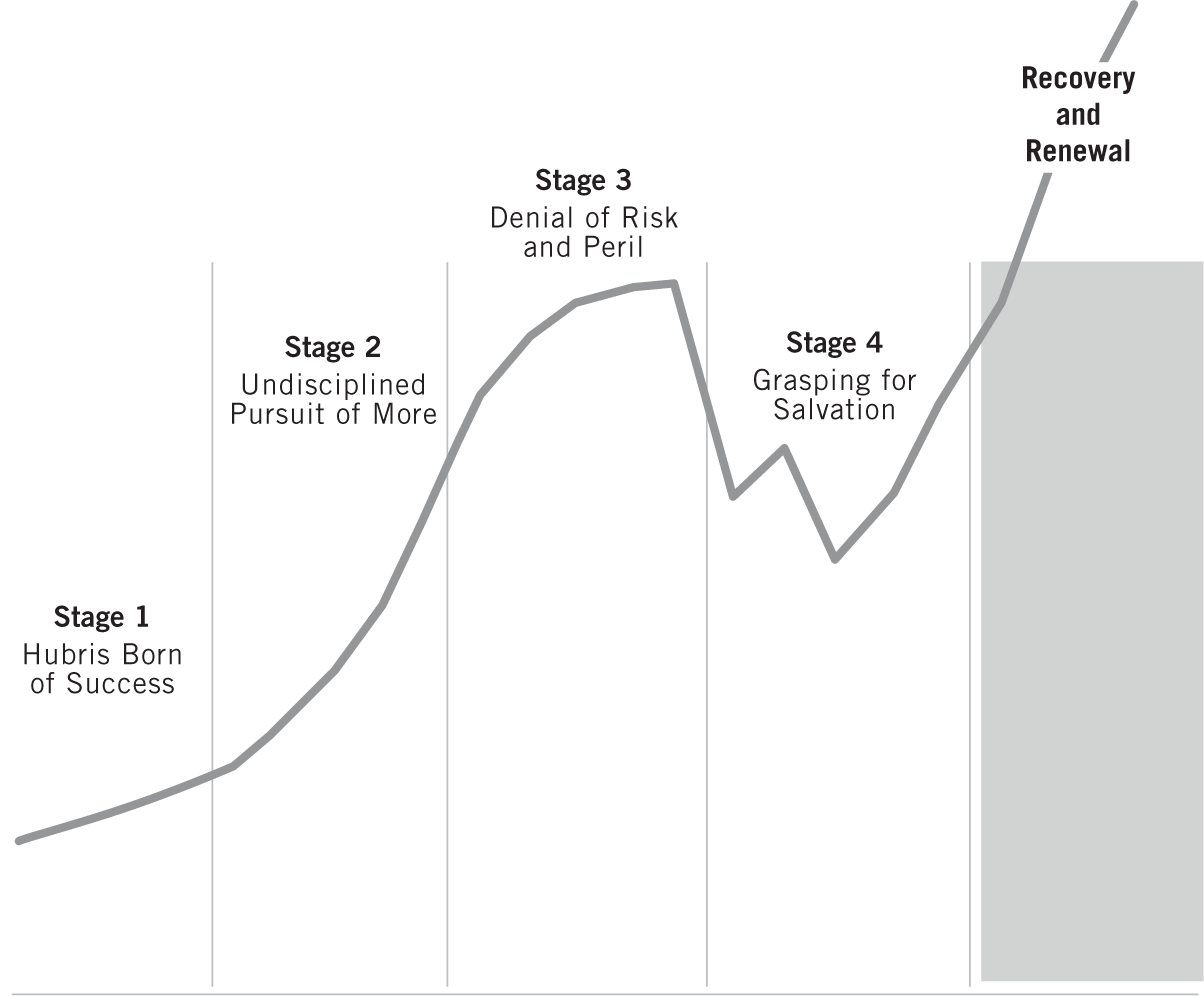

If we discovered that organizational decline is a function first and foremost of forces out of our control—and if we discovered that those who fall will inevitably keep falling to their doom—we could rightly indulge in despair. But that is not our conclusion from this analysis, not if you catch decline in Stages 1, 2, or 3. And in some cases, you might even be able to reverse course once in Stage 4, as long as you still have enough resources to get out of the cycle of grasping and rebuild one step at a time.

When Anne Mulcahy became chief executive of Xerox in 2001, she inherited a company mired in Stage 4. Digesting a $273 million loss, Xerox stock had dropped 92 percent in less than two years, wiping out more than $38 billion in shareholder value. With Xerox’s debt-to-equity ratio exceeding 900 percent, Moody’s rated its bonds as junk. The Securities and Exchange Commission had launched an investigation into Xerox’s books, which precluded Xerox from registering any securities and limited its fundraising options. With $19 billion in debt and only $100 million in cash, Mulcahy described the situation as “terrifying.” Prior to Mulcahy’s appointment, Xerox had strived to reinvent itself for the Digital Age, hiring superstar Richard Thoman from IBM (where he’d been a valued member of Gerstner’s team) to succeed CEO Paul Allaire, who remained chairman. “We were looking for a change agent,” Allaire said of the decision to go outside. But Thoman lasted only thirteen months as CEO.152

In May 2000, Mulcahy had finished packing for a business trip to Tokyo when Allaire asked her to come to his office right away. “Here’s the deal,” said Allaire. “Rick’s [Thoman] out. I’m coming back in as CEO, and I want you to be president and COO of Xerox, and a year later, if things are right, you’ll be CEO.”153

Mulcahy had never planned or expected to become CEO, describing her ascension as a total surprise.154 “The board probably sat back and said, ‘What choice do we have?’ So I can’t say it was a roaring endorsement,” Mulcahy later told writer Kevin Maney. “It probably was a little bit of a last resort.”155 The consummate insider, she’d worked nearly a quarter of a century at Xerox in sales and human resources, never drawing outside attention; Mulcahy didn’t even appear in Fortune magazine’s “50 Most Powerful Women in Business” ranking the year before becoming president.156

Mulcahy could have perpetuated a Stage 4 doom loop by setting forth to utterly smash the culture and revolutionize the company overnight. But instead, she retorted to those who said she would need to kill the culture to save the company, “I am the culture. If I can’t figure out how to bring the culture with me, I’m the wrong person for the job.”157 For Mulcahy, it was all about Xerox, not about her. When Newsweek called her, Mulcahy declined to be interviewed about her management style.158 In fact, we found only four feature articles about Mulcahy during her first three years as CEO, a surprisingly small number, given how few women become CEO of storied Fortune 500 companies.159

Some observers questioned whether this insider, this unknown team player who had Xerox DNA baked into her chromosomes, would have the ferocious will needed to save the company.160 They needn’t have worried. Their first clue might have come in reading her favorite book, Caroline Alexander’s The Endurance, which chronicles how, against all odds, adventurer Ernest Shackleton rescued his men after their ship splintered into thousands of pieces as Antarctic ice crushed in around it in 1916. Accompanied by five crew members, Shackleton navigated 800 miles of violent seas in a 22-foot lifeboat to find help for the remaining survivors.161 Drawing inspiration from Shackleton, Mulcahy didn’t take a weekend off for two years.162 She shut down a number of businesses, including the inkjet-printer unit that she’d championed earlier in her career, and cut $2.5 billion out of Xerox’s cost structure. Not that she found these decisions easy—“I don’t think I want them to get easy,” she later reflected—but they were necessary to stave off utter catastrophe.163 During its darkest days, Xerox faced the very real threat of bankruptcy, yet Mulcahy rebuffed with steely silence her advisors’ repeated suggestions that she consider Chapter 11. She also held fast against a torrent of advice from outsiders to cut R&D to save the company, noting that a return to greatness depended on both tough cost cutting and long-term investment, and actually increased R&D as a percentage of sales during the darkest days. “For me, this was all about having a company that people could retire from, having a company that their kids could come and work at, having a company that actually would have pride some day in terms of its accomplishments.”164

For 2000 and 2001, Xerox posted a total of nearly $367 million in losses. By 2006, Xerox posted profits in excess of $1 billion and sported a much stronger balance sheet. And in 2008, Chief Executive magazine selected Mulcahy as chief executive of the year. At the time of this writing in 2008, Xerox’s transition had been going strong for seven years—no guarantee, of course, that Xerox will continue to climb, but an impressive recovery from the early 2000s.165

Xerox. Nucor. IBM. Texas Instruments. Pitney Bowes. Nordstrom. Disney. Boeing. HP. Merck. What do these companies have in common? Every one took at least one tremendous fall at some point in its history and recovered. Sometimes the tumble came early, when they were small and vulnerable, and sometimes the tumble came when they were large, established enterprises. But in every case, leaders emerged who broke the trajectory of decline and simply refused to give up on the idea of not only survival, but of ultimate triumph despite the most extreme odds. And like Mulcahy, these leaders used decline as a catalyst. As Dick Clark, the quiet, longtime head of Merck manufacturing who became CEO after Gilmartin, put it, “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.”166

If you have not yet fallen, beware the temptation to proclaim a crisis when none exists. Recall the Gerstner philosophy: the right leaders feel a sense of urgency in good times and bad, whether facing threat or opportunity, no matter what. They’re obsessed, afflicted with a creative compulsion and inner drive for progress—burning hot coals in the stomach—that remain constant whether facing threat or not. To manufacture a crisis when none exists, to shriek that we’re all standing on a “burning platform” soon to collapse in a spectacular conflagration, creates cynicism. The right people will drive improvement, whether standing on a burning platform or not, and they never take well to manipulation.

And if you’ve already taken a fall and you do face a genuine crisis, the sooner you break the cycle of grasping for salvation the better. The path to recovery lies first and foremost in returning to sound management practices and rigorous strategic thinking. In Appendix 6, I’ve outlined three cases of great companies that fell and recovered (IBM, Nucor, and Nordstrom), and I’ve laid out their recovery through the lens of the good-to-great framework of disciplines (summarized in Appendix 7). If you seek a refresher course on management discipline, it never hurts to review the classics, including Drucker, Porter, Deming, and Peters/Waterman. Of course, you have to stop the bleeding first and make sure you don’t run out of cash, but that’s simply emergency surgery, not full recovery. The point being, however you slice it, lack of management discipline correlates with decline, and passionate adherence to management discipline correlates with recovery and ascent.

All that said, there remains a question: what about “the perennial gale of creative destruction” as described by the famous twentieth-century economist Joseph Schumpeter, wherein technological change and visionary entrepreneurs upend and destroy the old order and create a new order, only to see their new order destroyed and replaced by an even newer order, in an endless cycle of chaos and upheaval?167 Perhaps all social institutions in our modern world face disruptive forces so fast, big, and unpredictable that every entity will fall within years or decades, without exception. Can we still stave off decline in the face of severe turbulence?

While working on How the Mighty Fall, my colleague Morten Hansen and I have been simultaneously working on a six-year research project to study companies that grew from vulnerability to greatness in severe environments characterized by rapid and unpredictable change in contrast to others that did not prevail in the same brutally turbulent environments. Consider the following analogy: Suppose you wake up in base camp at the foot of Mount Everest and a big storm rolls through. You can hunker down in the safety of your tent and let the storm pass by. But if you wake up as a vulnerable little speck at 27,000 feet on the side of the mountain, where the storms are bigger and faster moving, the environment severe and unforgiving, and everything more uncertain and uncontrollable, then a storm just might kill you. We believe most leaders in every sector feel they are metaphorically moving higher on the mountain, into increasingly turbulent and unforgiving environments.

This new research is enlarging our understanding of the principles and strategies needed to prevail in a turbulent world, and I’d like to preview a key conclusion here, one that pertains directly to the question of corporate decline. When the world spins out of control, when external tumult threatens to upend our best-laid plans, does our destiny remain in our own hands? Or must we accept that creative destruction reigns supreme and that success will be short and fleeting, even for the very best? Our research shows that it is possible to build a great institution that sustains exceptional performance for multiple decades, perhaps longer, even in the face of chaos, disruption, uncertainty, and violent change. In fact, our research shows that if you’ve been practicing the principles of greatness all the way along, you should get down on your knees and pray for severe turbulence, for that’s when you can pull even further ahead of those who lack your relentless intensity. But beware: if you get caught in the stages of decline during turbulent times—if you succumb to hubris, overreaching, denial, and grasping for quick fixes—your fall will be faster and more violent than in stable times. The nearly overnight demise of some of America’s largest financial companies in 2008 illustrates just how fast the mighty can fall in a highly turbulent world.

If you’ve fallen into decline, get back to solid management disciplines—now! And if you’re still strong, be vigilant for early markers of decline. But above all, do not ever capitulate to the idea that an era of success must inevitably be followed by decline and demise brought on by forces outside your control. The matched-pair contrast method that we employ in our research (comparing successful outcomes to unsuccessful outcomes, controlling as much as possible to pick similar companies facing similar environmental conditions) yields an important insight: circumstances alone do not determine outcomes. Of course, there always remains the chance of a random catastrophe, and life offers no 100 percent guarantees; after all, you can be the healthiest, most relentless athlete of all time and still be stricken with a crippling disease or career-ending accident. But setting that aside, the main message of our work remains: we are not imprisoned by our circumstances, our setbacks, our history, our mistakes, or even staggering defeats along the way. We are freed by our choices.

The signature of the truly great versus the merely successful is not the absence of difficulty, but the ability to come back from setbacks, even cataclysmic catastrophes, stronger than before. Great nations can decline and recover. Great companies can fall and recover. Great social institutions can fall and recover. And great individuals can fall and recover. As long as you never get entirely knocked out of the game, there remains always hope.

We all need beacons of light as we struggle with the inevitable setbacks of life and work. For me, that light has often come from studying Winston Churchill. In the early 1930s, Churchill’s career had descended into what biographer Virginia Cowles called “a quagmire from which there seemed to be no rescue.” Entering his late fifties, fattening up, and losing hair, he’d been widely blamed for Britain’s financial dislocation in the Depression, having put Britain back on the gold standard as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He’d broken with his party, isolating himself from the mainstream by his opposition to Indian self-rule, refusing even to meet with Gandhi. He’d been forever tagged as the architect of the World War I tragedy at Gallipoli (a botched plan to knock Turkey out of the war, and to attack Germany and Austria from the southeast), which cost 213,980 British casualties for zero gain; even though the Dardanelles Commission cleared him of blame, he remained tainted by the disaster. The 1929 stock market crash cost Churchill a considerable fortune. And on December 12, 1931, he stepped off a curb on Fifth Avenue in New York, looking to his right to check for traffic as he would in London rather than to his left as he needed to in America. Passers-by heard a sickening “thwaump!” as a car driving more than 30 miles per hour blindsided Churchill, knocking him yards down Fifth Avenue. The accident threw him into the hospital, a long recovery, and a severe depression.168

At the end of Volume I of his series, The Last Lion, William Manchester captures Churchill’s position in 1932. Lady Astor visited with Joseph Stalin, who quizzed her on the political landscape in Britain. Astor prattled on about the powerful, the up-and-coming, naming Neville Chamberlain as the star.

“What about Churchill?” asked Stalin.

“Churchill?” Astor’s eyes widened. Then with a disdainful wrinkle of her nose, “Oh, he’s finished.”169

Eight years later, on June 4, 1940, Churchill stood in front of Parliament as prime minister while Hitler’s Panzer divisions swept across France. Poland: gone. Belgium: gone. Holland: gone. Norway: gone. Denmark: gone. France: collapsing. England: reeling from the rout leading up to the evacuation from Dunkirk. Most world leaders, including many in Britain, saw no choice but to cede Europe to the Nazis. Churchill’s rivals expected Churchill to see no other alternative than a negotiated peace with Herr Hitler and his Nazi henchmen, and they hoped to capitalize on his taking the political fallout for capitulation.

They were to be disappointed.

Clutching his notes, for he always feared that without his carefully prepared text he would be at a loss for words, Churchill glowered out across the House of Commons and issued his famous words, “We shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”170

Not only would Churchill redeem himself by giving voice to Britain’s resolve to stand against the Axis powers, he would also go on to win the Nobel Prize in literature, return again as prime minister at age seventy-seven, be knighted by the Queen, and sear into Cold War lexicon the term “Iron Curtain” in his prescient warning about Soviet aggression.

In 1941, during England’s sternest days, Churchill returned to his old school, Harrow, where he’d received embarrassingly low scores, to give a commencement address. The headmaster cast worried glances at Churchill, who had fallen asleep, slumbering through most of the ceremony. But when introduced, Churchill made his way to the podium, stared out over the assemblage of boys, and gave his commencement message, “This is the lesson: never give in, never give in, never, never, never, never—in nothing, great or small, large or petty—never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force; never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.”171

Never give in. Be willing to change tactics, but never give up your core purpose. Be willing to kill failed business ideas, even to shutter big operations you’ve been in for a long time, but never give up on the idea of building a great company. Be willing to evolve into an entirely different portfolio of activities, even to the point of zero overlap with what you do today, but never give up on the principles that define your culture. Be willing to embrace the inevitability of creative destruction, but never give up on the discipline to create your own future. Be willing to embrace loss, to endure pain, to temporarily lose freedoms, but never give up faith in the ability to prevail. Be willing to form alliances with former adversaries, to accept necessary compromise, but never—ever—give up on your core values.

The path out of darkness begins with those exasperatingly persistent individuals who are constitutionally incapable of capitulation. It’s one thing to suffer a staggering defeat—as will likely happen to every enduring business and social enterprise at some point in its history—and entirely another to give up on the values and aspirations that make the protracted struggle worthwhile. Failure is not so much a physical state as a state of mind; success is falling down, and getting up one more time, without end.