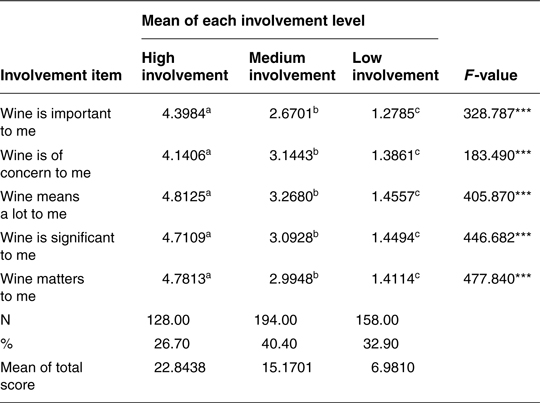

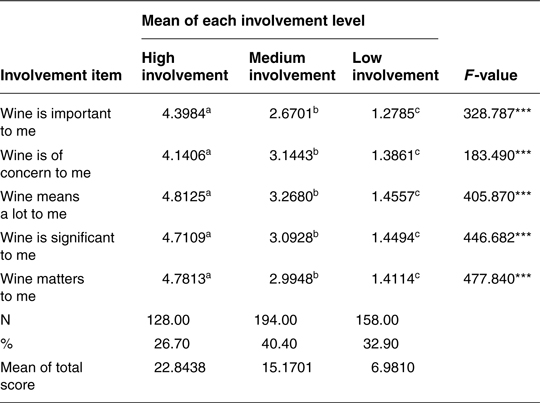

Table 10.1 Level of personal involvement with wine

*** Significance level at p < 0.001 level.

a,b,c The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

Chapter 10

Segmenting Wine Festival Visitors Using their Personal Involvement with Wine

In recent years, wine festivals have become popular in many regions. Wine festivals present a unique synergy between wine, special events, and travel activities, adding value to the tourism development of a wine region (Salter, 1998; Yuan et al., 2005). Wine-related events attract visitors and give opportunities for wineries and wine regions to promote the destination and products (Getz, 2000; Hoffman et al., 2001; Houghton, 2001). Having a good time at a wine festival, visitors leave with a positive image of the wine and/or the wine tourism region. This image may then lead to future purchase of the product and re-visitation. Wine festivals have increasingly become an effective promotional strategy for wine regions, attracting a wider audience than wineries alone (Collins, 1996).

Visiting wine festivals is one activity encompassed within wine tourism, which incorporates service provision and destination marketing (Getz and Brown, 2005). In this process, wineries and winegrowing regions provide the core products, namely the wine and the tourist attractions, whereas wine festivals are developed to promote and to enhance the awareness of these products. By partnering together to stage a regional event, wineries develop a high profile opportunity to market their products to the wider community (Beverland et al., 2001). Wine festivals therefore play an important role in selling wine brands, promoting the attractiveness of wine-growing regions, and helping build customer loyalty towards individual wineries. It is then important to understand the nature of wine festival visitors and their segmentation in order to develop appropriate promotional strategies. Wine festivals, if taking place at convenient locations, may attract attendees who do not intend to visit any winery or winegrowing region and thereby would never be ascribed to the category of wine tourists.

The current research was conducted to develop a typology of visitors attending a regional wine festival. The purposes of the research were as follows:

Personal Involvement with Wine as a Segmentation Tool

The concept of involvement has been identified as an important factor in explaining consumer behaviour since Krugman (1965) introduced the term to consumer psychology. Numerous studies have since then been produced in a wide variety of consumer-related research. Yet one underlying theme appears to remain constant. Involvement is postulated as the consumer’s perceived importance or relevance for an object, such as a product, based on inherent needs, value, and interest. For example, Antil (1986), on the basis of the inherent interrelationship of involvement components, defined involvement as the level of perceived personal importance and/or interest evoked by a stimulus (or stimuli). The stimulus may refer to a product class. Involvement is then conceptualized as interest in or perception of importance of a particular product category (Zaichkowsky, 1985), such as wine.

The level of personal involvement with wine demonstrates a wine consumer’s generic feelings of importance and relevance with the product class. It also reflects his or her genuine level of interest in wine on a daily basis. The concept captures a wine consumer’s feelings of interest, enthusiasm, and excitement about the product category. Personal involvement with wine reflects an underlying aspect of a wine consumer’s lifestyle. It is determined by an individual’s inherent value system as well as his or her unique experiences.

Lockshin et al. (1997) asserted that wine consumers could be ascribed into two different groups: those involved in wine and those not involved in wine. Highly involved wine consumers are wine enthusiasts. These individuals relate to wine as part of their lifestyle where it holds an important place in their daily lives. According to Lockshin (2001), these individuals often spend considerable time reading specialty magazines, lingering in the retail stores, talking to sales people and discussing their hobby with friends. Wine becomes a pursuit of pleasure for an individual. Wine enthusiasts take approximately one-third of wine consumers, but buy more wine and spend more per bottle than low involvement buyers. When visiting wineries, a study by Dodd and Gustafson (1997) found that there was a positive relationship between product and purchase involvement and wine purchase. In addition, there was a positive relationship between product involvement and purchase of souvenirs.

Meanwhile, in the wine tourism research area, it has also been realized that wine tourists are not alike in terms of their needs, wants, and personal characteristics. They should be treated as heterogeneous groups. There have been attempts to classify wine tourists and a variety of segments have been produced in different parts of the world:

Western Australia – Ali-Knight and Charters (1999)

British Columbia – Williams and Dossa (2003)

Italy – Movimento del Turismo del Vino study, 1996 (cited in Cambourne and Macionis, 2000)

New Zealand – Hall (1996)

Texas – Dodd and Bigotte (1997)

Charters and Ali-Knight (2002) continued with the research effort. They asked respondents in two wine regions of Western Australia to self-classify on the basis of their interest in and knowledge of wine. This classification produced four groups – the wine lover (the ‘highly interested’), the wine interested (the ‘interested’), the wine novice (those with limited interest), and the ‘hangers on,’ a marginal group who went to wineries with no apparent interest in wine, but as a part of a group. The previous educational experience of different segments varied, with the wine lovers having a more comprehensive grounding in wine.

A more recent and comprehensive review of the post-visit consumer behaviour of New Zealand winery visitors by Mitchell and Hall (2004) also identified a number of segments. In their study, a higher propensity for brand loyalty (i.e. post-visit purchase and repeat visitation) was found among those with intermediate or advanced wine knowledge, and those drinking wine more frequently and purchasing more wine. More importantly, brand loyal behaviour was found in repeat visitors to wineries and those who purchased wine during the visit. The findings suggest that routine wine consumption is part of a wider relationship with winery and its wine.

Can wine festival visitors be segmented on the basis of their personal involvement with (i.e. their interest level in) wine? If so, will there be any differences exhibited between the market niches related to their socio-demographic characteristics, travel motivations, and other trip behaviours related to the festival?

Previous examinations of wine event goers suggest that wine festivals largely attract wine enthusiasts who would pay repeat visits to the event (Weiler et al., 2004). It is therefore noteworthy to investigate the motivation and satisfaction characteristics of different segments among the festival goers. This exploration would help wine destination marketing and management to develop a more comprehensive understanding of wine festivals and their catalyst effect on repeat wine tourism (Taylor, 2006).

Promoting Wine Tourism with Wine Festivals

By fully understanding what their customers want, wine regions can provide the total wine tourism experience in a number of ways, the most notable being cultural heritage, hospitality, education, and festivals and events (Charters and Ali-Knight, 2002). Wine festivals are the cultural resources of an area and also create a one-stop shopping opportunity to sample wines from a particular region (Hoffman et al., 2001). Attending festivals is recognized as the main reason and specific motivation for visiting wineries or wine regions (Hall and Macionis, 1998). Yuan et al. (2005) defined a wine festival, from the consumer’s perspective, as a special occasion that attendees ‘actively engage in for the satisfaction of their interest in wine and/or for the entertainment made available by other leisure activities’ (p. 39).

According to Arnold (1999), there are six reasons for staging festivals: revenue generation, community spirit, recreation/entertainment, social interaction, culture/education, and tourism. As opposed to site or permanent attractions, festivals can be developed at places convenient to the market. Hosting festivals to encourage tourist visitation is an increasingly common phenomenon (Derrett, 2004). Because of their intrinsic uniqueness, festivals often create an image that will help attract tourists to a destination (Getz, 1997). The image associated with the event is transferred to the destination, thereby strengthening, enhancing, or changing the destination’s brand (Jago et al., 2003). In recent years, festivals have become a viable component of both the wine and wine tourism industries. When marketing a winegrowing region as tourist destination, festivals offer an extremely good tool for stimulating and increasing awareness and interest in the area (Getz, 2000; Getz and Brown, 2005).

Similarly, wine festival visitors are not alike in terms of their needs, wants, and personal characteristics. They should not be considered as being a homogenous group. It is important for festival organizers and wine marketers to recognize these different groups in order to implement appropriate promotional strategies. Yuan et al. (2005) made an initial attempt in their study to segment wine festival visitors on the basis of attendance motivations. They identified three different types of wine festival attendees, namely ‘wine focusers’, ‘festivity seekers’, and ‘hangers-on’. The wine focusers was the wine-intensive group, whose members seemed the most highly interested in wine. They were purpose driven and pursued the wine theme when attending the festival. Their motivations were very much focused on the wine. The hangers-on had limited interest in wine and this was not the reason for attending the festival. This group had no particular goals in seeking the festival’s leisure experience. The festivity seekers searched for a more diversified or integrated experience incorporating wine, food, environment, setting, learning, and cultural aspects. The festivity seekers may have an interest in wine, but their participation also involved savouring the total experience with wine at the festival.

The purpose of this study was to explore the segmentation of wine festival visitors using their personal involvement with wine and to examine their demographics and some festival-related characteristics of each segment, such as their motivations to attend the wine festival, their evaluation of the festival quality, their satisfaction, value perception, and behavioural intentions.

Research Method

Data Collection

A visitor survey was conducted at the 2003 Vintage Indiana Wine and Food Festival, a 1-day event organized by the Indiana Wine Grape Council which took place in downtown Indianapolis. It is Indiana’s only statewide wine and food festival and was initiated in June 2000. The 2003 event featured live music, a variety of foods presented by local restaurants, wine and food educational sessions. More than 6,000 visitors attended the event in 2003. Ten trained field workers intercepted the attendees on the site of the festival with the survey. Only visitors above 21 years old were approached and a total of 501 useable questionnaires were collected.

Involvement and its Measurement

The core variable in this study was personal involvement with wine. Research on involvement has long been conducted in the field of consumer studies, among which a five-item measurement scale, the Personal Involvement Inventory (PII), was developed and validated (Zaichkowsky, 1985; Mittal, 1995). PII has become one of the more widely used self-report measures in marketing research on involvement. It is effective in identifying product enthusiasts and provides direction to marketing strategy aimed at involved customers.

When being applied to classifying wine consumers, this multi-item scale incorporated five pairs of seven-point bipolar descriptive expressions: wine (to the subject) is (1) important/unimportant, (2) of concern/of no concern at all, (3) means a lot/means nothing, (4) significant/insignificant, and (5) matters/does not matter at all. The total score on the five items was secured to denote the overall degree of personal involvement with wine. Wine festival visitors were subsequently segmented into the high wine involvement, medium wine involvement, and low wine involvement groups. Differences between the involvement groups were then examined. These differences pertained to the visitors’ motivations to attend the festival, their quality perception of the event, their satisfaction and value perception as well as their behavioural intentions. Demographic characteristics of each segment, including age, gender, marital status, income, and education, were also checked.

Other Variables and their Measurements

A total of 25 elements were generated to measure motivations to visit the wine festival. Respondents were asked to indicate the importance of the reasons on a seven-point scale where 1 = not at all important and 7 = extremely important. The 25 motivational elements were further factor analysed and the analysis produced a four-factor solution. The four dimensions were named as: (1) festival and escape, (2) wine, (3) socialization, and (4) family togetherness. Nineteen motivational items were retained in this process.

Twelve items were used to assess perceived quality of the wine festival on a seven-point scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. A factor analysis was performed to reduce the 12 variables to three perceived quality dimensions labelled as (1) facility, (2) wine, and (3) organization. One quality perception item was deleted in the analysis.

Seven-point scales were employed to evaluate festival attendees’ overall satisfaction with the visit (1 = very dissatisfied; 7 = very satisfied) and their experience at the festival in terms of value for money (1 = very poor; 7 = very good). Three behavioural intentions were examined: (1) intention to return to the festival next year (1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely), (2) likelihood of buying local wines after the wine festival (1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely), and (3) possibility of future visitation to a local winery after the wine festival (1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely).

The Analysis

The summed scores on the five-item PII ranged from 5 to 35 with an overall average of 14.52 (SD = 6.83). In order to assess the dimensionality of the involvement scale applied in this study, an exploratory factor analysis was performed. A single factor solution was reached, explaining 73.92 per cent of the total variance. Coefficient alpha in the reliability test was 0.906. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.853. It was therefore justified to combine the five PII items to form a total involvement score. In her research, Zaichkowsky (1985) used the overall distribution derived from data collected from 751 subjects to classify the scorers into either low-, medium-, or high-involvement subgroups. Her approach was chosen by the current study as the baseline for the segmentation of the festival visitors. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests followed to detect possible differences between the involvement groups in regard with their motivations, quality perceptions, overall satisfaction, value perception, and behavioural intentions. Finally, �2 tests were conducted to trace the demographic differences between the involvement groups.

Results and Discussion

Sample Description

About 76 per cent of the respondents at the festival had college or above degrees. Nearly 69 per cent had annual household incomes of more than $40,000. The respondents were younger than the average wine consumers, as 29.5 per cent of them were in the 21–29 age group and another 22.6 per cent in 30–39 category; and a total of 74.1 per cent were less than 50 years old. The percentages of male and female respondents were 35.9 and 63.7, respectively. Married (53.3 per cent) and not married (46.5 per cent) respondents were nearly evenly split.

Involvement Segments

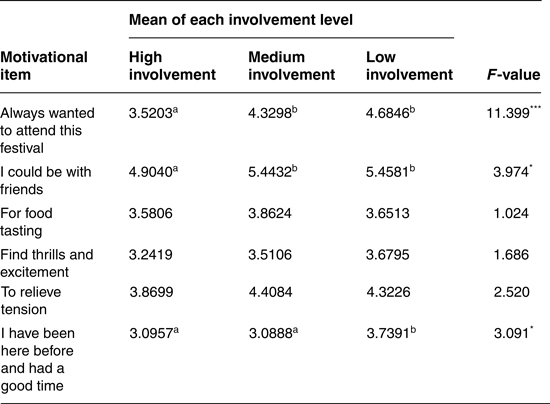

The low involvement cluster was defined as those scoring in the first quartile of the distribution; they had scores ranging from 5 to 10. The medium involvement group was made up of those scoring in the middle 50 per cent of the distribution; they had scores from 11 to 19. High involvement segment consisted of those in the upper quartile of the distribution; they had scores from 20 to 35. Of the 480 valid subjects, 158 (32.9 per cent) had low involvement, 194 (40.4 per cent) displayed medium involvement, and 128 (26.7 per cent) showed high involvement. The mean scores of the five PII items all differed significantly between the three involvement groups (see Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Level of personal involvement with wine

*** Significance level at p < 0.001 level.

a,b,c The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

Involvement and Motivations

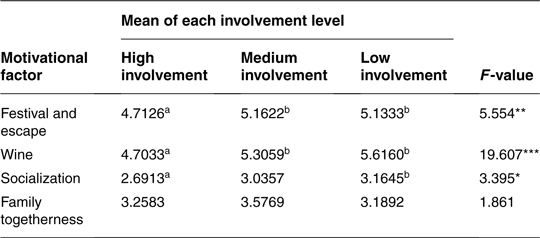

Of the four motivational factors, three showcased significant differences (see Table 10.2). The high involvement segment differed from the other two groups in terms of ‘festival and escape’ and ‘wine’. The difference was particularly evident in the dimension of wine. The high involvement segment also had different mean value on ‘socialization’ from the low involvement group. No difference was revealed on ‘family togetherness’.

Table 10.2 Wine involvement level and motivational factors to attend the wine festival

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.005 level.

*** Significance level at p < 0.001 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

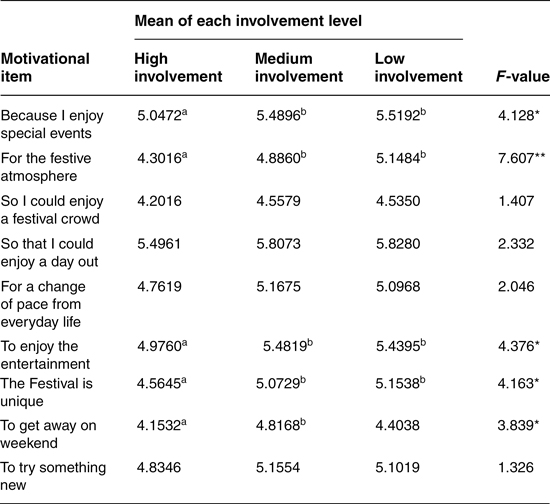

In order to present a better picture of the differences, items within each motivational dimension were compared, with the exception of those factored in ‘family togetherness’. Table 10.3 displayed the results concerning the ‘festival & escape’ items. The high involvement group was found to give substantially lower scores than the other two involvement groups to five out of the nine items. The low and medium involvement groups wanted more than these high scorers to enjoy the special event, the festive atmosphere, the entertainment, and the uniqueness of the festival. In addition, the medium involvement segment desired a weekend getaway at the festival more than did the high involvement group.

Table 10.3 Wine involvement level and motivational items on ‘festival and escape’

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.005 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

The most noticeable differences occurred in the motivation dimension of ‘wine’ (see Table 10.4). The mean scores varied on each of the five items included in this factor. The high involvement group showed lower level of desire than others to experience local wineries, to get familiar with local wines, and to buy wines. The high involvement group also wanted less than their low involvement counterparts to use the festival as a venue to increase their wine knowledge. The three segments differed from each other on their motivation for wine tasting, in which the low involvement group demonstrated the highest mean score and was followed by the medium involvement group.

Table 10.4 Wine involvement level and motivational items on ‘wine’

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.001 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

No differences, however, were detected in the post hoc tests upon the three items included in ‘socialization’, even though the F value was significant in the ANOVA test. Apparently the difference was minor and therefore no further information was provided in this regard. It was then deemed necessary to examine the six motivational items which were dropped in the factor analysis process. Three of the relationships were found to be significant (see Table 10.5). Compared to the high and low involvement segments, the low involvement group more likely had been to the festival before and had a good time. This may explain why they always wanted to attend the festival where they could spend some time with their friends.

Table 10.5 Wine involvement level and other motivational items

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.001 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

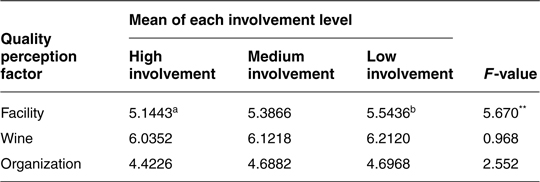

Involvement and Quality Perceptions

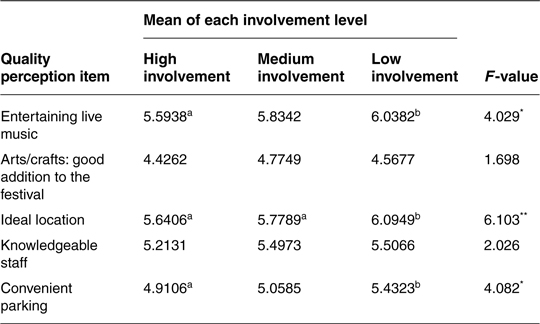

Quality perceptions encapsulated three dimensions, namely ‘facility’, ‘wine’, and ‘organization’. Only ‘facility’ showed significant mean differences in the ANOVA test (see Table 10.6). A closer look at the five ‘facility’ items found three to be different between the involvement groups. The low involvement group gave a better score than did the high involvement segment to music and parking facility. They also tended to consider the festival more ideally located than the other two groups, who had very similar opinions in this aspect (See Table 10.7). All three groups thought of ‘wine’ as exceptional, a dimension including such items as a variety of wines and multiple wineries.

Table 10.6 Wine involvement level and quality perception factors of the wine festival

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

Table 10.7 Wine involvement level and quality perception items on ‘facility’

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.005 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

Involvement and Satisfaction, Value Perception, and Behavioural Intentions

Finally, it was found that the low and medium involvement groups displayed a better perception of the festival in terms of value for money. They also would more likely return to the festival in the future. The low involvement group was also more inclined than the high involvement segment to visit local wineries after the festival (see Table 10.8). No differences were shown between the groups on overall satisfaction with the visit or the intention to buy local wines after the festival.

Finally, no significant differences were found concerning the demographic variables.

Table 10.8 Wine involvement level and satisfaction, value and behavioural intentions

* Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

** Significance at p < 0.005 level.

a,b The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level in post hoc test.

Conclusion

Wine is a beverage associated with relaxation, communicating with others, or hospitality (Bruwer, 2003). The extant literature has argued that wine consumers or wine tourists are not homogenous. In particular, wine tourists look for different types of experiences in their travel and great diversity exists among them. There is no single, stereotypical wine tourist (Mitchell and Hall, 2004). A mass-market approach therefore appears highly unrealistic. Wine tourists need to be segmented so that appropriate marketing strategies can be applied. A proper segmentation of wine tourists enables a better understanding of the characteristics and needs of the particular groups, increases the effectiveness of advertising and promotional efforts, and enables wine tourism marketers to better target customers (Dodd and Bigotte, 1997; Getz, 2000).

When examining wine consumer/tourist segmentation, researchers sometimes measure personal involvement with wine as this concept leads to a systematic analysis of consumption/travel patterns for product development and service quality evaluation. Personal involvement with wine refers to a perceived importance or relevance for and feelings of interest and enthusiasm about wine. Lockshin (1997, 2001) recommended two groups (high vs. low involvement) of wine consumers and discussed their major characteristics. Charters and Ali-Knight (2002) identified four groups of winery visitors on the basis of their interest in wine. The current study explored wine festival visitors’ segmentation using their personal involvement with wine. The findings of this study lend further support to integrate the concept of personal involvement in developing segmentation strategies aimed at high-yield wine festival visitors.

The construct was measured by a multi-item scale used in the overall consumer research realm on involvement. Visitors at a regional wine festival were clustered into three groups, those with high involvement, those with medium level involvement, and those with low involvement. Relationships to other tourist activities and behaviours at the festival were incorporated in the analysis of the segmentation of the market. Differences between the groups were subsequently found with regard to their motivations to attend the festival, their quality perceptions of the festival, their perception of the festival in terms of value for money, and their intention to visit local wineries after the festival.

The low involvement group showed constantly higher ratings on all the festival-related items included in this study. Apparently this group of visitors was less critical and attempted to enjoy the festival more as a special event. They were pleased that they did not have to travel far. The wine festival allowed an ideal venue for them, alongside their friends in a fun and relaxing setting, to do wine tasting, to come into contact with local wineries, and to increase wine knowledge, a unique experience in which their curiosity with wine could be satisfied. Therefore, they saw the festival as good value for money and would want to visit again. The experience also made them want to visit local wineries. The medium involvement group’s ratings showed similar differential patterns. The most visible difference between these two groups lied in the latter’s higher level of desire to use the festival as a venue to get away on weekend.

The low and medium involvement groups were similar to the wine novices (those with limited interest in wine) as described by Charters and Ali-Knight (2002). Their interest in wine was limited and perhaps it was not the major reason for them to attend the festival. Instead, they searched for a more diversified experience incorporating wine, food, environment, setting, learning, and cultural aspects (i.e. the appeal of a festival). It is then evident that wine festivals, if taking place at convenient locations, may attract visitors who do not intend to visit any winery or winegrowing region and thereby would never be ascribed to the category of wine tourists. This group may have limited interest in wine, but the exposure at the event had very much probably opened up the world of wine to them. Their readiness to participate in such type of festivals and their highly positive perception of the event shed light on future marketing efforts for the pursuit of new markets. The festivities put these visitors at ease and thus appealed successfully to a large group of attendees. This is where the event organizers and wine marketers may accentuate the unique ‘wine plus fun’ theme and the total wine tourism experience to help create interest in regional wines and local wineries among this group.

The high involvement group showed lower ratings on all the items. Nevertheless their high scores on certain items (X > 5.0) warrant some discussions. Apparently, the high involvement attended the wine festival because, overall speaking, they enjoy special events and more specifically they wanted to have a day out at the event. They were interested in wine tasting and an experience with local wineries without having to travel far. Besides live music and knowledge level of the staff, they also appreciated the wine variety and the large array of wineries available at the festival. They were satisfied with the visit and would like to return next year. They intended to buy local wines and to visit local wineries after the festival.

The high involvement segment seemed somewhat close to the ‘wine lovers’ group identified by Charters and Ali-Knight (2002). This was the wine-intensive group, whose members were the most highly interested in wine and saw wine as personally important to them. When attending the festival, this group could be more purpose driven, that is, to do wine tasting and experience local wineries. They were hungry for information on wine. They may have been pursuing ‘novelty’ experiences. Festival organizers and wine marketers may provide more learning opportunities (e.g. wine and food parings, seminars on healthy drinking, contests on wine tasting) for these highly involved visitors.

Ali-Knight, J. and Charters, S. (1999). The business of tourism and hospitality: The attraction and benefits of wine education to the wine tourist and Western Australian wineries. Proceedings of the Ninth Australian Tourism Hospitality and Tourism Research Conference.

Antil, J.H. (1986). Conceptualization and operationalization of involvement. Journal of Marketing Research, 22, 388–396.

Arnold, N. (1999). Marketing and development models for regional communities: A Queensland experience. Proceedings of the 9th Australian Tourism and Research Hospitality Conference, CAUTHE 1999, Adelaide, South Australia, Bureau of Tourism Research, Canberra.

Beverland, M., Hoffman, D. and Rasmussen, M. (2001). The evolution of events in the Australasian wine sector. Tourism Recreation Research, 26(2), 35–44.

Bruwer, J. (2003). South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tourism Management, 24, 423–435.

Cambourne, B. and Macionis, N. (2000). Meeting the wine-maker: Wine tourism product development in an emerging wine region. In Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B. and Macionis, N. (eds) Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets. Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 81–101.

Charters, S. and Ali-Knight, J. (2002). Who is the wine tourist? Tourism Management, 23(3), 311–319.

Collins, C. (1996). Drop in for more than just a drop. Weekend Australian, 9(March), p.3.

Derrett, R. (2004). Festivals, events and the destination. In Yeoman, I., Robertson, M., Ali-Knight, J., Drummond, S. and McMahon-Beattie, U. (eds.) Festival and Events Management: An International Arts and Culture Perspective. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 32–50.

Dodd, T. and Bigotte, V. (1997). Perceptual differences among visitor groups to wineries. Journal of Travel Research, 35(3), 46–51.

Dodd, T. and Gustafson, W. (1997). Product, environmental, and service attributes that influence consumer attitudes and purchases at wineries. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 4(3), 41–59.

Getz, D. (1997). Event Management and Event Tourism. Cognizant Communication Corporation.

Getz, D. (2000). Explore Wine Tourism: Management, Development and Destinations. Cognizant Communication Corporation.

Getz, D. and Brown, G. (2006). Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tourism Management, 27, 146–158.

Hall, C.M. (1996). Wine tourism in New Zealand. In Proceedings of Tourism Down Under II: Towards a More Sustainable Tourism. Centre for Tourism, University of Otago, Dunedin.

Hall, C.M. and Macionis, N. (1998). Wine tourism in Australia and New Zealand. In Butler, R., Hall, C.M. and Jenkins, J. (eds.) Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., pp. 197–224.

Hoffman, D., Beverland, M.B. and Rasmussen, M. (2001). The evolution of wine events in Australia and New Zealand: A proposed model. International Journal of Wine Marketing, 13(1), 54–71.

Houghton, M. (2001). The propensity of wine festival to encourage subsequent winery visitation. International Journal of Wine Marketing, 13(3), 32–41.

Jago, L., Chalip, L., Brown, G., Mules, T. and Ali, S. (2003). Building events into destination branding: Insights from experts. Event Management, 8, 3–14.

Krugman, H.E. (1965). The impact of television advertising: Learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29, 349–356.

Lockshin, L. (2001). Using involvement and brand equity to develop a wine tourism strategy. International Journal of Wine Marketing, 13(1), 72–81.

Lockshin, L., Spawton, A.L. and Macintosh, G. (1997). Using product, brand, and purchasing involvement for retail segmentation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 4(3), 171–183.

Mitchell, R. and Hall, C.M. (2004). The post-visit consumer behavior of New Zealand winery visitors. International Wine Tourism Research: Proceedings of the International Wine Tourism Conference. Margaret River, Western Australia.

Mittal, B. (1995). A comparative analysis of four scales of consumer involvement. Psychology and Marketing, 12(7), 663–682.

Salter, B. (1998). The synergy of wine, tourism and events. Wine Tourism: Perfect Partners: Proceedings of the 1st Australian Wine Tourism Conference. Margaret River, Western Australia.

Taylor, R. (2006). Wine festivals and tourism: Developing a longitudinal approach to festival evaluation. In Carlsen, J. and Charters, S. (eds.) Global Wine Tourism: Research, Management and Marketing. CAB International, Oxon, UK, pp. 175–195.

Williams, P.W. and Dossa, K.B. (2003). Non-resident wine tourist markets: Implications for British Columbia’s emerging wine tourism industry. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 14(3/4), 1–34.

Yuan, J., Cai, L.A., Morrison, A.M. and Linton, S. (2005). An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel, and special events? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(1), 37–54.

Zaichkowsky, J.L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 341–352.