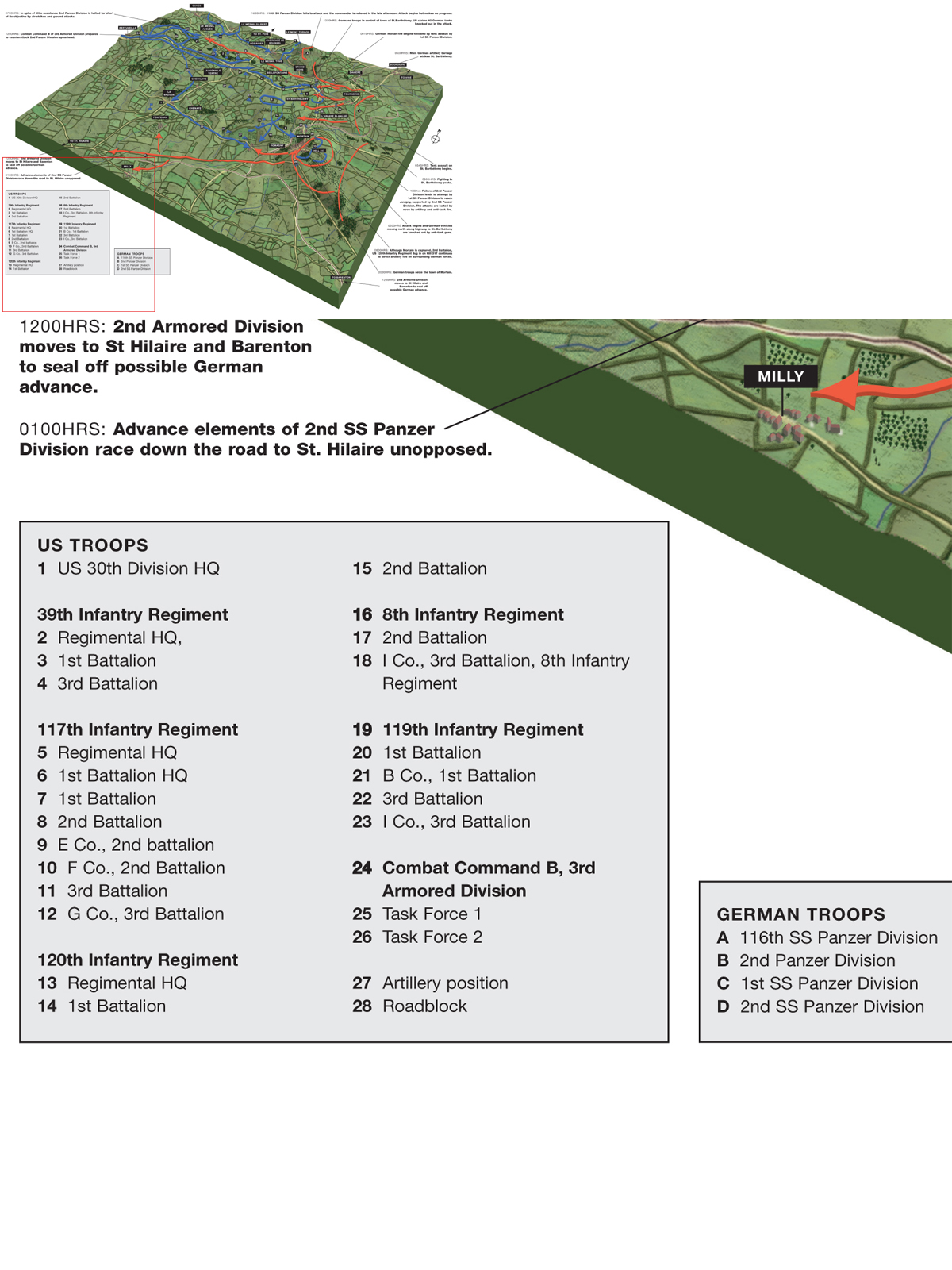

Operation Lüttich began shortly after midnight without a preliminary artillery bombardment. As was common in the area a dense fog had settled in, much to the relief of the Germans, who hoped it would provide a shield the next morning from Allied air attack. In the southern sector the 2nd SS Panzer Division pushed into the town of Mortain before dawn, largely unopposed, and sent a column down the road to St. Hilaire with no evident opposition. However, the value of Mortain was severely undermined by the fact that the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry was still entrenched on Hill 317 on the eastern edge of the town behind German lines, giving it vistas over the town and the neighboring roads. In addition, other infantry companies with anti-tank guns occupied positions to the west of the town.

7 August 1944, viewed from the south east, showing the attacks by 1st SS, 2nd SS and 2nd Panzer Division and the US response.

The commander of St. Malo, Andreas von Auloch, a veteran of Stalingrad, was dubbed the “Mad Colonel” by American troops for his determined resistance to the US siege. His die-hard defense of the fortified Citadel finally collapsed on 17 August when the US Army brought 8in. guns to within 1,500 yards to fire directly into embrasures and vents. Here he is seen being escorted to the surrender by officers of the 83rd Division.

The main thrust by the 2nd Panzer Division drove far deeper west, almost six miles, encountering few American troops. Shortly after daybreak, it was halted by a task force of the 119th Infantry in the town of Le Mesnil-Adelée. The left column of the 2nd Panzer Division waited until dawn to attack when the panzer battalion from 1st SS Panzer Division finally arrived. PzKpfw IV tanks of Panzer Regt. 3 supported by tank destroyers of Panzerjäger Regt. 38 attacked the northern side of St. Barthelemy while Panthers and PzKpfw IV tanks of SS Panzer Regt. 1 struck the southern side. They encountered 57mm anti-tank guns and bazooka teams of the 117th Infantry, as well as a two platoons of towed 3in. anti-tank guns of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion. This attack finally overcame the infantry battalion in the town late in the morning, but any further advance proved impossible.

Immediately prior to Auloch’s surrender the 8th Air Force had planned another major bombing mission against the St. Malo defenses. Following the surrender the bombers, like this B-24 of the 389th Bomb Group, 2nd Bomb Wing, were redirected to attack German positions on Ile de Cézembre off St. Malo. The fortified island did not surrender until 2 September after days of aerial and naval bombardment. (Patton Museum)

As German defenses in Brest stiffened the surrounding US forces brought in more artillery to lay siege to the port. This is an M3 105mm howitzer of the 9th Cannon Company, 2nd Division nicknamed “Hitler’s Doom” preparing to fire on 28 August 1944. This lightweight howitzer was used in place of the heavier and more common M1 105mm howitzer in some infantry divisions in Normandy. Its maximum range of only 8,300 yards and lightweight construction limited its wider use.

The northernmost element of the attack, the 116th Panzer Division, failed to launch its attack. The 84th Division was supposed to relieve the panzers for the attack, but Schwerin doubted that it could withstand the American pressure. Schwerin withheld the orders for the attack from his subordinates. As a result of Schwerin’s insubordination and the other problems, only three of the six panzer columns launched the attack on time, and the fourth column set off five hours late. Promised air support from Jagdkorps 2 was even less impressive, amounting to only a single night raid by medium bombers around 02.00 that mainly hit open fields near St. Barthelemy.

The initial American impression of the attack was not alarming. VII Corps reported to the First Army that “the attacks appeared to be uncoordinated units attempting to escape rather than aggressive action.” However, as further radio reports were made by the forward infantry battalions around daybreak it became evident that a serious attack was under way. At dawn, Hodges and Collins conferred over necessary actions. The most alarming element of the German attack was the 2nd SS Panzer Division detachment on the St. Hilaire road. The Americans were not aware how weak this probe really was, but they were concerned since it was advancing towards a gap in American lines. Collins ordered CCB of the 3rd Armored Division, immediately behind the 30th Division, to deal with this threat. This area was reinforced later in the day by elements of the 2nd Armored Division which also reinforced Barenton. Additional divisions were brought forward from reserve or reassigned, so that by late on 7 August VII Corps had five infantry and two armored divisions in the immediate vicinity of Mortain to react if needed.

The defense of Brest finally collapsed at the end of August. Here a GI from the 23rd Infantry, 2nd Division keeps an eye on a Wehrmacht medic as he exits a bunker following the surrender.

After sunrise the ground fog began to dissipate. The strung-out German columns, encountering stronger resistance than expected, began to take up defensive positions in anticipation of Allied air strikes. Since the US infantry still held hills overlooking German positions, divisional artillery began to rain down. The first flight of P-47s took off for Mortain at 08.30, and by late morning Allied aircraft swarmed the area, including rocket-firing British Typhoons. The Luftwaffe promised 300 fighters from airfields near Paris, but scores of aircraft were lost in dog-fights near their airfields and no German fighters patrolled over Mortain. The blue skies gave the GIs of the 30th Division a clear vista of German positions from their hill top positions, and they were able to call down accurate artillery fire all day long. The German units did not advance much further than the positions they had reached by morning, and indeed they would not proceed any further through the course of the fighting. While the panzer divisions had developed excellent defensive tactics in their fighting in the British sector in the previous month, they were plagued by the same sorts of problems as the US Army when attempting to conduct offensive operations in the bocage. The terrain favored the defender and the constricted road network and hedges made the panzers vulnerable to flank shots from 57mm anti-tank guns and bazookas. German tank casualties to American anti-tank guns and bazookas were heavy. The US infantry estimated they had knocked out about 40 panzers during the course of the day’s fighting, a third of those committed.

The defense of Brest was aided by the presence of a number of coastal artillery batteries which provided heavy fire support. The most famous of these was the Graf Spee battery located on the south-west tip of Brittany to the east of Brest near St. Mathieu. This consisted of four 280mm naval guns that were operated by Marineartillerieabteilung 262. The battery was pummeled by air attack and even by fire from the battleship HMS Warspite. It finally fell to a ground assault on 9 September after Brest itself had been captured. This is one of three partially protected guns; the fourth was enclosed in a coastal bunker.

Each US infantry battalion had three 57mm anti-tank guns, which proved vital to stopping Operation Lüttich. Although not capable of defeating the Panther tank from the front, they could penetrate its weaker side armor. This gun is from the 12th Infantry, 4th Division, which covered the shoulder of the German attack on Mortain.

Air attacks severely limited German movement during the daytime. Rocket-firing Typhoons of No. 83 Group flew 294 sorties and P-47s of IX TAC added a further 200. Although the Allied pilots claimed extremely large numbers of German armor destroyed, later battlefield surveys indicated that only nine armored vehicles had been lost to air attack instead of the 120 claimed. But the threat of air attack was as debilitating as actual losses, paralyzing German ground operations. Recollections by German veterans of the battle singled out the “jabos” as their single most fearsome opponent even though infantry anti-tank weapons and artillery caused far higher losses.

Over the next several days, the fighting around Mortain shifted to small unit actions, with GIs and panzer grenadiers bitterly contesting hedges, ruined farms, and road junctions. The 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry remained surrounded on the crest of Hill 317 on the eastern side of Mortain, and the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division could not dislodge them. Some supplies were dropped to the regiment by air, and curiously enough some critical medical supplies were delivered inside hollow artillery projectiles designed for spreading propaganda leaflets. The battalion continued to direct artillery fire on to German positions below, and Hill 317 remained a thorn in the German side through the whole course of the battle.

While the Germans had enjoyed the defensive potential of the bocage for nearly two months, the counterattack towards Avranches put the shoe on the other foot. The GIs of the 30th Division were able to exploit the hedgerows to defend Mortain against the panzer attack, which was conducted with far too little German infantry.

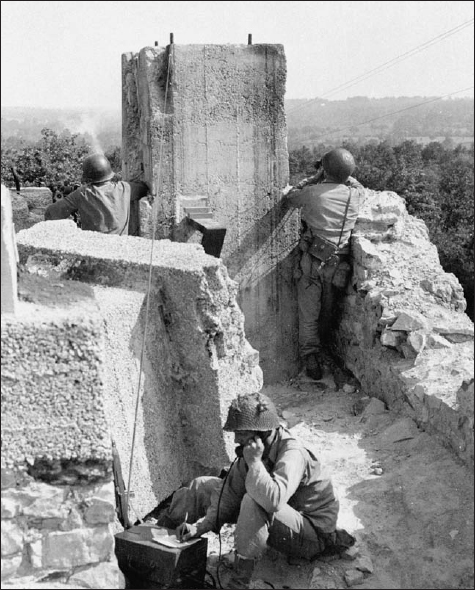

An artillery observation post near Barenton calls in fire on German targets near Mortain during the fighting on 9 August. Smoke from the battle can be seen to the left of the photo.

An officer of 1/117th Infantry, 30th Division uses a field telephone to call for artillery support from a fox-hole in a hedgerow near St. Barthelmy on 11 August 1944. This battalion’s defense of the town against the 1st SS Panzer Division was critical in the defeat of Operation Lüttich. On either side of him are SCR-528 “handie-talkie” radios.

Hitler was furious at the modest gains made by Operation Lüttich, and accused Kluge of a hasty and careless execution of the attack. Schwerin was sacked for his insubordination and replaced by his deputy. Hitler was in a rage, and against his better judgment Kluge ordered three more panzer divisions, the 9th SS, 10th SS and 12th SS Panzer Divisions to begin to disengage from the British sector and to move to the Mortain area.

On the morning of 8 August 1944 the First Canadian Army launched Operation Totalize, an offensive aimed at Falaise, 21 miles south of Caen. For the Allies, the timing of Operation Lüttich could hardly have been better. The Germans had denuded the British sector of panzer units immediately before the Canadian offensive, substantially enhancing the chances for an Allied success near Caen. In a conversation with the commander of Panzer Group West, Gen Heinrich Eberbach, Kluge admitted that “We didn’t expect this to come so soon.” The 10th SS Panzer Division was already on the move to Mortain, but Kluge managed to halt the movement of the other two panzer divisions so that they could resist the Canadian drive.

The next attack at Mortain was scheduled for the evening of 9 August, planning to use the cover of darkness as a shield against the fighter-bombers. This had to be postponed at least a day. Even though the Canadian drive bogged down on 9 August after a penetration of five miles, there was every reason to believe that it would continue. A more ominous development was Patton’s capture of Le Mans, which strongly hinted that the Allies were in the process of carrying out a deep envelopment of the German forces in Normandy. The threat posed by Patton’s Third Army prevented the 9th Panzer Division from joining Operation Lüttich, and it remained in the Alençon area.

While the Germans were attempting to cut off the US forces at Mortain, Bradley was beginning to deploy units to the south at Mayenne to begin the swing eastward to exploit the breakthrough. This is a reconnaissance jeep of the 90th Division on 6 August. The rail at the front of the jeep was intended to cut communication wire across roads that could injure the crew.

The next phase of Operation Lüttich was placed under the command of Heinrich Eberbach, who had been in control of the German forces in the British sector. Hitler expressed confidence that he could succeed, a view not shared by Eberbach. The second assault was to use two corps and would include reserves released by Hitler from the Paris area including additional Nebelwerfer rocket artillery and an additional battalion of Panther tanks. Eberbach wanted to wait until 20 August for the attack, since the waning moon would give his forces the darkness they so desperately wanted. Furthermore, the revised start date of 11 August seemed too soon, since by then Eberbach had only managed to scrape up 47 Panther and 77 PzKpfw IV tanks, little more than had been available during the first failed attack.

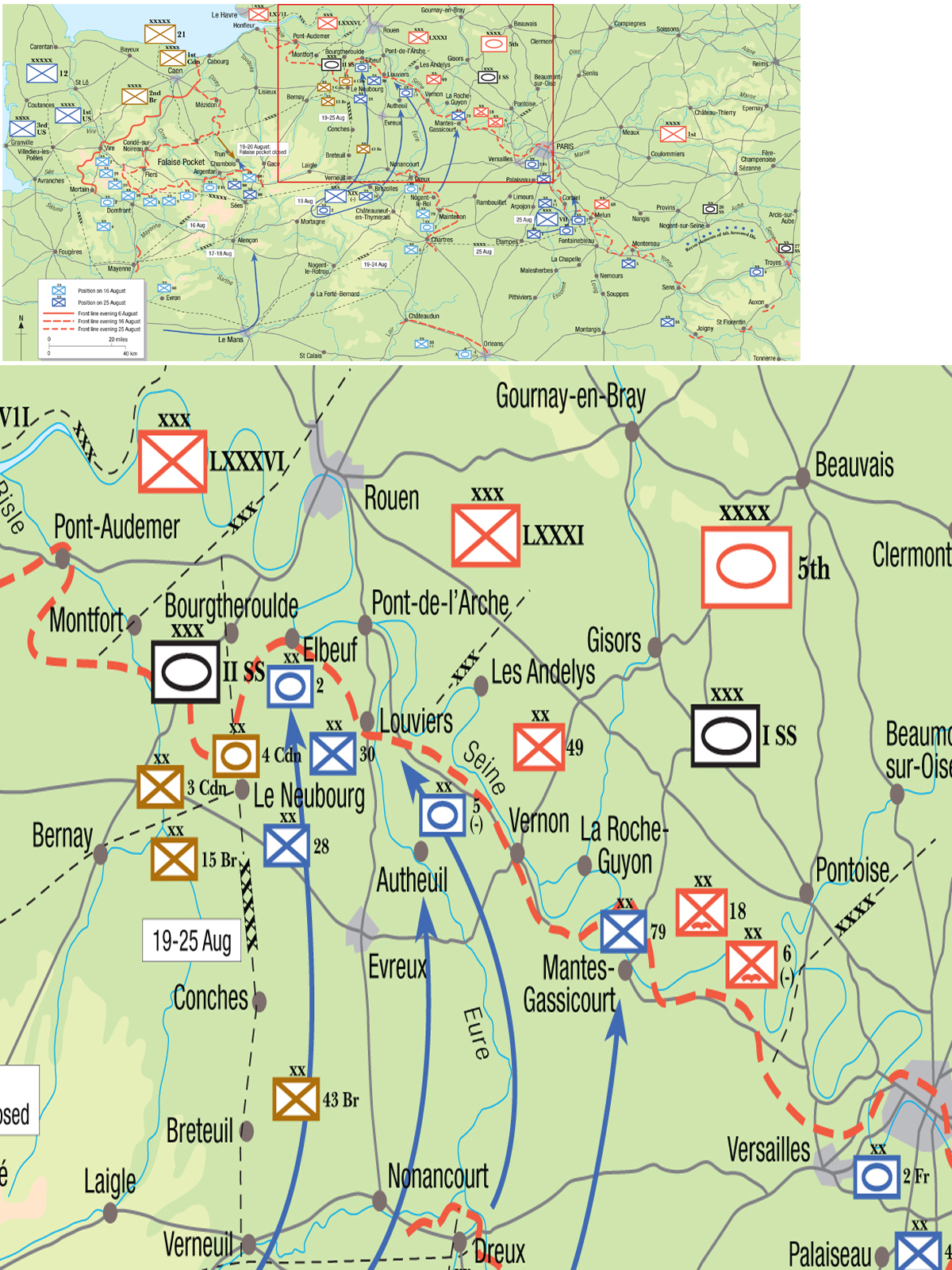

By the evening of 10 August the situation had continued to deteriorate rapidly. The Canadians had resumed their attack and Patton’s XV Corps had begun to swing to the north-east towards Alençon. This suggested that the Allies were indeed trying to trap the German forces in a double pincer. Furthermore, Alençon contained the main German supply dumps for the Normandy sector. In the view of Eberbach and Kluge the prospects for an assault towards Avranches had become sheer fantasy. The US First Army had stopped Operation Lüttich cold and the US 2nd Armored Division had begun to push back the weak 2nd SS Panzer Division. Since the Canadian thrust seemed to be slowing, Patton’s assault towards Alençon seemed the most immediate threat. Kluge requested that the Avranches attack be called off for the time being and that he be given permission to shift two or three panzer divisions to the Alençon region to reinforce the 9th Panzer Division against Patton.

As Kluge had surmised, the Allied drive toward Alençon was indeed a coordinated effort to envelop the German forces in Normandy. Bradley came to realize that the Mortain attack, rather than being much of a threat, presented a superb opportunity. By tying down the last of the German panzer reserves it improved the prospects for success by the Canadians while at the same time minimizing the possibilities of German action against Patton’s forces. While Eisenhower was at Bradley’s field headquarters on 8 August, he telephoned Montgomery to suggest a change in US plans. Instead of moving east towards the Seine the focus of Patton’s Third Army would shift north towards Alençon, and then to the boundary of the 21st Army Group roughly along the line from Carrouges to Sees. At this point, if conditions warranted it Patton’s forces could continue their advance across the inter-army boundary towards Argentan. Montgomery was enthusiastic about the potential for such an operation. Although agreeing with the objectives suggested by Bradley, he suspected that the Germans would concentrate their efforts in the bocage country near Alençon where it would be easier to conduct defensive operations. As a result he pressed the Canadians to pursue their drive on Falaise as rapidly as possible, expecting that they could reach Argentan quicker than the Americans. After this conference Bradley passed instructions to Patton, and also redirected Hodges’ First Army. Instead of moving to the east First Army was to overcome the German forces around Mortain and, using Mortain as a hinge, move northward through Barenton and Domfront towards Flers.

Operation Lüttich led to heavy losses in the attacking German panzer formations. Here a GI inspects a wrecked German SdKfz 251 Ausf. D half-track near Mortain on 12 August. This was the standard armored troop carrier of the panzer-grenadier regiments in Normandy. German units heavily camouflaged their armored vehicles with tree branches in hopes of avoiding the attentions of roving Allied fighter-bombers.

An essential element of Patton’s plan to race for the Seine was the isolation of the battlefield from possible German reinforcements coming from the south. As a result the 9th Tactical Air Force began a campaign to knock down surviving bridges over the Loire. Here B-26 Marauders bomb the Ponts de Cereail at Angers.

By 12 August Collins’ VII Corps had swung north from Mayenne and was forming the southern shoulder of the Falaise pocket opposite the remnants of the German Seventh Army. Here infantry move forward through La Ferté Macé onboard an M4 medium tank.

Patton instructed Haislip to spearhead the XV Corps attack with his armor, and to this end he dispatched the 2nd French Armored Division under Gen Jacques Leclerc to supplement the 5th Armored Division. Opposing XV Corps was the weakened 708th Division and the 9th Panzer Division minus its Panther battalion. The 9th Panzer Division was deployed with its back up against the Alençon supply dumps. The XV Corps attack began on 10 August and a series of sharp tank fights developed on either side of Alençon, with the French 2nd Armored Division to the west, and the 5th Armored Division to the east. The 9th Panzer Division was outflanked and in a bold night move Leclerc’s tanks seized the bridges over the Sarthe through Alençon before dawn on 12 August. Later in the day both armored spearheads were over the Sarthe river driving north towards Argentan. In a day of intense fighting 9th Panzer Division was shattered, and XV Corps knocked out or captured 100 tanks. The main obstacle in the sector was the Forêt d’ Écouves, which would have been nearly impassable if stoutly defended. Rather than risk being trapped in the woods, Leclerc allowed his eastern combat command to use the road through Sees reserved for the westernmost combat command of the 5th Armored Division. The resulting traffic jam slowed down refueling for the 5th Armored Division, and so the spearheads were not able to take Argentan that day. A French column reached the center of town on 13 August, but was quickly pushed out when German tanks arrived in force.

The German situation was quickly growing desperate. Hitler’s planned panzer counteroffensive against the XV Corps had to be reconsidered. Eberbach dispatched the 116th Panzer Division to Avranches to block Patton’s drive north but the main attack had to be postponed again until 14 August. Instead of proceeding south from Carrouges towards Le Mans, the attack was now aimed east through the Forêt d’ Ecouves across the paths of the French 2nd Armored Division and 5th Armored Division. On reaching Mele-sur-Sarthe, Eberbach’s panzer force was to swing north, destroying the two Allied tank spearheads. By the afternoon of 13 August Eberbach had managed to assemble the remnants of the 1st SS Panzer Division, the 2nd Panzer Division, and the 116th Panzer Division in the Argentan area. However, their total strength was only about 70 tanks, not enough to execute an attack on two full-strength Allied armored divisions. German commanders, starting with the head the Fifth Panzer Army, Sepp Dietrich, began arguing that it was time to consider pulling forces out of the noose, not ordering them to their certain doom.

A turning point in the summer fighting came on 15 August. Landings by the US Seventh Army on the southern coast of France threatened to envelop remaining German forces along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, forcing a general German withdrawal from the rest of France. Here M4A1 Duplex Drive amphibious tanks are disgorged from an LST near St. Tropez during Operation Dragoon.

August 13 was a turning-point in the final Normandy battles. While the Germans were beginning to question their strategic options, so too were the Allies. On 13 August Bradley ordered Patton to redirect his corps eastward, rather than north into the Argentan–Falaise gap. This decision was later the source of considerable controversy since by not immediately closing the 20-mile gap, the Allies let a significant number of German troops escape. Bradley’s reasons were straightforward. Patton’s troops were already north of the inter-army boundary which had been allotted to the British 21st Army Group. Bradley was concerned that a head-on meeting of the American and Canadian forces would lead to serious “friendly fire” problems, and complicate air-support missions. Even though XV Corps had seized Argentan without heavy loss, their position was far from secure. Bradley stated that he would prefer a “solid shoulder at Argentan than a broken neck at Falaise.” XV Corps had its neck stuck out without secure flanks. To the west, Eberbach’s forces were on the verge of launching a panzer counterattack designed specifically to cut off the armored spearhead at Argentan, and there was a 20-mile gap separating XV Corps and the advancing elements of the US First Army further west. Bradley’s decision was also based on false intelligence estimates that the Germans were already withdrawing the bulk of their forces from the Falaise pocket. The Allied commanders found it hard to believe that the Germans would be stupid enough to allow the bulk of their forces in Normandy to be trapped. Bradley’s move instead aimed to eliminate the remaining German forces by a deeper envelopment on the Seine.

The 7th Armored Division surged past the cathedral city of Chartres on 16 August. The M4A1 from the 31st Tank Battalion on the left is fitted with a Rhino, while the M4 (105mm) assault gun to the right is not.

In spite of the looming catastrophe, Hitler continued to demand that Eberbach launch a panzer counterattack to cut off XV Corps. But by this time Eberbach’s force was down to 44 tanks and 13 assault guns, hardly the makings of a decisive force. Hitler did accede to a withdrawal to a shorter defense line near Flers, but this would have occurred with or without his acceptance given the weakness of German forces in the area. Kluge drove to Dietrich’s headquarters on 14 August and was told quite bluntly that the Fifth Panzer Army could no longer contain the Canadian drive. Dietrich strongly recommended the withdrawal of German forces from the Falaise pocket as quickly as possible or risk losing the German army in Normandy. Kluge left Dietrich’s headquarters the next day for a meeting with Hausser and Eberbach but vanished.

The Canadian attack towards Falaise was having a rough time but on 14 August was reinvigorated by another carpet-bombing. Falaise was finally taken on 16 August leaving just a 15-mile gap between the Allied spearheads. As the Canadian forces moved southward Hodges’ US First Army continued pressure to the north and east, overrunning the staging area for Eberbach’s perpetually delayed panzer attack. On 15 August another lightning bolt struck. The US Seventh Army landed on the southern coast of France near Marseilles, largely unopposed. This would tie down remaining German forces in Army Group G, and threaten to cut off all German forces in the remainder of southern and central France.

The German commanders in Normandy, with Kluge still missing, had come to the conclusion that an immediate withdrawal was essential. The German high command remained unconvinced and Jodl continued to insist that the only solution was a German counterattack. This was complete fantasy as by this stage the German panzer units were low on fuel, under constant pressure from Allied artillery and air attack, and the roads were jammed with units attempting to withdraw. One officer compared the situation to Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. Hitler reiterated the demand for an attack on the XV Corps spearhead. Kluge finally showed up on the evening of 15 August stating that his car had been strafed and his radio put out of action. At 02.00 on 16 August he informed the high command that in his judgment his panzer forces were insufficient for a counterattack and that fuel shortages had reached a critical stage. After a series of exchanges Jodl finally agreed and promised that an authorization from Hitler would be forthcoming. Having heard nothing at 14.40 an impatient Kluge issued his own withdrawal order. Hitler’s permission finally arrived two hours later but contained the demand that Panzer Group Eberbach widen the exit by a panzer strike against XV Corps at Argentan. German troops began the move out of the Falaise pocket after sunset on 16 August 1944. The remnants of 2nd SS Panzer Division and 116th Panzer Division launched an attack against the 90th Division roadblocks in the village of Le Bourg-St. Leonard, hoping to knock the Americans off a ridgeline that had vistas over the escape routes further north. The attack did seize the ridge but it was retaken by American infantry that night. A day-long battle for control of the area followed. This feeble attack was the last gasp of Operation Lüttich. Hitler finally accepted the gravity of the situation and ordered all non-combat troops in Army Group G in western and southern France to begin a withdrawal behind the Seine river.